Are too many people going into biomedical research – or too few?

Are too many people going into biomedical research or too few? As we explore in our new review of the career there are probably too many people entering the field. Biomedical research is a very promising way to make the world a better place if you have a high chance of being a top researcher, but for most people it’s a very tough road and entering could be a costly mistake. In the rest of the post, we’ll explain why and help you figure out whether it might be for you.

Biomedical research is a good path—if you’re a good fit.

We sometimes encounter people who might be a good fit for biomedical research, but who are skeptical about its potential impact. We think this might be misguided because:

- There are exciting areas of research that could offer enormous upside, such as anti-aging research, neural implants, gene therapy and synthetic biology.

Potentially very high returns to research with comparatively low costs. According to one estimate, the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease in the US in the 1970’s and 1980’s alone had $31 trillion of associated gains.1 This is on the order of 60 times as large as all spending on medical research over the period.2 Another analysis estimates that a 1% reduction in cancer mortality in the US would be worth $500 billion (in comparison, the current research budget is only around 5 billion).3

Constrained by good researchers. Senior researchers we’ve spoken to have told us that the difference between an average team member and a really good one is vast; in many cases they would be willing to turn down large amounts of money if it meant that they could add one excellent researcher to their project. For example:

“The best people are the biggest struggle. The funding isn’t a problem. It’s getting really special people. I call them the one percenters…If you have a good person, it’s easy to get the grants for them…One good guy can cover the ground of five, and I’m not exaggerating”

John Todd, Professor of Medical Genetics at Cambridge- Top researchers have a lot more impact than average. Some researchers publish scientific papers at a rate at least fifty times greater than others, and the distribution of research output appears to be log normal.4

Avoid entering the field if your chances of becoming a top researcher are low.

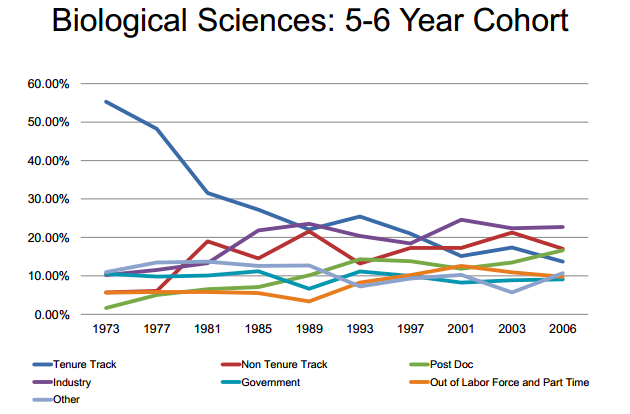

Most researchers don’t make it to tenured professor roles. In the US, the percentage of people with tenure track jobs five or six years after their PhD has been steadily falling:

Source: The Atlantic This trend is likely due to the increase in the number of PhDs being produced, without a corresponding increase in the number of tenure track positions.

Biomedical researchers can get pushed out even in their forties.

“It can leave people a bit stranded mid-career. You start out well, but you don’t quite make it to the top. You’re on a 3-5 year contract. You find it doesn’t get renewed. You’re 45 and stranded.” Prof. Sir Andrew McMichael

- Long time to train and relatively narrow exit options. It takes 10-12 years before you’re able to run a research program if you enter via medical school, or 6+ years if you enter by doing a PhD straight away. Most people who train end up having to leave the field, and many don’t build particularly transferable skills whilst in the path, leaving them with few good options.

Is this the right path for you?

Success in the field of biomedical research is hard to predict, but your chances are higher if:

- You have an undergraduate degree from a top university with high grades (the average GPA of those admitted to a biology PhD at MIT was 3.81 in 2014).5

- You’ve done a placement in a lab before your PhD and received highly positive feedback on your potential from your supervisor.

- You can get a place in a top-10 PhD program for your specialty. Average GRE scores for MIT in 2014 were Verbal (163; 89%), Quantitative (165; 88%), and Writing (4.8; 79%).6

- If you’ve done a PhD, you have several publications. First author on a Nature paper would be very good, second or third author on a Nature paper and lead author on a few others would be more common.

- You have knowledge of programming, maths or statistics (these skills are highly in-demand even if not required). One professor said: “The MD and programming/statistics combo is lethal. Top of the world. There’s major demand…All the kids need to learn to program and understand statistics [because] the data sets are getting bigger and better.”

- You are willing and able to be highly strategic in positioning yourself for career progression, not just excelling at research. Successful researchers optimise heavily around building strong collaborations to make it easier to get funding, publishing large numbers of papers in top journals and working at the most prestigious labs to establish their credentials.7

- You have intense intellectual curiosity for biomedical research that can sustain you through frequent setbacks.8

If this sounds like you, read our in-depth profile.

Use our career quiz to get recommendations of alternatives to biomedical research.

Notes and references

- “Increases in life expectancy in just the decades of the 1970’s and 1980’s were worth $57 trillion to Americans – a figure six times larger than the entire output of tangible good and services last year. The gains associated with the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease alone totaled $31 trillion.” Exceptional Returns: The Economic Value of America’s Investment in Medical Research↩

- “Murphy and Topel estimate that the total economic value to Americans of reductions in mortality from cardiovascular disease averaged $1.5 trillion annually in the 1970-1990 period. So if just one-third of the gain came from medical research, the return on the investment averaged $500 billion

a year. That’s on the order of 20 times as large as average annual spending on medical research – by any benchmark an astonishing return for the investment.” Exceptional Returns: The Economic Value of America’s Investment in Medical Research↩ - Estimates of Funding for Various Research, Condition, and Disease Categories↩

- Shockley, William. “On the statistics of individual variations of productivity in research laboratories.” Proceedings of the IRE 45.3 (1957): 279-290.↩

- MIT Department of Biology: Prospective Students↩

- MIT Department of Biology: Prospective Students↩

- “…you want to go to the best labs in your general area – neuroscience, immunology, cancer, cell biology. You just need to go where the best science is – the most Nature papers, the most Cell papers.” (Interview with Prof. Sir Andrew McMichael, leading HIV vaccine researcher) “Get into a really really good lab (in a major centre). (e.g. LMB in Cambridge) Then work on a really difficult important problem for 10 years. Try to get long-term funding…To get the first step, you’ll need to initially focus on publishing in a couple of top journals. There’s a lot of hard work and luck involved; always be asking the question, if I get the answer to my big question, how many people in the world will care?” (Interview with Prof. Todd, a Cambridge Professor of Medical Genetics)↩

- For example, Dr Ewer said: “Unless you have an absolute obsession with your subject, it’s very hard to persevere and not become demoralized.”↩