Working at effective altruist organisations

Review status

Based on a medium-depth investigation

Table of Contents

- 1 What do we mean by “working at effective altruist organisations”?

- 2 Why is working at an EA organisation high impact?

- 3 How good is the career capital?

- 4 Other positives

- 5 Other downsides

- 6 How to choose between working at EA organisations vs. other options

- 7 How to assess your personal fit

- 8 Which specific jobs to apply to?

- 9 How can you get these jobs?

- 10 Some interviews with people currently working at effective altruist organisations

- 11 Want to work at an effective altruist organisation? We want to help.

80,000 Hours regards itself as an effective altruist organisation and also wrote this profile. Given our potential to be biased, our views should be taken with a grain of salt.

What do we mean by “working at effective altruist organisations”?

Effective altruism (EA) is about using evidence and reason to figure out how to benefit others as much as possible, and taking action on that basis. If you’ve never heard of effective altruism before, read this introduction.

By this path, we mean working at nonprofit organisations whose leaders aim to do the most good on the basis of evidence and reason, and who identify as part of the effective altruism community.1

Why do we treat these organisations as a group? They’re all part of the effective altruism community, they regularly work together, talent flows between them and they often share similar strategies. For instance, they’re unusually willing (compared to other nonprofits) to change which problem areas they work on, and many focus on “meta” efforts to help people do more good with their time and money. This means it’s useful to treat them as a group.

As of 2017, these organisations include:

Promoting effective altruism & global priorities research

- Centre for Effective Altruism (CEA), which includes a community and outreach division that runs Giving What We Can, a fundamentals research team, and 80,000 Hours (yes, that’s us).

- Open Philanthropy and Good Ventures

- Effective Altruism Foundation, which includes the sub-projects Foundational Research Institute and Raising for Effective Giving.

- Founder’s Pledge

- Charity Science

- Rethink Charity (formerly named .impact)

Sometimes people use the term ‘effective altruist organisation’ to refer to just the group above, but we’re using the term in a slightly broader sense to also include the following organisations which are part of the broader community:

Existential risks

- Centre for the Study of Existential Risk at Cambridge University

- Future of Life Institute

- Machine Intelligence Research Institute

- AI Impacts

- Berkeley Existential Risk Initiative

Global health & development

- GiveWell

- The Life You Can Save

- Charity Science: Entrepreneurship and its subproject Charity Science: Health

- EA Australia

Animal welfare

Note that as part of this profile we don’t include:

- Academic research roles at the Future of Humanity Institute and the Centre for the Study of Existential Risk, some of which we cover in a separate profile (but we do include academic project management and administrator roles at the organisations as part of this profile).

- Technical research roles at the Machine Intelligence Research Institute, which we cover in a separate profile.

- Founding new effective altruist organisations.

- The charities recommended by GiveWell or Animal Charity Evaluators, because the advice would be quite different.

What roles are there?

The main type of roles at these organisations are:

- Research – including fundamentals research (Centre for Effective Altruism, Foundational Research Institute), research into donation opportunities (GiveWell, Open Philanthropy, Animal Charity Evaluators, Founder’s Pledge), and research into the social impact of careers (80,000 Hours).

- Marketing & outreach – includes writing content for social media, managing online ad campaigns, writing newsletters, optimising website conversion rates, speaking to the press, giving talks at events.

- Product management – includes working out which products there is demand for by talking to users and analysing data, co-ordinating the work of teams involved in building products, and planning long-term product development. Examples of ‘products’ produced by EA organisations include CEA’s EA Funds, and our job board. (More about what product managers do.)

- Web development & design – for example building and maintaining websites; creating images and graphics such as logos, icons, illustrations and charts.

- Operations – includes finance, accounting and HR roles. Activities include setting up accounting software, managing a bookkeeper, filing annual accounts, getting visas for staff, ensuring all legal compliance is done, deciding which healthcare plan to get.

- Administrators & assistants – wide ranging activities including managing schedules of senior staff, accepting visitors, organising office social events, purchasing office food supplies.

- Management – managing teams of people in any of the above roles, setting organisational strategy, fundraising, and hiring new people.

Why is working at an EA organisation high impact?

If you’re a good fit for one of the positions, and believe in the ideas of effective altruism, we think that working at an EA organisation is one of the highest-impact things you can do with your career.

We have obvious reason to be biased since we’re one of these organisations ourselves, but hear us out.

Track record of success

In the last five years, many of the organisations in the community have been far more successful than we expected, for instance:

- The charity evaluator GiveWell grew the amount of money moved to its recommended charities from $5 million in 2011 to $110 million in 2015. Some (but not all) of this growth was driven by partnering with the foundation Good Ventures, which expects to donate around $8 billion over the next few decades.2 Together they set up Open Philanthropy, which advises Good Ventures on where to give. Open Philanthropy also recommended over $100 million in grants to areas outside of GiveWell’s recommended charities in 2016, such as a $16m grant to support work on biosecurity and $5.6m to start the UC Berkeley Center for Human-Compatible AI.

Giving What We Can encourages people to pledge to donate 10% of their income to organisations that will most effectively improve the lives of others. They’ve grown the number who have taken the pledge from 165 at the start of 2012, to 2,500 in Jan 2017, to over 9,000 in 2024.

The AI risk organisations, such as the Future of Humanity Institute, the Future of Life Institute and the Machine Intelligence Research Institute have taken the concern for AI safety from a niche topic, into an issue that’s taken seriously by many of the leading AI projects and researchers.3 Funding for research into the control problem and related issues has doubled each year since 2014.

Founders Pledge encourages entrepreneurs to make a legally binding commitment to donate at least 2% of their personal proceeds when they sell their business. Since its launch in 2015, more than 800 entrepreneurs and investors have pledged with Founders Pledge, with $247 million committed to charity, across over 700 companies that are worth a collective $60 billion. Pledgers include the founders of Jawbone, Shazam, SwiftKey, and DeepMind. What’s more, in 2016, they partnered with Y Combinator, the world’s most famous startup accelerator. All founders going through the accelerator are now encouraged and recommended to pledge.

And we like to think 80,000 Hours is doing pretty well too.

The people working at these organisations often feel like they’ve done far more good than they could have done in other options, or ever expected to do in their life.

Even recent hires often make huge contributions, for example:

- Tara Mac Aulay started at CEA in early 2015 and was put in charge of the newly created community & outreach division at the Centre for Effective Altruismin August 2016 and grew the rate of new people taking the Giving What We Can pledge in the second half of 2016 by over 50%.

- Ben Clifford joined Founders Pledge in 2016, quickly took on a lot of responsibility and became head of growth for the organisation. He now handles many leads that the CEO would previously have taken on. Since Ben joined, Founder’s Pledge has raised over $100 million in legally-binding pledges.

Why are we seeing these successes?

Partly it’s because the organisations work closely together and benefit from the broader success of effective altruism as an idea, as well as the associated community. For instance, when Will MacAskill released the book Doing Good Better, that benefited all the organisations in the community. At 80,000 Hours, we’ve learned a huge amount from Holden at GiveWell, which helped improve our advice and strategy. This kind of sharing and cooperation is common. Read more about why being involved in the community helps.

Work on some of the most urgent problems

Another reason why working at an EA organisation is high impact is that many of the organisations focus on particularly urgent, neglected problems, such as global priorities research, risks from artificial intelligence and promoting effective altruism. You can see our reasoning for why we think these are among the most urgent global issues in this article.

Flexibility to change problem areas

Many effective altruist organisations also have some flexibility to change which problem areas they work on, so if other areas look more promising in the future, they can switch to working on those. For example Founder’s Pledge, Raising for Effective Giving, and Open Philanthropy can change which areas they direct money into in the future. At 80,000 Hours we can change which problem areas we encourage people to work in. And many of the organisations have actually changed where they focus over time – we explain some of our changes here. This flexibility is especially important to people who expect their opinions about the highest-priority areas to change (like we do).

High-leverage approaches

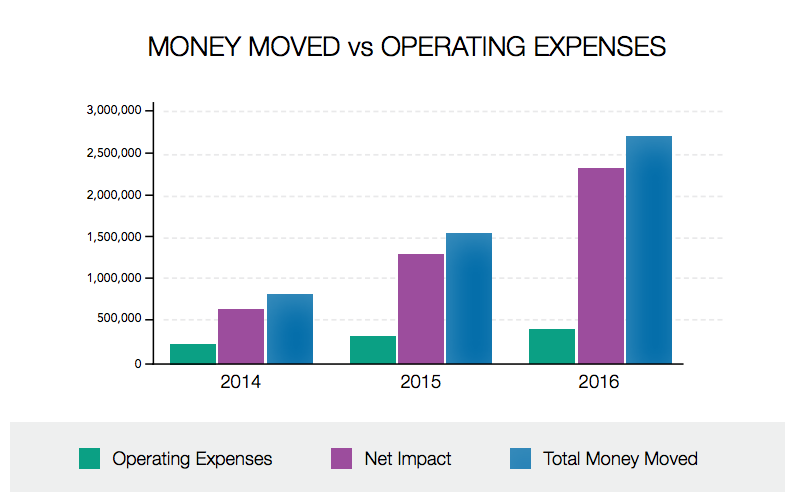

Many organisations also use especially high-leverage strategies, such as fundraising for top charities. For example, The Life You Can Save moved $2.7 million to its recommended nonprofits in 2016, while spending around $300,000 on its operating expenses. That means that for every dollar they spent, they raised ~$9 for their recommended nonprofits.

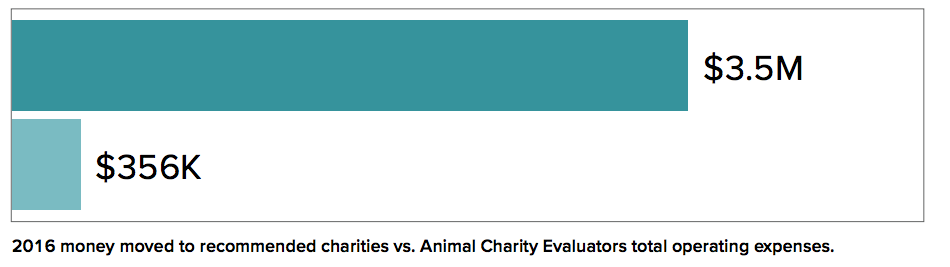

Similarly, Animal Charity Evaluators, moved over $3.5 million to its recommended charities in 2016, while spending $356,000, influencing nearly $10 for every $1 spent.

But won’t I be replaceable?

Some people worry that since a lot of people want to work at effective altruist organisations, if you don’t take a job, someone else who’s capable will do it, so you won’t have much impact. They also often think that they should earn to give instead – take a high earning job and donate to these organisations, since their donations won’t be replaceable.

We think that this is the wrong way to analyse the impact of working at EA organisations. We think you’re less replaceable than this analysis suggests, and that you’ll often have more impact working at an EA organisation than in earning to give. Why?

Many organisations are talent constrained

The first reason is that you won’t always be replaced – if you don’t take the job, the organisation might not fill the role for years. This often seems to be the case: there are roles the organisations have been trying to fill for a while, but haven’t been able to.

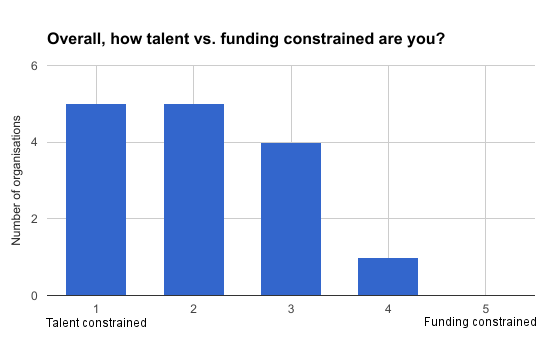

Indeed, in a recent survey, the majority of the organisations said they’re more talent constrained than funding constrained:

Why are EA organisations predominantly talent constrained? The key reason is that the organisations want to grow, and there are a number of large donors supporting the organisations, such as Open Philanthropy. These donors are usually willing to provide funds for anyone who can make a significant contribution. The community also has a good track record of attracting new large donors. This creates a situation where anyone above the bar gets hired and is not replaceable.

Why don’t the organisations simply raise salaries to fill the roles? They’re looking for an unusual sort of person — someone who’s really into the ideas of effective altruism – and offering more salary doesn’t do much to attract this kind of person (the supply of labour is inelastic). So, although raising salaries would help, they’d have to pay a lot of money for a small gain.

Another factor is that hiring takes up a lot of senior staff time – you need to source candidates, train them, test them out, and many won’t work out. Moreover, a bad hire could easily harm morale, take up a lot of time, or damage the reputation of the organisation, so there is a lot of risk. This means that it takes a long time to convert funding into good new staff, creating a talent bottleneck. But if a potential hire takes a short amount of time to evaluate, train and manage, they often wouldn’t get replaced for a long time.

To get a sense of how much value you create by working at an EA organisation, we asked the organisations how much funding they would have traded for their most recent hire. They gave an average of $126,000 – $505,000 and a median of $77,000 – $307,000 per year.4 Some of the organisations gave figures as high as $1m. There is incentive to inflate these figures in order to attract hires,5 but it at least suggests that these hires are expected to have a major positive impact on the organisation.

This is substantially more than most people could donate, even if they work in one of the highest-paying industries. This suggests that if you could get one of these jobs, your personal fit is similar to other recent hires, and you think these organisations are effective, it would be better to do that than to earn to give.

However, one important advantage of earning to give is that you retain complete flexibility over where you donate in the future. Given this, and the fact that the figures may be inflated, we think earning to give could be competitive if you would donate more than $100,000 per year. We talk more about how to compare direct work to earning to give later – the answer depends on your specific situation. For example, if you’d be an especially good fit at one of the larger organisations, it could be better to work there than even to donate $1m per year.

Spillover effects

So we’ve seen the first reason you’re less replaceable than is sometimes assumed is that for many roles at EA organisations if you don’t take the job, it likely won’t get filled for a long time (if ever). The second reason is that even if someone else would get hired if you didn’t take the job, you could still have a big impact. This is because by taking the job, you free up the person who would have replaced you to take another job. Since this person is also likely to be focused on social impact, they’ll probably do something else valuable, like working at another EA organisation, or earning to give. Then they might free up someone else, and so on.

This spillover effect means that at some point another role gets filled that wouldn’t have been filled otherwise. At worst, an extra person gets hired for the marginal role in the community.

Here’s a simplified hypothetical case, where you are considering whether to work at GiveWell (though we’ve seen similar real cases):

| You take the job | You don't take the job | |

|---|---|---|

| Role at GiveWell | You | Alice |

| Role at CEA | Alice | Bob |

| Role at Founders Pledge | Bob | No one |

Analysing the exact size of these spillover effects is difficult, but one thing is clear: they mean your impact is greater than a simple analysis of replaceability suggests. (In upcoming work, we argue that comparative advantage is the key rule of thumb to focus on when swapping people among roles in the community.)

So, for both reasons, we don’t think it’s usually true to say you’re “replaceable” in these roles. Rather, to sum up:

- If you have good fit with the role, you’re probably not easily replaceable to the organisation – you can roughly gauge how much value you’d create by asking the organisation how much in donations they’d trade to have you working there.

- Even if someone else would take the role if you didn’t, if you take the job you’ll free the other person up to do something else high-impact, further increasing your impact.

As a very simple rule of thumb, if you might be a good fit for one of these roles, then it’s likely among your highest-impact options. This isn’t to say that working at an EA organisation is always the best option. We come back to which options might beat it and when later on in the profile.

How good is the career capital?

Career capital consists of the skills, connections and credentials that put you in a better position to make a difference in the future. Here’s an overview of the pros and cons of the career capital you get by working at EA organisations:

| Pros | Cons | |

|---|---|---|

| Skill development | - Influence & responsibility early on - Autonomy helps with improving time-management and self-motivation - Can test fit for wide range of roles | - Value of expertise tied to success of EA movement - Lack of senior mentorship - Less formal training |

| Credentials & prestige | - Can get impressive achievements due to high levels of responsibility - Some impressive affiliations (Y Combinator, Oxford, Good Ventures) | - Less brand recognition than e.g. McKinsey, World Bank or top PhD programs |

| Connections | - Strong connections with EA community | - Connections less valuable if EA movement stops growing |

| Progression & exit options | - Well positioned for senior positions in EA organisations - Connections in EA community allow exits into wide range of sectors | - Career progression less clearly defined than in more established paths like consulting |

| Character | - Lower chance of losing altruistic motivation than most other paths | |

| Runway | - Harder to build up savings than in private sector roles |

More detail on the main pros and cons:

Achievements

As we’ve covered, many effective altruist organisations have had impressive achievements in the last few years. By working at one of the organisations, you have the chance to be part of achievements like these, especially if you have good personal fit. This is because effective altruist organisations are effectively startups, meaning you can gain a lot of responsibility quickly. You’ll often be managing projects, line managing staff, and contributing to organisational strategy much earlier than in larger organisations. For example Tara, who we mentioned earlier, was put in charge of the Community and Outreach Division at CEA in just over a year. If you’re into effective altruism, it can also be much more motivating to work at these organisations, which makes you more likely to excel in your work and gain impressive achievements.

Connections

You’ll be at the centre of the effective altruism movement, and build strong connections in it. Many people in the community feel like being part of the effective altruism community has enabled them to meet some of the most impressive people they’ve ever met. The community includes people working in a wide range of sectors, including tech, finance, government, the nonprofit world and academia. This will give you lots of other options to get jobs later — referrals from people in your network are among the most important factors for getting a job. For example, Hauke moved to working at the Center for Global Development, a leading US think-tank, thanks partly due to people he met whilst working at Giving What We Can.

If you think the EA community will keep growing, then the value of these connections just gets stronger over time. (Read more about the benefits of being part of the EA community in this article.)

Personal growth

Many people working at EA organisations feel like they’ve learned a huge amount. One reason for this is that you get a high degree of autonomy in how you do your work, which helps you learn to manage your time well, motivate yourself and be able to work independently. Job roles are also less rigidly defined than in larger, more established organisations, meaning that you can try out many different tasks and functions, which is especially valuable early on in your career.

You’ll be surrounded by colleagues who regularly share self-improvement and self-care tips, who try to be humble with their views, open to criticism and open to changing their minds. You’ll also gain better knowledge about how to have an impact with your career, as you’ll stay in the loop on the cutting edge of effective altruist research (a lot of discussion happens internally at organisations), and the altruistic culture significantly reduces the chance that you’ll lose your motivation to use your career to help others.

By joining effective altruist organisations now, you’re also positioning yourself for senior positions with a lot of influence, because you’ll build a lot of knowledge and connections that are hard to gain for people who join later.

Credentials

Even though effective altruist organisations are less widely recognised and prestigious than organisations like Google, McKinsey or the World Bank, they nonetheless do have some impressive credentials. For example, the Centre for Effective Altruism recently went through Y Combinator, the world’s most famous startup accelerator; the Future of Humanity Institute is a research institute at the University of Oxford; and Open Philanthropy is partnered with the multibillion foundation Good Ventures.

Downsides for career capital

There are of course, downsides. Some of the most serious include:

- Your career capital is tied to the success of the effective altruism movement. If the movement stops growing or fails, then the expertise and connections you build will be less valuable (though you will have still built connections with lots of interesting people). This is comparable to the risk of working at startups in general, where there’s a chance the sector you work in will stagnate or shrink.

Lack of senior mentorship. Most managers at effective altruist organisations are around 30, meaning there is less opportunity to get mentorship from people who are far into their careers. If you’re over 25, you might get mentorship from more experienced people in other roles.

Less investment in formal in training. Since the organisations are startups, they have pressure to grow quickly, so you won’t get sponsored to do an MBA like you might in consulting. Instead, you are expected to learn on the job and often have to take responsibility for your own training.

Harder to build up savings than in private sector roles. Salaries vary widely depending on the organisation, role, location, and level of seniority. Entry level salaries at the most competitive organisations typically pay ~$50k to ~$80k in high-cost-of-living areas in the US. The most competitive entry-level positions at those organisations typically pay near the high end of that range. Pay may vary outside that range at other organisations or for specific positions.

We think that these salaries are roughly what you need to be happy, but compared with jobs in the for-profit sector, it is harder to build up a savings buffer to withstand financial difficulties, and to make career transitions which require retraining. It can also be more difficult for people with children. That said, the organisations are often willing to pay more to get the right staff, especially if you have specific skills, like web engineering. Many are also happy to pay more to people with greater financial needs. At more senior levels, salaries range from $60,000 – $180,000 in the US.

Overall, working at EA organisations is a good option for career capital if:

- You have good personal fit for the roles.

- You think the ideas of effective altruism will continue to gain traction and and the community will keep growing.

- You expect the organisation to succeed.

It’s less good if you want more formal training and senior mentorship, or if you want to keep your options open in another path, like politics or academic research.

Read more about whether working at EA organisations is good or bad for career capital.

Other positives

- Working at effective altruist organisations gives you a sense of contribution, which increases job satisfaction and motivation. We think you get more of a sense of contribution than in most jobs, such as consulting and many PhDs, although it’s probably less than in roles that most tangibly help people, such as working on the ground in international development.

- You often get a high degree of autonomy in what hours you keep and how you do your work, which increases job satisfaction. There is also less bullshit and pointless rules that almost always come with working at larger organisations, which means you are likely to be more motivated and achieve more.

Other downsides

- People sometimes worry that working at effective altruist organisations doesn’t lead to concrete foreseeable future career options. As we’ve argued above, you are likely to build skills and connections which mean you’ll have good opportunities in the future. However you might still feel uneasy not knowing what the future holds, even if on reflection you believe that you’ll have good future career options.

- As with other startups, there is a risk of your organisation running out of funding (though this hasn’t happened to any of the major organisations), or substantially changing its strategy, meaning you could lose your job. It is also harder to hide poor performance in smaller organisations than in larger ones, so if you don’t perform well you are more likely to lose your job.

- If you want to work in-person at an effective altruist organisation, you’ll have to be based in Oxford, Cambridge or London in the UK, the San Francisco Bay Area in the US, Vancouver in Canada, Berlin in Germany, or Basel in Switzerland. We think that these are good places to move to, but it can be difficult if you have family ties elsewhere. Some organisations, like Animal Charity Evaluators and The Life You Can Save only have remote teams, which can be harder for staying motivated.

- Less clearly defined job roles and loose management structure can be stressful and demotivating for some people. People who only perform well with clear tasks and structures may struggle.

How to choose between working at EA organisations vs. other options

There are lots of other very high-impact positions with good career capital, including the following list. We think the key factors for choosing between these are your personal fit and comparative advantage relative to others in the EA community.

- Machine learning PhD (with the view to working on AI risk).

- Economics PhD at a top school.

- PhDs relevant to working on biosecurity, genetic engineering, cultured meat.

- Policy and government roles, especially those relevant to technology policy.

- AI risk research

- Founding new effective nonprofits.

You don’t need to consider your comparative advantage if you are choosing only between options where you wouldn’t get replaced. In those cases you should just go with the option with the best personal fit (and direct impact and career capital).

When choosing between working at EA organisations and other options, it’s helpful to get concrete about the specific roles you are considering. Often the decision turns on the specifics of each option. Here are some more specific comparisons:

Should I earn to give or work at EA organisations?

First, we recommend that you always directly ask the organisation at what level of donations they would become indifferent between you working for them and you donating to them.

If you could donate substantially more than this amount, that suggests you’ll have more impact if you earn to give. If you would donate less than this amount, that suggests you’ll have more impact working for the organisation. However, if you would donate somewhere else that you think is more cost-effective, you need to consider whether the impact of those donations would be greater than the value the organisation places on you working for them.

Second, you should consider how uncertain you are about which problem areas are best to work on, and how much you expect to change your views in the future. The more uncertain you are, the more that favours earning to give because of the greater flexibility it gives you. However, as we noted above, many EA organisations are also quite flexible, so earning to give only gives you a modest advantage in this respect.

Third, you need to compare the career capital of the specific roles you are considering. We have a checklist for doing this here. When assessing the career capital of EA organisations, it will largely depend on the quality of the team and the chances of success of the organisation. If you want more senior mentorship and widely recognised credentials, this favors earning to give at large tech firms, in consulting, or in finance.

Some other considerations are:

- Your view on how talent vs funding constrained the highest priority problem areas in general are. The more you think they are talent constrained and will continue to be in the future (we give some reasons for expecting this here), the more this favours working at EA organisations.

- If you’re already earning to give and it’s going well, then that favours continuing. (Also if you’re a major advocate for earning to give, for example if there has been press coverage about you pursuing it, then that favours continuing.)

Should I do a PhD or work at EA organisations?

In general, the time between your undergraduate degree and starting a PhD is a good time to explore and test out different options. Strategically, it’s much better to do this before a PhD than it is after. This is because getting work experience before starting a PhD doesn’t really harm your chances of working in academia. But if you don’t take a job in academia immediately after you finish a PhD, you more or less close off that option.

So if you’re unsure between the two, aim to try out working for effective altruist organisations before you start a PhD. If you’re still unsure about working for effective altruist organisations after that, then you should probably do a PhD. You can read this post by Jess Whittlestone which describes how she decided between doing a PhD and working at EA organisations.

If you are considering staying in academia after you finish a PhD, you should probably stay in academia rather than taking a job at an effective altruist organisation. It is easier to go from academia to effective altruist organisations than the reverse. The community could also benefit from more experts in some academic fields.

Should I work directly on another urgent problem?

If you think there’s a specific problem that’s highly pressing, for example nuclear security, climate change, or pandemic risk, then it may be more effective to work directly on that problem, rather than addressing it indirectly through building the effective altruism community, or doing global priorities research at EA organisations. What should you do if you’re in this situation?

We’ll use the example of positively shaping the development of AI because we think it is one of the top problem areas to work on.

First, bear in mind that some effective altruist organisations work directly on AI safety:

- Centre for the Study of Existential Risk

- Future of Life Institute

- Machine Intelligence Research Institute

- AI Impacts

If you go work at one of these organisations then you will be working on AI directly.

Other effective altruist organisation also contribute to work on AI safety, though it isn’t their only focus:

- Open Philanthropy – one of their main focus areas is AI safety.

- Foundational Research Institute – some of their research focuses on issues in AI safety.

- Centre for Effective Altruism runs EA Global conferences, which often include sections on AI safety, and significant fraction of donations by Giving What We Can members go to AI safety. CEA also runs the Long Run Future Fund.

- 80,000 Hours – we’ve written various guides to working on AI safety and a significant proportion of people we advise one-on-one is focused on AI safety work.

- Raising for Effective Giving – raises money for nonprofits, including the Machine Intelligence Research Institute.6

One consideration for deciding whether to work on AI directly is your view on how it compares with other problem areas that effective altruist organisations work on. The more certain you are that AI is the most effective area to work on, and will continue to be in the future, the stronger the case for working on it directly. The less certain you are, the more that favours working at EA organisations, which let you maintain more flexibility. (Read more about the key arguments for and against working on AI safety in our problem profile.)

The other key consideration is your personal fit and comparative advantage. Who is likely to succeed in direct AI safety work differs significantly between the different paths:

- Technical AI safety research requires strong technical abilities (at the level of being able to get into and complete a top 20 PhD program in CS or maths). Since very few people are able to do this research, if you’re a good fit for it, it’s likely to be your comparative advantage over working at EA organisations in non-technical research roles. Read more about technical AI research.

- Policy research on AI usually requires a Master’s or PhD in computer science, economics or policy, but doesn’t require top-end technical skills like technical research. The broad skill set is similar to research roles at effective altruist organisations, so many people may have similar fit for both policy research and research at effective altruist organisations. However, there is currently a lack of people in the effective altruism community doing AI policy research, so if you’re a good fit for it, we’d probably advise you to work in AI policy.

- Policy practitioners (who implement policy rather than develop new policy) require stronger networking, persuasion and negotiation skills than policy researchers, as well as a good understanding of the relevant issues in AI. The skill set is similar to outreach roles at effective altruist organisations, so unless you already have a good understanding of the issues around AI safety, your fit is likely to be similar for both roles. Read more about AI policy paths.

- Complementary roles are very similar to non-research roles at effective altruist organisations, so your personal fit is likely to be similar to those.

How to assess your personal fit

The organisations are looking for lots of different types of people and skills, so it’s helpful to get concrete about the specific roles you are considering when assessing your personal fit. But here are some general points to bear in mind.

As always, we think the best way to assess personal fit is to try out the work. We discuss some ways to do that in the final section on how to get a job.

What are the entry requirements?

Here is a rough sketch of what effective altruism organisations generally look for:

Research

- A track record of engaging with research in the community and making productive contributions to it.

- Having studied relevant disciplines at university, such as economics, statistics, philosophy or another quantitative field, helps, but isn’t necessary.

- For senior roles: advanced degrees in relevant disciplines, though exceptions are made for outstanding individuals. For very senior roles, such as Senior Fellow at GiveWell, also need 3+ years of research or policy related experience.

Marketing & outreach

- Experience with social media campaigns, content marketing, and event planning helps. Work, or volunteer experience that demonstrates you have strong interpersonal skills, clear writing and verbal communication and ability to manage projects.

- For more senior roles: 3+ years experience in marketing, growth or outreach roles, ideally in startups.

Product management

- 2+ years experience of product management in startups or tech-firms.

- Close involvement in the effective altruism community (this is important for all roles, but it’s especially important for product management since it requires a detailed understanding of the needs of the community).

Web development & web design

- For web development, 2+ years of experience (straight out of bootcamp is usually too junior). Ideally experience using the technologies the organisation uses.

- For web design, a degree in graphic design or a related field, 2+ years of experience.

Operations

- Experience in law, accounting, HR or project management helps. Work experience or volunteering that demonstrates excellent organisational skills, attention to detail, and ability to communicate clearly and professionally.

- For more senior roles: 3+ years of experience in operations, including leading teams. (Read more.)

Administrators & assistants

- Work experience or volunteering that demonstrates excellent organisational skills, attention to detail and ability to communicate clearly and professionally.

- For more senior roles: 2+ years of experience in operations, including leading teams.

Management

- 2+ years of management experience, with impressive track record of leading teams and executing projects.

- Strong affiliation with the effective altruism community.

- For academic project manager roles: formal or informal experience of project management, understanding of the relevant academic fields, often through a Master’s or PhD.

It’s a key requirement for many of these roles to care about the ideas of effective altruism, and organisations usually hire people who are already involved with the community in some way. Getting involved in the community can also give you the opportunity to learn about issues and make connections, as well as demonstrate your knowledge and skills in different areas.

Some of the best ways of getting involved include joining (or running) local or student effective altruism groups, participating in EA Global, helping community members out with projects, and participating in online discussions, like in facebook groups or on the EA Forum.

What’s the work like day-to-day?

The work varies depending on your role but some common features are:

- You usually have flexibility about the hours you work, autonomy about how you schedule your work day-by-day, and you can often work from home.

- Roles tend to be broad, so you have to prioritise and keep track of many competing demands and projects.

- Often there aren’t existing processes and guidelines for the tasks that you’re doing, so you have to develop your own processes.

- You often have input into the strategy of the organisation.

- You’ll be discussing effective altruism nearly every day.

Learn more:

- Working at EA organisations series: interviews with leaders

- Reflections from a recent employee on what it’s like to work at GiveWell

- Thoughts on what’s it’s like to work at GiveWell based on a 2 month trial in 2012

- Episode of the GiveWell podcast on what it’s like to work at GiveWell and what the hiring process is like.

What are the predictors of success?

Based on our experience, the people most likely to excel at EA organisations tend to have the following traits:

- They really care about effective altruism, and are happy to talk about it all day. This is one of the main things the organisations look for, and it can be hard if you don’t share the same level of enthusiasm about effective altruism as other staff.

They’re excited and enthusiastic about the mission of the specific organisation they work for. You get a lot of responsibility in these roles, and it can be hard to sustain the intensity and effort required to succeed without being excited by the mission and strategy of the organisation.

They’re self-directed, able to manage their time well, they can create efficient and productive plans, and keep track of complex projects.

What skills are the organisations most short of?

In August 2016, we surveyed 16 organisations in the effective altruism community and asked them “What types of talent does your organisation need?” Here are the options provided on the survey, along with the number of organisations which stated that they were looking to hire people for these roles:

| Role | Number of organisations | Percentage of organisations |

|---|---|---|

| Generalist researchers | 10 | 63% |

| Web developers | 7 | 44% |

| Management | 7 | 44% |

| Operations | 6 | 38% |

| Marketing & outreach | 5 | 31% |

| Administrators/ assistants | 5 | 31% |

Which specific jobs to apply to?

Choosing which organisation to work at

The main factors to consider are:

- How effective the organisation is. This can be assessed in terms of the problem area(s) it works on, the strategy it has for working on the problem area(s), and the quality of the team and how well it is run.

- How talent constrained the organisation is.

- The career capital potential of the specific role.

- Your personal fit and comparative advantage for the specific role. A very rough rule of thumb for working out your comparative advantage is to ask the people in charge of hiring at each organisation how good you’d be compared to other candidates they are considering. Your comparative advantage will often be the option in which you’d add the most value relative to other people considering working at that organisation.

Recommended organisations

See our current list of recommended organisations in the problem profile or on our job board.

It features organisations that: (i) are hiring, (ii) are more talent constrained than funding constrained, and (iii) have a track record of success.

What are the best jobs right now?

We keep an updated list here:

However note that many positions aren’t openly advertised and positions get created for people who are a good fit for organisations.

How can you get these jobs?

Many of the organisations only want to hire people who really care about the ideas, so they are unlikely to hire people who aren’t already involved in the community. There are also many unadvertised jobs, and others get created for specific people. So, the key is to participate in the community. Here are the best steps for getting involved:

- Sign up for the effective altruism newsletter and read Doing Good Better.

- Attend an effective altruism global conference.

- Use this to meet more people. Learn about the organisations, their strategies, their hiring needs. Read more about how to do this.

Once you’re involved the community, you need to demonstrate your ability to do the work well. The organisations usually hire people who have a track record of working in the community or have referrals from other community members. If you already have relevant experience, and have referrals from people in the community, this might be enough. Otherwise, the best way to prove your skills is to do a project. Doing this will also be a great help in testing out your degree of personal fit. Here are some ideas:

- Help to run a local EA group. It gives you experience in talking about effective altruism and you can easily get a couple of people to take the Giving What We can pledge. Read here for more details.

- Volunteer at an EA Global or EAGx conference.

- Give feedback on work in progress by people in EA organisations. You can do fact checking, give feedback on which parts are hard to understand, which other sources the authors may have missed, etc. This facebook group is one place where people post things they’d like feedback on. If you know people at EA organisations you can also get in touch with them directly and ask them to send you things they could use feedback on.

- Write up literature reviews or reports on things relevant to EA organisations and send them to the organisations, or publish them on the EA forum. Here are some examples on the EA forum.

For more ideas, see this list of potential projects, and this guide to getting more involved with effective altruism.

Some interviews with people currently working at effective altruist organisations

- How the audacity to fix things without asking permission can change the world, demonstrated by Tara Mac Aulay

- Michelle hopes to shape the world by shaping the ideas of intellectuals. Will global priorities research succeed?

- The world’s most intellectual foundation is hiring. Holden Karnofsky, founder of GiveWell, on how philanthropy can have maximum impact by taking big risks.

- Why it’s a bad idea to break the rules, even if it’s for a good cause

- Why daring scientists should have to get liability insurance, according to Dr Owen Cotton-Barratt

- Tanya Singh on ending the operations management bottleneck in effective altruism

- Finding the best charity requires estimating the unknowable. Here’s how GiveWell tries to do that, according to researcher James Snowden.

- David Roodman on incarceration, geomagnetic storms, & becoming a world-class researcher

Want to work at an effective altruist organisation? We want to help.

We’re happy to help people one-on-one who want to get a job at one of these organisations. If you want to work in this area:

Get in touch

Notes and references

- The effective altruism community is a global community of people who care deeply about the world, make benefiting others a significant part of their lives, and use evidence and reason to figure out how best to do so.↩

- “Joining the GiveWell staff in the meeting was Cari Tuna, the president of Good Ventures, a foundation she and her husband, Facebook co-founder Dustin Moskovitz, founded with their roughly $8.3 billion fortune. The couple plans on giving most of that sum away”. Vox – You have $8 billion. You want to do as much good as possible. What do you do? by Dylan Matthews on April 24, 2015. _↩

- See for example this list of top AI researchers who take AI safety seriously. (Archived link)↩

- The question was: “For the last person you hired, how much in donations would you be willing to receive to be indifferent between hiring and not hiring them?” Since the question was ambiguous whether the donations are once-off or annual, we think these amounts are likely to be between an average of $126,000 – $505,000 and a median of $77,000 – $307,000. The lower bound is calculated by dividing the original numbers by 4, the average time spent in a job by someone in their late 20s. We’ll reword this question for the next survey. See more details about the survey.↩

- Though there are also incentives to give lower figures in order to avoid employees demanding pay rises.↩

- They raised $121,657 for MIRI in 2016. REG Annual Transparency Report 2016 (Archived link)↩