We prioritise problems that are unusually large in scale, unduly neglected, and solvable, because that’s where additional people can generally have the most positive impact.

Right now problems that could pose existential risks tend to top our list, because they threaten not just those alive today but also humanity’s entire future, and they remain neglected relative to their scale. Our list is also influenced by thinking that there’s a realistic possibility of transformative AI in the coming decades.

This ranking is a best guess and a constant work in progress, meaning it’s doubtless incomplete and mistaken in many ways. It also may not align with your worldview. So we encourage you to think through the question of which problems are most pressing for yourself too. Where you focus will also depend on your opportunities to contribute to each issue.

To learn why we listed a specific problem and how you can help tackle it, click the profiles and see our FAQ below.

Our list of the most pressing world problems

Advanced AI could greatly influence the future of humanity. If this goes badly, we think it could pose an existential threat.

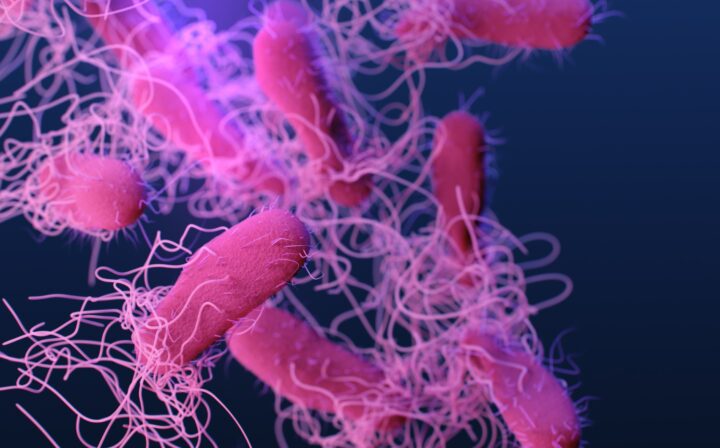

Pandemics are among the deadliest events in human history. Developments in biotechnology could make future pandemics even worse.

Nuclear weapons were the first genuine man-made existential threat. Despite some progress, the risk remains and may even increase.

There’s a significant chance of a great power war this century — and this is a major risk factor for existential catastrophes.

There are trillions of farmed animals, and the vast majority are on factory farms. The conditions in these farms are far worse than most people realise.

Rigorously investigating how to prioritise global problems and best address them can help people aiming to do good choose what to work on more effectively.

We are part of effective altruism, so we might be biased — but we think growing and improving this network of people working on solving the world’s most pressing problems is one way to do a lot of good.

The world’s most powerful institutions greatly shape humanity’s trajectory, but their decision-making is often deeply flawed. If we could find high-leverage ways to improve it, the future would be systematically brighter.

We think all these problems present many opportunities to have a big positive impact, though there’s a lot of variation in the potential of particular interventions within each area. If you want to help tackle these problems, check out our page on high-impact careers.

Emerging challenges

These problems also seem likely to be very important, but their nature is less clear and the potential solutions to them are less developed.

This means it might be a particularly impactful time to get involved — work on these problems is very neglected, so you might be able to have an outsized influence or help kick off a new field. But it also might be very hard to make meaningfully positive progress, and there are often very few available roles. In other words, your potential impact would be highly variable and uncertain.

We may soon create AI systems that are plausibly sentient or otherwise have moral status. But these issues are mired in uncertainty, and we’re not prepared to avoid the dangers.

Installing “secret loyalties” in AI systems could allow their creators to attempt an unprecedented coup.

Investment in space is increasing, but we don’t have a plan for how nations, companies, and individuals will interact fairly and peacefully there.

Could a totalitarian regime leverage progress in AI or other advanced tech to eventually gain a permanent grip on society?

The proliferation of advanced AI systems may lead to the gradual disempowerment of humanity, even if we prevent power-seeking behaviour.

If the world’s population could recover from a catastrophic collapse, the possibility of a flourishing future might remain even if a catastrophe occurs.

There is an unfathomable number of wild animals. If many of them suffer in their daily lives and if we can find a (safe) way to help them, that would do a lot of good.

Other pressing problems

We also see the following problems as very pressing, and think people should be working on them much more. We rank them here because we think that on the margin, many of our readers can do even more good focusing on the problems listed above. But this is based on values and views that are debatable, and even if they’re right, we think you can do a lot to improve lives by working on these problems too.

Preventable diseases like malaria, tuberculosis, and HIV kill millions of people each year. More funding and more effective organisations can improve health in poor countries and save a large number of lives.

Carbon emissions are raising global temperatures. Projections suggest this will result in many millions of avoidable deaths and widespread disruption and harm in the coming decades.

Spreading positive values — like (in our view) caring about the wellbeing of all sentient beings impartially — could be one of the broadest ways to help with a range of problems.

Liberal democracies seem more conducive to innovation, freedom, and possibly peace. There’s a lot of effort already going into this area, but there may be some ways to add more value.

There are many ‘public goods’ problems, where no one is incentivised to do what would be best for everyone. How can institutions and technology solve these problems better?

Some of the worst possible futures might be less likely if we better understood people who intentionally cause great harm (and stop them).

Keeping people from moving to where they would have better lives can have big negative humanitarian, intellectual, and economic effects.

Incentives shaped by universities and journals affect scientific progress. Can we improve these incentives in order to, for example, speed up the development of beneficial technologies over risky ones?

Depression, anxiety, and other conditions directly affect people’s wellbeing. Finding effective and scalable ways to improve mental health worldwide could deliver big benefits.

More problems we’ve written about

We’re less excited to see our readers work on these problems than we once were, but we’re not certain about this. If you have different empirical and philosophical beliefs, or a particularly strong fit for one of these problems, you might reasonably conclude it’s your top option.

- Whole brain emulation

- Atomically precise manufacturing

- Improving individual reasoning and cognition

- Spread of false ideas on social media

- High-leverage ways to speed up economic growth

Frequently asked questions

Our aim is to find the problems where an additional person can have the greatest social impact — given how effort is already allocated in society.

The primary way we do that is by trying to compare global problems based on their scale, neglectedness, and tractability. To learn about this framework, see our introductory article on prioritising world problems.

To assess problems based on this framework, we mainly draw upon research and advice from subject-matter experts and advisors in research communities focused on effective altruism and existential risk, including the Global Priorities Institute, Rethink Priorities, and Open Philanthropy. See more on our research processes and principles.

To see the reasons why we list each individual problem, click through to see the full profiles.

To be clear, comparing global problems is very messy and uncertain. We are far from confident that the exact ordering presented on this page is correct — in fact, we’re pretty sure that it’s incorrect in at least some ways (more on this below).

Moreover, assessments of the tractability and especially the scale of different global problems depend on your values and worldview. You can see some of the most important aspects of our worldview in our advanced series, especially our articles on how we define social impact and the weight we place on future generations.

Given our values and worldview as an organisation, we’ve found some heuristics that help guide our prioritisation:

- Emerging technologies and global catastrophic risks. New transformative technologies may promise a radically better future, but also pose catastrophic risks. We think that mitigating these risks, while increasing the chance these technologies allow future generations to flourish, may be the crucial challenge of this century. Though there is a growing movement working to address these problems, work on mitigating many risks remains remarkably neglected — in some cases receiving attention from only a handful of researchers. So you’ll see many problems dealing with technology on the lists above.

- Building capacity to research and explore problems. Comparing global problems involves lots of uncertainty and difficult judgement calls, and there have been surprisingly few serious attempts to make such big-picture comparisons, so we’re strongly in favour of work that might help resolve some of this uncertainty. This can take the form of research or trying and seeing what works in more speculative areas. The importance of information value is reflected in our recommendation of speculative areas, as well as global priorities research itself.

- Building communities to solve problems. We think it can be extremely valuable to invest in organisations and communities of people who are trying to do good as effectively as possible. We’re especially keen to build the effective altruism community, because it explicitly aims to work on whichever global challenges will be most pressing in the future. We count ourselves as part of this community because we share this aim.

We think some problems are much more pressing than others, such that by choosing carefully, an additional person can have a far greater impact.

Holding all else equal, we think that additional work on the most pressing global problems can be between 100 and 1000(!) times more valuable in expectation than additional work on many more familiar social causes like education in rich countries. That’s because in those cases, your impact is typically limited by the smaller scale of the problem (e.g. because it only affects people in one or a few countries), or because the best opportunities for improving the situation are already being taken by others. Moreover, it seems like some of the problems in the world that are biggest in scale — especially those that could affect the entire future of humanity, like mitigating risks from AI or biorisks — are also highly neglected. This combination means you can have an outsized impact by helping tackle them.

For this reason, we think our most important advice for people who want to make a big positive difference with their careers is to work on a very pressing problem. This page is meant to help readers do that. Read more about the importance of choosing the right problem.

A key consideration is how society is currently allocating resources. If a lot of people are already working on an issue, the best opportunities will have probably already been taken, which makes it harder for additional people to have an impact.

At the same time, you only have one career, so if you want to fulfil your potential to do good, you need to prioritise which issues you focus on.

One way to think about this is in terms of a ‘world portfolio’: What would the ideal allocation of resources be for all social issues? And which are farthest from that ideal allocation?

As an individual, the best you can do is pick one of these that you’re well placed to focus on.

This is why our list looks a bit surprising: we purposefully want to highlight problems that we think are furthest from getting the attention they need — such as the risk of a catastrophic engineered pandemic, which currently gets $1–2 billion of funding per year. That is only 1/500th of what a more widely recognised problem like climate change gets (which also needs more resources).

By their very nature, these issues will tend to be unusual — if working on them was common sense, they’d already have more attention, and we’d need to derank them!

Since we have only thousands of readers who will change their careers due to our advice, it’s not enough to regularly change which problems are neglected. If everyone followed our advice, however, then our list would need to be totally different (but this will never happen).

Another factor that makes our list unusual is that we strive to value the interests of all sentient beings more equally — regardless of where they live, when they live, or even what species they are.

Many people believe ‘charity begins at home,’ but we believe charity begins where you can help the most. This typically means looking for the groups who are most neglected by the current system, and this often means focusing on the world’s poorest people, animals, or future generations, rather than other citizens of the world’s richest countries.

To learn more about why we prioritise more neglected problems, see our article on comparing global problems in terms of scale, neglectedness, and solvability, and our advanced series.

Some find it objectionable to say one problem is more pressing than another — perhaps because they think it’s impossible to make such determinations, or because they think we should try to tackle everything at once.

We agree that it’s difficult to determine which problems will affect lives the most, as well as how tractable and neglected different problems are. The field of global priorities research exists because these questions are so complicated, and we are far from certain about our views (see below). But we think with careful thought and research, people can make educated guesses — and, crucially, do better than random.

We also agree that an individual can sometimes make progress on different problems at the same time, and advocating for more people or institutions to focus on helping others can increase the total amount of work done to solve all problems.

However, resources are still very much limited, and no one person can do everything at once. Given the seriousness of the many challenges humanity faces, we think we have to prioritise among problems to use our resources as effectively as we can to solve them.

Refusing to compare problems to one another doesn’t get you out of prioritising — it just means you’ll be choosing to prioritise some things over others without thinking much about it.

Definitely not. Though we’ve put a lot of work into thinking about how to prioritise global problems, ultimately we are drawing on a modest amount of research to address an unbelievably large and complex question. We are very likely to be wrong in some ways (see below). You might be able to catch some of our mistakes.

Moreover, it’s very useful for people trying to make the world a better place with their careers to develop their own views about what to prioritise — you’ll be more motivated and more able to help solve a problem if you understand the case for working on it and have chosen it for yourself.

To help you form your own views, below we suggest a rough process for creating your own list of problems.

The most important and unusual factors driving our lists are probably:

- Our focus on reducing existential risks, which we think are some of the biggest and most neglected issues in the world today.

- Our view that all future generations matter, and that some issues can affect generations stretching into the long-run future, an idea called longtermism. This further increases the importance we place on reducing existential risks and on shaping other events that could affect the long-run future.

- Our view that AI is likely to be a hugely transformative technology with effects that might last a very long time and arrive very soon. This means we especially highly prioritise reducing existential risks from AI, as well as issues that might interact with AI risks (such as bioweapons) or emerging challenges that could arise sooner due to AI.

If we were to reject longtermism, problems that contribute to existential risk would stand out less (including most of our top-recommended problems), while problems like ending factory farming, improving global health, speeding up economic growth, improving science, and migration reform would all be boosted.

That said, even if we rejected longtermism, we still think existential risks would be top problems for more people to work on! We think that risks from AI and catastrophic pandemics might arise in the next few decades — so they are also big problems for the present generation and near future generations.

You can read about some counterarguments to longtermism on our page about it.

If we didn’t think that AI would be a transformative technology any time soon, we’d focus proportionally more on biorisk and many of the other problems on our list. Read about what we think are the best objections to prioritising AI risk.

Finally, we are relatively open to working on issues where our impact is very uncertain, provided the upside seems high enough. Others have argued that it’s better to focus on issues where we can be more confident of making a positive impact, such as global health and factory farming.

Of course there are other parts of our broad worldview that could also be wrong — you can read about some of them in the articles in our advanced series.

Another major worry we have about the lists is that we’re missing an important problem because we haven’t even thought of it, but it should be ranked highly. We sometimes call this the possibility of finding a ‘Cause X.’ The possibility of finding Cause X is one reason why we rate further research and capacity-building so highly.

Previous versions of this list have already resulted in thoughtful feedback, so we’ve adjusted our views. We anticipate this list will continue to evolve, as both the circumstances of the world change and we come to understand them better.

You can see some of our key uncertainties about each individual problem by clicking through to the individual profiles, and we invite you to investigate these questions for yourself.

No. We don’t think everyone in our audience — let alone everyone in the world — should work on our top list of problems (even if everyone totally agreed with our views).

First, the pressingness of a problem is only one aspect — though a very important one — of our framework for comparing careers.

Different people will find different opportunities within each problem, and will have different degrees of personal fit for those opportunities. These other factors also really matter — you may well be able to have 100 times the impact in an opportunity that’s a better fit. That can easily make it higher impact to work on a problem you think is less pressing in general.

Moreover, as our audience expands, we need to think more in terms of a ‘portfolio’ of effort by our readers, which creates additional reasons for members to spread out (we cover this in more detail in our article on coordination). Two of the most important such reasons are:

- As more people work on a problem, it gets less neglected, and there are diminishing returns to additional work. This means that a group of people that’s large compared to the capacity for that problem to absorb people will start to run out of fruitful opportunities to make progress on it, making it better for new people to spread out into other areas.

- If you work with others, there is value of information in exploring new world problems — if you explore an area and find out that it’s promising, other people can enter it as well.

Among people who engage with our advice, we aim to help a majority shoot for one of the top world problems we list above, but our ideal would be to also help a substantial fraction of our audience work on the other problems on our list.

If we consider the world as a whole, not just our readers, it’s even more obvious that we don’t want everyone to work on our top-ranked problems. The world wouldn’t function if everyone tried to work on AI safety and preventing pandemics. Clearly, we need people working on a wide range of problems, as well as keeping society running and taking care of themselves and their families.

However, in practice it’s safe to assume that what most of the world does will remain unaffected by what we say. (If that changes, we’ll change our advice accordingly!) So we focus on finding the biggest gaps in what the world is currently doing in order to enable our readers to have as much impact as they can.

Much of our effort is allocated to creating resources that are useful no matter which problem you want to work on (such as our advice on career planning), but some resources are only relevant to a particular problem.

When it comes to these, we roughly try to allocate our efforts in line with what we think are the most pressing problems. This means we aim to spend most of our time learning, writing, and thinking about our highest-priority areas and less time on those we think are less pressing.

However, the distribution of our effort does not exactly match our views about which problems are most pressing. This is because we are a small team and there are returns to focusing and really learning about some problems, and also because we are better positioned to help people work on some problems vs others.

This means that we tend to put more effort into having great advice about the very top problems we prioritise and those for which we can have stellar advice compared to the other sources. In practice, that means we put more effort into having great advice and support in AI safety, biorisk, and building communities focused on solving pressing global problems.

We’d love to have the resources to spend substantial effort on all the problems in the lists above. But given the size of our team, we aren’t able to do much more than write an article or two on many of the topics and point readers in the direction of more informed groups.

We are so glad you’d like to help! It can seem daunting, but we’ve seen lots of people make real contributions to these problems, including people who didn’t think they could when they first came across them.

The short answer is that the individual problem profiles each have a section on how to help tackle that problem, so click through to read the full profiles.

Also, see our career reviews page and job board to get ideas for specific jobs and careers that can help.

If you want to think about what to do in more depth, see our materials on career planning.

This includes a career planning worksheet that takes you through a step-by-step process for creating your plan. In summary:

The first step is to learn more about the problems you are considering, as well as what is important to you in your career.

Then you’ll want to brainstorm longer-term career paths that will let you contribute the most — we have some ideas for these on our career reviews page. Note that each problem requires a lot of different kinds of work, from advocacy to research to helping build organisations, so you’ll have many paths to consider.

Don’t rule something out too early because it doesn’t sound at first like it’d be a fit for your skills. This is a mistake we see a lot. For example, you can help with AI safety using a variety of non-technical skills. (See some suggestions for work in governance as well as supporting roles here.)

Next, gain more information about your career options — either by talking to people, reading, or applying to jobs and trying things out — and then start narrowing them down.

It may be best to first focus on building career capital — skills, knowledge, connections, and credentials that put you in a better position to have an impact in the future.

It’s much more important to maximise the impact you can have over the course of your career than it is to have a big impact next year — which often means starting by investing in yourself.

Finally, you’ll figure out your next career step. You may still be very uncertain where to aim longer-term, but that’s OK so long as you can find a next step that puts you in a better position, e.g. by improving your career capital, or by teaching you more about where to aim longer-term, or that is impactful in itself.

We have guides to particular career paths that contain common early steps as well as pointers on how to eventually put all your experience and skill to the best use.

When you have some ideas, apply for free one-on-one career advice from our advisors, who can help you compare options and connect you with mentors and other opportunities.

The only thing you can control is contributing as well as you can — and that’s a matter not just of what the world needs, but also of your own motivation and abilities.

And balancing the two is an art.

On one hand, you might surprise yourself. We’ve worked with lots of people who weren’t immediately interested in a problem, but after they learned more and found interesting opportunities to address it, they became passionate about it over time. So don’t rule out everything you’re not immediately interested in.

But if you try to get motivated and it doesn’t work, you can try working on something else. Ultimately, finding a job that fits you is really important. It’s usually better to be doing something you’re great at rather than struggling to stay motivated working on something that’s important in the abstract. In the answer to the next question, you’ll find a few other lists of problems you can investigate besides ours.

If you really want to help with these problems but don’t feel motivated to work on them directly, you could try helping by donating to organisations that work on them. If you do this as a primary aim of your career, we call it ‘earning to give.’ You can also donate 10% of your income (or however much you’re comfortable with).

Read more about how to have a positive impact in any job.

We have an article with a process for comparing global problems for yourself. In brief, we recommend doing the following steps:

Clarify your broad worldview and values

What do you think is important? And how do you come to know the answers to that? Your answers to these questions are part of your worldview.

We discuss our worldview in our advanced series. Our article on comparing problems lists some alternative views that are common among our readers and discusses tips for figuring out which you think is more likely to be right.

Spending some time thinking about the big picture can make a big difference to where you end up focusing — just keep in mind that you’ll never have a complete and fully confident answer.

Learn more about frameworks for comparing problems

For example, we often use the importance, neglectedness, and tractability framework, in which how you assess the importance and tractability of problems is partially determined by your worldview. Also, see the article on this framework in our advanced series.

Start generating ideas

Once you have frameworks and your worldview clarified to some extent, you can start generating ideas for pressing problems, perhaps using other people’s lists to get started (like ours or others listed just below).

Compare

Now that you have your list of problems, compare them according to your worldview and using the frameworks you learned about above.

Identify key uncertainties about your list, work out what research you might do to resolve those uncertainties, then go ahead and do it, and then reassess and repeat. If some of the problems on your list overlap with ours, you can use our problem profiles as a jumping-off point for learning more.

Again, it would take a lifetime to get totally confident and make your list complete, so aim for action-relevant information instead: is further investigation likely to change what you actually work on next? If your best guesses aren’t changing, it’s probably time to stop thinking about it and focus on something else.

Moreover, you can (and should) continue to think about which problems you think are most pressing throughout your career.

Other lists of pressing global problems we’ve seen, for inspiration:

- The United Nations’ sustainable development goals

- The United Nations’ more general list of global issues

- The Global Challenges Foundation’s list of global risks

- A big list of cause candidates from the Effective Altruism Forum

Different problems need different skills and expertise, so people’s ability to contribute to solving them can vary dramatically. That said, there are also many ways to contribute to solving a single problem, so you also shouldn’t assume you can’t help with something just because you don’t have some salient qualification.

To learn more about what’s most needed to address different world problems, click through to read the profiles above.

To explore your own skills and other aspects of your personal fit (especially early in your career) and find your comparative advantage, we encourage you to make a list of career ideas, rank them, identify key uncertainties about your ranking, and then try to do low-cost tests to resolve those uncertainties. After that, we often recommend planning to explore several paths if you’re able to.

You can find more thorough guidance in our resources on career planning.

You can also look at our list of the most valuable skills you can develop and apply to a variety of problems, and how to assess your fit with each one.

If you already have experience in a particular area, see our article about how you might best be able to apply it.

Read next: The highest-impact career paths our research has identified so far

Want to find a career tackling these problems? Our list of career reviews is a good place to start.

Enter your email and we’ll mail you a book (for free).

Join our newsletter and we’ll send you a free copy of The Precipice — a book by philosopher Toby Ord about how to tackle the greatest threats facing humanity. T&Cs here.