What skills or experience are most needed within professional effective altruism in 2018? And which problems are most effective to work on? New survey of organisational leaders.

Read this to see the 2019 data.

Update April 2019: We think that our use of the term ‘talent gaps’ in this post (and elsewhere) has caused some confusion. We’ve written a post clarifying what we meant by the term and addressing some misconceptions that our use of it may have caused. Most importantly, we now think it’s much more useful to talk about specific skills and abilities that are important constraints on particular problems rather than talking about ‘talent constraints’ in general terms. This page may be misleading if it’s not read in conjunction with our clarifications.

What are the most pressing needs in the effective altruism community right now? What problems are most effective to work on? Who should earn to give and who should do direct work? We surveyed managers at organisations in the community to find out their views. These results help to inform our recommendations about the highest impact career paths available.

Our key finding is that for the questions that we asked 12 months ago, the results have not changed very much. This gives us more confidence in our survey results from 2017.

We also asked some new questions, including about the monetary value placed on our priority paths, discount rates on talent and how current leaders first discovered and got involved in effective altruism.

Below is a summary of the key figures, some caveats about the data’s limitations, an explanation of the survey method, and a discussion of what these numbers mean.

Note: On Oct 12 this post was edited to make its conclusions clearer.

Table of Contents

- 1 Some key findings

- 2 Want to work at one of the organisations in this survey?

- 3 How the survey was conducted

- 4 Full analysis of the results

- 4.1 What skills and abilities do we need more of?

- 4.2 EA leaders believe that giving focused on the long-term future and the EA community is more effective than that on global development or animal welfare

- 4.3 What’s the key bottleneck for the effective altruism community?

- 4.4 EA leaders are willing to sacrifice a lot of extra donations to hold on to their most recent hires

- 4.5 They think success in priority paths outside their organisations is also quite valuable

- 4.6 They report quite high discount rates on future donations

- 4.7 Half would give up two suitable hires in two year’s time in exchange for their last hire

- 4.8 Current leaders came to be involved through a wide variety of different channels

- 5 Conclusion

- 6 Want to work at one of the organisations in this survey?

- 7 Read next

- 8 Acknowledgements

- 9 Appendix 1 – How the survey was conducted

- 10 Appendix 2 – Answers to open comment questions

- 11 Appendix 3 – Additional answers from animal and poverty focused organisations

Some key findings

- EA organisation leaders said experience with operations or management, and generalist researchers are what their organisations will need most of over the next five years.

- They said the community as a whole will most need more government and policy experts, operations experience, machine learning/AI technical expertise, and skilled managers.

- Most EA organisations continue to feel more ‘talent constrained’ than funding constrained, rating themselves as 2.8/4 talent constrained and 1.5/4 funding constrained.

Leaders thought the key bottleneck for the community is to get More dedicated people (e.g. work at EA orgs, research in AI safety/biosecurity/economics, etg over $1m) converted from moderate engagement. The second biggest is to increase impact of existing dedicated people through e.g. better research, coordination, decision-making.

We asked leaders their views on the relative cost-effectiveness of donations to four funds operated by the community. The median view was that the Long-Term Future fund was 1.6x as cost-effective as the EA Community fund, which in turn was 10 times more cost-effective than the Animal Welfare fund, and twenty times as cost-effective as the Global Health and Development fund. Individual views on this question varied very widely, though 18/28 respondents thought the Long-Term Future fund was the most effective.

In addition, we asked several community members working directly on animal welfare and global development for their views on the relative cost-effectiveness of donations to these funds. About half these staff thought the fund in their own cause area was best, and about half thought either the EA Community fund or Long-Term Future fund was best. The median respondent in that group thought that the Animal Welfare fund was about 33% more cost-effective than the Long-Term Future fund and the EA Community fund – which were rated equally cost-effective – while the Global Development fund was 33% as cost effective as either of those two. However, there was also a wide range of views among this group.

The organisations surveyed were usually willing to forego several hundred thousand dollars in additional donations to make the right person available for a junior position in their organisation 3 years earlier, and over a million for the right person for a senior role. One reason for the high figures is that these positions usually require a rare combination skills, and so despite their value, people shouldn’t necessary aim to fill them.

Want to work at one of the organisations in this survey?

Speak to us one-on-one. We know the leaders of all of these organisations and current job openings, so can help you find a role that’s a good fit.

You can also read more about these kinds of jobs.

Or find top vacancies at many of these organisations on our job board.

How the survey was conducted

The methodology is described in more detail in Appendix 1. The weaknesses of the method are discussed below. We’ve tidied up and anonymised the free text responses to various questions and put them in Appendix 2.

Who was sampled

As last time, our goal was to include at least one person from every organisation founded by people who strongly identify as part of the effective altruism community that has full-time staff, and we got most of the way there. We also included some community leaders who currently work at other organisations.

Our total sample was 37 people though not everyone answered every question. The survey includes (number of respondents in parentheses): 80,000 Hours (3), AI Impacts (1), Animal Charity Evaluators (2), Center for Applied Rationality (2), Centre for Effective Altruism (2), Centre for the Study of Existential Risk (1), Berkeley Center for Human-Compatible AI (1), Charity Science: Health (1), DeepMind (1), Foundational Research Institute (2), Future of Humanity Institute (2), GiveWell (1), Global Priorities Institute (2), LessWrong (1), Machine Intelligence Research Institute (1), Open Philanthropy (4), OpenAI (1), Rethink Charity (2), Sentience Institute (1), SparkWave (1), and Other (5). The survey mostly took place at the EA Leader’s Forum in Oakland in June 2018. We also emailed the survey to last year’s participants to fill in some gaps. The response rate was around two-thirds.

The reader should keep in mind this sample does not include some direct work organisations that some in the community donate to, such as the Against Malaria Foundation, or Mercy for Animals. For our additional survey of people working on poverty and animal welfare, we surveyed 13 people at: The Humane League (3), GiveWell (2), ProVeg (2), Compassion in World Farming (2), IDinsight (1) , Charity Science Health (1), Fortify Health (1), Good Food Institute (1).

Weaknesses

- The survey is representative of leaders at the organisations listed – not the effective altruism community more broadly. This could be viewed as a strength or a weakness depending on what you want to know, but regardless – it needs to be kept in mind.

- Many people will have answered these difficult questions quite quickly without doing serious analysis. As a result the results will often represent a gut reaction rather than deeply considered views. In other cases, these answers reflect large amounts of thought over many years. We should update our views on these answers, but sometimes those updates will be small. Certainly the answers here are not the final word on the relevant questions.

- The survey included 37 people from a range of organisations, but they did not all answer every question (see the presentation for sample sizes on each question). The average number of answers across all questions was 25 and the question with the fewest responses had 18 answers.

- Last year we tried weighting answers by the budget of the organisation the respondent came from (splitting the weight where an organisation had multiple people fill out the survey). This made little difference to the answers and was by far the most time-consuming piece of the analysis, so we’ve skipped it this time. That said, the number of participants included from various organisations is somewhat arbitrary.

- We tested the questions in an attempt to make them clear and unambiguous but we know some were open to multiple interpretations or misunderstandings. For example, some people only considered the benefits of an expanded hiring pool to their own organisation, rather than the world as a whole as we intended.

Full analysis of the results

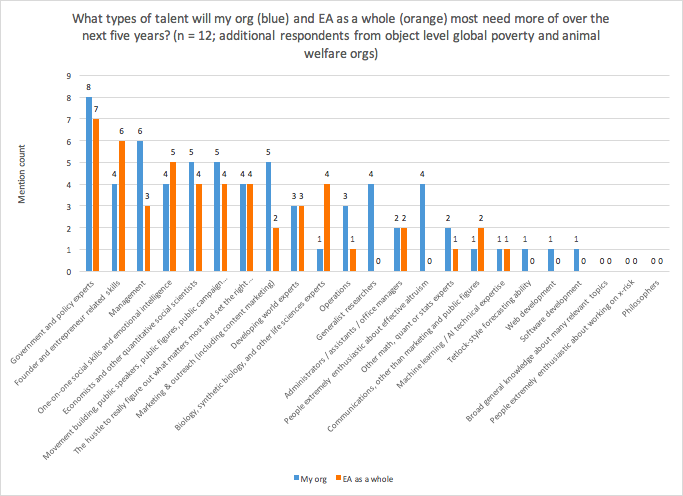

What skills and abilities do we need more of?

We asked two questions on this topic:

- What types of talent will your organisation need more of over the next 5 years? (Pick up to 6)

- What types of talent will we need more of in EA as a whole over the next 5 years? (Pick up to 6)

| Skill | My org | EA as a whole | Sum |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operations | 20 | 21 | 41 |

| Management | 20 | 17 | 37 |

| Generalist researchers | 19 | 14 | 33 |

| Government and policy experts | 7 | 23 | 30 |

| Machine learning / AI technical expertise | 11 | 19 | 30 |

| The hustle to really figure out what matters most and set the right priorities | 10 | 15 | 25 |

| Founder and entrepreneur related skills | 9 | 14 | 23 |

| One-on-one social skills and emotional intelligence | 8 | 9 | 17 |

| Administrators / assistants / office managers | 8 | 6 | 14 |

| Economists and other quantitative social scientists | 6 | 8 | 14 |

| Movement building, public speakers, public figures, public campaign leaders | 5 | 8 | 13 |

| Tetlock-style forecasting ability | 6 | 6 | 12 |

| Other math, quant or stats experts | 8 | 3 | 11 |

| Broad general knowledge about many relevant topics | 6 | 3 | 9 |

| Marketing & outreach (including content marketing) | 7 | 1 | 8 |

| People extremely enthusiastic about working on x-risk | 7 | 0 | 7 |

| Biology, synthetic biology, and other life sciences experts | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| Web development | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| Software development | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| Communications, other than marketing and public figures | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| People extremely enthusiastic about effective altruism | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Developing world experts | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Philosophers | 2 | 0 | 2 |

Operations, management, and generalist researchers are the types of talent respondents most frequently said their organisations will need more of over the next five years. This was a change from last year when management was a distant second to generalist researchers and operations was near the middle of the pack.

Relatively few respondents said increasing government and policy experts was a priority at their organisations but for the second year in a row it was the need most frequently mentioned for EA as a whole. It’s not clear whether respondents believed the need is for community members with this expertise to: 1) work in government; 2) work on policy issues at organisations outside of the community; or 3) found new organisations focused on policy.

In order, the next few most commonly listed needs for EA as a whole were more: operations, machine learning/AI technical expertise, and management talent. The most notable changes from last year were an increase in the perceived need for operations talent and a decrease in the perceived need for additional talent in movement building/public speaker/public figures/public campaign leaders.

The high demand for operations talent – both at the organisations surveyed and the community at large – is consistent with our article, Why operations management is one of the biggest bottlenecks in effective altruism.

We’ve also produced two podcasts on this topic:

- Tara Mac Aulay on the audacity to fix the world without asking permission

- Tanya Singh on ending the operations management bottleneck in effective altruism

Also in substantial demand were generalist skills like ‘the hustle to set the right priorities’, entrepreneurship, and emotional intelligence.

These results are quite close to those from last year.

Which skills were less mentioned?

- Web development

- Software development

- Communications, other than marketing and public figures

- People extremely enthusiastic about effective altruism

- Developing world experts.

We suspect that in most cases what’s driving the low scores is the preponderance of people in the community who already have these skills.

For a second year running the glut of philosophy graduates in the community leaves philosophers at the bottom of the list.

However, the situation could easily change. In 2016, there was significant demand for web developers and engineers. We expect the community will continue to grow on the whole so there will be an increased need for people with many talents even those that weren’t among the most cited. If you have sufficiently high personal fit in one of these skill-sets, it can still be a great option.

Most interesting among a group of people working to promote the ideas associated with effective altruism, is that few believe a key limiting factor over the next few years will be people enthusiastic about effective altruism. Rather it’s specific skills that are in short supply.

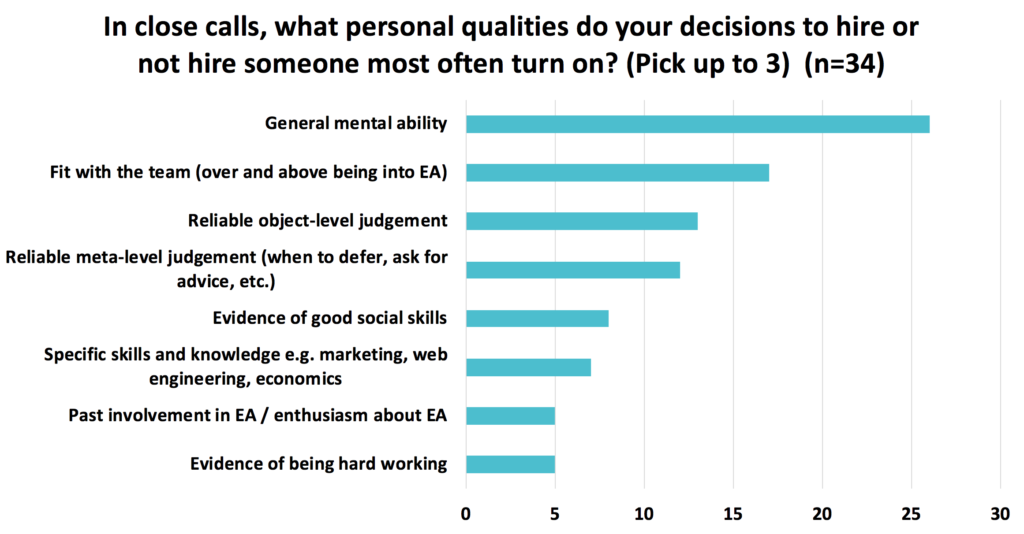

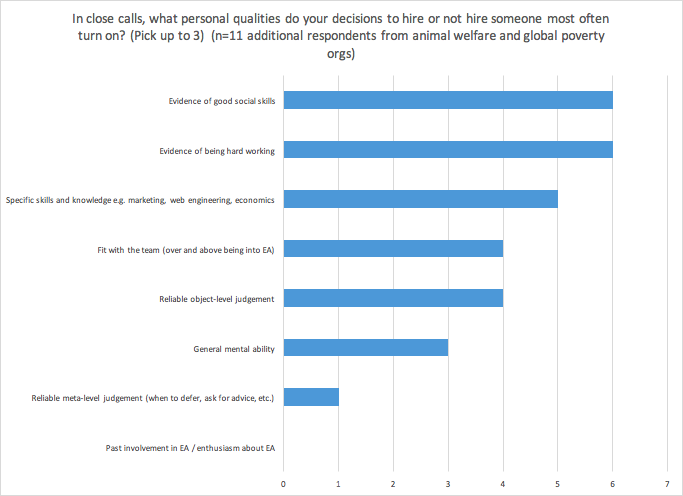

When choosing who to hire, decisions would most often turn on general mental ability, fit with the team (other than sharing EA values) and good judgement:

Surprisingly there was less interest in specific skills, involvement with EA or conscientiousness.

EA leaders believe that giving focused on the long-term future and the EA community is more effective than that on global development or animal welfare

We asked leaders the following:

Imagine a donation of $1,000 to the EA Community Fund. In your view, this is equally as valuable for the world as a pure donation of $X to the Global Health EA Fund. Or a donation of $Y to the Long-Term Future EA Fund. Or a donation of $Z to the Animal Welfare EA Fund.

We then converted this into relative cost-effectiveness. The median response regarding the cost-effectiveness of the different EA funds was the following:

| (n=27) | Cost-Effectiveness of each fund relative to the EA Community fund according to community leaders (higher is better) | ||

| 10th percentile | Median | 90th percentile | |

| EA Comm Fund | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Long-Term Future Fund | 16 | 167 | 283 |

| Animal Welfare Fund | 3 | 10 | 107 |

| Global Development Fund | 1 | 5 | 63 |

We can look at the results another way, by seeing how many people thought each fund was the most and least cost-effective of the four (votes are split in case of a tie):

| (n=27) | Votes for this fund being most cost-effective | |

| Fund | 2017 | 2018 |

| Long-term future fund | 11.75 | 18 |

| EA community fund | 6.75 | 7 |

| Animal welfare fund | 1.75 | 2 |

| Global development fund | 2.75 | 1 |

Again, it’s clear that the group had quite a strong preference for work to improve the long term future and quite a strong preference against the global development fund – a preference that has slightly strengthened in the last year.

We also asked respondents whether this question was a good proxy indicator for the relative value they expected to be generated by people going to work on those 4 different ways of doing good. Three quarters gave a 3 or 4 on a scale from 0-4, suggesting it was decent for most.

These answers contrast with a 2017 survey of 1,450 community members, defined as people who said ‘they could, however loosely, be described as an effective altruist.’ In that survey 41% of respondents gave poverty reduction as their ‘top priority’.

This suggests a significant difference of opinion between leaders at the organisations surveyed and the broader community.

What might be the cause of this? One possibility is that our survey shows that the intellectual leaders of the community are fairly united in wanting to focus on the long-term future. The broader survey, however, includes many people who report agreeing with effective altruism’s core ideas but have not had the opportunity to (or chosen to) engage with effective altruism full-time. They may not have had equal exposure to the arguments that convinced these leaders of long-termism, and may prioritise global poverty just because the base rate of support for global poverty is very high, and almost no one outside of the EA/rationality communities starts out focused on the importance of future generations. Moreover, effective altruism’s past press coverage and outreach focused on global poverty, which may mean effective altruism has specifically selected for people already dedicated to this problem.

A second possibility is that effective altruism leaders have been convinced of long-termism for bad reasons. We can think of several reasons this might be. Perhaps people who are working in an area full-time, or see themselves as intellectual leaders, have an incentive to believe arguments that make the movement seem counterintuitive, controversial or cutting edge. They may prefer causes favored by compelling abstract arguments over those that are more solvable. They may be easily captured by intellectual fashion or they may be ‘countersignaling’ by deprioritising forms of altruism with mainstream acceptance. There might also be selection bias in who becomes a leader of an effective altruist organisation – existing leadership might be wrongly biased toward hiring people who agree with them or share their idiosyncratic ideas.

Another possibility is the result mainly arises from a biased sample: the organisers of the forum could have been more likely to invite community leaders who are focused on the long-term future. We tried to test this hypothesis in several ways.

First, we tried to categorise what respondents themselves were working on and got long-term future (10), meta-research (8), movement building (7), animal welfare (4), poverty (2) and other (5). So it is true that there were many more attendees themselves working on long-termist issues than poverty. However, this could easily be explained by EA Leaders choosing to work in areas consistent with their priorities. If effective altruism’s leadership became convinced today that Cause Y was the top priority, we’d expect that many of them would be working on that cause in a few years’ time.

Next, we looked into our criteria for including people into the survey. We tried to include at least one person from every organisation founded by people who strongly identify as part of the effective altruism community that has full-time staff, and we got most of the way there. This doesn’t seem biased to us but it does exclude many global poverty and animal welfare organisations that members of the community donate to, including all of GiveWell and Animal Charity Evaluators’ recommended organisations.

We did include more people from organisations focused on long-termism. It’s not clear what the right method is here, as organisations that are bigger and/or have more influence over the community ought to have more representation, but we think there’s room for disagreement with this decision.

To check whether our decision about how many people to include from each organisation was driving the results, we repeated our analysis, giving each organisation a single vote, split between respondents from each organisation. This did not substantially change any of our conclusions.

What do people working directly on global poverty or animal welfare think?

As another approach to identifying potential bias, we reached out to 20 people who were working at GiveWell, or organisations recommended by either GiveWell or Animal Charity Evaluators at some point, who primarily identified as ‘effective altruists’ before taking their current job.

We’d expect that those in the community who do favor animal welfare and global poverty are more likely to go work in those areas. So if staff at these organisations prefer their own areas, it will just reaffirm that there is disagreement, and that the results of the survey are sensitive to debatable decisions about who to include.

On the other hand, if even staff at those organisations concede that work focused on long-term future issues is equally or more impactful, then it would provide evidence in favour of general agreement among staff in the movement as a whole.

We received 13 responses. Two said they did not know enough about work on the long-term future to have an opinion on the effectiveness of that fund so we were left with 11 respondents who ranked all 4 funds – 6 working on animal welfare and 5 working on global poverty.

The median respondent thought that the EA Community fund and the Long-Term Future fund were roughly equally cost-effective. They thought the Animal Welfare fund was 33% more cost-effective than the EA Community fund, and that the Global Health and Development fund was 66% less cost effective than the EA Community fund.

| Cost-Effectiveness of each fund relative to the EA Community fund according to EAs working on global health or animal welfare (higher is better) | |||

| Minimum | Median | Maximum | |

| EA Community fund | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Long-Term Future fund (n=11) | 10 | 100 | 1000 |

| Animal Welfare fund (n=13) | 10 | 133 | 1000 |

| Global Health and Development fund (n=13) | 1 | 33 | 500 |

Among this group, 26% thought the EA Community Fund was most effective, 21% thought that of the Long-Term Future Fund, 35% thought that of the Animal Welfare Fund, and 18% thought that of the Global Health and Development Fund.1

These data should be interpreted with caution. The sample was fairly small and there was a wide range of views. However, overall it looks like:

- It was most common for people in this sample to believe funding their own field was most effective;

- But it was nearly as common for people in this group to think funding for the Long-Term Future or EA Community Building was equally effective or more effective than work on their own causes;

- On the other hand, the reverse was not true – nobody in the previous sample working on EA Movement Building or the Long-Term Future thought work directly on global poverty or animal welfare was equally as cost-effective.

As a final test, we added these eleven additional respondents working at animal welfare and global poverty organisations to our initial sample of 27 EA leaders. This bring the sample closer to the actual distribution of people in the community doing direct work on these four problems.

In this expanded sample, the Long-Term Future fund and EA Community fund were still favored quite strongly, although the consensus was somewhat weaker than in our original sample.

| (n=39) | Cost-Effectiveness of each fund relative to the EA Community fund (combined response from both surveys) | ||

| 10th percentile | Median | 90th percentile | |

| EA Community fund | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Long-Term Future fund | 17 | 100 | 275 |

| Animal Welfare fund | 4 | 23 | 230 |

| Global Health and Development fund | 1 | 10 | 98 |

The fact that our overall conclusions seem to hold up even after adding additional staffers at animal welfare and global health and development organisations to the sample is some evidence for the robustness of the finding that EA leaders strongly favor work on the long-term future and EA community building over global development and animal welfare. Of course, as argued above, the fact that EA leaders hold this view does not necessarily mean that they are right.

Tables with additional data from this supplemental survey can be found in Appendix 3.

What’s the key bottleneck for the effective altruism community?

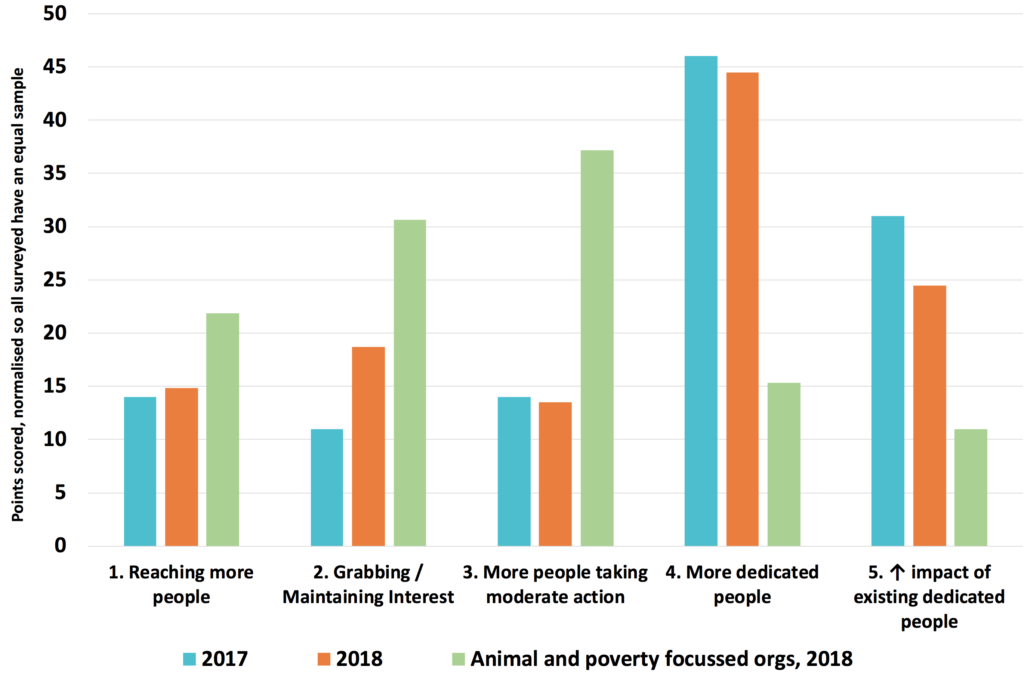

We also asked attendees what they believed were the top 3 key factors limiting the community’s ability to do more good. We broke stages of involvement down into five parts, which follow sequentially, and asked where people thought the key bottleneck lay.

First place got 3 points, second place 2 points, and third place 1 point. The results are in the table below.

Note that each stage is a “conversion rate” from the previous stage. So if you answer stage (3), “more people taking moderate action”, it means that the key bottleneck is taking people from (2) to (3).

These results are almost identical to last year.

Attendees continue to believe that the main bottleneck in the pipeline isn’t reaching new people, but rather i) advancing people involved to the point where they’re dedicated to working on high priorities full-time, ii) and then helping those people accomplish more, with e.g. better training and access to information.

Because we agree with this view, 80,000 Hours has reoriented its material over the last year from the first 3 stages – which we previously felt might be the bottleneck – towards the last two.

We also put in the views from 9 people working at animal and poverty focused organisations – and scaled them up to have the same number of votes – which shows they are focused earlier in the pipeline, getting interest and encouraging people to take their first steps (perhaps becoming vegetarian, or donating).

Learn more about our views on how the effective altruism community can coordinate to do more good together:

- Doing good together — how to coordinate effectively, and avoid single-player thinking

- Should you play to your comparative advantage when choosing your career?

- Considering Considerateness: Why communities of do-gooders should be exceptionally considerate

EA leaders are willing to sacrifice a lot of extra donations to hold on to their most recent hires

Update May 2019: We’ve written up a more detailed exploration of these results, and why we do not think the precise numbers are a reliable answer to decision-relevant questions for job seekers, funders, or potential employers.

We asked organisations how much they’d be willing to give up in future donations in order to retain their most recent hires. Unfortunately, we do not have very much confidence in the answers to these questions and the particular way we worded them limits their relevance to most career decisions. We would not recommend updating very much based on them.

Nevertheless, we report the results, as well as some of our concerns, below.

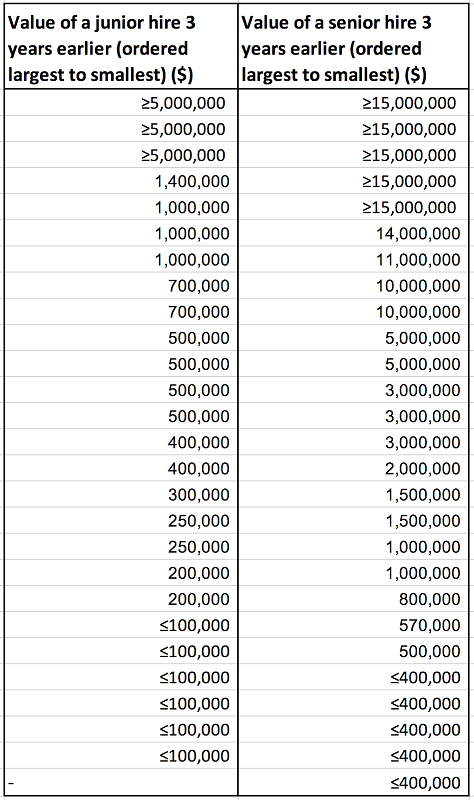

Out of 27 people who answered, 9 said they’d be willing to forgo $10 million or higher in additional donations to prevent a recent senior hire from leaving for three years. For junior hires, the median was $450,000, with 7 willing to forego $1 million or more.

Here is the exact question we asked:

For a typical recent Senior/Junior hire, how much financial compensation would you need to receive today, to make you indifferent about that person having to stop working for you or anyone for the next 3 years?

| Senior hire | 2017 (n=24) | 2018 (n=27) |

|---|---|---|

| Average | $8,200,000 | $7,400,000.00 |

| 10th Percentile | $500,000 | $380,000.00 |

| Median | $1,000,000 | $3,000,000.00 |

| 90th Percentile | $19,000,000 | $20,000,000.00 |

| Junior hire | 2017 (n=23) | 2018 (n=26) |

|---|---|---|

| Average | $1,300,000 | $1,050,000 |

| 10th Percentile | $30,000 | $60,000 |

| Median | $250,000 | $450,000 |

| 90th Percentile | $1,000,000 | $3,210,000 |

Here are the full results, which show a great deal of spread:

Typical senior roles were Director of Operations, Director of Research and CEO/Founder. Typical junior roles were a Research Assistant, Events Organiser, Administrator and Web Developer.

The answers are very similar to those in 2017.

Note that the question refers to the value of retaining a past hire, not the value of setting out to find the next hire, which could be quite a bit lower.

Given these high figures – much higher than typical salaries – why aren’t these organisations hiring people very quickly? We try to explain that seeming puzzle here. In the process we show that these results may not imply very much for people who don’t have a comparative advantage in working at these organisations.

The answer to this trade-off is most relevant for someone who has a job offer at one of these organisations, and is deciding between working there, or earning to give for them. Because the survey asks about existing staff, it’s even more applicable to people who are already working there.

We have additional concerns about these results.

First, we didn’t get respondents to consider the opportunity cost of their employees’ time, or donors’ money. As a result these numbers are inflated relative to what funders should actually be willing to pay to enable an organisation to hire someone. On the other hand, these figures probably don’t take account of the inconvenience caused to other groups if this staff member leaves, and has to be replaced by someone who otherwise would work elsewhere.

Second, it’s hard for even an organisational leader to know how much they should be willing to pay, respondents didn’t take very long in filling out the survey, and they may have been primed by reading the results of last year’s survey.

Also note that these are the amounts of additional donations organisations would be willing to forego in order to keep a recent hire. They would have given different answers if asked how much they’d be willing to pay out of their existing budgets. We discussed more weaknesses of the survey above.

On the other hand, it’s hard to know how to get better data on this question. Respondents consistently gave high answers, and figures like this have been widely discussed and largely accepted since we published similar results last year.

We can also tackle the funding vs. talent question with some other questions.

On a scale of 0 to 4, respondents saw themselves as 2.8 constrained by talent and 1.5 by funding, similar to last year and consistent with the donation trade-off figures.

| (n=34 to 36) | Funding (0-4) | Talent (0-4) | ||

| 2017 | 2018 | 2017 | 2018 | |

| Average | 1.1 | 1.5 | 2.6 | 2.8 |

| 10th Percentile | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.4 |

| Median | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| 90th Percentile | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

(Interestingly, many of the organisations report being neither heavily constrained by funding or talent, suggesting they either feel they are already at their optimal size or are instead constrained by something else, which might be “insights” or “management capacity”).

Supposing the trade-off figures are correct, what does this mean for the value of direct work at these organisations?

If you think these organisations are among the best donation opportunities, then these figures reflect the value of new hires measured in donations to top charities above what they already receive. This suggests that unless the staff who took these roles had outstanding earning ability, they are probably having much more impact through direct work than they would have through earning to give. Though if there’s another organization they could donate to that is more funding constrained and therefore more cost-effective, then that could be better still.

What would be some evidence that you’re in such a position to do particularly valuable direct work?

- You have excellent personal fit for the role – if the organisation would otherwise be able to hire someone only marginally worse than you, the organisation won’t be willing to pay much extra.

- You have an offer to work at one of the more talent constrained organisations, which tend to be the larger ones.

- You have an offer to fill a relatively senior role – the figures are several times higher for senior roles on average.

- You won’t require much effort to train. New hires are less valuable to the organisation than their most recent hire, since recent hires have already been vetted and trained to some degree. This means the figures are an overestimate of the value of marginal hires, unless you’re in a position to “hit the ground running” at the organisation.

- You aren’t in a position to earn very large amounts.

These positions aren’t for everyone – indeed they’re not for most people. The attitude, skills and experience these groups are looking for are not common, which is exactly why they place a lot of value on someone when they do find the right person.

Still, if you’re unsure about your own situation, then these results suggest there’s huge value in finding out whether you might be a good fit. If you are, then it’s likely your highest-impact option.

As a first step to learn more, read our profile about these jobs.

Those who aren’t suited to any of these positions can come up with alternatives using our six-step process for generating promising career paths.

They think success in priority paths outside their organisations is also quite valuable

We also wanted to know how much financial value people would attach to some of our other top priority career paths, especially where the relevant organisations weren’t able to answer themselves.

We asked:

How much should Open Philanthropy be willing to pay today to immediately add someone to the community who is:

- Able to get a job on a strategy research team at OpenAI, DeepMind and/or FHI.

- Able to get an AI-related job as a senior security staffer in the US government.

- Able to get a job doing AI technical safety research at OpenAI, DeepMind and/or MIRI.

- Able to get a policy research role at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security, focused on preventing global catastrophic biological risks.

- Highly capable in general, worried about catastrophic risks, speaks Chinese well though not natively, has lived in China for 2 years, and is about to start a Masters in Public Policy on a prestigious scholarship in China.

The results are shown below:

| (n=18) | Mean | 10th percentile | Median | 90th percentile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI strategy research | $3,950,000 | $190,000 | $1,430,000 | $10,000,000 |

| $11,830,000 | $450,000 | $2,500,000 | $21,500,000 | |

| AI technical safety research | $3,290,000 | $350,000 | $2,500,000 | $8,200,000 |

| Center for Health Security | $1,600,000 | $250,000 | $950,000 | $3,800,000 |

| China specialist | $2,130,000 | $70,000 | $1,000,000 | $5,900,000 |

Note that this question brings someone into the community who otherwise wouldn’t exist – rather than just three years earlier in the previous question – so we would expect these figures to be higher. Though if we take the high discount rates on the arrival of staff that people reported – discussed below – the difference between 3 years earlier and 50 years earlier may not be as big as you’d expect.

These results are difficult to interpret because they depend heavily on respondents’ empirical and normative beliefs about Open Philanthropy’s counterfactual use of funds, as well as their interpretation of the question. For example, some respondents may have believed this spending would displace an equal amount of spending this year on Open Phil’s EA and long-termist program areas. Others may have assumed it would displace Open Phil’s “last dollar,” which might be global health spending thirty years from now.

Keeping those major caveats in mind, while there was a wide range of views, the results suggest that respondents believed recruiting people to fill these roles would be worth large amounts of funding from an aligned donor.

You can find out whether you’re a good fit for these positions above by reading our profiles on them here:

- AI strategy research

- AI policy implementation

- US AI policy expert

- AI technical safety research

- Catastrophic biological risk researcher

- China specialist

They report quite high discount rates on future donations

We asked leaders what donation in three years’ time would be of equal value to a donation of $100,000 today, and from that inferred an annual discount rate. We report the results below but we have very low confidence in them and strongly recommend against making major changes to your plans based on them.

While the median discount rate for donations was 16%, 12 out of 26 respondents gave a discount rate on future donations above 20%, and 6 above 50%. These latter groups believe they benefit significantly more from a donation now than the same donation guaranteed to arrive in a year’s time.

| 2017 (n=17) | 2018 (n=25) | |

| Average | 15% | 28% |

| 10th Percentile | 4% | 8% |

| Median | 14% | 16% |

| 90th Percentile | 26% | 65% |

We have serious concerns about these results and believe they should be interpreted with particular caution.. For instance, there are many complications beyond the scope of this post that could cause these organisations to have much higher discount rates than would make sense for the community as a whole. As one example, an organisation could have an extremely high discount rate if it was close to folding due to lack of funds but this should only affect the community’s discount rate if keeping the organisation afloat is among the very best uses of money.

Overall, we would not recommend anybody make major changes to their plans based on these findings.

Half would give up two suitable hires in two year’s time in exchange for their last hire

We also asked a new question about how urgently organisations needed suitable staff to appear:

Imagine your last good hire, or a good hire at an org you’re familiar with. For what value of X would you be indifferent between that person appearing when they did, or two people of the same ability appearing in the community (and starting to work for your org if you like) X years later?

This is another case where we have serious concerns about our results and caution strongly against using them to make substantial changes to your career.

The question is somewhat confusing – a discount rate on new hires is a bit challenging to elicit, because people are not uniform and divisible in the way money is. A few respondents mentioned to us that they placed little value on the second person because their organisation didn’t need two people with the same skills, which wasn’t the intended spirit of the question. Other respondents may have thought this way, too. So as with all of these results, we should take these answers with a pinch of salt.

Nonetheless, the implied discount rates from answers to this question were astonishingly high, with a median of 41%, which would make 2 people who arrive in two year’s time equivalent to one today.

| (n=24) | Years | Implied discount rate |

| 10th Percentile | 6.0 | 12% |

| Median | 2.0 | 41% |

| 90th Percentile | 0.7 | 169% |

Three respondents gave an answer of just ‘six months’ – a mind-boggling 300% annual discount rate. Possible justifications for these figures could be i) that a project is going to fail if they can’t hire a suitable person right away, ii) they view the problem they are working to solve as incredibly urgent, such that any delays are damaging or risky, iii) additional staff today create additional management capacity or recruit further talented community members tomorrow, creating a positive feedback loop and a high rate of return on work performed today, iv) respondents believe the community faces rapidly diminishing returns on certain types of talent, v) respondents misinterpreted the question and assumed the additional person added to the community must also work at their organisation.

Overall, we wouldn’t place much weight on these specific figures. Estimating this kind of discount rate is very complicated and we aren’t confident people thought this through carefully in the limited time they had to answer the survey.

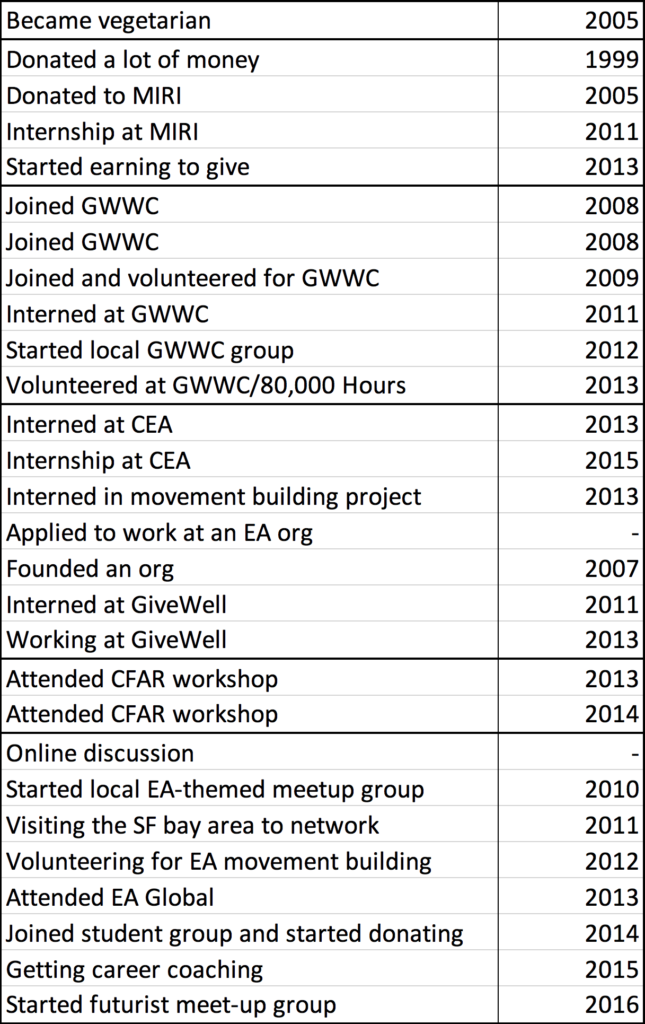

Current leaders came to be involved through a wide variety of different channels

We asked leaders:

How did you first get involved in effective altruism intellectually/online/by agreeing with the ideas? How did you find out about EA? What year did this happen?

Many people encountered multiple sources simultaneously, or couldn’t remember which ones came first, so we just counted the number of mentions of each.

The biggest early points of contact for leaders in the community were Peter Singer (8), LessWrong (6), and Will MacAskill (5). Other utilitarian-leaning philosophers were substantial (9), as was finding out about or attending an event run by Giving What We Can (5).

We were somewhat surprised at the dominance of philosophers on this list. Four people said they independently came up with the drowning child in the pond argument for giving to charity, or decided to earn to give for the most effective charities.

| (n = 29) | Via meeting in person | Via writing | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Independently figured out some ideas (especially earning to give) | 4 | 4 | |

| LessWrong | 6 | 6 | |

| MIRI | 1 | 1 | |

| Steph Zolayvar and Nate Soares | 1 | 1 | |

| Harry Potter and the Methods of Rationality | 1 | 1 | |

| Giving What We Can | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| GiveWell | 2 | 2 | |

| 80,000 Hours | 2 | 2 | |

| Peter Singer | 1 | 7 | 8 |

| Will MacAskill | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Toby Ord | 3 | 3 | |

| Derek Parfit | 1 | 1 | |

| Jeremy Bentham | 1 | 1 | |

| Peter Unger | 1 | 1 | |

| Nick Bostrom | 1 | 1 | |

| Brian Tomasik | 1 | 1 | |

| Reading utilitarian philosophy | 3 | 3 | |

| Felicifia | 2 | 2 | |

| Overcoming Bias blog | 1 | 1 | |

| Other friend | 1 | 1 | |

| Other | 1 | 1 |

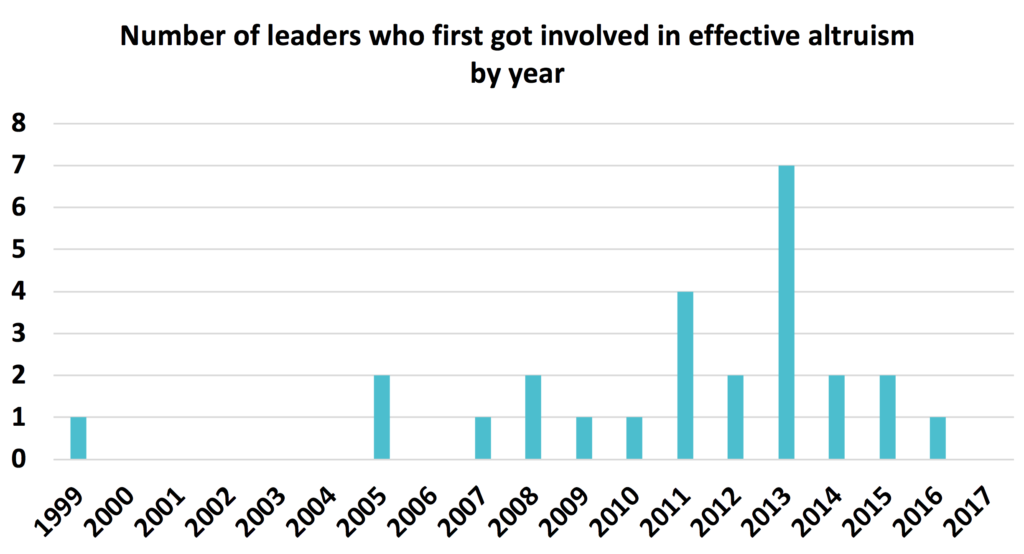

When did people “first get involved in effective altruism in-person/career-wise/taking real action”? The majority did so between 2008 and 2014:

This isn’t surprising because it usually takes several years from first getting involved to building up the track record to join an organisation’s leadership.

You can see what their first meaningful contributions to the community were in Appendix 2.

Conclusion

The effective altruism community’s greatest talent needs are in the fields of operations, management, generalist research, government and policy expertise, and AI/machine learning expertise. The result has stayed fairly constant over the last year, suggesting that these needs are stable and acquiring career capital in these areas could be valuable in the long-run.

People with these skills could do a lot of good through ‘direct work’, and should consider it if they haven’t already.

For those who don’t ever expect to work in the organisations surveyed these results are much less decision-relevant – with the exception of the questions of which of the Effective Altruism funds are most cost-effective.

On that question respondents had a strong consensus on the importance of work focused on the long-term future and building the community. This result was fairly robust to surveying additional staffers working at the latter two fields, but is in tension with the most commonly held views among the community at large.

Respondents again emphasized the importance of increasing the number and effectiveness of people dedicating their careers to doing good most effectively. They saw this bottleneck as more pressing than reaching more people, holding their attention, or having more people take moderate action.

Overall, the survey’s results seem consistent with our view that people can add a lot of value by taking steps to enter one of our priority paths as soon as they are able, or otherwise trying to get into one of our top 5 career categories.

Some of the questions in this year’s survey weren’t as informative as we initially hoped they would be. For next year’s survey we expect to either ask entirely new questions, or interview a smaller number of people in substantial depth, so that we can discuss their answers with them until they reach a reflectively stable view, and we understand what they really mean.

Want to work at one of the organisations in this survey?

Speak to us one-on-one. We know the leaders of all of these organisations and current job openings, so can help you find a role that’s a good fit.

You can also read more about these kinds of jobs.

Or find top vacancies at many of these organisations on our job board.

Read next

- These are the world’s highest impact career paths according to our research

- Doing good together — how to coordinate effectively, and avoid single-player thinking

- Should you play to your comparative advantage when choosing your career?

- Considering Considerateness: Why communities of do-gooders should be exceptionally considerate

- Why despite global progress, humanity is probably facing its most dangerous time ever

Acknowledgements

Thanks to everyone who filled out the survey, and to Ben Todd, Carl Shulman and Owen Cotton-Barratt for looking over it ahead of time.

Appendix 1 – How the survey was conducted

You can see exactly how the survey was taken on Google Forms here.

37 people filled out the survey, though not all respondents answered every question. 18 people who were asked to take the survey did not fill it out, yielding a response rate around two-thirds. Most people responded in June 2018.

Most people who filled it out requested that their answers be anonymised before being shared with anyone else. Unfortunately, for privacy reasons, we can’t share individual survey responses.

The tables and figures are summarised in this brief presentation.

Appendix 2 – Answers to open comment questions

How did you first get involved in effective altruism in-person/career-wise/taking real action? When did this happen?

(Totally optional) Any other comments on what we need more of in the community, or what characteristics or lack thereof most often hold people back from usefully contributing?

- Need more gender and especially ethnic diversity.

- More mid career people with domain expertise in some relevant area + experience at well run organizations.

- Senior figures to mentor junior people.

- People who have an infrastructure building mindset.

- Places for relatively independent researchers to semi-privately get feedback from one another.

- Meta-level judgment.

(Optional) What other hypothetical EA Fund do you think would be similarly effective, or more effective, than the ones above? What would it be focused on? In your view, a donation of $A to this fund would be equally as valuable as a $1,000 donation to the EA Community Fund.

- Breakthrough science fund, $3,000

- Long-term future suffering prevention focus

- Prioritization research/shallow investigations of new areas, $1,000

- More activist versions of the others could be improvements.

- Improving Science and Knowledge Aggregation

- Global pro democracy/liberalism/progress/etc. fund

- Long-Term Future EA Fund that funds slightly more research on things that also reduce s-risks, $100

- A fund reducing the risk of great power war would be more effective (if it had a good fund manager), $400

- A fund on improving politics (in a long termisty way) would be pretty good, $800.

- Some long termist or EA fund managed by someone smart and sensible but with more bandwidth than Nick Beckstead, $600

- X-risk specific subset of Long Term Future is most of our expected value in that fund.

- Non-extinction risk long-run future

- Priorities research, $800

(Optional) Are there any ways that 80,000 Hours or other organisations in the community could help you get the talent or funding you need, which aren’t obvious, or they aren’t already doing?

- EA needs more gender and especially ethnic diversity.

- We’re going to need to meet a lot of angel investors as we start to spin out projects, which we would love to have some help with.

- Talent referrals would help. I also somehow forgot about the job board and didn’t think of putting my job on there, so I should probably do that.

- Maybe help coordinate moral trades

- Having some prestigious economist on 80k podcast to pitch global priorities research.

- No – 80k is already a known resource and strong ally when we need it, and what they’re doing day to day is already super helpful for our goals.

- Send us potential [staff members interested in the problem we’re working on]

- Send [us] names of awesome programmers!

If you’re still reading, you might be a good fit for a job at one of these organisations. Read more here and then get in touch.

Appendix 3 – Additional answers from animal and poverty focused organisations

(Optional) Do you think your answer to the question above is a good proxy indicator for your view on the relative cost-effectiveness of people in the community going to work on these 4 different ways of doing good?

Mean: 3.5/5

(Optional) What other hypothetical EA Fund do you think would be similarly effective, or more effective, than the ones above? What would it be focused on? In your view, a donation of $A to this fund would be equally as valuable as a $1,000 donation to the EA Community Fund.

- I don’t know if we need a new fund, but I think tailoring community building to focus especially on diversifying major funding sources and money in EA would be excellent (and not E2G, rather networking with already wealthy and influential people/foundations)

Mental health could be at least as effective as Global Health, though probably not as effective as EA Community or Animal Welfare. Acknowledging that I have done zero research on this, I’m guessing that $5,000 to mental health could ~ be equivalent to $1,000 to the EA Community Fund.

An explicit pro-veg fund, i.e. a fund with the aim to reduce the global consumption of animal products. The existing animal welfare fund focuses a lot on increasing animal welfare standards while there is a variety of benefits to the world by focusing on the reduction of animal products (climate change, public health, animal welfare, deforestation, etc.)

I believe a fund aimed at giving opportunities to influence policy in LMICs would be ~2x as cost-effective as the Global Health EA fund, although I’m not confident in this view

can’t think of any, but wish long term future fund can focus on other things like biosecurity or climate change (they are also long term future and don’t need separate funds)

Not necessarily more effective, but a Fund for advocacy and/or human rights. (A fund for present day humans which doesn’t focus primarily on health-related interventions).

(Totally optional) Any other comments on what we need more of in the community, or what characteristics or lack thereof most often hold people back from usefully contributing?

- Good social skills, especially in working with non-EAs; people willing to do work that isn’t status-advancing; people who are willing to make longer-term commitments to projects

Within animal welfare EA, effective management and operational skills are most lacking

I want to see more EA women and POC with extremely advanced, EA-based decision making skills in leadership positions within the animal welfare movement. We need more EAs in decision making positions in the animal welfare movement in general, but there’s a real thirst right now for more women and POC in light of #MeToo.

Social skills and trustworthiness

(Optional) Are there any ways that 80,000 Hours or other organisations in the community could help you get the talent or funding you need, which aren’t obvious, or they aren’t already doing?

- Write an in-depth career review of working in the plant-based and clean meat/egg/dairy sectors

I need more EAs who are extremely socially skilled in leadership (decision-making) positions in the animal welfare movement. I feel like animal welfare is a perceived as a little entry-level and “soft” compared to AI and X-Risk. Just because the concepts in animal welfare are easier to understand than AI doesn’t mean we don’t need really smart and skilled people working on this issue.

Make sure our job ads are being communicated to the community.

[Certain schools with good economics departments] have large amounts of high quality MA students going to work for J-PAL every year. Promoting these people to instead work for EA charities or doing more directly aligned work could be high value. J-PAL is increasingly becoming a more academic organization and many of these high quality candidates could help improve development charities. The gap between wanting to work for J-PAL or do direct work is not insurmountable either, so I believe the organization giving talks to these programs would sway some students towards working directly for standout development charities.

[For us,] help to get talent hasn’t yet been needed. However, for future higher management positions this could be very helpful, as we would like to tap into EA circles too.

How did you first get involved in effective altruism in-person/career-wise/taking real action? When did this happen?

| Working in animal rights | 2005 |

| Researched global health charities and decided to work in global health | 2010 |

| Switched into economics due to advice from 80k | 2013 |

| Worked on GWWC campaign | 2013 |

| Worked at Giving What We Can | 2015 |

| Personal giving and career at animal welfare charity | |

| Started to work at an animal welfare organisation | |

| Worked at a for profit organisation and gave away money + joined the board of a charitable organisation |

Additional charts on animal welfare and global poverty staff opinions on EA funds

Votes for most effective fund

Ties are counted as a partial vote for each fund.

| (n=12) | Original sample | Staff at additional animal orgs | Staff at additional global poverty orgs | Total from staff at additional object-level orgs | Total from original sample and additional object level orgs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EA Community Fund | 22% | 22% | 30% | 26% | 23% |

| Long-Term Future Fund | 67% | 14% | 30% | 21% | 54% |

| Animal Welfare Fund | 4% | 64% | 0% | 35% | 13% |

| Global Development Fund | 7% | 0% | 40% | 18% | 11% |

Votes for least effective fund

| (n=12) | Original sample | Staff at additional animal orgs | Staff at additional global poverty orgs | Total from staff at additional object-level orgs | Total from original sample and additional object level orgs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EA Community Fund | 0% | 8% | 10% | 9% | 3% |

| Long-Term Future Fund | 15% | 8% | 50% | 27% | 18% |

| Animal Welfare Fund | 22% | 0% | 20% | 9% | 18% |

| Global Development Fund | 63% | 83% | 20% | 55% | 61% |

Other responses by animal welfare and global poverty staff

For a typical recent Senior/Junior hire, how much financial compensation would you need to receive today, to make you indifferent about that person having to stop working for you or anyone for the next 3 years?1

| N=6 | Senior hire | Junior hire |

|---|---|---|

| Mean | $238,333 | $73,333 |

| Median | $275,000 | $37,500 |

| (n=9) | On a scale of 1 to 5 how constrained is your organisation by: | |

|---|---|---|

| Funding | Talent | |

| Mean | 2.6 | 3.6 |

| Minimum | 1 | 3 |

| Median | 3 | 3 |

| Maximum | 4 | 5 |

| How did you first get involved in effective altruism intellectually/online/agreeing with the ideas? How did you find out about EA? | |

| Personal contact | 4 |

| Peter Singer (article) | 2 |

| Already thought this way | 2 |

| Dylan Matthews article | 1 |

| The Life You Can Save (org) | 1 |

| ACE | 1 |

| The Life You Can Save (book) | 1 |

| Peter Singer (TED Talk) | 1 |

| GWWC | 1 |

| 80,000 Hours | 1 |

Notes and references

- We also tallied up the number of these staffers who thought each fund was best and worst.

Among the six animal welfare staffers, 1.3 (22%) thought the community fund was best, 0.8 (14%) thought the long-term future fund was best, 3.8 (64%) thought the animal fund was best, and none thought the global development fund was best (we again counted ties as a partial vote for each fund). Among the five global poverty staffers, 1.5 (30%) thought the community fund was best, 1.5 (30%) thought the long-term future fund was best, none thought the animal welfare fund was best, and 2 (40%) thought the global poverty fund was best. Overall, 47% of the staffers at these object level organisations thought the community fund or the long-term future fund was best.

We also looked into which fund various staffers thought were the worst. Among the six animal welfare staffers, 0.5 (8%) thought the community fund was worst, 0.5 (8%) thought the long-term future fund was worst, none thought the animal welfare fund was worst, and 5 (83%) thought the global development fund was worst. Among the five global poverty staffers, 0.5 (10%) thought the community fund was worst, 2.5 (50%) thought the long-term future fund was worst, 1 (20%) thought the animal welfare fund was worst, and 1 (20%) thought the global development fund was worst. Overall, 36% of these staffers thought the community fund or the long-term future fund was worst.↩