Transcript

Rob’s intro [00:00:00]

Rob Wiblin: Hi listeners, this is The 80,000 Hours Podcast, where we have unusually in-depth conversations about the world’s most pressing problems, what you can do to solve them, and why writing a blog post probably won’t convince Mr Putin to reassess his Ukraine policy. I’m Rob Wiblin, Head of Research at 80,000 Hours.

Many of you have likely heard of today’s guest — journalist Matthew Yglesias — and I give him a thorough intro in just a second, so all I’ll say is that I really enjoyed listening back over this interview, even though I was down and out with COVID when Keiran sent it to me.

Before that though, a reminder that we’ve got two job opportunities here at 80,000 Hours which you might want to think about applying for.

First off, we’re hiring career advisors to join our one-on-one team. Our advisors do video calls with hundreds talented and altruistic people in order to help them find the highest-impact career they can.

We’ve found that people from a surprising range of professional backgrounds can be good at this. If you want to hear more about what it’s like you can get a taste in episode 75 — Michelle Hutchinson on what people most often ask 80,000 Hours.

It’s a London-based role with a starting salary around £65,000, and applications are closing very soon on 20 February so we won’t get a chance to remind you again.

We’re also hiring a new Head of Job Board to improve and expand our job board. You can check out what it looks like now at 80000hours.org/jobs.

It’s already a very popular service but the new job board lead will be responsible for figuring out how the board can help even more people find jobs where they have a huge impact, and manage the team that works on it.

That’s also a London-based role, and a typical starting salary for someone with five years of relevant experience would be something like £72,000 per year. You’ve got an extra week for that one as it’s closing on the 27 February.

If you’d like to learn more about either role or what it’s like working at 80,000 Hours in general, head to 80000hours.org/latest and scroll down a bit to the blog posts announcing each position, or use the links in the show notes. If you know someone who would be perfect for the role, do let them know ASAP so they can put in an application.

All right, without further ado, I bring you Matthew Yglesias.

The interview begins [00:02:05]

Rob Wiblin: Today, I’m speaking with journalist Matthew Yglesias. Matthew originally studied philosophy at Harvard, and started blogging before it was cool — back in 2002, at the age of 21. That got him a bunch of attention, and he went on to write columns at various US magazines, including The American Prospect, The Atlantic, and Slate. In 2014, he joined Ezra Klein and Melissa Bell, among others, to cofound the news website Vox, which has since grown to become a very well-known and widely read online publication.

Rob Wiblin: Matt initially took a management role at Vox, but ultimately found he preferred to work on the creative side, hosting the US policy podcast called The Weeds, as well as writing regular columns. In 2020, he left his job at Vox to write his own personal subscription newsletter called Slow Boring, using a service called Substack. This quickly attracted many paying subscribers, both increasing his income substantially and setting the example that subscription newsletters could be a viable model for independent journalists.

Rob Wiblin: On the book front, back in 2012, Matt wrote The Rent Is Too Damn High, which argued that single-family residential zoning was causing massive harm in the United States. This popularization of academic research helped mainstream the “Yes, in my back yard” movement — the YIMBY movement — which has since gained many supporters and achieved some major legislative victories in recent years.

Rob Wiblin: Then last year, in 2021, Matthew also wrote One Billion Americans: The Case for Thinking Bigger, in which he argued that the US should aim to triple its population by making it more practical and appealing for people to have children, as well as dramatically increasing both skilled and unskilled immigration.

Rob Wiblin: Thanks so much for coming on the podcast, Matt.

Matthew Yglesias: Thanks for having me.

Rob Wiblin: I hope we’re going to get to talk about your views on foreign policy and how to use opinion polling. But first, as we ask everyone, what are you working on at the moment, and why do you think it’s important?

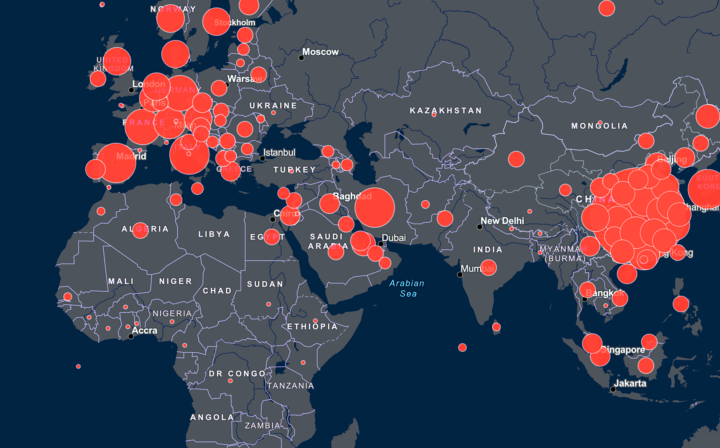

Matthew Yglesias: I work on a wide variety of subjects simultaneously, trying to publish five or more columns a week. But something that has been a theme of mine that I’m working on a piece on right now — one I think is going to continue to be an important subject and that’s very aligned with your audience — is trying to get people to think outside of the day-to-day hurly-burly of COVID-19 policy, and think more about pandemic prevention and biodefense issues as a theme that we should be grappling with on a forward-looking basis.

Matthew Yglesias: Because there will be more variants. There will be more viruses. Things could be worse in the future than what we’ve just been through over the past two years. And yelling about who needs to wear a mask when is ultimately less significant than, “Can we improve our readiness to prevent the recurrence of this kind of problem?”

Rob Wiblin: I’m going to have a few questions about that later on in the interview. And also a few listeners are curious to know what kind of voodoo magic, or what deal with the devil you’ve made to be able to produce so much content, as well as being so active on Twitter almost every day.

Autonomous weapons [00:04:42]

Rob Wiblin: But first off, you’re a really widely read guy who has the specialty of being a public policy generalist. You also tend to be pretty game to do your best to answer just any sort of random, hard questions. So I basically wanted to rapid-fire you a bunch of issues where I don’t already know your views, despite the fact that you have published and said a lot on other interview shows. And though you’re not an expert on these topics, I think you do have plenty of relevant knowledge, so I’m curious to know what you think. Does that sound good?

Matthew Yglesias: Yeah, let’s do it. Lightning round.

Rob Wiblin: Cool. Feel free to skip if you don’t have a solution to some of these quite bedeviling problems. What, if anything, would you like to see governments do about the growing capabilities and use of autonomous weapons?

Matthew Yglesias: This is not a super-deep suggestion, but it seems like you need to have some kind of international summiteering about it — in the way that the US and Soviet Union tried to do these arms reduction treaties about the stockpile of nuclear weapons — because countries are not going to unilaterally want to disavow autonomous weapons systems. But you can imagine an arms race in that area is even more dangerous than the arms race with nuclear ballistic missiles.

Rob Wiblin: The interesting thing about autonomous weapons is it seems to be actually somewhat leveling the playing field between richer countries and poorer countries — it’s allowing countries that don’t have as impressive militaries to potentially create a lot of trouble for more powerful nations. And it might be quite challenging to get them to give up that ability, especially as even the powerful nations don’t seem super keen to give up the option of autonomous weapons either.

Matthew Yglesias: No. This is a challenging problem. But that being said, there was a way world history could have gone after 1946, in which you would’ve said something similar: that just a small stockpile of atomic weapons gives medium-sized countries a great deal of protection against great power–bullying. It’s a very sympathetic-to-the-regime way of looking at it, but this is how the Iranians would say their nuclear experiments have gone. But there was a successful move to really sort of stigmatize that, and have a small number of countries monopolize the nuclear weapons, then have them negotiate with each other to try to reduce the amount that’s in existence. So I don’t think it’s in principle impossible to do, but obviously quite hard.

Rob Wiblin: The same is true actually of chemical and biological weapons, in the sense that the technological barriers there are even lower. And yet we have successfully managed to massively reduce their use, relative to some counterfactual history where they were totally normalized.

Matthew Yglesias: Yes. We don’t think that much about biological weapons these days, because I think we believe we’ve had a lot of success there, but it’s also something worth worrying about more. Obviously, the risk of biological warfare spilling over into the rest of the world is extremely high.

India and the US [00:07:25]

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. OK, which country do you think the United States should be doing more to cultivate a closer alliance with? Maybe one that it is currently neglecting a little bit?

Matthew Yglesias: I think this is a pretty obvious answer, but India is kind of the one that’s on the table. The US has historically been aligned with Pakistan against India in South Asian security crises. Now that we are not present in Afghanistan, we do not have the same kind of dependencies on Pakistan as we used to. And there’s a lot of alignment on values with India and strategic reasons for that as well.

Rob Wiblin: Do you have a take on why it is? I think the US is pursuing a friendlier, closer relationship with India, but it seems like it could be doing more. Do you have an idea of maybe why it’s not?

Matthew Yglesias: I do think that the involvement in Afghanistan has been a complicating factor in that for a long time. The Bush and Obama administrations, and certainly Trump, all made efforts to sort of draw closer with India. But India is very invested in its relationship with its neighbors. Pakistan is very invested in its relationship with India. As long as the United States had thousands of soldiers on the ground in Afghanistan, we needed to prioritize their safety and their security, and that really limited how far we could go with India.

Evidence-backed interventions for reducing the harm done by racial prejudices [00:08:38]

Rob Wiblin: That makes sense. What are some likely impactful or evidence-backed interventions for reducing the harm done by racial and other prejudices in the workplace? A listener submitted this one because you’ve recently written a bit about this topic, pointing out that there are some interventions that have been tested and found not to work. But are there any that you are more positive about?

Matthew Yglesias: One thing that we see is that actually some of the things that are done in the name of racial tolerance training are directly counterproductive. So not doing that would be good. And changing the legal liability standard that has generated those programs is one that we could do. Right now, at least in the US — I assume different countries have different frameworks for this — the understanding of businesses is that if you do something that is called “diversity training,” that that gives you a lot of protection from anti-discrimination lawsuits. So that reduces both the incentive to actually address racial discrimination among your staff, and also to put forward training programs that generate backlash and backfiring.

Matthew Yglesias: So, to develop a legal doctrine in which people are held accountable for discriminatory practices, and are not immunized by saying, “We did some training” — that creates a situation in which big businesses that have a lot of money to spend and have big legal teams have to say, “Look, we need to invest in research. Is there something we can do that will actually improve the situation?” Rather than what they’re doing right now.

Rob Wiblin: I guess you could go further, and say that it’s not enough to just put on programs that say that they’re anti-racism or anti-prejudice. They actually need to put on programs that have been demonstrated to have positive impacts.

Matthew Yglesias: Well, I think you measure by outcomes rather than by inputs. So if you’re going to be penalized for discriminatory practices, then it’s in your interest to come up with a way to have less of them happen, rather than being rewarded for having the program.

Factory farming [00:10:44]

Rob Wiblin: That makes sense. What should we do about the problem of animals suffering in factory farms? Other than the natural answer of supporting the development of alternative protein sources or meat alternatives?

Matthew Yglesias: I mean, the good news — if you want to call it “good news” — about factory farms is that they’re so bad that there’s a lot of room for regulatory improvements at the margin. And relatively small-scale changes — I think we’ve seen some states outlaw the worst kind of egg-laying crates, the worst kind of gestation stuff for pigs — so that’s an obvious approach. I think it’s the one animal rights groups are taking, but it seems really worth supporting to me.

Rob Wiblin: I spoke to Leah Garcés last year, and she pointed out that any regulations that you put in place to improve animal wellbeing on farms — that then increase the price of the products — actually causes some people to shift over to using the often more expensive alternative protein sources, which then builds that industry and helps it to reach a large scale. So potentially, there’s these flow-through R&D impacts that could be quite large.

Matthew Yglesias: It’s potentially a virtuous circle in which you are producing animals in more humane conditions. It’s more expensive to do it that way. There’s more incentive to switch. There’s more value in researching the other things, and also potentially more value on the animal husbandry side in finding cost-effective ways to raise animals more humanely.

Rob Wiblin: Feel free to skip this, but are there any specific animal welfare changes to farms? Or is that maybe getting too specific to be in your area?

Matthew Yglesias: It’s deeper into the weeds than I know. Something I’m sure is familiar to your listeners is just the crude fact that chickens are, by the numbers, the overwhelmingly predominant farm animals. So, even very small improvements in the welfare of chickens has an incredible aggregate impact. The person on the street has not thought that through in that exact way, but it’s actually very, very important if we can make chickens’ lives slightly better.

Wild animal suffering [00:12:41]

Rob Wiblin: I’m not surprised that I haven’t heard you asked this one on other podcasts, at least as far as I know. What should we do about animals dying of hunger, cold, heat, or thirst in the wild?

Matthew Yglesias: This is something that just got on my radar recently as even a topic that exists, and it kind of blew my mind. I may be wrong — and this foundational work may have been done someplace else — but from what I could see looking around in it, I feel like just the very basics, research-wise, need to be done here. Because it seems like wild animals are living in a fairly Malthusian kind of condition, and so you worry.

Matthew Yglesias: I saw one proposal to say that we should actually be vaccinating wild animals, so that they suffer less from disease. Which, that’s interesting — that sounded like an interesting thing to say. But then I started worrying about if you’re going to increase the number but make their welfare even worse by doing that? I honestly don’t know.

Matthew Yglesias: We have a lot of people who study wildlife; it’s a field that exists. But I think that the welfare of animals is not something that we have thought about a lot as a society versus just preserving their habitats. And really just to ask scientists to try to help us understand better what the consequences would be of less disease out there. Unfortunately, we can’t, as far as I can tell, ask predators to use humane slaughter methods. That would be a clear win, but I have no idea how you’d achieve that.

Rob Wiblin: I guess the thing that jumps out that you could try to do for wild animals, at least the larger mammals, is the same thing that has happened to humans: make the resources that they need more abundant, but at the same time have some level of restraint on reproduction — whether imposed or self-generated — so you don’t just get all of the gains eaten up by higher population. But how you do that, I’m not quite sure.

Matthew Yglesias: Right. I mean, I know there’s efforts — not for humanitarian reasons — to use contraceptives to control rat population sizes in urban areas. And that does not seem to have succeeded all that well. If it was working, if this was brilliantly reducing wild rat populations in Washington, DC, I would say, “Wait a minute. We should apply this with the wild animals.” But in the general subject of 80,000 Hours, this feels to me like an area in which we could use more smart people, not just working on the policy question, but actually, “What can we do here? Do we understand this issue? Do the technologies work?” And if they did, I’d be happy to say, “Let’s go out. Let’s go use them.”

Rob Wiblin: At least, “Let’s see what happens when we try it on a small scale.”

Vaccine development [00:15:20]

Rob Wiblin: What’s an area of science that deserves more funding than it currently gets? Even if that funding had to come at the expense of other government-funded science?

Matthew Yglesias: We were just talking about one that I think is interesting here. We have seen that vaccine development is a very promising area. And I have been a little taken aback to learn how little real effort goes into that on a day-to-day basis. There are scientists who believe you could develop vaccines that target whole virus families. And they have some money — they have jobs and things — but the advance market commitments that were made to help spur the mRNA vaccines for COVID, that seems very useful. To tell people, “Look, if you make this, we will buy seven billion doses of it.” That might involve spending no money, but it might involve spending a very large amount of money. And it could help sort of drive private-sector dollars and innovation in a very useful way.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah, we’ll stick up a link to the Wikipedia entry on advance market commitments, and why they’re potentially really useful for spurring innovation at the commercialization level.

Anti-aging research [00:16:27]

Rob Wiblin: Should we direct more biomedical research to slowing down the rate at which people age?

Matthew Yglesias: I’m not against that. That’s one where I have trouble seeing why the private market wouldn’t deliver on there. I feel like there would be a lot of money in an anti-aging pill — you know, targeting the developer.

Rob Wiblin: That’s a good point.

Matthew Yglesias: Again, if somebody tells me, “I’m working on anti-aging research,” I’m not going to be like, “What the hell, man? That’s horrible.” But I think the basic biomedical issue tends to be that we have a lot of private R&D for problems that are common and that impact rich people — so baldness, aging in general, things like that — whereas malaria is a big deal, but the people it affects are mostly poor. And so we could really use more public sector or philanthropic money there. So I don’t know. I mean, I will change my view on that if someone tells me there’s a huge market failure there, but it seems like something that commerce should address.

Rob Wiblin: It’s a good point. My guess is that the anti-aging folks might say something like, “We really are able to make massive progress on this in our lifetime, and might be able to get to a product that’s broadly useful, but it is decades away and so anything that we research now or patent now would have expired by the time you can actually make a product.” So you kind of have this gap between the basic research and the application, where we need external funding in order to get past that.

Matthew Yglesias: A broader question is our regulatory framework for clinical research in general, which is something that I’ve gotten quite concerned about. There’s a good book by a guy named Alan Wertheimer, called Rethinking the Ethics of Clinical Research. This is a philosopher who hadn’t been a bioethics guy, and then, at the end of his career, he did a fellowship at the National Institutes of Health, and he wrote this book. And it’s basically like, “What the hell, guys? Why aren’t you applying the normal ethical concepts of consent to these research things? Why is there this much of a higher standard in the bioethical world?” He’s not even saying you should be the most crass version of a consequentialist you could imagine, that’s like, “Maybe we can do secret experiments, but it’s for the greater good,” but it’s like, “Why can’t you accept the normal standard of ‘voluntary’?”

Rob Wiblin: That we use almost everywhere.

Matthew Yglesias: Right. If you want to get somebody to go work on a fishing boat, you’ve got to pay them more than for other blue-collar jobs, because it’s more dangerous. But if you want to do it for money, that’s a perfectly legitimate career option. But that’s not true for clinical studies. And there’s a lot, separate from the funding side. I do think that we could be making faster progress on all the biomedical fronts if we relaxed the standards for what constituted “voluntary.”

Should the US develop a semiconductor industry? [00:19:13]

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. Should the US do what it takes to develop a domestic semiconductor industry, so it isn’t so dependent on places like Taiwan or the PRC?

Matthew Yglesias: Yeah. I think the expected value there is positive. I’ve read this article in The Economist that was really dumping on the ideas of US and EU semiconductor production. They were like, “It’s going to lead to wasted money and overcapacity” — but how bad is that? Say they’re probably right. Probably it’s fine. Probably it’s a waste of money. That doesn’t sound so bad, versus how a minor disruption to semiconductor production has been a big problem over the course of this pandemic. You could imagine that getting way worse. I mean, an actual shooting war between China and Taiwan is not that unlikely in the scheme of things, and preparing for that in different ways seems easily worth doing.

Rob Wiblin: It sounds like that article might be slightly missing the point, which isn’t that doing this is economically efficient in the median case — it’s a variance-reducing play, which is expensive typically, but you’re buying insurance against a bad outcome.

Matthew Yglesias: I like The Economist. I appreciate free markets — I sometimes scold progressives for not doing enough to appreciate free markets. But I think we know that financial markets do not adequately insure against low-probability, high-severity risks. That’s true of truly existential risks, but also just of any kind of low-probability events. You can’t get insurance against massive disruption of the semiconductor industry. So then there’s no investment in the hedge against that, and we need governments to reduce downside tail risk. It is worth some short-term efficiency loss to do that.

Rob Wiblin: I actually think maybe the best argument against developing the ability to make these kinds of products locally is that the dependence of the US on China is actually really good, because it reduces the risk of war — that we should want the US to back down, because it would be so bad for the two countries to go to war. In fact, it’s perversely good that the US can’t stand on its own two feet. But I mean, it’s an interesting and slightly counterintuitive argument — it sounds a bit too clever by half.

Matthew Yglesias: Well, that was Norman Angell’s argument before World War I. He said we have so much economic interdependency that the costs of European great power conflict would be so high that it can’t possibly happen, because it would be totally irrational. I mean, that was correct: World War I was very costly — everybody ended up much worse off as a result of that. But it didn’t mean it didn’t happen. So I hesitate to put too many eggs in that basket.

What we should do about various existential risks [00:21:58]

Rob Wiblin: Let’s partially move on and talk about existential risk–related policy issues specifically for a little bit. In a recent review of the film, Don’t Look Up, which is on Netflix, you had this great bit that just made my eyes light up. It was about major threats to humanity’s survival. If you’ll forgive me, I think it’s worth reading it for listeners, because I just love it so much.

Rob Wiblin: “I don’t want to tell you that there has never been a story in the mainstream press about supervolcanoes, but there really aren’t very many. There’s no mainstream constituency at all to fund a larger scientific effort to understand supervolcano risk and how to mitigate it. And a candidate for office who goes on ‘Meet The Press’ to say one of his top priorities in Congress is improving US efforts to tackle supervolcanoes would be roundly mocked.

Rob Wiblin: “I don’t think this is because journalists are bad people who want us all to die in a spectacular accident. But we’re a bunch of apes who’ve evolved to be very attuned to the machinations of high-status apes so that we can navigate the factional landscape effectively. The reporters and the editors and producers they report to are apes, programming for an audience of apes. So you get a lot of stories about who is fighting whom and through what means. […]

Rob Wiblin: “By contrast, on something like Covid-19’s origins, we’ve had a decent amount of coverage of the lab leak controversy but essentially no coverage of what is being done to prevent future lab leaks (basically nothing) or to prevent future zoonotic crossover events (again, nothing). […] But again, either way, we’re not doing anything to counter either route for transmission, and that (shocking! alarming! insane!) fact gets way less attention than the latest round of ‘who’s yelling at whom about masks?'”

Rob Wiblin: So normally I dedicate a lot of the interview to kind of fleshing out exactly that issue about public rationality. Except we’ve already covered it a fair bit in 2021 — with guests like Carl Shulman, and Ezra Klein, and Andrew Yang — so that might feel like a bit of a repeat for listeners. But is there anything you wanted to add to or highlight from that extract?

Matthew Yglesias: No, you’ve had a lot of people on the show talking about this. I think it’s great that there’s a community that is talking about this, and the only real question is how do we carry that message forward to more people? And it’s why I liked that movie, despite some of its problems as a climate analogy. I want to encourage more people to do pop culture about existential risks. I think that’s a meaningful way of increasing engagement.

What governments should do to stop the next pandemic [00:24:00]

Rob Wiblin: So in lieu of discussing why politicians don’t make x-risks part of their policy platform, which I guess people probably do understand, I wanted to give you a chance to mention any specific things you think might actually be worth doing about these various huge risks. Obviously this is super challenging, and I’m asking because often I don’t have a clue — so if you don’t have any ideas, feel free to pass.

Rob Wiblin: What would you like to see governments do to stop the next pandemic getting started at its source, whether that is from animals or from labs?

Matthew Yglesias: We talked a little bit about vaccines and advance market commitments, but I think that we should be trying at least to develop these family-wide vaccines. That can allow us to get ahead of viruses that literally don’t exist right now, because we know something about the parameters in which they might emerge. We also do have to look at not the lab leak per se, but I think the prevalence of gain-of-function research is very dangerous. We should be pursuing efforts to sort of tamp down on doing that.

Matthew Yglesias: There’s also mid-range stuff on surveillance and detection that could be useful. John Hickenlooper was talking in a Senate hearing recently about what we would need to do to scale up genomic surveillance — basically look at the wastewater of different American cities and be kind of constantly scanning to see if there is anything new popping up in here. The technology to do that exists. It costs some money. It’s the kind of thing where it would be wasteful on one level: you’d be running a lot of sequencing of people’s poop and not finding anything in it. But it’s good to put that infrastructure in place before you actually need to use it, so it could be available in somewhat of a timely manner.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah, I’ve only vaguely followed this story, so maybe you can correct my understanding here, but I’ve seen Dr. Fauci giving congressional testimony, claiming that the US doesn’t fund gain-of-function research. But it seems to me like it’s kind of a semantic game, where he’s claiming — based on some very narrow technical scientific definition of exactly what gain-of-function research is and what it isn’t — that they aren’t.

Rob Wiblin: But the thing that we’re actually worried about is making viruses that could cause a massive pandemic. And they are doing that — or potentially they’re funding research like that — even though it’s not technically, by their definition, called “gain-of-function research.” Is that your understanding?

Matthew Yglesias: Yeah, there’s definitions splitting on both “What does it mean to be funding something?” and “What does it mean for something to be gain-of-function research?” But I think that there is a philosophy that trying to make more dangerous pathogens is a very important way to develop defenses against the pathogens. There’s always been this ambiguity in the biowarfare space between you’re not allowed to try to develop offensive weaponry, but you are allowed to try to develop defenses. So there’s a strong military incentive to essentially smuggle offensive weapons development under the heading of, “Well, we need this for defense.”

Matthew Yglesias: I think that we should be looking at that telescope through the opposite end of the lens — really trying to clamp down on what we’re doing there, and then develop other ways of thinking about defensive research. If you could develop defensive technologies that don’t depend on you understanding the most small-grained details of the virus’s protein arrangement, then you don’t have the excuse that we need to be constantly fiddling with them in order to see if this stuff works.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. I think it’s interesting that in March 2020, people were really up in arms about this issue that everyone was assuming that COVID had come from a wet market in Wuhan — that it was because of people having all of these live animals in a market, and then people eating them, having close exposure. People were incensed by this, understandably, and talking about how we could get rid of it. As far as I know, nothing’s been done and it’s completely disappeared from the agenda. Like, how much would we have to pay China to shut down the wet markets? How many billions of dollars would it cost? And wouldn’t that be worth it?

Matthew Yglesias: There’s been this extreme literalism of this debate, where people felt sure that it had come from a poorly supervised wet market and were really fired up about shutting them down. But the reason they thought it came from a poorly supervised wet market is that ex ante that seemed very risky.

Matthew Yglesias: Now subsequent analysis has cast doubt on the idea that it actually did come that way. But the whole premise that that’s a risky thing to be doing, that’s still true, right? So now the Chinese are in a blame-shifting exercise — they have some frozen food theory, and I think that that’s wrong from what I’ve heard from people with technical capabilities. But as a forward-looking question, that doesn’t matter, right? Clearly, having a very wide array of live animals in very close proximity to each other and close proximity to urban areas — with creatures being brought in from all different parts of the world — that is dangerous. That is biologically dangerous.

Matthew Yglesias: It’s not that high-value to China either. There are things that it’s hard to get cooperation on because they’re so important, but the Chinese government has fitfully tried to marginalize these things over the years for different reasons. And then it’s culturally sensitive issues, so they get pushback, et cetera, et cetera. But it’s frustrating that you can’t get a real move there.

Rob Wiblin: I was just thinking, what could actually be done? I wonder, could the US just say, “Look, give us a list of everyone who works in every wet market in China, and if they shut down their thing and don’t open up a new one, we’ll give each one of them a million dollars.” Seems like it would be an absolute bargain. I don’t know, maybe a million is too much. At that price, it wouldn’t be worth it. But what about $100,000? Would they be willing to go get a different job for that?

Matthew Yglesias: Right, exactly.

Rob Wiblin: I guess this is the kind of thing that economists think is very sensible, but then you just know in your gut that this could never happen for some reason.

Matthew Yglesias: Unfortunately, it’s not a super cooperative environment between the US and China right now. This is again one of these things that’s understandable but unfortunate, that there is a lot of psychology about not looking weak happening in different places. So the question of who is making a concession to whom feels very significant to everyone, and that makes it hard to take any kind of concrete action — even though really the stakes here are not that high, and people’s interests seem fairly aligned.

Matthew Yglesias: I do think that the most likely way to get Chinese wet markets cracked down on is for the Chinese to do it on their own — unilaterally, not under pressure from the United States — just because they decide they would like to. For them to look like they were backing down is not something they would want to do. And for Western countries to seem like they were bribing China is not something we would want to do. So I hope Xi Jinping listens to your show, and is just going to do the right thing here.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. It is interesting that perversely neglecting and not talking about this issue might be the best way to solve the problem.

Matthew Yglesias: You never know, right? As a person who likes to talk about things, I would always like it to be the case that shining more attention on a topic is the solution. And it is for some problems, but unfortunately not for everything.

Comets and supervolcanoes [00:31:30]

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. What, if anything, would you like to see the government do about comets and/or supervolcanoes?

Matthew Yglesias: NASA poked around on the supervolcano issue a few years ago, and they seem to have the idea that you could try to cool down the magma underneath Yellowstone with essentially injecting water. That’s related to the idea of advanced geothermal as an electricity-generating concept.

Matthew Yglesias: So there are these regulatory sensitivities around geothermal drilling on federal lands — a ton of sensitivity about doing it in an actual national park, which is where Yellowstone is. But I think that sacrificing a portion of the park in order to not have literally the entire planet explode would probably be a win-win. And we could offset that with some more parkland someplace else. Again, as you would expect, it’s not totally clear that that would work, but it’s worth investing some money in the exploration of whether or not it works. There’s a few other supervolcanoes that are out there.

Matthew Yglesias: As I understand it, after Deep Impact and Armageddon came out, we actually got the government to track asteroids better. And comets are just a little bit harder to track: they come in at a sharper angle and they go further away. But we should put some more telescopes up there and try to find them.

Matthew Yglesias: There’s a lot of nostalgia for the kind of heroic age of NASA and space exploration, which was very motivated in its heyday as a kind of national defense imperative against the Soviet Union. Today I don’t think that you can very plausibly claim that we need to go to Mars to stick it to China. But there’s a very clear national defense rationale for comprehensively tracking objects in outer space as far away as we can.

Matthew Yglesias: The amount of money that’s spent on defense programs is very, very, very large, and tracking those comets is good — especially as we have more private sector interest in some of the sort of sexy low-hanging fruit of, “Let’s get some human beings and have them go around the Earth in a circle.” You know, good for the entrepreneurs. And there’s not a huge ROI financially in tracking comets, but socially it’s very valuable.

Rob Wiblin: Just a few weeks ago, we saw the James Webb telescope go up, and obviously it has an unbelievable ability to detect objects that are extremely far away — in this case, billions of lightyears away. So I don’t understand the technology, but I figure there must be some way to turn money into the ability to see comets that are further away than what we currently do, if we really set our mind to it.

Matthew Yglesias: I think that this is just a question of how much of the field of view are we actually looking at, at any given time. You need more than one telescope and they’re expensive.

Nuclear weapons [00:34:25]

Rob Wiblin: Any ideas for how to reduce the risk of a war with nuclear weapons? Or reduce the number of weapons that are used if one does occur?

Matthew Yglesias: Not really. [laughs] I mean, we got to do our best. We’re probably going to talk about my sometimes-unpopular opinions about Russia out there, but you’ve got to ask yourself with any kind of international conflict: is the juice worth the squeeze? And conflict between the US and Russia is very dangerous. It’s worth asking yourself what the stakes really are, and what the upside to some of these things is.

Matthew Yglesias: US and China is the more hot geopolitical topic. China does not have that many nuclear weapons right now. We should be keeping in mind: how can we keep it that way? And anytime the US and Russia can agree to reduce our nuclear stockpiles, that has a safety benefit — in terms of that bilateral relationship, but also in terms of reassuring the Chinese that they do not need to embark on a crash program to drastically increase the number of nuclear weapons they have. Theoretically, the major nuclear powers committed to disarmament some time ago. They’re not actually doing that, but anything that’s done that counts as baby steps in that direction is useful.

Advances in AI [00:35:46]

Rob Wiblin: Do you think we should do anything more now to prepare domestic society or the international order for the possibility of major advances in AI over the coming decades?

Matthew Yglesias: We definitely should. The question is always what, right? As the person who asks the questions on podcasts, I’ve had people from the effective altruism and longtermist world on the show. Or just talked to them informally, to be like, “What should I do? Say I decide that I take AI risk extremely seriously. What do you want me to say about this?” And their answers always strike me as fairly fuzzy, so I’m left at a bit of an impasse.

Matthew Yglesias: Now again, to the young people out there, if you are technically literate and you’re in your early 20s or late teens and wondering what to do with your life, there is a lot of demand for good ideas about incentive-compatible artificial intelligence — how to make this maximally beneficial rather than threatening to humanity, on a policy level. I’m in the market for hot takes.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah, I think that there are policy ideas coming up through the academic conversation, but it does still feel like the conversation is pretty preliminary. And they seem fairly reluctant to go out and publicly advocate for anything in particular, which is interesting. I suppose they just worry that their ideas could do more harm than good a lot of the time.

Matthew Yglesias: That’s definitely a risk that’s out there. And I worry sometimes about how you have communities, or you have schools of thought — and that’s good. But sometimes something can become a scene. It’s like to be “in” in part of the tribe, you’d be like, “Oh, I’m really worried about AI existential risk.” OK, but “being worried” about things doesn’t accomplish anything in life.

Matthew Yglesias: And you can just kind of dismiss other problems. Say, like, “Well, don’t worry about that — worry about the AI risk.” But is there a tradeoff? Is there something that a typical person — a typical elected official even — should be doing differently? I’m not sure. I’m not saying no, but I haven’t been super convinced, in the way that I have on pandemics or even supervolcanoes. There are these kind of fiscal tradeoffs in the NASA budget, in NIH — what they care about that really addresses existential risk on those topics.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. 80,000 Hours to some extent exists to try to solve this problem. I guess we have good ideas, as you were suggesting, for what you should do if you’re early in your career, or you’re willing to fully change your career to go and become a domain expert in a particular policy issue or some particular technical problem. But it has been a lot harder to come up with one like, “You’re a 40-year-old generalist who has a lot of Twitter followers. What should you do?” We haven’t quite nailed that one yet.

Matthew Yglesias: It’s a tough one. I’m pretty useless. I don’t know.

Surveillance systems [00:38:45]

Rob Wiblin: [laughs] What would you like to see governments do about the threat that surveillance systems or technologies could be abused for oppressive or authoritarian purposes in the future? Including in countries where it’s not obvious that they definitely will be used that way.

Matthew Yglesias: Is that the future or is that the present? I’m not really sure. What should governments do about it? I don’t know. I tend to think that we sometimes — in the United States at least — over-index on “Let’s not use this technology for good, because in principle it could be used for evil.”

Matthew Yglesias: I see what people are saying about that. So in the UK you have a lot of CCTV cameras around everywhere, and the police can use that footage to try to catch murderers. And that’s very stigmatized in the United States, because it’s seen as a privacy risk and an oppressive government could use that technology to do really bad things. I never find that all that persuasive. If the oppressive government takes over in the future, I don’t think it’ll be that hard for them to install the cameras.

Matthew Yglesias: I don’t want to say it’s an overrated problem, because it’s obviously quite a serious problem. I think the PRC has developed a level of oppressiveness that is beyond the capabilities of 20th century states. We know 20th century totalitarianism was worse than the worst governments of the 16th century because they had more capacity. So it’s a big issue, but I don’t know that having liberal states refuse to develop state capacity is a good answer to that. On some levels, we need to be as capable as we can: we want to show that liberal states can succeed and can deliver good governance in an effective way and not just lose out.

Rob Wiblin: I can see what you’re saying about not deploying the cameras — it doesn’t super help, because a malicious government can just buy some cameras and stick them up. But it seems like it’s worth imagining in like 10 years’, 20 years’, 30 years’ time that the US government, the executive, was trying to use the things that we imagine they’re going to have to oppress and suppress their political enemies.

Rob Wiblin: What other things could we do to make it more difficult? Like legally, potentially, to slow this down? You’d have to wait for the judges to die and be replaced in order to be able to get something through. Or if you don’t control Congress — Congress has passed these laws in the past — making it very difficult to do X, Y, and Z, in order to buy time. That potentially seems worth doing.

Matthew Yglesias: Yes, I’m for civil liberties, like normal people have and do. Americans are very invested in the idea that a certain kind of proceduralism is safeguarding our liberties. And if you look cross-sectionally at the UK, at Canada, at Ireland, at Australia, New Zealand — I don’t actually find that very compelling, that all the countries that have this kind of Anglophone cultural heritage have sort of similar social values, sort of similar outcomes. We actually have wildly different baseline political institutions.

Matthew Yglesias: The US and Britain diverged incredibly sharply in the late 18th century in our concept of what to do about the king oppressing you. Britain went all-in on parliament — “We should democratize the parliamentary elections. We should empower the House of Commons” — and you now have this hyper-sovereign unicameral legislature. We went the other way: we’re all-in on counterbalance theory, and our version of the House of Lords is super important, we have all this federalism, et cetera. I don’t know that that stuff has given us any more practical liberties or a real safeguard against tyranny on a practical level.

Rob Wiblin: Maybe the case is clearer in the UK. I guess you’re saying that our protection is actually the values of people in the society: that an individual person who wants to abuse technology this way won’t be able to, because people will stop them because they don’t like it. And that makes a lot of sense.

Rob Wiblin: But what would you do if you wanted to add more safeguards? In the UK, it seems like Parliament does just have a lot of authority to do pretty crazy stuff if you could get a majority to go with it. I might feel happier if there were more safeguards to stop Parliament really going off the rails. I think Parliament probably won’t go off the rails, just because of the culture of the UK and of the UK political class, as you say. But I don’t know whether I want to bank everything on that.

Matthew Yglesias: Yeah, we’ll see.

How Matt thinks about public opinion research [00:43:22]

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. OK, let’s move on and talk about how you approach using polling and other indications of what voters think to shape the ideas that you advocate for. This is another topic where a few of my followers thought that you had the wrong idea, or at least the wrong idea in specific cases. When you’re researching a problem, like climate emissions or childhood poverty in the US, how do you personally use indications of public opinion?

Matthew Yglesias: Oh yeah. This is one of these things where you wind up sometimes in life getting backed into lines of work that you didn’t expect you would be in. And I should maybe reevaluate. But something that I have found is that the world of public opinion research is kind of bifurcated — or trifurcated, if that’s a word.

Matthew Yglesias: On the one hand, you have people doing polls to go to the media, for public consumption. Then you have people doing polls to issue advocates, who want polls that say their positions are popular. And then you have people doing polls because they’re trying to win campaigns. Survey methods are the same across these things, but what your incentives are and what you actually care about are pretty different.

Matthew Yglesias: Unfortunately, for the mass public, to get a good read on public opinion — like a rigorous look at how things are without putting a lot of English on it with question wording — you do have to talk to the people who are doing private work for political campaigns. They are the ones who have the strongest incentive to get the question right — not in terms of the survey sample, but in terms of what questions you ask people.

Matthew Yglesias: I know there’s a couple guys on Twitter who are very angry that I say carbon taxes are unpopular.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. That was one of the people who put this on Twitter.

Matthew Yglesias: They’ve got their polls that say it’s popular, but we know in America that when this has been put to ballot initiative in Washington State, it’s lost badly, twice. We also know that in Europe, where the macropolitics is greener than in the United States, the European elected officials act as if stiff carbon pricing is going to be very unpopular.

Rob Wiblin: In what way? They don’t talk about it?

Matthew Yglesias: And they don’t do it, right? Because they don’t —

Rob Wiblin: Isn’t it that the EU carbon market is… The price per ton of carbon isn’t that low now, right?

Matthew Yglesias: It’s pretty low. And they do all this other kind of green stuff, right? And their opposition parties aren’t winning elections on the basis of these things. In Australia, when the government tried to put a carbon tax in place, there was a big backlash to it.

Matthew Yglesias: So people say that if you do the best kind of issue surveys, where you do partisan frames, you say, “Some Democrats are proposing a blah, blah, blah, price on carbon, which they say will reduce climate change in the most cost-effective way possible. Republicans say it’ll raise the price of gas by…” — then you give them a real number, not a crazy lie: “It’ll raise the price of gas by so many cents, raise the price of electricity by so much.” It becomes incredibly unpopular in that framework — like, less popular than commercial legalization of heroin.

Matthew Yglesias: When the price of gasoline spiked in the United States a few months ago, it was a huge deal politically. People were losing their shit about it. Probably the best media poll on this is a Reuters survey where they asked people, “Should we take drastic action to stop climate change?” Most people said yes. Then they asked, “Would you be willing to pay $100 a year more in taxes to stop climate change?” People said no. A hundred dollars a year is not that drastic, you know? I spend $100 a year on things that I don’t think are important at all.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. It’s 0.2% of the average household income or something like that.

Matthew Yglesias: Right. I don’t want to say it’s nothing, but I mean, I’ve given $100 to charitable causes that I don’t even think are very good causes, just because somebody asked me to and I had a relationship with them.

Matthew Yglesias: So I think that it’s tough. As a professional journalist, the kind of thing that I can do is ask people to tell me things that they cannot say in public, and then I can try to triangulate the things that they have told me against publicly available information — like this Reuters thing, like the Washington polls, like the fact that practical politicians don’t campaign heavily on green tax shifts — and try to make people sort of see the truth. But it’s hard. I never know, because I’m not a huge scoops guy, and if you want to believe that I’m lying to you or that my sources are lying to me, it’s challenging to prove otherwise.

Rob Wiblin: I see. So the issue is that you’re getting what you think are the most reliable indications of public opinion, and also where public opinion would go if this became a live political issue, from people who are working on campaigns. And the polling data is private or the research is private, so you can’t share it. Sometimes it conflicts with perhaps advocacy polls that have been put out, or perhaps less high-quality public polling from Gallup, where maybe the question’s not quite right. Or they haven’t really tried to stress test how long will people really believe this, if it started costing money?

Matthew Yglesias: It’s the stress testing in particular that’s important. There’s a phenomenon called acquiescence bias, where if you ask people questions, they’re inclined to say yes. Researchers used to think that this had something to do with talking to people on the phone, and they were very bullish when internet polling first started. They thought they were going to get rid of this, but they didn’t. Which seems a little odd, because you could imagine that you don’t want to fight with the guy on the phone — you want to agree. But it’s quite common, and unless you give people the argument/counterargument, you can show that all kinds of things are popular, and contradictory things.

Matthew Yglesias: This is not breaking new ground — this is Converse’s classic work on public opinion. But people don’t have really deep and consistent views, which sometimes gets taken to mean that you could get away with anything in politics. But that’s also not true: there’s very consistent patterns of public backlash and resistance to things that raise middle-class people’s taxes — in particular to high-salience taxes, to increases in the cost of energy. You see that not just in the US, but really around the world.

Matthew Yglesias: I think a very underrated thing for American progressives looking at politics, is that we’ll look across the ocean and say, “Oh, these Europeans, they have these great healthcare systems. Why can’t we have one like that?” The answer in a lot of cases is that the healthcare systems were created decades ago, when the cost of providing them was much, much lower, and so it was done with small taxes. And once it exists, people become very attached to it. If the quality of the healthcare services degraded, they are in fact willing to put more funds into it for the sake of better services.

Matthew Yglesias: But because we didn’t adopt a universal healthcare system when Truman was president, or when JFK was president, we are now stuck with the present-day cost structure, and it’s just a much heavier lift to get people to embrace it. The 2022 cost of the National Health Service was not presented to the British public in 1948 — they got the 1940s cost, and it’s good for Clement Attlee.

Issues with trusting public opinion polls [00:51:18]

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. OK, I’ve got a couple of uncertainties about how this works in practice. I think one objection will be to say, you’ve got these different categories of polling. You read any individual poll and it’s really hard to tell what the motivation was of the person who originated it. Is the question quite right? What other followup questions were there? Could a different group have said a different thing? And you’re having to refer to these private conversations with people who won’t talk to most other folks, and then they might disagree as well.

Rob Wiblin: It just seems like this is a real mess to analyze. And that’s demonstrated by the fact that different people who have similar policy preferences ultimately, actually disagree about what they think the public might favor if push came to shove. Maybe this enterprise is a bit doomed, and instead we should just be advocating for what we think is substantively best, because at least we can do that.

Matthew Yglesias: I do think it’s a question of who “we” are. I have stumbled, I would say, a little bit ass-backwards into being a guy who writes a lot about polls and public opinion surveys. And it was not my intention, exactly — I don’t know that it’s super important for the typical person to be deeply, deeply invested in this. The main thing that I would like the person on the street to take away from it is that workaday politicians running for office are probably better informed about the state of public opinion than you are. And if you are finding yourself baffled as to why someone won’t say something or embrace something that you think they should, it’s probably because their surveys indicate that it’s not that popular, and maybe try to be a little less mad.

Matthew Yglesias: Now, what should you advocate for? Whether it’s you, or the listener, or whoever else, you probably should advocate for the right thing to do. And you should probably advocate for the right thing to do as if you were trying to be persuasive, which I think people oftentimes don’t do on the internet. I would say heavy consumers of political punditry spend a lot of time pounding the table on behalf of what they think is the right thing to do, being very impatient that other people in positions of greater responsibility aren’t saying exactly what they want them to say, and searching for bias-confirming information that indicates that they are right about everything.

Matthew Yglesias: Now, I don’t think any 80,000 Hours people are actually in that headspace.

Rob Wiblin: Oh, I mean, come on. I’m in that headspace. We were pounding the table earlier about the Chinese wet markets.

Matthew Yglesias: I mean, everybody is sometimes, but like…

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. We’re not the worst offenders there.

Matthew Yglesias: I don’t think it’s huge breaking news out here to tell people who listen to your show that people spend a lot of time on pseudo-arguments and confirmation bias. I try to be more of a rationalist than the average political pundit, more of an effective altruist than the average political pundit. But I really am a political pundit, whose life is mostly responding to other people in the punditry space — and there are a lot of bad arguments, wrong ideas, fallacious information going around on these subjects.

Matthew Yglesias: I’ve gotten into some pushing back on it, some level of audience interest in these kinds of ideas. But most of all, something that absolutely is just relevant to your main topics here, is that there are lots of ways of making political change that do not involve leaders of political parties pronouncing the right thing in the heat of a political campaign, in a high-profile media way. Right?

Matthew Yglesias: That is a thing that happens in politics: people are like, “Our campaign is going to be waged on X, Y, and Z, and we’re going to elevate that to the top of the discourse.” It’s an important part of life. It’s an important part of policy change, but it’s absolutely not the only way that policy changes. I think it’s only a good way to change policy when you are really, really convinced that public opinion is behind you.

Matthew Yglesias: Like we were talking about before, I wish the government would do something about supervolcanoes. I think it would be crazy for Joe Biden to give a State of the Union address where he is like, “My fellow Americans, there’s a 1 in 10,000 chance that a large magma deposit under Yellowstone National Park…” People would think that was bizarre, and he shouldn’t do it.

Rob Wiblin: I’m not sure whether that would help or hurt. I have no idea what effect that would have.

Matthew Yglesias: I don’t know either. I’ll put it this way. If the pros tell me, they’re like, “Matt, we did you a favor: we looked at that, and it sucks,” I think that’s fine. What I am asking them to do is see if they can’t have a conversation, staffer-to-staffer, in the Interior Department appropriations, where they get some money to say like, “Does this Yellowstone cooling idea work?”

Matthew Yglesias: And you want to find bipartisan cover: you want a Republican — ideally one who represents Wyoming — to be like, “Yes.” (I think Yellowstone’s in Wyoming, apologies if it’s someplace else.) But it’s a big problem, and someone should do something about it. Which does not mean it should be the centerpiece of a national political campaign.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. Another general concern I have in this area is the idea that just a random person who you might phone up has opinions about the child tax credit or all of these other policy issues that someone somewhere cares about, and wants to know what people think. They have no opinion on so many things, just as I have no opinion on the great majority of topics, because I’ve never thought about them and I don’t really care about them.

Rob Wiblin: One of the reasons why it’s so hard to suss out what people think is that sometimes they just don’t think anything about it, and so we don’t know — until, I guess, it becomes a partisan conversation and we see how people react to news stories and so on. But maybe the whole thing of, “What is public opinion about X or Y” is kind of malformed in a sense, and it’s super unstable, and there is no real answer.

Matthew Yglesias: I think that there’s a level on which that’s true and a level on which it’s not true. One thing you can see is that we have referendums and initiatives pretty frequently in the United States, so you can relate how those referendum outcomes look compared to early polling on the thing. Academics who study this say that it tends to fall back to baseline — that really popular referendums underperform, and really unpopular ones overperform. So the argument kind of pushes people a little bit back toward the center, but only modestly so.

Matthew Yglesias: But if you do a good survey, that proposes that there will be an argument and says that there are two sides to the issue… It’s true that most people have not really given much thought to most issues, but their gut reaction to a pro and con argument is pretty predictive about where they’re going to be at the end of the day — precisely because they’re not deep reflectors on it.

Matthew Yglesias: Now, what would be harder to say is, “What would people think about this subject if they studied it intensively for months?” But they’re not going to study it intensively for months. What they’re going to see is some pro and con ads on television occasionally, that they do not engage with very deeply. Just as I’m sure there’s lots of things you don’t have an opinion on, but somebody who knows you well can develop a pretty good mental model of you. Or they don’t even need to know you that well, to be like, “OK, this is a longtermist, this is an effective altruist, this is a cosmopolitan — so how is he going to come out on this question that I am factually well informed about once he becomes better informed?” Because we can make these kinds of predictions.

Matthew Yglesias: You asked me at the top of this what my opinion was on a bunch of stuff that you didn’t know what my view was. But I doubt I really shocked you on any of those answers, right?

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. That’s true.

Matthew Yglesias: Because you have some information about the general argumentative landscape.

Rob Wiblin: You’re a somewhat unusual person though, in that you think about these things all the time, so you have a more structured framework on how you approach these questions. Whereas many people’s interests are not primarily public policy, so they’re perhaps more likely to form somewhat random opinions based on what they heard.

Matthew Yglesias: Well, I think what you see people default to is selfishness and short-term thinking, right? That’s the sort of core underlying constraint of public opinion in a democracy. A very valuable thing we can do in the world is push people culturally, personally, to be more broadminded and less shortsighted in their thinking.

Matthew Yglesias: This is why climate change is a difficult problem, because you’re asking people to make sacrifices for the long-term benefit, largely of foreigners. It’s not that hard to convince people that greenhouse gases are real or that it would be desirable to have climate change not happen — but it’s very hard to push people to make changes in their personal lives or to embrace policies that would force them to change. But if you can obscure the costs or do things that seem like win-wins, like we’re going to develop carbon capture technology. We’re like, “Oh, yeah, that’s great. It sounds good. Let’s go do that.”

Matthew Yglesias: And it’s exactly why it’s so much easier to get me to agree that factory farmed meat is a moral problem than to get me to stop eating it — because, I don’t know, I’m a bad person, you know? I try to be better. I eat less than I used to and I espouse a lot of correct positions. I like to think that I could bring myself through to vote yes on a ballot referendum that would make this more costly for me — that I am at that level of reflectiveness. But we are weak, pitiful creatures.

Rob Wiblin: This is reminding me, I have this kind of cached belief that middle-class people don’t want to hear about how good it is to raise prices on goods that they buy all the time. They don’t really want to hear about how they’re going to have to pay more taxes. Just for the same reason that all of us don’t want to have our income lowered. We don’t like to take a pay cut. We don’t like to take a tax increase.

Rob Wiblin: But I’ve also heard this other line of research that the selfish voter hypothesis is kind of wrong, because voters very often take positions that are largely expressive about communicating their values, because their views and how they vote makes very little difference to the actual outcome. So if you enjoy saying, “It would be good for taxes to be higher,” then that can massively outweigh the downside of the tiny possibility that you saying that could actually cause taxes on you to be increased.

Rob Wiblin: You can get people to take, in politics or in voting, very idealistic positions that maybe if they’re actually implemented, they’ll be quite pissed off. But they’re willing to express views that would be very costly to them in some sense. Have you read that literature?

Matthew Yglesias: Yeah. I think it’s always interesting how much things tend to flip when it becomes more concrete in a lot of ways. The evolution of political polarization in most Western countries has come to be that educated people are on the left politically, even though oftentimes they’re reasonably affluent, which is just contrary to how politics has traditionally been organized. So they will espouse lots of tax-increasing ideas that are not necessarily in the interests of urban, young, cosmopolitan, professional-minded people. And yet it has been challenging to actually get those kinds of increases enacted.

Matthew Yglesias: One of the ways that the Democratic Party in the US has evolved over the years is that Barack Obama promised to raise taxes only on people earning over $250,000 a year. Then to get a measure through Congress, he had to raise that ceiling to $450,000 a year. Joe Biden took over the $450,000 baseline, but he has struggled to achieve even that, and is looking now at a very, very, very narrow kind of tax base. I do think that that’s because the influx of more affluent people into the Democratic Party has made it more challenging to actually raise taxes, even though there is a lot of support for this kind of symbolic egalitarianism, and in some ways more support than ever for being mean to billionaires and things like that.

Matthew Yglesias: I’m trying to think of some other examples that you have of this. It’s common to meet people who are very worried about the environment and sustainability, but then if you tell them that gas stoves are bad — this is common in America, at least, to have gas stoves — they’ll freak out, and be like, “That’s terrible,” because it’s so concrete. People here are not used to the high-quality electric induction stoves and the old-fashioned electric coil stoves, but of course they work and you can cook food. They’re not as good, and it’s a big yuppy lifestyle signifier to have a gas stove — it shows that you’ve made it. When you actually propose taking it away from people, they get very leery.

Matthew Yglesias: So New York just made a rule that new construction is not going to be allowed to have the gas hookups. But they made sure that if you have existing construction, it’s not only that you don’t have to give up your gas stove, but you’ll be able to replace it with another gas stove. They’re trying to thread the needle there. People want to take action, and they came up with a way so that the action will not accrue to the people who are actually voting right now. Politics is tough in that respect.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. The gas stove one is interesting, because it’s not only a global environmental concern, it’s also a health concern for the people in the house. It tends to cause a bit of respiratory problems for people to have gas stoves. It’s not so large that people tend to notice, but folks who have studied this have realized that it’s just bad for people’s health.

Matthew Yglesias: That may be the future — making a deterrent — because you could flip the script on that from “This is classy” to “You are indifferent to the lives of your children.”

Rob Wiblin: “Quit smoking.”

Matthew Yglesias: Yeah, exactly.

The influence of prior beliefs [01:05:53]

Rob Wiblin: I think some of what’s going on here is that I suspect that quite a lot of your reading of polling, and mine as well — how we interpret it — is very colored by priors that we have about what things people are likely to support and what things they probably won’t. When someone comes to me with polling saying that actually, a great majority of people support a carbon tax, I’m like, “No way, no way,” because I grew up in the debates about the carbon tax in Australia. I was in favor of it, but I could just see that the attack ads were really successful. People did not want to have their gas prices go up, and so I had this very strong prior that it’s going to be really hard in a real political campaign to get most people to vote in favor of a carbon tax that is going to substantially raise costs for them.

Rob Wiblin: Maybe I could be wrong about that, but I have all these perceptions about what can get through the political process and what can’t. I suppose people who have different priors about that could look at the same polling and come away with quite a different conclusion than what you or I might, because there’s just so many polls to choose from.

Matthew Yglesias: Yeah. I do think that that’s true. The other thing I will say is, this is something where I have seen a rapid evolution of conventional wisdom to positions that I think are wrong. That 15 years ago, everybody knew that raising the gas tax was unpopular, but also that it might be a good thing to do, and I could just say that in a story and people were like, “Yeah. No, that’s fine.”

Matthew Yglesias: Certain very specific progressive advocacy groups invested a fair amount of money in trying to convince people that their entire Democratic Party policy agenda is super popular, and it took real work to dislodge people from longstanding conventional wisdom. Because one group of people gets impatient with me because they’re like, “You’re being wrong, blah, blah, blah.” Another group of people gets impatient with me because they’re like, “Wait, everybody knows this.” And I’m much more on the side of “everybody knows this.”

Matthew Yglesias: I think that there was a fairly recent US-specific effort to create a bit of conventional wisdom that the American electorate really yearns for transformation into a European-style welfare state. That is not true, and most people have mostly been aware that it’s not true, and are sort of coming back to reality. I kind of hope to not spend the rest of my life writing and thinking about this subject, because I actually think it’s not that interesting.

Matthew Yglesias: You can see — if you do surveys on very abstract values about individualism, authority, religion, et cetera — that American public opinion is just somewhat to the right of European public opinion. Americans are more individualistic, they’re more religious, they’re more hierarchical. Not wildly so, there’s plenty of overlap, but discernibly. I think that’s what people have mostly thought from history. Maybe this is too wildly speculative, but I think there was a self-selection of more individualism-minded people to immigrate into the colonies and all of the settler states had lower taxes and stuff than the continent. I mean, I don’t know.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah, yeah, yeah. I do sometimes say to Europeans that it’s not surprising that Americans are more skeptical about government programs, because the government seems worse at delivering programs. Then sometimes people respond like, “Yeah, well that’s a deliberate scheme by people who don’t want the government to be doing more things, is to make it bad at doing things.” There’s people who are like that.

Matthew Yglesias: I mean, there’s definitely something to that, right?

Rob Wiblin: There’s some truth to that, yeah.

Matthew Yglesias: That’s an area that I find much more rewarding to think about and focus on: how can we improve programs, and make people like them better, and do something useful in life.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. I don’t know this group that’s been trying to persuade people that the progressive policy agenda was super popular all along. Although many of them probably do sincerely believe that, and they would probably respond that there has been polling to show that depending on how you frame things — if you ask the question the right way, if you present these policies with the benefits in mind — then it’s easier to persuade people to support them than you might have thought. There’s a lot of latent potential support that this polling is bringing up.

Matthew Yglesias: Yes. Though I think the best version of the argument is almost the opposite: when you put things in place, they tend to be fairly durable. So there’s something to be said for a YOLO attitude to this kind of thing. Barack Obama’s healthcare plan was not very popular when Congress enacted it, there was a significant backlash to it in 2010. But then, when there was an effort to remove it, there was a backlash to that.

Matthew Yglesias: So there’s a tension in US politics right now between that line of thinking: you know, Biden and the Democrats should get done what they can, while they can, and who cares what happens next. And this kind of, “An authoritarian Republican Party is poised to extinguish democracy” rhetoric. I think that a lot of people on the left have an unresolved tension in their views of what they’re saying. Because saying, “The opposition is really, really evil” — that’s a leftist stance. But saying, “We need to be incredibly bold with what we do” — that’s a leftist stance too. And then you could square the circle by saying, “Well, being really, really bold is going to be overwhelmingly popular,” and so that’s very attractive, right?

Matthew Yglesias: It just relieves dissonance. And I think, as is the case with a lot of attractive dissonance-reducing beliefs, it’s not very well supported empirically. And there’s a tough judgment call to be made about how risky do you really want policymakers to be? I was a kid when Bill Clinton was president; I was a teenager, so I was aware of what happened. I’ve always been interested in politics, and he was super duper popular — and he also didn’t have that much in the way of great achievements.

Matthew Yglesias: It seemed to me at the time that that was a pretty disappointing way to live your life and way to be doing politics, but it’s hard to argue with the results, right? People really loved that. That’s a style of politics that’s pretty attractive.

Loss aversion [01:12:19]

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. We talked about some general preconceptions that we have, or beliefs that we have about what kind of policies are popular and which ones aren’t. One is that people don’t like to pay more money if that’s really salient. I guess another one is just that there’s a certain fraction of people who just don’t like changing stuff. Are there any other design principles that you might want to always keep in mind when designing a policy about what kinds of things end up being popular and not popular?

Matthew Yglesias: I mean, I do think that it’s not just the status quo, but it’s risk aversion. People dwell on the downside and loss. I shouldn’t say risk aversion — it’s loss aversion: people are more worried about losing what they have than about gaining something that they don’t currently have. So it’s hard for people on the left to persuade people that some new program is going to be amazing and it’s going to be worth paying the taxes, but it’s also hard for people on the right to win arguments that are like, “Well, without this program, we can cut taxes and that’s going to create better incentives to save and invest, and that’s going to increase growth by 0.002%.” When you compound that out for X number of years, people get a lot of like, “Eh, I don’t know about that.”

Matthew Yglesias: People are also just not great at thinking about the long term. If you ask somebody who’s 40, “Do you care about what’s going to happen to you when you’re 70?” They’d be like, “Of course. I’m not a crazy person.” Now you ask them, do they care what’s going to happen hundreds of generations in the future, they might say no. We might say, “OK, you discount more than you should.” But even when they say that they’re not discounting the future of their own life, I think they just pretty clearly are when they’re making policy decisions.

Matthew Yglesias: People are not in the habit of really thinking about their long-term interests, and we see that in all kinds of behaviors. It’s why there’s people who smoke. It’s why lots of people struggle with all kinds of personal health issues. And in their political thinking, it’s even worse. To really get people to think, “How’s this going to play out?” — it’s tough.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. People talk a lot about means testing making policies more or less popular. So for people overseas, “means testing” I think is the term for whether you allow everyone to access a program, or only people who are below some income threshold.

Matthew Yglesias: Yeah. People argue about this a lot. I actually think if you pay attention to what everyone’s saying, they are not in that much of a tension really. If a program exists and everybody is using it, that makes it much, much harder to get rid of, versus a very narrow type of program — so there is a political durability benefit to some universalistic designs. At the same time, the broader you make the program, the more tax revenue you need to get.