Review of progress May 2015

NOTE: This piece is now out of date. More current information on our plans and impact can be found on our Evaluations page.

In this post, which is part of our annual review, we review our achievements, challenges and mistakes over the year ending May 2015.

Table of Contents

Key achievements

Our major achievements this year include the following:

- We made major improvements to our online guide, leading to 400% growth in the monthly rate of significant plan changes.

- Our President, Will, wrote a book, which was released last week.

- We quickly met our fundraising stretch target.

- We were also admitted to the world’s top startup accelerator, Y Combinator.

- We did all this with a smaller budget than last year and despite two staff suffering from long-term illness.

Improvements to our online guide

At the start of 2014, our website had little more than a blog – we had just a one page summary of our advice. By April 2015, we had a twenty page online guide with four sections and 16 career profiles.

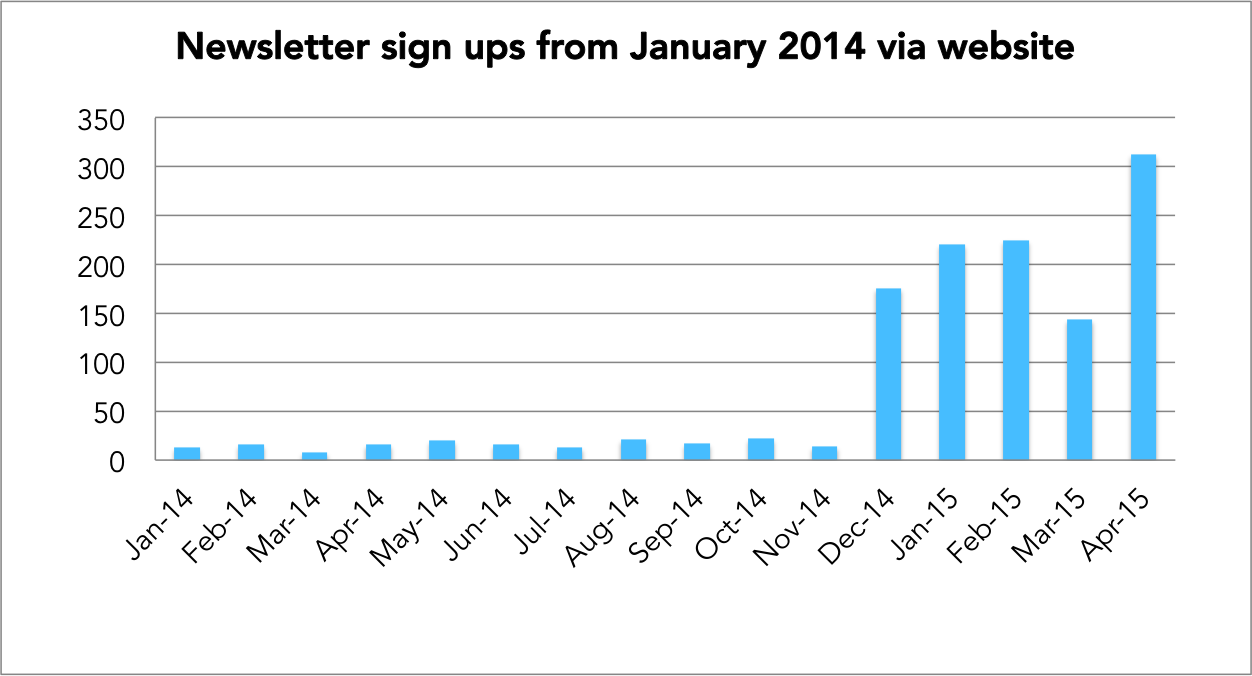

Following the launch of the new content in September 2014, unique page views of the guide reached 46,000 per month by April. Monthly newsletter sign-ups also went up to 313, twenty times the number from the equivalent period last year.

As a result, we estimate that our online content alone is causing six significant plan changes per month, four times the rate in early 2014. (And that’s before taking account of the fact that significant plan changes will lag significantly behind traffic because it takes time to change your career.)

I think we also made significant improvements to the quality of design and writing, as well as many refinements to our core advice.

Creation of Doing Good Better

Having received a large advance in late 2013 on the basis of his book proposal, Will’s main project from April 2014 till January 2015 was writing “Doing Good Better”, a book about how to maximise the social impact of your life. Feedback on the book has been very positive and it has received strong endorsements, including:

Beautifully written and extremely smart. Doing Good Better should be required reading for anyone interested in making the world better.

Steven Levitt, author of Freakonomics

Effective altruism – efforts that actually help people rather than making you feel good or helping you show off – is one of the great new ideas of the 21st century. Doing Good Better is the definitive guide to this exciting new movement.

Steven Pinker, Professor at Harvard University and author of The Better Angels of Our Nature

It was released last week, and has already attracted major media coverage, including Time, Forbes, Fast Company, and Medium.

Strong financial performance

We spent £5,000 less than in 2013, and only used 206 person-weeks compared to 350 in 2013. We used fewer resources because we professionalised the team (fixing the mistake identified in our last annual review). In 2013, we had an average of about three interns, but we reduced this to zero over 2014, and instead added a freelance editor, virtual assistant and web developer. This slowed us down in some ways: we wrote fewer blog posts and did less coaching, which slowed our short-run growth. However it allowed us to make more progress improving our core programs, which is what’s important for long-run growth. Most significantly, in 2013 much of my time was spent on management, whereas in 2014, I was able to spend a significant fraction of time writing the online guide, which interns were not able to do.

I think a small, but able and dedicated team also puts us in a much better position to grow over the coming years. The people we hire today need to grow into leaders in the organisation, and an internship program isn’t the most efficient way to find these people.

In mid-2014, we quickly made our fundraising stretch goals. Combined with the reduced budget, we haven’t needed to actively fundraise again, which also let us make faster progress on our online guide with a smaller team.

Entry into Y Combinator

In May 2015 we were admitted into Y Combinator, widely regarded as the world’s best startup accelerator, whose alumni include Airbnb and Dropbox. YC is a three month program culminating in “Demo Day”, a presentation to top investors in Silicon Valley. The benefits include mentorship from some of the world’s leading experts on startups, a strong credential in the tech community (the selection rate is about 1%), a $100,000 donation, and access to a 1,000-strong network of entrepreneurs.

The program was originally for for-profit technology startups, but two years ago it started accepting nonprofits. We applied as part of the first batch in Winter 2014. We were unsuccessful the first time, but were encouraged to reapply. (Thank you to the many, many people who helped us with our application!)

We wrote our application in March 2015, and prepped for the interview in early May 2015. This process was also very useful for clarifying our strategy and learning about entrepreneurship. We’ll let you know how the program went in our next update.

Improvements to the coaching service

We created a web tool that asks users the questions we found ourselves asking over and over again in our coaching. Combined with a more streamlined workflow, this enabled us to cut coaching time from three hours per person to about one.

We also showed that people are willing to pay for our one-on-one advice. We experimented with a variety of fees, finding that with no promotion at all, we could easily get over one application per day at a price of $60. This strongly suggests that it’s possible for the coaching to cover its own costs.

Improvements to the team

Will accepted an Associate Professorship at Oxford University, making him the youngest tenured philosophy professor at Oxford and probably one of the youngest in the world. Having this title will be a major help with outreach.

We hired Peter Hartree full-time to the team in February 2015 after starting freelance in June 2014 – he’s responsible for much of our progress on the website and coaching process.

CEA’s central team, which provides us with operations and fundraising support, also had a strong year, and we hardly had to spend any time on operational issues. In early 2015 the team also hired a great new head of operations, Tara MacAulay.

Our impact and cost-effectiveness

We recorded 81 new significant plan changes, raising the total since we began from 107 to 188 as of the end of April 2015. This is mostly attributable to our online content.

The ratio of historical costs to significant plan changes decreased from about £4,000 at the end of 2013, to under £2,000 as of now.

At the same time, our estimates of the value of a plan change have increased. We looked at the average additional amount plan changers expect to donate within the next three years due to our influence: it increased 470% from £6,500 at the end of 2013, to £37,000 as of now.

Moreover, we now count five professional nonprofits founded, which likely wouldn’t exist without 80,000 Hours, and collectively have a larger budget than our own. Most notably, the Global Priorities Project was founded over the last year; it’s a non-partisan think tank that undertakes cause priorities research, and has already advised top levels of the UK government.

Some impressive example of plan changes we discovered this year include:

- Hauke Hillebrandt, who was hired by Giving What We Can;

- Tyler Alterman, who co-founded EA Ventures and is running EA Global;

- Ben Gilbert, who is working with Matt Gibb’s startup; and

- Ben West, who quit his job as a programmer to found a health tech company which has already raised $1m of funding (and he’s pledged to donate all of his income over minimum wage).

See more detail on our metrics and cost-effectiveness in the review of program performance.

What challenges did we face?

Our greatest challenge was hiring. We set out to hire a researcher, but despite trialing several people we didn’t find any candidates who were a good enough fit and able to start in 2014. We also came close to adding two other people to the team, but decided against doing so.

The main problem is that we’ve been trying to make a “founder level” hire. That is, someone able to act as an independent leader in the organisation, rather than carry out tasks that are already well defined. This is always extremely difficult, because they need to be highly trusted and fit very well with the team. It’s very difficult to hire someone like this unless you’ve worked with them before.

The research position is also especially difficult to fill since few people have the right combination of skill at reasoning, knowledge of effective altruism and popular writing ability.

This challenge slowed us down, but didn’t stop us from making progress. We can achieve a lot with the existing team, and as tasks become more concrete, it’ll become easier to hire new staff.

Another significant challenge was illness. Our head of coaching was on leave for much of the year, so we ended up with much less coaching capacity than we planned. This meant we only coached 28 people by the end of the year, less than our target of 40; however, we exceeded this target in the first quarter of 2015. Will was also struck by chronic back pain, losing months of productivity.

We realised we could use better product design skills. While working on the online guide we came to realise these skills are similarly important to web development skills, but none of us has a background in them. In response, Peter started learning.

How did we perform relative to our goals?

We succeeded in our goals from the last review with a few exceptions I’ll list below. We think these misses are justified by other achievements we made in their place.

We spent more time on writing the online guide and less on original research than planned (e.g. we didn’t make our goal to publish 5 in-depth career profiles). This was in part because we didn’t manage to hire a researcher, but it was also because I realised it would have a higher return for me to improve the write-ups of our existing ideas – this allowed me to produce content several times faster than original research.

We also focused more on the online guide because we were able to hire Peter Hartree, a web developer, allowing us to make much more progress on the website than anticipated.

I think this decision was vindicated by the success of the online guide: we had 46,000 unique pageviews to the career guide pages in April 2015 alone and it’s generating a stream of plan changes.

Similarly, we didn’t do an external research evaluation. This didn’t seem valuable compared to actually writing a compelling explanation of our ideas in the career guide. Moreover, we had little push from donors and other stakeholders – people judge the quality of our research simply by reading it themselves and seeing whether it causes plan changes. However, we would still like to set ourselves up to get better feedback on our work, and will be thinking about how to do so over the next year.

Our mistakes

Mistakes concerning our research and ideas

We let ourselves become too closely associated with earning to give.

This became especially obvious in August 2014 when we attended Effective Altruism Global in San Francisco, and found that many of the attendees – supposedly the people who know us best – saw us primarily as the people who advocate for earning to give. We’ve always believed, however, that earning to give is just one strategy among many, and think that a minority of people should pursue it. The cost is that we’ve put off people who would have been interested in us otherwise.

It was hard to avoid being tightly associated with earning to give, because it was our most memorable idea and the press loved to focus on it. However, we think there’s a lot we could have done to make it clearer that earning to give isn’t the only thing we care about. Read more.

We presented an overly simple view of replaceability, and didn’t correct common misconceptions about it

We think many of our previous applications of the replaceability argument were correct, but we don’t think it means that you shouldn’t take jobs with direct impact (e.g. working at a nonprofit) or that it’s okay to take harmful jobs for indirect benefits.

Unfortunately some of our early content suggested this might be the case, and we didn’t vigorously correct the misconception once it got out (although we never made replaceability a significant part of our career guide). We’re concerned that we may have encouraged some people to turn down jobs at high-impact organisations when it would have been better to accept them. Read more.

Not emphasising the importance of personal fit enough

We always thought personal fit – how likely you are to excel in a job – was important, but (i) over the last few years we’ve come to appreciate that it’s more important than we originally thought (most significantly due to conversations with Holden Karnofsky) and (ii) because we didn’t talk about it very often, we may have given the impression we thought it was less important than we in fact did. We’ve now made it a major part of our framework and career profiles.

Released an interview about multi-level marketing

We asked users to send us interviews about careers they knew about. One sent us a favourable interview about multi-level marketing, which we released. We were quickly told by a reader that multi-level marketing is highly ethically dubious, and took the post down within an hour. We should have better vetted user-submitted content before release.

Operational mistakes

Allowing a coaching backlog to build up in late 2014

We allowed a large backlog of over 100 coaching applicants to build up at the end of 2014, with the result that many had to wait several months for a response. This happened because our head of coaching was repeatedly on sick leave over the last half of 2014, and I didn’t step in quickly enough to close applications. To make it right, we apologised to everyone and gave email advice to about 50 of the applicants. When we set up our new coaching process in early 2015, we closely monitored the number of applicants and response times, closing applications when our capacity became stretched.

Not improving the online guide earlier

In September 2013 we took down our old career guide, going for a year without a summary of our key advice outside of the blog. I was aware of the problems this caused – most readers don’t visit useful old posts, and it was hard to find our most up-to-date views on a topic. I could have made a minimal replacement (e.g. a page listing our key articles) back in September 2013, which would have resulted in thousands of extra views to our best old content. Instead, we focused on coaching and new research, but in retrospect I think that was lower priority.

We should also have added a newsletter pop-up earlier. We were wary of annoying readers, but it dramatically increased our conversion rate from 0.2% to over 1%. In the end, we added a more complex appeal that just slides down under the header rather than popping up, and is only shown to engaged readers, with the aim of making it less annoying. However, we could easily have added a simpler pop-up a year ago, which would have resulted in 1000-2000 extra newsletter subscribers.

Simultaneously splitting our focus between the online guide and coaching

Perhaps an underlying cause of the previous two mistakes was that we attempted to push forward with both coaching and improving the online guide at the same time, despite only having the equivalent of two full-time staff working on them. We did this despite knowing the importance of being highly focused.

With more focus, we could have had clearer and shorter development cycles, better metrics, and generally better management, which would have helped the team to be more productive.

The reason we didn’t focus more was that we were reluctant to close the coaching, even temporarily, but in hindsight this wasn’t a strong consideration compared to the benefits of focus.

Not focusing more on hiring people we’ve already worked with

It’s widely seen as best practice in startups for the first couple of team members to be people who have worked together before and can work together really closely. We were aware of this advice but pushed forward with trying to hire new people. This mostly didn’t work out, costing significant time and straining relationships.

I think it would have been better either not to hire, or to focus on doing short, intense, in-person trials, since that’s the best way to test fit quickly. Instead, we did longer but less intense trials that were often remote and spread out over the year.

More detail on our performance

See an in-depth review of our metrics, costs and the performance of our programs.