Should you play to your comparative advantage when choosing your career?

“Do the job that’s your comparative advantage” might sound like obvious advice, but it turns out to be more complicated.

In this article, we sketch a naive application of comparative advantage to choosing between two career options, and show that it doesn’t apply. Then we give a more complex example where comparative advantage comes back into play, and show how it’s different from “personal fit”.

In brief, we think comparative advantage matters when you’re closely coordinating with a community to fill a limited number of positions, like we are in the effective altruism community. Otherwise, it’s better to do whatever seems highest-impact at the margin.

In the final section, we give some thoughts on how to assess your comparative advantage, and some mistakes people might be making in the effective altruism community.

The following are some research notes on our current thoughts, which we’re publishing for feedback. We’re pretty uncertain about many of the findings, and even how to best define the terms, and could easily see ourselves changing our minds if we did more research.

Reading time: 10 minutes

Table of Contents

- 1 When does comparative advantage matter?

- 2 Is comparative advantage important in the effective altruism community (and other communities)?

- 3 As an individual in a community, how should you factor comparative advantage into your decisions?

- 4 Potential comparative advantage mistakes in the effective altruism community

- 5 Conclusion and summary

- 6 Read next

- 7 Appendix

When does comparative advantage matter?

A simple example where it doesn’t

Here’s a case where you might think comparative advantage applies, but it actually doesn’t. (We’ll define terms more carefully in the next section.)

Imagine there are two types of role, research and outreach. There are also two people, Carlie and Dave, who are considering which role to take.

Carlie would have 2 units of impact as a researcher and 7 units working in outreach. Dave would create 1 and 4.

What should they do?

| Person | Research | Outreach |

|---|---|---|

| Carlie | 2 | 7 |

| Dave | 1 | 4 |

Both Carlie and Dave should work in outreach, since 7+4 is the highest achievable amount of impact.

So, in this situation, there is no need to worry about comparative advantage. Instead, Carlie and Dave should simply do the role they’d have the most impact in at the margin. Carlie has more impact in outreach than research, so she should do that; and Dave also has more impact in outreach than research, so he should do that too.

When comparative advantage becomes important: diminishing returns (and definitions of key terms)

Now let’s add a complication:

Diminishing returns: each additional worker is less valuable than the preceding one.

Diminishing returns are common in real situations, because people generally take the most valuable options first. For instance, a research group might need one person to specialize in each area of expertise they need – one economist, one biologist, one psychologist etc. If they can only afford to hire three people, they’ll pick one from each. Funding more researchers beyond that will be less valuable, and so has diminishing returns.

A simple way to add diminishing returns to the example above is to suppose that we only need one person doing research, and one person doing outreach. Then the value produced by the second person in any role drops to zero.

As a result, Carlie and Dave will choose to coordinate to avoid both doing the same job, with one person producing zero value. So if Carlie does research, Dave will do outreach, and vice versa.

Then, which job should they each take?

There are two possibilities: either Carlie does outreach and Dave does research, or vice versa.

The best option is that Carlie does outreach and Dave does research. That’s because 1 + 7 = 8, which is greater than 2 + 4 = 6.

What’s odd about this?

Dave should do research, even though he’s both “worse” at research than outreach (1 unit of impact vs. 4), and worse at research than Carlie (1 unit of impact vs. 2).

Let’s define Dave’s single-player advantage as:

Single-player advantage: the job in which you’d have the greatest impact ignoring the possibility of coordination.

Dave’s single-player advantage is in outreach, but it’s higher impact for him to do research. In this case, we say that Dave has a comparative advantage in research:

Comparative advantage: the job that’s highest-impact taking account of the possibility of coordination.

This is because he’s relatively less bad at research compared to outreach than Carlie. If Carlie were to do research, she’d give up 5 units of impact, while Dave will only give up 3.

We call this a “comparative advantage situation”, which we define as follows:

Comparative advantage situation: a case when the job that’s your comparative advantage differs from your single-player advantage.

Dave should also do research even though he has worse personal fit with research, as well as single-player advantage. Let’s make one final definition:

Personal fit: How productive you’d be in the job in the long-term relative to the average productivity of other people who are likely to take the job.

Compared to Carlie on research, Dave is ½ = 50% as productive, while he’s 4/7 = 57% as productive in outreach. So, Dave has better personal fit in outreach, but it’s higher-impact to do research.

Single-player advantage will roughly equal role impact multiplied by personal fit i.e. the product of how high-impact the role is in general (at the margin) and how productive you are in the role compared to others in the role. This means that comparative advantage situations will tend to be those in which you should do an option with worse personal fit in order to have a greater impact, but it also depends on the impact of the role and personal fit of other available people.

In this example, we’ve introduced diminishing returns in a very simple way, but you can get similar examples using a more complex model, as we show in the appendix.

One issue we’re not sure about is that in large populations, diminishing returns will be relatively small at the margin. This could mean comparative advantage is less important when considering large populations, and relatively more important when considering small groups and teams.

Another way comparative advantage becomes important: complementarity

In many situations, you need multiple inputs working together to create an impact. For instance, if you have a lot of people putting on events but no-one doing marketing, then no-one would attend the events, so they’ll never have any impact. Or if you only have people doing marketing, then you don’t have any events, so the marketing isn’t valuable. This means that you need to add event organisers and marketers in the right ratio, and the two roles are complementary.

More technically, the better your events the more valuable it becomes to have them well marketed; and the better your marketing, the more important it is that your events are good.

Complementarity can also create comparative advantage situations, even if you don’t have diminishing returns. (We explore this in more depth in the appendix, even showing you can get comparative advantage with increasing rather than decreasing returns.)

Here’s a simplified example with complementarity: the decision between direct work and earning to give.

Suppose Carlie and Dave represent two types of people that could work in a community, and there are 30 Carlies and 30 Daves. Each can either do direct work, or they can earn to give and fund people to do direct work. Each direct worker costs $2.

| Type of person | Value produced in direct work | Money donated earning to give |

|---|---|---|

| Carlie | 3 | $4 |

| Dave | 1 | $2 |

How should roles ideally be allocated?

One option is that all 30 Daves earn to give, earning $60. This can then be used to pay for all the Carlies to do direct work, producing 90 units of value.

Another option is that 20 Carlies earn to give, earning $80. This is enough to pay for the other 40 people (10 Carlies and 30 Daves) to do direct work, producing 60 units of value.

So, the first scenario is better.

In the first scenario, the Daves all earn to give, even though they’re “worse” than Carlies at earning to give, because they only have $2 of earning potential compared to $4 (i.e. they have lower single-player advantage). But this leads to more impact overall because it frees up the Carlies to do direct work, who can have even more impact. So it’s a comparative advantage situation.

Is comparative advantage important in the effective altruism community (and other communities)?

There are at least three factors that determine how important it is to consider comparative advantage in addition to personal fit.

1. Are there diminishing returns or complementarity?

We’ve seen that comparative advantage becomes important when a group has different skill sets, needs to fill several types of roles, and where the roles are either complementary, or have diminishing value.

We expect this to be the case in most communities much of the time, including the effective altruism community. For instance:

- The effective altruism community needs enough funders to fund all the talented direct workers to work in nonprofits. So, we need the right ratio of each, which means funders and direct workers are complementary. Over the long-term, we’d also expect diminishing returns in both funding and talent, because we’ll take the best opportunities to do good first.

- Within direct work, each nonprofit needs someone to cover each major skill set – outreach, operations, tech, research, management, and so on. So, as a community, we need the right balance of people with each skill set, which is complementarity.

- The community also needs the right expertise and connections: we need to know about all the major problems in the world, and the most promising avenues for solving them, such as policy, direct work, advocacy and research. This means it’s valuable to have a couple of people within each major area of expertise, who can advise everyone else, as well as act as a bridge to other communities. So, these experts are complementary with generalists. However, you can get a large portion of the value from just a couple of people in each area, so you also have diminishing returns.

In these examples, the ideal allocation for the community is one in which people allocate across these roles depending on their comparative advantage compared to others in the community.

2. Are people responsive to your choices?

In the examples earlier, we assumed that both Carlie and Dave were aware of what the other person was doing and its impact. This meant that if Carlie did one thing, Dave would do the other, and vice versa.

If they’re not able to respond to each other’s choices, then comparative advantage might stop mattering. For instance, let’s go back to the diminishing returns example. Carlie and Dave can allocate in the following ways, and there is only room for one extra researcher and one extra person doing outreach.

| Person | Research | Outreach |

|---|---|---|

| Carlie | 2 | 7 |

| Dave | 1 | 4 |

The ideal allocation was Carlie doing outreach and Dave doing research, which produced 7 + 1 = 8 units of impact.

Now suppose that Dave will do outreach whatever happens (ignoring his comparative advantage). Now, Carlie has the choice to either do outreach, and have zero impact, or to do research and have 2 units of impact. Clearly, it’s now better for her to do research.

Comparative advantage is only important when the community is, to some degree, responsive to your choices. In markets, this happens through prices – if it’s Britain’s comparative advantage compared to Portugal to produce cloth rather than wine, then it’ll be more profitable to sell cloth to Portugal in exchange for wine. However, in the world of doing good (at least now), we can’t rely on price mechanisms, so coordination has to be done in other ways.

What determines the responsiveness of the community? These seem like several key factors:

- How well does information about what’s needed spread through the community? If people aren’t aware of what’s highest-impact, then they can’t act on it. Information can spread through word-of-mouth, surveys, decisions by hiring managers, and so on.

- To what extent will people act on this information? For instance, if community members are more focused on personal satisfaction, then they won’t adapt to your choices.

- How much do people agree about what’s best? If people radically disagree about what’s best, then again, they’ll probably ignore what you do.

Overall, we think the community is at least somewhat responsive to what everyone else is doing, so comparative advantage matters to some degree. Often it might not seem like the community is responsive in the short-term, but eventually word gets out about which roles are most needed, and at least some people are willing to plug the gaps.

We discuss some practical ways to gauge your comparative advantage and coordinate in real situations in the next section.

3. Are the skills in the community unusually distributed compared to its needs?

If everyone in the community had exactly the same skills, then comparative advantage situations seem less likely to arise.1 This is because one way they can arise is when differences in skills create the possibility of trade within the community.

We expect that the more extreme the dispersion of skills, the more important it becomes to consider comparative advantage.

Similarly, if a community needs 50% researchers and 50% operations staff, and exactly half of its membership have great personal fit with research and half have great personal fit with operations, then the ideal allocation is simple: everyone just does the option with the best personal fit and single-player advantage.

However, if the community contained 70% people with good personal fit with research and 30% with operations, then it might be the case that some of the “excess” 20% who are best suited to research should instead do operations, and we’d have a comparative advantage situation.

So, another factor is how well the skills available in the community matches the needs of the community.

The effective altruism community seems to have a very unusual distribution of needs (e.g. we need lots of people with an interest in existential risk) and an unusual distribution of skills (e.g. it contains far more philosophers than the population), so we should expect comparative advantage situations to arise.

Summing up: when are comparative advantage situations most likely to arise within a community?

We’ve covered the following pathways:

- There are significant diminishing returns and/or complementarity between roles in the community.

- The community is responsive to your choices.

- The skills in the community are widely distributed and poorly matched with its needs.

All of these seem to apply to the effective altruism community, so we should expect it’s worth giving some weight to comparative advantage.

As an individual in a community, how should you factor comparative advantage into your decisions?

Start with your single-player advantage

In many situations, your comparative advantage will correspond to the role that has the best single-player advantage, which depends on role impact and personal fit. They’re more likely to come apart when the three conditions in the previous section are met. This means that in many situations, you don’t need to consider comparative advantage separately.

What’s more, as we’ll show, it’s relatively difficult to gauge your comparative advantage compared to your personal fit. This is because to gauge personal fit relative to a field, you only need to know where your skill falls relative to others in the field. However, to gauge comparative advantage, you also need to know the level of personal fit of other community members with all of your options, creating a huge number of possibilities.

This suggests that when trying to work out the highest-impact role in a community, take your ranking of roles by single-player advantage as a starting point, then, if it’s possible to gain information about your comparative advantage, factor that into your ranking depending on the strength of the evidence.

Now, we’ll cover some ways to gain evidence about your comparative advantage.

The big picture: taking a portfolio approach

If we had an efficient market for impact, in which everyone was financially compensated in line with the social value of their contribution, then you could simply take the job that paid the most, and you wouldn’t need to make your own estimates of comparative advantage. However, we don’t (yet) have such a market on a significant scale and are not sure how well it would work. So, for the meantime, we have to make the best guesses we can.

The ideal approach would involving considering all the high-impact roles and all the available people, and then optimally matching the two using comparative advantage.

However, this is not practically possible for several reasons:

- It’s really hard to know what the ideal allocation would be.

- Even if we did, not everyone is prepared to change.

- And we might be so far away from the ideal allocation, that individuals should do something different than what they’d do if everyone else were acting optimally.

Instead, we need to look for more practical rules of thumb for deciding which roles to do, in more constrained contexts. In what follows, we’ll give ideas for simpler rules of thumb, and show that they still lead to a different picture of which actions are best than if we had ignored coordination.

Several approaches to assessing your comparative advantage

Two roles and two people

We may not be able to apply comparative advantage in the fully general case considering all roles and all people in the community, however, we can still apply it in constrained situations, and achieve a slightly better allocation at the margin.

It’s easiest to assess your comparative advantage when there are two people comparing the same two roles, who both know each other.

For instance, in the early days of 80,000 Hours, both Benjamin Todd (the primary author of this article) and someone called Matt were considering becoming CEO of 80,000 Hours or earning to give to fund 80,000 Hours (and other startups in the community). This looks like a comparative advantage case, because we have (i) diminishing returns – we only need one CEO, and (ii) complementarity – it’s better to have one CEO with plenty of funding; rather than two nonprofit workers without much funding, or two people earning to give with fewer good places to donate.

So, we did a side-by-side comparison. We figured that Benjamin would be better at running 80,000 Hours than Matt, but had lower earning potential relative to him. So, that made it relatively clear: the ideal allocation was Benjamin as CEO and Matt earning to give. This was true even though Benjamin might have had a single-player advantage in earning to give. (This, of course, wasn’t the only factor in our decisions — we also wanted jobs we enjoyed with good career capital — but comparative advantage was one factor.)

We’ve seen other cases like this within 80,000 Hours. For instance, right now we need both researchers and coaches. These roles are complementary – the researchers help to attract people to coaching and also ensure our coaches have good advice; but written content alone is usually not enough to cause someone to change their career. So, within the team, we allocate people between research and coaching depending on their comparative advantage.

If you find yourself in a situation like this, then you can just make a direct comparison of the two scenarios, and work out which is higher impact.

Comparing yourself to other people applying to the same jobs

Most real situations are more complex. For instance, even if we stick to only two roles, often there are three people involved:

- If person A takes job 1, then person B will take job 2.

- But if person A takes job 2, then person C will take job 1.

And often you don’t know exactly who these people are. This makes it much harder to know your comparative advantage. However, it still seems like you can get some relevant evidence.

Let’s suppose you’re wondering whether to do direct work or earn to give. If you speak to people in charge of hiring, and they tell you that your earning potential is much higher than other people considering the same direct work jobs, that’s evidence that you have a comparative advantage in earning to give.

It might even be true that you’re “worse” at earning to give than direct work, when comparing your earning potential compared to others who might take the job, but it could still be better to earn to give if you’re even worse at direct work than the other people who might take similar direct work roles. By earning to give, you could then help to push the community towards the ideal allocation.

What kinds of questions could you ask hiring managers in more detail?

First, ask them:

- How much impact you’d have in the role.

- How much impact their other candidates would have in the role.

One way to get concrete values for these figures is by asking the organisation to choose between two options:

- You work at the organisation.

- You donate $x per year.

The value of x at which the organisation is indifferent gives you a very rough indication of the value of your labour to the organisation measured in donations.

The role looks more promising the greater the difference between your value to the organisation and the value of the next-best person. These estimates capture many of the important considerations, so as a first-pass you should probably take the role where the difference between your value and the value of the next-best person is largest (having adjusted for some organisations being more effective than others per dollar).

But you also need to consider the counterfactual: what would the people who don’t get the job do otherwise?

So second, ask:

- What would the other people considering the role do if they don’t get it?

This helps begin to capture the broader effects of you taking a particular role. For a given role, the better alternatives the other candidates have, the more promising it looks for you to take that role.

Coordination via this pathway already happens to some degree, because hiring managers take account of their effect on other organisations — they don’t want to hire someone who could have had far more impact in another role.

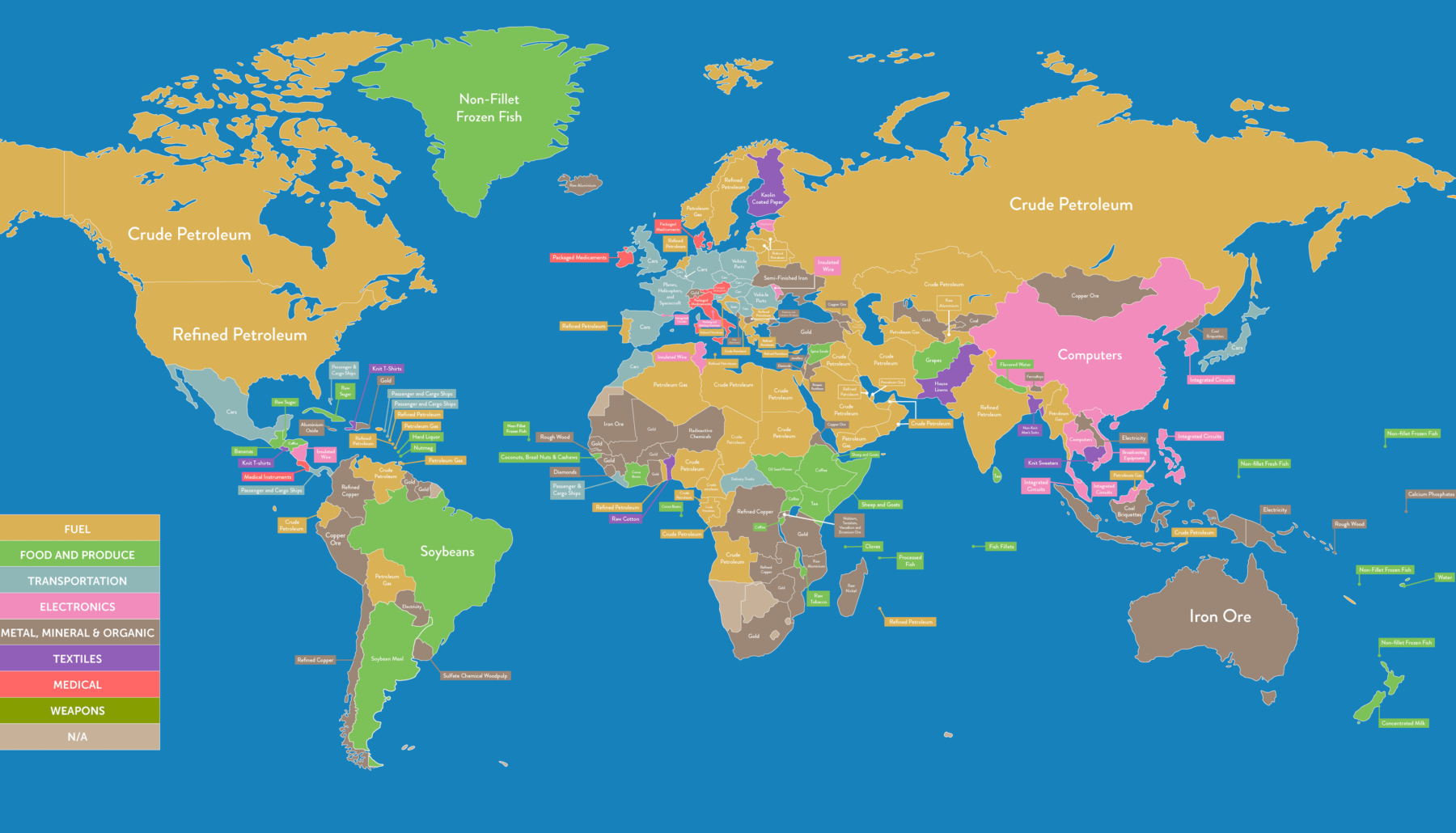

Looking at survey data

As covered, comparative advantage situations arise when the skills needed by the community diverge from the skills people in the community actually have.

This suggests that another useful source of evidence is surveys about the skills of existing community members and the greatest needs in the community. If there’s a skill that’s needed in the community, and you’re good at it compared to others in the community, then that might be a comparative advantage situation.

We do surveys each year about which skills are most needed. If you’d be unusually good at one of the skills most needed by the organisations compared to your other options, that might be your comparative advantage.

It would also be useful to know which skills are most common in the community, because if a skill is more common than in society in general, then it’ll (all else equal) be harder to have a comparative advantage in that skill. For instance, the effective altruism community attracts some of our generation’s most promising philosophers, so although there is a need for more philosophy research, the bar to fill these positions is very high. We give some more examples later.

Unfortunately, we haven’t yet done a survey like this (we’re hoping the 2019 EA survey can include one), so until then you can ask connected people in the community about which skills seem most rare and valuable. Our impression is that skills like software engineering, mathematics, and philosophy are relatively common, while skills in arts and humanities are relatively uncommon. We’re not sure how skills in operations are distributed compared to the population, but they seem to be in short supply relative to the need for them.

Consider the future

In evaluating the above, it’s important to consider the future composition of the community as well as its present composition. If, for instance, the community was going to be flooded with people who are good at operations in five years time, then this would make it less valuable to gain operations skills now.

Most likely, as a community grows, its membership will become more similar to the population in general. This suggests tilting more towards learning skills that you’re good at compared to people in general, and are rare in the general population, such as knowledge of biorisk or moral uncertainty.

Before responding to a skills shortage, you should also think through whether that shortage is likely to persist. For instance, we’ve argued that funding is likely to keep coming to the community faster than aligned talent, which means that the skills involved with running nonprofits are likely to remain in relatively short supply.

In our future talent surveys, we intend to ask people to predict which skills shortages they think are most likely to be around in 5 years as well as those that are faced today.

How to factor in comparative advantage compared to other factors: expanding the career framework

Ordinarily, in our career framework, we propose that the highest-impact long-term role is the one with the best combination of these three factors:

- Role impact potential (effectiveness of area * effectiveness of role)

- Career capital potential

- Personal fit.

We think personal fit multiplies the other two factors.

However, in cases where comparative advantage matters, we need to expand this to:

- Role impact potential

- Career capital potential

- Personal fit

- Relative fit

Your relative fit is how good you’d be at the role compared to other community members. The idea is that the role in which you have the highest comparative advantage is the one with the best combination of role impact and relative fit.

However, personal fit is still important for a couple of reasons.

First, if you have good personal fit with a role, then you’ll gain more impressive achievements and connections, (and therefore career capital) and probably be more satisfied in it, and so more likely to persist.

Second, the community is probably not perfectly responsive to your actions and you probably don’t fully share its aims. As covered earlier, when responsiveness is low, then you need to fall back on the role that has the highest single-player advantage, which corresponds to role impact multiplied by personal fit.

Third, personal fit and comparative advantage are also going to coincide in many cases. They only come apart when the community has an unusual distribution of skills to needs (and you know what these differences are).

Your relative fit is relevant to your career capital too, because from the community’s point of view, it’s better if people build up skills that will be a comparative advantage in the long-term. (Though, if we break out “contribution to community capital” as a separate factor, as we will do in an upcoming article, then it would be contained in there instead.)

All this means that if we had to fit the factors together in a formula, it might look something like the following, though this is very rough:

Long-term impact = (career capital potential + role impact potential) * (personal fit + relative fit).

To apply this framework to a decision like what nonprofit to work out, you’d want to ask:

- How high-impact is the organisation in general?

- How important is your role to the organisation?

- How good will you be at that role compared to others they might hire? (gauged in the way we recommend above)

- How much career capital can you gain from this role?

- How promising are your other options compared to what other potential hires might do?

- Are there other important elements of job satisfaction?

Membership of multiple communities

In practice, you might be part of more than one community, which only partially overlap. For instance, many people work with both the AI safety community and the effective altruism community. In these cases, ideally you’d consider your comparative advantage compared to people in both communities, in proportion to your degree of alignment with them and their responsiveness.

Ultimately, you could think of being surrounded by concentric rings of communities that are less and less coordinated with you, until we reach the whole future economy.

In practice, however, if you consider both personal fit and your comparative advantage with the community that is most important to you, then we expect you’ll capture a significant fraction of what matters.

Potential comparative advantage mistakes in the effective altruism community

Here are three ideas for mistakes concerning comparative advantage we think we sometimes see people make in the community.

Assessing comparative advantage is very personal – it depends on your particular skill set. So although we think the community in general is making the following mistakes, bear in mind that this doesn’t mean that you should necessarily shift your career in the directions we suggest.

Should I earn to give or do direct work?

We often advise people who say: “I have high earning potential, so I have good personal fit with earning to give, so I should earn to give”.

But this doesn’t follow. We’re in a situation where we need the right ratio of funders to direct workers, so what matters is comparative advantage. This means you need to compare your earning potential to other people in the community who might do direct work or earn to give.

If they have even higher earning potential, then you might have a comparative advantage in direct work, even though you have high earning potential compared to people in general.

Cases like this might be common. There are people doing direct work in the community who could donate over $500,000 per year earning to give. So, even if you have earning potential this high, you might still have a comparative advantage in direct work.

Of course, some people’s comparative advantage will be earning to give. If it looks like you might be less good than existing people doing direct work, or you have struggled to find work in direct work, we think that earning to give is a great alternative.

Should I do research or operations?

We also often see people who reason: “I’m pretty analytical, so I should do research rather than operations”.

This might also not follow. There are lots of analytical people in the community, and what matters is how analytical you are compared to them rather than people in general.

In practice, we’ve seen several people who could have done research go into operations instead, and probably have a larger impact there. (Read more in our full article on the need for operations staff.)

On the other hand, the need for researchers in the community is perhaps even greater than operations, so if you have a shot at being a successful researcher, then that’s well worth pursuing. The issue is that the bar for being a “successful” researcher is a bit higher than it first seems.

Ben Kuhn suggests there might be a similar situation with analytical roles compared to outreach roles on his blog.

Should I be a generalist or a specialist?

We’ve encouraged people to gain flexible career capital to keep their options open, and it’s certainly valuable to stay flexible.

However, as we’ve discussed, it’s also valuable for the community to have at least a couple of specialists in each area, because their expertise is complementary with everyone else. If everyone else is trying to be a generalist, then it makes the specialist roles more and more valuable. Eventually, it could become your comparative advantage to be the specialist, even if you have a single-player advantage as a generalist.

This is most likely in cases where you’ve already made a major investment in a relatively uncommon skill set that’s important to the community. For instance, Greg Lewis conducted our research into the direct impact of clinical medicine, and decided that wasn’t the way for him to have the largest impact. So, he wondered what to do instead. Greg has already qualified as a doctor, which is uncommon among other researchers in the community. Connections with the public health community are also important for pressing issues like pandemics, global health, and bioengineering. This made him think that he likely has a comparative advantage in being a biorisk researcher. So, this was a reason in favour of that path (among other important factors).

Which comparison group is most relevant?

Unfortunately, we also worry that people make the opposite mistakes to the above. One way this happens is that it’s easier to compare yourself to your immediate friends rather than the whole community. So if your friends are unusually good at a certain skill, it’s easy to conclude that it’s not your comparative advantage, even though it might still be rare compared to the community in general.

This is why it’s important to try to use surveys rather than gut impressions to assess comparative advantage.

Conclusion and summary

We’ve found it surprisingly complicated to work out how comparative advantage factors into career decisions. Here’s a summary of our current thinking, as we’ve outlined in this article:

- It can sometimes be higher-impact to do a role that has worse single-player advantage (what’s highest-impact ignoring coordination). We call these comparative advantage situations. This also usually involves taking jobs with worse personal fit.

- Comparative advantage situations can arise when people are being shuffled between a limited pool of high-impact roles. There must be either diminishing returns or complementarity, and the community must be partially responsive to your choices, and have mismatch between available skills and needs.

- Comparative advantage is probably important for allocating people among certain types of roles in the effective altruism community.

- When comparative advantage is relevant, you can factor it into your career comparisons alongside the rest of our career framework, but personal fit remains important.

- You can sometimes assess your comparative advantage by making direct comparisons to other people who might take marginal roles, or by talking to hiring managers and using surveys to get a broader sense of where you’re unusually strong compared to other community members.

We think there’s still a lot to learn about comparative advantage, and what rules of thumb to use when coordinating with a community to have an impact. We’re excited to deepen our understanding over the coming years.

Thank you to Max Dalton for making extensive comments on this article and helping with the definitions; as well as Robert Wiblin, Roman Duda and Ben Kuhn.

Read more about coordination within communities and see some discussion here on the EA Forum.

To be notified about our latest research, join the newsletter.

Read next

This article is part of our foundations series. See the full series, or keep reading:

Thinking about your career?

If you’re thinking through how to apply this advice to your own career choices, our team might be able to speak with you one-on-one. We can help you consider your options, make connections with others working on similar issues, and possibly even help you find jobs or funding opportunities.

Appendix

In the article above, we used a very simple production function with diminishing returns – we assumed only one researcher and outreacher were needed, and that each “unit” of research or outreach translated to one “unit” of impact.

| Person | Research | Outreach |

|---|---|---|

| Carlie | 2 | 7 |

| Dave | 1 | 3 |

Instead, different inputs, such as hours spent on research and outreach, usually combine in a more complex way into “social impact”, which is what we ultimately care about. Economists model this with “production functions”. A very simple production function could look something like this:

Value produced = R + O

Where R = “total talent invested in research” and O = “total talent invested in outreach”.

We now interpret the numbers in the table above as the relative talent of Carlie and Dave measured in hours. So, Carlie produces twice as much research as Dave.

Applying the production function means that if both of them work on research, then the total value produced is 1 + 2 = 3 units of impact.

We can now repeat the example with several different types of production function, and show that comparative advantage situations arise in each.

Diminishing returns

Here’s an example of a production function with diminishing returns.

Value produced = sqrt(R) + sqrt(O)

In this function, value produced has diminishing returns in both research and outreach. For instance, if you get twice as much R and O, then you only get 1.4-times as much impact.

If you run the example with this production function, it still works. If Carlie does outreach and Dave does research, then you produce:

sqrt(7) + sqrt(1) = 3.6

Whereas if Dave does outreach and Carlie does research, then you produce:

sqrt(2) + sqrt(3) = 3.1

If both do research, then you get:

sqrt(2+1) + sqrt(0) = 1.73

If both do outreach, then you get:

sqrt(0) + sqrt(7+3) = 3.16

So, more value is produced if Dave does research, even though he’s “worse” at research than outreach, and also worse at research than Carlie. So, it’s a comparative advantage situation.

(Note that now he’s “worse” than Carlie in the sense of producing fewer units of research in the role; whereas before it was in the sense of producing fewer units of impact ignoring what Carlie did.)

Complementarity

To create a production function with complementarity, then you need to multiply the two factors. For instance:

Value produced = R*O

In this case, there are no diminishing returns – having twice as much R results in twice as much impact – but there is complementarity. If you could increase both O and R by 50%, that would mean you’d get 2.25-times as much impact; whereas if you increase R by 100%, you only get 2-times as much impact.

Again, the example still works. If Carlie and Dave both do the same thing, then you get zero value, because if either R or O is zero, then R*O is zero. There are only two non-zero possibilities:

Carlie does outreach and Dave does research, producing:

7*1 = 7

Dave does outreach and Carlie does research, producing:

2*3 = 6

So again, it’s better for Dave to do research even though he’s worse at it.

Both complementarity and diminishing returns

Economists commonly use a production function with both diminishing returns and complementarity, like this:

Value produced = sqrt(R)sqrt(O)

A production function with this form would still generate comparative advantage cases. As before, you need some of both outreach and research or you get zero.

So, then this leaves two non-zero possibilities: Carlie does outreach and Dave does research, producing:

sqrt(7)*sqrt(1) = 2.65

Dave does outreach and Carlie does research, producing:

sqrt(2)*sqrt(3) = 2.45.

Increasing returns

Here’s a production function with increasing rather than decreasing returns:

Value = R^2 + O^2

This has four non-zero possibilities:

Carlie does outreach and Dave does research, producing:

49 + 1 = 50

Dave does outreach and Carlie does research, producing:

4 + 9 = 13

Both do research:

9 + 0 = 9

Both do outreach:

0 + 100 = 100

In this case comparative advantage doesn’t arise, because without complementarity between the inputs both should do the same activity which they are better at in absolute terms – outreach.

However with increasing returns we could generate a situation in which someone who is worse at an activity should change what they work on in order to join forces with someone who is very good at something else, and take advantage of those increasing returns.

Notes and references

- However, it is still possible for them to arise. Consider:

Carlie: research (2) outreach (7)

Dave: research (2) outreach (7)Diminishing returns mean 2nd person in a role produces 0 value.

Both have a single player advantage in outreach. But if they coordinate, then one could do outreach and the other could do research, which would mean one of them produces 2 units of impact instead of 0.↩