Should you wait to make a difference?

The issue

One big picture consideration in career choice is the question of how important it is to make a difference now versus later. Here’s the issue: suppose you could either work at a charity next year or go to graduate school. If you work at the charity, you’ll be making a difference right away, speeding up progress. If you go to graduate school, you’ll be investing in yourself and able to have a larger impact later. Which is better?

If you think it’s better to make a difference as soon as possible, the more you’ll value your immediate opportunities for impact. In our framework, you’ll put more emphasis on role impact potential. If you think it’s better to invest and give later, the more you’ll value activities that build your skills, connections and credentials (career capital), and the more you’ll value learning about the world so you can make better decisions in the future (exploration value).

There’s a similar issue with charitable giving. If you have some money, you can either give today, or you can invest your money, which will grow over time, and give a larger amount later. Under what circumstances should you invest rather than give now?

Summary

Overall, we favour investing in your human capital and wealth early, so that you make a greater difference later in your career. Why?

- You’ll be able to find better opportunities to make a difference in the future, because you’ll get wiser and be able to use better research in which causes and careers are most effective.

- Early-to-mid career, most people can make investments that significantly increase their career capital, such as learning new skills, doing a graduate degree and building a professional network. The returns from these investments more than justify the cost of waiting.

Nevertheless, there are a few other reasons to start making a difference now: it will teach you about the world; it will help you find collaborators; it’s motivating; and it will help you build altruistic habits.

So, overall, we suggest that early in your career you mainly focus on building career capital and learning more, though still put some weight on your immediate impact. If choosing between two jobs, this could mean choosing the one that best builds your career capital, using immediate impact as a tiebreaker. As you get older, put more and more weight on your immediate impact.

Read on to see a full discussion of the considerations and our reasoning.

Table of Contents

How we think about this problem

Introducing the model

To analyse this problem, we use a simple model, which we were introduced to by Paul Christiano. Although simple, we think this model captures and explains the key considerations. However, it doesn’t capture all the indirect effects, which we address in the next section.

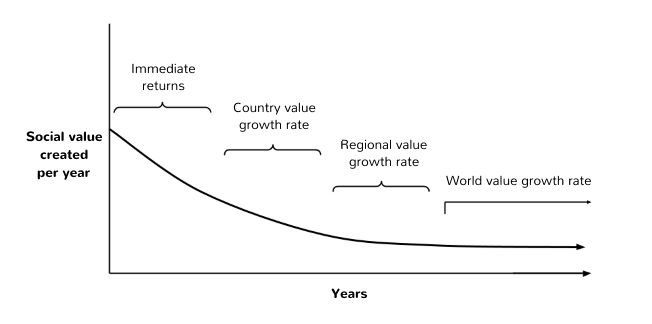

Let’s consider a unit of resources (either labour or money) being spent on an intervention that makes the world a better place, used for example to distribute malaria nets in Africa. Initially, it prevents some people getting malaria – making their lives much better. It also makes these people more generally productive, enabling them to better help their families, friends and the people they trade with, who then help their connections and surrounding society, who then help the people they’re connected with, and so on. At first there’s a relatively narrow impact (fewer people with malaria), but over time, the benefits get gradually spread out.

Once the benefits have spread out enough, we can think of them as contributing to the general stock of ‘assets’ in the country (human capital, physical capital, institutions, and so on), which then generate further value each year at the country’s growth-rate.

Once the benefits spread out even further, we can think of them as contributing to one big pool of world assets, growing at the world growth-rate. We can see that the growth of the benefits produced by the intervention must eventually correspond to the world growth-rate, otherwise they’ll occupy a larger and larger share of the world’s assets (see more detail here).

Note that this ‘world growth-rate’ need not correspond to the economic growth-rate (i.e. GDP growth) and ‘assets’ need not correspond to ‘economic wealth’. What we care about is the growth of whatever is valuable, which may or may not be well-measured by economic wealth and growth.

If we convert all the benefits from the unit of resources into a single unit of ‘social return’, then the value created over time would look something like this:

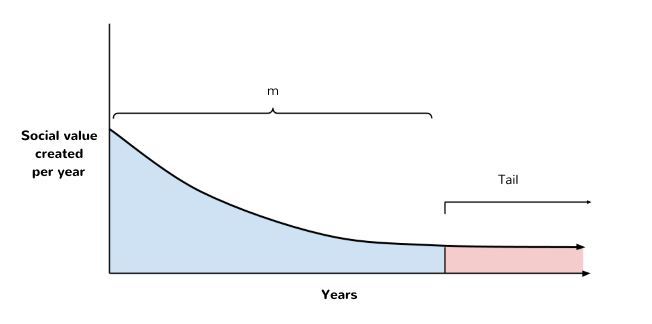

To simplify, we can divide this profile of returns into two chunks: an initial chunk and the tail. In the tail, the annual returns are equal to the world growth-rate, g (note that this growth-rate will change over time, and will eventually approach zero). Once we’ve subtracted the tail, we can model everything else as a one-off multiplier on your initial allocation, m.

Note that m depends on the intervention at hand, e.g. malaria nets or technology R&D. When comparing two interventions, the more effective one will be the one with the bigger m. The aim of cost-benefit analysis is essentially to estimate the m of different interventions.1

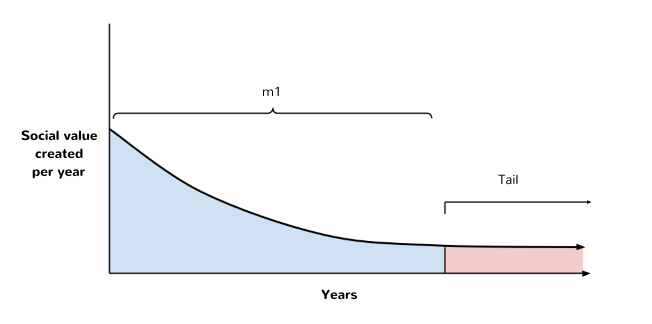

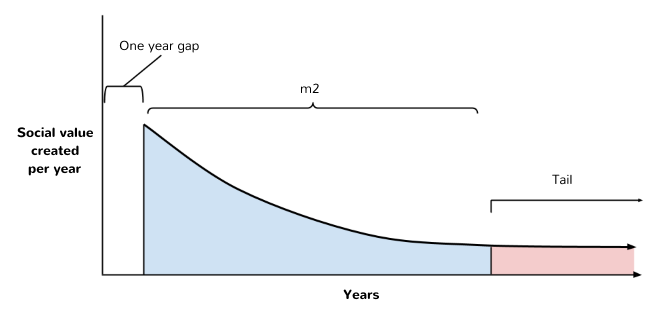

We can now compare two scenarios. One in which you spend the money today, and another in which you wait a year and spend it then. The return profiles look like this:

Spend money today:

Spend money in a year:

In the gap of one year, you invest your resources, earning a return, r. But you lose one year of growth, g, from the start of the tail.

So, the question of which option is better roughly boils down to:

- What’s r – g over the next year at the margin?

- How does m2 compare to m1 at the margin?

How is m changing over time?

We think a good starting point is to assume that m is roughly constant over time. Thinking that it’s unusually high or low amounts to thinking that the present is unusual, and you shouldn’t think that the present is unusual unless you have strong reasons (which people sometimes have, but our first reaction is to be skeptical).

If forced to guess the direction of m, then we’d guess it will increase over the next few years.

There are three main factors at play. First, society may be getting wiser, which means people are getting better at taking the best opportunities. On the other hand, you can also expect to get wiser over the next few years, which means you’ll be able to find opportunities with a higher m. The question then becomes, are you getting wiser faster than the rest of the world or not?

If you’re at the start of your career, you can expect to get much wiser in the coming years, as you learn more about yourself and the world. Think about how different your views are today compared to ten years ago.

You can also expect to benefit from the research produced by groups within the effective altruism, strategic philanthropy and evidence-based policy movements. A serious research program to work out which causes have the most impact is relatively new, so we can expect more discoveries in the next few years.2 For more, see Paul’s essay on this topic.

On the other hand, as more progress gets made, we should expect it to become harder and harder to make more progress (‘diminishing returns’). That’s because the best opportunities get used up. For instance, we can only provide sanitation to a community once.

However, we expect this effect to be small over the next few years compared to increasing wisdom, so overall we expect higher m in the future. This favours giving later.

Note that your views about diminishing returns closely connect with your views about causes. If you’re mainly interested in global health, then returns will diminish quickly, because the best opportunities are rapidly being used up. If instead you mainly care about the long-run future, then returns might even be increasing, because technology is giving us greater power to alter the long-term direction of civilization (for good or ill!).

What is r minus g?

We think r is often higher than g, which also favours giving later.

To estimate g, one starting point is the rate of world economic growth over the next few decades. From 1900 to 2000, it was 1.9% in the West.3 The world economy has never grown faster than about 4% per year, which it did briefly after World War II.4

There’s a complex debate about the extent to which economic growth tracks real value. For instance, economic growth doesn’t fully account for the costs of environmental damage, which would mean it’s overstating true progress. However, this doesn’t matter too much to our equation, because r is often higher than g by a substantial margin – whether we’re discussing financial investments or investments in your own human capital.

The long-run world average return on investing in global stockmarkets is about 5%,5 suggesting it’s generally better to invest your money and donate later. Rates of return on investing in your own human capital can be much higher. For instance, the returns on doing an undergraduate degree due to higher income are likely 10-15%, and it seems likely these expected financial returns reflect a more general increase in your career capital (though there’s a debate about whether this consists of signalling, skill development, or networking). There seem to be other investments in education that can yield even higher returns. For instance, we’ve seen several cases of people almost doubling their income in under a year by learning to program.

More broadly – and we take this to be a common-sense position – we think that people can often increase their career capital very significantly in their first couple of years of work as they gain basic skills and start to accumulate a professional network.

However, your opportunities to invest in your human capital decline over time. This is because you’ll use up the best investment opportunities: you can only learn to read once – a very useful investment in your career capital! It’s also because investments made later in your career yield lower returns, because you’ll have less time to reap the benefits, e.g. if you learn to program at age 64, you’ll only have one year in which you can use the new skill.

What conclusions can we draw from this reasoning?

The model and our views of the key parameters suggest focusing mainly on investing to give later, especially at the start of your career (ignoring the indirect effects that we discuss in the next section). Of course, it’s always possible to stumble across an unusually good opportunity to either invest or give now, so there will be exceptions.

How much weight should we put on these results? We’ve considered more complex ways of modelling the situation, and think the question of which parameters are most important seems fairly robust: how does r compare to g and do you think giving opportunities now are unusually good or bad? The main uncertainty lies in the values you put into the parameters, especially the change in m over time.

Our views about the parameter values could easily change. However, given that the result also agrees with our impression of the common-sense, we think it’s justified to put significant weight on it. The common-sense path for a high-impact career is to invest in building your skills and resources from age 18 to 30-50 (depending on your field), then turn towards giving back when you’re older.

Other indirect effects

There are several effects not captured by the previous model, which overall push back in favour of making a difference now rather than later. We’ll look at these below.

Learning more and signalling

Trying to make a difference now can teach you about what’s most effective and how the world works, which could alter what you do over the rest of your career. This is reason to spend some of your time and money now helping others, even if your main focus is building career capital.

This is especially true because making a difference now shows people that you’re serious about helping others, which could help you find better people to work with and better opportunities to make a difference in the future. For instance, within donating money, GiveWell have found it’s much easier to find further opportunities if they publicly commit to supporting certain causes.

Your motivation and habits

Making a difference now is motivating, keeps you involved with altruistic people and helps you build up altruistic habits, such as living frugally. For this reason, we doubt it’s best to completely forget about making a difference for the next twenty years, to only focus on building skills, connections and wealth. That could easily lead to burning out or giving up on your aims to help the world.

Corruption

You might think there’s some chance you become less concerned with making a difference as you get older, making it better to commit now. However, there are other ways to tie yourself to the mast, such as putting your money in a donor-advised fund, making friends with altruistic people, and making a public declaration to lead a high-impact career.

Your personal capacity

Making a difference requires reflection, and you only have a limited amount of time to reflect. Donating money usually involves saving up, then dedicating lots of time to working out how to spend it later in your life. So with your career, it may be easier and more productive to focus on building skills, then work out which causes to get involved with later.

Taxes

When donating money, there can be tax considerations. For instance, you can normally only claim tax relief on donations against this year’s income, which favours giving now. However, it’s possible to partially get around this problem with a donor-advised fund.

What about groups and coordination effects?

If you’re coordinating with a group, what matters is the distribution between giving now and giving later, over the entire group. You’ll want to do whatever best brings the group’s allocation into line with the optimum.

For instance, the community of people following GiveWell shouldn’t save 100% of their resources to donate later. If they did that, GiveWell would fail. Even if GiveWell weren’t going to fail, it would still be important to spend some resources now so that GiveWell can learn more about what works, enabling them to make better decisions in the future. Let’s suppose the optimal allocation is 80% saved and 20% donated in the next ten years. If you think the current allocation will be 90% saved, then you might want to mostly donate now, even though on average you’re in favour of saving. At the 2014 CEA Weekend Away, Carl Shulman argued that because Good Ventures is only spending a few percent of its assets each year, and Good Ventures represents the vast majority of the resources backing GiveWell, individual small donors supporting GiveWell should consider donating more now.

Our overall views

Based on all the above, if deciding to spend now or invest to give later, you should ask yourself the following questions:

- Is this an unusually good opportunity to make a difference now (compared to what will be available in the future)?

a. Are you getting wiser faster than the rest of the world?

b. Are the best opportunities getting used up faster than new ones are discovered? - By investing, can you earn a return substantially above the world growth-rate (probably a couple of percent per year)?

We think the answer to the first question is usually “no” and the answer the second question is usually “yes” – especially at the start of your career – which favours investing to give later.

However, due to considerations about learning, motivation and corruption, most people should still put some weight on making a difference now even if it’s not their main focus. For instance, if choosing between two options, focus on the one that best builds your career capital, but use immediate impact as a tie-breaker; or if you end up in a job that doesn’t make much difference, give 10% of your income to effective charities.

These views are reflected in how we weight the different elements of our framework at different stages of your career, as explained on our framework page. We start by putting a little weight on path impact potential, and increase it over your career. The pattern for career capital and exploration value is the reverse.

If you’re especially worried about losing your desire to make a difference when you age, or find it very motivating to make a difference immediately, then you could prioritise path impact potential over career capital substantially earlier in your career.

If you’re coordinating with a group, then the analysis needs to be applied to the group as a whole, and your best action depends on what everyone else is doing.

- If you work out the stream of benefits produced over time by the intervention, and then discount at the world growth-rate, you’ll essentially end up with m. ↩

- The Copenhagen Consensus, the Gates Foundation, Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab, GiveWell, The Future of Humanity Institute, and our parent organisation, CEA, were all founded on or after the year 2000. The Cochrane Collaboration (a major driver of the evidence-based movement in medicine) was founded in 1993. Of course, there has been lots of relevant academic inquiry produced for hundreds of years, especially in economics, but there seems to have been an acceleration in recent decades, especially from the perspective of actually applying the results to make real decisions. ↩

- Maddison, Angus; “Contours of the World Economy 1-2030 AD: Essays in Macro-Economic History”, (2007), Oxford University Press ↩

- Expected Returns, by Antti Ilmanen (2011), Wiley Finance

The global economy has never, before or since, grown as fast as the 4% annual real growth pace after World War II. (Slightly over half of this was per-capita growth, the rest population growth which was unsustainable and has not been sustained.)

- According to Expected Returns, the long-run real return of world stockmarkets was 5.4%, with a range of 2.1 to 7.5%. p127 Expected Returns, by Antti Ilmanen (2011), Wiley Finance, which quotes a paper: Credit Suisse Global Investment Returns Yearbook 2010, Dimson, Marsh and Staunton (2010), Credit Suisse. ↩