The payoff and probability of obtaining venture capital

Venture capital has facilitated the growth of many companies including Apple, Google and Facebook. But do most startups succeed after they obtain venture capital? In this post, we answer three component questions:

- What are the likely outcomes for companies backed by venture capital?

What fraction of companies attract venture capital?

How much work is it to apply for venture capital?

We found that:

- According to the data of Professors Hall and Woodward, the average venture capital-backed founder exits with $5.8 million of equity.

Roughly 1% of companies that aspire to obtain venture capital obtain it.

Finding out whether you will receive venture capital can take months to years of work.

What are the likely outcomes for companies backed by venture capital?

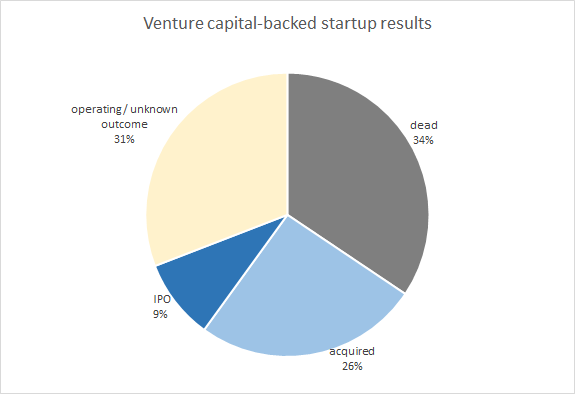

For companies backed by venture capital, failure and acquisition are more common than IPO. In 2008, Professors Hall and Woodward presented data on companies that received venture capital in the preceding two decades. In their set of 22,004 companies:1

- 9% reached IPO. At IPO, the average founder had an equity stake of $40 million.2

26% were acquired.

34% died or were taken to have ceased operations due to going unfunded for over five years. Their founders have earned only their salaries.

31% had unknown outcomes. Most of these are probably still operating. So far, their founders have only earned their salaries, although a few may go on to achieve a big exit.

Figure 1: Venture capital-backed startup outcomes. The dataset is comprised of 22,004 companies that received venture capital from 1987 to 2008. The companies were analysed at the end of that period. Companies that have gone without funding for more than 5 years are considered dead. “Operating/unknown outcome” is a catch all category for companies without known exits. Data is from Hall and Woodward’s The Burden of the Nondiversifiable Risk of Entrepreneurship.

Professors Hall and Woodward used this data to model the earnings of entrepreneurs. They found that a successful exit for the founders is even less likely than it would appear. Although 35% of companies reached IPO or were acquired, they estimate that 75% of founders have received zero income from their equity stakes. This is because in their model, some acquisitions are so small they leave no money for the founders.3 The remaining 25%, however, received a highly valuable equity stake. Hall and Woodward estimate that the mean entrepreneur exited with $5.8 million of equity.4 Although the assumptions of their model are open to debate, the overall finding that most venture capital-backed startups fail is supported by the data.

So IPOs are rare, but when they happen, they can lead to very high earnings, and this makes the average earnings of venture capital-backed startup founders very high. This earning distribution resembles our findings of the earnings of Y Combinator founders.

What fraction of companies get venture capital?

So now that we know that getting venture capital is very valuable on average, the natural follow-up question is what fraction of companies get venture capital. We take two approaches to this question:

- We estimate the number of startups and the number of venture capital deals

We note how many applicants venture capitalists say they accept

Approach 1. How many startups and VC deals are there?

In this approach, we estimate the number of new US companies, then note how many companies get their first venture capital deal each year.

How many new US companies are there?

We present three estimates for the number of new US companies: i) new nonemployer companies, ii) new nascent companies iii) newly self-employed.

For background, in the US, there are:

I: New nonemployer companies

- Estimate: 8 million nonemployer companies are born each year

Method: There are 800,000 new employers each year. Non-employer companies are more than triple as numerous as numerous as employer companies and additionally, their birth rate is over twice as high as nonemployer companies.8

II: New nascent companies

- Estimate: There are over 1 million new nascent companies each year

Method: There are now 221 million working-aged Americans. The PSED II found that 6% of working-aged Americans are creating a company, and do so with an average team size of 1.7, making 8 million nascent companies. 27% exit the nascent company category each year (either by starting to attract revenue, or by being abandoned). If there are 27% new nascent companies each year, then there are 1 million new nascent companies annually. (Discussed further in Appendix 1)

III: Newly self-employed

- Estimate: Over 1.4 million Americans between the ages of 25 and 55 become self-employed each year.

Method: There are 100.6 million workers aged 25-55. 90.03% of them are salaried. Each year, 1.4% of salaried workers become self-employed. So there are over 1.3 million newly self-employed each year.9

Combined estimate:

- Estimate: 2-10 million new companies are created each year.

Method: These three estimates are rough and partially overlap, so we give a wide confidence interval.

How many of the new companies want venture capital?

Most new companies do not aspire to obtain venture capital. They are corner shops, restaurants, hair stylists and so on. Some researchers have estimated the proportion of new companies that aspire to obtain venture capital:

- 2-4% of small employers were candidates for venture capital in the 1990s, according to analysis by Ou and Haynes

6% of nascent companies expected their operations to have large scope five years after the company’s birth, according to the PSED II

Overall, we estimate that 2-6% of new US companies are ‘startups’. (This is discussed further in Appendix 2)

How many new startups arise each year?

If there are 2-10 million new companies annually, and 2-6% of them aspire to obtain venture capital, then there are 40,000-600,000 new ‘startups’ annually.

How many venture capital deals are there?

1,350 companies get their first venture capital deal each year.10

What proportion of new companies that want venture capital will get it?

If each year, 1,350 companies get their first venture capital deal, and 40-600,000 new companies are founded and aspire to obtain venture capital, then 0.2-4% of those companies will eventually obtain it.

Approach 2. What proportion of applicants to venture capitalists say they accept?

We can make an alternative estimate by reading how many applicants venture capitalists say they accept:

- David Hornik reports that he funds 0.125%-0.4% of companies whose applications he reads.11

An employee of Pentech reports that they accept 0.6 – 0.9%.12

David Rose reports that 0.25% of companies are accepted.13

The venture capital yearbook reports that venture capitalists accept 1% of applications.14

This suggests that each venture capital company accepts about 0.1-1% of applications. By applying to multiple venture capitalists, multiple times, companies can make their chance higher than this. This is broadly consistent with the estimate that 0.2-4% of new companies that aspire for venture capital eventually obtain it.

Overall estimate and caveats:

Overall, our best guess is that around 1% of new companies that aspire to obtain venture capital eventually get it. However, there are some caveats:

The chances of any particular startup obtaining venture capital will depend on the level of maturity of the company. When a company is very young or in the creation process but not yet operating, the chances of obtaining venture capital are much lower than when a company has revenue and employees.

The chances of a startup succeeding will depend on other characteristics, like the product, team and quality of application. For example, graduates of accelerator programs seem to have much better chances – 59% of them receive follow-on funding within 12 months, although though not always from venture capitalists.15

Some companies do not need venture capital to succeed, because they are bootstrapped by the owner’s personal wealth, by angel investment, or by borrowing. Furthermore, some companies earn enough revenue that they do not require external investment.

How much work is it to apply for venture capital?

The chance of venture capital is low, while the average payoff is high. So a reasonable question to ask is: “how long will it take to find out whether I can get venture capital?”

Many business activities must be performed before a venture capital application will be taken seriously. To get funded, you usually need to to show that you have a talented team, a prototype and traction.16 The chance of success may be greater and the preparation time less if you are personally connected with venture capitalists.17 If one is not personally connected to venture capitalists, it is still important to research venture capitalists before applying; many applications are thrown out because they do not fit the fund’s market area policies.18

Another way of considering when companies tend to receive venture capital is looking at the stage of first-time venture capital deals. PWC reports that of 1,350 occasions where a company receives their first venture capital, 225 are given in the seed or startup stage.19 CB Insights gives a higher figure of 843.20 This means that at least one third of startups that eventually receive venture capital startups use alternative means of funding to progress through the seed and startup stages. So seed funding can include angel investors and incubators. This means that many companies have to operate for years before obtaining venture capital.

Overall, for founders who are not personally connected with venture capitalists, months to years of work are usually required before funding as obtained.

Conclusion:

Venture capital founders earn millions of dollars on average. However, venture capital does not assure success – most founders exit with no equity. Applying for venture capital takes months to years, and the prospects of ever succeeding are low (1% of companies that want venture capital will ever get it). Although applying to venture capital can be valuable, it is not an easy or reliable way to achieve startup success.

Appendices

Appendix 1: How many new nascent companies are there?

We estimate that there are over 1 million new nascent companies each year.

Nascent entrepreneurs are defined as individuals who (a) considered themselves in the firm creation process; (b) had been engaged in some behavior to implement a new firm — such as having sought a bank loan, prepared a business plan, looked for a business location, or taken other similar actions; (c) expected to own part of the new venture; and (d) the new venture had not yet become an operating business. p172

In July 2013, the US population was 316.1 million. The portion aged 18-74 was around 69.8%, or 221 million. In 2005, the Panel Study of Entrepreneurial Dynamics (PSED II, Table 3.1) found that 5.96% of America’s working aged population were founders of nascent companies. This figure is quite stable: in 1999, the PSED I found that 5.62% of adults had nascent startup. If 6% of the current US working population of 221 million are founders of nascent companies, this amounts to 13 million individuals. As the average team size is 1.7 (p173), this makes 7.7 million nascent firms. After one year, 12.9% of these firms nascent firms either gather revenue or fail. (Table 2, PSED I, II, Harmonized Transitions Dataset.) In order to achieve replacement, 1 million (12.9% of 7.7 million) firms must be less than one year old. The total number of nascent companies started each year must be more than this. It is unclear whether nascent firms are a precursor to employer and nonemployer firms, or if they are better described as an alternative pathway to applying for venture capital. There are many steps in this calculation, and so it is very approximate.

Appendix 2: How many startups apply for venture capital?

We want to know what proportion of new firms (<1 year) want venture capital. Researchers have not answered this question directly but they have made a variety of related estimates, each using a slightly different cohort:

- According to PSED II, 6% of nascent firms project substantial growth. "6.0%, would be expected to be in the substantial category — more than $4 million in sales or more than 50 jobs or both" (PSED II). Growth is a defining characteristic of a startup, suggesting that at most 6% of nascent firms are true startups. On the other hand, not all of these firms will apply for venture capital, so this figure may also be too high.

Ou and Haynes estimate that 100,000-200,000 (2-4%) of small US firms with employees were candidates for VC funding in the mid-90s. They do not describe their methodology in detail, only saying that: "The estimates are derived from data from the Bureau of Census on high growth firms with at least 5 or more employees in mid 1990s."

In the Kaufman Firm Survey, 26 (0.84%) firms obtained venture capital in their first year. The KFS report noted that the average deal was $1.1 million, not the usual $3+ million. So they hypothesise that many respondents had misclassified their investors "Some firms may indeed misclassify angel investors as venture capital, as the average amounts are quite low".

In the PSED I survey in 1999, 26 (3%) founders of nascent firms had asked for venture capital, and 10 (1.2%) had obtained it. Using data from the PSED I, it is estimated that there were 10.7 million (Table 3.1) entrepreneurs at this time, and so if 1.2% had obtained venture capital, this would amount to 130,000 entrepreneurs with venture capital deals – far too many, considering that from 1987 to 2005 Hall and Woodward discovered only 55,000 deals (The Incentives to Start New Companies). This may be due to sampling error, or may be due to entrepreneurs incorrectly describing angel deals as venture capital deals.

Based on these figures, we estimate that 2-6% of new firms want venture capital. If we think that new firms are more ambitious than those identified by these surveys, then we might give a higher estimate. If better estimates emerge, our guess may change substantially.

Footnotes:

- Hall, Robert E.; Woodward, Susan E. The Burden of Nondiversifiable Risk of Entrepreneurship. American Economic Review 100 (June 2010): 1163–1194. ↩

- From a random sample of 41 VC IPOs with 66 entrepreneurs. Analysis here. Source: p1168, The Burden of Nondiversifiable Risk of Entrepreneurship. Excel data in ‘entfrac’ here. ↩

- "Some acquisitions also return substantial value, while others may deliver a meager or zero value." The Burden of the Nondiversifiable Risk of Entrepreneurship. It is counterintuitive that the number entrepreneurs who exit with greater than zero earnings (25%, according to the model) could be so much less than the total number of companies that have reached IPO or been acquired after a 0-20 year period (35%, according to the raw data). We asked Prof Hall about this and he reported that "Many of the acquisitions are at values that do not cover the investors' preferences, so the entrepreneurs get nothing." ↩

- "Although the average ultimate cash reward to an entrepreneur in a company that succeeds in landing venture funding is $5.8 million, most of this expected value comes from the small probability of great success." The Burden of Nondiversifiable Risk of Entrepreneurship. Their older estimate from The Incentives to Start New Companies was slightly lower, at "$9.2 million in 2006 dollars” per founding team (not per founder). So the average founder is projected to earn millions of dollars. These companies also receive correspondingly high valuations. In 2013, the average Series A pre-money valuation was $10.1 million, according to a survey by law firm Cooley. 2013 Venture Financing in Review by law firm Cooley. ↩

- In 2008, there were 5.9 million employer companies, according to US census data ↩

- In 2008, there were 21.3 million nonemployer companies, according to IRS nonemployer statistics. ↩

- There were 100.6 million American workers from age 25 through 55 in May 2014, according to BLS. 9.97% of American workers from age 25 through 55 are self-employed according to the CPS via Table 1 of Does Entrepreneurship Pay? by Levine and Rubenstein. This gives 10.0 million self-employed from 25 to 55 years old. ↩

- In 2012, there were 798,000 new employers. From BLS, Table 11. Non employer companies are more common than employer companies (21 to 6 million). In 2002, nonemployer companies had a higher birth-rate, of 34.3%, compared to 12.6% for employer companies. From Nonemployer Startup puzzle. So overall, we estimate that there are around 7.9 million new nonemployer companies annually: 7.9 = (7.98)(21)/(6)(34.3)/12.6. This uses the US census definition of a business birth. "A business birth is defined as an establishment for which no predecessor in any previous period is identified that achieves nonzero employment for the first time. Births are a subset of openings." Measuring Job and Establishment flows with BLS Longitudinal Microdata ↩

- There were 100.6 million American workers from age 25 through 55 in May 2014, according to BLS. The number of salaried employers and the proportion who become self-employed are from Does Entrepreneurship Pay, Tables 1 and 2. ↩

- In 2013, there were 1,355 deals that were the first financing for that company (including all rounds, not just seed or Series A). Including follow-on deals, there were 4,100. From PWC. This is similar to the estimates of CB Insights, Venturesource and ~1100/yr, which can be inferred from Hall and Woodward's data (22,000 new venture capital funded startups over a 20 year period). Note that a few venture capital deals made in the US go to international companies, a factor which is ignored by this analysis for simplicity. ↩

- "David Hornik, a partner at August, told me: ‘The numbers for me ended up being something like 500 to 800 plans received and read, somewhere between 50 and 100 initial 1 hour meetings held, about 20 companies that I got interested in, about 5 that I got serious about and did a bunch of work, 1 to 2 deals done in a year." From Paul Graham’s Fundraising Survival Guide. It’s difficult to know if David Hornik reads all applications to August Capital, or if some of the worst are filtered out beforehand. ↩

- "From the fund I work for, and a handful of others for which I have an anecdotal answer, I can tell you that about 0.6 – 0.9% of companies that seek funding from a VC fund end up getting an investment. I expect that varies a fair bit." – Sean Owen from Pentech on Quora ↩

- "To start with, a pre-revenue mobile company cannot expect to raise anything from "the VCs". Venture capital funds invest in only one out of every 400 companies seeking funding" – David Rose, on Quora ↩

- "For every 100 business plans that come to a venture capital firm for funding, usually only 10 get a serious look and only one ends up being funded" – Venture Capital Yearbook, 2014 ↩

- From here. This includes various kinds of funding (not just VCs), with an average investment size of average size $1.7 million. The average accelerator graduate raises an aggregate of at least $350k within 12 months of graduating the accelerator program. ↩

- It is common knowledge in the startup scene that it is crucial to have a prototype, traction and an introduction to attract venture capital. Here are some representative comments: "The best way to find angel investors is through personal introductions. You could try to cold-call angel groups near you, but angels, like VCs, will pay more attention to deals recommended by someone they respect." Paul Graham on Startup Funding. "“The idea is rarely the valuable piece, and also rarely original. Assume the VCs have heard variations of your idea a dozen times already Usually you need more than just a prototype to attract Venture Capital, you need a prototype and traction” – Quora Comment. “While many entrepreneurs may dream of getting investor money while they’re still in the market-research phase, that’s getting less common. Every company presenting at TechStars either already had clients or had at the very least expressions of interest, usually from mid- to larger-sized customers with recognizable names. That’s solid proof that there’s real need in the marketplace for what you’re offering.” – What really makes venture capitalists invest in your startup. There is a lot more advice like this online. ↩

- This is also common knowledge among entrepreneurs. For a representative comment: "What are the odds of a deal getting done based on a solicitation from: an unsolicited business plan submission? Approximately 1 out of 1000. referral from professionals with fund relationships (accountants, lawyers, and market dealers)? Approximately 1 out of 5." VC Odds: What are my chances of raising money from VCs. We also know individuals whose ideas had proceeded quickly to implementation using a personal connection to an enthusiastic venture capitalist. ↩

- "The typical venture capital firm receives over 1,000 proposals a year. Probably 90 percent of these will be rejected quickly because they don't fit the established geographical, technical, or market area policies of the firm or because they have been poorly prepared" “Companies that can expand into a new product line or a new market with additional funds are particularly interesting. The venture capital firm can provide funds to enable this company to grow in a spurt rather than gradually as they would on retained earnings although most venture capital firms will not consider a great many proposals from startup companies, there are a small number of venture firms that will only do startup financing. The small firm that has a well thought-out plan and can demonstrate that its management group has an outstanding record (even if it is with other companies) has a decided edge in acquiring this kind of seed capital.” A Venture Capital Primer for Small Business, US Small Business Administration ↩

- There were 181 first sequence seed/startup deals in 2013, 214 in 2012, 355 in 2011. PWC Moneytree ↩

- 843 seed deals in total, according to CB Insights. They don’t specify how many of the seed deals are the first for that company compared to how many are follow-on deals. ↩