Will high stress kill you, save your life, or neither?

Many people assume stress is obviously bad, and lots of people tell us they want to find a “low stress job”. But a new book (and TED talk with over 10 million views) by psychologist Kelly McGonigal claims that stress is only bad if you think it is, and that stress can make us stronger, smarter and happier. So are most people wrong, or is stress only bad if you have the wrong attitude towards it?

We did a survey of the literature, and found that as is often the case, the truth lies in between. Stress can be good in some circumstances, but some of McGonigal’s claims also seem overblown.

In summary, whether work demands have good or bad effects seems to depend on the following things:

| Variable | Good (or neutral) | Bad | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of stress | Intensity of demands | Challenging but achievable | Mismatched with ability (either too high or too low) |

| Duration | Short-term | On-going | |

| Context | Control | High control and autonomy | Low control and autonomy |

| Power | High power | Low power | |

| Social Support | Good social support | Social isolation | |

| How to cope | Mindset | Reframe demands as opportunities, stress as useful | View demands as threats, stress as harmful to health |

| Altruism | Performing altruistic acts | Focusing on yourself | |

Source for social support.1 Source for altruism.2

Our main conclusions are:

- The consensus among researchers seems to be that stress is good when it’s moderate in intensity (not too low or too high) and when it’s short-term, rather than on-going.

- Intense and on-going stress is strongly linked to poor health, including a weakened immune system, heart disease, depression and anxiety disorders, and higher chance of death.

- Some studies have found a correlation between negative health outcomes and believing that stress is bad for your health, but it is hard to draw causal conclusions from these findings. However, there is experimental evidence that reframing stress as an opportunity rather than as a threat leads to better performance and better cardiovascular health at least in the short term.

- Some studies suggest that people in higher responsibility positions, with greater job demands, have better health outcomes and are less stressed than people in lower responsibility positions. This may be because those in higher responsibility positions also tend to have greater autonomy, control and power.

Table of Contents

- 1 Research process

- 2 How is stress usually defined by scientists?

- 3 What is work related stress?

- 4 What’s the evidence stress is bad? Why do people think it is?

- 5 What are some puzzles in the literature that suggest this simple picture is wrong?

- 6 What’s the evidence that some types of ‘stress’ are good?

- 7 Under what circumstances is ‘stress’, that is, high demands, good or bad?

- 8 How can stress best be managed?

- 9 Sources surveyed

Research process

We surveyed the literature to find out how stress is usually defined, the causes of work stress, the evidence for its positive and negative effects and what the most effective stress management interventions are. See the sources at the end of this post.

How is stress usually defined by scientists?

From Stress and Health: Psychological, Behavioral, and Biological Determinants (all emphases ours):

“A widely used definition of stressful situations is one in which the demands of the situation threaten to exceed the resources of the individual.”

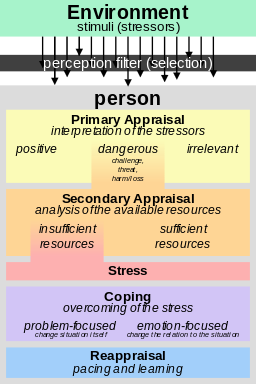

The Transactional Model of Stress and Coping, emphases the role of subjective perception in stress:

“Stress can be thought of… as occurring when “pressure exceeds one’s perceived ability to cope.”

What is work related stress?

From the World Health Organisation:

“Work-related stress is the response people may have when presented with work demands and pressures that are not matched to their knowledge and abilities and which challenge their ability to cope.”

What’s the evidence stress is bad? Why do people think it is?

Intense and on-going stress is strongly linked to poor health, including a weakened immune system, heart disease, depression and anxiety disorders, and higher chance of death.

One review of the scientific literature on the effects of stress finds that intense and prolonged stress is linked to negative health outcomes —Stress and Health: Psychological, Behavioral, and Biological Determinants (emphasis ours):

“… if stressors are too strong and too persistent in individuals who are biologically vulnerable because of age, genetic, or constitutional factors, stressors may lead to disease. This is particularly the case if the person has few psychosocial resources and poor coping skills.”

This is quite a mature field of research, which includes controlled studies, animal studies, and many proposed causal models. For example:

“… in a more controlled study, people were exposed to a rhinovirus and then quarantined to control for exposure to other viruses (Cohen et al. 1991). Those individuals with the most stressful life events and highest levels of perceived stress and negative affect had the greatest probability of developing cold symptoms.”

Another review concludes the same thing — RAND – Stress and Performance: A Review of the Literature and Its Applicability to the Military:

“However, while exposure to some level of stressor may help individual performance, the long-term effects of stress on the individual tend to be negative, according to the majority of research looking at prolonged exposure to stress.”

It also cites evidence (Table 3.1) that some stressors lead to worse job performance, and that long-term exposure to stress leads to emotional exhaustion and burnout.

The US National Institute of Mental Health fact sheet on stress claims that chronic stress may lead to various health problems:

“People under chronic stress are prone to more frequent and severe viral infections, such as the flu or common cold, and vaccines, such as the flu shot, are less effective for them.”

“Over time, continued strain on your body from routine stress may lead to serious health problems, such as heart disease, high blood pressure, diabetes, depression, anxiety disorder, and other illnesses.”

The same is stated by the American Psychological Association (emphases ours):

“Chronic stress can affect both our physical and psychological well-being by causing a variety of problems including anxiety, insomnia, muscle pain, high blood pressure and a weakened immune system. Research shows that stress can contribute to the development of major illnesses, such as heart disease, depression and obesity.”

A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies on the association between stress and risk of stroke concluded that:

“Current evidence indicates that perceived psychosocial stress is independently associated with increased risk of stroke.”

Finally, looking specifically at work related stress, an overview of systematic reviews (which is above even a systematic review in the evidence hierarchy), focused on the question of whether work related stress leads to higher cardiovascular morbidity and mortality concluded that:

“This OSRev [Overview of Systematic Reviews] confirmed that work-related stress is an important social determinant of CV [Cardiovascular] diseases and mortality.”

What are some puzzles in the literature that suggest this simple picture is wrong?

Some studies suggest that people in higher responsibility positions, with greater job demands, have better health outcomes and are less stressed than people in lower responsibility positions. This may be because those in higher responsibility positions also tend to have greater autonomy, control and power.

One puzzle is that people with higher responsibility jobs, which you’d expect to be more stressful, have been found to have better health outcomes than those with lower responsibility jobs.

From Why you should stop sweating everyday aggravations and embrace the benefits of stress (emphases ours):

“In a series of classic studies in Britain, dubbed the Whitehall studies for the road in London where the government resides, researchers examined nearly 30,000 employees in the British civil service. All had secure jobs, livable wages and access to the same health care; they also worked within a precise hierarchy, with six levels of ranks. The researchers found that heart disease and mortality rates increased steeply with every step down the ladder. Those on the lower rungs tended to lead less healthy lives—they smoked more, for example—but even factoring in lifestyle differences, the lowest-ranking employees had twice the mortality rate of the highest-ranking individuals. The researchers attributed this disparity to the psychological stresses of low status and lack of control.”

The Whitehall studies did find that higher rank was correlated with higher job demands (0.32 in men and 0.40 in women), but it was also correlated with higher control over skill use, time allocation and organisational decisions (0.51 in men and 0.55 in women). Overall, the studies actually found that higher job demands3 (and low control to a lesser extent) were associated with higher risk of heart disease and mortality:

“People with high demands, and to a lesser extent, low control, are at increased risk for heart disease.”

It seems the negative effects of higher job demands in higher ranks were offset by the higher sense of control, but overall, higher job demands were still associated with higher risk of heart disease.

Another study found a similar result. From Why you should stop sweating everyday aggravations and embrace the benefits of stress (emphases ours):

“High-ranking individuals may have demanding jobs, but they also enjoy a greater sense of autonomy. In a study that appeared in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences just before the 2012 presidential election, researchers found that a group of leaders—military officers and government officials—had lower resting cortisol and self-reported anxiety than a comparable group of nonleaders. This is despite the fact that leaders appeared more taxed: They slept significantly fewer hours per night than nonleaders. Among the leaders, those who managed more people and had more authority also had lower cortisol levels and lower anxiety than those with less clout, and this association was directly related to their greater sense of control.”

However, as the authors of this study themselves note, it could be that leaders had a predisposition to low stress levels and that’s what caused them to get into leadership positions in the first place (emphasis ours):

“It is important to note that the low stress levels of leaders may both cause and result from leadership. That is, individuals with low stress levels may be particularly well-suited for leadership and as a result, may select into leadership positions. Conversely, leadership roles may confer lower stress because of the psychological resources that they afford.”

Also, the authors argue that leadership positions are actually associated with lower levels of stress: “… we found clear evidence that leadership is associated with lower levels of stress”. Therefore this study isn’t a finding that stress is linked to positive health outcomes, instead it’s pointing out that leadership positions are associated with lower stress than other positions.

The authors’ favored explanation for this finding is that the higher demands of leaders are offset by higher levels of control – having a large number of subordinates that you have authority over – making it the case that leaders experience less stress than non-leaders:

“Leaders possess a particular psychological resource—a sense of control—that may buffer against stress.”

In sum, these studies suggest that the increased control and power that comes with higher responsibility positions offsets the negative effects of higher job demands.

Another interesting finding is that there is an association between the negative health effects of stress and believing that stress has negative health effects. Some studies have found a correlation between negative health outcomes and believing that stress is bad for your health, but it is hard to draw causal conclusions from these findings. However, there is experimental evidence that reframing stress as an opportunity rather than as a threat leads to better performance and better cardiovascular health at least in the short term.

From Why you should stop sweating everyday aggravations and embrace the benefits of stress (emphases ours):

“In the early 1990s, researchers surveyed 7,268 participants from one of the Whitehall cohorts about their current stress levels and their perceptions of the impact of stress on their health. Independent of job rank, initial health status or the level of stress reported, those who believed that stress had a large effect on their health had double the risk of suffering a heart attack within the 18-year follow-up period compared with those who viewed stress as being unrelated to their health. Similarly, in a large U.S. study, people with high stress levels had an elevated mortality rate only if they also believed that stress greatly affects health.”

However, psychologist Robert Epstein points out that this correlation can also be explained in another way:

“There is a simpler, less mysterious way of accounting for the results: people who experience stress but who suffer minimal ill effects from it come to believe that stress cannot hurt them, whereas people who do suffer ill effects come to believe that stress is harmful. Voilà, we now have the correlation those researchers found but with belief as an outcome rather than a cause.”

This is indeed what the authors of the large US study themselves say:

“In addition, reverse causality may partially explain the findings in this study. Adults who reported poor health may have been more likely to report that stress impacts their health simply due to their poor health status; moreover poor health status could also have influenced the amount of stress reported. The cross-sectional nature of these data precludes us from examining the direction of causality among the amount of stress, the perception that stress affects health, and health outcomes.”

However, there is some evidence that changing how people view stress can, at least in the short term, affect their physiological responses. From Why you should stop sweating everyday aggravations and embrace the benefits of stress (emphases ours):

“Additionally, how people view stress—as a threat versus an opportunity—can alter their physiologic responses to it. In a 2011 study at Harvard, volunteers were exposed to positive messages about stress—that it’s adaptive and aids performance—prior to a public speaking task. They had healthier cardiovascular profiles (their hearts pumped more efficiently and their blood vessels constricted less) during the stressor than controls who were given no information or were told to suppress stressful emotions. “This shows that you can change your moment-to-moment cardiovascular physiology depending on how you think about stress,” McGonigal says.”

This fits well with the large amount of evidence for the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy, whose slogan is that changing your beliefs about a situation changes the emotions you feel.

However, psychologist Robert Epstein warns against taking this positive view of stress too far:

“Although this strategy might work for some, there are still thousands of studies showing the ill effects of stress on the immune system, mood, the brain, sleep, sexual functioning, you name it. If some people feel and function better when we tell them stress is good, I’m all for it. But stress is still a killer.”

What’s the evidence that some types of ‘stress’ are good?

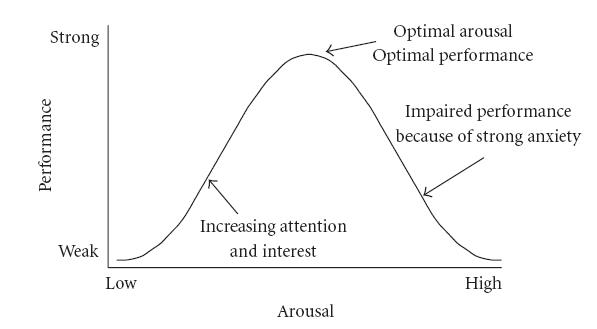

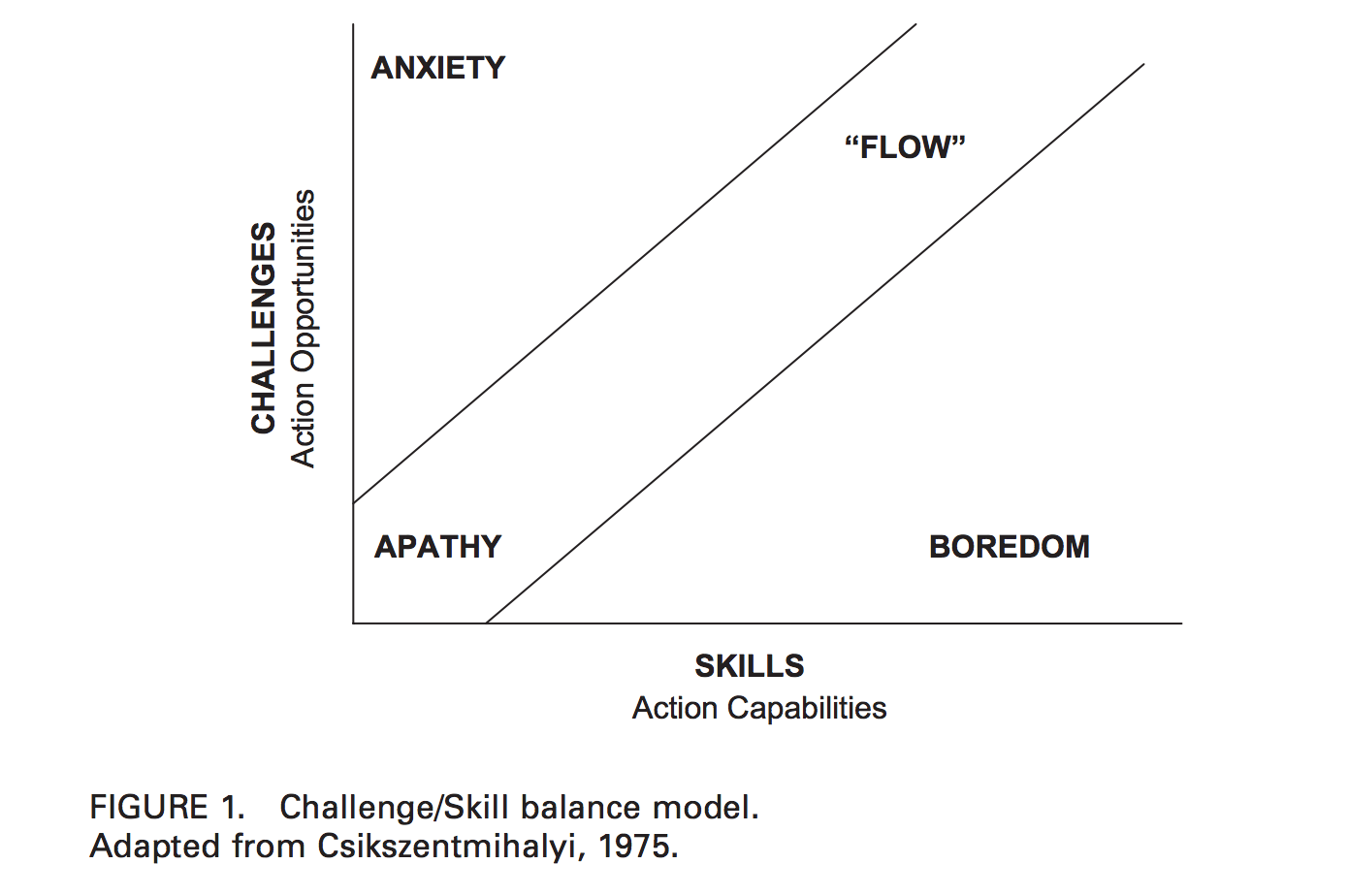

The consensus among researchers seems to be that stress is good when it’s moderate in intensity (not too low or too high) and when it’s acute, rather than chronic. Moderate and short-term stress at work is linked with better performance and higher job satisfaction.

The American Psychological Association sees the view that stress is always bad for you as a common myth:

Myth 2: Stress is always bad for you.

“According to this view, zero stress makes us happy and healthy. Wrong. “Stress is to the human condition what tension is to the violin string: too little and the music is dull and raspy”; too much and the music is shrill or the string snaps. Stress can be the kiss of death or the spice of life. The issue, really, is how to manage it. “Managed stress makes us productive and happy”; mismanaged stress hurts and even kills us.”

From Stress and Health: Psychological, Behavioral, and Biological Determinants (emphases ours):

“Acute stress responses in young, healthy individuals may be adaptive and typically do not impose a health burden. Indeed, individuals who are optimistic and have good coping responses may benefit from such experiences and do well dealing with chronic stressors (Garmezy 1991, Glanz & Johnson 1999).”

RAND – Stress and Performance: A Review of the Literature and Its Applicability to the Military (emphasis ours):

“Research also suggests that moderate levels of stress can have positive effects on job satisfaction and organizational commitment while reducing turnover intent. These findings seem to be an extension of the inverted-U-shaped relationship discussed previously. Under this hypothesis, at moderate levels of stress, individual performance and productivity are likely to be higher and can also contribute to higher job satisfaction and organizational commitment.”

The good, moderate level of stress is when the demands of a situation roughly match the abilities of the person to deal with them:

Under what circumstances is ‘stress’, that is, high demands, good or bad?

See the summary table at the top of this post.

How can stress best be managed?

A meta-analysis of occupational stress management interventions found that cognitive-behavioural interventions (CBT) are the most effective.4

A great book which outlines a self-help CBT program for stress and anxiety management is Overcoming Anxiety. Or you can get CBT online through Lantern.

You can also take the Epstein Stress Management Inventory for Individuals for free, which will tell you how well you manage stress in each of four skill areas. This can help you target which skills to improve.

Sources surveyed

- American Psychological Association: Chronic Stress

- American Psychological Association: Stress Myths

- Booth, Joanne, et al. “Evidence of perceived psychosocial stress as a risk factor for stroke in adults: a meta-analysis.” BMC neurology 15.1 (2015): 1.

- Epstein, Robert. “The Upside of Stress: Why Stress Is Good for You, and How to Get Good at It.” Scientific American Mind 26.4 (2015): 70-70.

- Falk, Anders, et al. “Job strain and mortality in elderly men: social network, support, and influence as buffers.” American journal of Public health 82.8 (1992): 1136-1139.

- Fishta, Alba, and Eva-Maria Backé. “Psychosocial stress at work and cardiovascular diseases: an overview of systematic reviews.” International archives of occupational and environmental health 88.8 (2015): 997-1014.

- Fullagar, Clive J., Patrick A. Knight, and Heather S. Sovern. “Challenge/skill balance, flow, and performance anxiety.” Applied Psychology 62.2 (2013)

- Johnson, Jeffrey V., and Ellen M. Hall. “Job strain, work place social support, and cardiovascular disease: a cross-sectional study of a random sample of the Swedish working population.” American journal of public health 78.10 (1988): 1336-1342.

- Johnson, Jeffrey V., Ellen M. Hall, and Töres Theorell. “Combined effects of job strain and social isolation on cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality in a random sample of the Swedish male working population.” Scandinavian journal of work, environment & health (1989): 271-279. Health1989;15:271–9.](http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2772582)

- Kavanagh, Jennifer. Stress and Performance A Review of the Literature and its Applicability to the Military. RAND CORP SANTA MONICA CA, 2005.

- Keller, Abiola, et al. “Does the perception that stress affects health matter? The association with health and mortality.” Health psychology 31.5 (2012): 677.

- Kuper, Hannah, and Michael Marmot. “Job strain, job demands, decision latitude, and risk of coronary heart disease within the Whitehall II study.”Journal of epidemiology and community health 57.2 (2003): 147-153.

- McGonigal, Kelly. The upside of stress: Why stress is good for you, and how to get good at it. Penguin, 2015.

- Poulin, Michael J., and E. Alison Holman. “Helping hands, healthy body? Oxytocin receptor gene and prosocial behavior interact to buffer the association between stress and physical health.” Hormones and behavior 63.3 (2013): 510-517.

- Poulin, Michael J., et al. “Giving to others and the association between stress and mortality.” American journal of public health 103.9 (2013): 1649-1655.

- Richardson, Katherine M., and Hannah R. Rothstein. “Effects of occupational stress management intervention programs: a meta-analysis.” Journal of occupational health psychology 13.1 (2008): 69.

- Sainani, Kristin. Why you should stop sweating everyday aggravations and embrace the benefits of stress. Stanford Magazine.

- Schneiderman, Neil, Gail Ironson, and Scott D. Siegel. “Stress and health: psychological, behavioral, and biological determinants.” Annual review of clinical psychology 1 (2005): 607.

- Sherman, Gary D., et al. “Leadership is associated with lower levels of stress.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109.44 (2012): 17903-17907.

- US National Institute of Mental Health fact sheet on stress

- World Health Organisation: Stress at the workplace

Notes and references

- Johnson, Jeffrey V., and Ellen M. Hall. “Job strain, work place social support, and cardiovascular disease: a cross-sectional study of a random sample of the Swedish working population.” American journal of public health 78.10 (1988): 1336-1342.

- Johnson, Jeffrey V., Ellen M. Hall, and Töres Theorell. “Combined effects of job strain and social isolation on cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality in a random sample of the Swedish male working population.” Scandinavian journal of work, environment & health (1989): 271-279.

- Falk, Anders, et al. “Job strain and mortality in elderly men: social network, support, and influence as buffers.” American journal of Public health 82.8 (1992): 1136-1139.

- Though note that social support buffering against the negative effects of stress wasn’t confirmed in Kuper, Hannah, and Michael Marmot. “Job strain, job demands, decision latitude, and risk of coronary heart disease within the Whitehall II study.”Journal of epidemiology and community health 57.2 (2003): 147-153.↩

- “Helping others predicted reduced mortality specifically by buffering the association between stress and mortality.”

Poulin, Michael J., et al. “Giving to others and the association between stress and mortality.” American journal of public health 103.9 (2013): 1649-1655. - Poulin, Michael J., and E. Alison Holman. “Helping hands, healthy body? Oxytocin receptor gene and prosocial behavior interact to buffer the association between stress and physical health.” Hormones and behavior63.3 (2013): 510-517.↩

- “Helping others predicted reduced mortality specifically by buffering the association between stress and mortality.”

- Job demands were measured with the following questions:

- Do you have to work very fast?

- Do you have to work very intensively?

- Do you have enough time to do everything?

- Do different groups at work demand things from you that you think are hard to combine?↩

- Richardson, Katherine M., and Hannah R. Rothstein. “Effects of occupational stress management intervention programs: a meta-analysis.” Journal of occupational health psychology 13.1 (2008): 69.↩