Does your personality matter in picking a career?

Introduction

In order to work out best practice within career advising, we looked into personality testing. Several people we’ve asked for advice have recommended that we consider using it.

Having investigated the leading personality tests, however, we’ve concluded they’re not very useful in choosing your career. This is because they haven’t been shown to predict the real world outcomes that matter: (i) finding careers you will find satisfying (ii) finding careers that you will succeed in.

Key takeaways: given our findings, what do we recommend?

- Personality tests have not yet shown to be directly useful in picking which careers will fit you, so don’t put much weight on them

- Be more sceptical about claims about which career might suit you based on personality

- To judge your chances of success, put more weight on IQ, grit and experience.

- When looking for job satisfaction, put more weight on the nature of the work and the quality of the social support in the workplace you’re considering

- Do plenty of trial and error. There’s a lot we can’t yet predict and don’t know. If you’re wondering whether a job will suit you, the best way to find out is to try it.

Our findings on personality testing

The most widely used personality test in the world is the Myers Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI). There are plenty of reasons to doubt that this test is a good measure of personality. More importantly, there has been very little testing (and nothing within the academic community) of the predictive power of the test.

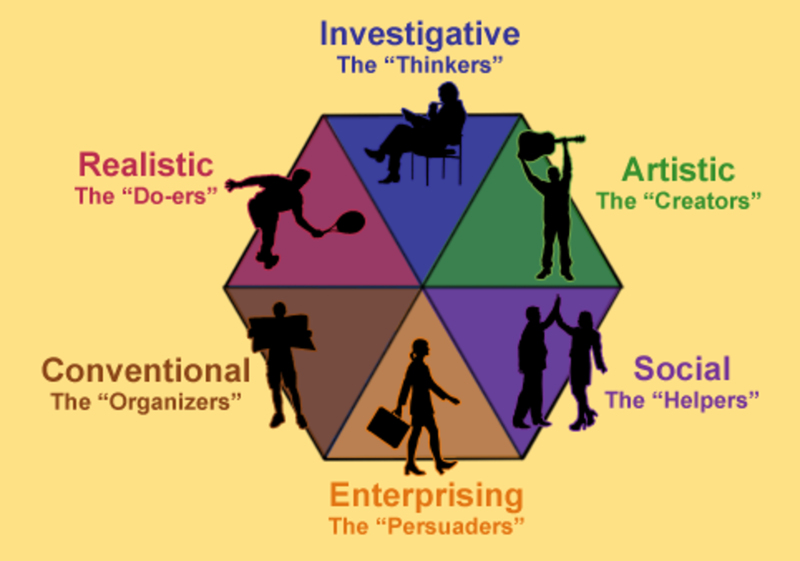

Holland Career Types

The most well-tested and popular personality test developed specifically for career choice is the Holland Type Test. The academic community has attempted to show that a matching between the Holland type of a person and their workplace is predictive of job satisfaction. To date, meta-studies have shown no correlation or only a very weak correlation. There’s a good chance this is partly due to some confounding factors and more work needs to be done, but the balance of the evidence now it that Holland type matching is only weakly predictive.

The most widely used personality measure among academic psychologists is the Big 5. This measure does at least have some predictive power in career outcomes. The strongest and most widely agreed finding is that conscientiousness predicts job performance, across a very wide variety of professions.1 Turn to the size of the effect, however, and you’ll discover it’s tiny. Typically, conscientiousness only explains several percent of the variance in performance. My impression is that it’s similar for the other well-established predictions based on personality.

What does this mean? Either:

1. Personality is important, but it’s difficult to demonstrate because the interactions are so complex. Further research will show stronger effects.

2. Personality is less important in picking a career than we think.

I think both of these explanations are likely true to some extent. The existing research is pretty crude. For instance, it might be that the personality of your immediate colleagues is very important, but not the personality type of the people who do the work in general. It’s also difficult to design studies that show the full correlation, due to range restriction effects and others. But overall I lean slightly towards (2) being true.

We’ve found other factors that do make a big difference in picking a career. In predicting performance, intelligence, as measured by IQ, seems to be very important across a very wide range of careers. Often, it explains 30-60% of the variance, meaning that it dwarfs conscientiousness.

An emerging line of research suggests that grit – the propensity to stick to your goals over long periods of time – matters more than conscientiousness. One recent paper2 showed that grit could explain 5% of the variance in performance across six different areas, compared to only 2% for conscientiousness. (Though note that IQ was still found to be a much better predictor of performance than grit). Grit is partly is measure of personality, but it’s also partly based on your mindset, which is a product of your beliefs not your personality. Another line of research, for instance as explored in a pop form by Carol Dweck in the book “Mindset”, suggests that certain beliefs about the world can also impact your success, though we’re not yet sure how much.

What could explains the rest of the variance besides personality? We don’t know. Experience can matter. In particular, there’s a fairly strong line of research3 showing that thousands of hours of deliberate practice are necessary for expert performance in a wide variety of fields. Some genetic factors have been linked to success, like physical attractiveness and height. A big chunk is likely down to luck. We’d like to explore these factors in the future.

What about finding a satisfying job? We’ve found that the nature of the work itself is the most important thing. After that, what’s important is whether the social environment at work is generally supportive (which doesn’t depend on personality matching).

All in all, there is plenty of room for these other factors to dominate the role of personality in career decisions.

Why is there so much focus on personality in career choice then? And why do personality tests continue to be so popular? We suspect it’s because the message that certain types of personality suit certain types of job is a nice one. Many of these other factors are much less encouraging. If the nature of the work is what’s important in job satisfaction, then that means that on average some jobs are more satisfying than others. And you can’t change your IQ or height. The message of the other factors is that you need to change your beliefs about the world and do a ton of work to succeed. That’s also not an easy line to take in a brief careers advising session.

You might also be interested in:

- Our research on finding a job you’ll love

- Does fitting in a work matter?

- Intelligence matters more than you think

- Reasons to be suspicious of Myers Briggs

Notes and References

- See a summary of the literature in “Select on Conscientiousness and Emotional Stability” ( MURRAY R. BARRICK AND MICHAEL K. MOUNT ), Chapter 2, E. Locke, Handbook of Principles of Organisational Behaviour ↩

- “Grit: Perseverance and Passion for Long Term Goals”, Angela L. Duckworth, Christopher Peterson, Michael D. Matthews and Dennis R. Kelly

http://www.sas.upenn.edu/~duckwort/images/Grit%20JPSP.pdf ↩ - See a summary in this article: “Expert Performance,” Ericsson and Charness, 1994, American Psychologist

http://stuff.mit.edu/afs/athena.mit.edu/course/6/6.055/readings/ericsson-charness-am-psychologist.pdf ↩