Part 6: Which jobs help people the most?

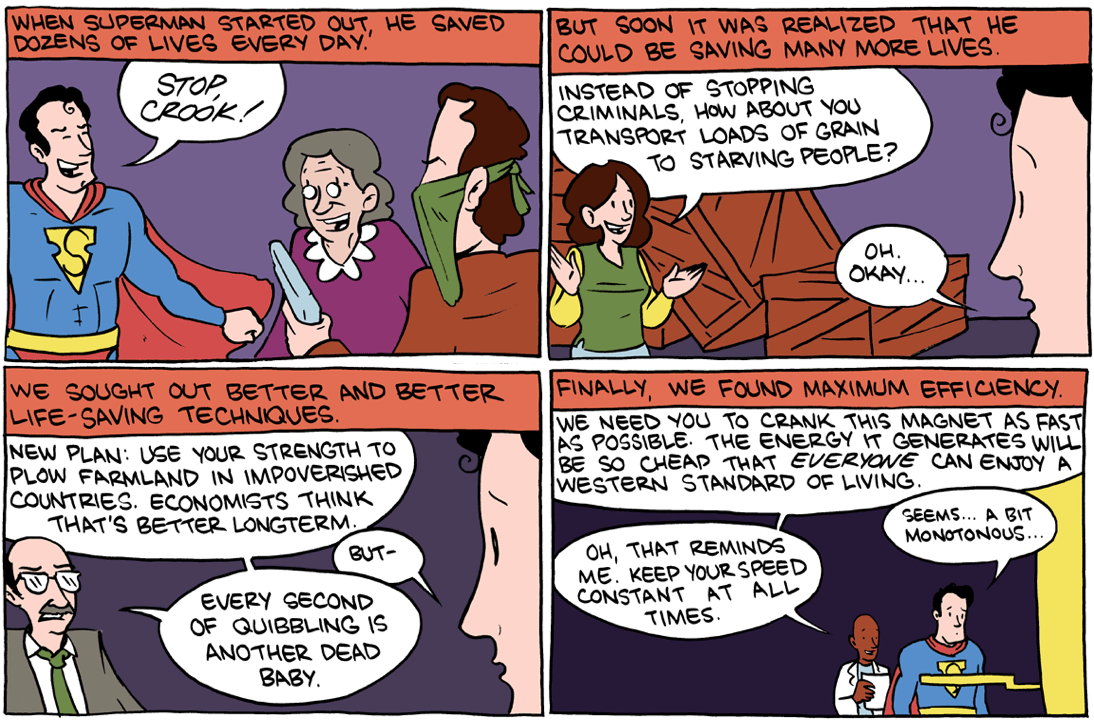

Many people think of Superman as a hero. But he may be the greatest example of underutilised talent in all of fiction. It was a blunder to spend his life fighting crime one case at a time; if he’d thought a little more creatively, he could have done far more good. How about delivering vaccines to everyone in the world at superspeed? That would have eradicated most infectious disease, saving hundreds of millions of lives.

Here we’ll argue that a lot of people who want to “make a difference” with their career fall into the same trap as Superman. College graduates imagine becoming doctors or teachers, but these may not be the best fit for their particular skills. And like Superman fighting crime, these paths are often limited in the amount they could potentially contribute to solving a problem.

In contrast, Nobel Prize winner Karl Landsteiner discovered blood groups, enabling hundreds of millions of lifesaving operations. He would have never been able to carry out that many surgeries himself.

Below we’ll introduce five ways you could use your career to help tackle the social problems you want to help work on (which we identified in the previous article): earning to give, communicating ideas, research, government and policy, and organisation-building. You can think of each of these as a valuable skill set that can help you make a bigger contribution to solving global problems.

To get even more ideas, take a look at our longer list of the highest-impact career paths our research has found so far.

Reading time: 20 minutes.

The bottom line

- Once you’ve chosen a problem, as we covered in the previous article, the next step is to work out how best to contribute to solving it.

- Think broadly about the paths where you can make the biggest contribution, including research, communicating ideas and community-building, taking high-earning jobs to donate to charity, government and policy, and organisation-building.

- Focus on the approaches that are most needed in your problem area. Some problems are best solved through changing policy. Others most need research, while others require funding, and so on.

- Ultimately, in the long term you want to find the option that does best on a combination of (i) how pressing the problem is, (ii) how large your contribution will be, (iii) your degree of personal fit, and (iv) fit with your other personal goals.

Table of Contents

- 1 Approach 1: Earning to give

- 2 Approach 2: Communicating ideas

- 3 Approach 3: Research

- 4 Approach 4: Government and policy

- 5 Approach 5: Building organisations

- 6 More ideas for impactful careers

- 7 A word of caution: power, harm, and corruption

- 8 Which is the right approach for you?

- 9 Conclusion: in which job can you help the most?

- 10 Apply this to your own career

- 11 Recap of our career guide so far

- 12 How can I put myself in the best position to get a high-impact job?

- 13 Want to come back later?: Get the guide as a free book

Approach 1: Earning to give

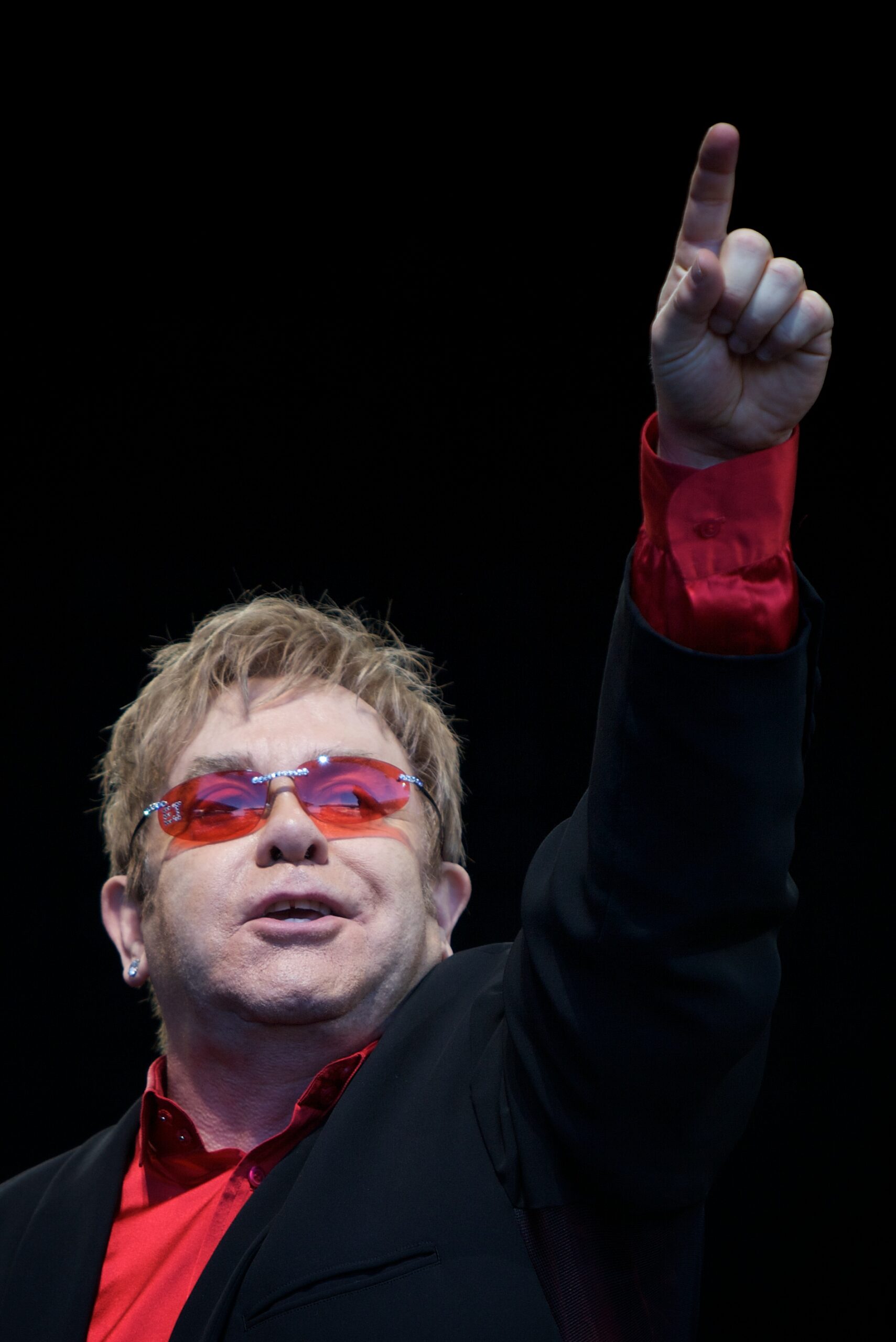

Would Elton John have done more good if he’d worked at a small nonprofit? We don’t normally think of becoming a rockstar as a path to doing good, but (quite apart from the value of his music!) Elton John has saved the lives of thousands of people by reducing the spread of HIV/AIDs.1

So here’s one way of doing more good that’s not normally put on the table: earning to give.

We often meet people who are interested in taking a higher-earning job, like software engineering, but are worried they won’t make a difference if they do. Part of the reason is that we don’t usually think of earning more money as a path for people who want to do good. However, there are many effective organisations that have no problem finding enthusiastic staff, but don’t have the funds to hire. People who are a good fit for a higher-earning option can donate to these organisations, making a large indirect contribution.

We define “earning to give” as working in a job with a neutral or positive direct impact, which pays more than what someone would have done otherwise, and while donating a large fraction of the extra earnings (typically 20–50% of the total salary) to organisations they think are highly effective.

Earning to give is not just for people who want to work in the highest-paying industries. Anyone who aims to earn more in order to give more is on this path. But if you’re a good fit for a higher-earning path, it could be one of your higher-impact options.

Consider the story of Julia and Jeff, a couple from Boston with three children. Through his relationship with Julia, Jeff became interested in using his career for good. Jeff used to work as a research technician. He decided to train up to become a software engineer, and eventually got a job at Google. They were able to earn more than twice as much, so they started to donate about half their income to charity each year.2

By doing this, they may have had more impact than they could by working directly in a nonprofit. Compare Jeff’s impact to that of the CEO of a nonprofit:3

| Google software engineer | Non-profit CEO | |

|---|---|---|

| Salary | $250,000 | $65,000 |

| Donations | $125,000 | $0 |

| Money to live on | $125,000 | $65,000 |

| Direct impact of work | Neutral | Very positive |

Jeff could live on about two times as much as he would have earned in the nonprofit sector, and still donate enough to fund the salaries of about two nonprofit CEOs. Jeff’s guess is that the direct impact of his job was approximately neutral. He also thinks he became happier in his work because he enjoys engineering.

Moreover, Jeff and Julia could switch their donations to whichever organisations were most in need of funds at any given time based on their research, whereas it’s harder to change where you work. This flexibility is particularly valuable if you’re uncertain about which problems will be most pressing in the future.

Making this much difference is possible because (as we saw earlier) we live in a world with huge income inequality — it’s possible to earn several times as much as a teacher or nonprofit worker, and vastly more than the world’s poorest people. At the same time, hardly anyone donates more than a few percent of their income,4 so if you are willing to do so, you can have an amazing impact in a very wide range of jobs.

Earlier, we also saw that any college graduate in a developed country can have a major impact by giving 10% of their income to an effective charity. The average graduate earns $77,000 per year over their life, and 10% of that could save about 40 lives if given to Against Malaria Foundation, for example.

If you could just earn 10% more, and donate the extra, then that’s twice as much impact again. And if you think there are better organisations to fund than Against Malaria Foundation — perhaps working on different problems, or doing research, or communicating important ideas — the impact is even higher.

Since we introduced the concept of “earning to give” in 2011, hundreds of people have taken it up and stuck with it. Some give around 30% of their income, and a few even give more than 50%. Collectively, they’ll donate tens of millions of dollars to high-impact charities in the coming years. In doing so, they are funding passionate people who want to contribute directly, but who otherwise wouldn’t have the resources to do so.

One of the people we advised in 2011, Matt, donated over $1 million while still in his 20s, and was featured in the New York Times. He found his new job more enjoyable too.

“80,000 Hours' career advice has been very helpful — especially in suggesting ways to improve my wellbeing at work.”

Should you earn to give?

Earning to give has been one of our most memorable and controversial ideas, attracting media coverage in the BBC, Washington Post, Daily Mail, and many other outlets.

For this reason, many people think it’s our top recommendation. But it’s not.

We see earning to give mostly as a baseline. It’s a path that many could pursue and do a lot of good — on the scale of saving 100 lives or more, as we just argued.

But we think that most of our readers can have an even greater impact again by pursuing one of the other approaches below. Overall, for people we speak to one-on-one, we only think about 10% should earn to give.

In fact, in 2022, Jeff left his high-paying job at Google. He’s now a researcher at the Nucleic Acid Observatory, building a wastewater monitoring system that he hopes will help detect pandemics before they start. Jeff and Julia are still going to donate over 30% of their income — but given Jeff’s lower salary, they expect most of their positive impact to come directly from their work.

When is earning to give especially promising?

- You’re a good fit for a higher earning option, like Jeff was for software engineering, and you’re not a good fit for other impactful options. (Definitely don’t become a software engineer if you’d hate it!)

- There’s a particular job you really want to do for other reasons where you think you can make significant donations. For instance, you might be someone who’s always wanted to be a doctor, or you might need a higher-earning job to support your family.

- You think a higher-earning option will be good for building skills (for use in more direct work later on), and earning to give could help you to stay engaged with social impact while you do so. For example, working at a tech startup can help you learn organisation-building skills that are useful when running nonprofits. (In the next article we explain why it’s important to gain “career capital.”)

- You’re very uncertain about which problems are most pressing. Earning to give provides flexibility because you can easily change where you donate, or even save the money and give later. (Though money isn’t the only thing that’s transferable! Many skills — including those we cover below — can easily be transferred across problem areas.)

- You want to contribute to an area that is particularly funding-constrained rather than primarily talent constrained.

Common objections to earning to give

We don’t recommend taking a job that does harm in order to donate the money, and we’ve written an entire article about why.

In practice, most people who earn to give work in the fields of technology, asset management, medicine, or consulting, and we think there are many positions in these industries that have roughly neutral or a small positive impact. For instance, many (but not all) financial traders make profits at the expense of other traders, so they’re moving money around, mostly from rich people to other rich people.

Of course, some high-earning jobs can cause a lot of harm. A particularly stark illustration is Sam Bankman-Fried. Sam founded a cryptocurrency exchange with the stated goal of earning to give. In fact, we featured him on our website as an example of someone pursuing a positive career! But Sam ended up being charged with fraud.

We’ve written more about Sam and the possible harm of high-earning careers. The bottom line is: while we think you can do a lot of good through earning to give, we think doing harm for the greater good is almost never a good idea, even if you think the donations might outweigh the costs of a harmful career.

Won’t people earning to give end up being influenced by their peers to spend the money on luxuries rather than donating? We were worried this would happen when we first introduced the idea, but it hasn’t happened as often as you might think. Hundreds of people are pursuing earning to give, and while some have left because they thought they could do more good elsewhere, surprisingly few (that we know of) have simply given up their plans to donate. In part, this is because many people pursuing earning to give made public pledges of their intentions to donate, often through Giving What We Can. The existence of a community that earns to give also makes it much easier to stick with today.

But if you try to earn vast sums of money, there’s a much more substantial risk: that power corrupts. For this reason, we’re more concerned about people who try to earn as much as possible, to the exclusion of all else. We’d suggest publicly precommitting to making donations. And, if you do end up with a lot of money, you should set up safeguards to help make sure you use the money responsibly — such as a board, formal governance structures, and advisors who can keep you in check. Read more about the risk of being corrupted by a higher-earning career.

In that case, don’t do it. We only recommend earning to give if it’s a good fit. Just bear in mind, as we covered previously, that you can become interested in more jobs than you might think.

To learn more about how best to earn to give, its advantages, and major arguments against, see our full article:

Approach 2: Communicating ideas

Consider the following options:

- Earn to give yourself.

- Persuade two friends to earn to give.

The second path does more good — in fact, probably about twice as much. This illustrates the power of communication careers.

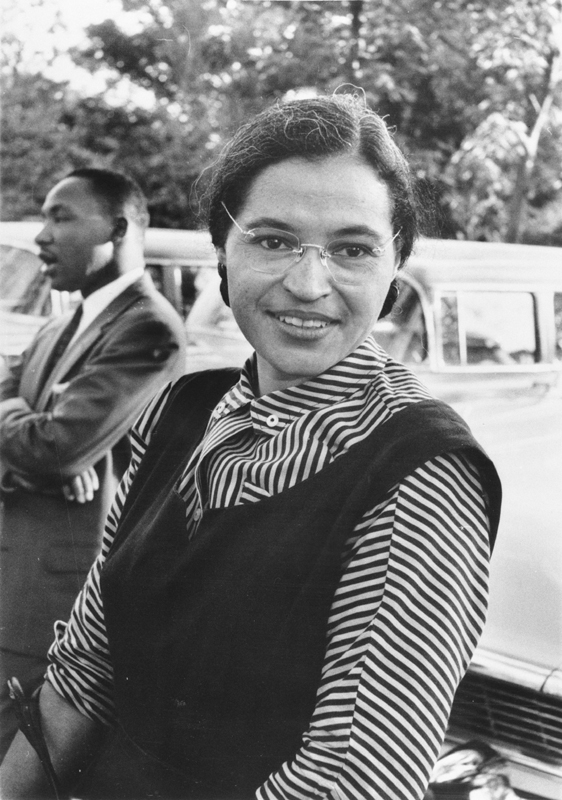

Many of the highest-impact people in history have been communicators and advocates of one kind or another — people who spread important ideas and solutions to pressing problems.

Take Rosa Parks, who refused to give up her seat to a white man on a bus, sparking a protest which led to a Supreme Court ruling that segregated buses were unconstitutional. Parks was a seamstress in her day job, but in her spare time she was very involved with the civil rights movement. After she was arrested, she and the NAACP worked hard and worked strategically, staying up all night creating thousands of fliers to launch a total boycott of buses in a city of 40,000 African Americans, while simultaneously pushing forward with legal action. This led to major progress for civil rights.

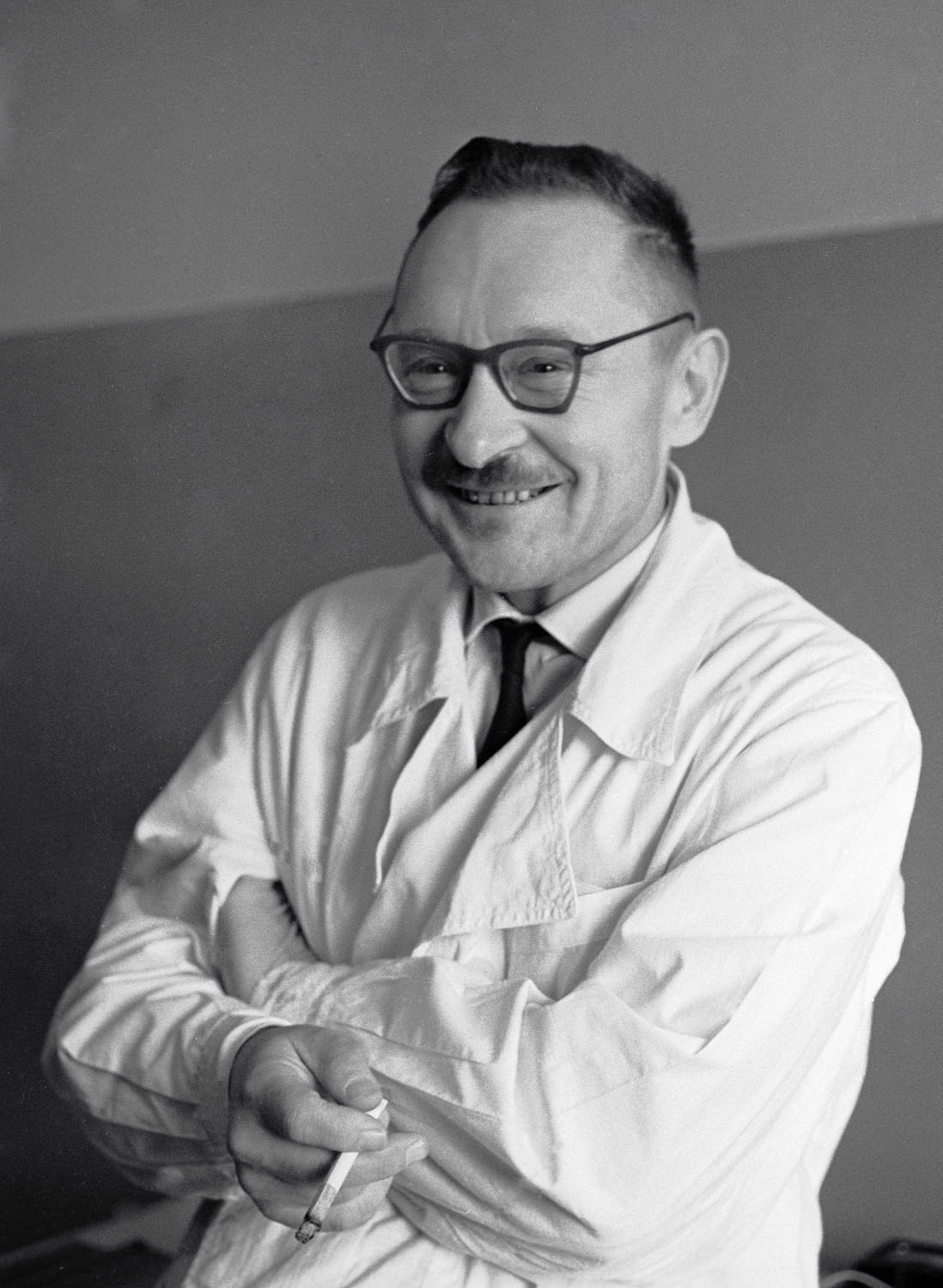

There are also many examples you don’t hear about, like Viktor Zhdanov, who was arguably one of the highest-impact people of the 20th century.

In the 20th century, smallpox killed around 400 million people — far more than died in all the century’s wars and political famines. Credit for the elimination often goes to D.A. Henderson, who was in charge of the World Health Organization’s smallpox elimination programme. However, the programme already existed before Henderson was brought on board. In fact, he initially turned down the job. The programme would probably have eventually succeeded even if Henderson hadn’t accepted the position.

Zhdanov single-handedly lobbied the WHO to start the elimination campaign in the first place. Without his involvement, it would not have happened until much later, and possibly not at all.

So why has communicating important ideas sometimes been so effective?

First, ideas can spread quickly, so communicating them is a way for a small group of people to have a large effect on a problem. A small team can launch a social movement, lobby a government, start a campaign that influences public opinion, or just persuade their friends to take up a cause. In each case, they can have a lasting impact on the problem that goes far beyond what they could achieve directly.

Second, spreading important ideas in a careful, strategic way is neglected. This is because there’s usually no commercial incentive to spread socially important ideas. Instead, advocacy is mainly pursued by people willing to dedicate their careers to making the world a better place. Moreover, the ideas that are most impactful to spread are those that aren’t yet widely accepted. Standing up to the status quo is uncomfortable, and it can take decades for opinion to shift. This means there’s also little personal incentive to stand up for them.

Communicating ideas is also an area where the most successful efforts do far more than the typical efforts. The most successful advocates influence millions of people, while others might struggle to persuade more than a few friends. This means if you’re an exceptionally good fit for communicating ideas, it’s often the best thing you can do, and you’re likely to achieve far more by doing it yourself than you could by funding someone to engage in communication or advocacy on your behalf.

Communication careers can be pursued as a full-time job (such as many jobs in the media), as part of a wider role (like an academic who does science communication), or alongside almost any job (like Rosa Parks).

Communication careers are defined by their focus on spreading ideas on a big scale, but it’s also possible to have a similar impact on a more person-to-person level as a community builder.

For instance, the American women’s rights activist Susan B. Anthony hated writing. So while her cofounder at the Women’s Loyal National League, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, was a powerful communicator — writing long books and editing their weekly newsletter — Anthony primarily focused on organising and building a community.

Anthony’s work running events, talking to activists, and building the suffragist community in the United States eventually led to the 19th amendment to the US Constitution, guaranteeing all adult women the right to vote — it’s often called the “Anthony Amendment” in her honour.

Community building often works well as a part-time position. For instance, Kuhan was a student at Stanford when they came across 80,000 Hours, and realised the importance of reducing existential risks. However, they also saw there were no organisations on campus focusing on that idea. So they founded the Stanford Existential Risk Initiative, which runs courses and conferences about the topic to build a community of students aiming to work on these risks.

“I remember when I first opened up 80,000 Hours, I was like, This is exactly what I've been looking for. This is incredible.”

If you’re interested in pursuing a communication career, see our full article:

Approach 3: Research

People often pan academics as Ivory Tower intellectuals whose writing has no impact. And we agree there are many problems with academia that mean researchers achieve less than they could. However, we still think research is often high impact, both within academia and outside it.

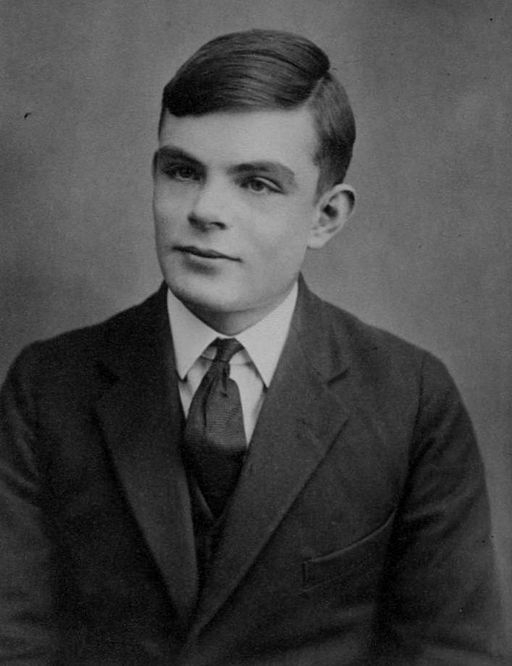

Along with communicators, many of the highest-impact people in history have been researchers. Consider Alan Turing. He was a mathematician who developed code-breaking machines that allowed the Allies to be far more effective against Nazi U-boats in World War II. Some historians estimate this enabled D-Day to happen a year earlier than it would have otherwise.5 Since World War II resulted in 10 million deaths per year, Turing may have saved about 10 million lives.

And he invented the computer.

Turing’s example shows that research can be both theoretical and high impact. Much of his work concerned the abstract mathematics of computing, which wasn’t initially practically relevant, but became important over time.

On the applied side, we saw lots of examples of high-impact medical research earlier in this guide.

Of course, not everyone will be an Alan Turing, and not every discovery gets adopted. Nevertheless, we think that in some cases, research can be one of the best ways to have an impact. Why?

First, when new ideas are discovered, they can be spread incredibly cheaply, so it’s a way that a single career can change a field. Moreover, new ideas accumulate over time, so research contributes to a significant fraction of long-run progress.

However, only a relatively small fraction of people are engaged in research. Only 0.1% of the population are academics,6 and the proportion was much smaller throughout history. If a small number of people account for a large fraction of progress, then on average each person’s efforts are significant.

Second, because there’s little commercial incentive to do research relative to its importance, if you do care more about social impact than profit, then it’s a good opportunity to have an edge. Most researchers don’t get rich, even if their discoveries are extremely valuable. Turing made no money from the discovery of the computer, whereas today it’s a multibillion-dollar industry. This is because the benefits of research come a long time in the future, and can’t usually be protected by patents.

In fact, the more fundamental the research, the harder it is to commercialise, so, all else equal, we’d expect fundamental research to be more neglected than applied research, and therefore higher impact. On the other hand, applied issues can be more urgent — breakthroughs like the microscope can let us make fundamental breakthroughs faster — so it’s hard to say whether applied or fundamental research has a higher impact on average.

So in theory, research can be very high impact. But does research actually help with the most pressing problems facing the world today?

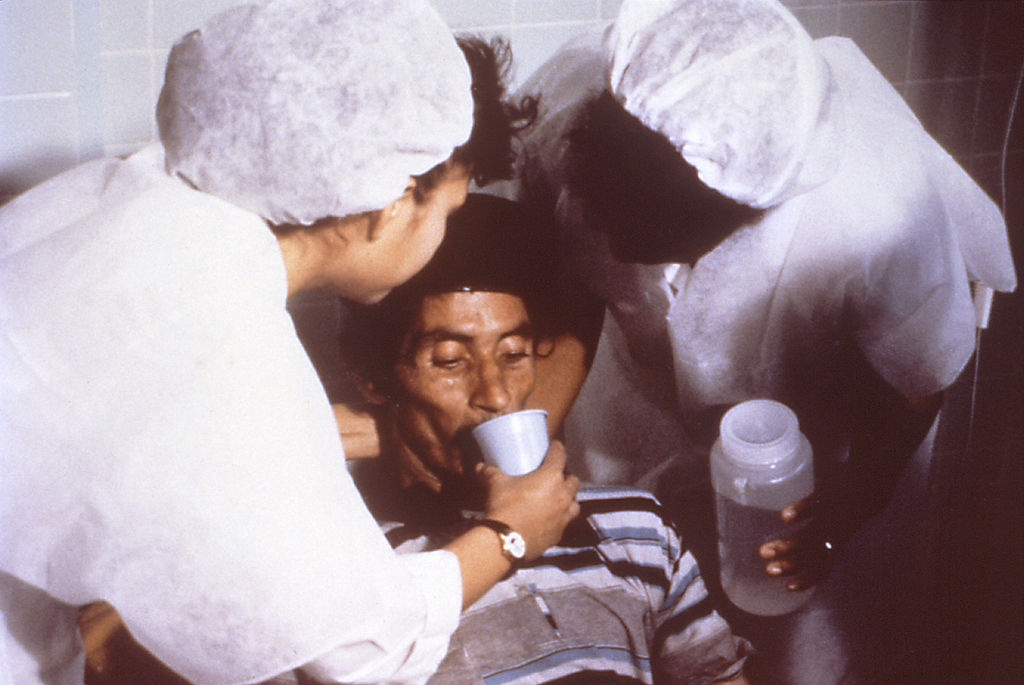

We think it does. When you look at the problems we’re most concerned about — like preventing future pandemics or reducing risks from AI systems — many are mainly constrained by a need for additional research.

For example, research could help us develop ways to decrease the time it takes to go from a novel pathogen to a safe, widely distributed vaccine. As another example, technical machine learning research could help us build safeguards into AI systems to prevent dangerous behaviour. For more ideas, and to get a sense of what you might be able to work on in different fields, see this list of potentially high-impact research questions, organised by discipline.

Like communicating ideas, research is especially promising when you’re a very good fit, because the best researchers achieve much more than the median. Most papers only have one citation, whereas the top 0.1% of papers have over 1,000 citations. And when we did a case study on biomedical research, remarks like this were typical:

One good person can cover the ground of five, and I’m not exaggerating.

If you might be a top 20% researcher in a topic that’s relevant to a pressing problem area, then it’s likely to be one of your most impactful options. And if you might be exceptional in an academic field (maybe, top few percent), even if you can’t see now how it’ll be useful, that’s an option you should probably seriously consider.

While lots of research happens in academia, there are also many research positions elsewhere. For example, many private companies develop crucial technology — BioNTech is now famous for developing the first COVID vaccine7 — while think tanks often do important research in policy.

Example: Neel was doing an undergraduate degree in maths when he decided that he wanted to work in AI safety. Our team was able to introduce Neel to researchers in the field, and helped him secure internships in academic and industry research groups. This helped him see AI safety as a concrete career path and that, despite scepticism of longtermism, AI posed a major risk to even people alive today. Neel didn’t feel like he was a great fit for academia — he hates writing papers — so he applied to roles in commercial AI research labs. He’s now a research engineer at DeepMind. He works on mechanistic interpretability research which he thinks could be used in the future to help identify potentially dangerous AI systems before they can cause harm.

“Talking to 80,000 Hours was really helpful for seeing AI safety research as a more concrete and realistic career path, and deciding to take initial steps towards it.”

See our full guide to learning to do high-impact research, both within and outside academia:

Don’t forget supporting positions

Becoming an academic administrator doesn’t sound like a high-impact career, but that’s exactly why it is. Research requires administrators, managers, grantmakers, and communicators to make progress. Many of these roles require very capable people who understand the research, but because they’re not glamorous or highly paid, it can be hard to attract the right people. For this reason, if a role like this is a good fit for you, then it can be promising. What ultimately matters is not who does the research, but that it gets done.

A hero of ours is Seán Ó hÉigeartaigh. He studied for a PhD in comparative genomics, but ultimately decided to pursue academic project management. He became a manager at the Future of Humanity Institute, which undertakes neglected research into emerging existential risks, like risks from AI and engineered pandemics. He did a huge amount of work behind the scenes to keep things running as funding rapidly grew. When there was an opportunity to start a new research group in Cambridge, he used what he’d learned to lead efforts there too — at one point managing both groups. The field would have moved much more slowly without his management.

If you’re interested in positions like these, the best path is usually to pursue a PhD, pick a field, then apply to research groups. If you want to enable great research, you need a combination of familiarity with the field and operations skills. Learn more about research management careers.

Approach 4: Government and policy

When we think of careers that “do good,” we might not first think of becoming an unknown government bureaucrat. But senior government officials often oversee budgets of tens or even hundreds of millions. If you could enable those budgets to be spent just a couple of percent more effectively, that would be worth millions of extra dollars spent on those programmes. And more broadly, the scale of the influence in government positions can be enormous.

For instance, Suzy Deuster wanted to become a public defender to ensure disadvantaged people have good legal defence. She realised that in that role she might improve criminal justice for perhaps hundreds of people over her career, but by changing policy she might improve the justice system for thousands or even millions. Even if the impact per person is smaller, the numbers involved give her the chance of making a greater impact. She was able to use her legal background to enter government, and now works in the Executive Office of the President of the US on criminal justice reform, and from there she can explore other areas of policy in the future.

Government is often crucial in addressing many of the issues we most recommend people work on, because they are the only institutions that create and enforce laws and regulation.

For example, only governments can do something like ban battery cages for egg-laying hens.

They can also act to solve coordination problems that are difficult for individual actors to tackle. When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, contact tracing was essential to slowing its spread, but it wasn’t in any individual’s self-interest to participate. Governments stepped in to provide contact tracing services, benefiting society as a whole.

Positions in policy require a wide range of skill types, so there should be some high-impact options for nearly everyone.

See our full guide to learning how to have an impact in policy:

How to enter government and policy careers

Approach 5: Building organisations

When most people think of careers that “do good,” the first thing they think of is working at a charity.

The thing is, lots of jobs at charities just aren’t that impactful.

Some charities focus on programmes that don’t work, like Scared Straight, which actually caused kids to commit more crimes. Others focus on ways of helping that don’t have much leverage, like Superman fighting criminals one-by-one, or Dr Landsteiner focusing on performing surgeries rather than doing the work to discover blood groups.

Another problem is that many people want to work at organisations that are more constrained by funding than by the number of people enthusiastic to work there. This means if you don’t take the job, it would be easy to find someone else who’s almost as good. Think of a lawyer who volunteers at a soup kitchen. It may be motivating for them, but it’s hardly the most effective thing they could do. Donating one or two hours of salary could pay for several other people to do the work instead. Or they could do pro bono legal work, and contribute in a way that makes use of their valuable skills.

However, there are plenty of other situations when working for a nonprofit is the most effective thing to do.

Nonprofits can tackle issues that other organisations can’t. They can carry out research that doesn’t earn academic prestige, or do political advocacy on behalf of disempowered groups such as animals or future generations, or provide services that would never be profitable within the market.

And there are lots of nonprofits doing great work that really need more people to help build and scale them up. There are also lots of niches that aren’t being filled, where we need new nonprofits to be set up to tackle them.

More broadly, helping to build an organisation can be a route to making a big contribution, because organisations allow large groups of people to coordinate, and therefore achieve a bigger impact than they could individually. Moreover, if you help build or start an effective organisation, it can continue to have an impact even after you leave.

And if you can help make an already existing and impactful organisation somewhat more effective, that can also be a route to a big impact.

Clare joined Lead Exposure Elimination Project (LEEP) as its third staff member. She thought that joining LEEP would help build her career capital — especially her skills and connections — and, more importantly, that lead exposure in low- and middle-income countries is an important, solvable, and highly neglected problem. Since joining, Clare has developed LEEP’s programmes and managed the team implementing them, as well as led the hiring for crucial new staff. LEEP has since started working with governments and industry in 16 countries, and has successfully advocated for the government in Malawi to monitor levels of lead in paints.

These organisations don’t even need to be nonprofits — some social impact projects are better structured as businesses, and could also include think tanks, research groups, advocacy groups, and so on.

For instance, Send Wave enables African migrant workers to transfer money to their families through a mobile app for fees of 3%, rather than 10% fees with Western Union. So for every $1 of revenue they make, they make some of the poorest people in the world several dollars richer. Within three years, they’d already had an impact equivalent to donating millions of dollars, and they’ve grown even more since then. The total size of the market is hundreds of billions of dollars — several times larger than all foreign aid spending. If they can continue to slightly accelerate the rollout of cheaper ways to transfer money, it’ll have a big impact.

Organisation-building careers are a good fit for people who can develop skills in areas like operations, people management, fundraising, administration, software systems, and finance.

Pursuing this path usually means first focusing on building some of these skills (which can be done at any competent organisation), and then later on using them to contribute to the organisations you think are most impactful.

To find impactful organisations, think about which problems you think are most pressing, and then try to identify the best organisations addressing those problems. (In our problem profiles, we list recommended organisations to give you some ideas, or see this list.) Finally, try to identify those that have a pressing need for your skills and a role that might be a great fit for you.

See our full guide to learning how to build high-impact organisations:

How to work on organisation building

Or check out our job board.

What about if you want to found an organisation?

One mistake people make is trying to work out which organisations should be founded from their armchair, or by choosing an issue that they just happen to stumble across.

Instead, go and learn about big, neglected social problems. Take a job in the area, do further study, and speak to lots of people working on the problem to find out what the world really needs. You need to get near the edge of an area before you’ll spot the ideas others haven’t, and have the connections you’ll need to execute on those ideas. Learn more in our full profile on founding impactful organisations.

More ideas for impactful careers

These categories aren’t intended to be comprehensive. There are lots of impactful options that don’t naturally fit into them.

For example, experts in information security are sorely needed by organisations working to prevent AI-related and biological catastrophes. There aren’t very many trained information security experts to begin with, and only a few are trying to use their careers to solve these urgent problems.

To see a much longer list of ideas (which still isn’t exhaustive), check out our career reviews page:

Our full list of career reviews

A word of caution: power, harm, and corruption

Sam Bankman-Fried founded the cryptocurrency exchange FTX with the stated goal of earning to give. He briefly became the world’s richest person under 30, and made large donations to pressing causes.8 We previously featured him across our site as a positive example of someone pursuing a high-impact career.

Sam is now charged with fraud, FTX collapsed into bankruptcy, and billions of dollars of customer funds went missing.

This has done a lot of harm to individual depositors and society, both through the money lost and the indirect harms of criminal activity. It may have also harmed the reputation of the causes he was supporting, and the idea of earning to give in general. For our part, we felt betrayed and shaken when we found out what had happened, and ashamed about our past promotion of him (see our mistakes page).

It now seems clear that even if Sam told himself that the rewards justified the risks, that was totally wrong.

How might this be relevant to you? Each of the five paths covered in this article offers ways to substantially increase the amount that you can contribute to solving a problem.

But generally, the greater your ability to contribute, the greater your ability to do harm — whether by making a substantial mistake, supporting the wrong issues, or acting unethically.

Moreover, as you gain more ability to affect the world, you may face more temptations to act badly. “Power corrupts” is a cliché for a good reason.

This might be hard to imagine if you’re at the start of your career, but if you end up in a powerful position in government, running a large organisation, with a degree of fame, or with lots of money, you may face situations where acting ethically will pose a risk of losing the large influence you have — like a politician lying to stay in office. This can be true even if you didn’t originally seek power for your own benefit.

You may also face difficult ethical tradeoffs, such as taking roles you think involve an element of harm in order to achieve a potentially greater positive impact.

And typically, the more influence you have, the harder it will be for people to disagree with you, because they’ll fear the consequences, so you’ll become less able to make good decisions just at the point you most need to.

Working on problems that are unusually important and neglected also further raises the stakes, because if you slip up, you’ve set back a more important issue, and the fact that few other people are working on the issue magnifies your potential for harm.

One key point is that we don’t generally recommend taking jobs or actions you think are harmful for the greater good. We talked about that in the section on earning to give above, but it can come up with whatever approach you choose to take.

There’s a lot more to say about these themes, and we explore them our advanced series:

- How to avoid accidentally making things worse

- Why not to take harmful actions even if you think it’s for the greater good

- Nice norms and cooperation

- Avoiding corruption in earning to give

- What’s the definition of social impact?

It’s also one reason why we see building good character as an important part of career capital, which is up next.

Which is the right approach for you?

We’ve now seen that by thinking broadly — considering earning to give, communicating ideas, research, government and policy, and organisation building — there are many ways to make a big contribution to pressing problems.

If you want to choose between these broad categories, how might you approach it?

What’s most crucial is your degree of fit: any of these categories can be an impactful career, if you’re good at it.

Throughout this article, there is a vital general principle to bear in mind: the most successful people in a field have far more impact than the typical person. For instance, a landmark study of expert performers found:9

A small percentage of the workers in any given domain is responsible for the bulk of the work. Generally, the top 10% of the most prolific elite can be credited with around 50% of all contributions, whereas the bottom 50% of the least productive workers can claim only 15% of the total work, and the most productive contributor is usually about 100 times more prolific than the least.

Just as we saw with choosing a problem, this means the most effective approach for you will be something you enjoy, that motivates you, and is a good fit for your skills.

We sometimes come across people tempted to do a job they’d hate in order to have more impact. That’s likely a bad idea, since they’ll just burn out. Their example could also discourage others from using their careers to do good.

An outstanding charity worker will likely do more good than a mediocre software engineer earning to give, and the reverse is also true.

We cover the importance of personal fit and how to work out which career is best for you in a later article in the series.

But don’t worry if you feel unsure — that’s normal. Finding a career that fits often takes many years. If you’re at the start of your career, it’s fine to just have some vague ideas about where you’re aiming, and make them more specific over time.

And while personal fit is important, it’s also important not to narrow down too early. As we’ve seen, people often underestimate how easily they can become interested in new jobs. So it’s important to explore widely, giving yourself a chance to become interested in new approaches, but then to focus on what’s going well.

You also don’t need to limit yourself to your background so far. 80,000 hours is a long time, so you have a lot of scope to learn new skills.

Putting personal fit aside, note there is no single best approach for every problem. Rather, focus on the approaches that are most needed by the problems you want to solve. For instance, breast cancer doesn’t need more advocacy to promote awareness, because almost everyone is aware that breast cancer is a problem. Instead, it probably needs more skilled researchers to develop better treatments. If you just focus on raising awareness, then your efforts won’t go as far. We try to highlight which skills are most needed within each area in our problem profiles.

Also consider that these approaches are not mutually exclusive, and you can do more than one at the same time or create valuable combinations. For instance, a teacher helps their students (direct impact), but could also develop new educational techniques (research), or tell their students about pressing problems (communicating ideas). We know a teacher who did private tutoring in order to donate more (earning to give). As we’ve seen, often your impact is more about how you use your position than the position itself.

Conclusion: in which job can you help the most?

There are many more paths to helping others in your career than we normally talk about. Elton John started as a singer, and saved thousands of lives through earning to give. Rosa Parks was a seamstress, and helped to trigger the civil rights movement in America through communication and advocacy. Alan Turing was a mathematician who helped to end World War II through research, as well as inventing the computer.

Most people aren’t born rockstars, but even at a normal graduate salary, anyone can have an astonishing impact through earning to give, literally saving hundreds of lives. And it’s often possible to do even more through communicating ideas, research, government and policy, or building organisations.

By expanding the range of options you consider, it’s often possible to find a path that’s not only higher impact, but also a better fit and more satisfying too.

In this way, even if you don’t want to be a doctor or a teacher, it’s possible to do far more good with your career than is normally thought.

Apply this to your own career

Before we move on, make an initial shortlist of high-impact careers you could work towards in the long run. Here’s some ways to generate ideas:

- Go over each approach in this article. Try to generate 2–3 more specific paths within each that might be a good fit for you and meet your other personal criteria. Which might be the best fit for you?

- Take your list of pressing problems from earlier. What do those problems most need? Can you think of any career paths you might be able to take that could help address those needs?

- See our list of career reviews and note down any other ideas there.

- Are there any other paths you’re aware of that you might excel at, or are unique opportunities open only to you? Add them to your list too.

- Imagine your ideal working day, hour by hour. What jobs might fit with that? What job would you do if money were no object, or if you only had 10 years left to live? Does that give you any other ideas for fulfilling longer-term career paths?

The aim at this point is just to come up with more options. We’ll explain how to further narrow down in an upcoming article.

In generating options, err towards including more rather than less. In particular, we often talk to people who only ever really think about jobs that are closely related to their past experience, and that’s often a mistake. For example, you don’t need to have studied anything to do with politics in order to work in government and policy.

It’s often possible to get a job in a new area without specific experience, and even if it takes a couple of years to transition, that can easily be worth it in the context of the rest of your career. This is especially true if you’re an undergraduate — what you’ve studied so far has little bearing on what you might do in the future.

Recap of our career guide so far

Earlier, we saw that an enjoyable and fulfilling job:

- Helps others.

- Is something you’re good at.

- Has the right supportive conditions (e.g. engaging work, supportive colleagues, fit with the rest of your life).

We’ve now also seen that the jobs that most help others:

- Are focused on the most pressing problems — those that are big in scale, neglected, and solvable — as we covered here.

- Take an approach that might let you make a big contribution, such as research, communicating ideas, earning to give, government and policy, and building organisations. That’s what we covered in this article.

- Provide you with the chance to excel. We’ll explain how to work out where you have the best personal fit later on.

Should you sacrifice to do more good?

People often ask us whether they should sacrifice what they enjoy in order to have a greater impact. But as we discussed above, doing good involves less sacrifice than it first seems. A personally satisfying job involves helping others, because that’s fulfilling. And a high-impact job will also need to be personally satisfying — because if you don’t like your job, you probably won’t be good at it and you’ll burn out. So there’s a lot of overlap.

We’ve also seen there are lots of ways to have a big impact, and some of these probably won’t involve much sacrifice. Rather than making sacrifices, the key thing to focus on is finding these highly effective ways to help.

That’s not to say there’s no tradeoff at all. It’s unlikely that the very best career for you personally is also the one that most benefits the world. Ultimately, you’ll have to make a value judgement about how to weigh helping others against your own interests. But fortunately, the tradeoff is less than it first seems.

How can I put myself in the best position to get a high-impact job?

Some people can just walk into their dream job — one that matches all the criteria above — right away. And if you can do that, go for it! But for many others, you’ll need to build your skills, connections, credentials, and character — what we call “career capital.” By doing this, you can open up a wider range of options than just those you think you have today.

In the next article, we’ll look at how to build career capital and best position yourself for long-term success.

Read next: Part 7: Which jobs put you in the best long-term position?

Or see an overview of the whole career guide.

Notes and references

- Elton John regularly tops lists of the most generous celebrities in the UK. His money helped found the Elton John AIDS Foundation.

But it’s unclear how many lives he’s saved.

He gave £26.8 million to charity in 2016, and likely gave similar amounts in other years, so we’d guess he’s given hundreds of millions overall.

How cost effective was this spending? Elton John’s focus has primarily been HIV/AIDS interventions in the developing world. We’d guess that these interventions aren’t as cost effective as the most cost-effective interventions in global health. GiveWell — an independent charity evaluator — found that:

HIV/AIDS is a leading cause of adult deaths in the developing world. Antioretroviral therapy can prolong and improve patients’ lives, and potentially reduce the risk that they will infect others, for a cost of several hundred dollars per year. We are revisiting the question of how this compares to the cost-effectiveness of other global health interventions. There are other interventions (including preventative interventions) that may be more cost-effective. We have not found a charity we can confidently recommend that focuses on HIV/AIDS.

GiveWell reviewed three specific interventions: condom promotion and distribution, drug treatment with Antiretroviral Therapy (ART), and prevention of mother-to-child transmission.

GiveWell estimated that ART is approximately 1.4 times as cost effective as direct cash transfers. GiveWell’s funding bar (as of March 2023) is that it funds interventions that are around 10 times more cost effective than cash, which would make ART about seven times less cost effective than top interventions in global health. While GiveWell expects that preventative interventions may be more cost effective, they note that evidence for condom promotion and distribution reducing HIV/AIDS transmission, one of the most common interventions in the area, is weak.

Overall, we’d guess that spending on HIV/AIDS interventions in the developing world is around 10 times less cost effective than GiveWell’s top charities.

GiveWell’s estimate of the cost to save a life through its top charities has varied over time between $1,000 and $10,000, and is typically around $3,000–5,000. As of January 2023, you can find GiveWell’s latest estimates of the cost to save a life on its impact page.

As a result, we’d guess Elton John’s AIDS spending saved a life for around $50,000.↩

- In 2012, they donated to 80,000 Hours. They have also donated to related projects such as the Centre for Effective Altruism (where Julia now works) that, like 80,000 Hours, is a project of Effective Ventures Foundation.↩

- The 2012 Watkins Uiberall Report found that (Link:

The median salary for executive directors/CEOs is between $50,000 and $75,000. CEO salaries correlate with organizational budget size. For small organizations, the median salary is between $30,000 and $50,000. Among medium-sized organizations, 36% of CEOs have salaries between $50,000 and $75,000, while 50.5% earn more than $75,000 and 13.5% earn less than $50,000. Among large organizations, 14.2% pay salaries of $100,000 or less; 38.1% pay between $101,000 and $150,000; and 47.7% pay more than $150,000.

Note that this is significantly lower than the median figures reported by the prominent Charity Navigator Annual Survey. This is because Charity Navigator focuses on “mid to large” US charities, which pay substantially higher salaries.↩

“…those with income between $100,000 and $200,000 contribute, on average, 2.6 percent of their income, which is lower compared to those with income either below $100,000 (3.6 percent) or above $200,000 (3.1 percent)”

Charitable Giving in America: Some Facts and Figures. Rates of charitable giving in the US are among the highest in the world.↩

- This BBC article quotes a number of historians (archived link, retrieved 13-June-2016), concluding:

If Turing and his group had not weakened the U-boats’ hold on the North Atlantic, the 1944 Allied invasion of Europe — the D-Day landings — could have been delayed, perhaps by about a year or even longer, since the North Atlantic was the route that ammunition, fuel, food and troops had to travel in order to reach Britain from America.↩

- The number of academics and graduate students in the world↩

- Technically, it was the first vaccine cleared for use by a regulator recognised by the World Health Organization as a stringent regulatory authority.↩

- Sam Bankman-Fried donated to 80,000 Hours early in his career, and FTX donated funds to Effective Ventures group. 80,000 Hours is a project of the Effective Ventures group — the umbrella term for Effective Ventures Foundation and Effective Ventures Foundation USA, Inc., which are two separate legal entities that work together.↩

- Simonton, Dean K. “Age and outstanding achievement: What do we know after a century of research?.” Psychological bulletin 104.2 (1988): 251. PDF↩