#34 – Politics is so much worse because we use an atrocious 18th century voting system. Aaron Hamlin has a viable plan to fix it.

#34 – Politics is so much worse because we use an atrocious 18th century voting system. Aaron Hamlin has a viable plan to fix it.

By Robert Wiblin and Keiran Harris · Published May 31st, 2018

In 1991 Edwin Edwards won the Louisiana gubernatorial election. In 2001, he was found guilty of racketeering and received a 10 year invitation to Federal prison. The strange thing about that election? By 1991 Edwards was already notorious for his corruption. Actually, that’s not it.

The truly strange thing is that Edwards was clearly the good guy in the race. How is that possible?

His opponent was former Ku Klux Klan Grand Wizard David Duke.

How could Louisiana end up having to choose between a criminal and a Nazi sympathiser?

It’s not like they lacked other options: the state’s moderate incumbent governor Buddy Roemer ran for re-election. Polling showed that Roemer was massively preferred to both the career criminal and the career bigot, and would easily win a head-to-head election against either.

Unfortunately, in Louisiana every candidate from every party competes in the first round, and the top two then go on to a second – a so-called ‘jungle primary’. Vote splitting squeezed out the middle, and meant that Roemer was eliminated in the first round.

Louisiana voters were left with only terrible options, in a run-off election mostly remembered for the proliferation of bumper stickers reading “Vote for the Crook. It’s Important.”

We could look at this as a cultural problem, exposing widespread enthusiasm for bribery and racism that will take generations to overcome. But according to Aaron Hamlin, Executive Director of The Center for Election Science (CES), there’s a simple way to make sure we never have to elect someone hated by more than half the electorate: change how we vote.

He advocates an alternative voting method called approval voting, in which you can vote for as many candidates as you want, not just one. That means that you can always support your honest favorite candidate, even when an election seems like a choice between the lesser of two evils.

While it might not seem sexy, this single change could transform politics. Approval voting is adored by voting researchers, who regard it as the best simple voting system available. (For whether your individual vote matters, see our article on the importance of voting.)

Which do they regard as unquestionably the worst? First-past-the-post – precisely the disastrous system used and exported around the world by the US and UK.

Aaron has a practical plan to spread approval voting across the US using ballot initiatives – and it just might be our best shot at making politics a bit less unreasonable.

The Center for Election Science is a U.S. nonprofit which aims to fix broken government by helping the world adopt smarter election systems. They recently received a $600,000 grant from Open Philanthropy to scale up their efforts.

Get this episode now by subscribing to our podcast on the world’s most pressing problems and how to solve them: type 80,000 Hours into your podcasting app. Or check out the transcript below.

In this comprehensive conversation Aaron and I discuss:

- Why hasn’t everyone just picked the best voting system already? Why is this a tough issue?

- How common is it for voting systems to produce suboptimal outcomes, or even disastrous ones?

- What is approval voting? What are its biggest downsides?

- The positives and negatives of different voting methods used globally

- The difficulties of getting alternative voting methods implemented

- Do voting theorists mostly agree on the best voting method?

- Are any unequal voting methods – where those considered more politically informed get a disproportional say – viable options?

- Does a lack of general political knowledge from an electorate mean we need to keep voting methods simple?

- How does voting reform stack up on the 80,000 Hours metrics of scale, neglectedness and solvability?

- Is there anywhere where these reforms have been tested so we can see the expected outcomes?

- Do we see better governance in countries that have better voting systems?

- What about the argument that we don’t want the electorate to have more influence (because of their at times crazy views)?

- How much does a voting method influence a political landscape? How would a change in voting method affect the two party system?

- How did the voting system affect the 2016 US presidential election?

- Is there a concern that changing to approval voting would lead to more extremist candidates getting elected?

- What’s the practical plan to get voting reform widely implemented? What’s the biggest challenge to implementation?

- Would it make sense to target areas of the world that are currently experiencing a period of political instability?

- Should we try to convince people to use alternative voting methods in their everyday lives (when going to the movies, or choosing a restaurant)?

- What staff does CES need? What would they do with extra funding? What do board members do for a nonprofit?

The 80,000 Hours podcast is produced by Keiran Harris.

Highlights

…there’s actually a really good track record in the US for passing ballot initiatives on single winner voting methods, so we expect the likelihood of winning some to be pretty high.

The way that we look at it is instant runoff voting has been passed as a ballot initiative in a number of cities, but we see approval voting as producing better outcomes, and having better political dynamics compared to instant runoff voting. Approval voting is also so much easier, and it avoids a lot of the problems.

If instant runoff voting can win, then surely, a simpler voting method that produces good outcomes and has good dynamics should also be able to do it.

An interesting theme that comes up with a voting method, when you’re only dealing with two candidates, the voting method doesn’t matter so much, but it becomes really important when you have more than two candidates.

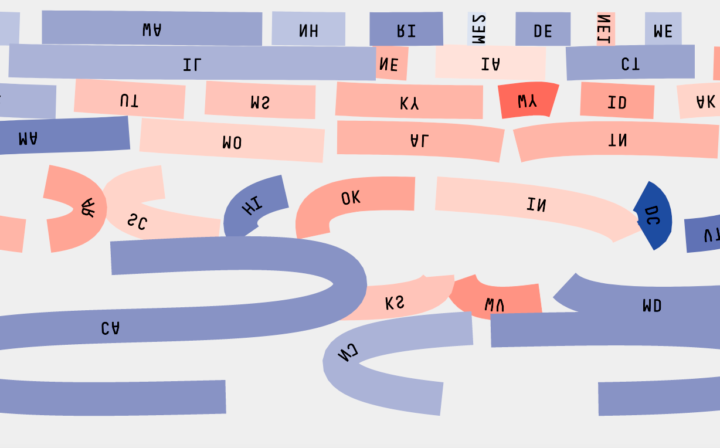

There’s an interesting phenomenon that can occur when you have a three-way race where all three are competitive and there’s a moderate candidate. There’s this phenomenon called the Center Squeeze Effect, which has the candidate in the middle have their votes split on either side, so here what you’re essentially having is first choice preferences being split.

The person in the middle gets split from the person on the right, and the person on the left, and they can just get a sliver of the vote, even though they appeal to the broadest breadth of the electorate.

In terms of improved welfare, the concept that we’re looking at is we have people who are elected, and these people who are elected are in charge of spending vasts amounts of money; more than the richest of the rich can spend.

In addition to being able to spend these vast amounts of money, they also determine policies that affect our day-to-day lives, in very substantial ways, and so the idea of choosing the voting method is that we’re given an effectual way to be able to decide who sits in those seats, that are able to make those types of decisions for us. That’s the underlying concept for why this makes sense as a target.

A voting method, it doesn’t just determine the winner; it gives us a flavor for all the candidates involved, and on top of that, it actually influences what your options are to begin with. As an example, in the 2016 election, Michael Bloomberg decided not to run in the election, because he thought he was going to split the vote with Hillary Clinton, and have Trump win, so that’s why he didn’t run.

We have a voting method that causes people not to run, because they’re afraid of mucking up the election, and nobody wants to be accused of being a spoiler as well, and nobody wants to go in and think, well, I don’t have the same kind of name recognition as other people, if people just hear my views, that’s not going to be enough; they’re not going to vote for me.

Articles, books, and other media discussed in the show

From the episode

- RSVP for CES dinners with Aaron coming up soon in SF, New York, Brooklyn, DC and Philadelphia

- Aaron adds further detail to some points in the show where he thinks his answers were too brief

- The Center for Election Science website

- The Problems with First Past the Post Voting Explained by CGP Grey

- The Case Against Democracy by Caleb Crain in the New Yorker (covers unequal voter systems)

- Louisiana gubernatorial election, 1991, Wikipedia.

- Other Wikipedia articles on: Arrow’s impossibility theorem, First-past-the-post voting, Condorcet methods, United Kingdom Alternative Vote referendum, 2011

- Another recent unequal vote method: My thoughts on quadratic voting and politics as education by Tyler Cowen

Books

- Electoral Engineering: Voting Rules and Political Behavior (Cambridge Studies in Comparative Politics) by Pippa Norris

- Gaming the Vote: Why Elections Aren’t Fair (and What We Can Do About It) by William Poundstone

- Electoral Systems: A Comparative Introduction by David M. Farrell

- Real Choices/New Voices by Douglas J. Amy

Relevant conferences

Relevant articles from The Center for Election Science

- This is approval voting

- This is not approval voting

- Why approval voting is good:

- Why approval voting is better than other alternatives:

- Center for Election Science implementation strategy

- Article about their recent funding from Open Philanthropy

Transcript

Robert Wiblin: Hi listeners, this is the 80,000 Hours Podcast, the show about the world’s most pressing problems and how you can use your career to solve them. I’m Rob Wiblin, Director of Research at 80,000 Hours.

Today’s episode goes deep into the why and how of voting reform. If you’re interested in politics, economics, collective decision-making or philosophy, then this should be an exciting episode for you. If none of those gets you going, you might find this episode goes further into the details than you’re looking for.

We’ve recently attracted a few thousand new subscirbers, so I just want to point out to everyone that the blog post attached to every episode comes with links we’ve carefully chosen to help you achieve some level of expertise in the topics we cover. I strongly recommend checking them out.

Also, in case you didn’t know, the blog post for almost every episode comes with a full transcript of the conversation. I’ll be honest that there are sometimes transcription errors in there – but if you read much faster than you listen, you might prefer to consume the show that way. It’s also helpful if you want to find a quote later, on or pull something out to share with other people.

Finally, the posts list all the topics we cover, and a list of key points from the episode. There’s a link to the blog post in the text attached to the episode in your podcasting software.

Without further ado here’s Aaron Hamlin.

Robert Wiblin: Today I’m speaking with Aaron Hamlin. He’s the Executive Director of The Center for Election Science; a U.S. nonprofit, which aims to fix broken government by helping the world use smarter election systems. CES recently received a $600,000 grant from Open Philanthropy to scale up its efforts.

In 2014, he also co-founded the Male Contraceptive Initiative, where he worked for three years. Before that, he completed graduate degrees in both education and public health, before completing a JD, and briefly practicing law.

He’s written for Deadspin, Independent Voter Network, and The Telegraph, and his work has been featured in Popular Mechanics, National Public Radio, and Scientific American, among many others. Most importantly, he’s a regular listener to the 80,000 Hours Podcast, so thanks for coming on the show Aaron.

Aaron Hamlin: Thank you. It’s a pleasure being here.

Robert Wiblin: We plan to focus on what good electoral reform would look like, what the benefits might be, and whether it’s at all realistic to achieve it, but first, describe for us the problem that you see yourself as trying to solve, Aaron.

Aaron Hamlin: What we’re looking at here is the voting method itself. To get terminology out of the way, when I say voting method, what I mean is the information that you put on the ballot, so say choosing one, choosing as many as you want, ranking, scoring on a scale, and then what that information is done with.

How you’re using that information to calculate a result, and that’s called the voting method. That’s what we’re mainly looking at when we’re looking at these problems.

Robert Wiblin: Okay, so in the U.S. and the U.K., the voting system is basically that everyone picks one name, and one name only, and in Australia where I’m from, you have to number everyone in order of preference. That’s what we’re talking about.

Aaron Hamlin: That’s right.

Robert Wiblin: Why hasn’t everyone just picked the best voting system already? Why is this an interesting and complicated issue?

Aaron Hamlin: It’s a tough issue because it’s a tough problem to analyze. With a lot of things, you might find a nice, easy metric to use and then given that metric you can say, “Oh, well we measured all these things according to this metric and this one came out on top. We’ll just use this one.”

Well, with voting methods, there are a number of considerations to look at. No particular voting method is solid on all these considerations. These are considerations like what kind of winner you get.

If people, on average, seem to be happy with a particular winner, do you get certain anomalies? How consistent is the method? When a method messes up, how badly does it mess up? How frequently does it happen? How does it treat newcomers?

People that lose, even if they lose, are they given an accurate reflection in support? Here, this is looking at single winner method issues, but there are also a number of considerations in terms of metrics that you would consider for multi-member issues.

You might look at, for say a multi-winner election method, does it give proportional outcomes? For a certain percentage of the electorate, if say 10 percent of them choose a particular party, say they choose 10 percent for instance, does the number of elected officials roughly hit at that 10 percent, or is it way off? Do they get no seats, or do they get many more than they should?

Those are the types of considerations that you look at when you’re dealing with whether a voting method is fair or whether it makes sense to use that method in a particular context, and also things like complexity, what ballot design does it have? Is it simple? Is it hard? These are the types of things that we’re looking at.

Robert Wiblin: We’ll come back to a whole lot of different voting systems and the various pros and cons in a minute, but to make this more concrete, can you us an example of where a bad voting system produced a clearly bad outcome?

Aaron Hamlin: Yeah. There’s one fun, and a little bit depressing election that happened and 1991 for the Louisiana Gubernatorial election. Louisiana, they use what’s called a Jungle Primary, which means that you take all the candidates and you have them all run together.

Then you take the top two and they go together in a runoff, head-to-head. In the 1991 election, there were really three main contenders there within the Jungle Primary. You had Buddy Roemer, he was a moderate candidate and who was the incumbent governor.

You also had a couple others, who were a bit interesting characters. One was Edwin Edwards, and Edwin Edwards, he had served in government before, and had had some allegations of bribery, and he was kind of a shady character and that was something that people were pretty aware of, that he was a bit of a shady character.

The other main front-runner was a guy named David Duke and David Duke was known for being a Wizard in the Ku Klux Klan, and so also an interesting character. You had these three candidates that were running in this Jungle Primary, and what the voter is doing is that each voter is choosing just one candidate out of all these candidates, and here we’re talking about three main front-runners.

There were some other candidates, but three that were getting the majority of the attention, and then the two candidates with the most votes would go on to this runoff. The funny thing is, Buddy Roemer, the more moderate of the bunch, did not make it to the runoff.

Instead, Edwin Edwards, the corrupt politician, and David Duke, the Ku Klux Klansman, were the ones that made it to the runoff.

Robert Wiblin: Obviously, you and I would have preferred the compromise character, but why is it clear that that was just an error in the system, due to a bad voting system, rather than just voters having preferences that you and I don’t like?

Aaron Hamlin: One way that we can get an idea that this wasn’t right, aside from just it smells of something that is not right, is that when they took polling information to look at how candidates would do head-to-head against each other, Buddy Roemer against Edwin Edwards, Buddy Roemer wins.

Buddy Roemer versus David Duke, Buddy Roemer wins. If Buddy Roemer ran against either of these two head-to-head, he would have won easily, but the mere fact that it was a three-way race meant that he was knocked out.

Robert Wiblin: That was because of vote splitting, I guess? That some of the people who liked him moderately were taken away in the first round to the other two candidates?

Aaron Hamlin: That’s right. An interesting theme that comes up with a voting method, when you’re only dealing with two candidates, the voting method doesn’t matter so much, but it becomes really important when you have more than two candidates.

Then the voting method that you choose becomes really important. There’s an interesting phenomenon that can occur when you have a three-way race where all three are competitive and there’s a moderate candidate.

There’s this phenomenon called the Center Squeeze Effect, which has the candidate in the middle have their votes split on either side, so here what you’re essentially having is first choice preferences being split.

The person in the middle gets split from the person on the right, and the person on the left, and they can just get a sliver of the vote, even though they appeal to the broadest breadth of the electorate.

Robert Wiblin: They’d win an election against every other candidate one-on-one?

Aaron Hamlin: Yes.

Robert Wiblin: Is this a common occurrence? Is it common for the voting system to produce suboptimal outcomes, or even disastrous outcomes as in this case?

Aaron Hamlin: It tends to occur more often when you have a competitive election, where there are a number of candidates. Primaries are likely one area where you would see that because you have a lot of candidates; that they tend to have a lot of similarities and overlap, so you can have more of this vote-splitting type effect going on.

Robert Wiblin: I guess, an effect of the potential for vote-splitting is that, in these plurality voting systems, where just the candidate with the most first preferences wins, is that you tend to get consolidation to just two parties, because every side wants to make sure that their vote is never split because that greatly weakens their chances.

Aaron Hamlin: There’s a separate reason why you get two parties as a consequence of a particular voting method.

That goes to a political science idea called Duverger’s Law. Duverger’s Law is a predictor for the number of parties based on the voting method. It looks at two factors: one is the amount of support that a particular candidate, or a party need in order to get elected, and when you’re talking about a single winner election, that amount of support is more than anyone else.

That raises the threshold, so that it makes it difficult for third parties or independents that can hit that support. Then the other factor that Duverger’s Law looks at is whether it’s possible for a voter to fearlessly be able to support their honest favorite, even if the person doesn’t look like they’re going to do particularly well.

You really need that in order to give third-party candidates, and these other candidates the ability to increase their support, because if you’re … As a voter, if you’re looking at a third party, you’re an independent, and you’re saying, I don’t think they’re going to do very well; you’re likely not going to vote for them.

You want your vote to be effectual, so you’re likely going to choose amongst the front-runners, but if you have a voting method that doesn’t let you do that, and it forces your hand to say vote for the lesser of two evils, well, now you’ve got a problem and third parties are going to have a problem, too.

If you’re able to address at least one of these two factors, that is being able to have a lower threshold to be able to get in there, which say, proportional voting methods do, or you have a voting method that allows you to work on supporting your honest favorite, that’s also going to help for allowing for another party to thrive.

Duverger’s Law is a little bit of a misnomer in some ways. It really acts as a large predictor, so there are other types of factors that can be predicted in terms of whether you’re going to have more than two parties, but the voting method is, by and large, a predominant factor.

Robert Wiblin: Just before we go into voting theory in detail, which countries and kinds of elections does The Center for Election Science think about? Is it just government elections in the U.S., or is your scope broader than that?

Aaron Hamlin: We think about voting methods all over, and here, we spend a good amount of time looking at single winner voting methods, and right now that’s predominately our focus, although, we also look at, to some degree, multi-winner methods.

There are a number of countries that use better multi-winner methods arguably than the U.S. and some other countries that do elections similar to how we do, so for instance, you have countries like Denmark, Iceland, Sweden, Norway, they use a lot of proportional methods.

They also use some things like leveling seats, which makes it so that you can have a certain threshold, say 5 percent in order to make it so that a party needs to hit that threshold of support in order to get anyone elected for a particular seat.

Some of these countries that use proportional methods can use features like leveling seats to make it so that if the number of people within a party are maybe off compared to what it should be, they can add extra seats to even that out. To make sure that it’s more proportional than it otherwise would be.

You have some countries like that, that use nice features in order to lead towards more proportional outcomes, but when we’re talking in the single winner space, so things like executive offices, like Mayor, Governor, President, those types of things, we see, really, a lot of bad voting methods all around, across the world.

We see first-past-the-post used quite a lot, when you’re only choosing one person and the person with the most votes wins. Sometimes we see a runoff, which was exampled with the 1991 Louisiana Gubernatorial election, and David Duke and Edwin Edwards entered the runoff, which is a spoiler.

If you haven’t read through, Edwin Edwards actually beat David Duke, and interestingly enough is going and running again in other elections. Not successfully, but attempting to run in other elections, so even to the kind of examples that even countries that are using runoffs, there are still some serious issues with using runoffs.

We know that there are voting methods, single winner voting methods, that get around some of these issues, and yet we’re still seeing a lot of governments, even newer governments, that are re-visiting their systems or creating new systems. They’re still using these really bad voting methods, either first-past-the-post or a runoff system.

Even if they’re doing something, say instant runoff voting, that’s still getting into some of the issues that we see with traditional runoff systems. It’s just simulating that process.

Robert Wiblin: All right. Let’s talk about the various reform options. Most jurisdictions in the U.S. and the U.K. just use first-past-the-post voting, so you get to vote for one candidate and the candidate with the most first preferences wins.

What are the various different options that they could have for reducing opportunities for tactical voting and reflecting the actual preferences that the electorate has, rather than having perverse outcomes, like a candidate that would beat every other candidate, one-on-one, failing to win the election.

Aaron Hamlin: A really simple way that we tend to like, and we push as an organization for single winner government elections, is the voting method called ‘approval voting’. With approval voting, what you do is you merely select as many candidates as you want, not just one. If you want to choose just one, you can do that, but you have the option to select as many as you want.

We’re not talking about ranking. We’re talking about merely choosing as many as you want, and then the calculation just being summative like it normally would be. That particular method is really simple, which is nice. When you can use a simple method that gives you the types of outcomes and behavior that you want, it’s normally pretty good to go with that method.

It’s also robust to a lot of anomalies that you wouldn’t like to have occur, so with vote-splitting, it’s very robust at vote-splitting; if you have similar candidates that are running, because people can choose multiple candidates at the same time, it helps to guard against that.

It also has a really nice property to it, which is nice for independents and third parties. That is that with approval voting, when you can choose as many candidates as you want, you can always put your full support behind your honest favorite candidate.

What that means is, say there’s an independent or a third party candidate that you really like, but you’re looking at them and you think: ‘God, this person is never going to win, what I should really be doing is looking just among the top two competitive candidates, maybe the major parties, and choose a lesser of the two evils among them.’ With approval voting, you don’t have to do that; you can have your cake and eat it too.

Under an approval voting election, what you can do is you can support that third party or independent candidate that you really like, and in addition to that, if it looks like the candidate maybe is not going to be able to take on one of the other leaders, and really dominate, and it looks like you maybe want to hedge your bets with one of the other two front-runners, what you can do is you can choose a lesser of two evils in addition to supporting your honest favorite.

That makes a big difference, because now that third party or independent candidate, that candidate can build their support over time. Also, it means that they can’t be marginalized the same way. If we’re using first-past-the-post or party voting, when you can only choose one candidate, third parties and independents get an artificially low amount of support. Not only do they typically lose, but they get an artificially low amount of support, which means that they are marginalized unfairly.

They can bring good ideas to the table that are popular with people, but because they’re perceived to be a losing candidate, they just simply don’t get that support of a party voting, but with approval voting, we see time and again through research and through other polling, that these candidates get a much more accurate reflection of support, and that’s exciting, because that means when they bring these good ideas to the table, they don’t get marginalized unfairly.

Robert Wiblin: Okay, so approval voting avoids the vote-splitting perversity and it means that candidates are more likely to get an accurate reflection of how much the electorate likes them in general in their vote share.

I know that approval voting is your preferred favorite, and it seems to be that the voting system that The Center for Election Science is mostly promoting at the moment. What are the biggest downsides of that system, and are there any alternatives that we should be considering as well?

Aaron Hamlin: Yeah, so every voting method has anomalies that can occur with it. There are theorems out there, like the Gibbard-Satterthwaite Theorem, which says that every voting method can have some kind of tactical voting vulnerability.

Tactical voting, that’s when a voter expresses information on their ballot in a way that isn’t accurate for their actual preferences, but they do it, because voting that way optimizes the likelihood of the outcome that they want to see.

With approval voting, probably one of its heaviest criticisms is that it can tend to cause some people to choose only one candidate, because they don’t want to create extra competition for that candidate, and you can have an approval voting election where a lot of people just choose one candidate, but we would argue that that’s not something that’s fatal.

Really, what’s important here is that when it’s important for a voter to choose more than one candidate, that they had that ability, and that when they don’t have that ability, then it becomes a real issue, so for instance, there may be, within an election, and a lot of people maybe don’t care about some of the non-front-runners. Maybe they just simply aren’t very good candidates.

In that kind of circumstance, maybe they only choose one candidate, and that’s not a big deal, or say your honest favorite candidate is a front-runner, and you don’t want anyone competing with that candidate and there’s really no one else that you have to hedge your bets against.

Then in that case, it makes sense to choose only one candidate. Another interesting thing here is that even when a lot of people say choose only one candidate, having just a portion of people, say 10 or 15 percent, choose more than one candidate, can still make a big difference.

10 to 15 percent within an election, that can easily mean a difference between a win and a loss, or one candidate winning versus another candidate winning, so it can change the outcome of an election, even when a few number of voters decided to choose more than one candidate.

The other issue that comes up is, even when you have a lot of people choosing only one candidate, it can still make a big difference with the people that choose multiple candidates in terms of how that reflection of support is given for third parties and independents.

Robert Wiblin: Okay. I guess, for those who choose to just vote for one candidate, they’re probably no worse off than they would have been, if they could only vote for one candidate; they just also have the option of expressing a wider range of preferences as well.

Aaron Hamlin: That’s right. There’s no harm for them for having that option.

Robert Wiblin: Is that really the greatest weakness of approval voting? Are there no situations where you have a particular kind of allocation of support between different candidates where a Condorcet winner, that is a candidate that would win on a one-on-one fight with every other candidate, could lose in approval voting, or is that just extremely rare?

Aaron Hamlin: With approval voting, one of its nice properties is that it tends to elect, what’s called a Condorcet winner, and as a recap for clarity, a Condorcet winner is a candidate who can beat every other candidate head-to-head, if it was just between those two candidates.

The candidate that can do that, with every other candidate, is a Condorcet winner. Another interesting thing about that, is that a Condorcet winner does not always exist, just like a candidate with majority support does not always exist.

Robert Wiblin: Interesting. Okay, but approval voting will almost always choose one if one does exist?

Aaron Hamlin: Correct. Approval voting is very good at electing a Condorcet winner. It’s not to say that it will do it every single time because, like I said, voting methods aren’t good at being able to fulfill a lot of certain criteria in an absolute sense, but they can perform really well on a particular criterion.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. You said approval voting is a little bit vulnerable to tactical voting, where someone might only vote for one candidate, kind of for the same strategic reasons that they might vote for a particular candidate in first-past-the-post voting, but does it violate any of the other, or can it violate any of the other ideals of a voting system?

Aaron Hamlin: Part of the rationale for looking at choosing only one candidate would be a criterion called, later-no-harm, which gets back to the idea of you don’t want to create extra competition for your favorite candidate, so for instance, let’s look at the worst-case-scenario for an approval voting election, whereas an individual voter, you see that one of your favorites is in the lead and there a couple other competitors.

One, you really would hate to see get elected and another, you would just be kind of all right with, and so there, to avoid the catastrophic result, you may choose a candidate that has a lot of commonality with what your ideals are and the policies, but maybe doesn’t quite fit the same way that your favorite candidate does, so there, you may choose a candidate, and that candidate may wind up winning as a consequence.

There, at the individual level, you have a failure where you just get a compromise candidate, but the interesting thing about that is that, at the individual level, there may be a little bit of a loss there, but by choosing a compromise candidate, that’s something that, while there may be a little bit of loss at the individual level, at the group level, that tends to be a candidate that appeals to the broadest space.

Another instance here, is that here, when we’re talking about a failure at the individual level with approval voting, the failure is not an enormous one; we’re talking about maybe not getting your favorite candidate, but as a result of the way that you vote, maybe getting a compromise candidate.

Compare that to the type of loss that you might see in another type of voting method where, instead of by the way that you express your ballot, instead of getting maybe your favorite candidate, you get a really terrible outcome, which is possible with other voting methods.

The worst-case-scenario that you see with an approval voting election, is that at the individual level, you may get a compromise candidate, which may not be a terrible deal for the election at the group level.

Robert Wiblin: Okay, so it fails more gracefully. Before we go on to talk about other voting systems, do you want to just respond to the common objection that approval voting, and probably everything else we’re going to discuss here, allows people to vote more than once, which I think is a common complaint among people who are used to first-past-the-post voting where you only get to vote for one candidate?

Aaron Hamlin: Yeah. I think the idea there is that the criticisms that some voting methods may violate, which called, “one person, one vote.” The concept behind one person, one vote is that the weight of one person’s ballot counts as more than others in an unfair way, and as a quick spoiler, they don’t violate one person, one vote.

In fact, the concept of one person, one vote, goes back to some Supreme Court decisions in the U.S., like Baker versus Carr, Reynolds versus Sims, and they were looking at some cases where you’d have a district that has way fewer voters than another district, and yet, the smaller district would get the same number of seats, which was weird, which meant that, if one district had a population that was 10 times smaller than another, essentially, the weight of those people’s vote, within that district, was 10 times greater.

That’s not what is going on with these voting methods, so for instance, say we have six candidates, you really like one candidate, and were using an approval voting election, and you choose that one candidate, and say I like four other candidates that aren’t that one candidate that you like, and I choose all four of those.

Well, my ballot doesn’t count for four times as much as your ballot does, and neither of the people that we voted for, if we just count our two ballots, are in the lead over the other, so neither one of us is getting an extra unfair weight as a result of using a particular voting method.

Robert Wiblin: I suppose one way of explaining would be, in approval voting, if you had an election with six different candidates, if you voted for all six of them, in a sense, you got six votes, but of course you won’t change the outcome at all, because you voted for every single one and you haven’t distinguished between them.

I suppose another way to think about it might be that, everyone gets the same number of votes, they get six votes, they get to decide whether they say yay or nay to six different candidates?

Aaron Hamlin: Yeah, that’s right.

Those are other explanations that also get at the same underlying idea there, and there are a number of elections that we use with current voting methods that allow us to express the number of votes for candidates in the different ways. So, for instance, in a lot of U.S. elections for a city council, for instance, we use what’s called block plurality voting, where there are five people being elected, and say there are 10 candidates or something, a voter would be told that they can vote for no greater than five candidates.

You can have somebody that chooses five candidates out of those 10; you can have another person that chooses three candidates out of those 10, and here you have a different number of candidates being voted for on different ballots, but neither voter is at a disadvantage, merely because of the way that they decided to express their vote, given the voting method, and that’s something that we already use right now.

Robert Wiblin: This makes me think, if I was voting in an election with approval voting, and there were six candidates, how do I decide how many to vote for? Obviously, I don’t want to vote for all six of them. That that’s pointless. I could vote for one, and so I boost the one that I most like, but is there some kind of medium that is optimal from a strategic point of view?

Aaron Hamlin: Yeah, so one simple heuristic that you could use is you could say, okay, well, who’s likely to win here? Like who are the front runners here? Then among the front runners, you would take a compromise. You would take the candidate among the front runners that you like.

Then in addition to choosing that candidate, you could choose everyone else that you liked more than that candidate too, which would take the place of other candidates that you really like, but maybe aren’t as viable.

You could look at it that way, such as choosing your favorite as another way, and then looking at is there anyone else that is likely to win, that you would also find acceptable; who is maybe not competing with your favorite.

You’re also considering things, like is there somebody else that you really don’t like, and is there perhaps someone that you may be able to hedge your bets with to keep that other person from winning, which really is not too far away from the way that we do it in current elections, in terms of the analysis.

Like say that there’s an independent or third party candidate that you like, normally you can’t vote for that person, but you’re looking at ways to hedge your bets against the other person that you don’t like.

You’re really doing the same scenario, only in addition to hedging your bets appropriately, you are also being able to offer that honest expression of support and really choosing the candidates that align with your viewpoint.

Robert Wiblin: Okay. Let’s move on to other voting systems now. I’m from Australia, where we have a system called single transferable vote. I think also called instant runoff, or in the U.K., alternative vote. Do you want to just describe that one and then explain its pros and cons, and maybe why you haven’t chosen to campaign in favor of that voting system?

Aaron Hamlin: Sure. I would offer a quick highlight of a nuance, which is that instant runoff voting is really a different voting method than single transferable vote. When we talk about something like instant runoff voting, we’re talking about a single winner voting method.

Whereas when we’re talking about single transferable vote, we’re talking about a multi-winner voting method; they have a lot of similarities with their algorithm and you can plop one on the other within a particular circumstance and get the same result, but it’s generally a good practice to separate single winner voting methods and multi-winner voting methods.

Robert Wiblin: Okay. Yeah, so I guess we use instant runoff for our Lower House, our House of Representatives, where we have single-member districts, and then I guess single transferable vote for our Upper House, where each state represent, elect seven different candidates.

Aaron Hamlin: Yeah.

Robert Wiblin: Yep, okay, yeah, so what are the pros and cons of that kind of approach in general?

Aaron Hamlin: With instant runoff voting, I think intuitively, it seems like you’re offering more information, and you are offering more information, and part of the issue with that is that, within the algorithm of instant runoff voting, you are only looking at one part of the ballot at any one point. Like the algorithm that is going through is only looking at the first choice preferences at any one point.

To step back for a moment to highlight what’s going on with instant runoff voting, the algorithm is saying, first, the voter is ranking their preferences from their first to their least preferred candidate. The algorithm is saying, does anyone have more than half of the first choice preferences among all these candidates?

If yes, then you have your winner there; if not, what’ll happen is you look at the candidate who has the least number of first choice preferences, that candidate is eliminated, and you look at the ballots that voted for that candidate as their top preference, and then you look to their next preference, and then the next preference is now treated as the first preference, and then you go through, run that algorithm again, and see if anyone has a number of first choice preferences that’s greater than half.

If yes, you have a winner; if not, you keep going through that until you do, and so there, it’s an element of an issue with instant runoff voting to begin with, and that it’s complicated. You have a number of rounds that are going on there, and being able to keep track of all those vote transfers between rounds, can be complicated.

With the expression part, it seems like you’re providing all the information, but the algorithm is only looking at first choice preferences at any one point, and it may not even look at the rest of your ballot, so even though you provided all this information, the algorithm may not even look at the rest of your ballot at all during the election, given what happens in the election.

That’s one part, and that it intuitively feels like you’re providing all this information, but we can’t forget that a voting method, it has multiple components to it. One component is the information that you’re providing. The other component though is, what is the algorithm for that voting method doing with that information?

That’s one element. You can also have things like anomalies that can occur, and to be fair, anomalies can occur with lots of different voting methods, so you can have it so that you rank a candidate as better, and that causes that candidate to lose, you can rank your favorite candidate as first, and that can wind up harming you and leading to a worse outcome.

That’s an issue that we see with first-past-the-post already with when we choose our honest favorite, causing an undesirable outcome to occur. Even though at the moment, highlighting some of the issues with instant runoff voting, it should be clear that first-past-the-post voting, or plurality voting is really awful.

We have our issues with instant runoff voting, but plurality voting is worse than instant runoff voting, so as a caveat, it’s always important to put that out there, in terms of making sure that we always know where the bullseye is, and that the picture of first-past-the-post is always on that bullseye.

Robert Wiblin: Okay. From my experience in Australia, single transferable voting seems to work reasonably well.

I think the case where you can get the most perverse outcome is where you want your second favorite candidate to get removed sooner, so that then their second preferences will be distributed among other candidates, and so you take a candidate who you actually preference second, and put them last, so that they’re more likely to get eliminated early, and then those votes go to another candidate that you might prefer a bit more.

There’s some room for tactical voting, though I think because Australia’s system is pretty two party heavy, that happens fairly rarely. In the case with multi-member districts in the senate, that there’s this quite regular occurrence, where the seventh member that’s elected in each state, is quite random, because often, they’re cobbling together a bunch of votes for tiny parties.

We’ve had members elected to the senate from the motorist enthusiast party that got well under one percent of the vote, because they managed to cobble together preferences from tons of micro parties, before they went to the major parties, but by and large, it seems to work okay.

Although, especially in the senate, often people have to vote. If they want to vote, or actually, in the past, if they wanted their vote to count, and they didn’t want to give their preferences to the parties to decide themselves; they would often have to number like 100 different candidates, which I’ve actually had to do.

Recently, that’s been changed, so you can choose how many candidates you want to vote for, and your vote just expires if there’s no further preferences, so once it’s removed, but yeah, it’s interesting to me that instant runoff and single transferable vote, that they seem to be more popular methods around the world than approval voting, but you seem to think that approval voting, it’s usually a superior system.

Aaron Hamlin: Yeah. Instant runoff voting, and single transferable vote have had some advantages, probably the academic history for them, and initial use was a lot earlier than with modern use of approval voting.

The academic literature on approval voting really begin in the late 1970s with Steven Brams and Peter Fishburn, they were … While there are some other people that looked at approval voting and identified the voting method, independently, the academic research really begin in the late 1970s, and then went from there.

These other voting methods really just really had a headstart, and from that headstart, they’ve been able to see more implementation, but they also had that initial gap too, from when the initial work is done a method, and then you have that gap between when you see the initial use, and then successions from there.

Robert Wiblin: The UK considered switching to single transferable vote, which they called alternative vote, in I think 2012/2013, they had an election about that, and they pretty decisively decided not to switch their voting system. Do you know what the reason for that was, and does this indicate why it might be hard to get any switch in voting systems?

Aaron Hamlin: I’m not quite as familiar with that particular campaign, so it could difficult for me to go on the nuances of that, but I can talk a bit about some of the campaigns in the US for alternative voting methods that look at instant runoff voting, for instance.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah, that would be great.

Aaron Hamlin: In the US, instant runoff voting has been implemented in a number of cities at the local level, and then it’s also been, more recently, pushed at the state level. That’s largely been successful, so there, the idea there, and this has been used previously with other types of alternative voting methods earlier in the 19th century, so this strategy has been taken up again to push instant runoff voting.

The way that’s been done is by using ballot initiatives at the local level, and that makes a lot of sense, and one of the reasons it makes a lot of sense is because if you are elected under a certain voting method, you really don’t want to have another voting method come along that could risk your re-election. You’d really like to have it be the same voting method that got you elected in the first place.

As a consequence, there’s a conflict of interest, with people who are already elected, choosing the method that’s going to be electing them in the future, and so to get around this conflict of interest, a ballot measure is a good way to-

Robert Wiblin: Take it directly the public.

Aaron Hamlin: Right, and circumvent that issue. We’ve seen over a dozen cities use and implement instant runoff voting, and it’s been pretty successful in getting it initiated. Although, there have been some repeals in some cities, and part of that is you have some complexities that come up with that particular voting method.

We can see some anomalies, and when that happens, people can get confused, and so sometimes you just get the wrong result, and people aren’t happy about that. As a consequence, it’s also been repealed in certain cities as well.

Robert Wiblin: Are there any alternatives, alternative systems that would be appropriate under particular circumstances that we should also consider?

Aaron Hamlin: Yeah.

We like approval voting for single-winner government elections, particularly here in the US, because one, it’s very simple, so you don’t get a big discrepancy between the voting method that we’re currently using, and the proposal, and it tends to avoid a lot of anomalies, tends to get you good results, but there are other situations where maybe we want to use a different voting method, and maybe that makes sense, so for instance, voting takes place in a number of different types of context.

If you’re using a voting method where there aren’t a whole lot of voters, say 20 or 30 or something, and you’re making a group decision, maybe something like score voting makes sense, so for clarity, with scoring voting, what you’re doing is you are scoring each candidate on a scale, say zero to five, and the candidate with the highest score, on average, is the candidate that wins.

Robert Wiblin: It’s a bit like how you review things on Amazon or IMDB?

Aaron Hamlin: Yeah, yeah. The nuances within the algorithm may be a little bit different, but that’s the idea. That’s certainly the expression element that’s occurring. One of the reasons why something like score voting is more appropriate when you have a small amount of voters is because you really, when you’re voting and you brought information, it’s a sampling.

When you have not a whole lot of people, or voters, then you have, from a statistical point of view, a lot of random error. With score voting, because you have more iterations of expression along a scale, that sensitivity actually reduces that error, so you’re more likely to hit the result that is good for the group.

Whereas with approval voting, when you have a small number of people, you may have an issue there, because the expression element doesn’t have a lot of sensitivity. With score voting, you’re getting, really, a lot of the features of approval voting, and it’s still an additive voting method, because you’re just taking the average or simply summing the scores.

You get a lot of the same features, but you also get that sensitivity. When you have a large number of voters, the sensitivity isn’t quite as important there. Having a large number of voters tends to compensate for that lack of sensitivity within the voting expression.

Robert Wiblin: Because you have lots of voters, and they have a distribution of how strongly they like something, and it tends to be the case that the thing that people like the most intensely is also the thing that most people are going to prefer.

Aaron Hamlin: That’s right.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah, interesting. Why not use this score voting? Because you were saying approval voting is basically like score voting, except that you only get two scores that you can give everyone, five starts or zero stars; why not allow all these gradients of expression for every candidate?

Aaron Hamlin: Yeah, and so the reason that we push approval voting so hard instead of score voting is that, with approval voting, we see that as being easier to implement as a practical sense. The ballots look virtually the same, except the direction so you can choose more than one, instead of just one, and that’s pretty much it.

Whereas with score voting, you’d have to change the ballot, you may have to tweak the voting machines a bit more, if you’re using a voting machine, but with approval voting, the ability to implement it is very simple, and the education campaign needed for that is not the same as should you be proposing another voting method that’s more complicated, like whether it be score voting, or instant runoff voting, or another voting method.

Robert Wiblin: With score voting, wouldn’t there be a really strong temptation to bury all of the candidates who you don’t like that much? Just to give everyone who dislikes zero stars out of five, to ensure that you’re not giving them any help to get elected?

Aaron Hamlin: Yeah, yeah, so some other tactics can appear under a score voting, because of the way that you’re allowed to express your ballot.

Say even like a candidate say one out of five, but they look like they may be somewhat competitive, and you may bury that candidate, that’s a particular tactic they can use under score voting, but while using that tactic, we would argue that the types of results that would create wouldn’t be as devastating as the types of anomalies that could occur under different voting methods.

Robert Wiblin: Okay, interesting. The reason to go for approval is just that it’s more straightforward, and people can understand it and it’s more likely to get up?

Aaron Hamlin: That’s right.

Robert Wiblin: Cool. Okay, so we’ve been through approval voting, score voting, single transferable vote; are there any other big candidates for voting reform?

Aaron Hamlin: I think those are some of the big ones. We spoke a bit about instant runoff voting. Single transferable vote is a proportional voting method that’s typically used for districts.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah, the multi-member districts.

Aaron Hamlin: Yeah, yeah, and one important thing about … Say we’re talking about using a proportional method within a district that’s electing multiple people at the same time. It’s also important to keep in mind the number of people that you’re electing at the same time.

If the number of people that you’re electing at the same time, say three, well, the proportionality is going to be worse, so there, in order to guarantee a seat, you’re going to need 25% of the vote using a single transferable vote method of when three people are elected, that uses something called the Droop Formula, in order to figure out what that is.

Proportional methods, when you have more people being elected at the same time, you tend to get more proportionality, which is why some countries use methods that elect an entire legislature or parliament at once, so that they can get more proportionality. In fact, some people argue that that gives too much proportionality, and that you get little tiny parties, and maybe we don’t want to see that kind of splintering going on.

As a way to compensate for that, with these huge legislative bodies that are using a proportional method in order to compensate that, they may say, in order to get elected, we need to at least have five percent of support in order to be able to get someone into office, so that’s a way of getting more of that proportionality, while at the same time, avoiding that super splintering effect.

Robert Wiblin: What makes the voting method specifically an important target, as opposed to other reforms that you might have of a political system?

Aaron Hamlin: Well, a voting method is really unique in the way that its role is played within electoral politics. When I say that, we’re always, as citizens, we have all these opinions about what policy should be, who should be in government, and while we’re doing all these things to express ourselves, whether it’s going and sharing things with friends, going to a protest, or lobbying our representatives, they really don’t have to listen to any of that.

The only thing that they are forced to listen to is our vote. That’s one time when they don’t have a say in the matter. If we cast our votes a certain way, and according to the voting method, it produces a particular result; they can’t ignore that, they have to abide by that.

This is our best tool, and because this is our best tool, in terms of what it’s capable of doing, we need to make sure that it’s an effective tool in order to be able to produce the outcomes that we want.

If we’re using a voting method, and that voting method doesn’t allow us to actually express our opinion, accurately or fully, then we’ve got a big issue, because if we’ve never expressed that information, there’s no way that information is going to be considered in the result for an election, and so because of that, we want to make sure that the voting method that we’re using allows us to express information that is capable of being used to produce a meaningful result.

Also, that the information that we’re expressing under this voting method, is accurate enough, so we’re not just using these tactical voting elements that are being pushed on us by the voting method, that that’s not occurring, so that we can present accurate information that is actually being able to be used in a meaningful way, so that we can get results that represent us.

If we’re using a bad voting method, well, we simply don’t get that, and then we just get these other opportunities that aren’t nearly as effective as being able to cast your own vote, and not being able to have that ignored.

Robert Wiblin: Okay, so if I had to summarize your views on this in just one sentence, I think it would be that first-past-the-post voting is terrible, approval voting seems like the best alternative, but other methods, including instant runoff, or score voting are also better, because first-past-the-post is so bad. Is that attitude typical of voting theorists, and is there a consensus, among people who study this topic, on where we ought to move?

Aaron Hamlin: Interestingly, there is. The London School of Economics and Political Science has an organization called, Voting Powers and Procedures.

A while back, they got a bunch of experts together, and they were trying to figure out, we have all these voting methods out there, and you had this collective, this group was a bunch of broad experts on voting methods, and they thought we should probably, since we got all these people together, we should maybe vote on what the best voting method is; that would be a fun thing to do.

Robert Wiblin: How did they choose how to do that?

Aaron Hamlin: Yeah, so they agreed by consensus, initially, just to use approval voting for simplicity. That was the way that they were going to express their votes on all these voting methods, and they had a number of different voting methods, including score voting, instant runoff voting, first-past-the-post, Condorcet methods, Borda count; all these different voting methods.

Here, we’re talking about single winner methods, so that’s the only thing that they were considering. Interestingly, so they were using approval voting, which meant that all these experts, they could choose as many options as they wanted. If they liked a bunch of different voting methods, they could choose all those voting methods.

I think out of the outcome from that, one of the more interesting things was … There was a clear winner, but there was also a clear loser in the bunch, and the interesting part about that, the loser, the losing voting method out of this group of experts, got zero approvals.

Robert Wiblin: Can I guess which one it is?

Aaron Hamlin: Feel free to toss in your guess.

Robert Wiblin: First-past-the-post, right?

Aaron Hamlin: Yeah, it was first-past-the-post.

Robert Wiblin: The top one was approval voting, I’m imaging?

Aaron Hamlin: Yep, it was approval voting.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah, so an approval voting system approves of approval voting, it’s very suspicious.

Aaron Hamlin: Instant runoff voting did do pretty well in that mini informal election, but approval voting was able to beat it pretty solidly, and then everybody just destroyed first-past-the-post, which is telling, and a bit depressing, because first-past-the-post is used all over the world for single-winner elections.

In the US, we talked a bit about multi-winner elections using proportional voting methods, the US doesn’t do that; the US uses winner-take-all, that is they have an opportunity to have multi-winner elections, and use proportional voting methods, but instead, they put people into individual districts, and they elect them one at a time, and the way they elect them one at a time, is typically to use first-past-the-post.

If you get lucky, maybe they use a runoff, but as we discussed already, runoff is not going to solve all of your issues.

Robert Wiblin: Yep, okay. It sounds like the reform you’re pursuing is very popular among people who think about this.

Before we move on and talk more about the potential benefits of voting reform, who’s working on it, and how likely it is to actually happen, I wanted to talk about some other potential changes that you could get in political systems, and get your thoughts on whether they’re also important targets for advocacy or research.

Do you think proportional representation, or changes in how parliaments are structured, how many houses you have, and the size of districts, and gerrymandering is another thing, is that reform attractable and potentially very high impact, and maybe why didn’t you choose to work on that instead?

Aaron Hamlin: The reason that we chose first to look at single winner methods was the tractability. In the US, there’s a bit more modern history there.

Although, interestingly, in the first half of the 1900s in the US, single transferable vote was used in a number of cities, and over a dozen cities, and was repealed in a number of them, except for really one for city council, which is Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. In quite a lot of European countries, I guess Germany most notably, that they have these proportional representation system that allows for quite a lot of different parties, and these fairly large districts that elect, model for different candidates to the parliament.

Do you have a view on whether that’s a good thing or a bad thing, setting aside whether it’s actually possible to get that in the United States?

Aaron Hamlin: Yeah, I would tend to say that compared to the United States, that it’s better, significantly better. One is, in the United States, we have a big issue with gerrymandering, which is just politicians drawing the lines to figure out who their own voters are, which is on its face, just slaps of nonsense, of something that shouldn’t be an issue.

What’s interesting about that is a lot of people look at different solutions for that, whether it be independent commissions, or a computerized line drawing as a way to have that be fair, but it seems to be, I would argue, a bit intrinsic to single-member districts, the type of bad outcomes that you can get with winner-take-all.

It’s not to say that it can’t be worsened by gerrymandering, and lessened by these independent commissions, but there are some inherent issues with winner-take-all; as an example, Canada has used independent commission since 1964, and the last two elections in Canada, we saw what are called false majorities, which means that a party has less than half of the votes, and yet, it has more than half of the seats, which is something that doesn’t make sense.

If you get fewer than half the votes, you shouldn’t get more than half of the seats, and that happened in the last two elections, and you would think that, if we were doing some fairer line drawing, that shouldn’t happen, but it does happen, and it seems to a consequence of winner-take-all elections.

If you use something like proportional representation, you see that these false majorities, or these manufactured majorities, you see that happen a lot less often when you use a proportional system.

Robert Wiblin: When I wrote on social media that I was going to interview you, quite a lot of people got in touch, asking about increasing voter turnout as an alternative to doing voting system reform. Do you think that that’s a valuable intervention, and something that can be done in practice?

Aaron Hamlin: I think part of it is how you increase better turnout, and you also have to ask why are people not turning out in the first place.

If you’re giving them a tool that’s not very effective, by using what is arguably the worst voting method there is for single winner elections, then you’re probably not going to get a whole lot of people excited about the effectiveness of their vote. Maybe one way to increase voter turnout is to give a real tool that allows them to cast a much more meaningful vote.

Another interesting part about voter turnout is that if you think about this in terms of sampling, so like when you’re doing a statistical sample, for instance, you don’t need to sample the entire population; you can sample a part of the population, and so long as that sample is representative of the population as a whole, it doesn’t matter that you didn’t sample everybody.

The issue becomes when the sample that you have is not representative, and so we have it so that systematically, certain people are not turning out to vote, perhaps because we’re giving them a terrible voting method, and their not feeling empowered, then if we create an incentive for them to turnout and vote, then I think we’re looking at a better scenario.

It’s not so much there that the voter turnout is higher, it’s that the people who turn out are more representative of the electorate as a whole. Another interesting idea here is that with voter turnout, we could also perhaps look at that as a proxy measure for the kind of faith that people have in the political system.

That if people aren’t turning out, and this goes back to the idea maybe they don’t feel like they are empowered as they should be, and even if they’re not recognizing the system main issue, perhaps they just think I don’t feel like I have an effectual vote.

Perhaps if they did have a meaningful way to vote, such as with the meaningful voting method, and they saw that is an issue, perhaps that would change their likelihood of turning out, and also making it so that the people who do vote, are more reflective of the entire electorate.

Robert Wiblin: A number of listeners also wanted me to ask you about possibilities for unequal vote weighting. Like an example of that might be requiring citizens to show an understanding of the electoral system in order to vote, or giving extra weight to voters who, for whatever reason, are considered wiser contributors to the system?

Obviously that has a pretty terrible history in the United States, as being used as a way of excluding people of color from voting, but can you see any way that unequal voter weighting could be used to improve the system?

Aaron Hamlin: Probably not. I would much rather go the route of more meaningful voting methods. The idea of giving a purposefully … Giving people less weight, and there, you’re actually directly violating one person, one vote. Yeah, I can’t see a whole lot of good coming from that.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. I used to be interested in possibilities for doing this in order to improve the understanding of the electorate, so you would give people who had a better understanding of policy issues more weight, but I think it’s important to explain to some listeners who might sympathetic to this, why I no longer think that that’s a very good idea.

Basically, to begin with, it’s an absolute political non starter, because people look at that and they see opportunities for all kinds of mischief, to basically exclude them, or to exclude a particular groups from being represented. A vote is two things, it’s both people contributing information that they know about, what kind of policies would be effective, and it’s also a whip that voters to have to make sure that politicians actually care about their welfare.

When particular groups are underrepresented, or not able to vote, or their votes aren’t given as much weight, then it tends to be the case that politicians spend much less money on them, and just don’t care about their welfare terribly much, so you can see that with Puerto Rico perhaps after a hurricane that went through there; they don’t get to vote for members of congress, and they don’t get to vote for president, and that seems to be reflected in the low level of interest that politicians have in taking care of their welfare.

The US constitution in the 14th amendment, precludes giving different weight to different voters, and also precludes trying to prevent people from voting, and I think with good reason, because it’s trying to make sure that politicians can’t choose their voters in this way, in order to say people who share my views, it’s because they’re smarter, and they should be given most of the weight, and people who disagree with me, it’s just because they’re misinformed and we should find ways of preventing them from being part of the electorate.

Aaron Hamlin: Yeah. You particularly don’t want people, designing the test, being the same people who are already elected.

Robert Wiblin: Right, but who else is going to do it, right? It faces some serious problems. I’ll put up some links to discussion of that issue, which I think listener might be interested in, but I guess this raises the general issue of voter ignorance, because if you take surveys of the electorate, you find that often they have very poor understanding of the most basic issues of how the system is designed.

I think most people don’t know how many senators their state has, let alone any more complicated information that they might need in order to vote wisely. Does that imply anything about voting reform? Does it suggest that we have to keep the system extremely simple, because just most people are trying to live their lives, and don’t have much time to allocate to thinking about voting?

Aaron Hamlin: I think, in general, if, particularly for single winner methods, if you have a solution that works reasonably well, and avoids a lot of the anomalies that you like to avoid, and it’s simple, then you should probably go with that method, until you get to the point where your electorate is more sophisticated, and then maybe after that point, then maybe you can consider more complicated voting methods.

That’s a bit of a barrier for proportional methods, because proportional methods, the algorithm component of that tends to be a bit more complicated.

I think with proportional methods, there’s a bit more trust involved, so people are just looking at the results, and looking at independent verification in order to have the confidence in the system, so that may be a bit of an exception to the rule, but you need to give people a bit of experience with alternative voting methods.

Letting them see the improved outcomes that can occur, and then after that confidence level is built up, then exposing them to more and more ideal solutions as they become more comfortable with added complexity.

Robert Wiblin: Okay, well, let’s return to assessing how good voting reform is as a cause, from an effective altruist, or an 80,000 Hours standpoint. We evaluate causes, as most of listeners will know, on three criteria; one is scale, that is how large with the benefits be.

Another is neglectedness, so how many people are already working on it. A third is tractability, which is how likely are you to be able to …

How hard is the problem to solve. Let’s take each of these in turn. Is there a way of measuring how large the benefits will be from having voting reform? Is there nowhere that this has been done, and we can see the benefits in terms of improved welfare?

Aaron Hamlin: In terms of improved welfare, the concept that we’re looking at is we have people who are elected, and these people who are elected are in charge of spending vasts amounts of money; more than the richest of the rich can spend.

In addition to being able to spend these vast amounts of money, they also determine policies that affect our day-to-day lives, in very substantial ways, and so the idea of choosing the voting method is that we’re given an effectual way to be able to decide who sits in those seats, that are able to make those types of decisions for us. That’s the underlying concept for why this makes sense as a target.

Robert Wiblin: Do we have a way of measuring the benefits between different countries, or different jurisdictions, where some of them have better voting systems than others today? In some places you have first-past-the-post voting, which is particularly bad.

In other countries, you have instant runoff, or single transferable vote, or multi-member districts. Can we see better governance in the countries that have, what we consider, better voting systems?

Aaron Hamlin: From what I’ve seen, so for instance, I believe it’s in Pippa Norris’ book, Electoral Engineering, when she had looked at, for instance, proportional voting methods compared to non-proportional voting methods, one of the things that stood out was, one, you had more women in government, particularly with closed party-list systems, but another that stood out was more egalitarian systems.

You had less income inequality compared to non-PR countries. That’s one area that I’ve read in terms of different types of social outcomes that have been different.

Robert Wiblin: You think just because government is so influential and the amount of money that it spends, and the amount of harm it can do, if the people in charge will make bad decisions, that having a system that better reflects the preferences of the electorate, is on its face, it’s going to be extremely important, even if we can’t precisely measure its value in dollars, or how much better policy it would be.

Aaron Hamlin: I would say so, yes.

Robert Wiblin: Okay. How big do you think this could get? My understanding is the Center for Election Science is pushing for approval voting to get tested at a local level, and then I guess you’re hoping to get it implemented in a lot more elections. How big could you see it getting? Could it end up being the system that we use to elect governments at the national level around the world?

Aaron Hamlin: I think so. Certainly not immediately, but the simplicity of this, and that there’s so many good things about approval voting, that it’s a difficult thing to put back in the bag, once it’s out there.

The practical approach for this is there’s been decades of research on approval voting in the literature, so it’s gone through the rigors of peer review, and scholarly analysis, and so the idea from here is just to get it implemented at the local level, show proof of concept, and then replicate that in other areas in the general geographic area, and then from there, go to other areas, in addition to larger cities. Then once you have a certain concentration from there, you could start to target states.

The way that government is structured in the US, once you hit the state level, you can start to think about hitting the federal level at the same time. Perhaps at a certain point down the road, once there’s enough saturation, I don’t expect this to be anytime soon, but further down the road, you can potentially look at something like approval voting being able to elect the president, which is due to the nice features about approval voting.

Because approval voting is so simple, it has some nice features called, this one particular feature called, precinct summability, which means that you could take totals from jurisdictions or states, and then take those totals, and then sum them up with other areas, and that makes it so that you can have totals at the national level.

The other nice component of this, is that if you have some states that are using plurality voting, and other states that are using approval voting, for the way that they do their votes, you can add those together in a way that is not really practical with other voting methods, so that if you have some hold-out states during the process of moving towards a system that elects a president using approval voting, you can do that along the way.

There are different approaches for doing that, like one approach right now is of using a national popular vote with priority voting is using, what’s called an interstate compact, which is an agreement between states, that has them sign on to allocate their electoral votes, once enough other states have signed on, so that their electoral votes total 270, which is more than half the total electoral votes.

Then they would just go ahead and have their electoral votes go towards the national popular vote winner, regardless of what their state’s national popular vote winner is. It’s difficult to have that kind of compact when an individual state is using a voting method other than plurality voting, or approval voting.