Part 8: How to find the right career for you

Everyone says it’s important to find a job you’re good at, but no one tells you how.

The standard advice is to think about it for weeks and weeks until you “discover your talent.” To help, career advisers give you quizzes about your interests and preferences. Others recommend you go on a gap yah, reflect deeply, imagine different options, and try to figure out what truly motivates you.

But as we saw in an earlier article, becoming really good at most things takes decades of practice. So to a large degree, your abilities are built rather than “discovered.” Darwin, Lincoln, and Oprah all failed early in their careers, then went on to completely dominate their fields. Albert Einstein’s 1895 schoolmaster’s report reads, “He will never amount to anything.”

Asking “What am I good at?” needlessly narrows your options. It’s better to ask: “What could I become good at?”

That aside, the bigger problem is that these methods aren’t reliable. Plenty of research shows that while it’s possible to predict what you’ll be good at ahead of time, it’s difficult. Just “going with your gut” is particularly unreliable, and it turns out career tests don’t work very well either.

Instead, you should be prepared to think like a scientist — learn about and try out your options, looking outwards rather than inwards. Here we’ll explain why and how.

Reading time: 25 minutes

The bottom line

- Your personal fit for a job is the chance that — if you worked at it — you’d end up excelling.

- Personal fit is even more important than most people think, because it increases your impact, job satisfaction, and career capital.

- Research shows that it’s hard to work out what you’re going to be good at ahead of time. Career tests, trying to introspect, or just “going with your gut” seem like poor ways of figuring this out.

- Instead, think like a scientist: make some best guesses (hypotheses) about which careers could be a good fit, identify your key uncertainties about those guesses, then go and investigate those uncertainties.

- Look for the cheapest ways of testing your options first, creating a ‘ladder’ of tests. Usually this means starting by speaking to people already working in the job. Later it could involve applying to jobs or finding ways to do short projects that are similar to actually doing the work.

- It can take years to find your fit, and you’ll never be certain about it. So even once you take a job, see it too as an experiment. Try it for a couple of years, then update your best guesses.

- Early in your career, if you have the security, it can be worth planning to try out several career paths, aiming high, and being ready to quit if something is going so-so rather than great. You can make this easier by carefully considering which order to explore your options, and making good backup plans.

Table of Contents

- 1 Being good at your job is more important than you think

- 2 Why introspection, going with your gut, and career tests don’t work

- 3 What does work in predicting where you’ll excel, according to the research?

- 4 How can you find a job that fits? Think like a scientist.

- 5 How much should you explore in your career?

- 6 Apply this to your own career

- 7 Conclusion

- 8 Want to come back later?: Get the guide as a free book

Being good at your job is more important than you think

Everyone agrees that it’s important to find a job you’re good at. But we think it’s even more important than most people think, especially if you care about social impact.

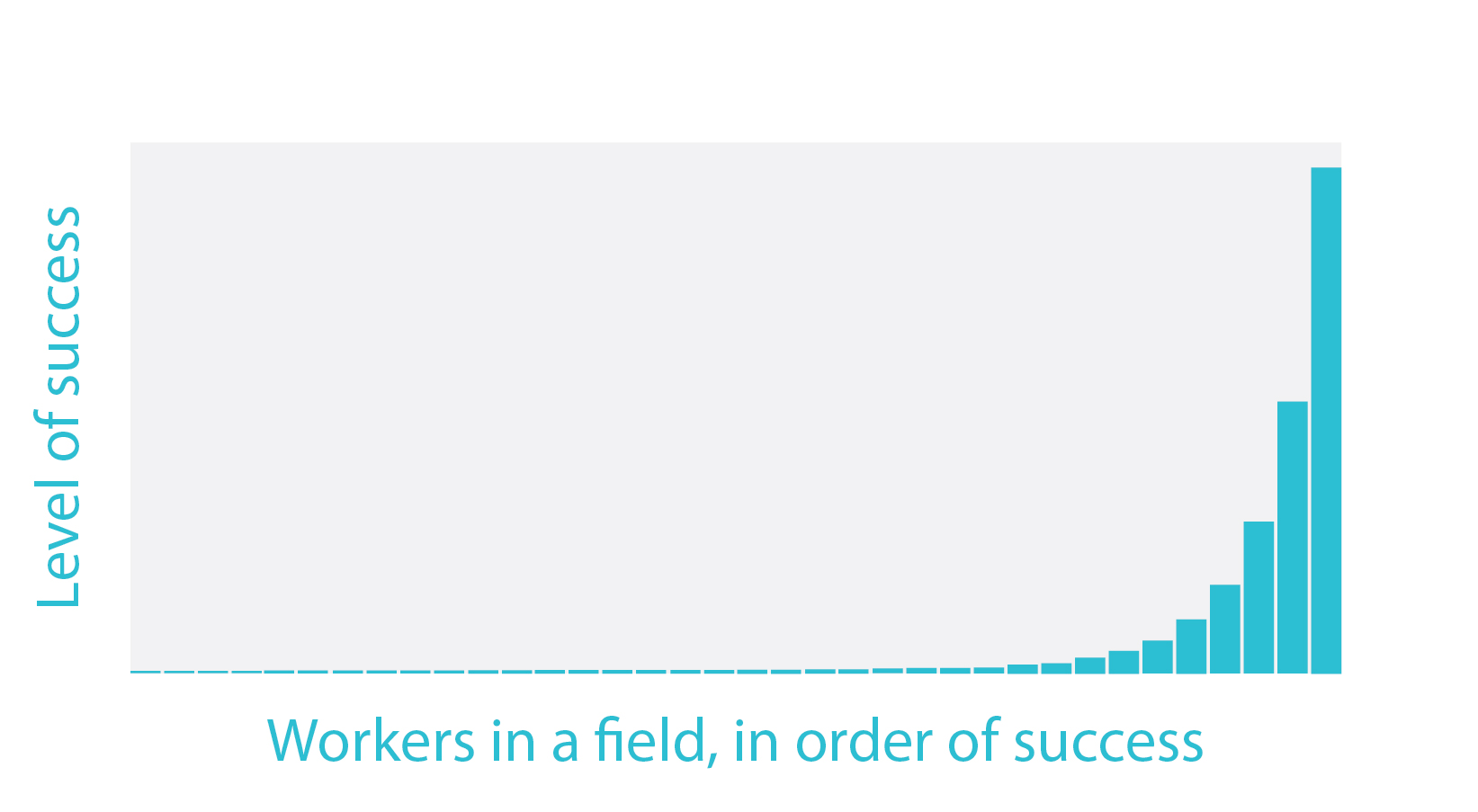

First, the most successful people in a field account for a disproportionately large fraction of the impact. A landmark study of expert performers found that:1

A small percentage of the workers in any given domain is responsible for the bulk of the work. Generally, the top 10% of the most prolific elite can be credited with around 50% of all contributions, whereas the bottom 50% of the least productive workers can claim only 15% of the total work, and the most productive contributor is usually about 100 times more prolific than the least.

So, if you were to plot degree of success on a graph, it would look like this:

It’s the same spiked shape as the graphs we’ve seen several times before in this guide.

In the article on high-impact jobs, we saw this in action with areas like research and advocacy. In research, for instance, the top 0.1% of papers receive 1,000 times more citations than the median.

These are areas where the outcomes are particularly skewed, but our review of the evidence suggests that the best people in almost any field have significantly more output than the typical person. The more complex the domain, the more significant the effect, so it’s especially noticeable in jobs like research, software engineering, and entrepreneurship.

Now, some of these differences are just due to luck: even if everyone were an equally good fit, there could still be big differences in outcomes just because some people happen to get lucky while others don’t. However, some component is almost certainly due to skill, and this means that you’ll have much more impact if you choose an area where you enjoy the work and have good personal fit.

Second, as we argued, being successful in your field gives you more career capital. This sounds obvious but can be a big deal. Generally being known as a person who gets shit done and is great at what they do can open all sorts of (often surprising) opportunities.

For example, many organisations will hire someone without experience of their area, if that person has done something impressive elsewhere (e.g. many AI companies have hired people without a background in AI). Charity and company board members are often successful people recruited from other fields. Or you might meet someone in another field who admires your work and wants to work together. (You can hear more on the case for generally kicking ass in our podcast with Holden Karnofsky.)

Moreover, being successful in any field — even if it seems a bit random — gives you influence, money, and connections, which, as we’ve also covered, can be used to promote all sorts of good causes — even those unrelated to your field.

Third, being good at your job and gaining a sense of mastery is a vital component of being satisfied in your work. We covered this in the first article.

All this is why personal fit is one of the key factors to look for in a job. We think of “personal fit” as your chances of excelling at a job, if you work at it.

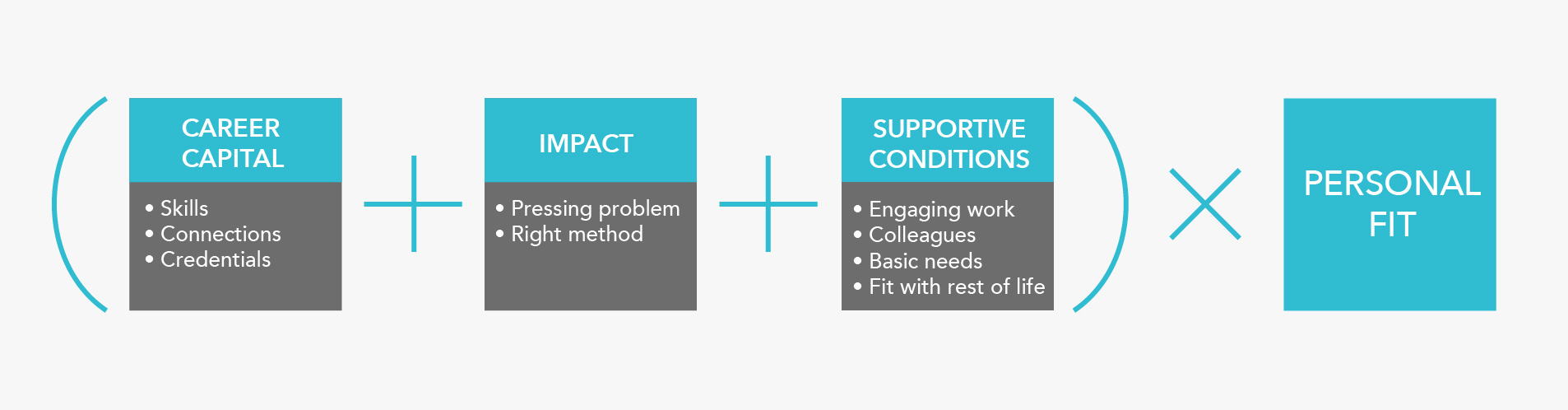

If we put together everything we’ve covered so far in the guide, this would be our formula for a perfect job:

You can use these factors to make side-by-side comparisons of different career options (learn more about how to do this in a separate article).

Personal fit is like a multiplier of everything else, which means it’s probably more important than the other three factors. So, we’d never recommend taking a “high-impact” job that you’d be bad at. But how can you figure out where you’ll have the best personal fit?

Hopefully you have some rough ideas for long-term options from earlier in the guide. Now we’ll explain how to narrow them down, and find the right career for you.

(Advanced aside: if you’re working as part of a community, then your comparative advantage compared to other people in the community is also important. Read more.)

Why introspection, going with your gut, and career tests don’t work

Performance is hard to predict ahead of time

When thinking about which career to take, our first instinct is often to turn inwards rather than outwards: “go with your gut” or “follow your heart.”

People we advise often spend days agonising over which options seem best, trying to figure it out from the armchair, or through introspection.

These approaches assume you can easily work out what you’re going to be good at ahead of time. But in fact, you can’t.

Here’s the best study we’ve been able to find so far on how to predict performance in different jobs over the next couple of years. It’s a meta-analysis of selection tests used by employers, drawing on hundreds of studies performed over 100 years.2 Here are some of the results:

| Type of selection test | Correlation with job performance (r) |

|---|---|

| IQ tests | 0.65 |

| Interviews (structured) | 0.58 |

| Interviews (unstructured) | 0.58 |

| Peer ratings | 0.49 |

| Job knowledge tests | 0.48 |

| Integrity tests | 0.46 |

| Job tryout procedure | 0.44 |

| GPA | 0.34 |

| Work sample tests | 0.33 |

| Holland-type match | 0.31 |

| Job experience (years) | 0.16 |

| Years of education | 0.10 |

| Graphology | 0.02 |

| Age | 0.00 |

Almost all of these tests are fairly bad. A correlation of 0.6 is pretty weak. And the accuracy for longer-term predictions is probably even worse.3 So even if you try to predict using the best available techniques, you’re going to be wrong much of the time: candidates that look bad will often turn out good, and vice versa.

Anyone who’s hired people before will tell you that’s exactly what happens (and there is some systematic evidence for this).4 And because hiring is so expensive, employers really want to pick the best candidates. They also know exactly what the job requires — if even they find it really hard to figure out in advance who’s going to perform best, you probably don’t have much chance.

Don’t go with your gut

If you were to try to predict performance in advance, “going with your gut” isn’t the best way to do it. Research in the science of decision-making collected over several decades shows that intuitive decision-making only works in certain circumstances.

For instance, your gut instinct can tell you very rapidly if someone is angry with you. This is because our brain is biologically wired to rapidly warn us when in danger, and to fit in socially.

Your gut can also be amazingly accurate when trained. Chessmasters have an astonishingly good intuition for the best moves, and this is because they’ve trained their intuition by playing lots of similar games, and built up a sense of what works and what doesn’t.

However, gut decision-making is poor when it comes to working out things like how fast a business will grow, who will win a football match, and what grades a student will receive. Earlier, we also saw that our intuition is poor at working out what will make us happy. This is all because our untrained gut instinct makes lots of mistakes, and in these situations it’s hard to train it to do better.

Career decision-making is more like these examples than being a chess grandmaster.

It’s hard to train our gut instinct when:

- The results of our decisions take a long time to arrive.

- We have few opportunities to practice.

- The situation keeps changing.

This is exactly the situation with career choices: we only make a couple of major career decisions in our life, it takes years to see the results, and the job market keeps changing.

Your gut can still give you clues about the best career. It can tell you things like “I don’t trust this person” or “I’m not excited by this project.” But you can’t simply “go with your gut.”

(See our evidence review for more detail.)

Why career tests also don’t work

Many career tests are built on “Holland types” or something similar. These tests classify you as one of six interest types, like “artistic” or “enterprising.” Then they recommend careers that match that type. However, we can see from the table above that “Holland-type match” is only weakly correlated with performance. It’s also only weakly correlated with job satisfaction (studies find correlations of around 0.1 to 0.3). So that’s why we don’t pay much attention to traditional career tests.

What does work in predicting where you’ll excel, according to the research?

In the table above, interviews rank near the top, which suggests the following method: talk to people who have experience recruiting in the field, and ask them how you’d stack up compared to other candidates. This makes a lot of sense — experts are probably pretty good at making this sort of judgement call.

The cluster of job tryout procedures, job knowledge tests, and work samples also do well, and that suggests another intuitive method: try to get as close to actually doing the work as possible, and then see how that goes. We talk about some ways to do that below.

Surprisingly, IQ tests correlate the most, but they’re not so useful for helping you figure out which kind of job is the best fit for you relative to other jobs (and that’s setting aside the question of what IQ tests actually measure!).

All this said, it’s important to keep in mind that none of these methods work that well. It’s just hard to say where you might be able to excel or not in the future, and this means you should keep an open mind and give yourself the benefit of the doubt — you probably have more options than it first seems!

And ultimately, the only way to find out is to take the plunge and actually try things.

How can you find a job that fits? Think like a scientist.

If it’s hard to predict where you’ll perform best ahead of time, and going with your gut intuition doesn’t work, then we need to take an empirical approach:

- Make some best guesses (hypotheses) about which options seem best.

- Identify your key uncertainties about those hypotheses.

- Go and investigate those uncertainties.

And even when your investigation is complete and you start a job, that too is another experiment. After you’ve tried the job for a couple of years, update your best guesses, and repeat.

Finding the right career for you isn’t something you’ll figure out right away — it’s a step-by-step process of coming to better and better answers over time.

Here are some more tips on each stage.

Make a big list of options

The cost of accidentally ruling out a great option too early is much greater than the cost of investigating it further, so it’s important to start broad.

And since it’s so hard to predict where you’ll excel, that also means it’s hard to rule out lots of paths!

This can also help you avoid one of the biggest decision-making biases: considering too few options. We’ve met lots of people who stumbled into paths like PhDs, medicine, or law because those options felt like the default at the time — but if they’d considered more options, they could easily have found something that fit them better.

We also meet a lot of people who think they need to stick narrowly to their recent experience. For example, they might think that because they studied biology, they should mainly look for jobs that involve biology. But what major you studied rarely matters that much.

So start by making a long list of options — longer than your first inclination. We’ll look into how to do this more in our article on planning.

Figure out your key uncertainties

You don’t have time to try or investigate every job, so you need to narrow down the field.

To start, just make some rough guesses: roughly rank your options in terms of personal fit, impact, and supportive conditions for job satisfaction (plus career capital if you’re comparing next steps rather than longer-term paths)

Then ask yourself: “What are my most important uncertainties about this ranking?”

In other words, if you could get the answers to just a few questions, which questions would tell you the most about which option should be top?

People often find the most important questions are pretty simple things, like:

- If I applied to this job, would I get in?

- Would I enjoy this aspect of the job?

- Would the pay be high enough given my student loans?

- What’s the day-to-day routine actually like?

- Does this job fit with my personal priorities (such as family commitments and having children)?

We have some more tips on how to predict your fit below.

Do cheap tests first

Now that you have a list of uncertainties, try to resolve them!

Start with the easiest and quickest ways to gain information first.

We often find people who want to, say, try out economics, so they apply for a master’s programme. But that’s a huge investment. Instead, think about how you can learn more with the least possible effort: “cheap tests.”

In particular, consider how you might be able to eliminate your top option. Or consider what you might need to find out to move a different option to the top slot.

When investigating a specific option, you can think of creating a ‘ladder’ of tests.

After each step, reevaluate whether the option still seems promising, or if you can skip the remaining steps and move on to investigate another option.

One such ladder might look like this:

- Read our relevant career reviews, all our research on a given topic, and do some Google searches to learn the basics. (1–2 hours)

- Speak to someone in the area. (2 hours)

- Speak to three more people who work in the area and read one or two books. (20 hours)

- Consider using some of the additional approaches to predicting success below.

- Given your findings in the previous steps, look for a relevant project that might take 1–4 weeks of work — like applying to jobs, volunteering in a related role, or doing a side project in the area — to see what it’s like and how you perform.

- Only then consider taking on a 2- to 24-month commitment — like a work placement, internship, or graduate study. Being offered a trial position with an organisation for a couple of months can be ideal, because both you and the organisation want to quickly assess your fit.

If you’re choosing which restaurant to eat at, the stakes aren’t high enough to warrant much research. But a career decision will influence decades of your life, so it could easily be worth weeks or months of work making sure you get it right.

Try something (and iterate)

You’ll never be certain about which option is best, and even worse, you may never even feel confident in your best guess.

So when should you stop your research and try something?

Here’s a simple answer: when your best guess stops changing.

If you keep investigating, but your answers aren’t changing, then the chances are you’ve hit diminishing returns, and you should just try something.

Of course, some decisions are harder to reverse or higher stakes than others (e.g. going to medical school). So all else equal, the bigger the decision, the more time you should spend investigating, and the more stable you want your answers to be.

Once you take the plunge and start a job, it helps to remember that even this is just an experiment. In most cases, if you try something for a couple of years and it doesn’t work out, you can try something else.

With each step you take, you’ll learn more about what fits you best.

See our individual career reviews for more advice on how to assess your fit with a specific job, including once you’re already in the path.

Advanced: what are the best ways to predict career fit, according to the research?

Our key advice on predicting fit is to define your key uncertainties and go investigate them in whatever way seems most helpful.

But it’s also true that, based on the research and our experience, some approaches to predicting fit seem better than others.

You can use these prompts to better target your efforts to gain information, and to make better guesses before you start doing lots of investigation.

- What is the job actually like? We often meet people who speculate on their fit for, say, working in government, but have little idea what civil servants actually do. Before you go any further, try to get the basics down: Can you describe what a typical day might look like? What tasks create value in the job? What does it take to do them well?

- What do experts say? If you can, ask people experienced in the field about how well you’d perform — especially people with experience recruiting for the job in question. But be careful — don’t put too much weight on a single person’s view! And try to find people who are likely to be honest with you.

- What’s been working for you so far?5 One simple method to predict your success is to project forward your track record. If you’ve been succeeding in a path, that’s normally a good reason to continue. You can also try to use your track record to make more precise estimates of your chances. For instance, if you’re at grad school, roughly the top half of your class will go into academia, so if you’re in the top 25% of your class at grad school, you could roughly guess you’ll be in the top 50% of academia.6 To get a better sense of your potential over the long term, you should try to look at your rate of improvement rather than just recent performance.7

- What drives success in the area, and how do you stack up? Your answers to steps 1–3 give you a starting point, but then you can modify that up or down depending on specific factors that could increase or decrease your chances of success. The aim is to develop a model of what’s needed for success. You can try to do this by asking people in the field about what’s most needed, and trying to understand what causes people to succeed or not. Then try to assess how you stack up on these predictors. This is how (good) job interviews work: they try to identify the traits most important for the job, and then ask you about evidence that you’ve displayed those traits in the past.

- Does the job match your strengths? One useful way to find your strengths is to look for activities that don’t feel like work to you, but do for most people. We have an article with an evidence-driven process to assess your personal strengths.

- Do you feel excited about it? Gut-level motivation isn’t a reliable predictor of success. But if you don’t feel motivated, you probably won’t be able to put in the effort you’d need to to perform well. So a lack of excitement should definitely give you pause; it might be worth exploring what precisely you find uninspiring.

- Will you enjoy it? This matters even if you mainly care about social impact: to stick with any career for long enough to make a difference, it’ll need to be reasonably enjoyable and fit with the rest of your life. For example, if you want to have children, you’ll probably want a job without extreme working hours.

- Combine all these perspectives. Predicting career success is hard, and there’s no single approach that’s reliable. So it’s useful to consider all of the perspectives above, and focus on options that seem good from several of them.

See our individual career reviews for more advice on how to assess your fit with a specific job.

Making good predictions in general is difficult. But it’s also very useful if your aim is to do good, so we also have an article on how to get better at making decisions and predicting the future.

How much should you explore in your career?

Suppose you’ve decided to try a job for a few years. You now face a tradeoff: should you stick with it, or quit with the hope of finding something better?

Many successful people explored a lot early in their career. Tony Blair worked as a rock music promoter before going into politics. Maya Angelou worked as a cable car conductor, a cook, and a calypso dancer before she switched into writing and activism, while Steve Jobs even spent a year in India on acid, and considered moving to Japan to become a zen monk. That’s some serious exploration.

Examples of people who specialised early, like Tiger Woods, often stand out to us — but it doesn’t seem necessary to specialise that early, and it’s probably not even the norm. In the book Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World, David Epstein argues that most people try several paths, and that athletes who try several sports before settling on one tend to be more successful — holding up Roger Federer as a foil to Tiger.

A 2018 study in Nature found that “hot streaks” among creatives and scientists tended to follow periods of exploring several areas.

And today, it’s widely accepted that many people will work in several sectors and roles across their lifetime. The typical 25- to 34-year-old changes jobs every three years,8 and changes are not uncommon later too.

And if personal fit is as important as we’ve argued, it could be worth spending many years finding the job that’s best for you.

But of course, exploring is also costly. Changing career paths can take years, and if you do it too often it can look flaky. Also, some paths can be hard to reenter once you’ve left them.

Steve Jobs liked to say you should “never settle.” But that’s not realistic advice. The real question is how to balance the costs of exploration with the benefits.

Fortunately, there’s been plenty of research in decision science, computer science, and psychology about this question. For instance, we interviewed Brian Christian, author of Algorithms to Live By: The Computer Science of Human Decisions about how to summarise this research, and we have an advanced series article all about it.

These are some of the key findings.

Explore more when you’re young

Everyone agrees that the earlier you are in your career, the more exploratory you should be.

This is because the earlier you discover a better option, the longer you have to take advantage of it.

If you discover a great new career at age 66 and retire at age 67, you’ve only benefited for one year. But if you discover something new at age 25, you may have decades to enjoy it.

In addition, early on you know relatively little about your strengths and options, so you learn a lot more from trying things.

Society is also structured to make it easier for younger people to explore — for instance, many internships are only available to people who are still at college — so the costs of trying other paths are also lower when younger.

Consider trying several paths (with careful ordering)

One exploration strategy is to try several paths, and then commit to whichever seems best at the end. (This is similar to the solution to the (anachronistically named) “secretary problem” in computer science, which is about how long to spend searching for the best candidate to hire from a pool of applicants.)

This strategy is most suitable while an undergraduate or in your first couple of jobs, when exploration is easiest and most valuable, and when your uncertainties are greatest.

The main downside of this strategy is that it’s costly to try out several paths. However, it’s often possible to reduce the costs significantly by carefully ordering your options. For example, you can try out a surprising number of paths between undergraduate and graduate school, during summer breaks, or by putting more reversible options first.

Here’s some more detail on how to order your next steps:

1. Explore before graduate school rather than after (and put other reversible options first)

In the couple of years right after you graduate, you’re not expected to have your career figured out right away — generally, you have licence to try out something more unusual, like starting a business, living abroad, or working at a nonprofit.

If it doesn’t go well, you can use the “graduate school reset”: do a master’s, MBA, law degree, or PhD, which lets you return to a standard path.

We see lots of people rushing into graduate school or other conventional options right after they graduate, which makes them miss one of their best opportunities to explore.

It’s especially worth exploring before a PhD rather than after. At the end of a PhD it’s hard to leave academia. This is because going from a PhD to a postdoc, and then into a permanent academic position — you’re unlikely to succeed if you don’t focus 100% on research. So, if you’re unsure about academia, try out alternatives before your PhD if possible.

Similarly, it’s easier to go from a position in business to a nonprofit job than vice versa, so if you’re unsure between the two, take the business position first.

2. Choose options that let you experiment

An alternative approach is to take a job that lets you try out several areas by:

- Letting you work in a variety of industries. Freelance and consulting positions are especially good for this.

- Letting you practice many different skills. Jobs in small companies are often especially good on this front.

- Giving you the free time and energy to explore other things outside of work.

3. Try something on the side

If you’re already in a job, think of ways to try out a new option on the side. Could you do a short but relevant project in your spare time, or in your existing job?

If you’re a student, try to do as many internships and summer projects as possible. Your university holidays are one of the best opportunities in your life to explore.

4. Consider including a wildcard

One drawback of the strategies above is that your best path might well be something you haven’t even thought of yet.

This is why in computer science, many exploration algorithms have a random element — making a random move can help avoid settling into a ‘local optimum.’ While we wouldn’t recommend literally picking randomly, the fact that even computer algorithms find randomness helpful illustrates the value of trying something very different.

That could mean trying something totally outside your normal experience, like living in a very different culture, participating in different communities, or trying different sectors from the ones you already know (e.g. nonprofits, government, corporate).

For instance, I (Benjamin) went to learn Chinese in China before I went to university. I didn’t have any specific ideas about how it would be useful, but I felt I learned a lot from the experience, and it turned out to be useful when I later worked to create our resources for people working on China-Western coordination around emerging technologies.

Jess – a case study in exploring

Here’s a real-life example: when Jess graduated from maths and philosophy, she was interested in academia and leaned towards studying philosophy of mind, but was concerned that it would have little impact.

“80,000 Hours has nothing short of revolutionised the way I think about my career.”

So the year after she graduated, she spent several months working in finance. She didn’t think she’d enjoy it, and she turned out to be right, so she felt confident eliminating that option. She also spent several months working in nonprofits, and reading about different research areas.

Most importantly, she spoke to loads of people, especially in the areas of academia she was most interested in. This eventually led to her being offered to study a PhD in psychology, with a focus on how to improve decision-making by policymakers.

During her PhD, she did an internship at a think tank that specialised in evidence-based policy, and started writing about psychology for an online newspaper. This allowed her to explore the ‘public intellectual’ side of being an academic, and the option of going into policy.

At the end of her PhD, she could have either continued in academia, or switched into policy or writing. She also could have gone back to finance or the nonprofit sector. Most importantly, she had a far better idea of which options were best.

A rational reason to shoot for the stars

Young people are often advised to “dream big,” “be more ambitious,” or “shoot for the stars” — is that good advice?

Not always. When asked, more than 75% of Division I basketball players thought they would play professionally, but only 2% actually made it. Whether or not the players in the survey were making a good bet, they overestimated their chances of success… by over 37 times.

Telling people to aim high doesn’t make sense when people are so overconfident in their chances of success.

But when you’re more calibrated, it often is good advice.

Suppose you’re comparing two options:

- Earning to give as a software engineer

- Research in AI safety

Imagine you think your chances of success in research aren’t very high, so most likely you’ll have more impact earning to give. But, if you do succeed in research, it would be much higher impact.

If you only get one shot to choose, you should earn to give.

But the real world isn’t normally like that. If you try the research path, and it doesn’t work out, you can most likely go back to earning to give. But if it does work out, then you’ll be in a much higher-impact path for the rest of your career.

That is, there’s an asymmetry. This means that if you can tolerate the risk, it’s better to try research first.

More generally, you stand to learn the most from trying paths that:

- Might be really, really good…

- But that you’re very uncertain about.

In other words, long shots.

In this sense, the advice to shoot for the stars makes sense, especially for young people.

An aggressive version of this strategy is to rank your options in terms of upside — that is, how good they would be if they go unusually well (say in the top 10% of scenarios) — then start with the top-ranked one. If you find you’re not on track to hit the upside scenario within a given time frame, try the next one, and so on.

This is usually only suitable if you have good backup options and the fortunate position of being able to try lots of things.

A more moderate version of this strategy is to use it as a tiebreaker: when uncertain between two options, pick the one with the bigger potential upside.

(Also see our advanced series article on when to be more ambitious.)

If unsure, quit

The sunk cost bias is the tendency to keep doing something that doesn’t make sense anymore, just because of how much you’ve already paid for it. It leads us to expect people to:

- Continue with their current path for too long.

- Want to avoid the short-term costs of switching.

- Be averse to leaping into an unknown new option.

This all suggests that if you’re on the fence about quitting your job, you should quit.

This is exactly what an influential randomised study found. Steven Levitt recruited tens of thousands of participants who were deeply unsure about whether to make a big change in their life. After offering some advice on how to make hard choices, those who remained truly undecided were given the chance to flip a coin to settle the issue — 22,500 did so.

Levitt followed up with these participants two and six months later to ask whether they had actually made the change, and how happy they were on a scale of 1 to 10. It turned out that people who made a change on an important question gained 2.2 points of happiness out of 10!

Of course, this is just one study, and we wouldn’t be surprised if the effect were smaller on replication. But it lines up with what we’d expect.

Apply this to your own career

In the earlier articles, you should have made a list of some ideas for longer-term career paths to aim towards.

Now you could start to narrow them down.

- Make a rough guess at which longer-term paths are most promising on the balance of: impact, personal fit, and job satisfaction.

- What are some of your key uncertainties about this ranking? List out at least five.

- How might you be able to resolve those key uncertainties as easily as possible? Go and investigate them. Consider doing one or two cheap tests.

- Which option do you think has the most upside potential?

- If you were going to try out several longer-term paths, what would be the ideal way to order those tests?

- How confident do you feel in your longer-term options? Do you think you should (i) do more research into comparing your longer-term options? (ii) try to enter one (but with a backup plan)? (iii) plan to try out several longer-term paths? or (iv) just gain transferable career capital and figure out your longer-term paths later?

If you want to think more about your longer-term options, try our full process for comparing a list of career options:

Conclusion

We like to imagine we can work out what we’re good at through reflection, in a flash of insight. But that’s not how it works.

Rather, it’s more like a scientist testing a hypothesis. You have ideas about what you can become good at (hypotheses), which you can test out (research and experiments). Think you could be good at writing? Then start blogging. Think you’d hate consulting? At least speak to a consultant.

If you don’t already know your “calling” or your “passion,” that’s normal. It’s too hard to predict which career is right for you when you’re starting out, and even sometimes when you’re many years in.

Instead, go and try things. You’ll learn as you go, heading step by step towards a fulfilling career.

Once you’ve chosen an area, how can you ensure you succeed? That’s what we cover in the next article. After that, we’ll show how to fit everything together into a career plan.

Read next: Part 9: Evidence-based advice on how to succeed in any job

Or see an overview of the whole career guide.

Notes and references

- Simonton, Dean K. “Age and outstanding achievement: What do we know after a century of research?” Psychological bulletin 104.2 (1988): 251. PDF↩

- Schmidt, Frank L., and John E. Hunter. “The validity and utility of selection methods in personnel psychology: Practical and theoretical implications of 100 years of research findings.” Working paper (2016). PDF↩

- We’re pretty confident this is true, because uncertainty compounds over time.

For example, Ericsson has argued that the best predictor of expert performance over longer time frames is how much ‘deliberate practice’ someone has done.

But a 2014 meta-analysis found that this only explained about 20% of the variance, and that was in fields like sport, chess, and music, where deliberate practice is comparatively more important. In the other professions, it was only 1%.

This suggests that even the best predictor we have doesn’t tell us that much.↩

Career choices, for instance, are often abandoned or regretted. An American Bar Association survey found that 44% of lawyers would recommend that a young person not pursue a career in law. A study of 20,000 executive searches found that 40% of senior-level hires “are pushed out, fail or quit within 18 months.” More than half of teachers quit their jobs within four years.

- If the outcome of a choice of career path is dominated by ‘tail’ scenarios (unusually good or bad outcomes), which we think it often is, then you can approximate the expected impact of a path by looking at the probability of the tail scenarios happening and how good/bad they are.↩

- If we suppose that the 50% with the best fit continue to academia, then you’d be in the top half. In reality, your prospects would be a little worse than this, since some of your past performance might be due to luck or other factors that don’t project forward. Likewise, past failures might also have been due to luck or other factors that don’t project forward, so your prospects are a bit better than they’d naively suggest. In other words, past performance doesn’t perfectly predict future performance.↩

- More technically, you can try to make a base rate forecast.↩

Median employee tenure was generally higher among older workers than younger ones. For example, the median tenure of workers ages 55 to 64 (9.8 years) was more than three times that of workers ages 25 to 34 years (2.8 years). Also, a larger proportion of older workers than younger workers had 10 years or more of tenure. For example, among workers ages 60 to 64, 53 percent had been employed for at least 10 years with their current employer in January 2022, compared with 9 percent of those ages 30 to 34.

Archived link, retrieved 06-Mar-2023.↩