5 ways to be misled by salary rankings

Suppose that you plan, like many members of Giving What We Can or the Giving Pledge, to give a significant portion of your income to highly effective causes, and as one factor in your career decision you want want to assess how much you will be able to donate in various fields.

National wage and employment surveys, such as the UK Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings or the US Occupational Employment Statistics database provide good places to start. However, typical salary is an imperfect measure of career earnings. This post discusses five ways in which the national surveys can mislead at first glance, particularly for the most financially rewarding areas, in hopes of providing some protection to the casual explorer and explaining how in-depth analysis can help.

High-wage fields in the United Kingdom

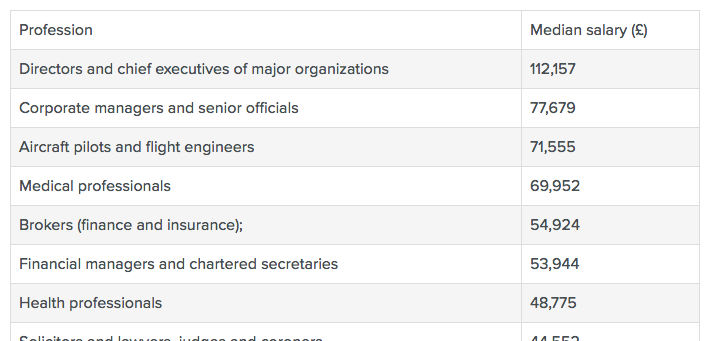

For the moment, most of the membership of 80,000 hours is based in the UK, so I will use the 2011 ASHE statistics to set the stage. One can download the data here, view a table ranking UK occupations by median income in ASHE here, or just consider these high-income occupations (the top 4, followed by a selection of others near the top):

Profession | Median salary (£) |

Directors and chief executives of major organizations | 112,157 |

Corporate managers and senior officials | 77,679 |

Aircraft pilots and flight engineers | 71,555 |

Medical professionals | 69,952 |

Brokers (finance and insurance); | 54,924 |

Financial managers and chartered secretaries | 53,944 |

Health professionals | 48,775 |

Solicitors and lawyers, judges and coroners | 44,552 |

Electronics engineer | 43,772 |

Mechanical engineer | 39,142 |

Corporate managers | 38,091 |

Software professionals | 36,634 |

Architect | 36,375 |

Pharmacists/pharmacologists | 36,211 |

Management accountants | 35,851 |

The presence of management and leadership roles is unsurprising: these are senior positions by definition. Other occupations are disproportionately ones that require an uncommon, specialized skill or advanced education. Unfortunately, several of these fields exemplify particular limitations of the data.

Non-wage compensation

The ASHE survey considers only wages and certain cash bonuses. For example, it leaves out self-employment, partnership income, business ownership, restricted stock, and stock options. This is particularly pernicious, since so many of the most lucrative careers make heavy use of these compensation methods.

Professional services firms in law, accounting, and management consulting are typically organized as partnerships, with partners receiving the profits of the firm (in a fashion reflecting their labor contributions similar to ordinary wages, save for fluctuating more with firm outcomes). In this survey of law profits for 200 of the largest British law firms, overall profit margins tend to be in the 20-40% range, making law significantly more attractive than the ASHE data would suggest.

In finance, the immense incomes of hedge fund and private equity managers have primarily taken the form of carried interest, treated as return on investment in their funds rather than as a wage. At investment banks in the City of London and Wall Street restricted stock and stock options play a much larger role in compensation for non-executive employees than in most other industries (although of course this does play a substantial role for senior executives and employees in startup-rich industries).

Also worth mentioning is the role of oversize pensions in some areas, particularly in government, where increasing pensions is less controversial than raising salaries.

Career length: education, experience and exit options

ASHE statistics reflect the incomes of those who are currently working in an occupation, but not income associated with any pre-requisite steps.

For some of the high-salary categories taking pre-requisites into account makes a large difference: it is rare to become a “director or chief executive of a major organization” without paying one’s dues for years in more junior positions, save perhaps through successful early entrepreneurship. A British physician must first complete a long degree, requiring 5 or 6 years as a first course, before taking training positions with the NHS. The additional years of schooling mean substantial foregone earnings, and the loss of any chance for investment or social returns on the earnings. In the U.S., where a 4 year medical degree must be preceded by another (usually 4-year) degree, this is an even larger penalty.

On the other side, some fields normally offer short careers. In the extreme, models or athletes may be lucky to have a 3 year career. More importantly, while a physician will usually remain a physician throughout her career, lucrative jobs in investment banking and management consulting often come with “up or out” career paths. Either one is promoted “up,” with incomes growing exponentially, as one can see in these links for banks and consultancies, or one is fired “out” and must seek work at a lesser firm or leave the industry. Since most employees will not be around for very long, one must take into account one’s “exit options” in deciding whether to enter.

Matched wages and expenses

For a business, the key measure is not revenue earned, but the profit after costs are deducted. Similarly, some jobs carry additional costs that substantially reduce their expected financial rewards. Some of these costs are fairly direct, e.g. professional school tuition, business attire, and costs of expensive socializing with work colleagues. Tuition costs can be severe, but are often highly subsidized by government.

Lucrative positions also often require living in relatively expensive cities, with higher housing prices and cost-of-living. The global financial industry is disproportionately concentrated in the City of London and downtown Manhattan in New York City, areas with extremely high real estate prices. Long hours and congestion necessitate renting or purchasing property near work as the opportunity costs of commuting are driven to very high levels. Technology workers and entrepreneurs in Silicon Valley face similarly high real estate costs. These locations also tend to have high state and local tax rates, as governments exploit immobile concentrations of wealth: in the U.S. California (Silicon Valley and Hollywood) and New York have the highest state taxes, with New York City exacting additional income tax to capture Wall Street wealth.

Heterogenous categories

Median figures for broad occupational classifications can conceal enormous sub-category variation. In previous posts I discussed how uncommon but extreme impacts can be important in assessing the expected impact of entrepreneurship and politics, but similar considerations also apply in other fields, particularly finance.

Some statistical categories include quite different career tracks, e.g. a “financial workers” category that included both stockbrokers and investment bankers. These jobs require very different skills, and one knows which one is entering in advance. Different medical medicine different subspecialties can bring different earnings, and odds of getting a chosen specialty can vary with medical school and performance (which can be predicted with GPA and MCAT score in the US, similar stuff for UK).

Industry risk

Over time industries rise and fall. Since 1970, the financial industry (construed broadly) has greatly increased its share of the US and UK economies, but this process has reversed itself before: it took 60 years from the start of the Great Depression for finance as a share of GDP to recover. Investment banking compensation fluctuates wildly with the movement of the economy and the stock market: some studies have claimed that boom or bust on Wall Street affects the expected earnings of elite business school graduates by millions of dollars, reducing both the number and compensation of investment banking jobs available.

While predictable short term fluctuations can be dealt with tactically (e.g. delaying entrance to business school in a crash year), and medium-term fluctuations can be averaged over (using historical data) when evaluating the expected value of undertaking career, large shifts in the economy can devalue (or revalue) a sector and are hard to precisely predict. For such sectoral shifts, one can simply note that one is paying attention to a field because the combination of lasting and temporary factors has made it lucrative, and regress towards the mean across sectors when looking into the distant future.