Beyond human minds: The bewildering frontier of consciousness in insects, AI, and more

Beyond human minds: The bewildering frontier of consciousness in insects, AI, and more

By The 80,000 Hours podcast team · Published May 23rd, 2025

On this page:

- Introduction

- 1 Transcript

- 1.1 Cold open [00:00:00]

- 1.2 Luisa's intro [00:00:57]

- 1.3 Robert Long on what we should picture when we think about artificial sentience [00:02:49]

- 1.4 Jeff Sebo on what the threshold is for AI systems meriting moral consideration [00:07:22]

- 1.5 Meghan Barrett on the evolutionary argument for insect sentience [00:11:24]

- 1.6 Andrés Jiménez Zorrilla on whether there's something it's like to be a shrimp [00:15:09]

- 1.7 Jonathan Birch on the cautionary tale of newborn pain [00:21:53]

- 1.8 David Chalmers on why artificial consciousness is possible [00:26:12]

- 1.9 Holden Karnofsky on how we'll see digital people as... people [00:32:18]

- 1.10 Jeff Sebo on grappling with our biases and ignorance when thinking about sentience [00:38:59]

- 1.11 Bob Fischer on how to think about the moral weight of a chicken [00:49:37]

- 1.12 Cameron Meyer Shorb on the range of suffering in wild animals [01:01:41]

- 1.13 Sébastien Moro on whether fish are conscious or sentient [01:11:17]

- 1.14 David Chalmers on when to start worrying about artificial consciousness [01:16:36]

- 1.15 Robert Long on how we might stumble into causing AI systems enormous suffering [01:21:04]

- 1.16 Jonathan Birch on how we might accidentally create artificial sentience [01:26:13]

- 1.17 Anil Seth on which parts of the brain are required for consciousness [01:32:33]

- 1.18 Peter Godfrey-Smith on uploads of ourselves [01:44:47]

- 1.19 Jonathan Birch on treading lightly around the "edge cases" of sentience [02:00:12]

- 1.20 Meghan Barrett on whether brain size and sentience are related [02:05:25]

- 1.21 Lewis Bollard on how animal advocacy has changed in response to sentience studies [02:12:01]

- 1.22 Bob Fischer on using proxies to determine sentience [02:22:27]

- 1.23 Cameron Meyer Shorb on how we can practically study wild animals' subjective experiences [02:26:28]

- 1.24 Jeff Sebo on the problem of false positives in assessing artificial sentience [02:33:16]

- 1.25 Stuart Russell on the moral rights of AIs [02:38:31]

- 1.26 Buck Shlegeris on whether AI control strategies make humans the bad guys [02:41:50]

- 1.27 Meghan Barrett on why she can't be totally confident about insect sentience [02:47:12]

- 1.28 Bob Fischer on what surprised him most about the findings of the Moral Weight Project [02:58:30]

- 1.29 Jeff Sebo on why we're likely to sleepwalk into causing massive amounts of suffering in AI systems [03:02:46]

- 1.30 Will MacAskill on the rights of future digital beings [03:05:29]

- 1.31 Carl Shulman on sharing the world with digital minds [03:19:25]

- 1.32 Luisa's outro [03:33:43]

- 2 Learn more

- 3 Related episodes

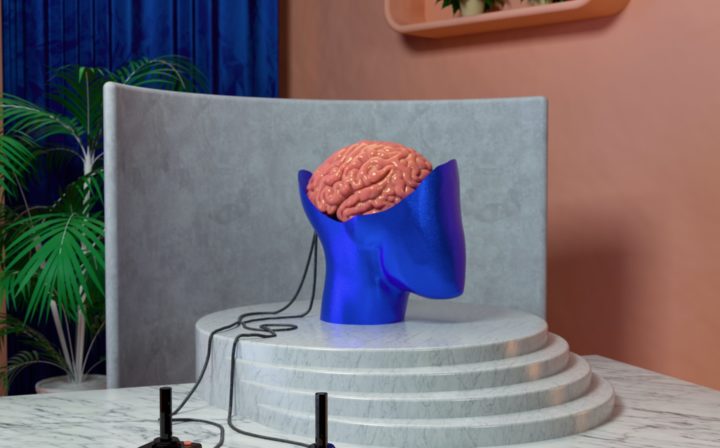

What if there’s something it’s like to be a shrimp — or a chatbot?

For centuries, humans have debated the nature of consciousness, often placing ourselves at the very top. But what about the minds of others — both the animals we share this planet with and the artificial intelligences we’re creating?

We’ve pulled together clips from past conversations with researchers and philosophers who’ve spent years trying to make sense of animal consciousness, artificial sentience, and moral consideration under deep uncertainty.

You’ll hear from:

- Robert Long on how we might accidentally create artificial sentience (from episode #146)

- Jeff Sebo on when we should extend extend moral consideration to digital beings — and what that would even look like (#173)

- Jonathan Birch on what we should learn from the cautionary tale of newborn pain, and other “edge cases” of sentience (#196)

- Andrés Jiménez Zorrilla on what it’s like to be a shrimp (80k After Hours)

- Meghan Barrett on challenging our assumptions about insects’ experiences (#198)

- David Chalmers on why artificial consciousness is entirely possible (#67)

- Holden Karnofsky on how we’ll see digital people as… people (#109)

- Sébastien Moro on the surprising sophistication of fish cognition and behaviour (#205)

- Bob Fischer on how to compare the moral weight of a chicken to that of a human (#182)

- Cameron Meyer Shorb on the vast scale of potential wild animal suffering (#210)

- Lewis Bollard on how animal advocacy has evolved in response to sentience research (#185)

- Anil Seth on the neuroscientific theories of consciousness (#206)

- Peter Godfrey-Smith on whether we could upload ourselves to machines (#203)

- Buck Shlegeris on whether AI control strategies make humans the bad guys (#214)

- Stuart Russell on the moral rights of AI systems (#80)

- Will MacAskill on how to integrate digital beings into society (#213)

- Carl Shulman on collaboratively sharing the world with digital minds (#191)

Audio engineering: Ben Cordell, Milo McGuire, Simon Monsour, and Dominic Armstrong

Additional content editing: Katy Moore and Milo McGuire

Transcriptions and web: Katy Moore

Transcript

Table of Contents

- 1 Cold open [00:00:00]

- 2 Luisa’s intro [00:00:57]

- 3 Robert Long on what we should picture when we think about artificial sentience [00:02:49]

- 4 Jeff Sebo on what the threshold is for AI systems meriting moral consideration [00:07:22]

- 5 Meghan Barrett on the evolutionary argument for insect sentience [00:11:24]

- 6 Andrés Jiménez Zorrilla on whether there’s something it’s like to be a shrimp [00:15:09]

- 7 Jonathan Birch on the cautionary tale of newborn pain [00:21:53]

- 8 David Chalmers on why artificial consciousness is possible [00:26:12]

- 9 Holden Karnofsky on how we’ll see digital people as… people [00:32:18]

- 10 Jeff Sebo on grappling with our biases and ignorance when thinking about sentience [00:38:59]

- 11 Bob Fischer on how to think about the moral weight of a chicken [00:49:37]

- 12 Cameron Meyer Shorb on the range of suffering in wild animals [01:01:41]

- 13 Sébastien Moro on whether fish are conscious or sentient [01:11:17]

- 14 David Chalmers on when to start worrying about artificial consciousness [01:16:36]

- 15 Robert Long on how we might stumble into causing AI systems enormous suffering [01:21:04]

- 16 Jonathan Birch on how we might accidentally create artificial sentience [01:26:13]

- 17 Anil Seth on which parts of the brain are required for consciousness [01:32:33]

- 18 Peter Godfrey-Smith on uploads of ourselves [01:44:47]

- 19 Jonathan Birch on treading lightly around the “edge cases” of sentience [02:00:12]

- 20 Meghan Barrett on whether brain size and sentience are related [02:05:25]

- 21 Lewis Bollard on how animal advocacy has changed in response to sentience studies [02:12:01]

- 22 Bob Fischer on using proxies to determine sentience [02:22:27]

- 23 Cameron Meyer Shorb on how we can practically study wild animals’ subjective experiences [02:26:28]

- 24 Jeff Sebo on the problem of false positives in assessing artificial sentience [02:33:16]

- 25 Stuart Russell on the moral rights of AIs [02:38:31]

- 26 Buck Shlegeris on whether AI control strategies make humans the bad guys [02:41:50]

- 27 Meghan Barrett on why she can’t be totally confident about insect sentience [02:47:12]

- 28 Bob Fischer on what surprised him most about the findings of the Moral Weight Project [02:58:30]

- 29 Jeff Sebo on why we’re likely to sleepwalk into causing massive amounts of suffering in AI systems [03:02:46]

- 30 Will MacAskill on the rights of future digital beings [03:05:29]

- 31 Carl Shulman on sharing the world with digital minds [03:19:25]

- 32 Luisa’s outro [03:33:43]

Cold open [00:00:00]

Meghan Barrett: The reason I am not giving you a sentience score is the error bars are so large right now that it’s almost a meaningless number. Because I’m waiting on so much evidence. So much evidence. So I think that’s really an essential feature of it for me.

The second thing is that I worry especially as an expert that that number would be overemphasised, that somebody would inevitably put into a spreadsheet, and they would use that spreadsheet to make all kinds of decisions. And that number does not reflect the complexity that you and I have now spent three hours discussing, and barely scratched the surface of. I want to talk about the complexity and the nuance, and a number does not demonstrate that.s

I think it’s important also that we understand that if you have updated at all towards insects plausibly being sentient, scale takes the rest of the issue for you to a serious place. There are so, so, so many of them that if you take it seriously at all, then you need to be thinking that this is an issue to work on.

Luisa’s intro [00:00:57]

Luisa Rodriguez: Hey listeners, Luisa here. You were just listening to Meghan Barrett, an insect neurobiologist whose mind-blowing facts about insects really opened my eyes about the likelihood of invertebrate sentience when I interviewed her last year.

We’re back today with another compilation of our favourite bits from past shows — this time on a topic that listeners might know I’m absolutely captivated by: consciousness and sentience in nonhuman minds, including digital ones.

Over the last few years, this area of study has really taken off, and many of the guests you’ll hear in this episode are pioneers in their fields. Whether they’re entomologists, philosophers, machine learning researchers, or neuroscientists, they’re all studying angles on slippery questions like what consciousness is (even in humans!), how we’d recognise it in minds unlike our own, and how much we should worry about other beings’ ability to experience pleasure and pain.

You’ll hear from:

- David Chalmers on why artificial consciousness is possible

- Jeff Sebo on what the threshold is for AI systems meriting moral consideration

- Jonathan Birch on how we very recently thought newborns couldn’t feel pain, and how we’re likely making similar mistakes today

- Robert Long on how we might stumble into causing enormous suffering for digital minds

- Meghan Barrett on the evolutionary origins of consciousness and sentience, and whether brain size and sentience are related

- Plus many more!

You also may have noticed that this is a pretty long episode. We decided not to cut it down more, given that this issue is important, and long episodes on this topic haven’t deterred listeners in the past… on the contrary, our 4 hour and 40 minute marathon session with David Chalmers was one of our most popular episodes!

All right, I hope you enjoy!

Robert Long on what we should picture when we think about artificial sentience [00:02:49]

From episode #146 – Robert Long on why large language models like GPT (probably) aren’t conscious

Luisa Rodriguez: I basically don’t feel like I have a great sense of what artificial sentience would even look like. Can you help me get a picture of what we’re talking about here?

Robert Long: Yeah. I mean, I think it’s absolutely fine and correct to not know what it would look like. In terms of what we’re talking about, I think the short answer, or a short hook into it, is just to think about the problem of animal sentience. I think that’s structurally very similar.

So, we share the world with a lot of nonhuman animals, and they look a lot different than we do, they act a lot differently than we do. They’re somewhat similar to us. We’re made of the same stuff, they have brains. But we often face this question of, as we’re looking at a bee going through the field, like we can tell that it’s doing intelligent behaviour, but we also wonder, is there something it’s like to be that bee? And if so, what are its experiences like? And what would that entail for how we should treat bees, or try to share the world with bees?

I think the general problem of AI sentience is that question, and also harder. So I’m thinking of it in terms of this kind of new class of intelligent or intelligent-seeming complex systems. And in addition to wondering what they’re able to do and how they do it, we can also wonder if there is, or will ever be, something that it’s like to be them, and if they’ll have experiences, if they’ll have something like pain or pleasure. It’s a natural question to occur to people, and it’s occurred to me, and I’ve been trying to work on it in the past couple of years.

Luisa Rodriguez: I guess I have an almost even more basic question, which is like, when we talk about AI sentience — both in the short term and in the long term — are we talking about like a thing that looks like my laptop, that has like a code on it, that has been coded to have some kind of feelings or experience?

Robert Long: Yeah, sure. I use the term “artificial sentience.” Very generally, it’s just like things that are made out of different stuff than us — in particular, silicon and the computational hardware that we run these things on — could things built out of that and running computations on that have experiences?

So the most straightforward case to imagine would probably be a robot — because there, you can kind of clearly think about what the physical system is that you’re trying to ask if it’s sentient.

Things are more complicated with the more disembodied AI systems of today, like ChatGPT — because there, it’s like a virtual agent in a certain sense. And brain emulations would also be like virtual agents. But I think for all of those, you can ask, at some level of description or some way of carving up the system, “Is there any kind of subjective experience here? Is there consciousness here? Is there sentience here?”

Luisa Rodriguez: Yeah, cool. I guess the reason I’m asking is because for a long time I’ve had this sense that when people use the term “digital minds” or “artificial sentience,” I have like some vague images that kind of come from sci-fi, but I mostly feel like I don’t even know what we’re talking about. But it sounds like it could just look like a bunch of different things, and the core of it is something that is sentient — in maybe a way similar, maybe a way that’s pretty different to humans — but that exists not in biological form, but in some grouping that’s made up of silicon. Is that basically right?

Robert Long: Yeah. And I should say, I guess silicon is not that deep here. But yeah, something having to do with running on computers, running on GPUs. I’m sure I could slice and dice it, and you could get into all sorts of philosophical-like classification terms for things. But yeah, that’s the general thing I’m pointing at.

And I in particular have been working on the question of AI systems. The questions about whole brain emulations I think would be different, because we would have something that at some level of description is extremely similar to the human brain by definition. And then you could wonder about whether it matters that it’s an emulated brain, and people have wondered about that.

In the case of AIs, it’s even harder — because not only are they made on different stuff and maybe somewhat virtual, they also are kind of strange and not necessarily working along the same principles as the human brain.

Jeff Sebo on what the threshold is for AI systems meriting moral consideration [00:07:22]

From episode #173 – Jeff Sebo on digital minds, and how to avoid sleepwalking into a major moral catastrophe

Jeff Sebo: The general case for extending moral consideration to AI systems is that they might be conscious or sentient or agential or otherwise significant. And if they might have those features, then we should extend them at least some moral consideration in the spirit of caution and humility.

So the standard should not be, “Do they definitely matter?” and it should also not be, “Do they probably matter?” It should be, “Is there a reasonable, non-negligible chance that they matter, given the information available?” And once we clarify that that is the bar for moral inclusion, then it becomes much less obvious that AI systems will not be passing that bar anytime soon.

Luisa Rodriguez: Yeah, I feel kind of confused about how to think about that bar, where I think you’re using the term “non-negligible chance.” I’m curious: What is a negligible chance? Where is the line? At what point is something non-negligible?

Jeff Sebo: Yeah, this is a perfectly reasonable question. This is somewhat of a term of art in philosophy and decision theory. And we might not be able to very precisely or reliably say exactly where the threshold is between non-negligible risks and negligible risks — but what we can say, as a starting point, is that a risk can be quite low; the probability of harm can be quite low, and it can still be worthy of some consideration.

For example: why is driving drunk wrong? Not because it will definitely kill someone. Not even because it will probably kill someone. It might have only a 1-in-100 or 1-in-1,000 chance of killing someone. But if driving drunk has a 1-in-100 or 1-in-1,000 chance of killing someone against their will unnecessarily, that can be reason enough to get an Uber or a Lyft, or stay where I am and sober up. It at least merits consideration, and it can even in some situations be decisive. So as a starting point, we can simply acknowledge that in some cases a risk can be as low as one in 100 or one in 1,000, and it can still merit consideration.

Luisa Rodriguez: Right. It does seem totally clear and good that regularly in our daily lives we consider small risks of big things that might be either very good or very bad. And we think that’s just clearly worth doing and sensible. Sometimes probably, in personal experience, I may not do it as much as I should — but on reflection, I certainly endorse it.

So I guess the thinking here is that, given that there’s the potential for many, many, many beings with a potential for sentience, albeit some small likelihood, it’s kind of at that point that we might start wanting to give them moral consideration. Do you want to say exactly what moral consideration is warranted at that point?

Jeff Sebo: This is a really good question, and it actually breaks down into multiple questions.

One is a question about moral weight. We already have a sense that we should give different moral weights to beings with different welfare capacities: If an elephant can suffer much more than an ant, then the elephant should get priority over the ant to that degree. Should we also give more moral weight to beings who are more likely to matter in the first place? If an elephant is 90% likely to matter and an ant is 10% likely to matter, should I also give the elephant more weight for that reason?

And then another question is what these beings might even want and need in the first place. What would it actually mean to treat an AI system well if they were sentient or otherwise morally significant? That question is going to be very difficult to answer.

So there are no immediate implications to the idea that we should give some moral consideration to AI systems if they have a non-negligible chance of being sentient. All that it means is that we should give them at least some weight when making decisions that affect them, and then we might disagree about how much weight and what follows from that.

Meghan Barrett on the evolutionary argument for insect sentience [00:11:24]

From episode #198 – Meghan Barrett on challenging our assumptions about insects

Meghan Barrett: Importantly, I think another fact that a lot of people don’t realise from this evolutionary perspective is that insects are thus actually most closely related to crustaceans. They form this group together called the pancrustacea, and that group shares a common ancestor.

So I think that’s something else that people should consider. If you’re somebody who takes crustacean sentience seriously, and sentience is a trait that has evolved — it didn’t just appear in organisms as they are today, which I’m sure will be something we repeatedly touch on throughout this episode — if you’re somebody who believes that crustaceans are given the benefit of the doubt for you, for sentience, then you might also think that insects are worth giving the benefit of the doubt for some reasons as well, from an evolutionary perspective.

And there are two possible hypotheses you could entertain here. One is the idea that sentience evolved exactly one time — and so everybody descended from that common ancestor, unless maybe they lost it for some reason, has that characteristic. So if you accept both vertebrates and any of the inverts — so a cephalopod or a decapod — if you’re convinced on a single invertebrate and you also are convinced on a single origin point for this, you have a problem, right? Because the closest common ancestor to all of those folks is very far back.

And so you’re going to have all your insects, all your nematodes, all your decapods, all your annelids (which are another kind of worm) included, if you believe that there’s one common ancestor and no loss events. Now, maybe you think there’s loss events, but now you’re talking about multiple loss events, because there’s so many invertebrates. So you’re going to have to justify each of those losses, which you could potentially do.

Another possible hypothesis is that sentience evolved multiple times independently in different groups. I would probably say this is more plausible in my view, in part because we see multiple emergence of things all the time in evolutionary history.

Vision is a great example: we know that eyes might have evolved as many as 40 times during animal evolutionary history. And then, when we think about the development of eyes, it’s crucial to consider how they all generate the same basic function of being able to see something, even though they may vary in a lot of ways structurally.

For instance, we saw the multiple emergence of what we call these crystalline lenses in the eyes of animals: some were made from co-opting calcite, others were made by co-opting heat shock proteins, still others were made by co-opting other novel proteins. All of them make these crystalline lenses, right? Or you could consider that independent but convergent evolution of similar structures in vertebrate eyes and spider eyes — and that can result in, again, the same basic capacity to see something.

Of course, then we can talk about how the exact functions of seeing using these different structures or similar structures can vary. You know, acuity can vary, or wavelengths that the animal can sense can vary. But still, we think that the same basic capacity of some kind of sight is there for all of these animals.

This is all to say that it makes it more complicated if we’re looking for something like consciousness. So the function we’re interested in is consciousness instead of vision. Now we’re saying that if there’s more than one origin point, we need to be looking for potentially divergent structures capable of producing that common basic function. And of course, that common basic function can have lots of variance and gradation. And we don’t even have a good grasp yet on human consciousness, so you can see how acknowledging the possibility of multiple independent origins would then make this all very challenging to figure out.

But in any case, I think when you look at this from an evolutionary perspective, it’s important to consider who’s a close relative? Who are your common ancestors for that group? When you think these characteristics evolved, why do you think they evolved there? And then, if you’re somebody who takes crustaceans seriously, given that their close relation is the insects, you’re going to need to seriously consider the hexapods too.

Andrés Jiménez Zorrilla on whether there’s something it’s like to be a shrimp [00:15:09]

From 80k After Hours: Andrés Jiménez Zorrilla on the Shrimp Welfare Project

Rob Wiblin: How do shrimp farmers feel about their shrimp? Do they naturally care about their wellbeing, or see them as moral patients that can suffer?

Andrés Jiménez Zorrilla: That’s something that surprised us. When we did a survey in India, it’s a small sample, but we asked whether they felt that their shrimps could feel pain and stress, and 95% of them said yes. One of them actually had a very endearing answer saying that he spent more time with his animals than he did with his family and that, if his friends suffered, he said, “I also suffer.”

It’s very interesting. On the other hand, I think it’s unsurprising, because these people spend a significant amount of time seeing the behaviour of the animals. They’re much less skewed than consumers, who never see them alive. I’m almost betting that you or your audience have very rarely ever seen an image of a shrimp that’s alive and swimming. Most of them will have just seen them in cocktails. And these farmers just see them all the time. They see them when they’re sick. They see them when they’re feeding, when they’re swimming about — so they really care about them.

Rob Wiblin: I see. So they’re exposed and seeing shrimp all the time. It sounds like their behaviour is moderately complicated, that they’re doing interesting things that make them seem smart enough and reactive and responsive enough to circumstances that it’s very natural to feel that they can suffer or experience pleasure the same way that dogs or pigs do.

Andrés Jiménez Zorrilla: Exactly. I couldn’t have put it better. It’s very difficult to see them in farms, because the water in which they’re raised typically has high turbidity — it’s very murky. But once you actually see them — sometimes in tanks and in trade conferences and things like that — when they’re fed, they swim, they catch their feed, they take it to a little corner where each of them can eat it in peace. It’s very rare to see them behaving. There’s good research ongoing to understand behavioural issues of shrimps. It’s underway.

Rob Wiblin: I see. So they’re perhaps more like crabs or lobsters or octopus even than one might imagine, in terms of just how their behaviour looks.

Andrés Jiménez Zorrilla: Exactly. That was the argument that the scientists at the London School of Economics made when they wrote this paper for the UK sentience bill recently, in November last year. They did a full review of the evidence of sentience of cephalopod mollusks and decapods, which are exactly the ones that you mentioned.

What they found out is that, for those species that have been extensively researched, there is very good evidence that they’re sentient. What they say is the evidence in some other species is not as strong, but it’s only because they haven’t been researched for sentience purposes as much as other species — like, for example, crabs and octopuses, as you said.

Rob Wiblin: What sort of criteria are they using? When they study a species to try to figure out whether it’s sentient, what sort of things are they looking at to try to reach an evaluation?

Andrés Jiménez Zorrilla: That’s a good point, because it’s very difficult to have a smoking gun that tells you that an animal is sentient.

So in this specific case, what they did is they looked at eight different indicators of sentience. Those included whether they had nociceptors, so the right body parts to detect noxious stimuli; whether they had protective behaviours, adaptive behaviours, if anaesthesia was applied to certain body parts — whether their reaction changed, which would indicate that it’s not a reflex. Things like that.

Then they ranked whether the evidence was very high, high, to moderately low, et cetera, for each individual species. Then they came up with an overall assessment that all cephalopods and decapods should be protected by UK animal welfare law, and eventually they did. This was a report that was commissioned by the UK government to the London School of Economics. It was very independent research.

Rob Wiblin: OK, so shrimp respond to injuries. They probably learn from negative experiences that they have. Did they respond to anaesthetic? I know that’s one of the tests that people sometimes use.

Andrés Jiménez Zorrilla: There’s a paper that shows the responses that different decapods have to anaesthetics, as you said. With shrimps in particular, what they do is they pinch one of the antennas. They see how they behave: they flick their tails, they jump out of the water, et cetera. And then in the second stage, they apply anaesthetics and repeat the experiment, and the behaviour changes significantly. The time that they rub their little antenna is much, much lower. They probably swim normally, quicker, and things like that.

Rob Wiblin: I see. They are tending to injuries, and they tend to them less when they’re given anaesthetic. As an aside, it’s remarkable to me that anaesthetics that we’ve presumably developed for humans also work on shrimp. They’re so far away in the phylogenetic tree of life, and yet so much of the basic machinery of feeling seems to be similar enough.

Andrés Jiménez Zorrilla: That’s true. One of the arguments that some people made used to be that opioids don’t necessarily work the same in some of the animals. As you’ve said, not necessarily all of the anaesthetics need to work the same. But researchers have found anaesthetics that do apply and do have an effect on animals, and it changes behaviour.

Rob Wiblin: An audience member was curious to know: do you feel viscerally motivated by the prospect of shrimp suffering, or is your interest and motivation somewhat more on the intellectual side?

Andrés Jiménez Zorrilla: So until very recently, my response would’ve been completely on the intellectual side. It was not until I visited farms. I think most of us during our lifetimes will never visit a shrimp farm, or most people in the world will not visit a shrimp farm or see a shrimp being taken out of the water.

But when my cofounder, our programme director in India, and myself went to see what is called “harvesting” — which is the moment in which the animals are scooped out of the water and eventually put in crates and things like that — that process made me also viscerally care about this issue. But it definitely came through the more intellectual part.

Jonathan Birch on the cautionary tale of newborn pain [00:21:53]

From episode #196 – Jonathan Birch on the edge cases of sentience and why they matter

Luisa Rodriguez: Let’s turn to another edge case of sentience in humans: foetuses. You start this section of the book with what you call “the cautionary tale of newborn pain.” Can you talk me through that case?

Jonathan Birch: It’s another case I found unbelievable: in the 1980s, it was still apparently common to perform surgery on newborn babies without anaesthetic on both sides of the Atlantic. This led to appalling cases, and to public outcry, and to campaigns to change clinical practice. There was a public campaign led by someone called Jill Lawson, whose baby son had been operated on in this way and had died.

And at the same time, evidence was being gathered to bear on the questions by some pretty courageous scientists, I would say. They got very heavily attacked for doing this work, but they knew evidence was needed to change clinical practice. And they showed that, if this protocol is done, there were massive stress responses in the baby, massive stress responses that reduce the chances of survival and lead to long-term developmental damage. So as soon as they looked for evidence, the evidence showed that this practice was completely indefensible and then the clinical practice was changed.

So, in a way, people don’t need convincing anymore that we should take newborn human babies seriously as sentience candidates. But the tale is a useful cautionary tale, because it shows you how deep that overconfidence can run and how problematic it can be. It just underlines this point that overconfidence about sentience is everywhere and is dangerous.

Luisa Rodriguez: Yeah, it really does. I’m sure that had I lived in a different time, I’d at least have been much more susceptible to this particular mistake. But from where I’m standing now, it’s impossible for me to imagine thinking that newborns don’t feel pain, and therefore you can do massively invasive surgery on them without anaesthetic.

Jonathan Birch: It’s a hard one to believe, isn’t it? Of course, the consideration was sometimes made that anaesthesia has risks — and of course it does, but operating without anaesthesia also has risks. So there was real naivete about how the surgeons here were thinking about risk. And it’s what philosophers of science sometimes called the “epistemology of ignorance”: they were worried about the risks of anaesthesia, which is their job to worry about that, so they just neglected the risks on the other side. That’s the truly unbelievable thing.

Luisa Rodriguez: So the clinical updates that have happened since: my sense is that now it is standard procedure to give newborns anaesthetic during surgeries, and that the benefits outweigh the risks. You argue that that wasn’t inevitable. What’s the case for that?

Jonathan Birch: I think the public outcry also mattered. Clinical norms are very hard to shift. If it was really just these two people, Anand and Hickey, against the medical establishment, that’s not really how change happens. You know, we talk about theories of change sometimes — and “just get the evidence and take it to the establishment” is not a good theory of change. I think in this case, the fact that there was at the same time a powerful public campaign going on based on these horrible stories, that is why clinical practice got changed very quickly.

Luisa Rodriguez: So there’s a lesson there. I mean, there’s really nothing to say, but that that’s horrific, and important to know it happened, because we may be doing it again.

David Chalmers on why artificial consciousness is possible [00:26:12]

From episode #67 – David Chalmers on the nature and ethics of consciousness

David Chalmers: Some people think that no silicon-based computational system could be conscious because biology is required. I’m inclined to reject views like that, and there’s nothing special about the biology here.

One way to think about that is to think about cases of gradual uploading: you replace your neurons one at a time by silicon chips that play the same role. I think cases like this make it particularly hard to say that, if you say that the system at the other end is not conscious, then you have to say that consciousness either gradually fades out or during this process or it suddenly disappears during this process.

I think it’s at least difficult to maintain either of those lines. You could take the line that maybe silicon will never even be able to simulate biological neurons very well, even in terms of its effects. Maybe there’s some special dynamic properties that biology has that silicon could never have. I think that would be very surprising, because it looks like all the laws of physics we know about right now are computational. Roger Penrose has entertained the idea that’s false.

But if we assume that physics is computational, that one can in principle simulate the action of a physical system, then one ought to at least be able to create one of these gradual uploading processes and then someone who denies that the system on the other end could be conscious is going to have to say either it fades out in a really weird way during this process. You go through half consciousness, quarter consciousness, while your behaviour stays the same, or that it suddenly disappears at some point. You replace the magic neuron and it disappears.

Those are arguments I gave years ago now for why I think a silicon duplicated device can be conscious in principle.

Arden Koehler: I think I see why the sudden disappearance of consciousness in that scenario seems implausible. It’s like, “Well, what’s so special about that magic neuron?” But I don’t immediately see why the gradual fadeout of consciousness isn’t a reasonable possibility to entertain there?

David Chalmers: How are you thinking the gradual fadeout would go? First, we’d lose visual consciousness, then we’d lose auditory consciousness? Or…?

Arden Koehler: I don’t know exactly how it would go, but if we assume that consciousness can come in degrees, then why can’t it disappear in degrees?

David Chalmers: Yeah, I guess I’m thinking that I just put some crude measure on a state of consciousness. Like the number of bits involved in your state of consciousness. One way of imagining it fading is somehow lowering in intensity and then suddenly the intensity goes to zero and it all disappears.

That to me sounds like a version of sudden disappearance because the bits which still go from being a million bits to zero bits all at once. Strange in the way that sudden disappearance is strange. Maybe looking more continuous then somehow the number of bits in your consciousness has to gradually decrease. You go from a million bits to 100,000 to 10,000 to whatever.

And how would this work? Maybe my visual field would gradually lose distinctions, will gradually become more coarse-grained, maybe bits of it would disappear. Maybe one modality would go and then another modality.

But anyway, you’re going to have these weird intermediate states where you say the system is conscious, is saying it is fully conscious of all these things because its behaviour is the same, “I am visually conscious in full detail, I’m auditorily conscious.” In fact, their consciousness state is going to be a very, very pale reflection of the conscious state they’re talking about with very few, say bits, of consciousness.

That situation is the one that strikes me as especially strange. A conscious being that appears to be fully rational and believes it’s in this fully conscious state, but in fact, it’s in a very, very limited conscious state. If you’re an illusionist, you might think this kind of thing happens to you all the time.

Rob Wiblin: I think this is totally wrong. It seems like you could have a view where there’s information processing going on in the transmission between the neurons and that’s what’s generating the behaviour. But then there’s some other secret sauce that’s happening in the brain that we don’t understand and that we would not then replicate on the silicon chips.

As you go replacing each neuron and each synapse with the machine version of it, the information processing continues as before and the behaviour remains the same. But you’ve lost the part that was generating the consciousness; you haven’t engineered that into the computer components, and so just gradually the consciousness disappears.

David Chalmers: I can imagine this is at least conceivable, but then what are you going to say about the intermediate cases? There will have to be cases where the being is conscious and just massively wrong about its own consciousness. It says you’re not having experiences of red and green and orange right now. The fact is that it’s having a uniform gray visual field or thing like that.

Rob Wiblin: It seems possible, right?

Arden Koehler: I guess I also don’t find it as implausible as you seem to, Dave, that we could be wrong about our conscious experience or how much conscious experience we’re having in this gradual uploading example.

David Chalmers: That’s fair, and there certainly are many cases where people are very wrong about their own conscious experiences. Certainly, there are all kinds of pathologies where there’s blindness denial — where people say they’re having all kinds of visual experiences when it appears that they’re blind and they’re not having them. Maybe it could be like this. This is strange because functionally the system doesn’t seem to have any pathologies.

Anyway, I do allow that this is conceivable and I certainly can’t prove that it couldn’t happen. The more open you are to beings being very, very wrong about their consciousness, maybe you’ll be more open to this case.

Here’s one thing I’ll say, at the very least: if this actually happens, and we go through it and our behavior is the same throughout, then we have beings whose heads are first a quarter silicon, then a half silicon as well. They say, “Everything is fine, everything is fine, my conscious experience is exactly the way it was.” They’re telling us this, they’re talking to us. They update every week with a bit more silicon and we keep talking to them.

We are going to be very nearly completely convinced that they are conscious throughout. It’s going to become impossible to deny it. So at least as a matter of sociology, I think this view is likely to become the obvious-seeming view.

Holden Karnofsky on how we’ll see digital people as… people [00:32:18]

From episode #109 – Holden Karnofsky on the most important century

Rob Wiblin: Let’s talk about these digital people. What do you mean by digital people?

Holden Karnofsky: So the basic idea of a digital person is like a digital simulation of a person. It’s really like if you just take one of these video games, like The Sims, or… I use the example of a football game because I was able to get these different pictures of this football player, Jerry Rice, because every year they put out a new Madden video game. So, Jerry Rice looks a little more realistic every year. You have these video game simulations of people, and if you just imagine it getting more and more realistic until you have a perfect simulation.

So imagine a video game that has a character called Holden, and just does everything exactly how Holden would in response to whatever happens. That’s it. That’s what a digital person is. So it’s a fairly simple idea. In some ways it’s a very far-out extrapolation of stuff we’re already doing, which is we’re already simulating these characters.

Rob Wiblin: I guess that’d be one way to look at it. The way I’ve usually heard it discussed or introduced is the idea that, well, we have these brains and they’re doing calculations, and couldn’t we eventually figure out how to basically do all of the same calculations that the brain is doing in a simulation of the brain moving around?

Holden Karnofsky: Yeah, exactly. You would have a simulated brain in a simulated environment. Absolutely, that’s another way to think of it.

Rob Wiblin: This is a fairly out-there technology, the idea that we would be able to reproduce a full human being, or at least the most important parts of a human being, running on a server. Why think that’s likely to be possible?

Holden Karnofsky: I mean, I think it’s similar to what I said before. We have this existence proof. We have these brains. There’s lots of them, and all we’re trying to do is build a computer program that can process information just how a brain would.

A really expensive and dumb way of doing it would be to just simulate the brain in all its detail, just simulate everything that’s going on in the brain. But there may just be smarter and easier ways to do it, where you capture the level of abstraction that matters. So maybe it doesn’t matter what every single molecule in the brain is doing. Maybe a lot of that stuff is random, and what really is going on that’s interesting, or important, or doing computational work in the brain is maybe the neurons firing and some other stuff, and you could simulate that.

But basically, there’s this process going on. It’s going on in a pretty small physical space. We have tonnes of examples of it. We can literally study animal brains. We do. I mean, neuroscientists just pick them apart and study them and try to see what’s going on inside them. And so, I’m not saying we’re close to being able to do this, but when I try to think about why would it be impossible, why would it be impossible to build an artefact, to build a digital artefact or a computer that’s processing information just how a brain would, and I guess I just come up empty.

But I can’t prove that this is possible. But yeah, the basic argument is just, it’s here, it’s all around us. Why wouldn’t we be able to simulate it at some point in time?

Rob Wiblin: Are you envisaging these digital people as being conscious like you and me, or is it more like an automaton situation?

Holden Karnofsky: One of the things that’s come up is when I describe this idea of a world of digital people, a lot of people have the intuition that even if digital people were able to act just like real people, they wouldn’t count morally the same way. They wouldn’t have feelings. They wouldn’t have experiences. They wouldn’t be conscious. We shouldn’t care about them.

And that’s an intuition that I disagree with. It’s not a huge focus of the series, but I do write about it. Basically if you dig all the way into philosophy of mind and think about what consciousness is, this is something we’re all very confused about. No one has the answer to that. But I think in general, there isn’t a great reason to think that whatever consciousness is, it crucially relies on being made out of neurons instead of being made out of microchips or whatever.

And one way of thinking about this is, I think I’m conscious. Why do I think that? Is the fact that I think I’m conscious, is that connected to the actual truth of me being conscious? Because the thing that makes me think I’m conscious has nothing to do with whether my brain is made out of neurons. If you made a digital copy of me and you said, “Hey, Holden, are you conscious?” That thing would say, “Yes, of course I am,” for the same exact reason I’m doing it: it would be processing all the same information, it’d be considering all the same evidence, and it would say yes.

There’s this intuition that whatever consciousness is, if we believe it’s what’s causing us to think we’re conscious, then it seems like it’s something about the software our brain is running, or the algorithm it’s doing, or the information it’s processing. It’s not something about the material the brain is made of. Because if you change that material, you wouldn’t get different answers. You wouldn’t get different beliefs.

That’s the intuition. I’m not going to go into it a tonne more than that. There’s a thought experiment that’s interesting that I got from David Chalmers, where you imagine that if you took your brain and you just replaced one neuron with a digital signal transmitter that just fired in all the same exact ways, you wouldn’t notice anything changing. You couldn’t notice anything changing, because your brain would be doing all the same things, and you’d be reaching all the same conclusions. You’d be having all the same thoughts. Now, if you replaced another one, you wouldn’t notice anything, and if you replaced them all, you wouldn’t notice anything.

Anyway, so I think there’s some arguments out there. But I think it is the better bet that if we had digital people that were acting just like us, and the digital brains were doing the same thing as our brains, that we should care about them. And we should think of them as people. And we probably would. Even if they weren’t conscious —

Rob Wiblin: Because they would act like it.

Holden Karnofsky: Yeah, well, we’d be friends with them.

Rob Wiblin: They would complain the same way.

Holden Karnofsky: We’d talk to them and we would relate to them. There are people I’ve never met, and they would just be like any other people I’ve never met, but I could have video calls with them and phone calls with them. And so, we probably will and should care about what happens to them. And even if we don’t, it only changes some of the conclusions. But I basically think that digital people would be people too.

Rob Wiblin: I mean, the argument that jumps to mind for me is if you’re saying, “Well, to be people, to be conscious, to have value, it has to be run on meat. It has to be run on these cells with these electrical charges going back and forth.” It’d be like, “Did evolution just happen to stumble on the one material that could do this? Evolution presumably didn’t choose to use this particular design because you’d be conscious. So why would there be this coincidence that we have the one material out of all of the different materials that can do these calculations that produces moral value?”

Holden Karnofsky: That’s an interesting way of thinking of it. If I were to play devil’s advocate, I would be like, “Well, maybe every material has its own kind of consciousness, and we only care about the kind that’s like our kind,” or something. But then that would be an interesting question why we only care about our kind.

Jeff Sebo on grappling with our biases and ignorance when thinking about sentience [00:38:59]

From episode #173 – Jeff Sebo on digital minds, and how to avoid sleepwalking into a major moral catastrophe

Luisa Rodriguez: Let’s actually talk about another paper of yours, “The rebugnant conclusion.” I love that title, by the way.

Jeff Sebo: Thank you!

Luisa Rodriguez: In the paper you basically ask: Suppose that we determine that large animals like humans have more welfare on average, but that small animals like insects have more welfare in total. What follows for ethics and politics?

And the paper focuses on small animals like nematodes, but the same question is relevant to AI systems that might end up being super numerous — perhaps because they’re used all over the economy — but that might also have some non-negligible chance of experiencing pain and pleasure.

So let’s start with the case that you actually focus on in the paper, which is small animals. How should we think about this case?

Jeff Sebo: I think we can start really at the end of the last exchange about ways of striking a balance if we worry about the harms of false positives and false negatives. One thing that you can note is that, even if I include insects and AI systems and other types of beings in my moral circle, even if I give them moral consideration, I might still be able to prioritise beings like me for different reasons.

One of them is that I might have a higher capacity for welfare than an insect or an AI system. I have a more complex brain and a longer lifespan than an insect, so I can experience more happiness and suffering at any given time, as well as over time.

And humans in general, I might think, are more likely to be sentient and morally significant — given the evidence available to me — than insects, AI systems, other beings like that. So I might think to myself that if a house is burning down and I can save either a human or an ant, but not both, then I can justifiably save the human — both because the human is more likely to matter, and because the human is likely to matter more. And those are perfectly valid ways of breaking a tie.

That might give us some peace of mind when we countenance the possibility of including these very different, very numerous beings in the moral circle. But then you have to consider how large these populations actually are — and this is where we get to the problem that this paper addresses, which is a problem in population ethics.

Luisa Rodriguez: Right. And population ethics is the philosophical study of the ethical problems that come up when our actions affect how many people are born in the future, and who exactly is born.

But yeah, my understanding is that we don’t actually know how many of these small animals there are — ants and nematodes and maybe even microbes — but that it’s at least plausible that there are so many of them that even if they have very less significant kinds of suffering and pleasure relative to humans, and even if we only put some small chance on them even having those at all, their interests still just swamp humans’. And this argument just does sound plausible to me, and it also fills me with dread and fear. What is your experience of it?

Jeff Sebo: Well, I certainly have the same experience as I think most humans do. And the reason I gave that paper the title “The rebugnant conclusion” is that this is based on a famous book by the philosopher Derek Parfit called Reasons and Persons, part four of which addresses population ethics. In that part of that book, Derek Parfit discusses what he calls the repugnant conclusion. I can say briefly what that is and why that has, for the past several decades, filled many people with dread.

So the repugnant conclusion results from the following observations. If you could bring about one future where the world contained 100 people and everyone experienced 100,000 units of happiness, or you could bring about another world with twice the number of people, 200 people, but everyone experiences one fewer unit of happiness — 99,999 — which world is better? Well, many of us have the intuition that the second world is better; I should bring about that second population. Everybody might experience one unit of happiness less per person, but since there are twice as many people, there is nearly twice as much happiness overall, and everyone is still really happy. And so, all things considered, I should bring about that population.

But then you can imagine another population, once again twice as big, and once again with a bit less happiness per person. Then another one twice as big, a bit less happiness per person. And so on and so on and so on — until you reach a point where you are imagining a world or a solar system or a galaxy that contains a vast number of individuals, each of whom has a life only barely worth living at all. And your reasoning would commit you to the idea that that is the best possible world, the one that you should most want to bring about.

Parfit thought the idea that we would favour that world with a much larger population, where everyone has a life barely worth living at all, over a world with a still significant population, where everyone has lives very much worth living, he found that repugnant. And he spent much of the rest of his career trying and failing to find a better way to see the value of populations that could avoid that result.

Luisa Rodriguez: I guess in the case of insects, there’s also this weird thing where, unlike humans eating potatoes and not particularly enjoying their monotonous lives, we might think that being a spider and making a web sounds pretty boring, but we actually just really do not know. In many ways, they’re so different from us that we should have much lower probability that they’re not enjoying or enjoying that than we do of humans in this repugnant conclusion scenario. How do you factor that in?

Jeff Sebo: I do share the intuition that a very large insect population is not better off in the aggregate than a much smaller human population or elephant population. But for some of the reasons that you just mentioned and other reasons, I am a little bit sceptical of that intuition.

We have a lot of bias here and we also have a lot of ignorance here. We have speciesism; we naturally prefer beings and relate to beings when they look like us — when they have large eyes and large heads, and furry skin instead of scaly skin, and four limbs instead of six or eight limbs, and are roughly the same size as us instead of much smaller, and reproduce by having one or two or three or four children instead of thousands or more. So already we have a lot of bias in those ways.

We also have scope insensitivity — we tend not to be sensitive to the difference that very large numbers can make — and we have a lot of self-interest. We recognise that if we were to accept the moral significance of small animals like insects, and if we were to accept that larger populations can be better off than smaller populations overall, then we might face a future where these nonhuman populations carry a lot of weight, and we carry less weight in comparison.

And I think some of us find that idea so unthinkable that we search for ways to avoid thinking it, and we search for theoretical frameworks that would not have that implication. And it might be that we should take those theoretical frameworks seriously and consider avoiding that implication, but I least want to be sceptical of a kind of knee-jerk impulse in that direction.

Luisa Rodriguez: Yeah, I am finding that very persuasive. Even as you’re saying it, I’m trying to think my way out of describing what I’m experiencing as just a bunch of biases — and that in itself is the biases in action. It’s me being like, no, I really, really, really want to confirm that people like me, and me, get to have… I don’t know. It’s not that we don’t have priority — we obviously have some reason to consider ourselves a priority — but I want it to be like, end of discussion. I want decisive reasons to give us the top spot. And that instinct is so strong that that in itself is making me a bit queasy about my own motivations.

Jeff Sebo: Yeah, I agree with all of that. I do think that we have some reason to prioritise ourselves, and that includes our welfare capacities and our knowledge about ourselves. It also includes more relational and pragmatic considerations. So we will, at least in the near term, I think have a fairly decisive reason to prioritise ourselves to some extent in some contexts.

But yeah, I agree. I think that there is not a knock-down decisive reason why humanity should always necessarily take priority over all other nonhuman populations — and that includes very large populations of very small nonhumans, like insects, or very small populations of very large nonhumans. We could imagine some kind of super being that has a much more complex brain and much longer lifespan than us. So we could find our moral significance and moral priority being questioned from both directions.

And I think that it will be important to ask these questions with a lot of thought and care and to take our time in asking them. But I do start from the place of finding it implausible that it would miraculously be the case that this kind of population happens to be the best one: that a moderately large population of moderately large beings like humans happens to be the magic recipe, and we matter more than all populations in either direction. That strikes me as implausible.

Bob Fischer on how to think about the moral weight of a chicken [00:49:37]

From episode #182 – Bob Fischer on comparing the welfare of humans, chickens, pigs, octopuses, bees, and more

Luisa Rodriguez: Just to make sure I understand, the thing is saying that the capacity of welfare or suffering of a chicken in a given instant is about a third of the capacity for the kind of pain and pleasure a human could experience in a given instant. Is that it?

Bob Fischer: That’s the way to think about it. And that might sound very counterintuitive, and I understand that. I think there are a couple of things we can say to help get us in the right frame of mind for thinking about these results.

One is to think about it first like a biologist. If you think that humans’ pain is orders of magnitude worse than the pain of a chicken, you’ve got to point to some feature of human brains that’s going to explain why that would be the case. And I think for a lot of folks, they have a kind of simple picture — where they say more neurons equals more compute equals orders of magnitude difference in performance, or something like that.

And biologists are not going to think that way. They’re going to say, look, neurons produce certain functions, and the number of neurons isn’t necessarily that important to the function: you might achieve the exact same function using many more or many fewer neurons. So that’s just not the really interesting, relevant thing. So that’s the first step: just to try to think more like a biologist who’s focused on functional capacities.

The second thing to say is just that you’ve got to remember what hedonism says. What’s going on here is we’re assuming that welfare is about just this one narrow thing: the intensities of pleasures and pains. You might not think that’s true; you might think welfare is about whether I know important facts about the world or whatever else, right? But that’s not what I’m assessing; I’m just looking at this question of how intense is the pain.

And you might also point out, quite rightly, “But look, my cognitive life is richer. I have a more diverse range of negatively valenced states.” And I’m going to say that I don’t care about the range; I care about the intensity, right? That’s what hedonism says: that what matters is how intense the pains are.

So yeah, “I’m very disappointed because…” — choose unhappy event of your preference — “…my favourite team lost,” whatever the case may be. And from the perspective of hedonism, what matters about that is just how sad did it make me? Not the content of the experience, but just the amount of negatively valenced state that I’m experiencing, or rather the intensity of the negatively valenced state that I’m experiencing. So I think people often implicitly confuse variety in the range of valenced states with intensity.

Luisa Rodriguez: Yeah, that’s definitely something I do. For sure there is a part of me that thinks that the thing that matters a lot here is that I can fall in love in a particularly meaningful and big way; I can have friendships lasting 50 years that involve really deep and meaningful conversations. And that even if a chicken has meaningful relationships with other chickens, they’re not as complex and varied as the relationships I have with people in my life.

On the other hand, a big part of me puts a bunch of weight, when I really think about it, on just like, no, what matters is the intensity. If a chicken feels more sad about her wing being broken than I feel about losing a friend, then so be it. We should make sure that their wings aren’t broken before we should make sure that whatever threat that could mean I lose my friend [is prevented].

And I guess lots of listeners will have their own kind of internal turmoil about this, about what welfare even is. But for now, I guess if we’re just taking this assumption, which is that what matters is the intensity, your finding is that something like averting the suffering of three chickens for an hour is similarly important to averting the suffering of one person for an hour. And that feels uncomfortable to me. Can you talk me through that discomfort?

Bob Fischer: Sure. So the first thing to say is: you’re not alone. I don’t feel totally comfortable either. And we have to ask ourselves what our most serious moral commitments are when we’re approaching this question. So you’re not going to avoid really uncomfortable, challenging questions when we try to think about moral weights — just not going to go away.

But here are a few things to say. One is: is there any number that you wouldn’t be uncomfortable with? Because notice that if you’re committed to this idea of doing conversions, eventually it’s going to just work out that you’ve got to say there is some number of hours of chicken suffering that is more important than helping a human.

And I think actually for a lot of people, they don’t really think that there is any conversion at all, right? If I had said it was 300, would you really have felt that much better? You might have felt a little bit better; I’m not saying you wouldn’t felt it at all. Sure, it’s a difference, but you might still say, when you really think about it: “Three hundred hours? Would I put somebody through that for… chickens?” And then you might just have the same level of discomfort, or something close to it.

So I think to some degree we have to remember that the tradeoffs that we’re talking about come from background theoretical commitments that have nothing to do with our specific welfare range estimates: it comes from the fact that we’re trying to do the most good. We think that means making comparisons across species, and we’re committed to this kind of maximising ethic that says, yeah, there is some tradeoff rate, and you’ve got to find it.

So that’s the first thing to say about the discomfort. Before I say anything else, what do you think about that?

Luisa Rodriguez: Yes, some of that definitely worked for me. I think the thing that lands most is if I think about chickens on a railroad track, and there’s a trolley coming, and there’s a human on the other side, it is pretty impossible for me to imagine getting to the point where I’m ever super comfortable being like, “I’m going to let it hit the human, who I could have conversations with, who has a family I might know, who I could give a hug to, and who has a job…” These are all the things that kind of run through my head as I’m deciding whether to pull a lever to decide who gets hit by this trolley. And so, fair enough that that is something I have to grapple with, regardless of exactly what these numbers are.

Bob Fischer: And just to tag on to that, think about it when you put someone you really care about on the track. So I think about this with my children, and say, look, it might well be the case that there’s almost no number of other humans I would choose to spare, given the choice between killing my own children and them. But that’s not because I think they actually matter less in some objective sense. Like when I’m trying to do the impartial good, I would never say, “Oh yes, my children are utility monsters: they have infinite worth and everybody else has just some tiny portion of that.”

So when we recognise that our moral judgements are so detached from our judgements of value, that also can help us think about why these welfare ranges might not be quite so crazy.

Luisa Rodriguez: Yeah. Was there anything else that helps you with the discomfort?

Bob Fischer: I think the thing that helps me to some degree is to say, look, we’re doing our best here under moral uncertainty. I think you should update in the direction of animals based on this kind of work if you’ve never taken animals particularly seriously before.

But ethics is hard. There are lots of big questions to ask. I don’t know if hedonism is true. I mean, there are good arguments for it; there are good arguments for all the assumptions that go into the project. But yeah, I’m uncertain at every step, and some kind of higher-level caution about the entire venture is appropriate.

And if you look at the way people actually allocate their dollars, they often do spread their bets in precisely this way. Even if they’re really in on animals, they’re still giving some money to AMF. And that makes sense, because we want to make sure that we end up doing some good in the world, and that’s a way of doing that.

Luisa Rodriguez: I guess I’m curious if there’s anything you learned, like a narrative or story that you have that makes this feel more plausible to you? Anything particular about chickens or just about philosophy? You’ve already said some things, but what story do you have in your head that makes you feel comfortable being like, “Yes, I actually want to use these moral weights when deciding how to allocate resources”?

Bob Fischer: There are two things that I want to say about that. One is I really worry about my own deep biases, and part of the reason that I’m willing to be part of the EA project is because I think that, at its best, it’s an attempt to say, “Yeah, my gut’s wrong. I shouldn’t trust it. I should take the math more seriously. I should try to put numbers on things and calculate. And when I’m uncomfortable with the results, I’m typically the problem, and not the process that I used.” So that’s one thing. It’s a check on my own tendency to discount animals, even as someone who spends most of their life working on animals. So I think that’s one piece.

The other thing is just to spend time thinking about the kinds of things animals can do and what their lives are like. Just how hard a chicken will work to get to a nest box before she lays an egg, the amount of labour she’s willing to go through to do that, to think about how important that is to her. And to realise that we can quantify that, and see how much they care, or to see that they get stressed out when fellow chickens are threatened and that they seem to have some sympathy for conspecifics.

Those kinds of things make me say there is something in there that is recognisable to me as another individual, with desires and preferences and a vantage point on the world, who wants things to go a certain way and is frustrated and upset when they don’t. And recognising the individuality, the perspective of nonhuman animals, for me, really challenges my tendency to not take them as seriously as I think I ought to, all things considered.

Cameron Meyer Shorb on the range of suffering in wild animals [01:01:41]

From episode #210 – Cameron Meyer Shorb on dismantling the myth that we can’t do anything to help wild animals

Luisa Rodriguez: Fundamentally, why do you worry about suffering among wild animals? What kinds of things make you think that they might be suffering a lot in particular?

Cameron Meyer Shorb: I’m wildly uncertain about what the nature of wild animals’ lives are like. But I got into this field because I changed my mind about the possibilities here. I used to just assume that animals living in the wild were perfectly in balance, and living totally fulfilled lives, and weren’t bothered by any of the stresses of modernity like I am — and that the best thing humans could possibly do for them is just leave them alone there.

But the more I learned about it and thought about it, the more I realised that there’s actually lots of reasons to think that wild animals might not be living great lives, at least many of them. For example, they often have to struggle to get enough food. They often need to struggle to protect themselves from extreme weather. There are some kinds of things where they have no protection at all: if a flood or a wildfire comes, that’s just the end of it for them. There’s also all sorts of diseases or parasites. They have no healthcare. They also have no state to protect them from violence, either from other species or even members of their own species.

So the kinds of conditions we’re talking about here, when humans live in those conditions, we would call that poverty. And we wouldn’t tolerate that. We would say that those are problems we need to solve; those are people who deserve better lives. And if we have medicine, we should help give them access to medicine. If there’s ways to give them more stable access to food, that’s something that would improve their lives.

That’s the kind of approach that I now think we should consider taking when we think about wild animals: taking seriously the idea that they might be struggling even in their natural habitats, and they might suffer even from naturally occurring harms. And we should try to figure out to what extent that’s true, and if it’s possible to do anything about that.

Luisa Rodriguez: Yeah, I want to come back to some of those, because I feel like even though I’m a little bit familiar with this problem, I still have a super limited imagination for the kinds of things that wild animals — and obviously there’s such a wide range across different species — might be going through, aside from the really obvious ones, like being eaten or something.

So putting a pin in that, what is the scale of the problem? How many individuals alive right now are wild animals?

Cameron Meyer Shorb: The scale is huge. It’s bigger than I can count. I’ve been humbled by learning about this, but I do think the scale is such an important part of understanding the problem.

Just in the broadest possible strokes, based on the rough numbers we know, it looks like something like 99% of all sentient minds alive on Earth today are wild animals. So if you are a human or a farmed animal, that is an incredibly rare exception to the rule, which is: things that can feel live in the wild. You’re more of a rounding error than anything.

Which is not to say that human and farmed animal experiences aren’t important; it’s just to say there is a lot more going on. And a truly impartial view of ethics would have us believe that ethics is mostly about wild animals… and also there are these interesting subfields that are related to some primates and farmed animals.

Luisa Rodriguez: OK, I’m interested in breaking down the numbers a bit more. I feel like it seems at least kind of important to know, are we mostly thinking about zebras, or are we mostly thinking about fish, ants…? What to think about feels like it could have helpful effects in helping me figure out, what are we talking about?

Cameron Meyer Shorb: That’s a great question to ask, because I think that the images that normally come to mind are not the most representative of wild animals. Most minds are wild, weird, and wet. They’re just not humans or human-like things.

To try to get a sense of scale, I’ll suggest a visualisation. Let’s imagine for the sake of this exercise that we’re going to put a dot down of equal size for any individual that’s alive. So one dot for a human, one dot for a squirrel — and you can debate later how you want to make tradeoffs across species — but just for starters, to get a sense of the raw numbers.

Now, let’s make these dots small enough so that we can fit all 8.2 billion humans onto the face of a quarter or a euro — so something a little smaller than one square inch.

If we’re keeping that scale, then the 88 billion wild mammals would take up an area about the size of a credit card or a post-it note.

And then when we move on to birds — and I should say these estimates are all very rough, and the bigger the populations, the wider the error bars are — but for birds, let’s say there are about 200 billion living in the wild. That would be something about the size of a standard envelope.

And then for reptiles and amphibians, each of those numbers somewhere around one trillion individuals, two trillion put together. So a trillion would be a standard sheet of paper. I think this is a good place to pause and just think about how far we’ve come: from a quarter to an envelope, which is way bigger than a quarter, to a couple sheets of paper — compared to a quarter that contains all of human experience and 8.2 billion lives. There’s that, times many, many more, if you’re trying to encompass humans and mammals and birds and reptiles and amphibians.

Then the numbers get even more mind-boggling when we move on to fish. There’s something like 10 trillion fish in the world. So 10 trillion fish would be something like the size of a medium-sized desk — the Linnmon from Ikea, if you will — or a large bath mat, or a couple of pillowcases maybe. That’s what the whole fish population would look like, relative to the human population fitting on a quarter.

And the numbers get really… I don’t know what “to boggle” means literally, but I think it is something like what is happening to my mind. I think it is mind-boggling to try to imagine the number of plausibly sentient invertebrates.

The only at all close-to-useful number I found here is an estimate of the number of terrestrial arthropods — that would be animals with hard exoskeletons, like insects and arachnids and crustaceans. So for those that live on land, estimates are that their population is somewhere around 100,000 trillion. If 8.2 billion humans fit on the face of a quarter, 100,000 trillion would need to be something the size of a city block or a FIFA regulation-size soccer field.

Luisa Rodriguez: That’s insane!

Cameron Meyer Shorb: Imagine standing at any point in a soccer field and looking at a quarter and then looking around at the rest of the field. It really changes your perspective on what life on Earth is like, who’s really living here. And it’s hard to know whether many arthropods are sentient. I think there’s decent questions and considerations on either side. But one of the things that I think is important to consider is the expected value. So even if there’s just a 10% chance that they are, 10% of a soccer field is still way bigger than a quarter.

Luisa Rodriguez: Yeah. This makes me really happy that some of our most recent episodes… One is with Meghan Barrett, one of my favourite episodes of all time, on invertebrate sentience. And really, it took me well above 10% probability or credence that invertebrates are sentient. Another one is on fish with Sébastien Moro, just infinite numbers of bewildering facts about fish.

For me, invertebrates and fish both make up tremendous numbers of individuals, as you’ve just said, and just are clearly at least very plausible sentience candidates. For the case of fish, it seems hard to even debate for me. So given that these are the animals making up most of the wild nature we’re talking about, for anyone who’s interested, I can recommend those episodes.

Sébastien Moro on whether fish are conscious or sentient [01:11:17]

From episode #205 – Sébastien Moro on the most insane things fish can do

Luisa Rodriguez: This is fascinating and mind-blowing, purely from the perspective of “fish are incredibly cool.” But do these feel like they tell you anything about whether fish are experiencing these things in some conscious way or affective way?

Sébastien Moro: As I said earlier, we have to split consciousness and sentience, which are not the same thing. It’s very hard actually talking about real consciousness, like high-order consciousness, like humans: we don’t know how to assess it correctly, even in humans. We don’t have proper assessing tools.

So today we’re trying to build new ways to assess consciousness and sentience and split them properly. I understood that you’ve interviewed Jonathan Birch about that. He’s a pioneer in it. He’s a very important person on it.

There is a very good book, especially on fish, a study which is named, “What is it like to be a bass? Red herrings, fish pain, and the study of animal sentience.” It’s a publication from 2022. It’s really interesting because it’s coming back on all of this, and the famous study that was talking about modification of the mirror test we were talking about. Many of the studies that were done that we’ve talked about, they aren’t made to assess sentience.