Transcript

Rob’s intro [00:00:00]

Hi listeners, this is the 80,000 Hours Podcast, where we have unusually in-depth conversations about the world’s most pressing problems, what you can do to solve them, and how to get votes from both the 50-64 demographic, and the negative 150 to negative 164 demographic. I’m Rob Wiblin, Head of Research at 80,000 Hours.

You’ll be relieved to know that our 118 episode drought of interviews without someone who’s run for president of the United States has finally ended.

Andrew Yang is someone who’s generated a lot of interest among listeners of this show — focusing on topics a lot of politicians won’t go near, like UBI, or what might happen when AI replaces whole industries.

But those topics are still… pretty vanilla compared to what we often talk about on here, and so we set out to cover things Andrew hasn’t commented on before, such as:

- Whether we should be spending more to reduce existential risks

- Whether it’s reasonable to worry about AI tail-risk scenarios

- Why he advocates ranked-choice voting over approval voting

- Whether it makes sense to treat future generations as a disenfranchised group

- His views on alternative meat

- The benefits of utopian outlooks, and where he hopes humanity will be in 500 years

- What he’d do with a billion dollars

- The worry that he’ll cause harm by running a third party candidate for his new Forward Party

- And plenty more.

It was really fun to see the substantial areas where Andrew’s views aligned with the effective altruism and longtermism communities, and for someone involved in politics I found him to be refreshingly open and candid. If you know someone who’s into Andrew but hasn’t heard this show, this might be a good episode to share.

Alright, without further ado, I bring you Andrew Yang.

The interview begins [00:01:38]

Rob Wiblin: Today I’m speaking with Andrew Yang. Andrew is an American politician who is currently working to establish a new US political party, which will be called the Forward Party. He is most well-known for running for president in the 2020 Democratic primaries, as well as running to become New York mayor earlier this year. Last month, while announcing his intention to launch the Forward Party, he also published his new book, Forward: Notes on the Future of Our Democracy, which features memoirs from his presidential run, as well as his proposed solutions to the problems he identifies in US politics today. Thanks so much for coming on the podcast, Andrew.

Andrew Yang: Rob, thank you for having me. It’s great to be here.

Rob Wiblin: Obviously, you get to talk about the challenges the US faces right now, and the policies you’d like to see implemented to tackle them on a regular basis. This show is maybe most unusual for making time to think about what we want in the seriously long term — like hundreds or thousands of years, or maybe even longer in the future — and then also taking seriously how listeners might be able to help make sure that humanity stays on track to get there.

Rob Wiblin: Today, I thought it would be really fun to go much further than I imagine you typically get the chance to, and take time to zoom out and reflect on the really big-picture situation in which humanity finds itself right now, before we return to some more nuts-and-bolts issues towards the end of the conversation. Sound good?

Andrew Yang: Sure thing, Rob. Congratulations on the work you all do. I’m a huge fan of people who are trying to figure out how to improve the human condition and thinking long-term, because right now we don’t have enough of either of those things.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah, I really appreciate that. There’s so much talk about problems, and I think that makes a lot of sense, because you’ve got to think about what the big problems are in the world. But it’s also important to stay motivated by realizing that there’s so many practical things we can do to fix those issues that we’re worried about.

Andrew’s hopes for the year 2500 [00:03:10]

Rob Wiblin: But before we get to that, first off: if you could somehow return to visit Earth in 500 years, once we’d hopefully advanced technologically and matured much more as a species, what would be close to the ideal future for humanity that you’d like to come back and see in the year 2500?

Andrew Yang: Hopefully, at that point, we are living in harmony with our environment — we’ve managed to reverse some of the calamitous effects of carbon emissions and climate change. And that people are living in a variety of different ways, some of which I imagine would be retro-seeming. Ideally, you’d have people living in communal living environments, and rural areas, and maybe doing some forms of the work that we have been doing for a long time — but not really because you need to, but because it’s actually something that people enjoy and get value out of.

Andrew Yang: And you can engage in creative pursuits, again, without a concern whether someone buys your poem, or something along those lines. There are all of these intrinsic goals that people are able to pursue, and do so in a way that isn’t grow, grow, grow. It isn’t about accruing tons of resources. That would be my ideal hope for the species.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. I guess at this time, you’re imagining most things are in the fully automated world, so people can spend most of their time hanging out with friends and family, and building relationships, and focusing on their community, and they don’t have to go and do a job just to survive.

Andrew Yang: Yeah. We would’ve been able to meet people’s material needs. And so then the question is: what fills that social and spiritual set of needs that people have? Which in some ways is a more difficult, thorny problem. Though the political environment necessary to properly distribute the fruits of technological advancement is another problem that everyone knows I’m very concerned about.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. A lot of people are worried that in a post-necessary-work world, that folks won’t enjoy their lives anymore, because it’s work that gives life meaning. Personally, I’m not too concerned about that. I feel like I could not do a job and I could hang out with my friends and have a good time, and I don’t know that I’ll get sick of that. How do you feel about that issue?

Andrew Yang: I’d say I’m somewhere in between, Rob, because I personally also feel like I’d have no trouble chilling out. But I’ve met hundreds, thousands of truck drivers and people in different environments where they are very much defined by their work, often in terms of economic value. Where if you’re a trucker, I kid you not, they’re measuring how many dollars they make per mile. And so, every time that mile counter goes up, it’s a little bit more money coming to them. And so, if you unplug from that… I mean, you’ve seen the dystopian projections where you’d have fake jobs, where someone just plugs in.

Rob Wiblin: Very Black Mirror.

Andrew Yang: Yeah. There is a very significant number of human beings I’ve met who would not be able to just adapt easily to relative free time.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. One thing that makes me hopeful about that is we see, globally, quite a lot of variation in how much people define themselves through their work. I think the US leans a bit more towards people being very work- and career-focused and getting a lot of their identity out of that. And there’s other countries, like the Netherlands famously has leaned more into this idea that it’s okay to work part-time, and maybe the most important thing is your friends and family. And work is just this thing you do to pay the bills, and that’s actually totally fine and normal, and isn’t a threat to people’s identity. So maybe over time we can evolve a bit more toward that mentality, where people develop other identities that help to substitute for what was previously something that came out of work.

Andrew Yang: Well, I enjoy the 500-year time frame, because then all things become possible. The transition would take generations in my view. And America, I agree with you, tends to be towards one extreme.

Tech over the next century [00:07:03]

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. What’s a technology that you’re really excited to see progress over the next century that you think people don’t talk about enough right now?

Andrew Yang: The next 100 years, I think there are two major issues coming down the pike, and they’re related to our politics. Number one is climate change — I think most people recognize that. And then number two is the advancement of AI and different technologies that will exacerbate income inequality, inevitably. And so if you ask what technologies I’m excited about in this time frame, it would be clean energy — something that allows us to be able to produce all of the energy we need that doesn’t have adverse environmental impacts — and some form of AI that we’re convinced is relatively benign, and can help drive value in a way that’s felt widely.

Andrew Yang: I’m going to describe something — this is a bit of inside baseball, but I think it’s interesting. I was a CNN commentator in 2020, and they asked me to develop ideas for a show. The show that we came up with was The Future Of, and we’d look at the future of various things. I thought that would be a good show, we’d do that. And then I ran for mayor of New York and then I came back to them, and we were shooting the shit over, “Okay, what are we going to do?” It turns out I ended up heading in a different direction, but they said, “Hey, The Future Of now is actually a double-edged sword. It has as much negative as positive, so we think we should head in a different direction.”

Andrew Yang: And I think in many ways, that’s what you all are trying to combat: you want people to be excited about the future and be optimistic about technology. But at least the opinion-makers, the media folks, are like, “Uh-oh. Things are starting to tend in a direction where we’re not sure people are really going to dig this.” So I just want to throw that in there as a real-life data point.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah, yeah. What do you think about upcoming technological solutions to the suffering of animals in factory farming? And the environmental damage that’s caused by meat production, which is pretty substantial? Things like cellular agriculture or plant-based protein sources? That’s one that looms large in my mind.

Andrew Yang: I love it. Certainly any of the meat substitutes, or if you can just develop meat in a way so that there are no animals involved, or no suffering. I love that stuff. Anytime I have an opportunity to consume it, if I have a choice, I’ll choose that. Because why not? And you have a sense that we’ll have the technology to be able to produce enough nutritional value and tastes for people, where they’re not going to miss anything.

Rob Wiblin: On the climate change and energy stuff, it feels like there’s a lot of areas where people are very pessimistic about everything. But climate change feels like one where there’s renewed energy about new technologies. Obviously, people are talking about solar, because it’s gotten so cheap, and it seems there’s a lot of advances coming through on batteries. But also geothermal seems to be having a renaissance this year. Fusion energy is back on the agenda. People are talking about passively safe, small nuclear reactors, which I think I didn’t hear at all about three or four years ago. It’s an area where I think people are getting a bit psyched.

Andrew Yang: I agree. That’s an area for tremendous optimism. Here in the States, I think we owe Elon Musk a great deal for advancing both people’s thinking about it and the implementation. I mean, there are electric car charging stations in places that they never were before. And so I’m optimistic. I spoke to Elon about this a little while ago, and he’s definitely, as people imagine, very, very bullish on solar, relative to the other energy forms. But talking to him also made me more bullish, so it’s a really positive feedback loop. I agree, there’s a lot of energy around it and it’s exciting.

Utopia for realists [00:10:41]

Rob Wiblin: So you had this experience with CNN. Personally, I would like to see a bit more hopefulness in public discourse, and maybe even a dash of utopianism. I think we could use it.

Andrew Yang: I agree with you. I think the guy over here — you’re probably friends with him, you remind me of him — is Rutger Bregman. He has managed to incept some people about… Well, his Utopia For Realists — I mean, the man has a very on-point title.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. You had a really good interview with him. Not only does it motivate people to work harder to try to create that world, but I think it can actually combat some of the division. Because we’re so focused on the problems of right now and the divisions and disagreements that we have. But if you’re thinking over a century, we could make the world so much better. We could get rid of colds. We could have clean energy. We could get rid of air pollution.

Andrew Yang: We could eradicate poverty.

Rob Wiblin: And I think people will actually maybe have more values in common, more shared goals than they appreciate.

Andrew Yang: Well, that’s what my presidential campaign did to a significant extent, Rob, where we were thinking big. But people imagined a world without poverty — or at least a country without poverty — and then they got excited about it. And it was fresh, it was different, because there wasn’t a political interest group that was invested in it and it wasn’t divisive.

Andrew Yang: Right now, the way American politics works is that it gets fueled by resources, so there’s a lot of us-versus-them. There’s a lot of polarization. So I’m with you: we have to get people excited. You’re right, and I’m still working toward that. I regret that democracy reform isn’t as utopian-seeming to many as universal basic income was, but I’m now convinced that they’re hand-in-hand — and that right now, the American political system won’t produce anything like UBI, unless it gets a significant upgrade.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. We’ll talk a bit about voting reform later, but I guess improving how we make decisions together can be revolutionary in the same way that some of these other technologies can be. It enables us to make better decisions across the board to invest in better science and technology and to solve poverty, because we’re actually able to reason together and choose solutions that are better than others.

Andrew Yang: I like it. I like it, Rob. Right, they are very much connected. I mean, they are obviously connected. It’s one reason I’m doing what I’m doing.

Most likely way humanity fails [00:12:43]

Rob Wiblin: Moving on for a second from the positive vision to ways that we might fail to get that world. What’s the most probable way that humanity fails to achieve the future that you would like, in your view?

Andrew Yang: Oh gosh, you can just look around us, man. Not much to be left to the imagination.

Rob Wiblin: Too much to choose from?

Andrew Yang: I like to think about things in terms of abundance versus scarcity. And a friend of mine, Xander Schultz, said to me we have a window of opportunity when we actually have the resources to provide for everyone, but that’s going to be threatened by climate change and authoritarianism. And he is correct.

Andrew Yang: Climate change is the big one. And in an environment of shrinking resources and flooding coastal areas and the rest of it, then people are going to be very much overtaken by scarcity. There’s going to be a sense of “resources are shrinking, not enough to go around.” I think it’s going to end up leading to some very, very nasty, negative sentiments. And then that ends up leading through to authoritarianism, where you see many democracies struggling with this a little bit. The US is struggling with it, in my opinion.

Andrew Yang: Those are the two biggest ways that we can screw it up. And that is the way we’re heading right now, in large part because we have institutional leadership that doesn’t really care whether these things get addressed, because their professional incentives don’t line up with it. No one loses their job if the Earth gets a little bit less habitable. That’s the most likely scenario. I think people can sense this — it’s one reason why positivity is a little bit harder to come by. Though again, I’m extraordinarily grateful to you all for galvanizing energy around positive visions. I like to think I do the same thing. And one of the reasons why I am excited is that hopefully enough of us will get fed up with the twin threats of climate change and authoritarianism, and try to turn us toward abundance.

What Andrew would do with a billion dollars [00:14:44]

Rob Wiblin: If someone gave you a billion dollars, Andrew, and said, “I’m also really worried about political decline or authoritarianism in the United States. And I would like you to make grants in order to try to reduce the risk of that happening.” Do you see any great opportunities out there for helping to heal things?

Andrew Yang: Oh my gosh, do I? Yes! I love this question so much. This is genuinely what I’m focusing on every day nowadays. I just want to go through the US political system. A lot of people are probably American here, but —

Rob Wiblin: It’s about half and half.

Andrew Yang: American democracy is genuinely under a lot of stress/threat, and it could disappear over the next several years in my opinion. You already have a position where millions of Americans don’t believe in vote totals. Trump’s probably going to run again. Depending upon the economic environment, he’d either be favored to win or he’ll say he won regardless — and then we can look forward to political violence and protests, and stress everywhere.

Andrew Yang: Political stress in the United States is at literal Civil War levels, according to Peter Turchin and other scholars. So if you gave me a billion dollars and said, “Hey, fix this,” then the path forward is to try and reduce the polarization in the United States. Because right now, 42% of both Democrats and Republicans view the other side as evil or their mortal enemies. And you have this binary dynamic.

Andrew Yang: By the way, this is historically unusual and also globally unusual. America is the only major democracy with two parties. It’s a terrible design. The founders would be shocked and horrified that we are limping along with two parties. It makes no sense. There’s nothing in the Constitution about this, for sure. It just arose and these two parties decided essentially to trade power. But these two parties were ideologically very, very similar until relatively recently — until the 60s and 70s. And so you only now see the fruits of a polarized duopoly, and the disaster that brings.

Andrew Yang: One of the disasters is that if one of the two major parties succumbs to bad leadership, everyone’s incentive is to fall in line or they lose their jobs. The counterexample to this was Senator Lisa Murkowski, who’s the only Republican senator who voted to impeach Trump earlier this year, and is also up for reelection. Her approval rating among Republicans in Alaska tanked: it’s now 6%. So it is indeed politically suicidal to go against Donald Trump.

Andrew Yang: But one reason why she did this is that they switched in Alaska from closed party primaries to open primaries and ranked-choice voting last year. So now instead of being beholden to the 10 to 20% most extreme partisan voters in Alaska, she can appeal to the general public, and if 50.1% of the Alaskan public says you’re okay, then she can still come back.

Andrew Yang: So if you gave me a billion dollars, we would do what they did in Alaska in, let’s call it 15 of the 24 states in the country that allow for ballot initiatives the same way that Alaska does. No act of Congress needed, all you need is a popular wave of people saying, “Look, I’m sick of my leaders being beholden to the 10 to 20% most extreme voters.” It disenfranchises the majority of the country. Right now, 10% of American voters elect essentially 83% of the representatives. You have an approval rating of 28% for Congress and a reelection rate of 92%. The incentives are all messed up. And if you had a billion dollars, you could run ballot initiative campaigns in over a dozen states and have a chance to win them all.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. Basically, you would fund campaigns to do ballot initiatives in order to change the primary system. There’s a bunch of changes that one could make, but in this case, to have a jungle primary where everybody runs, and then the top two candidates go through to the final —

Andrew Yang: The top five candidates, actually.

Rob Wiblin: Top five? And then do you do ranked-choice voting?

Andrew Yang: Yes. Ranked-choice voting is also a moderating impulse. What you’d see if you made this change is that all of a sudden, people would have to appeal to every point of view, and you’d have to win over a majority of the population on some level to get in. And here’s the thing that a lot of people don’t understand: even if you had the exact same humans in office, their incentives would be dramatically better. Because instead of, “If I go against my party, then I lose my job. So I better just shut up, and do whatever the party says,” then it’s like, “If I decide to exercise some independence, as long as the majority of my district thinks it’s sound, then I can keep my job.”

Andrew Yang: So even if you end up with the same person, if you have a different incentive structure, then you’d see better governance, better independence, and, by the way, less authoritarianism. Because you know that in the Republican party, they’re essentially two parties right now: there’s the Trump Republicans, and then the moderate Republicans who secretly wish Trump would go away. And so, if you unlock their incentive structure, you would see many more of them act like Senator Murkowski did, where it’s like, “Look, I don’t love this guy.” And then they’d have a chance to come back in, because a majority of voters across the board agree with them. Not a majority of Republicans — which is who they’re beholden to right now — but a majority of all voters.

Approval voting vs. ranked-choice voting [00:19:51]

Rob Wiblin: I know a bunch of people who are also working on ballot initiatives in order to do voting reform at the local and state levels in the US. We actually interviewed Aaron Hamlin, the founder of the Center for Election Science, a couple years ago. And he was doing a similar thing, but he was trying to get up something called approval voting — where basically you just get to say “yea” or “nay” to every candidate that’s running. What do you think of approval voting as against the ranked-choice voting?

Andrew Yang: I love approval voting. It’s great. And I’ve seen arguments where it is better than ranked-choice voting in some situations. I looked at this, and said I’m going to push ranked-choice voting because it addresses the problems that I’m most concerned about with polarization. But it also has a bunch of wins already, where it’s been used in 50 cities around the country, including New York City. There are organizations that have been deploying it. It’s going to be tough to change the voting system in the US, so you might as well use a system that at least has some traction in the world. But all that said, big fan of approval voting.

Rob Wiblin: Approval voting would be way better, as well.

Andrew Yang: Yeah, yeah. The plurality voting system is terrible. It’s so dumb.

Rob Wiblin: It’s the worst. What’s the point? It’s just —

Andrew Yang: Yeah. If someone were to push for approval voting or STAR voting, I’d be excited about them. I just think that RCV has more momentum, more traction. It gets rid of the spoiler effect. It allows for moderation. It has a better chance of success in the immediate term.

The worry that third party candidates could cause harm [00:21:12]

Rob Wiblin: Speaking of the spoiler effect, when I asked the audience for questions to put to you, a lot of people were really worried that you might run for president in 2024 — or the Forward Party might put forward another candidate — and basically you would end up sabotaging whoever is most similar to you in terms of policies or style, because of this spoiler effect that the plurality vote creates. Are you basically going to wait until there’s some voting reform before you start running candidates in elections, if it doesn’t seem like you’re in the top two or three?

Andrew Yang: We need to race towards ranked-choice voting or some other more modern voting system that allows for different points of view to emerge as quickly as possible. And I, personally, am a little bit saddened by how everyone is just scared about the spoiler effect, because that’s the cudgel that the duopoly uses on everybody really. It’s like, “We’re going to do something different.” — “Oh, you’re going to mess it up. You’re going to mess it up.”

Andrew Yang: Well okay, in theory, does the Democratic Party not control the levers of government in at least half of these areas? If you’re genuinely concerned about the spoiler effect, why don’t we just change it to ranked-choice voting? You control your own elections. You certainly control your own primaries. But you control the mechanics in many of these states. And so that, to me, is a solutions-oriented approach. It’s like, “You’re concerned about the spoiler effect? Let’s solve it.”

Rob Wiblin: So I guess to some extent, it could be used as a threat that you’ll run, and other people will run, and they’ll create this spoiler effect, making the election a bit of a nonsense — unless people go and actually reform the election. So let’s go do that.

Andrew Yang: That’s one of my arguments, Rob, is that if I were to just push, push, push and be like, “Are you concerned about it? Fix it, fix it, fix it.” Then it has a better chance of being fixed than if we’re all like, “Everyone stand still until they get around to fixing it.” Which by the way, they never will.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. I can see that argument. I would hate to see Trump elected in 2024 as the implementation of that threat though. It seems like a very high price to pay to me.

Andrew Yang: And this is something that I think — at least I hope — people sense about me, is that I’m a rational dude. I’m not going to do something irrational.

Rob Wiblin: You’re not going to do something really stupid. Yeah. I suppose there are a lot of opportunities to put up these ballot initiatives for voting reform. So maybe the first line of attack can be doing that: getting money and then running those campaigns everywhere that’s possible. And then the Forward Party —

Andrew Yang: 2022. We’ve got one cycle to try and make some enormous headway. So if you’ve got a billion dollars and you want to fix American democracy, you genuinely could. The entire investment in this area right now is $153 million. It’s way too low. It’s stupid.

Andrew Yang: This is something that I also find frustrating. To the extent that there’s something I can do to help, it should be this. Out of all the money that’s getting spent on a lot of things, don’t you think preserving American democracy and making it more resistant to authoritarianism is probably worth a billion bucks or more? It’s probably worth $100 billion. It’s just that, for whatever reason, philanthropists aren’t seeing this.

Andrew Yang: And, by the way, none of the political incentives of the media organizations are around this. $2.65 billion was spent by the two parties in the last cycle alone, just on the congressional races. And then $153 million is getting spent on actually fixing the underlying system. Of the $2.65 billion, the vast majority of the money canceled each other out, because they’re just using it against each other.

Rob Wiblin: Whereas you can actually pull the rope sideways a bit by shifting how the system works.

Andrew Yang: Yes. So if you’ve got the money, let’s freaking do it. Reach out to me and we’ll put the money to work. But this isn’t hypothetical, you know what I mean? This is one thing I want to push as well. I want to help create positive visions for the world we can live in. But I’m also a parent who’s concerned about the world my kids are going to grow up in and the rest of it. Shit’s going poorly. We have to go fix it, because the people who are listening to this podcast are among the more likely people to fix it.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah, yeah. I think we’re going to have some more episodes on voting reform in the next year or two, so listeners should stay tuned for that.

Investment in existential risk reduction [00:25:18]

Rob Wiblin: Shifting gears a little bit: on this show we regularly talk not only about ways that things could go super well, but also ways that the future could go really badly. And the classic list of worries are climate change, as you were saying; and also artificial intelligence advances gone really wrong; biotechnology advances being used for harm through weapons or otherwise or through accidents; a war between nations — especially one involving nuclear weapons — could just completely ruin everything.

Rob Wiblin: On a recent episode with Carl Shulman, the public thinker, he pointed out that using standard cost-benefit analysis, you could justify enormous efforts to prevent catastrophes from those causes and others. Because, say, a cumulative 1% risk of everyone in the US dying from one of those events — which seems more likely than 1% to me over the next century — that would be worth spending up to $13 trillion to avoid, just from the perspective of American lives saved, just using the standard way that the government analyzes the value of lives saved. It seems like it would cost much less than $13 trillion to reduce the risk of that by one percentage point over the next century.

Rob Wiblin: So yeah, do you think we underinvest in avoiding or preparing for those sorts of tail risks — you know, low-probability events that would be super catastrophic if they happened?

Andrew Yang: Of course we do. I made this argument on the presidential trail. I went to crowds in New Hampshire and Iowa and I just asked them this: “How much do you think climate change is going to cost us?” They think about it. And I was like, “Look, the economy is $22 trillion, just so you have a frame of reference. What do you all think?” And they came back with very big numbers. And I was like, yeah, it doesn’t even include all the human lives that are going to be lost.

Rob Wiblin: Just lost GDP.

Andrew Yang: Yeah. You could justify tens of trillions of dollars in investment easily in trying to prevent climate change — and that’s just in the US. And again, one reason I love this community is that if you think about it species-wide, then all of a sudden of course all of these investments become not just sensible, but extraordinarily necessary and rewarding. It’s just that’s not where political incentives are. And if there was an American political leader, like, “Hey, guess what we’re going to do? We’re going to spend a ton of money on these far-reaching problems and whatnot.”

Andrew Yang: It’s like a disease that’s born of the political equivalent of our stock market moving back and forth. It’s like, how long is the news cycle? 24 hours, less nowadays. How is your performance evaluated? Quarterly at the longest. So who’s rewarded for thinking that long term? No one in American politics. So they just don’t do it.

Rob Wiblin: An incredible example of this is how the US spent trillions of dollars responding to the damage of the pandemic — economic stimulus, trying to make people whole, and undo the damage that was done by people having to stay home. I think it was like trillions of dollars spent on the CARES Act, but they’re currently kind of bickering whether to spend $30 billion advancing the technologies that would arrest and stop the next pandemic, and do all of the preparation that we should have done last time so that we didn’t have such a disaster. And that’s about 1% or 2% of the amount of money we spent — and that’s just the money, let alone the lives lost. The desire to always be reactionary rather than getting ahead and thinking about how we can stop the damage in the first place is crazy to me.

Andrew Yang: Yeah. It’s not great. And the conclusions I’ve drawn about the system, Rob, really are that the duopoly is going to kill us, and that the two sides don’t really care about getting it right — they just care about eking out the next win. And they just trade power back and forth in DC while we all sink into the mud or get sick with the next pandemic or suffer from climate change. The institutional incentives are all wrong, and the world will just continue to suffer as a result.

Andrew Yang: It’s why I think there needs to be a genuine political restoration and complete rejuvenation of the system. This duopoly is just awful. You know what I mean? They’ve been trading power back and forth for 160 years or so. And the faith in the system is just going lower and lower. You see with Trump winning, 62% of Americans want an alternative to the duopoly even now. And then if someone actually suggests an alternative to the duopoly, then everyone’s like, “Oh no, you’re going to screw it up for the good guys against the bad guys” — whoever that happens to be.

Rob Wiblin: You’ve talked more about tail risks than the great majority of people in public life over the last couple of years, but it’s not something you talk about all the time. Is that just because it’s something that people don’t want to hear about so much? It’s hard to get people energized, and you’re maybe suffering through the same thing that all of the other people in politics are, which is that people want to hear about the problems that are right now, not thinking about how to prevent the problems of the future.

Andrew Yang: Well, it’s one reason why I love UBI, because it’s a problem of right now, and also helps pave the way for a brighter future and meets everyone where they are. I think to the extent that this discussion has generated a ton of energy, it is around climate change — young people who stood up and were like, “Look, you’re destroying my chance for a decent life.” Which some people take as dramatic, but then you think about it and you’re like, well, it’s probably right.

Rob Wiblin: I wonder whether that’s got a renewed bunch of interest lately? At least my perception is that people are talking about climate change much more than five years ago. And I wonder whether it’s because we are on the cusp of having the solutions. It doesn’t feel as hopeless as it did, and people are excited. It’s like, it just doesn’t cost that much money to put up solar panels. Maybe we should do it, climate change or no.

Andrew Yang: Yeah, it’s true. The technology’s gotten better by leaps and bounds. And so it does seem more immediate for people to do the right things.

Future generations as a disenfranchised interest group [00:30:37]

Rob Wiblin: We’ve been talking about voting reform. Do you think from a voting perspective or from a societal decision-making perspective, it’d be reasonable to think of future generations as kind of a disenfranchised interest group? Because they don’t get to vote, they don’t have any kind of direct influence over our politics — but our decisions today through climate change and all sorts of other issues can potentially have a huge influence on their wellbeing.

Andrew Yang: I love it. There should be the unborn generations lobby where it’s like, “Hey, we don’t exist yet, but you’re totally screwing us.” You don’t even need to wait for the hypothetical — frankly, it’s young people in the US too. They look up and they’re like, “Hey, you all are screwing us.” Because in America, you can see we have a gerontocracy. There’s also a circular thing where young people don’t vote at the levels that old people do. Little-known fact — I mean, maybe you know — but I won the Iowa youth poll. So if it was just young people, I might be the president today, but then when it got to old people, I did much worse.

Rob Wiblin: Interesting. Yeah, I think Wales and Scotland have recently created commissioners for future generations. So I think when they pass new legislation, the commissioner can comment on what impact this will have on the unborn — whether it raises or lowers their wellbeing — and the government’s meant to consider and respond to that. Seems like it’s kind of a small step in the right direction of taking seriously these billions of people who we’re going to have impacts on.

Andrew Yang: I love it. I wish there was a future lobby here in the US.

Humanity Forward [00:32:05]

Rob Wiblin: What’s the most important thing that we could maybe do — other than the things we’ve already talked about with the voting reform — to try to get policy formation to better reflect the interests of people who will be alive in 50, 100, and 150 years? Is there anything cheap and easy that might help to put this more in people’s heads?

Andrew Yang: Yes, I think there is. So check it out: I ran for president and then after my campaign ended, I started a 501(c)(4), Humanity Forward, that has now become a lobbying firm. So believe it or not, there is actually now a DC lobbying firm on behalf of humanity. And what are the issues it’s advocating for? Basic income and cash relief, democracy reform, sensible cryptocurrency regulation. I don’t know how people feel about that on this podcast — that you don’t want to like, kill the crypto industry.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. I’m a modest crypto skeptic, but it should be given a fair shot to change things. And it’s quite frustrating to see it kind of being killed in the crib a bit.

Andrew Yang: Yes. A carbon tax, I don’t know how people feel about that particular policy, but we have a real-life lobbying firm with a budget in the low millions right now. It’s punching way above its weight class because when they meet with congressional offices, they’re very benign: they’re just giving them data, being like, “Hey, cash relief is popular in your district. Here are some of the stories, here are some of the people and the members’ office.”

Andrew Yang: Because if you were a congressional policy staffer or whatnot, and you were dealing with like a Humanity Forward org that was just feeding you positive information about things, that’s a hundred times more pleasant than dealing with the tobacco lobby or the financial services lobby, where they’re like, “Hey, change this rule, do this, don’t change this rule. It’s going to hurt us.” And then you’re like, “All right, all right, all right.” Then Humanity Forward comes in like, “Hey, some of these things would be really good for people” and you’re like, “Oh, cool.”

Andrew Yang: So when you talk about something that we could do to actually get this in front of policymakers, I’m super excited. Of the things I’ve done, I am perhaps most proud of Humanity Forward — that we have professional lobbyists. Because if you’re standing outside chanting and screaming, it doesn’t matter. You know what I mean? At this point it doesn’t matter. But if you manage to make it seem like it’s going to help people stay in office — it’s going to be politically advantageous, and it’s going to help people too — then they’re like, “Okay, I can do this and it actually serves my goals.”

Andrew Yang: So if you want to help on that front, you can check out humanityforward.com. It’s a 501(c)(4). And then we also have a 501(c)(3) foundation that just has cash relief pilots and then tells people’s stories. Can you believe that we have these benign things?

Andrew Yang: People think about me in the Forward Party and democracy reform right now, Rob, but there are four legs to this stool I’m trying to build. Leg number one is this lobbying firm, Humanity Forward. Leg number two is the (c)(3), which is a foundation. Leg number three is the Forward Party as this political movement that most people now associate with me. And then leg number four is going to be a media organization that tries to put out some of these messages. So, you know, working on it.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah, yeah. Congrats on getting that going. It seems like there might be a lot of opportunities where a lobbying firm can think of something that’s both in people’s political interests that would also be really good for future generations. They’re trying to thread that needle.

Andrew Yang: Yes. Exactly. That’s the jiu jitsu involved, Rob, where we just got to go to them and be like, “Hey, this will help you. And oh, by the way, it will help future generations grow up in a world that’s not burning.”

Rob Wiblin: Double win. Equally important issues, equally important issues, Andrew. It’s great that that exists, but my worry might be what if people lose interest over time, and it’s hard to really sustain the funding at the ideal level? And I imagine already you would want it to be much larger than it is.

Andrew Yang: Yeah. Right now it’s got a budget of several million a year, which is way too low — it should be in the tens of millions. But I’m still very proud, because even at our current level, we’ve done a lot of really awesome work. For example, the Child Tax Credit is going to be continued for at least another year and that’s an enormous anti-poverty win.

Rob Wiblin: One institution that the US has — which helps to bring some sense in thinking about long-term impacts of policy making — is the Congressional Budget Office, which helps to analyze the long-term budgetary implications of different policies, and helps to bring some numbers and reality to people’s thinking. I wonder whether we should have a similar organization that looks at policies and tries to forecast what impact this might have in 50 or a 100 or 150 years’ time? What will future generations think, looking back on this policy that we’re making?

Rob Wiblin: And it might just not turn out the obvious stuff, like we should be doing more about climate change — an analytical office like that might find that we’re radically underinvesting in biotechnology research or biomedical research. Because for future generations, we can make these advances that will make their lives so much healthier and so much better. And that’s one way that we’re neglecting to benefit them, is not putting enough in science and tech now.

Andrew Yang: I like that too. It’s like the future CBO.

Rob Wiblin: Exactly.

Andrew Yang: The CBO from the future comes in and says, “Hey, you’re underinvesting in regenerative agriculture.” Which we are.

Best way the rest of the world could support the US [00:37:17]

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. You focus a lot on US politics, and get asked all the time about what America should change. But about half of our audience is in the UK, EU, Australia, New Zealand, India. What’s one thing you wish other countries would do to support the US in making the world a better and safer place?

Andrew Yang: Gosh, I mean, from the outside looking in, you must be like, “What the hell’s wrong with you people?”

Rob Wiblin: No comment.

Andrew Yang: Well, this is the great insight of my book that I discovered: that the American system is set up to fail. That’s why I’m now so determined to try to change that. From the outside looking in, I mean, I feel like you all can hopefully just continue to serve as examples of systems that are more resilient and doing things well. Certainly I would love to move to a more multi-party parliamentary-type system in the US. And I wouldn’t be so naive as to think everyone else feels like, “Oh, we’ve got it all figured out.” So as long as you just keep on doing well, that’s a big win.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. It’s interesting. I was reading a research post on the Effective Altruism Forum last week and it was saying that maybe people had underestimated how useful it is to get up new policy ideas and new governance systems in small countries like Switzerland or Sweden — or even the UK or Australia to some extent — because if they work out as people think, then people notice and they can be copied in progressively bigger countries and bigger situations. So the direct impact of changing something in Sweden might be small, but then the demonstration effect could be quite large — and that could end up being the dominant one.

Andrew Yang: I love it. I try to take ideas from other countries every chance I get. Jonathan Haidt said recently the worst number of political parties you can have in a country is one, but the second-worst number is two. And so one example I say is that Sweden has eight parties — that seems better. So if Sweden has another program that’s also working, you can be like, “Look! Look what they did.”

Andrew Yang: Though, unfortunately, in the American political environment now, any example you use ends up being politically loaded or freighted. So there are a lot of Americans who, if you said Sweden did something, they’d be mad. They’d be like, “We don’t want to be like the Swedes. Those accursed Swedes with their socialist tendencies and their caring about families.” No, I mean, I’m only half kidding.

Rob Wiblin: You have to choose a country like Greece where people are like, “Is Greece red or blue? I don’t know. I’m confused. Maybe we could do whatever Greece did.”

Andrew Yang: Yes. Yes. I need different examples for different people. It’s true.

Recent advances in AI [00:39:56]

Rob Wiblin: Let’s talk about advances in artificial intelligence for a bit. Back in 2018, seeing how technology was causing a lot of people in America to kind of permanently tragically drop out of the labor market was one of the reasons that you decided to throw yourself into politics in the first place. And during your presidential campaign in 2019, you talked a lot about your concern that rapid improvements in artificial intelligence could potentially displace a whole lot more workers from their jobs in coming years at a faster and faster rate. Since then, has that process progressed faster or slower than perhaps what you were expecting?

Andrew Yang: It’s been uneven. Some of the things that I was most concerned about, you could probably lengthen the time frame — for example, limo drivers or truck drivers. And then in some other areas they’ve invested more in it more quickly because of COVID, where people have been staying home more. Retail has been transitioning in different ways and they’re automating a lot of, for example, the cleaning jobs at Sam’s Club, or even the meat packers at Tyson’s Foods. So it’s been heading in different directions in different parts of the economy.

Andrew Yang: I think the general concern is still very, very pressing. Over half of companies reported investing more in automation technology over this last year and a half as a result of COVID. So you know it’s coming. One of the examples I use that everyone can understand is that two million Americans answer phones for a living and Google’s AI can do that probably today. So it’s picking up steam, even if some of the industries are not being impacted as quickly as some might have feared, myself included.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. I find myself in an interesting spot on this question, because I think in the long term, or even the medium term, I’m with you: I expect there to be some period where we see job displacement pick up and happen faster than at historical rates. But if I look at the economic data right now, it seems like people have always been getting displaced from jobs due to technological change and other social changes, and it seems like it’s at roughly the same rate that it has been historically. So it seems like there’s advances in AI, but maybe they’re happening at a similar rate to previous changes. But in the long term, I think there will be this change, and we should be preparing for when that happens. And we don’t know when it will happen — it could be five years, could be 15 years, could be 25.

Andrew Yang: Well, Rob, I’m just going to throw one thing out there that is empirically true, which is that the American labor force participation rate just keeps on going down and down. It’s one reason why people here are losing their minds. So you can cast about for any number of explanations for that. But right now I think that has to be the clearest marker of where we are, and you could say maybe that’s not AI and automation, maybe it’s other things — there are a lot of things combined. But every 10th of a percent of the labor force participation rate dropping in the US is hundreds of thousands of people leaving the workforce, and I just want people to think about what that means in those households. You know what I mean? Or communities. I mean, there are all these people that are dropping out, and it’s hard to get back in. And I believe that’s driving a lot of the cultural and political issues as well.

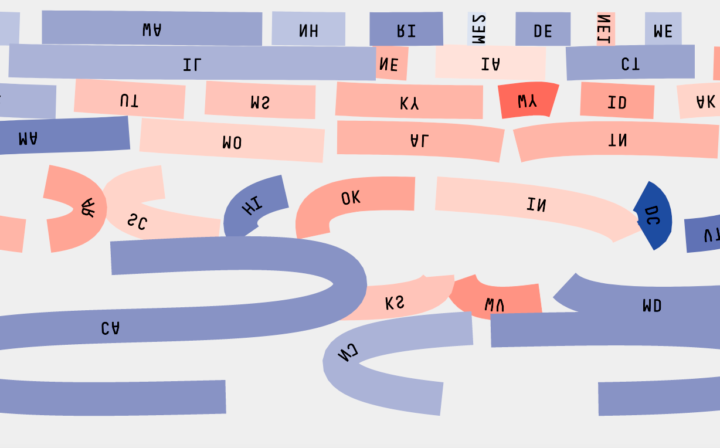

Rob Wiblin: I’m just taking a look at the labor force participation rate here. It seems like it was slowly declining from 1995 to 2008 and then it really started going down — which I guess the financial crisis just created these potentially very long-lasting things. And then surprisingly, despite quite a booming economy, it was fairly flat from 2015 through 2020, which is interesting. I think wages were starting to go up there and the labor force was reasonably hot, but it’s interesting the labor force participation rate wasn’t returning, which is kind of consistent with your story that there’s structural challenges.

Andrew Yang: Yeah. There’s the structural challenges and people are not getting dragged back in. And then what happened from 2020 to now? I don’t have the graphic in front of me so I’m curious.

Rob Wiblin: It obviously plummeted during COVID, and now it’s recovered maybe half of the way to where it originally was. I think it lost almost two percentage points and now it’s one percentage point back. So yeah, fingers crossed in coming years we’ll manage to get almost all the way back, or all the way back up.

Andrew Yang: Yeah. So that is the concern. If you’re still 1% down in a workforce of 200 million — that’s like two million more people. So that’s the stuff where if you look at it, you could say, maybe it wasn’t AI and the rest of it. But it’s happening. And a lot of those jobs were retail jobs, or jobs that catered to folks who were working in urban downtowns. I just heard that in New York City, only 8% of workers are back in the office five days a week. And that’s even now when it’s moderately safe to do so — so you can imagine the effect that’s having on urban retail.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. It seems like with machine learning and artificial intelligence research, the state-of-the-art science there is really impressive — it impresses me on a regular basis. But I suppose that the transition of that science into actual products and into the workplace can be quite a gradual process. It’s possible that perhaps some structural weaknesses in our ability to apply new technology is helping to give us some breathing space by slowing down how quickly people are getting displaced. Because it just does take a long time to figure out how to get them to work in an actual customer situation.

Andrew Yang: Oh yeah. Like if you’re a mom-and-pop restaurant, you’re not going to robot any of it, you know? You have some freaking like, cheap kitchen staff and the rest of it. I mean, I’ve run small businesses, so even while I’m talking about technology writ large, I know that the average firm might not be adopting this stuff. The problem is that you have the folks who have the highest level of financial resources and incentives who will adopt this stuff. And in some cases it’s going to suck for a while too — they’re just, “Oh, this thing stinks,” but then they’ll get it right and they’ll get all these competitive advantages as a result.

Andrew Yang: I’ll share with you a story. I was talking to a friend who works in private equity. They bought a fruit drink company — they juice things, like bottled juices.

They had warehouses and manufacturing facilities full of workers, many of them migrant Latino workers. And then they made the switch during COVID to juicing robots — before, they had all these people in there, and then now they have juicing robots. And it stung for a while, the transition stung, but now they’ve got it down. They’re loving it, and they use 80% fewer workers and the rest of it.

Andrew Yang: So is the average juicing company doing that? No. But is there going to be some leading company that —

Rob Wiblin: And then everyone else copies.

Andrew Yang: Yeah, or they’ll end up squeezing them out. Look at that, there’s a pun: “squeezing them out.” But that’s the American kind of winner-take-all system at this point: if you can get an edge, then you can apply it across a bigger and bigger part of the industry.

Artificial general intelligence [00:46:38]

Rob Wiblin: So it seems like the story that you and I both believe is that sooner or later, it’s more likely than not that there’s going to be really big changes created by AI advances. And that’s not just what we think — lots of people think that. That might even be the default position. It seems like that view is that AI systems are likely to become capable of doing many things at the human level relatively soon, such that they can substitute for lots or possibly even most jobs in the economy sometime soon. In that AI technology world, it’s going to be broadly capable and able to outthink humanity in many domains.

Rob Wiblin: But if AI is able to do that, wouldn’t we expect the effect on society to be even more revolutionary than just a lot of people losing their jobs or big changes in the workplace? I mean, we would likely in that world be in the process of handing over the reins of decision-making on all kinds of important decisions. The ability to run all kinds of different processes to this other species of machine intelligence, in a way it’s an even bigger historical moment — potentially that calls for thinking about more than just the labor market.

Andrew Yang: Yeah. There are some very big changes afoot. And again, there are going to be some very sophisticated organizations that take advantage of these technologies before anyone else. And because they’re going to be at the top of these billion-dollar, trillion-dollar firms, then you’re going to see an incremental improvement result in tens of billions of dollars of value. So this is something that I think we should expect, especially because a lot of what’s fueling these AI algorithms is just data. If you’re Amazon, you just have much, much more access to more data. And so it compounds, you know what I mean? It will compound on itself.

Rob Wiblin: So there’s going to be big technological changes, and you made that real for people, and made it a practical question by talking about universal basic income. But I wonder whether now that so many people are on board with that and have accepted that, it might be time for you to run ahead of the discussion again and say, “It’s not only about the labor market. It’s about a huge transformation — like the biggest transformation in society we might ever see could happen in the next century.” Because you’re a great communicator, you can get ahead of where people already are, and get people thinking bigger picture about how the future could just be really wild. And we need to have some ideas in mind for how we’re going to manage that transition with artificial intelligence, and with other technologies as well.

Andrew Yang: Amen, Rob. I’m happy to do that. My new gear is trying to get us past this duopoly that I think is designed to fail us. Actually it’s designed to make us insane first while it’s failing us, and turn us against each other and generally have it devolve.

Rob Wiblin: Possibly it limits the conversation.

Andrew Yang: Yes. It does limit the conversation, and there’s no real accountability. So I’m with you. If there are things that I can end up communicating — I now see this as my role in American life: to try and convey a sense of what’s coming to enough people. Joe Rogan called me “the Paul Revere of automation.” And I was like, “Oh, that’s nice of him.” So hopefully I can do the same thing for some other big ideas beyond democracy reform.

The Windfall Clause [00:49:39]

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. Well, let me throw one at you as a way of making this real and practical in the way that the UBI did on the labor market side. As you know, there’s two really well-run and well-resourced organizations whose explicit goal is to develop artificial general intelligence that can try to tackle almost any intellectual problem — that’s OpenAI and Google DeepMind. Experts think they have a good shot at succeeding — might be 10 years, might be 50 years, might be 100 years. Things could go slower or faster, but it could be a really big deal. And there’s this idea floating around that it’s possible that the company that invents an advanced general intelligence — either the software or the necessary hardware — could, as you’re saying, own hundreds of thousands, trillions of dollars in profit, because they would just have the key to unlocking untold amounts of productivity.

Rob Wiblin: And one proposed solution to that is called the Windfall Clause, under which AI companies, and maybe any kind of company, would commit to give away all of their profits beyond some very high point — say, 100x return investments. So they can earn 100x what they put in, but beyond that, the return should go to the general public along some lines — potentially universal basic income, I suppose. What’s the meme? It’s “Fully Automated Luxury Gay Space Communism.” Basically a company shouldn’t be able to grab all of these resources — it should be that the cornucopia should be distributed more broadly. Do you have any thoughts on that?

Andrew Yang: Yeah, I’m very much for a measure like that. One of the things I was arguing for was an AI tax, an AI VAT — something that harnesses the gains. And the example I use for people is if Google’s AI can do the work of two million call center workers, how much is Google going to pay in taxes on that? And then you think about it. It’s like, well, Google doesn’t seem to pay meaningful taxes at all. And I know OpenAI, I think it’s like… They’re wholesome. So if they do come up with this, they would like it to be something that benefits not just a couple firms — they’d want it to benefit the public.

Rob Wiblin: OpenAI is committed to some form of the Windfall Clause basically in their structure. There’s only so much money they can make before they have to give it away to people.

Andrew Yang: Yes. So I’m very much for this Windfall Clause and I’m grateful that other people are already committing to some version of it. Thank you, Sam Altman!

Rob Wiblin: Unfortunately I can’t remember the name of the author of this paper. I think it was from the Future of Humanity Institute, but it’s about the Windfall Clause. We’ll stick up a link to it so people can check it out. The Windfall Clause is maybe a voluntary agreement, but as you’re saying, in a world where AI is doing so much of the work, we would need to rethink the tax system. We have a tax system now that’s designed around most people earning a labor income.

Andrew Yang: We should not be taxing human labor in the vast majority of cases. You tax things you don’t want more of — you want more labor. This is one of the things I’m passionate about. You see the declining US workforce, which has disastrous social and cultural effects. And so I would want to rethink our tax system.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. Oh yeah. I suppose academics don’t like to think about things that seem speculative and strange, but it could be a very interesting open question: in a more AI-ish economy, what does standard tax theory say about how we ought to extract some of that so that we can distribute it and everyone can have a good life? So yeah, good economic sense.

Andrew Yang: That is one of the big questions. Let’s do it. Let’s get that AI tax in and then enable luxury subsistence, gay space, whatever —

Rob Wiblin: Fully Automated Luxury Gay Space Communism, yeah. Or at least social democracy. We’ll stick up a link to your AI tax idea.

The alignment problem [00:53:02]

Rob Wiblin: I know that you tweeted back in 2019 when you spoke with the Oxford philosopher Nick Bostrom about the possibility of AI advances going more seriously awry, because we fail to align AI with the values that we have — and so they go off and pursue goals that we never would’ve wanted them to pursue. Have you spent much time thinking or learning about that possible risk scenario since then?

Andrew Yang: Not as much as I’d like. I’ve spent some time with Kai-Fu Lee, who’s one of the thinkers on this. I think our expectations in this space should be negative. What do I mean by that? Our expectations should be negative in the sense that you have a competitive dynamic, where people are trying to come up with better AI and better applications and it’s often wedged in a firm. And so you should expect this to exacerbate inequality in various ways, because that’s just the way the market dynamics will play.

Andrew Yang: And I’m a little bit less concerned about — and some people beat me up for this or disagree — the singularity and the other big macro issues. To your earlier point, if there’s a minuscule possibility of something that’s species-threatening, then you should take it very seriously and invest trillions of dollars in it — I totally agree with that. So I’m very, very grateful that there are people that are working on it.

Andrew Yang: I guess when I say we should have negative expectations is that at this point, you’re seeing so many failings and failures. I do have a higher confidence level in some of the AI organizations — I know some of the people. I have low estimation in government, which I think is one of the prerequisites to what you’re describing. People talk about sensible adoption or guardrails and whatnot. And a lot of my mind goes to like, who the hell’s providing these guardrails? The government? The government doesn’t understand the stuff at all. Doesn’t care for the most part, because it doesn’t get them a press cycle. So that’s why I’d be concerned about it: I don’t expect our governments to be on the ball on this issue.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. I can totally see how you would be pessimistic, given that you’re working in politics the way you are. I feel a little bit more optimistic, because I see it’s so broadly accepted that there’s technical engineering challenges here that have to be addressed at some point before we can be handing over really important decision-making procedures to AIs, and we need to fix some of the issues that we have with AIs that are already deployed.

Rob Wiblin: And it’s also very broadly accepted that there’s big social, economic, political, and international relations issues here. A lot of people I meet are really excited to get into this space and figure out how we manage this potentially very big transition, whenever it happens to reach us. So I don’t know, I see a lot of seriousness and a lot of really smart people going into it. But it’s true: actually implementing the things that they learn and figuring out what works through experimentation can be challenging — especially when you have a government that’s not super responsive, even to challenges that we’ve known about for decades.

Andrew Yang: Yeah. And this relates to something I mentioned earlier, which is that the US in particular has an unaccountable gerontocracy, and they don’t understand these issues for the most part at all.

Rob Wiblin: That’s interesting.

Andrew Yang: I mean, the folks that have been in power in DC have often been there for 20, 25, 30 years — they might never have checked their own email, even as an adult. Some of our leaders are my father’s age. My father’s 81, Nancy Pelosi’s 81.

18-year term limits [00:56:21]

Rob Wiblin: Something you’ve talked about a bunch recently is potentially having an 18-year term limit for serving in Congress, and then an 18-year term limit in the Senate in order to try to get a bit of turnover, a bit of fresh blood.

Andrew Yang: Yeah. That would be a game changer, that alone. I think that’s the right balance. And I even have a clever way to adopt it, which is you could grandfather in all current legislators, so they’re not voting themselves out of office.

Rob Wiblin: So they don’t oppose it.

Andrew Yang: Yeah, so they don’t oppose it. But eventually they’d age out and you’d wind up with legislators who showed up and then were like, “You know what? I’m out of here anyway. I might as well do something.” Plus their average age would be much lower than it is now. The average US senator is 64, member of Congress is maybe 57, 58. But the leadership, the average age is literally 75 and up.

Rob Wiblin: I feel a bit torn on this, because I think there really is value in the experience and the knowledge base that is built up among people who are older. But the thing that’s a bit unfortunate is I feel like we don’t have the right mix. It’s like, you want some people who are in their 50s, somewhere in the middle; people who’ve been around for a very long time, a few people in their 70s; some people in their 20s who are abreast of the new things that people who are older haven’t thought about. And it just feels like the mix isn’t right.

Andrew Yang: Well, another weakness of the current system, you have Chuck Grassley and Dianne Feinstein who are running for office at the age of 88. People are literally just going to expire in office, because there’s no process or incentive for them to do otherwise. But when you talk about a mixture, if you had 18-year term limits, there’s nothing preventing someone from getting elected into office at the age of 55, and then being there until they’re 73. So you’d wind up with a mix of people like you’re describing.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. I have mixed feelings about term limits. I absolutely see the case that you’re making. I feel like the smartest objection that I hear is that in a world with term limits, it empowers lobbyists and empowers external actors, because they’ll have all of the expertise, because they stick around all the time. Whereas the politicians themselves will always be turning over and they’ll always feel like freshmen — they don’t really know what’s happening, they don’t understand the process. So they’ll always be asking lobbyists for advice. I feel like 18 years maybe is a bit in the sweet spot where there’ll be enough people who do know.

Andrew Yang: Yeah. That’s why I chose a slightly longer term, because of that concern. I talked to someone in DC the other day, where the concern you have is very much with us now — the level of resources available to lobbyists is much, much higher. Like members of Congress are one thing, and then their staffers — they’re just rotating out all the time now. If they go to the other side of the lobbying firm, they’ll get three, four, or five times their salary. And so if you work in a congressional office now, you’re overworked, you’re underpaid, everyone’s always mad at you. And so then you’re like, “Okay, what is my next step?” And then the lobbyists on the other side are like, “We pay better. Your lifestyle is better. You get more respect.”

Andrew Yang: And that is DC in a nutshell now. So if you are concerned about there being a mismatch of resources, it’s already here. But I’m with you, that you need a longer term limit, because you can’t just have people show up and be clueless and then leave.

Rob Wiblin: Kick them out after two years.

Andrew Yang: Yeah, but someone said to me, “Oh, you need a learning curve.” It’s like, what learning curve takes more than 15, 16 years? What, it really clicks in at year 22?

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. Well, just wrapping up on AI, I’m really excited that you’re interested in all these different angles on AI. There’s the labor market side, but there’s also potentially larger changes in how we make decisions as a society, as well as the unlikely but very severe risk scenarios that also deserve some attention just on expected value grounds. And I think there’s a lot of ideas coming out of this space, a lot more concrete suggestions for what to do that hopefully you’ll be able to engage with in years to come.

Andrew Yang: Well, you know what? It’s been great for me to have this conversation, because it makes me think that we should make this part of Humanity Forward’s lobbying mission. I mean, it’s rare to have a professional lobbying shop that’s dedicated to the public good the way that we are. Because if you think about most of the lobbying groups, they don’t really resemble that. So we should make the incorporation of AI into society one of our priorities.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. If you’re interested to learn more, I think maybe the best shop out there, or the people you might want connect with to get the best white papers and the best people to hire for that, or the best advice on what to recommend is the Center for Security and Emerging Technology — a really good outfit in DC that’s taking these ideas seriously.

Andrew Yang: Love it.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. Kind of across the board, thinking about how does society adapt to things that are coming down the pipeline in science and tech.

Andrew Yang: I love think tanks. Think tanks are fun.

Effective altruism and longtermism [01:00:44]

Rob Wiblin: Okay. To wrap up over the next half hour or so, we got a huge number of question submissions from the audience, and we’ve added a couple random bonus ones ourselves. Should we dive in and do them rapid fire?

Andrew Yang: Sure. Let’s do it.

Rob Wiblin: All right. “Does Andrew have any opinions about effective altruism or longtermism, if he’s heard about them at all?”

Andrew Yang: I love effective altruism. It’s just trying to use reason and evidence and facts to figure out how you can do the most good. It struck me as so obvious. Huge fan. It’s amazing, effective altruism.

Rob Wiblin: Fantastic. Fantastic. Any thoughts on longtermism?

Andrew Yang: Love it too. I mean, we’re a very short-term society now — we’re just getting jerked back and forth. I’m so glad that someone’s trying to think about long-term issues for humanity.

Persistence and prevalence of inflation in the US economy [01:01:25]

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. “What’s something Andrew has changed his mind about recently?” The audience on this show loves people changing their minds and admitting mistakes and seeing where they were wrong in the past.

Andrew Yang: I have changed my mind recently about the persistence and prevalence of inflation in the US economy — maybe because there has been clear evidence about the persistence and prevalence of inflation. I thought it was primarily supply chain disruptions, and now I’m beginning to think that it’s going to be with us for quite some time.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. Interesting. I’m hoping that it will cool down next year and that maybe this is —

Andrew Yang: Me too. Me too.

Rob Wiblin: — a bit of a burst of consumer spending, but I guess it’s a lot of pressure on the Federal Reserve right now to figure out how to handle this situation.

Andrew Yang: Yeah.

Downsides of policies Andrew advocates for [01:02:08]

Rob Wiblin: “What’s a policy or idea that Andrew is currently promoting, but is worried might actually be a bad idea?”

Andrew Yang: This is kind of small, but I’ve been championing permanently adopting daylight savings time and just sticking with it. And then there were some folks who messaged me about how parents don’t like dropping their kids off at bus stops in full darkness.

Rob Wiblin: I’m a night owl, so I think that one is good for me. I won’t like as much light later in the day, because I’m usually not getting up until pretty late. Maybe we could change the school hours and work hours at the same time.

Andrew Yang: Yeah, maybe. So that was one thing where I was like, “Huh. That’s a very legitimate concern.”

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. Fair enough. Any other ones?

Andrew Yang: There’s some other things I look at where it’s like, frankly, I think it’s my job to argue for the vision in some cases and then accept that the implementation might be a mix. But one of the things about being a communicator or public figure is that you accept that you’re going to try and anchor someone a little bit further along. As an example, I obviously argued for universal basic income, which I still believe in very, very strongly. But then if someone asks me how I feel about the Child Tax Credit, I love it. It’s not what I was advocating, but it’s a —

Rob Wiblin: Close enough is good enough.

Andrew Yang: Or just progress. Progress is good.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. Of the voting reform that you’re advocating, are there any possible downsides or risks with that? Perhaps that you could see by looking at other countries that have different voting systems? There’s always pros and cons.

Andrew Yang: Well, I’ve become convinced that what America really needs is to move towards multi-member districts and proportional representation in a multi-party system. And I know that there are some people that look at the Forward Party and say, “Hey, this process embedded in the current system is not going to result in the multi-party dynamism that we’d hope.” And I see that argument very clearly. I don’t necessarily disagree with it. To me, the question is, “How do we move as quickly as we can towards something that resembles proportional multi-party democracy in the United States of America?”

Andrew Yang: And I’m convinced that open primaries and ranked-choice voting is a realistic thing that we can do that will actually move us in a better direction. Because I do think the Fair Representation Act, which moves us towards multi-member districts and proportional representation, will not pass. And I’m not the kind of person who will just be arguing for something that I do not think has any possibility of passing in the near term. So what we need to do is movement build, implement open primaries and ranked-choice voting in more places, and get more Americans up to the fact that the duopoly is failing us. And then maybe we’ll get enough energy around something like the Fair Representation Act.

What Andrew would have done differently with COVID [01:04:54]

Rob Wiblin: “Hypothetically, if in 2020, Andrew had had the ability to personally direct any part of the US COVID response that he wanted to intervene in and was authorized to spend unlimited amounts of money on anything he thought was a cost-effective way to tackle the pandemic, what would he have done differently than what actually happened?”

Andrew Yang: Well, you referenced earlier, Rob, the $2.2 trillion CARES Act. And less than 18% of that went directly to people and families — it went to institutions and pipes. And there was something that really pained me about saying, “Hey, we need to prop up this organization” — and then trust the organization to convey the salaries or economic benefits through to people. Oftentimes, they did not.

Andrew Yang: Whereas if you look at a place like Canada, they just went straight to the people. They said, “Hey, look, go to this website. We’ll try and make you whole, or 75% of whole, or whatever it is.” The US did this hodgepodge where we used the tax system. Okay, I get it. The pipes were there. It worked for tens of millions of people. It missed massive numbers of people that didn’t file taxes, who tend to be among the most vulnerable.

Andrew Yang: I would’ve had a much higher proportion go straight to people, and then make that interface direct, and let some of the institutions adjust a bit more meaningfully. I’m not saying it should be 100% to individuals, but the balance was way off, in my view. And I think it contributes to the sense of failure really, here in the US.

Andrew Yang: I also think — and this is not a federal issue — but I think the US should have been trying much harder to open its schools earlier. It was not borne out by the public health data that the schools in some places are closed for a year and a half — it was more of a political decision in certain areas.

Rob Wiblin: Speaking of just giving people money directly: there’s been this big discussion about how to encourage people to get vaccinated. And people have tried lots of different methods, a lot of them quite sensible. But something that surprises me is, why don’t we just pay people? Why don’t we just give people a $500 or a $1,000 bonus in order to get it? Because then it’s not that coercive, it’s not that aggressive, but people will do it because they want their $500 for doing their part to end the pandemic.

Rob Wiblin: It’s totally reasonable to pay people for the hassle of it, because it’s socially beneficial. And then people will say, “But the IRS isn’t set up to do this. It would be very difficult.” And I’m like, “Are we setting it up for next time? Are we setting up the systems to do this obvious thing next time?” And no, we’re not.

Andrew Yang: Yeah, I’ve been making the same argument for a while, Rob. Just pay the people. Who cares? It’s like paying them 500 bucks, 1,000 bucks, doesn’t matter. Really, the amount is a pittance compared to the social good.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. Do you have any frustrations with the response from US agencies, like the CDC or FDA or maybe the science groups?

Andrew Yang: Oh, of course. If you read my book, you saw I’ve got a full chapter on what a fiasco the CDC was.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah.

Andrew Yang: So again, I think the frustration in the US really is born of the fact that we have these unaccountable bureaucracies — that if they fail us, nothing happens. There’s a little bit of a song and dance and everyone’s like, “Eh.” And then just move forward and then wait for the next failure, and everyone’s like, “Eh.” And the press doesn’t focus on that form of accountability; it just focuses on the interpersonal drama of the day or what’s on social media.