#46 – Philosopher Hilary Greaves on moral cluelessness, population ethics, probability within a multiverse, & harnessing the brainpower of academia to tackle the most important research questions

#46 – Philosopher Hilary Greaves on moral cluelessness, population ethics, probability within a multiverse, & harnessing the brainpower of academia to tackle the most important research questions

By Robert Wiblin and Keiran Harris · Published October 23rd, 2018

The barista gives you your coffee and change, and you walk away from the busy line. But you suddenly realise she gave you $1 less than she should have. Do you brush your way past the people now waiting, or just accept this as a dollar you’re never getting back? According to philosophy professor Hilary Greaves – Director of Oxford University’s Global Priorities Institute, which is hiring now – this simple decision will completely change the long-term future by altering the identities of almost all future generations.

How? Because by rushing back to the counter, you slightly change the timing of everything else people in line do during that day — including changing the timing of the interactions they have with everyone else. Eventually these causal links will reach someone who was going to conceive a child.

By causing a child to be conceived a few fractions of a second earlier or later, you change the sperm that fertilizes their egg, resulting in a totally different person. So asking for that $1 has now made the difference between all the things that this actual child will do in their life, and all the things that the merely possible child – who didn’t exist because of what you did – would have done if you decided not to worry about it.

As that child’s actions ripple out to everyone else who conceives down the generations, ultimately the entire human population will become different, all for the sake of your dollar. Will your choice cause a future Hitler to be born, or not to be born? Probably both!

Some find this concerning. The actual long term effects of your decisions are so unpredictable, it looks like you’re totally clueless about what’s going to lead to the best outcomes. It might lead to decision paralysis — you won’t be able to take any action at all.

Prof Greaves doesn’t share this concern for most real life decisions. If there’s no reasonable way to assign probabilities to far-future outcomes, then the possibility that you might make things better in completely unpredictable ways is more or less canceled out by the equally plausible possibility that you might make things worse in equally unpredictable ways.

But, if instead we’re talking about a decision that involves highly-structured, systematic reasons for thinking there might be a general tendency of your action to make things better or worse — for example if we increase economic growth — Prof Greaves says that we don’t get to just ignore the unforeseeable effects.

When there are complex arguments on both sides, it’s unclear what probabilities you should assign to this or that claim. Yet, given its importance, whether you should take the action in question actually does depend on figuring out these numbers.

So, what do we do?

Today’s episode blends philosophy with an exploration of the mission and research agenda of the Global Priorities Institute: to develop the effective altruism movement within academia. We cover:

- What’s the long term vision of the Global Priorities Institute?

- How controversial is the multiverse interpretation of quantum physics?

- What’s the best argument against academics just doing whatever they’re interested in?

- How strong is the case for long-termism? What are the best opposing arguments?

- Are economists getting convinced by philosophers on discount rates?

- Given moral uncertainty, how should population ethics affect our real life decisions?

- How should we think about archetypal decision theory problems?

- The value of exploratory vs. basic research

- Person affecting views of population ethics, fragile identities of future generations, and the non-identity problem

- Is Derek Parfit’s repugnant conclusion really repugnant? What’s the best vision of a life barely worth living?

- What are the consequences of cluelessness for those who based their donation advice on GiveWell style recommendations?

- How could reducing global catastrophic risk be a good cause for risk-averse people?

- What’s the core difficulty in forming proper credences?

- The value of subjecting EA ideas to academic scrutiny

- The influence of academia in society

- The merits of interdisciplinary work

- The case for why operations is so important in academia

- The trade off between working on important problems and advancing your career

Get this episode by subscribing to our podcast on the world’s most pressing problems and how to solve them: type 80,000 Hours into your podcasting app. Or read the transcript below.

The 80,000 Hours Podcast is produced by Keiran Harris.

Highlights

There are interestingly different types of thing that would count as a life barely worth living, at least three interestingly different types. It might make a big difference to somebody’s intuitions about how bad the repugnant conclusion is, which one of these they have in mind. The one that springs most easily to mind is a very drab existence where you live for a normal length of time, maybe say 80 years, but at every point in time you’re enjoying some mild pleasures. There’s nothing special happening. There’s nothing especially bad happening.

Parfit uses the phrase ‘muzak and potatoes’, like you’re listening to some really bad music, and you have a kind of adequate but really boring diet. That’s basically all that’s going on in your life. Maybe you get some small pleasure from eating these potatoes, but it’s not very much. There’s that kind of drab life.

A completely different thing that might count as a life barely worth living is an extremely short life. Suppose you live a life that’s pretty good while it lasts but it only lasts for one second, well, then you haven’t got time to clock up very much goodness in your life, so that’s probably barely worth living.

Alternatively you could live a life of massive ups and downs, so lots of absolutely amazing, fantastic things, lots of absolutely terrible, painful, torturous things, and then the balance between these two could work out so that the net sum is just positive. That would also count as a life barely worth living. It’s not clear that how repugnant the repugnant conclusion is is the same for those three very different ways of thinking about what these barely worth living lives actually amount to.

If you think, “I’m risk-averse with respect to the difference that I make, so I really want to be certain that I, in fact, make a difference to how well the world goes,” then it’s going to be a really bad idea by your lights to work on extinction risk mitigation, because either humanity is going to go extinct prematurely or it isn’t. What’s the chance that your contribution to the mitigation effort turns out to tip the balance? Well, it’s minuscule.

If you really want to do something in even the rough ballpark of maximizing the probability that you make some difference, then don’t work on extinction risk mitigation. But that line of reasoning only makes sense if the thing you are risk-averse with respect to was the difference that you make to how well the world goes. What we normally mean when we talk about risk aversion is something different. It’s not risk aversion with respect to the difference I make, it’s risk aversion with respect to something like how much value there is in the universe.

If you’re risk-averse in that sense, then you place more emphasis on avoiding very bad outcomes than somebody who is risk-neutral. It’s not at all counterintuitive, then, I would have thought, to see that you’re going to be more pro extinction risk mitigation.

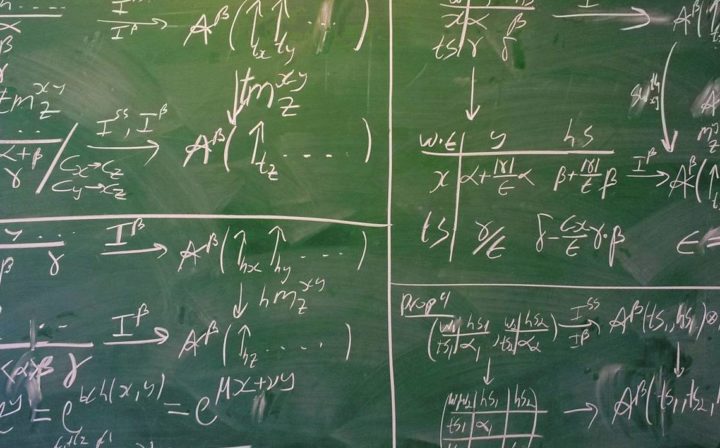

So the basic prima facie problem is, if you say, “Okay, I’m going to do this quantum measurement and the world is going to split. So possible outcome A is going to happen on one branch of the universe, and possible outcome B is going to happen on the second branch of the universe.” Then of course it looks like you can no longer say, “The probability of outcome A happening is a half,” like you used to want to say, because “Look, he just told me. The probability of outcome A happening is one, just like the probability of outcome B happening.” They’re both going to happen definitely on some branch or other of the universe.

Many of us ended up thinking the right way to think about this is maybe to take a step back and ask what we wanted from the notion, or we needed from the notion of probability in quantum mechanics in the first place, and I convinced myself at least that we didn’t in any particularly fundamental sense need that the chance of outcome A happening was a half. What we really needed was for it to be rational to assign weight one half to what would follow from outcome A happening. And it be rational to assign weight to one half to what would follow if and where outcome B happened. So if you have some measure over the set of actually future branches of the universe, and in a specifiable sense the outcome A branches total measure one half and the outcome B branches total measure one half, then we ended up arguing you’ve got everything you need from probability. This measure is enough, provided it plugs into decision theory in the right way.

Articles, books, and other media discussed in the show

Hilary Greaves’ papers:

- Review paper on population ethics: Population axiology

- Discounting for public policy: A survey

- Review article on Moral Cluelessness

- Justifying Conditionalization: Conditionalization Maximizes Expected Epistemic Utility

- Epistemic Decision Theory

- Moral uncertainty about population ethics with Toby Ord

- Research Agenda for the Global Priorities Institute

- Full list of Hilary’s publications

- Hilary’s professional site

Opportunities at the Global Priorities Institute:

- Up to date list of all opportunities

- Current vacancy: Head of Research Operations

- Summer Research Visitor Programme

- The Atkinson Scholarship

- The Parfit Scholarship

Everything else discussed in the show:

- Hilary’s talks on ‘Repugnant interventions‘ at EA Global Melbourne in 2015

- No Regrets by Frank Arntzenius on deliberational decision theory and game theory

- Pricing the Planet’s Future: The Economics of Discounting in an Uncertain World by Christian Gollier

- Person-affecting views and saturating counterpart relations by Christopher Meacham

Transcript

Robert Wiblin: Hi listeners, this is the 80,000 Hours Podcast, where each week we have an unusually in-depth conversation about the world’s most pressing problems and how you can use your career to solve them. I’m Rob Wiblin, Director of Research at 80,000 Hours.

Today’s interview with Hilary Greaves will be a blast for people who like philosophy or global priorities research. It’s especially useful to people who might want to do their own research into effective altruism at some point.

Before that I just wanted to flag a few opportunities at Hilary’s Global Priorities Institute, or GPI, that listeners might want to know about. If that’s not you, you can skip ahead 2 minutes.

GPI aims to conduct and promote world-class, foundational research on how to most effectively do good, in order to create a world in which global priorities are set by using evidence and reason.

To that end, GPI just started looking for a Head of Research Operations who’ll report directly to Hilary and will be responsible for all aspects of GPIs operations — including strategy, communications, finances and fundraising. They’re looking for someone with an analytic mindset, a demonstrated track record independently managing complex projects, and the ability to communicate and coordinate with others. It’s a 4 year contract, paying £40-49,000, and people can apply from anywhere in the world. Applications close the 19th of November, so you’ll want to get on that soon.

They also have a Summer Research Visitor Programme, and are looking for economists working on their PhD, or early in their career, who want to come visit the institute in summer 2019. Applications for that close 30th of November.

Both of these opportunities are advertised on their site, and of course we’ll link to them from the show notes and blog post.

GPI will also soon start advertising a series of postdoctoral fellowships and senior fellowships for both philosophers and economists, to start next September.

In the meantime they’re keen to explore the possibility of research positions with interested and qualified researchers. If you are a researcher in philosophy or economics who either already works on GPI’s research themes or is interested in transitioning into research in these areas, and you might be interested in working at or visiting GPI, please send a cover letter and CV to [email protected].

The above applies to everyone from Masters students through to emeritus professors.

Alright, on with the show – here’s Hilary.

Robert Wiblin: Today I’m speaking with Hilary Greaves. Hilary is a philosophy professor at the University of Oxford, and director of the Global Priorities Institute there. Besides issues in effective altruism and global priorities, her research interests include foundational issues in consequentialism, the debate between consequentialists and contractualists, issues of interpersonal aggregation, moral psychology and selective debunking arguments, the interface between ethics and economics, and formal epistemology. There’s quite a lot to talk about there, so thanks for coming on the podcast Hilary.

Hilary Greaves: Thanks for inviting me, it’s great to be here.

Robert Wiblin: So I hope to talk later about how people can potentially advance their careers in global priorities research and perhaps even work at the Global Priorities Institute itself, but first, what are you working on at the moment and why do you think it’s really important?

Hilary Greaves: Okay. So I’ve got three papers in the pipeline at the moment, all motivated more or less by effective altruist type concerns. One concerns moral uncertainty, this is the issue of what’s the right structural approach to making decisions when you’re uncertain about which normative claims are correct, or if you’re in any other sense torn between different normative views. And there I’m exploring a nonstandard approach that goes by the name of the Parliamentary Model, which is supposed to be an alternative to the standard expected value kind of way of thinking about how to deal with uncertainty. A second thing I’m doing is trying to make as rigorous and precise as possible the common effective altruist line of thought that claims that, in so far as you’re concerned with the long run impact of your actions rather than just, say, their impact within the next few years, you should be directing your efforts towards extinction risk mitigation, rather than any one of the other countless causes that you could be directing them towards instead.

Hilary Greaves: Then the third thing I’m doing is more a matter of methodology for cost-benefit analysis. Economists routinely use tools from cost-benefit analysis to make public policy recommendations. Typically, they do this by measuring how much a given change to the status quo would matter to each person, measured in monetary terms, and then adding up those amounts of money across people. Philosophers typically think that you shouldn’t just add up monetary amounts, you should first weight those monetary amounts according to how valuable money is to the person, and then sum up the result in weighted amounts across persons. And there’s a lively debate between philosophers and foundationally minded economists on the one hand, and lots of other economists – I should say, including lots of foundationally minded economists – on the other hand about whether or not one should apply these weights. So there’s a bunch of arguments in that space that I’m currently trying to get a lot clearer on.

Robert Wiblin: Right. So yeah, we’ll come back to a bunch of those issues later, but I noticed when doing some preparatory research for this episode that it seemed like you had a major shift in what you were focusing on for your research. You started out mostly in philosophy of physics, and now you’re almost entirely doing moral philosophy. Yeah, what caused you to make that shift and what were you looking at to begin with?

Hilary Greaves: So yeah, I originally did an undergraduate degree in physics and philosophy, and that’s how I got into philosophy. So I kind of by default ended up getting sucked into the philosophy of physics, because that was at the center of my undergraduate degree, and I did that for a while including my PhD. But I think it was always clear to me that the questions that had got me interested in philosophy more fundamentally, rather than just as part of my degree, were the questions that I faced in everyday practical life.

Hilary Greaves: What were the reasons for acting this way and that? How much sense did this rationale somebody was giving for some policy actually make? And then eventually, after working in research for a few years, I felt that I was just ticking the boxes of having an academic career by carrying on writing the next research article in philosophy of physics that spun off from my previous ones, and that really wasn’t a thing I wanted to do. I felt it was time now to go back to what had originally been my impetus for caring about philosophy, and start thinking about things that were more related to principles of human action.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. What exactly in philosophy of physics were you doing?

Hilary Greaves: So in philosophy of physics most of my research centered on the interpretation of quantum mechanics, where there are really confusing issues around how to think about what happens when a quantum measurement event occurs. So if you have some electron with some property and you want to measure this property, standard quantum mechanics will say that the system that you’re measuring proceeds according to one set of rules where nobody’s carrying out a measurement. But then when the experimental physicist comes along and makes a measurement, something totally different happens, some new rule of physics kicks in that only applies when measurements occur and doesn’t apply at any other time, and on a conceptual level this, of course, makes precisely no sense, because we know that measurements are just another class of physical interaction between two systems. So they have to obey the same laws of physics as every other physical process.

Hilary Greaves: So foundationalists of physics and philosophers of physics for a long time had tried to think about what the grand unifying theory could be that described quantum measurements without giving special status to measurements. One of the most prominent so called interpretations of quantum mechanics is the Many Worlds theory according to which, when a measurement occurs the world splits into multiple branches. And for complicated reasons this ends up being a story that makes sense without giving any fundamental status to the notion of measurement. It doesn’t sound like it does the way I put it but, honest, it does. So I got interested in this Many Worlds theory, and then I was working for quite a while on issues about how to make sense of probability within a many worlds theory, because probability is normally thought of as being absolutely central to quantum mechanics, but at first glance it looks like the notion of probability won’t any longer make sense if you go for a Many Worlds version of that theory.

Robert Wiblin: Alright. Yeah, how do you rescue probability? Is it a matter of there’s more worlds of one kind than another?

Hilary Greaves: Yeah, kind of. That’s what it ends up boiling down to, at least according to me. So the basic prima facie problem is, if you say, “Okay, I’m going to do this quantum measurement and the world is going to split. So possible outcome A is going to happen on one branch of the universe, and possible outcome B is going to happen on the second branch of the universe.” Then of course it looks like you can no longer say, “The probability of outcome A happening is a half,” like you used to want to say, because “Look, he just told me. The probability of outcome A happening is one, just like the probability of outcome B happening.” They’re both going to happen definitely on some branch or other of the universe.

Hilary Greaves: So yeah, many of us ended up thinking the right way to think about this is maybe to take a step back and ask what we wanted from the notion, or we needed from the notion of probability in quantum mechanics in the first place, and I convinced myself at least that we didn’t in any particularly fundamental sense need that the chance of outcome A happening was a half. What we really needed was for it to be rational to assign weight one half to what would follow from outcome A happening. And it be rational to assign weight to one half to what would follow if and where outcome B happened. So if you have some measure over the set of actually future branches of the universe, and in a specifiable sense the outcome A branches total measure one half and the outcome B branches total measure one half, then we ended up arguing you’ve got everything you need from probability. This measure is enough, provided it plugs into decision theory in the right way.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. How controversial is this multiverse interpretation?

Hilary Greaves: It depends what community your question is relativized to. I think among physicists it’s rather uncontroversial amongst physicists who have thought about the question at all, but possibly not for very good reasons. The thing that physicists get from Many Worlds quantum mechanics that they don’t get from any of the other things that are on the menu as options for a foundationally coherent interpretation of quantum mechanics is that you don’t have to change the existing equations of physics if you go for a many worlds interpretation. If you go for the other alternatives, so a so called pilot wave theory, or a dynamical collapse interpretation, you’re actually changing the physics in measurable ways.

Hilary Greaves: So if you’ve been through physics undergrad, and you’ve been through physics grad school, and you’ve built a career based on working with the existing equations of physics, then you’ve got an obvious reason to kind of like it, if you’ve got a coherent foundational story that’s consistent with all that stuff. So there’s that maybe not epistemically very weighty reason for physicists to prefer the many worlds interpretation, and a lot of them are very happy to go along with that. If you are instead asking about philosophers of physics, then it’s much more controversial and very much a minority view.

Robert Wiblin: Alright. What’s the argument for not thinking it’s a multiverse?

Hilary Greaves: Well, one of them is that probability doesn’t make sense.

Robert Wiblin: Okay.

Hilary Greaves: So like we said, [crosstalk 00:08:38].

Robert Wiblin: That also doesn’t seem very virtuous, yeah.

Hilary Greaves: Right. Yeah. I mean you’re asking the wrong person maybe for a sympathetic exposition of why people think this is a bad theory.

Robert Wiblin: Okay yeah, because you don’t hold this view. Does it seem-

Hilary Greaves: Also, I’ve been somewhat out of this field for the last ten years.

Robert Wiblin: Right, yeah.

Hilary Greaves: Back when I was working on this stuff, probability was one of the main bones of contention. I ended up kind of feeling that I and my co-researchers had solved that problem and moved on, but then I stopped listening to the rest of the debate. So I don’t know how many people are now convinced by that stuff.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. Do you feel like it’s an open and shut case from your point of view? Setting aside the fact that, of course, other smart people disagree, so you’ve got to take their view seriously. If it was just your perspective, would it be pretty clear that it’s multiverse?

Hilary Greaves: So the statement that I am willing to make confidently in this area is I don’t think that considerations of probability generate any difficulty whatsoever for the multiverse theory. There’s some other stuff that I think is more subtle, and actually to my mind more interesting, about exactly what’s the status of the branching structure and how it’s defined in the first place. I ultimately think that’s probably not problematic either, but I think there are a lot of things there that could be helpfully spelled out more clearly than they usually are, and I think the probability stuff is, yes, an open and shut case.

Robert Wiblin: So it sounds like you’ve made a pretty major switch in your research focus. How hard is that, and how uncommon is that in academia?

Hilary Greaves: Good question. Yeah, it’s quite uncommon, and the career incentives quite clearly explain why it would be uncommon, because academia very much rewards lots of publications, lots of high quality publications, and if you’ve already got a research career going in one area, it’s always quite easy to generate another equally high quality paper following on the line of research that you already embarked on. Whereas, if you switch to a totally different area, as I did and as many others have done, there’s a pretty long fallow period where you’re basically reduced to the status of a first year graduate student again, and when people ask you, “What are you working on?” Your answer is no longer, “Oh, I’ve got three papers that are about to be published on X, Y, and Z.” And it’s more, “Uh, I’m not really working on anything as such right now. I’m just kind of looking around, learning some new things.”

Hilary Greaves: So I had a quite embarrassing period of two or three years where I would try and avoid like the plague situations where people would ask me what I was working on, because I felt like the only answer I had available was not appropriate to my level of seniority, since I was already tenured. So in that sense, it’s kind of tricky, but I think if it’s something that you really want to do, and if you’re willing to bear with that fallow period, and if in addition you’re confident, or maybe arrogant enough to have this brazen belief that your success is not localized to one area of academia, you’re just a smart enough person that you’ll be successful at whatever you take on, so this is not a risk, it’s just a matter of time, then it’s definitely something that you can do.

Hilary Greaves: And I’d encourage more people to do it because, at the end of the day, if you’re not working on the things that you’re excited about, or the things that you think are important, then you might as well not be in academia. There are lots of other more valuable things you could do elsewhere.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. Did you deliberately wait until you had tenure to make the switch? Would you recommend that other people do that?

Hilary Greaves: In my case it was, honestly, it was not deliberate. And because of that I feel it would be a bit inappropriate for me to try and advise people who don’t yet have tenure whether they should do a similar thing, because it definitely slows down your publication record for a good few years.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. That just puts you at risk of not being able to stay in.

Hilary Greaves: Yeah. I mean there’s a kind of halfway house you could go for, where you keep up your existing line of research, but you devote some significant proportion of your time to side projects. That’s the model that I’ve seen lots of graduate students successfully pursue. And I think that’s probably good, even from a purely careerist perspective, in that you end up much more well rounded, you end up knowing about more things, having a wider network of contacts and so forth, than if you just had your narrow main research area and nothing else.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. Do you think you learned any other lessons that would be relevant to people who want to switch into doing global priorities research but aren’t currently in it?

Hilary Greaves: Maybe depends what other thing they are currently in. I did find that some of the other areas of research, some of the particular other areas of research that I happened to have worked in previously, involved learning stuff that usefully transferred into doing global priorities research, like my work in both philosophy of physics and formal epistemology had given me a pretty thorough grounding in decision theory that’s been really useful for working in global priorities research and, at a more abstract level, having worked in physics meant that I was coming into global priorities research with a much stronger mathematics background than a philosopher typically might have, and one thing that’s meant is that it’s been much easier for me to dive into interdisciplinary work with economists than some other philosophers might find it. But these reasons are quite idiosyncratic to the particular things I did before. I’d expect that you’d always find particular things from your other area of research that were useful, they’d just be different things obviously, if you had a different previous background area.

Robert Wiblin: So yeah, what is formal epistemology?

Hilary Greaves: So formal epistemology in practice more or less lines up with a Bayesian way of thinking about belief formation. Where, instead of thinking in terms of all out beliefe, like, “I believe that it’s raining,” or “I believe that it’s not raining”, you talk instead about degrees of belief. So this is most natural in the case of things like weather forecasts, where it’s very natural to think in probabilistic terms. You know, if the question is not whether it’s raining now, but whether it will rain tomorrow, weather forecasters typically won’t say, “It will rain tomorrow.” Or, “It won’t rain tomorrow.” They say, “The chance of it raining tomorrow is 30%.” Or whatever. So in Bayesian terms, you would report your degree of belief that it will rain tomorrow as being 0.3 in that kind of context.

Hilary Greaves: So then formal epistemology is concerned with the rules that govern what these numbers should be and how they should evolve over time. Like if you get a new piece of information, how should your degree of belief numbers change over time? So the work I did on formal epistemology was mostly on a bunch of structural questions about how these degrees of belief should be organized, and how you justify the normative principles that most people think are correct about how they should be organized.

Robert Wiblin: So, isn’t it just Bayes’ theorem? I guess there’s challenges choosing priors, but what are the open questions in formal epistemology?

Hilary Greaves: Okay. So Bayes’ theorem itself is just a trivial bit of algebra. The nontrivial thing in the vicinity is the principle of conditionalization, which says that, “Here’s the right way to update your degrees of belief when you get a new bit of evidence, you move from whatever your old credence function was to the one that you get by conditionalizing on the new bit of evidence, and we can write down the mathematical formula that says exactly what that means.” So there’s widespread agreement that, at least in normal cases, that is in fact the rational way to update your degrees of belief. There’s much less agreement about precisely why it’s the rational way to update your degrees of belief. So yeah, we all get the sense that if somebody updates in a completely different way, they’re weird, they’re irrational, there’s something wrong with them. But instead of just slinging mud, we’d like to have something concrete to say about why they’re irrational or what’s wrong with them.

Hilary Greaves: So some of the early work I did on formal epistemology was exploring that question, and I tried to provide, well I guess I did provide, a decision theoretic argument based on the idea of expected utility, but importantly expected epistemic utility, rather than expected practical utility, we could say a bit more about that difference in a minute, for why conditionalization is the uniquely rational updating rule. Basically, the idea was, “Okay, if what you’re trying to do is end up with degrees of belief that are as accurate as possible, they conform to the facts as closely as possible, but you know you’re proceeding under conditions of uncertainty. So you can’t guarantee that your degrees of belief are going to end up accurate.” If you take a standard decision theoretic approach to dealing with this uncertainty, where you’re trying to maximize expected value, but here it’s expected value in the sense of expected closeness to the truth, a coauthor and I were able to prove that conditionalization was the updating rule for you. Any other updating rule will perform worse than conditionalization in expected epistemic value terms.

Robert Wiblin: Interesting. Okay, so normally you have decision theory that’s trying to maximize expected value where you might think about something like moral value, or like prudential value, like getting the things that you want. But here you’ve redefined the goal as maximizing some kind of epistemic expected value, which is like having beliefs or credences that are in correspondence with the world as much as possible, or whereas your errors are minimized.

Hilary Greaves: That’s right, yeah. So just to be clear, the claim is not that, “This should be your goal. You should live your life in such a way as to maximize and to bring a fit between your beliefs and the truth.” That would be a crazy principle. The thought was more, “Actually what we have in play here are two different notions of rationality.” There’s something like practical or prudential rationality, which is the way we normally think about maximizing value. You just decide what the stuff is that you care about and you try to maximize the expected quantity of that thing. That’s the normal notion of rationality. But on reflection it seems that we also have a second notion of rationality, which you might call epistemic rationality, which is about having your beliefs respond to the evidence in the intuitively correct kind of ways, and we wanted to work out what are the principles of this epistemic rationality thing, even when doing what’s epistemically rational might in fact conflict with doing what’s practically rational.

Robert Wiblin: Okay. Well, we’ll stick up a link to that paper. It’s epistemic decision theory, right?

Hilary Greaves: No, that paper is the 2006 one, Conditionalization Maximizes Expected Epistemic Utility.

Robert Wiblin: Oh, okay. And then the later paper on epistemic decision theory, is that just more of the same kind of thing, or is that a different argument?

Hilary Greaves: It’s different. It’s related. So there the issue was, when we think about practical decision theory, there are some cute puzzle cases where it’s not obvious precisely what notion of expected utility we ought to be trying to maximize. So for the cognoscenti here, I’m talking about things like the Newcomb problem, where there’s one action that would cause the world to get better, but would provide evidence that the world is already bad, and there people’s intuitions go different ways on whether it’s rational to do this action. Like, do you want to do the thing that gives you evidence that you’re in a good world, or do you want to do the thing that makes the world better, even if it makes it better from a really bad starting point? So this debate had already been reasonably mapped out in the context of practical decision theory, and what I do in the epistemic decision theory paper is explore the analogous issues for the notion of epistemic rationality.

Hilary Greaves: So I’m asking questions like, okay, we know that we can have causal and evidential decision theory in the practical domain. Let’s write down what causal and evidential decision theory would look like in the epistemic domain, and let’s ask the question of which of them, if either, maps on to our intuitive notion of epistemic rationality. And the kind of depressing conclusion that I get to in the paper is that none of the decision theories we’ve developed for the practical domain seem to have the property that the analog of that one performs very well in the epistemic domain.

Hilary Greaves: I say this is a kind of depressing conclusion because it seems like, in order to be thinking about epistemic rationality in terms of trying to get to good epistemic states, like trying to get to closeness to the truth or something like that, you have to have a decision theory corresponding to the notion of epistemic rationality. So if you can’t find any decision theory that seems to correspond to the notion of epistemic rationality, that seems to suggest that our notion of epistemic rationality is not a consequentialist type notion, it’s not about trying to get to good states in any sense of good states, and I at least found that quite an unpalatable conclusion.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. So just for the people who haven’t really heard about decision theory, could you explain what are the kind of archetypal problems here that make it an interesting philosophical issue?

Hilary Greaves: Sure, okay. So there’s a well known in the field problem called the Newcomb problem, which pulls apart two kinds of decision theory, which in normal decision situations would yield the same predictions as one another about what you should do. So normally you don’t have to choose between these two different things, and normally don’t realize that there are two different decision theories, maybe at the back of your mind, but here’s the Newcomb problem, and hopefully this will help people to see why there’s a choice to be made.

Hilary Greaves: So, suppose you find yourself in the following, admittedly very unusual, situation; you’re confronted with two boxes on the table in front of you. One of these boxes is made of glass, it’s transparent, you can see what’s in it, and the other one is opaque. So you can see that the transparent box contains a thousand pounds. What you know about the opaque box is that either it’s empty, it’s got no money in it at all, or otherwise it contains a million pounds, and for some reason you’re being offered the following decision. You either take just the opaque box, so you get either nothing or the million pounds in that case and you don’t know which, or you take both boxes. So you get whatever’s in the opaque box, if anything, and in addition the thousand pounds from the transparent box. But there’s a catch, and the catch concerns what you know about how it was decided whether to put anything in the opaque box.

Hilary Greaves: The mechanism for that was as follows; there’s an extremely smart person who’s a very reliable predictor of your decisions, and this person yesterday predicted whether you were going to decide to take both boxes or only the opaque box, and if this predictor predicted you’d take both boxes, then she put nothing in the opaque box. Whereas, if she predicted that you would take only the opaque box, then she put a million pounds in that box. Okay, so knowing that stuff about how the predictor decided what, if anything, to put in the opaque box, now what do we think about whether you should take both boxes or only the opaque one? And on reflection you’re likely to feel yourself pulled in two directions.

Hilary Greaves: The first direction says, “Well, look, this stuff about whether there’s anything in the opaque box or not, that’s already settled, that’s in the past, there’s nothing I can do about it now, so I’m going to get either nothing or the million pounds from that box anyway, and if in addition I take the transparent box, then I’m going to get a thousand pounds extra either way. So clearly I should take both boxes, because whether I’m in the good state or the bad state, I’m going to get a thousand pounds extra if I take both boxes.”

Hilary Greaves: So that’s one intuition, but the other intuition we can’t help having is, “Well, hang on, you told me this predictor was extremely reliable, so if I take both boxes it’s overwhelmingly likely the predictor would have predicted that I’ll take both boxes, so it’s overwhelmingly likely then that the opaque box is empty, and so it’s overwhelmingly likely that I’ll end up with just a thousand pounds. Whereas, if I take only the opaque box then there’s an overwhelming probability the predictor would have predicted that, so there’s an overwhelming probability in that case that I’ll end up with a million pounds. So surely I just do the action that’s overwhelmingly likely to give me a million pounds, not the one that’s overwhelmingly likely to give me a thousand pounds.”

Hilary Greaves: So, corresponding to those two intuitions, we have two different types of decision theory. One that captures the first intuition, and one that captures the second. So the decision theory that says you should take both boxes is called causal decision theory because it’s concerned with what your actions causally bring about. Your actions in this case, if you take both boxes, that causally brings about that you get more money than you otherwise would have. Whereas, if you say you should only take the one box, then you’re following evidential decision theory, because you’re choosing the action that is evidence for the world already being set up in a way that’s more to your favor.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. So what do you make of this?

Hilary Greaves: Well, I’m a causal decision theorist, and most people who’ve thought about this problem a lot, I think it’s fair to say, are causal decision theorists, but that’s by no means a universal thing. This problem remains controversial.

Robert Wiblin: So, my amateurish attitude to this is, well, causal decision theory seems like the right fundamental decision theory, but in particular circumstances you might want to pre-commit yourself to follow a different decision theory on causal grounds, because you’ll get a higher reward if you follow that kind of process.

Hilary Greaves: Yeah.

Robert Wiblin: Does that sound plausible?

Hilary Greaves: It’s definitely plausible. I mean, pre-committing to follow decision theory X is not the same action as doing the thing that’s recommended by decision theory X at some later time. So it’s completely consistent to say that, like in the Newcomb problem for example, if I knew that tomorrow I was going to face a Newcomb situation, and I could pre-commit now to following evidential decision theory henceforth, and if in addition the predictor in this story is going to make their decision about what to put in the box after now, then definitely, on causal decision theory grounds, it’s rational for me to pre commit to evidential decision theory, that’s completely consistent.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. So I find all of this a little bit confusing, because I guess I don’t quite understand what people still find interesting here. But I guess if you’re programming an AI, maybe this comes up a lot, because you’re trying to figure out what should you pre-commit to, what kind of odd situations like this might arise the most such that maybe you should program an agent to deviate from causal decision theory, or seemingly deviate from causal decision theory, in order to get higher rewards.

Hilary Greaves: Yeah, that seems right. I think the benefit that you get from having been through this thought process, if you’re theorizing in the AI space, is that you get these insights like that it’s crucial to distinguish between the act of following a decision theory and the act of pre-committing to follow that decision theory in future. If you’ve got that conceptual toolbox that pulls apart all these things, then you can see what the crucial questions are and what the possible answers to them are. I think that’s the value of having this decision theoretic background.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. There are a few other cases that I find more amusing, or maybe more compelling, because they don’t seem to involve some kind of reverse causation or backwards causation in time.

Hilary Greaves: Wait, hang on, can I interrupt there?

Robert Wiblin: Oh, go for it, yeah.

Hilary Greaves: There’s no backwards causation in this story. That’s important.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah.

Hilary Greaves: But, you know, I’m quite good at predicting your actions. For example, I know you’re going to drink coffee within the next 10 minutes. There’s nothing sci-fi about being able to predict people’s decisions and, by the way, you’re probably now in a pretty good position to predict that I would two-box if I faced the Newcomb problem tomorrow.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah.

Hilary Greaves: You are very smart, but you didn’t have to be very smart to be in a position to make that prediction.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah.

Hilary Greaves: So there’s nothing … People often feel the Newcomb problem involves something massively science fictional, but it’s really quite mundane actually. It’s unusual, but it doesn’t involve any special powers.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah, okay. So I agree with that. On paper, it doesn’t involve any backwards causation, but I guess I feel like it’s messing with our intuitions, because you have this sense that your choice of which boxes to pick is going to cause somehow, like backwards in time, cause them to have put a different amount of money in the box. So I feel like that’s part of why it seems so difficult, it because it’s like it’s building into it this intuition that you’re causing, that you can effect today what happened yesterday. Do you see what I’m getting at? I guess if you totally disavow that-

Hilary Greaves: I think I see what you’re getting at, I just don’t think that’s a correct description of … I mean, maybe you’re right as a matter of psychology that lots of people feel that’s what’s going on in the Newcomb problem, I just want to insist that it is not in fact [crosstalk 00:27:28].

Robert Wiblin: That’s not how it’s set up. Okay, yeah. But other ones where I feel you don’t get that effect as much is the smoking lesion problem and also the psychopath button. Do you just want to explain those two quickly, if you can?

Hilary Greaves: So the smoking lesion I think is structurally very similar to the Newcomb problem, it just puts different content in the story. So the idea here is there are two genetic types of people. One type person has the smoking lesion and the other type of person does not have the smoking lesion. What the smoking lesion predisposes you to, if you have it, is two things. Firstly, it makes it more likely that you’ll choose to smoke, and secondly it makes it more likely that you’ll get cancer, and in this story smoking does not cause cancer, and you know all of this stuff. Your decision in that problem is whether or not to smoke. And there you could have the same two intuitions as the ones I described in the Newcomb problem.

Hilary Greaves: You could think, “Well, I should smoke because, look, either I’ve got the smoking lesion or not, and nothing I do is going to change that fact and I happen to enjoy smoking, so it’s just strictly better for me either way to smoke than not.” That’s the causal decision theorist intuition. Or here the evidential decision theorist’s intuition would be, “No, I really don’t want to smoke, because look, if I smoke then probably I’ve got this lesion-

Robert Wiblin: It’s lowering my life expectancy.

Hilary Greaves: And if I’ve got this lesion, then probably I’ll get cancer. So probably if I smoke I’ll get cancer, and that’s bad. So I’d better not smoke.” I think in that problem, to my intuition, the evidential intuition theorist’s story sounds less intuitively plausible, but I’m not sure why that’s the case.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. It’s funny because the idea is that smoking in this case doesn’t in fact lower your life expectancy, but it lowers your expectancy of how long you’re going to live.

Hilary Greaves: According to one notion of expectancy, yeah.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. So in that case you feel like it’s just more straightforwardly intuitive to do the causal thing?

Hilary Greaves: That’s my gut reaction to that case, yeah. I don’t know how widely shared that is.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah, and the psychopath button?

Hilary Greaves: Alright so, in the psychopath button case, imagine that there’s a button in front of you, and what this button does if you press it is that it causes all psychopaths in the world to die. This may, by the way, include you, if you turn out to be a psychopath, but you’re not sure whether you are a psychopath or not. Your decision is whether or not to press this button and your preferences are as follows; you’d really like to kill all the psychopaths in the world, provided you’re not one of them, but you definitely don’t want to kill all psychopaths in the world if you’re one of them. That’s a price that’s too high to be worth paying by your likes. You currently have very low credence that you’re a psychopath, but the catch is you have very high credence that only a psychopath would press this kind of button.

Hilary Greaves: Okay, so now your decision is whether to press this button or not, and the problem is that you seem to be caught in a loop. So if you press the button then, after updating on the fact that you decided to press the button, you have high credence that you’re a psychopath, so then you have high credence that pressing this button is going to kill you, as well as all the other psychopaths. So you have high credence that this is a really bad idea. After conditionalizing on the fact that you’ve decided to press the button, deciding to press the button looks like a really bad decision. But, similarly, if you conditionalize on your having decided not to press the button then, by the epistemic license that you then have, that also looks like a really bad idea, because if you decided not to press the button then you have very low credence that you’re a psychopath, and so you think pressing the button has much higher expected value than not pressing it.

Hilary Greaves: So it looks like, either decision you make, after you conditionalize on the fact that you’ve made that decision, you think it was a really bad decision.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. What do you make of that one? Because in that case it feels like you shouldn’t press the button, to me.

Hilary Greaves: Yeah. I think this is a decision problem where it’s much less obvious what the right thing to say is. I’m kind of enamored of some interesting work by people like Frank Arntzenius who’ve argued that, in this case, you have to expand your conception of the available acts beyond just press the button and not press the button, and admit some kind of mixture where the equilibrium can be do something that leads to pressing the button with probability one third, or something like that. So Arntzenius’ work argues that, once you’ve got those mixed acts in your space, you can find stable points where you continue to endorse the mixed acting question, even after having conditionalized on the fact that that’s your plan.

Robert Wiblin: Interesting. So this is like when you pre-commit to some probability of doing it?

Hilary Greaves: Yeah. There are things that are deeply unsatisfying about that route, but I’m not sure the alternatives are very much better. We’re now into the space of interesting open problems in decision theory.

Robert Wiblin: So what is the cutting edge here, and are there other decision theories besides causal decision theory or evidential decision theory that you think have something going for them?

Hilary Greaves: Yeah, there’s a few others. So Ralph Wedgwood, one of my colleagues, well, used to be one of my colleagues at Oxford, developed a decision theory called benchmark decision theory, which is supposed to be a competitor to both causal and evidential decision theory. The paper by Frank Arntzenius I just alluded to, explores what he calls ‘deliberational variants’ on existing decision theories, in response to cases like the psychopath button. These are formalizations of what the decision theory looks like in this richer space of mixed acts.

Hilary Greaves: Then as many of your listeners will know, in the space of AI research, people have been throwing around terms like ‘functional decision theory’ and ‘timeless decision theory’ and ‘updateless decision theory’. I think it’s a lot less clear exactly what these putative alternatives are supposed to be. The literature on those kinds of decision theories hasn’t been written up with the level of precision and rigor that characterizes the discussion of causal and evidential decision theory. So it’s a little bit unclear, at least to my likes, whether there’s genuinely a competitor to decision theory on the table there, or just some intriguing ideas that might one day in the future lead to a rigorous alternative.

Robert Wiblin: Okay, cool. Well, hopefully at some point in the future we might do a whole episode just on decision theory, where we can really dive into the pros and cons of each of those. But just to back up, so you were trying to then draw an analogy between these decision theories and epistemic decision theory, and then you found that you couldn’t make it work, is that right?

Hilary Greaves: So I think the following thing is the case. For any decision theory you can write down in the practical case, you can write down a structurally analogous decision theory in the epistemic case. However, there’s no guarantee that the assessment of whether such and such a decision theory fits our intuitions about what’s rational, but there’s no guarantee that those assessments are going to be the same in the practical and the epistemic case. So it could, for example, be that when we’re thinking about practical rationality, our intuitions scream out that causal decision theory is the right approach, but when we’re thinking about epistemic rationality our intuitions scream out that somebody who updates their beliefs according to causal epistemic decision theory is behaving in a way that’s wildly epistemically irrational. There can be that kind of difference.

Hilary Greaves: So there’s the same menu of decision theory options on the table in both cases, but the plausibility of the decision theories might not match, and what I was worried about and maybe concluded in the epistemic case, is that all the decision theories you can write down, by writing down the structural analog of all the existing ones in the practical domain, when you write down the analogs in the epistemic domain, none of them does a very good job of matching what seemed to be our intuitions about how the intuitive notion of epistemic rationality works. So then I just got very puzzled about what our intuitive notion of epistemic rationality was up to, and why and how we had a notion of rationality that behaved in that way, and that kind of thing.

Robert Wiblin: Is there an intuitive explanation of what goes wrong with just causal epistemic decision theory?

Hilary Greaves: Okay, so here’s a puzzle case that I think shows that a causal epistemic decision theory fails to match the way most people’s intuitions behave about what’s actually epistemically rational versus not. So, suppose you’re going for a walk and you can see clearly in front of you a child playing on the grass. And suppose you know that just around the corner, in let’s say some kind of playhouse, there are 10 further children. Each of these additional children might or might not come out to join the first one on the grass in a minute. Suppose though … This example is science fictional, so you have to bear with that. Suppose these 10 further children that are currently around the corner are able to read your mind, and the way they’re going to decide whether or not to come out and play in a minute depends on what beliefs you yourself decide to form now.

Hilary Greaves: So, one thing you have to decide now about what degrees of belief to form is what’s your degree of belief that there is now a child in front of you playing on the grass. So, recall the setup. The setup specified that there is one there. You can see her. She’s definitely there. So, our intuitive notion of epistemic rationality, I take it, entails that it’s epistemically rational – you’re epistemically required – to have degree of belief one basically, or very close to it, that there’s currently a child in front of you.

Hilary Greaves: But, like in all these cases, there’s going to be a catch. The catch here is that if you form a degree of belief one, as arguably you should or something very close to it, that there’s a child in front of you now, then what each of these 10 additional children are going to do is they’re going to flip a coin. And they’ll come out to play if their coin lands heads, they’ll stay inside and not come out if their coin lands tails. Whereas if you formed a degree of belief zero that there’s a child in front of you now, then each of these additional 10 ones will definitely come out to play.

Hilary Greaves: And suppose that you know all this stuff about the setup. Then it looks as though causal epistemic decision theory is going to tell you the rational thing to do is to have degree of belief zero that there’s a child in front of you now, despite the fact that you can see that there in fact is one, and the reason is the way this scenario is being setup, the way I stipulated it, if you form degree of belief zero that there’s a child in front of you now, then you know with probability one, there are going to be 10 more children there in a minute. So, you can safely form degree of belief one in all those other children being there in a minute’s time. So, when we assess your epistemic state overall, yeah, you get some negative points in accuracy terms for your belief about the first child, but you’re guaranteed to get full marks regarding your epistemic state about those 10 other children whereas, if you do the intuitively epistemically rational thing and you have degree of belief one that there’s a child in front of you now, then it’s a matter of randomness for each of the other 10 children whether they come out or not.

Hilary Greaves: So, the best you can do is kind of hedge your bets and have degree of belief a half for either of the other 10 children. But you know you’re not gonna get very good epistemic marks for that because, whether they come out to play or not, you’ll only get half marks. So, when we assess your overall epistemic state, it’s gonna be better in the case where you do the intuitively irrational thing than the case where you do the intuitively rational thing. But causal epistemic decision theory, it seems, is committed to assessing your belief state in this global kind of way. Because what you wanted to maximize, I take it, was the total accuracy, the total degree effect between your beliefs about everything and the truth.

Hilary Greaves: So, I’ve got a kind of mismatch that at least I couldn’t see anyway of erasing by any remotely minor tweak to causal epistemic decision theory.

Robert Wiblin: So, it boils down to: if you form a false belief now, like a small false belief, then the world will become easier to predict, and so you’ll be able to forecast what’s going on or have more accurate beliefs in the future. So, you pay a small cost now for more accurate beliefs in the future whereas, if you believe the true thing now which in some sense seems to be the rational thing to do, then you’ll do worse later on because the world’s become more chaotic.

Hilary Greaves: It’s kind of like that. There’s an inaccuracy in what you just said, which was important for me, but I don’t know if this is getting into nitty gritty researcher’s pedantry. The thing that for me is importantly inaccurate about what you just said is it’s not about having inaccurate beliefs now but then getting accurate beliefs in the future, because if that were the only problem, then you could just stipulate, “Look, this decision theory is just optimizing for-”

Robert Wiblin: The present.

Hilary Greaves: ” … accurate beliefs now.” So, actually what you’re having to decide now is both things. So, you have to decide now what’s your degree of belief now that there’s a child in front of you, and also what’s your degree of belief now about whether there will be further children there in a minute. So, all the questions are at your beliefs now, and that’s why there’s no kind of easy block to making the trade off that seems intuitively problematic.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. Are you still working on this epistemic decision theory stuff? Or have you kind of moved on?

Hilary Greaves: No. This is a paper from about five years ago and I’ve since moved much more in the direction of papers that are more directly related to effective altruism, global priorities type concerns.

Robert Wiblin: Okay. Yeah. Is anyone carrying the torch forward? Do you think it matters very much?

Hilary Greaves: I think it matters in the same way that this more abstract theoretical research ever matters, and I just tell the standard boring story about how and why that does matter, like … These abstract domains of inquiry generate insights. Every now and then, those insights turn out to be practically relevant in surprising ways. You can’t forecast them, but experience shows there are lots of them. You can tell that kind of story and I think it applies here as well as it does everywhere else. I don’t think there’s anything unusually practically relevant about this domain compared to other domains of abstract theoretical inquiry. If I did, I might still be working on it.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. This may be a bit of a diversion, but what do you think of that kind of academic’s plea that, whatever they’re looking into, who can say how useful, all basic research is useful and they should just do whatever they’re most interested in?

Hilary Greaves: I think it is implausible if it’s supposed to be an answer to the question, “What’s the thing you could do with your life that has the highest expected value?” But I think it is right as an answer to a question like-

Robert Wiblin: “Why is this of some value?”

Hilary Greaves: Yeah. Why should the public fund this at all, or that kind of question.

Robert Wiblin: Do you have a view on whether we should be doing kind of more of this basic exploratory research where the value isn’t clear? Or more applied research where the value is very clear, but perhaps the upper tail is more cut off?

Hilary Greaves: Yeah. I mean, it depends partly on who “we” is. One interpretation of your question would be do I think the effective altruist community should be doing more basic research, and there I think the answer is definitely yes. And that’s why the Global Priorities Institute exists. That’s kind of our, one way of describing the most basic level of what we take our brief to be is take issues that are interesting and important by effective altruists lights and submit them to the kind of critical scrutiny and intellectual rigor that’s characteristic of academia rather than just writing them up on effective altruist blogs and not getting them into the academic literature, or not doing the thing where you spend one year perfecting one footnote to work out exactly how it’s meant to go. We tend to do more that last kind of thing.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. Okay. Well, let’s push on and talk about the kind of research that you’re doing now. What are the main topics that you’re looking into and that GPI’s looking into? Or at least that you have been looking into over the last few years?

Hilary Greaves: Sure. GPI’s existed for maybe a year. It’s officially existed for a bit less than that, but that’s roughly the time scale in which we’ve had people working more or less full time on GPI issues. And the first thing we did was drew up a monstrous research agenda where we initially tried to write down every topic we can think of where we thought there was scope for somebody to write an academic research article making rigorous either an existing current of thought in the effective altruist community where effective altruists have kind of decided what they think they believe, but the argument hasn’t been made fully rigorous or there’s an interesting open question where effective altruists really don’t know and don’t even think they know what the answer is, but it seems plausible that the tools of various academic disciplines, and we’re especially interested in philosophy and economics, might be brought to bear to give some guidance on what’s a more versus a less plausible answer to this practically important question.

Hilary Greaves: So, through that lens, we ended up with something like a 50 page document of possible research topics. So, clearly we had to prioritize within that. What we’ve been focusing on in the initial sort of six to eight months is what we call the long term-ism paradigm where long term-ism would be something like the view that the vast majority of the value of our actions, or at least our highest expected value actions, the vast majority of the value of those actions lies in the far future rather than in the nearer term. So, we’re interested in what it looks like when you make the strongest case you can for that claim, and then also what follows from that claim and how rigorous can we make the arguments about what follows from that claim.

Hilary Greaves: So for example, lots of people in the EA community thing that, in so far as you accept long term-ism, what you should be focusing on is reducing risks of premature human extinction rather than, for example, trying to speed up economic progress. But nobody to my knowledge has really tried to rigorously sit down and write down why that’s the case. So, that’s one of the things we’ve been trying to do.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. How strong do you think the case is for long term-ism? It sounds like you’re sympathetic to it, but how likely do you think it might be that you could change your mind?

Hilary Greaves: Okay, yeah. Definitely sympathetic to it. I’m a little bit wary of answering the question about how likely is it that I think I might change my mind, because even trying to predict that can sometimes psychologically have the effect of closing one’s mind as a researcher and reducing one’s ability to just follow an argument where it leads.

Robert Wiblin: I see.

Hilary Greaves: So, I’m much more comfortable in the frame of mind where I think, “Yeah, okay. Roughly speaking, I find this claim very plausible, but I know as a general matter that when I do serious research, when I sit down, try and make things fully rigorous, I end up in some quite surprising places, but it’s very important that, while I’m in that process, I’m in a frame of mind of just following an argument wherever it leads rather than some kind of partisan motivated cognition.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah.

Hilary Greaves: So, yeah. I think it’s extremely likely that I’ll change my mind on many aspects of how to think about the problem. I don’t really know how to predict what’s the probability I’ll change my mind on the eventual conclusion.

Robert Wiblin: Sure. I guess, what are the main controversies here? What are maybe the weakest points that people kind of push on if they’re wanting to question long term-ism?

Hilary Greaves: Okay. One thing that’s controversial is how to think about discounting future welfare. So, it’s very common in economic analyses of policy recommendations, for example, to at least discount future goods, and that’s very clearly also the right thing to do, by the way, because if you think that people are going to be richer in the future, then a marginal unit of concrete material goods has less value in the future than it does today, just because of considerations of diminishing marginal utility. If you think people are going to be poorer in the future, then the reverse is true.

Hilary Greaves: So, you should either positively or negatively discount future goods relative to present ones. That’s pretty uncontroversial. What’s controversial is whether you should treat welfare in the future as having different weight from welfare in the present. Moral philosophers are more or less unanimous on the view that you should not discount future welfare, and that’s an important input into the case for long term-ism, because if you think you should discount future welfare at, say, an exponential rate, going forwards in time, then even a very small discount rate is going to dramatically suppress the value of possible future welfare we can get summed across all generations. So, you don’t get the kind of overwhelming importance of the far future picture that you get if you have a zero discount rate on future welfare.

Hilary Greaves: So, that will be one of them. Another salient one would be issues in population ethics. So, if we’re talking about premature human extinction in particular, you get the case for thinking it’s overwhelmingly important to prevent or reduce the chance of premature human extinction if you’re thinking of lives that are “lost” in the sense that they never happened in the first place because of premature human extinction. In the same way that you think of lives that are lost in the sense of they got cut short, like people dying early. If you think that those two things are basically morally on a par, so very valuable lives that would contain love, and joy, and projects, and all that good stuff, failed to happen that would otherwise have happened, that’s just as bad if people fail to be born as it is if they die prematurely. If you’re in that frame of mind, then you’re very likely to conclude that it’s overwhelmingly important we prevent premature human extinction, just because of how long the future could be if we don’t get prematurely extinct.

Hilary Greaves: Whereas if you think there’s a morally important sense in which a life that never starts in the first place is not a loss, if you think this is like a victimless situation … because premature human extinction in fact happens, let’s say, this person never gets born, so this person doesn’t exist. So, there in fact is no person we’re talking about here. There is no person who experiences this loss. If you’re in that kind of frame of mind, then you’re likely to conclude that it doesn’t really matter, or it doesn’t matter anything like as much whether we prevent premature extinction or not.

Hilary Greaves: So, those would be two examples of cases where there’s something that’s controversial than moral philosophy that’s gonna have a big impact on what you think about the truth of long term-ism versus not.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. I guess a third argument that I hear made, maybe even more than those two these days, is the question of whether the future’s going to be good on balance. So, is it worth preserving the future, or is it just very unclear whether it’s going to be positive or negative morally, even taking account the welfare of future people? But maybe that’s less of a philosophical issue, it’s more of a practical issue, so not so much under the purview of GPI.

Hilary Greaves: I think it is under the purview of GPI. I mean, it’s an issue that has both philosophical and practical components, and the philosophical components of it would be under the purview of GPI. So, part of the input into that third discussion is going to be, “Well, what exactly is it that’s valuable anyway? What does it take for a life to count as good on balance versus bad on balance?” So, there are some views, for example, that think you can never be in a better situation than never having been born, because the best possible thing is to have none of your preferences frustrated.

Hilary Greaves: Well, if you’re never born, so you never have any preferences, then in particular you never have any frustrated preferences, so you get full marks.

Robert Wiblin: It’s the ideal life.

Hilary Greaves: If you are born, some of the things you wanted are not gonna happen. So, you’re always gonna have negative marks. There are those kind of views out there and they’re obviously going to be unsympathetic to the claim that preventing human extinction is a good thing. And they tend to be, like that one in my opinion, they tend to be pretty wacky views as a matter of philosophy. But there’s definitely a project there of kind of going through and seeing whether there’s any plausible philosophical view that would be likely to generate the negative value claim in practice.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. Okay. I’m a bit weary of diving into the discount rate issue, ’cause we’ve talked about that before with Toby Ord on the show, and it seems like philosophers just kind of, sing with one voice on this topic. My background is in economics and I feel it’s just like economists are getting confused about this, they’re confusing an instrumental tool that they’ve started putting into their formulas with some fundamental moral issue, in as much as economists even disagree with not having a more pure time discount rate.

Robert Wiblin: My impression, at least from my vantage point, is that economists are coming around to this, because this issue’s been raised enough and they’re progressively getting persuaded. Is that your perception, or …

Hilary Greaves: To some extent. I think the more foundationally minded economists tend to broadly agree with the moral philosophers on this. So for example, Christian Gollier has recently written a magisterial book on discounting, and he basically repeats the line that has been repeated by both moral philosophers and historically eminent economists such as Ramsey, Harrod, and so forth, of “Yeah, there’s really just no discussion to be had here. Technically, this thing should be zero.”

Hilary Greaves: I think there is still some interesting discussions one could have like, for example, I think the concerns about excessive sacrifice are worth discussing. So this is the worry that, if you really take seriously the proposition that the discount rate for future welfare should be zero, then what’s going to follow from that is that you should give basically all of your assets to the future. You should end up with what’s an intuitively absurdly high ratio of investment to consumption. Something needs to be said about that, and I think there are things that can be said about that. But a lot of them usually aren’t said.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. I’m interested to hear what you have to say about that.

Hilary Greaves: It is a discussion that I think could do with more having than it normally gets. Philosophers tend to think about the discounting question in terms of what’s the right theory of the good, as philosophers would say. That is, if you’re just trying to order possible worlds in terms of better from a completely impartial perspective, then what’s the mathematical formula that represents the morally correct betterness ordering. That’s one question in the vicinity that you might be asking.

Hilary Greaves: A subtly different question you might be asking is, if you are a morally decent person, meaning you conform to all the requirements of morality but you’re not completely impartially motivated, then what are the constraints on what’s the permissible preference ordering for you to have over acts? So, it’s much more plausible to argue that you could use a formula that has a non-zero discount rate for future welfare if you’re doing the second thing – that’s much more plausible than thinking that you could have a non-zero discount rate for future welfare if you’re doing the betterness thing.

Hilary Greaves: Actually, I beg the question, because I said you’d be thinking of betterness in terms of completely impartial value, and that closes the question, but remove the word impartial and just talk about sort of betterness overall, then it remains I think substantively implausible that you can have a non-zero discount rate for future welfare. But even if you’re asking that second question, the one about what’s a rationally permitted preference ordering over acts, not just rationally permitted, but taking into account morality, then I think there are more subtle arguments you can make for why the right response to the excessive sacrifice argument is not to have something that looks like a formula for value but incorporates discounting future well being. It’s rather to have something that’s more like a conjunction of a completely impartial value function with some constraints on how much morality can require from you, whether those constraints are not themselves baked into the value function.

Robert Wiblin: I guess I’ve never found these arguments from demandingness terribly persuasive philosophically, because I just don’t know what reason we have to think that the true, a correct moral theory or a correct moral approach would not be very demanding. It seems if anything, it would be suspicious if we found that the moral theory that we thought was right just happened to correspond with our intuitive evolved sense of how demanding morality ought to be. Do you have anything to say about that?

Hilary Greaves: Yeah. I’m broadly sympathetic to the perspective you’re taking here, maybe unsurprisingly, but trying to play devil’s advocate a little bit. I think what the economists or the people who are concerned about the excessive sacrifice argument are likely to say here is like, “Well, in so far as you’re right about morality being this extremely demanding thing, it looks like we’re going to have reason to talk about a second thing as well, which is maybe like watered down morality or pseudo morality, and that the second thing is going to be something like-”

Robert Wiblin: What we’re actually going to ask of people.