#93 – Andy Weber on rendering bioweapons obsolete and ending the new nuclear arms race

#93 – Andy Weber on rendering bioweapons obsolete and ending the new nuclear arms race

By Robert Wiblin and Keiran Harris · Published March 12th, 2021

On this page:

- Introduction

- 1 Highlights

- 2 Articles, books, and other media discussed in the show

- 3 Transcript

- 3.1 Rob's intro [00:00:00]

- 3.2 The interview begins [00:01:13]

- 3.3 Project Sapphire [00:05:57]

- 3.4 Georgia and Moldova [00:17:10]

- 3.5 How did the Nunn-Lugar program succeed? [00:23:09]

- 3.6 Bioweapons programs [00:29:26]

- 3.7 Tech that could make bioweapons obsolete [00:42:31]

- 3.8 Using this tech to prevent natural pandemics [00:48:01]

- 3.9 Chances that COVID-19 escaped from a research facility [01:01:55]

- 3.10 How people in U.S. defense circles think about nuclear winter [01:15:16]

- 3.11 Can a president unilaterally launch nuclear weapons? [01:18:24]

- 3.12 Top nuclear security priorities for the Biden administration [01:20:15]

- 3.13 Odds of a great power war between the U.S. and China [01:33:18]

- 3.14 Careers [01:38:59]

- 3.15 Rob's outro [01:53:06]

- 4 Learn more

- 5 Related episodes

During the Cold War, Vozrozhdeniya Island was a top-secret bioweapons testing facility that wasn’t even marked on Soviet maps. Today, it lies abandoned, and if you want to visit – you should probably wear full biohazard equipment.

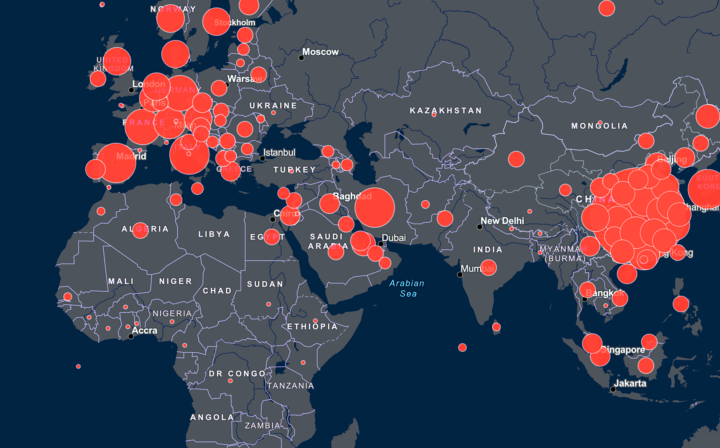

COVID-19 has provided a vivid reminder of the damage biological threats can do. But the threat doesn’t come from natural sources alone. Weaponized contagious diseases — which were abandoned by the United States, but developed in large numbers by the Soviet Union, right up until its collapse — have the potential to spread globally and kill just as many as an all-out nuclear war.

For five years, today’s guest, Andy Weber, was the US’ Assistant Secretary of Defense responsible for biological and other weapons of mass destruction. While people primarily associate the Pentagon with waging wars (including most within the Pentagon itself) Andy is quick to point out that you don’t have national security if your population remains at grave risk from natural and lab-created diseases.

Andy’s current mission is to spread the word that while bioweapons are terrifying, scientific advances also leave them on the verge of becoming an outdated technology.

He thinks there is an overwhelming case to increase our investment in two new technologies that could dramatically reduce the risk of bioweapons, and end natural pandemics in the process: mass genetic sequencing and mRNA vaccines.

First, advances in mass genetic sequencing technology allow direct, real-time analysis of DNA or RNA fragments collected from all over the human environment. You cast a wide net, and if you start seeing DNA sequences that you don’t recognise spreading through the population — that can set off an alarm.

Andy notes that while the necessary desktop sequencers may be expensive enough that they’re only in hospitals today, they’re rapidly getting smaller, cheaper, and easier to use. In fact DNA sequencing has recently experienced the most dramatic cost decrease of any technology, declining by a factor of 10,000 since 2007. It’s only a matter of time before they’re cheap enough to put in every home.

In the world Andy envisions, each morning before you brush your teeth you also breathe into a tube. Your sequencer can tell you if you have any of 300 known pathogens, while simultaneously scanning for any unknown viruses. It’s hooked up to your WiFi and reports into a public health surveillance system, which can check to see whether any novel DNA sequences are being passed from person to person. New contagious diseases can be detected and investigated within days — long before they run out of control.

The second major breakthrough comes from mRNA vaccines, which are today being used to end the COVID pandemic. The wonder of mRNA vaccines is that they can instruct our cells to make any random protein we choose and trigger a protective immune response from the body.

Until now it has taken a long time to invent and test any new vaccine, and there was then a laborious process of scaling up the equipment necessary to manufacture it. That leaves a new disease or bioweapon months or years to wreak havoc.

But using the sequencing technology above, we can quickly get the genetic codes that correspond to the surface proteins of any new pathogen, and switch them into the mRNA vaccines we’re already making. Inventing a new vaccine would become less like manufacturing a new iPhone and more like printing a new book — you use the same printing press and just change the words.

So long as we maintained enough capacity to manufacture and deliver mRNA vaccines, a whole country could in principle be vaccinated against a new disease in months.

Together these technologies could make advanced bioweapons a threat of the past. And in the process humanity’s oldest and deadliest enemy — contagious disease — could be brought under control like never before.

Andy has always been pretty open and honest, but his retirement last year has allowed him to stop worrying about being seen to speak for the Department of Defense, or for the president of the United States – and so we were also able to get his forthright views on a bunch of interesting other topics, such as:

- The chances that COVID-19 escaped from a research facility

- Whether a US president can really truly launch nuclear weapons unilaterally

- What he thinks should be the top priorities for the Biden administration

- If Andy was 18 and starting his career over again today, what would his plan be?

- The time he and colleagues found 600kg of unsecured, highly enriched uranium sitting around in a barely secured facility in Kazakhstan, and eventually transported it to the United States

- And much more.

Get this episode by subscribing to our podcast on the world’s most pressing problems and how to solve them: Type 80,000 Hours into your podcasting app. Or read the transcript below.

Producer: Keiran Harris

Audio mastering: Ben Cordell

Transcriptions: Sofia Davis-Fogel

Highlights

Project Sapphire

Andy Weber: So it started when my auto mechanic asked me — he knew I worked at the embassy — he asked me one day if I was interested in buying some uranium. And at that time, after the breakup of the Soviet Union, I was recently assigned to our embassy in this new country of Kazakhstan, in the original capital of Almaty, and anything was possible, strange things were happening at that time. So I didn’t just dismiss it out of hand. And I spent several months following up on that initial lead.

And frankly, there was a lot of disbelief when I reported this back to Washington. But over time we were able to verify that indeed they had over 600 kg of 90% enriched uranium sitting at a warehouse in northeastern Kazakhstan.

We were concerned about Iran having an enrichment capability, which is a large industrial capability. But had they bought this material, they would have enough for several dozen bombs right away. They wouldn’t have to go through the process of enriching uranium. This was directly weapons-usable material.

There were a lot of risks [in getting it out]. I think the biggest risk we felt was that if we lost the secrecy, then the material would become vulnerable. Especially when we have people on the ground packaging the material. We didn’t want the bad guys — whether it’s organised crime, or operatives from other countries — to know that we were loading this material, which was definitely most vulnerable when it was mobile, when it was loaded onto trucks, in preparation for the convoy to the airport.

How did the Nunn-Lugar program succeed?

Andy Weber: Well, this is a prevention program, right? And so you don’t get credit for the catastrophe that didn’t happen, but it is an extraordinary story. I mean, it was the vision of Senators Richard Lugar and Sam Nunn that created this program, gave it to the Pentagon to run, and then at first the Pentagon was a little reluctant to be involved in working with Russia on this problem. But the reason it was so successful, indeed, the genius of this program, was that it facilitated work directly with the custodians of these weapons and materials.

There were some negotiations in the capital with the foreign ministry, but for the most part, we worked in very remote locations at these WMD facilities and bases throughout Russia and the neighboring countries, directly with the engineers and the security forces who guarded them and the people who felt a responsibility to protect them. So that was the genius, and that’s why we were so successful, because it was a full partnership with our counterparts in those countries.

Bioweapons programs

Andy Weber: Bioweapons — developed during the Cold War by the United States until Nixon canceled our program in 1969, and then the Soviet Union right up until the collapse — were potentially equally devastating to nuclear weapons. They were called the ‘poor man’s atomic bomb.’ It’s easier for a country to develop biological weapons than it is to develop nuclear weapons — it’s essentially the use of infectious disease as a weapon. And this could be devastating. There are different types of diseases with different effects, but the ability to deliver them against a population or on a battlefield or to an individual makes them really an insidious type of weapon.

In the ’80s and ’90s, the primary threat came from the Soviet Union. They grew their program, and when the ink was drying in 1975 on the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention, that’s when they upped their investment in this program, knowing that the United States no longer had one. They sought an advantage. At one point they had about 50 or 60 facilities working on their biological weapons program, 40,000 or 50,000 scientists and engineers. It was a massive, massive effort, and thankfully they never used them.

The threat is different today, but it’s probably greater. And I say that because the technology has advanced, and the Soviet program applied sort of rudimentary molecular biology in ways to make viruses and bacteria more effective as weapons. But now the tools are much easier to use, more precise. So you can enhance the virulence, the transmissibility, the environmental hardiness of pathogens in a way that just wasn’t possible back then. So I’m very, very concerned today that especially North Korea — which we know a lot about their missile and nuclear weapons programs, they have an advanced biological weapons program. I’m concerned that Russia still continues elements of its biological weapons program. It’s on a much smaller scale, but you don’t need a lot of biological weapons to kill potentially billions of people.

The advances in technology that could stop bioweapons and natural pandemics

Andy Weber: So it starts with early warning. So think about some of the revolution in diagnostics and testing that’s been happening because of COVID. So imagine in-home testing, every morning when you’re brushing your teeth, you breathe into a tube and you know if you’re infected with a virus and it tells you which one. That’s sort of the early detection that’s now possible. You might have it hooked up to your smartphone and it would report into a public health surveillance system. And so you would know if it’s just an isolated individual or if it’s spreading into the community.

So that early warning piece. And then sequencing is becoming so cheap and fast that within 24 hours, you can determine if a person has a respiratory illness, for example. You can test through sequencing for 300 different pathogens, as well as virus X, the unknown, the novel. And those are the sorts of capabilities that we need in order to have that weather map, that prediction of infectious disease outbreaks that allows us to nip them in the bud.

Look at the example of how a Chinese laboratory posted the SARS-CoV-2 sequence I believe on January 11th, and within days, a DARPA-supported company in Boston called Moderna developed this mRNA vaccine prototype. And then it was in phase I trials, just a little over a month later. So using sequences, we can have what I call rapid medical countermeasures — therapeutics and vaccines that are based on the sequence of the pathogen and can be developed and then manufactured quickly. Think sort of nucleic acid 3D printers that could use this digital information — because biology is now digital — and develop and produce these vaccines in a distributed way. So we would, as soon as even a novel or previously unknown pathogen were released, we would in days — or a month at the most — have a countermeasure we can apply to preventing it. So these are the capabilities that while even 10 or 15 years ago may have seemed like science fiction, today they’re upon us. But we need to invest in this overall system of defenses.

Top nuclear security priorities for the Biden administration

Andy Weber: I think that the goal of arms control should be to enhance U.S. security, mutual security, and global security. It’s not some, you know, Pollyanna-ish disarmament thing. It is focused on enhancing our national security, and other countries will have that same selfish interest in enhancing their national security. So the goals should be first and foremost to reduce the risk of nuclear war. And what is it that makes the risk of nuclear war high? I think it’s these smaller, so-called ‘low-yield’ systems on ambiguous delivery platforms, like cruise missiles that are used for conventional weapons and nuclear weapons. It’s these smaller, more tactical systems that are the most dangerous type of nuclear weapon. And so we should focus on eliminating both bilaterally and perhaps among all nuclear weapon possessor states, these most dangerous types of nuclear weapons.

We used to have a bright red line between nuclear operations and conventional operations. Well, there’s been an intentional blurring of the line between conventional and nuclear war. And that is very, very dangerous. They had something that started with president Putin’s policies on nuclear weapons, but then was mimicked by the Trump Administration. So we need to walk away from that concept. Indeed, it’s this very same danger that presidents Reagan and Gorbachev focused on when they adopted the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty in 1987. It was those smaller systems with short flight times that could be used in Europe that the treaty focused on, including ground-launch cruise missiles, which fly low, they’re undetectable. Their missiles are slow, quiet, low to the ground and stealthy — unlike ballistic missiles, which have a big signature upon launch, and your early warning systems can detect them. So those are the ones that I believe are most likely to cause a nuclear war.

If Andy was 18 and starting his career over again today, what would his plan be?

Andy Weber: I’ve had such a privileged career and I continue to be able to work on these issues that I’m so passionate about. I don’t think I would really change anything, but the 21st century is definitely going to be the century of biology. If the 20th century was the nuclear age, the 21st century is going to be the century of biology. So I would be so excited to be involved in biotechnology, bioengineering as a field, because so many things, so many things are going to be done to improve our lives, whether it’s environmental issues, climate issues… biology will answer so many of those problems for us. Now that it’s progressed, it’s going to be just the largest growth sector of our economy moving forward. We have a term in Washington, we referred to it as the ‘bioeconomy,’ and it’s going to be everything from nutrition, to meat substitutes, to energy solutions, to better batteries…in addition to all the medical countermeasures, so we can live free of disease. So that’s an area that, having to do all over again, I might get involved in the biological sciences.

Articles, books, and other media discussed in the show

Andy’s photos

- Andy and President Obama

- Andy on Vozrozhdeniya Island

Andy’s writing

- Is change coming? Smartly reshaping and strengthening America’s nuclear deterrent (with Christine Parthemore)

- Mr. President, kill the new cruise missile (with William J. Perry)

- Pandemic shows need for biological readiness

- Op-Ed: COVID-19 may be teaching the world a dangerous lesson: Diseases can be ideal weapons (with Christine Parthemore)

- Cruise Control: The Logical Next Step in Nuclear Arms Control? (with Christine Parthemore)

Opportunities

- The Council on Strategic Risks’ Fellowship for Ending Bioweapons Programs.

- American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) Fellowships (Also see: American with a science PhD? Get a fast-track into AI and STEM policy by applying for the acclaimed AAAS Science & Technology Fellowship)

- Open Philanthropy’s Early-Career Funding for Global Catastrophic Biological Risks

Other links

- Emerging Tech Policy Careers — expert advice and resources on US emerging tech policy (AI, bio, etc.)

- The Dead Hand: The Untold Story of the Cold War Arms Race and its Dangerous Legacy, by David Hoffman

- Red Line: The Unraveling of Syria and America’s Race to Destroy the Most Dangerous Arsenal in the World by Joby Warrick

- How U.S. Removed Half a Ton of Uranium From Kazakhstan by David Hoffman

- Why did North Korea start the Korean War by invading South Korea in 1950?, Quora

- Was North Korea emboldened to invade South Korea partly because the U.S. hadn’t stated clearly enough that they would defend South Korea?, Quora

- U.S. Department of Defense Nuclear Posture Review Report, 2010

Dr. Tom Inglesby on careers and policies that reduce global catastrophic biological risks - Economists on FDA Reciprocity by Alex Tabarrok

- The FDA and International Reciprocity by Alex Tabarrok

Transcript

Table of Contents

- 1 Rob’s intro [00:00:00]

- 2 The interview begins [00:01:13]

- 3 Project Sapphire [00:05:57]

- 4 Georgia and Moldova [00:17:10]

- 5 How did the Nunn-Lugar program succeed? [00:23:09]

- 6 Bioweapons programs [00:29:26]

- 7 Tech that could make bioweapons obsolete [00:42:31]

- 8 Using this tech to prevent natural pandemics [00:48:01]

- 9 Chances that COVID-19 escaped from a research facility [01:01:55]

- 10 How people in U.S. defense circles think about nuclear winter [01:15:16]

- 11 Can a president unilaterally launch nuclear weapons? [01:18:24]

- 12 Top nuclear security priorities for the Biden administration [01:20:15]

- 13 Odds of a great power war between the U.S. and China [01:33:18]

- 14 Careers [01:38:59]

- 15 Rob’s outro [01:53:06]

Rob’s intro [00:00:00]

Robert Wiblin: Hi listeners, this is the 80,000 Hours Podcast, where we have unusually in-depth conversations about the world’s most pressing problems and what you can do to solve them. I’m Rob Wiblin, Head of Research at 80,000 Hours.

Today’s episode is, to my taste, our best episode on US national security yet.

We were incredibly fortunate to get to talk to Andy Weber, who for the last 35 years has been one of the most important people in the world when it comes to reducing threats coming from biological, chemical, and nuclear weapons.

Andy has always been pretty open and honest, but his retirement last year has allowed him to stop worrying about being seen to speak for the Department of Defense, or for the president of the United States – and so we were able to get his forthright views on a bunch of interesting topics, such as:

- The advances in technology that could stop bioweapons and natural pandemics

- The chances that COVID-19 escaped from a research facility

- Whether a US president can really truly launch nuclear weapons unilaterally

- And what he thinks should be the top priorities for the Biden administration

Andy has also been involved in some wild stories during his career, and he shares a few in this interview.

And one of them – about finding 600 kg of unsecured, highly enriched uranium sitting around in a barely secured facility in Kazakhstan, and eventually transporting it to the United States – is even being made into a Hollywood movie.

Alright, without further ado, here’s Andy Weber.

The interview begins [00:01:13]

Robert Wiblin: Today, I’m speaking with Andy Weber. Most of Andy’s last 35 years have been dedicated to reducing the threat from weapons of mass destruction. He played a key role in implementing the 1991 Soviet Nuclear Threat Reduction Act in the mid-90s, helping to remove 600 kg of highly enriched uranium from Kazakhstan and Georgia, among other things. This story was described in the 2010 Pulitzer Prize-winning book The Dead Hand: The Untold Story of the Cold War Arms Race and its Dangerous Legacy, by David Hoffman. Andy was later the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Nuclear, Chemical, and Biological Defense Programs from 2009 to 2014, during which time he was the principal advisor to the Secretary of Defense on Nuclear, Chemical, and Biological Defense Programs and oversaw the Defense Threat Reduction Agency, which aims to combat weapons of mass destruction. For all this work, he has twice been awarded the Exceptional Civilian Service medal. Thanks for coming on the podcast, Andy.

Andy Weber: Thank you, Rob.

Robert Wiblin: I hope that we’re going to get to talk about your experience chasing down nuclear material across the former USSR, as well as how to reduce threats from biological weapons programs, but first, what are you working on at the moment and why do you think it’s important to do?

Andy Weber: Right now I’m focused on two things: Making sure that this is the last pandemic — because we don’t have to have this again, it’s completely preventable — and reducing the threat of nuclear war.

Robert Wiblin: I was next going to ask what defense threats you’re most worried about today, but I suppose that answer speaks for itself — you’re worried about pandemics and the possibility of nuclear war, either deliberate or accidental?

Andy Weber: Well, I’m very worried about weapons of mass destruction, but especially biological weapons. I believe that the current situation has exposed a vulnerability. And actually there are two trends that are increasing the threat of biological weapons. The first is just advancements in technology, that’s making it more accessible. And then the other is, obviously this pandemic. This virus has brought our country to its knees and our adversaries are noticing the impact that biological weapons could have, even though in this case it wasn’t a weapon. Imagine if instead of 2% of infected people dying, it was 30% or 50%.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. There’s no reason why in principle that wouldn’t be possible, because we know there have been pandemics in the past that did have that kind of fatality rate, like the black death and smallpox to some extent.

Andy Weber: Exactly. Yes, smallpox had a 30% mortality rate.

Robert Wiblin: You recently tweeted that you think the Department of Defense needs to stop its emphasis on preparing to fight World War II-style traditional wars. To what degree is that still the DOD’s focus, and why do you think that’s bad?

Andy Weber: Well, unfortunately the DOD is a very conservative organisation. It’s very hard to change. It has over 3 million people. The emphasis of the Trump strategy was on big power competition, especially China and Russia, but that just gave a pretext for what Eisenhower called the ‘defense industrial complex’ — the big defense contractors to say that we need more big ships and aircraft carriers and F-35s and joint strike fighters and what I would refer to as Cold War platforms. They’re very expensive, but it’s hard to cut programs like that. They have a lot of support in Congress because of the jobs the production of these big platforms provides. It’s just very, very hard to focus on the actual defense needs of today. We’re not going to have a big land war with China. It’s absurd to think that we would, but our strategy seems to be to invest in those capabilities.

Robert Wiblin: I wanted to help people understand where the whole threat reduction community that you’re a part of is coming from, and to talk about these remarkable efforts to secure a nuclear material after the breakup of the USSR, some of which you were a part of. So what were the defense threats that you and your colleagues were most worried about in the earlier to mid-90s?

Andy Weber: Well, especially when the Soviet Union collapsed, we were very worried about the loose nuke problem. And then the stunning revelations about the scope of the Soviet offensive biological weapons program caused a lot of concern. But what changed was, we were no longer worried about the Soviet attack on the United States. We were worried about a weakness and loss of control of the weapons, the materials, and the expertise, the scientists involved in these programs, perhaps being attracted to rogue states like North Korea and Iran.

Project Sapphire [00:05:57]

Robert Wiblin: Later on I’m going to ask how it is that the whole situation didn’t blow up in our face, because it’s kind of surprising to me, but let’s go through it bit by bit. How did you end up first finding out that there were these notorious 600 kg of unsecured, highly enriched uranium sitting around in a barely secured facility in Kazakhstan?

Andy Weber: Oh, well that was a story that was told in The Dead Hand, and it’s being made into a Hollywood movie.

Robert Wiblin: Oh, really?

Andy Weber: Yes, but—

Robert Wiblin: One of my questions was going to be, “When is this going to be adapted for Netflix?” I didn’t realise it already was, effectively.

Andy Weber: Well, it’s in process. So it started when my auto mechanic asked me — he knew I worked at the embassy — he asked me one day if I was interested in buying some uranium. And at that time, after the breakup of the Soviet Union, I was recently assigned to our embassy in this new country of Kazakhstan, in the original capital of Almaty, and anything was possible, strange things were happening at that time. So I didn’t just dismiss it out of hand. And I spent several months following up on that initial lead.

Robert Wiblin: I’ve heard the saying about when your cab driver starts asking you about Bitcoin or real estate, then you know you’re in a bubble and need to get out. I suppose if your auto mechanic starts asking whether you want to buy uranium, you know you have a problem of a different sort.

Andy Weber: Yeah. And frankly, there was a lot of disbelief when I reported this back to Washington. But over time we were able to verify that indeed they had over 600 kg of 90% enriched uranium sitting at a warehouse in northeastern Kazakhstan.

Robert Wiblin: Did the U.S. end up getting scammed a bunch of times? I suppose some people noticed that it was possible to potentially get a lot of attention just by claiming that there were unsecured weapons somewhere, and then potentially someone would pay you off, just because they were so nervous about the situation. Was that a common issue?

Andy Weber: No, I mean, there were a lot of scams. The U.S. government was very careful not to become embroiled in any of these scams, which is why we worked very carefully to transition this from a black market deal over to a secret government-to-government project.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. Is it possible to lay out how dangerous the situation was with this material? What plausibly could have happened, with greater than 1% probability, not a tail risk, but a realistic scenario?

Andy Weber: Oh, well, we were concerned about Iran having an enrichment capability, which is a large industrial capability. But had they bought this material, they would have enough for several dozen bombs right away. They wouldn’t have to go through the process of enriching uranium. This was directly weapons-usable material.

Robert Wiblin: What were the main challenges that you faced getting it out? So you mentioned this suspicion from Washington, but I imagine possibly also the Kazakh Government, having been part of the USSR just very recently, might not have been so keen to work with the U.S.? And I guess there was transport, and risk from handling, and risk from it perhaps getting stolen from you on route?

Andy Weber: Yeah. There were a lot of risks. I think the biggest risk we felt was that if we lost the secrecy, then the material would become vulnerable. Especially when we have people on the ground packaging the material. We didn’t want the bad guys — whether it’s organised crime, or operatives from other countries — to know that we were loading this material, which was definitely most vulnerable when it was mobile, when it was loaded onto trucks, in preparation for the convoy to the airport.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah, so it took a long time to identify all these materials and then pack them safely, because it was all just, all kinds of different things strewn across this facility. And I guess you also have to be very careful to not let too much of it get too close, because then that can itself cause a chain reaction, and lead to a very dangerous situation. So it was several months that you spent identifying it all and figuring out how to package it safely to send it to the U.S., right?

Andy Weber: Right. So in February of 1994, we met secretly with President Nazarbayev across the street from the White House where he was staying at Blair House, and obtained his agreement to allow me and another technical expert from the U.S. weapons laboratories to secretly visit this facility in Ust-Kamenogorsk in Kazakhstan, to verify the existence of this highly enriched uranium. And when we first entered the storage room, which was protected by a good padlock, the buckets — the different stainless steel containers filled with uranium — were spread out along a very large plywood table off the floor. And they were spread out in order to avoid criticality issues, so we had… Yes, you don’t want to have too much of this material concentrated in one place.

Robert Wiblin: I’m surprised that you were able to keep it a secret, because it seems like in order to do this, you would have had dozens, possibly hundreds of people coordinating on it to some degree on the U.S. team. But then also dozens of people must have known about it in Kazakhstan, and you wouldn’t really know exactly who is trustworthy and who isn’t inside the Kazakhstani Government, and I assume there were substantial amounts of corruption, especially at that time, just after the Soviet Union had collapsed. And there’s lots of issues of people not getting paid, and so their interest in selling this material, or just walking off the job, because there wasn’t money to pay the military or the people who were meant to be securing these facilities… How did you manage to keep things under wraps so effectively?

Andy Weber: Well, I think it’d be much harder today with the internet and email et cetera, but back then it was pretty… Because both countries recognised the importance of keeping this secret, in order just to keep the operation secure, the number of people who knew about it initially was very, very small. Really only three people in the Government of Kazakhstan — including the president — were directly involved in the discussions. And then as we went operational and deployed the team, obviously the people at the factory knew what was going on. But remember they were in a formerly secret military city of the Soviet Union, so secrecy was in their culture. They knew not to talk to people.

Robert Wiblin: That’s interesting.

Andy Weber: Yeah. We were concerned that the media would learn about it. And indeed somebody in Washington on the National Security Council staff couldn’t help themselves, and talked to a New York Times reporter. And this was right before we were getting ready to fly the material to the United States. So we asked them, for national security purposes, to hold the story for a couple of days. And we said that we would give them an exclusive once the material was safely in the United States. And they agreed to do that.

Robert Wiblin: That’s very interesting. I guess one might’ve thought that the loose side would be the Kazakhstani side, because you wouldn’t be able to control them and you don’t know who’s trustworthy — but I guess the U.S. just being a more open society in a sense, and people being more willing to talk about stuff… In fact, maybe the bigger problem was on the U.S. side, even though you had this whole infrastructure of people who you thought could keep things classified.

Andy Weber: Yeah. So definitely the concern about leaks was more focused on the U.S. side, but it was extremely tightly held until we were actually getting ready for the press conference that was to be held once the operation was completed. We had simultaneous press conferences in Kazakhstan and at the Pentagon in Washington, D.C. So then the circle of people in the government at the White House grew a little bit towards the end, and that’s when it leaked.

Robert Wiblin: So to make a long story short, you ended up successfully airlifting all of it in these… Some of the largest planes in the world did maybe their longest flights ever, directly from Kazakhstan to the United States, and you had to keep it secret even after the material had landed in the U.S. Were there any problems with the operation? It seems like it was basically a complete success in the end.

Andy Weber: Yes. It was successful. There were some hurdles we had to overcome. So the C-5 Galaxy aircraft, on the flight back, were not allowed to land anywhere, they couldn’t overfly any country’s territory because of the cargo. So I believe there were four aerial refuelings en route. It was the longest flight that aircraft had ever taken, literally halfway around the planet, from Ust-Kamenogorsk, Kazakhstan to Dover Air Force Base in Delaware.

Robert Wiblin: What route did they take, I guess they went west across the Atlantic?

Andy Weber: Yeah. They went mostly over water. Over the Caspian and the Black Sea, then through the Mediterranean, over Gibraltar and then over the Atlantic. I think we called it ‘wet feet.’

Robert Wiblin: Right. Was there any worry about the possibility of the planes crashing? I don’t know how standard it is, to have them doing such long flights that they’re doing four aerial refuelings. Maybe that’s common practice, but you’d have to worry about them actually crashing somewhere, right? And then the material getting spread all over the place. So, yeah. I don’t know how dangerous the situation would be.

Andy Weber: Well, I think the riskier issue was the airfield at Ust-Kamenogorsk wasn’t really built to handle aircraft of this size. When they landed, I was on the ground to welcome the first aircraft, because we didn’t have any U.S. Air Force controllers on the ground. I was in the tower at the airport, helping guide the plane in, because nobody in the tower spoke English. And so they would tell me in Russian what to tell the pilot and I would—

Robert Wiblin: You’d just translate.

Andy Weber: —translate and talk to him directly on the radio. Watching these big planes land was really something. But they were able to land. And then the other big challenge was on departure. We were in a race against winter, and winter starts early in that part of the world, it’s just over the border from Siberia. And on the night we had the convoy from the factory to the airport, there was snow and black ice on the roads. And these trucks loaded up with the highly enriched uranium were sliding, I was in the lead vehicle with the head of security for the operation, and I was just dreading having to report to Washington via satellite telephone that one of the trucks had slid off the bridge into Irtysh River and was floating down. But luckily they know how to drive in these conditions, so we made it to the airport.

Andy Weber: And then there was another challenge with our aircraft and the ice. These C-5 Galaxies have a very high tail wing, and the de-icing equipment at the airport couldn’t reach it. And so that was a big concern. We were able to get a hook and ladder fire truck from downtown to come out to the airport and they were able to reach the tails for de-icing.

Georgia and Moldova [00:17:10]

Robert Wiblin: You also helped get uranium out of Georgia, and from what I’ve read, some nuclear-ready warheads out of Moldova? But I haven’t seen as much written about those two stories, what’s the outline of those?

Andy Weber: Georgia was sort of a mini Project Sapphire. We were very concerned, they had a research reactor that had some spent fuel, but also some highly enriched uranium in the form of fresh fuel rods that would be usable in nuclear weapons. So we were also concerned because the president of Georgia at the time, Eduard Shevardnadze, there was an assassination attempt on his life, on his motorcade. So we figured we’d better get this material out of Georgia. And so I spent about a month in Tbilisi, Georgia, with 50 U.S. Marines and a team from the Department of Energy, packaging this material and getting it ready for transport. But because of the security situation there, we spent a lot of effort making sure that the route was protected, that we had a good secure convoy with the armored personnel carriers and the like.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. Was it difficult to get permission to send U.S. security personnel into what was previously the Soviet Union? How much reluctance was there to let people like you in, or were the governments here sufficiently worried about the situation themselves that they were happy to do what it took to fix it?

Andy Weber: It’s funny, it almost seems quaint now after 20 years of forever wars, but the biggest problem was that the U.S. State Department didn’t want to allow our Marines to be armed in the country. But the commander of U.S. forces in Europe insisted that they be armed in order to protect themselves and the material. And so we worked out an agreement, and we were armed and had good security, but we worked very well with the Special Mission Unit of the Georgian Security Services. They were fantastic, and they loved working together with us.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. And what was the situation with Moldova?

Andy Weber: So Moldova, a country the size of Rhode Island, had inherited upon the breakup of the Soviet Union a fleet of MiG-29 aircraft, but they were the Soviet domestic version, not the Warsaw Pact version that countries like Poland and East Germany had. And they were nuclear capable, they were wired for nuclear weapons. And we were very concerned because Iran was trying to buy them. Of course, a country the size of Rhode Island had no need for these advanced fighter jets. And the government said to us, “What are we supposed to do with these aircraft?”

Andy Weber: We were very interested in obtaining them, first of all to preempt Iran’s acquisition, but also because of the technology that was on those aircraft. And so we negotiated a secret deal with the Government of Moldova to buy all of them. We bought 21 MiG-29 aircraft and 507 air-to-air missiles and all the spare parts and all the documentation. And we moved them to the United States in a secret airlift that lasted nearly three weeks.

Robert Wiblin: I’m surprised that some of these countries didn’t put up more of a fight maybe to keep these materials, because we’ve seen lately that Ukraine has suffered from ultimately deciding to give up its nuclear weapons. I mean, it was given security guarantees, but those haven’t panned out. Did any of these former Soviet States seriously consider, “Well, why don’t we just keep all of these weapons? That could be potentially useful in future in some situations that we hope don’t get envisaged.”

Andy Weber: Well, besides Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Ukraine had large numbers of nuclear weapons on their territory when they became independent. And I think of the three, Ukraine was the most difficult — they did seriously consider hanging on to them. And so it was diplomacy combined with the resources of the Nunn-Lugar Cooperative Threat Reduction Program that allowed us to negotiate with Ukraine to give up those weapons and allow them to be sent to Russia.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. How did you feel seeing Crimea being annexed from Ukraine, knowing that there was this long discussion in the 90s about people trying to guarantee Ukraine that it would be secure, even if it gave up its nuclear weapons, and that not panning out after a couple of decades?

Andy Weber: Well, it was outrageous. I mean, we hadn’t seen anything like that kind of territorial grab since World War II in Europe. So it was outrageous, but we also saw the attack on Georgia in 2008, so Russia can lash out in a very aggressive way.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. We’ll come back to issues with Russia today later on. These were a handful of operations in what was a much larger project. How much material and how much risky people and risky uranium and other weapons were ultimately secured across the former USSR, using methods like this?

Andy Weber: Most of it was either destroyed or secured in place. This was a decades-long effort, funded mostly by the U.S. Department of Defense, to help them destroy these materials and missiles, and also to build secure facilities to make sure that the material would be protected. So this went on… But the amount of materials that were secured and weapons that were destroyed, including chemical weapons, nuclear weapons dismantled, SSE team missiles cut up, it was just in the thousands. It was an amazing effort to help our former adversary eliminate the legacy of the Soviet Union.

How did the Nunn-Lugar program succeed? [00:23:09]

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. This brings me to maybe the biggest question I have about this whole program, which is, why was it so successful? I can’t comprehend how more of these materials didn’t end up in the hands of terrorist groups or rogue states, because there was just so much of it across so many different locations. As you said, it took decades in fact, to secure it all, because there was so much work to do, moving it, destroying it, securing it. And I’m just so confused, is it possible that some of it did get out and was sold, we just haven’t seen it yet? Or maybe not as many people were interested in buying this material as we thought at the time?

Andy Weber: Well, this is a prevention program, right? And so you don’t get credit for the catastrophe that didn’t happen, but it is an extraordinary story. I mean, it was the vision of Senators Richard Lugar and Sam Nunn that created this program, gave it to the Pentagon to run, and then at first the Pentagon was a little reluctant to be involved in working with Russia on this problem. But the reason it was so successful, indeed, the genius of this program, was that it facilitated work directly with the custodians of these weapons and materials.

Andy Weber: There were some negotiations in the capital with the foreign ministry, but for the most part, we worked in very remote locations at these WMD facilities and bases throughout Russia and the neighboring countries, directly with the engineers and the security forces who guarded them and the people who felt a responsibility to protect them. So that was the genius, and that’s why we were so successful, because it was a full partnership with our counterparts in those countries.

Robert Wiblin: So is it correct that basically you guys succeeded every time, and I suppose Iran and Al-Qaeda failed in every instance to buy this material? It suggests maybe that the custodians were just not in fact interested in selling it to those groups, that they saw that that was extremely dangerous and could blow back on them, or maybe they were just against it getting out to anyone who would actually want to use it.

Andy Weber: Well, they were desperate in the 90s, the economic distress was grave, but we offered an alternative. One example is that we worked with the laboratory in Siberia called VECTOR that developed smallpox, Ebola, and Marburg virus as biological weapons, and the Iranians were targeting that facility for the pathogens themselves, for some of the technologies they developed, to produce them and weaponise them. And also were inviting scientists to come teach courses in Tehran. So we offered an alternative: You can work with the United States, European scientists, on peaceful point research on new vaccines and therapeutics for infectious disease. Or you can continue your engagement with Iran, but you need to make a choice. And given that choice, and the financial support we were able to provide, they wanted to work with us.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. I guess you were more credible and you bid higher, among other things. And I guess also they probably just preferred you ideologically, even despite perhaps some differences.

Andy Weber: Yeah. There was a lot of respect. We had been adversaries so long that they had a real respect for us, and many of them had spent their lives in these secret cities. They’d never met Americans obviously, or any foreigners. And they were curious about us, intrigued by us, and at the end of the day, there was that respect that comes from working on these very dangerous programs, and between scientists there was a common language that we were able to reach.

Robert Wiblin: What about the program to secure people with dangerous knowledge? I know after World War II there was a huge effort from the U.S. and also the USSR to try to get as many German scientists, nuclear scientists, and weapons scientists to join them as quickly as possible. Was there a similar project to get as many Soviet physicists to move to the U.S., so that they couldn’t potentially end up working on programs that you wouldn’t want them to?

Andy Weber: Well, there were some programs to facilitate immigration to the United States and Europe, but for the most part, the strategy was to provide support so they could live with dignity and stay in their homes in their own country and their own towns. And so the emphasis was really on making it possible for them to continue to get paid doing peaceful work and not weapons work, or even dismantling weapons. Another profound example for me was the anthrax factory in Stepnogorsk, Kazakhstan. It was the world’s largest biological weapons factory. You can’t imagine the scale, it was built to produce…to load onto weapons aimed at the United States, 300 metric tons of anthrax agent in about an eight-month mobilisation period.

Andy Weber: But the people who built this horrible, really evil factory, in violation of the biological weapons convention, they worked with us, they actually did the dismantlement. Their engineers and scientists ensured that it was done safely, but they did it on direct contract with the Department of Defense of the United States. Indeed, it became their livelihood. When they finished safely destroying the main fermentation building, they said, “Well, can we also dismantle this other building?” So it generated a momentum of its own, it was really extraordinary. They had some regret, obviously, they had great pride in having built and operated this facility, but because of the economic situation, and once they learned that this program was illegal, that the United States didn’t have a similar program, then they came around and put those same energies and talents to destroying these weapons of mass destruction.

Bioweapons programs [00:29:26]

Robert Wiblin: Speaking of bioweapons, let’s move on from efforts to secure Soviet material back in the ’90s and 2000s to the present day. Because one thing we haven’t talked about much on the show before in the 90 or 100 episodes that we’ve had is bioweapons programs, even though they are quite concerning. What is the nature of the threat from bioweapons programs?

Andy Weber: Bioweapons — developed during the Cold War by the United States until Nixon canceled our program in 1969, and then the Soviet Union right up until the collapse — were potentially equally devastating to nuclear weapons. They were called the ‘poor man’s atomic bomb.’ It’s easier for a country to develop biological weapons than it is to develop nuclear weapons — it’s essentially the use of infectious disease as a weapon. And this could be devastating. There are different types of diseases with different effects, but the ability to deliver them against a population or on a battlefield or to an individual makes them really an insidious type of weapon.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. How large was the threat in the ’80s and ’90s?

Andy Weber: In the ’80s and ’90s, the primary threat came from the Soviet Union. They grew their program, and when the ink was drying in 1975 on the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention, that’s when they upped their investment in this program, knowing that the United States no longer had one. They sought an advantage. At one point they had about 50 or 60 facilities working on their biological weapons program, 40,000 or 50,000 scientists and engineers. It was a massive, massive effort, and thankfully they never used them.

Robert Wiblin: And yeah, how large is the threat today, do you think?

Andy Weber: The threat is different today, but it’s probably greater. And I say that because the technology has advanced, and the Soviet program applied sort of rudimentary molecular biology in ways to make viruses and bacteria more effective as weapons. But now the tools are much easier to use, more precise. So you can enhance the virulence, the transmissibility, the environmental hardiness of pathogens in a way that just wasn’t possible back then. So I’m very, very concerned today that especially North Korea — which we know a lot about their missile and nuclear weapons programs, they have an advanced biological weapons program. I’m concerned that Russia still continues elements of its biological weapons program. It’s on a much smaller scale, but you don’t need a lot of biological weapons to kill potentially billions of people.

Robert Wiblin: I know bits and pieces of the history of the Soviet biological weapons program, but maybe I’ll say those and then you can perhaps fill in some gaps. As I understand it, in the Cold War, the U.S. and the USSR both had pretty substantial biological weapons programs. And then you were saying in the ’70s, they signed an agreement to close them down. And the U.S., interestingly enough, did close them down. I think the Soviets thought that the U.S. probably would continue doing it secretly, but in fact, Nixon and maybe others did just decide to shut down the biological weapons program. And maybe they weren’t sure what the USSR was doing.

Robert Wiblin: But the USSR continued — and in fact scaled up — its biological weapons program. And if I recall correctly, was it Gorbachev who said that allowing the biological weapons program to continue was his greatest regret, or the worst thing that he ever did? But I think the military threatened to basically overthrow him if he got rid of the biological weapons program, or either way, there was a lot of political power that that group had, which made them hard to shut down. Is that kind of a good outline?

Andy Weber: Yeah. The Soviet biological weapons program was the greatest Western intelligence failure of the Cold War. We missed it. It wasn’t really until the first defector came out to the United Kingdom in 1989 that we began to learn about the scope and sophistication of their illegal bioweapons programs.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. It’s kind of surprising, you were saying they had tens of thousands of people working on this program, and yet it never leaked. It’s just an incredibly effective secrecy.

Andy Weber: Yeah. It was extraordinary. It was like an onion, right? Different layers. Some were indirectly involved in their bioweapons program — for example the ‘anti-plague system,’ which collected pathogens from fleas and rodents. But then the most virulent ones were selected and then sent into the biological weapons research and development facilities. So you have layers and layers, but at its core, it was a military program, a strategic program intended to be used as a strategic weapon against the United States and NATO.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. How much has been successfully done to get rid of these kinds of programs, or at least shrink what they’re up to, if a country wasn’t willing to give them up completely? Who’s still at it today? Other than, I guess you mentioned there’s some research in Russia, and North Korea probably has a decent program.

Andy Weber: Yeah. North Korea has an advanced biological weapons program. What worries me about North Korea is they’re more likely to use biological weapons than nuclear weapons, because if they used a nuclear weapon, it’s over, right? If they used a biological weapon and delivered it covertly through secret operatives, anywhere in the world… In Malaysia, where they used VX against a Kim Jong-un’s brother in a successful assassination attempt. Now that was a chemical weapon, but wherever North Koreans have a diplomatic presence, they could launch biological weapons attacks covertly. And in a way, perhaps that’s a little bit deniable, maybe they would never get caught for doing it. So I think they’re more likely to do that than to use a nuclear weapon, which would have a home address.

Robert Wiblin: Is there anyone else we need to have in mind? Who else actually has programs at the moment?

Andy Weber: Well North Korea, and our concerns about Russia continue. There were three military biological facilities [in Russia] that we were never allowed to visit, and we are concerned that they’re still working on biological weapons today. Indeed just last year, they were sanctioned by the U.S. government. But we also have some concerns about China, and I’m concerned that because of the success of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, that countries that hadn’t considered biological weapons will now be thinking about them.

Robert Wiblin: Okay. Yeah. So I think a core question that people might have is just why would a country want to have a biological weapons program, perhaps except for North Korea, as a deterrent? It seems like it’s kind of crazy. Because as we’ve seen with COVID, if you release a disease anywhere, it kind of ends up everywhere. And so if the Soviet Union had ever actually used most of these biological weapons — at least the ones that are contagious, which are naturally the ones that we’re most concerned about — then it’s just going to end up decimating their own population. Perhaps at a delay of weeks or months, but it seems like it’s kind of a ‘mutually assured destruction’ thing. And I guess on top of that with the Soviet Union, they already had all the nukes. They already had a very strong deterrence against being attacked. So it’s just very hard to see, like what is the strategic position that biological weapons play in defending a country.

Andy Weber: Well for a country that has nuclear weapons, it really is madness to also develop biological weapons. But for a country that can’t afford the investment into nuclear weapons, biological weapons offer a shortcut — a cheap, easy way to do it, and in a way that’s deniable. And the example of Iraq is interesting. They did have a pretty good biological weapons program in the early ’90s. And then when we went in, in 1991, we disrupted it and the UN shut it down. It was completely eliminated by 1996. But they didn’t have a nuclear weapon. So they wanted their neighboring countries to think that they had a biological weapons program. They hinted at it. They had that ambiguity and they thought that was a deterrent.

Robert Wiblin: Given that, why haven’t more countries developed biological weapons programs? I guess a country like Iran might be kind of a candidate that would be interested in the same way that North Korea is.

Andy Weber: Well, the world has been lucky. We have the Biological Weapons Convention. We do try to shine sunlight as a disinfectant on the covert programs that we learn about. But it’s a success. It’s a global success that the norm against biological weapons has generally been effective, and more countries are not pursuing them.

Robert Wiblin: Why did the Soviet Union keep its program, given that it was kind of a threat to the country itself? Because they could accidentally get out, and it wasn’t really playing any strategic role in preventing the Soviet Union from being invaded. Was it just some kind of peculiar internal politics where some people were getting jobs that they liked out of it, or was there misunderstanding?

Andy Weber: Well, no, they definitely saw military utility in it. And there are different kinds of biological weapons — ranging from incapacitating agents that just make everybody sick and unable to fight on a battlefield, to non-contagious biological weapons like anthrax, which does not spread human to human. So you could launch a large-scale anthrax attack on a city and kill hundreds of thousands of people without risking any blowback on your population. And then the distances. I think they felt that if they used bombers or intercontinental ballistic missiles to deliver biological weapons against the United States, then it wouldn’t work its way back to the Soviet Union.

Robert Wiblin: Okay. So they would be able to cut it off at the borders and it wouldn’t necessarily come back. Was that a foolish belief?

Andy Weber: Well, we weren’t as interconnected back then, right? The air travel and the communications links were not as well developed in the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s as they are today. I think today, use of a contagious biological weapon anywhere in the world would risk spreading everywhere, as we’ve seen with COVID-19. But that doesn’t mean that having a highly contagious biological weapon in your inventory isn’t something that countries wouldn’t want to have, even given that risk.

Robert Wiblin: Just because it terrifies everyone else?

Andy Weber: Exactly.

Robert Wiblin: I see. So it just makes them really nervous to irritate you, because they don’t know what you’re going to do, or they don’t know what might happen if your country collapses, or if the government changes? Because then the weapons could fall into the wrong hands and so they just leave you alone.

Andy Weber: Yep.

Robert Wiblin: Interesting. So given that countries — even including North Korea — probably wouldn’t want to use these weapons, except in very peculiar circumstances, is the most likely way for them to end up doing a lot of damage just them being released accidentally perhaps? Or say there’s a war, or destabilisation for some other reason, and then they get out?

Andy Weber: Well, there have been accidental releases. In 1979 in what’s now Yekaterinburg, Russia (it was called Sverdlovsk at the time), at one of those three military biological weapons facilities that I mentioned one of the workers didn’t replace the filter correctly. And a significant amount of anthrax was released into the city. And well over a hundred people were killed in that instance. So accidents do happen.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. Why would a country want to use anthrax when they could just use a chemical weapon? Is it just that it’s fatal with various…like it can kill a lot of people with a relatively tiny amount of the substance?

Andy Weber: Right. So chemical weapons are bulky and they act immediately. But the amount of chemical weapons that you would have to deliver to kill a million people, it’s unwieldy, whereas 1 kg of anthrax would do that for you. If it’s dispersed in an aerosol in a densely populated area, you only have to get a little bit into your lungs to get infected. And so if there are millions of spores released into the atmosphere, that can kill just an extraordinary number of people.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah, okay. That makes sense. I guess maybe this is a silly question, but given all of this, why did the U.S. actually follow its agreement and dismantle its biological weapons program? Was it a matter of honor, or did the U.S. see less of a strategic role for biological weapons in defending its interests?

Andy Weber: Yeah. I’ve actually talked to some of the people who are now in their 90s who were involved in those decisions in 1969, when President Nixon got rid of the U.S. biological weapons program. It was a combination of things, but mostly it was a concern that biological weapons would spread to other countries, that more countries would pursue them. And we thought that if we signed a convention prohibiting them — and then get all the countries of the world to join in that — that it would make it less likely that countries would pursue biological weapons. And indeed, that was generally effective, with one huge exception of the Soviet Union’s flagrant violation.

Tech that could make bioweapons obsolete [00:42:31]

Robert Wiblin: Is there any case for not worrying that much about bioweapons? They sound pretty bad, but is there anything you can say that maybe makes the picture seem a bit less scary?

Andy Weber: Yeah, maybe it doesn’t come through, but I’m an optimist by nature, sort of a pragmatic optimist. And I think we can take the whole class of biological weapons off the table. And we’re doing work on this at the Council on Strategic Risks. We have a program called Making Bioweapons Obsolete. At the end of the day, biological weapons are just infectious disease, right? So you can have a system of early warning detection and then rapid medical countermeasures that would give you such good defenses against biological weapons that you could deter your adversaries from pursuing them, because they would realise they wouldn’t be effective. And we’re not there yet, but the science and the tools that are now available can enable this possibility of making bioweapons obsolete. And so we think that’s the right vision.

Robert Wiblin: Okay. Yeah, fantastic. I’m super curious, can you maybe just go through some of the technologies that you’re most excited about, that could potentially make bioweapons obsolete?

Andy Weber: Absolutely. So it starts with early warning. So think about some of the revolution in diagnostics and testing that’s been happening because of COVID. So imagine in-home testing, every morning when you’re brushing your teeth, you breathe into a tube and you know if you’re infected with a virus and it tells you which one. That’s sort of the early detection that’s now possible. You might have it hooked up to your smartphone and it would report into a public health surveillance system. And so you would know if it’s just an isolated individual or if it’s spreading into the community.

Andy Weber: So that early warning piece. And then sequencing is becoming so cheap and fast that within 24 hours, you can determine if a person has a respiratory illness, for example. You can test through sequencing for 300 different pathogens, as well as virus X, the unknown, the novel. And those are the sorts of capabilities that we need in order to have that weather map, that prediction of infectious disease outbreaks that allows us to nip them in the bud.

Robert Wiblin: So I know that sequencing technology has gotten a lot cheaper, and I’ve heard people talk about at every hospital or medical facility, you could have one of these little nanopore sequencers, and then you can take lots of samples and see if you’re getting DNA results or sequence results that you don’t recognise. And that would set off alarm bells because it’s like, “Oh, this is something new. We need to look into it.” How would you do this at home? You’re saying you would blow into something at home and this will be cheap enough and it would be able to tell all the viruses that you had going around in your respiratory tract? That’s amazing.

Andy Weber: Right. So those capabilities that you’re talking about, that a hospital laboratory might have today, they’re getting smaller, cheaper, and easier to use. So it’s just a matter of time before they’re available for use at home. But we also have many in-home tests already for COVID, that are now approved for emergency use by the FDA. Even just in the last few months, there have been some new ones that are being purchased by the government. We have a several hundred million dollar contract with an Australian company called Ellume that produces an in-home test. So I think there’s also a demand for it, right? You want to know before you send your child off to daycare that he or she is healthy.

Robert Wiblin: I guess maybe even more than that, you want to know what the other kids at the daycare have.

Andy Weber: Exactly, right. And the teachers want to know that too. So this type of monitoring and screening is possible today. But what we need to do is invest more in it, and then connect it into a system so it’s not just fragmented information being collected, that we get the overall weather map, the total picture for infectious disease everywhere in the world. And real-time information sharing is going to be key to that.

Robert Wiblin: Is a potential weakness here that if someone really wants to do a lot of damage, couldn’t they release these diseases into very poor places in the world, where this technology is not going to be in every household anytime soon? And then they could spread a whole lot before they got to rich enough countries where they might be contained, but then they would still do a lot of damage.

Andy Weber: That’s why we need to invest in these capabilities everywhere in the world, because an outbreak anywhere is a threat to the whole world. So that’s why in 2014, the United States led a huge diplomatic effort to create what was called the Global Health Security Agenda, which has now grown to include over 70 countries and international organisations, to enhance the capabilities of every involved country to detect and respond to infectious disease outbreaks.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. I guess even if you can’t predict every country, it would still mean that the number of use cases for countries actually applying these weapons would be much smaller because they wouldn’t be able to do a targeted attack on one particular country, if that country had these defensive capabilities.

Andy Weber: Yeah. And actually, day-to-day, the poor countries need these capabilities even more because they’re suffering day-to-day from more infectious disease than we do in the West.

Using this tech to prevent natural pandemics [00:48:01]

Robert Wiblin: A side benefit, if you can call it that, of this kind of technology, if it was scaled up everywhere, is that it’s the kind of thing that would have caught COVID-19 early enough to perhaps contain it. Actually, while we’re on that, if we had this technology that could stop bioweapons, I guess that would actually basically be good enough to stop natural pandemics as well, because if anything, the bioweapons are going to be more difficult to contain because they’ve been designed for that purpose? Whereas the natural ones, it’s only by accident that they happen.

Andy Weber: That’s exactly right and that’s why making this investment now is so important and so beneficial. Not only would it protect us from biological weapons threats, it would protect us from routine infectious disease and prevent pandemics and epidemics from happening in the first place.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. And so that was the early detection, which is kind of, I guess, sequencing initially at hospitals and labs and spreading it out. And then I guess eventually, the dream would be in every home every day. What are the later stages? What are some other technologies?

Andy Weber: Well again, enabled by sequencing, look at the example of how a Chinese laboratory posted the SARS-CoV-2 sequence I believe on January 11th, and within days, a DARPA-supported company in Boston called Moderna developed this mRNA vaccine prototype. And then it was in phase I trials, just a little over a month later. So using sequences, we can have what I call rapid medical countermeasures — therapeutics and vaccines that are based on the sequence of the pathogen and can be developed and then manufactured quickly. Think sort of nucleic acid 3D printers that could use this digital information — because biology is now digital — and develop and produce these vaccines in a distributed way. So we would, as soon as even a novel or previously unknown pathogen were released, we would in days — or a month at the most — have a countermeasure we can apply to preventing it. So these are the capabilities that while even 10 or 15 years ago may have seemed like science fiction, today they’re upon us. But we need to invest in this overall system of defenses.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. Just to explain to people there, I guess it seems like in the past, most vaccines have had this kind of boutique element where you have to manufacture them, it’s quite cumbersome and you test whether they work and then actually scaling up to be able to produce any specific vaccine is really hard. And I guess a benefit of mRNA vaccines, as I understand it, is that you can very quickly go from the RNA or DNA sequence of the pathogen to, I guess you take that and you do some work on the computer quite quickly, and then you’re like, “Alright, we already have mRNA vaccines, here’s the code that we’re going to put into the mRNA vaccine. Here’s the code that we’re going to put inside these little fat droplets that then is going to cause your own body to produce these proteins that will then inspire the appropriate immune response.” And so I guess you can go much faster, potentially, from discovering a new thing to having a vaccine against it.

Andy Weber: Yeah. This time it was 10 months because we have never really fully proven them in humans before, going all the way through phase III trials like we have now. But next time it will be much faster. And linking back to the Soviet biological weapons program, there’s a reason the Department of Defense invested in a capability like the mRNA vaccines. It’s simple, we knew the Soviet Union had been applying bioengineering to its weapons program. So that meant we couldn’t just worry about a list of known pathogens. It meant we had to worry about a created pathogen, perhaps a chimera — a hybrid pathogen that had the worst properties of several viruses combined. So that meant that we might face a total unknown. And so we needed a capability to sequence it, to characterise it, and then develop the countermeasure. And it’s exactly that reason that the Department of Defense invested in what we call these ‘rapid response’ or ‘platform’ technologies.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. That’s fantastic. Recently, I’ve been saying that as far as I can see, we just want to have an enormous vaccine manufacturing capacity on standby at all times, for mRNA vaccines and I guess other methods as well. It’s obvious even now just with COVID-19 because we could have new variants that are thrown up that are able to evade the vaccines that we have already, that people have already received, in which case we’re going to have to go back and create a new variant vaccine to tackle that variant of COVID.

Robert Wiblin: And then we want to be able to vaccinate everyone again with the new variant as quickly as possible, ideally within months, if it were possible. Which then means a lot more vaccine manufacturing capacity, both for mRNA vaccines and others and I guess a lot of logistical capacity to deliver them if necessary. And I guess the same is going to be true for other new diseases. And if we want to have this ability to quickly disable any new bioweapon, we need to not only be able to invent the vaccine — it sounds like possibly within days — but then also very quickly manufacture a lot of it, and then deliver it into arms on a very accelerated timeline.

Andy Weber: That’s absolutely right. And technology is helping us with that too. You no longer have to build a massive vaccine plant to produce vaccines. Again, think about 3D printers. It’s called cell-free manufacturing. There’s a company I’m aware of that is building something about the size of a glove box that can produce, for example, millions of doses of mRNA vaccine in days. Because as you said, it’s actually your body that does the production of the mRNA vaccine. It’s just the message to your cells to produce it that you’re injecting. And then for example, there’s microneedle patches, vaccine patches that could be mailed to people, right? So that would make the logistics of vaccinating people much, much easier if you can just apply a patch to your arm. New methods to eliminate the need for a cold chain, for low temperature freezers. All of these are technical challenges that we need to work on, but none of them are insurmountable.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. The bottom line for me when I was thinking about this recently was just that you might worry that perhaps we would spend too much on vaccine manufacturing or delivery, that maybe we would build up an excess capacity perhaps because we’re in this emergency situation and it would be more than we need. And then say there aren’t any new COVID-19 variants and we don’t need to create follow-up vaccines. And so we kind of wasted some money. Firstly, I think just given the size of the problem, we should be willing to scale up all of this stuff just on the possibility that we might need to do a second round of vaccinations. But also, even if we don’t use it for COVID, we really want to have this on standby definitely for future pandemics, so we never have to live through this again. I have no concern that any country is going to spend too much money on vaccine platforms or vaccine manufacturing or vaccine delivery infrastructure. It’s just really, on the margin, the more, the better.

Andy Weber: You’re right. Compare the investment we’re talking about with the costs of this pandemic and it’s a no-brainer. It really is an ounce of prevention. So we’re now using the term ‘the bio-defense industrial base’ in the United States. We need that warm base, but it’s multi-use right? During a non-pandemic time, it can be used to produce all sorts of things. But then it needs to have the agility to shift quickly to snuff out a pandemic before it becomes one.

Robert Wiblin: The political challenge here is that people have been saying for decades that we need to stockpile more masks, we need to have more vaccine manufacturing capacity on standby. We need to be doing all of these things to prepare for a pandemic when it arrives. I was able to figure this out when I was 18. I was saying we need to stockpile more masks, because Australia, where I was living, doesn’t have enough masks. If I could figure it out when I was 18, I feel like the government should be able to figure it out with all of their analysts. But the challenge then is how do you get politicians and the public to vote to spend this money, given that if you haven’t had a pandemic lately, it’s going to seem like it’s being wasted? The challenge here kind of seems like more a political economy question or a public choice question than one of figuring out whether it’s sensible to do, because it just so clearly is.

Andy Weber: Yeah. The simple fact is that it needs to be a priority. And we’re not talking about huge numbers. I think the United States, if we invested through the Department of Defense and Department of Health and Human Services about $20 billion a year in this — which when you think about it, the defense budget is currently $750 billion a year, it’s actually a pittance in DOD terms — I think we could solve this problem over about a decade. So it’s an investment that is worth making for our defense, but also for our health. Imagine a world where you don’t get colds. That’s what we’re talking about too. So it would improve day-to-day lives of people. And that’s the beauty of this, it’s a win-win-win investment.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. I wonder whether that’s one way that you could make this work commercially, is that you have this enormous capacity for manufacturing mRNA vaccines against all of the new cold variants to keep colds under control. And then of course at the drop of a hat, all of that infrastructure can then be converted to producing vaccines against a new, much more severe pandemic if necessary. But the cold vaccines are a business model that helps to support all of that infrastructure in the meantime.

Andy Weber: That’s just right. You have to have a portfolio approach, but it needs to be kept warm and used day-to-day for a routine infectious disease like the common cold. Think about what people spend on over-the-counter drugs to treat the symptoms of the common cold. So if there were something that was cheap and easy — vaccine patches or whatever that you could use to prevent colds — I think it would be very popular. So we do need to look at the private sector as perhaps the driver and sustainer of a lot of this effort. But the catalyst has to be governments. I think governments have to make this a priority, but there is plenty of innovation that’s happening today in the private sector and in academic laboratories around the world.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. I have massive respect for Pfizer and Moderna figuring out how to produce so many doses of this new kind of vaccine so quickly. It’s really impressive, but they can’t do this on their own. They don’t have the scale that the U.S. government has. And as you’re saying, it seems like this is a situation where the U.S. government invests $10 billion and then gets $1 trillion worth of saved economic activity out of it, because they haven’t had to shut everything down.

Andy Weber: It’s an investment we can’t afford not to make. It’s cheap, but we haven’t done it. You’re right. You’ve known about it since you were a teenager. I’ve been working on this problem now for over 30 years. But it’s time that we take this threat seriously, make it a national security imperative, not just something that the global health community deals with, and give it the resources that we give to other issues like missile defense, for example, which is a much less likely threat.