#112 – Carl Shulman on the common-sense case for existential risk work and its practical implications

#112 – Carl Shulman on the common-sense case for existential risk work and its practical implications

By Robert Wiblin and Keiran Harris · Published October 5th, 2021

On this page:

- Introduction

- 1 Highlights

- 2 Articles, books, and other media discussed in the show

- 3 Transcript

- 3.1 Rob's intro [00:00:00]

- 3.2 The interview begins [00:01:34]

- 3.3 A few reasons Carl isn't excited by strong longtermism [00:03:47]

- 3.4 Longtermism isn't necessary for wanting to reduce big x-risks [00:08:21]

- 3.5 Why we don't adequately prepare for disasters [00:11:16]

- 3.6 International programs to stop asteroids and comets [00:18:55]

- 3.7 Costs and political incentives around COVID [00:23:52]

- 3.8 How x-risk reduction compares to GiveWell recommendations [00:34:34]

- 3.9 Solutions for asteroids, comets, and supervolcanoes [00:50:22]

- 3.10 Solutions for climate change [00:54:15]

- 3.11 Solutions for nuclear weapons [01:02:18]

- 3.12 The history of bioweapons [01:22:41]

- 3.13 Gain-of-function research [01:34:22]

- 3.14 Solutions for bioweapons and natural pandemics [01:45:31]

- 3.15 Successes and failures around COVID-19 [01:58:26]

- 3.16 Who to trust going forward [02:09:09]

- 3.17 The history of existential risk [02:15:07]

- 3.18 The most compelling risks [02:24:59]

- 3.19 False alarms about big risks in the past [02:34:22]

- 3.20 Suspicious convergence around x-risk reduction [02:49:31]

- 3.21 How hard it would be to convince governments [02:57:59]

- 3.22 Defensive epistemology [03:04:34]

- 3.23 Hinge of history debate [03:16:01]

- 3.24 Technological progress can't keep up for long [03:21:51]

- 3.25 Strongest argument against this being a really pivotal time [03:37:29]

- 3.26 How Carl unwinds [03:45:30]

- 3.27 Rob's outro [03:48:02]

- 4 Learn more

- 5 Related episodes

The spectacular collision of comet Shoemaker-Levy with Jupiter in 1993 prompted the US Congress to fund NASA to track all large asteroids in our solar system.

Preventing the apocalypse may sound like an idiosyncratic activity, and it sometimes is justified on exotic grounds, such as the potential for humanity to become a galaxy-spanning civilisation.

But the policy of US government agencies is already to spend up to $4 million to save the life of a citizen, making the death of all Americans a $1,300,000,000,000,000 disaster.

According to Carl Shulman, research associate at Oxford University’s Future of Humanity Institute, that means you don’t need any fancy philosophical arguments about the value or size of the future to justify working to reduce existential risk — it passes a mundane cost-benefit analysis whether or not you place any value on the long-term future.

The key reason to make it a top priority is factual, not philosophical. That is, the risk of a disaster that kills billions of people alive today is alarmingly high, and it can be reduced at a reasonable cost. A back-of-the-envelope version of the argument runs:

- The US government is willing to pay up to $4 million (depending on the agency) to save the life of an American.

- So saving all US citizens at any given point in time would be worth $1,300 trillion.

- If you believe that the risk of human extinction over the next century is something like one in six (as Toby Ord suggests is a reasonable figure in his book The Precipice), then it would be worth the US government spending up to $2.2 trillion to reduce that risk by just 1%, in terms of American lives saved alone.

- Carl thinks it would cost a lot less than that to achieve a 1% risk reduction if the money were spent intelligently. So it easily passes a government cost-benefit test, with a very big benefit-to-cost ratio — likely over 1000:1 today.

This argument helped NASA get funding to scan the sky for any asteroids that might be on a collision course with Earth, and it was directly promoted by famous economists like Richard Posner, Larry Summers, and Cass Sunstein.

If the case is clear enough, why hasn’t it already motivated a lot more spending or regulations to limit existential risks — enough to drive down what any additional efforts would achieve?

Carl thinks that one key barrier is that infrequent disasters are rarely politically salient. Research indicates that extra money is spent on flood defences in the years immediately following a massive flood — but as memories fade, that spending quickly dries up. Of course the annual probability of a disaster was the same the whole time; all that changed is what voters had on their minds.

Carl suspects another reason is that it’s difficult for the average voter to estimate and understand how large these respective risks are, and what responses would be appropriate rather than self-serving. If the public doesn’t know what good performance looks like, politicians can’t be given incentives to do the right thing.

It’s reasonable to assume that if we found out a giant asteroid were going to crash into the Earth one year from now, most of our resources would be quickly diverted into figuring out how to avert catastrophe.

But even in the case of COVID-19, an event that massively disrupted the lives of everyone on Earth, we’ve still seen a substantial lack of investment in vaccine manufacturing capacity and other ways of controlling the spread of the virus, relative to what economists recommended.

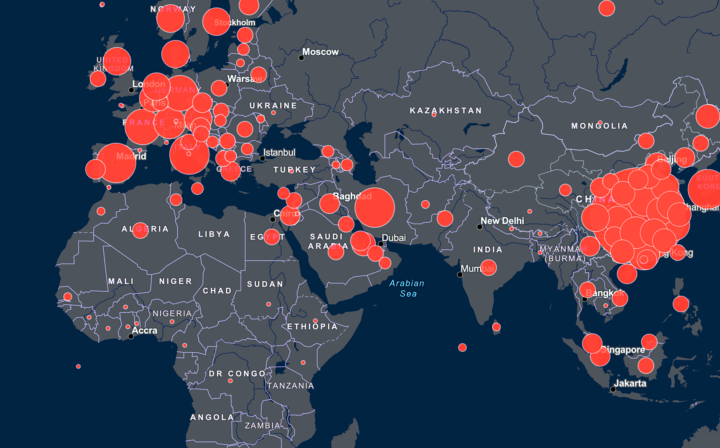

Carl expects that all the reasons we didn’t adequately prepare for or respond to COVID-19 — with excess mortality over 15 million and costs well over $10 trillion — bite even harder when it comes to threats we’ve never faced before, such as engineered pandemics, risks from advanced artificial intelligence, and so on.

Today’s episode is in part our way of trying to improve this situation. In today’s wide-ranging conversation, Carl and Rob also cover:

- A few reasons Carl isn’t excited by ‘strong longtermism’

- How x-risk reduction compares to GiveWell recommendations

- Solutions for asteroids, comets, supervolcanoes, nuclear war, pandemics, and climate change

- The history of bioweapons

- Whether gain-of-function research is justifiable

- Successes and failures around COVID-19

- The history of existential risk

- And much more

Get this episode by subscribing to our podcast on the world’s most pressing problems and how to solve them: type 80,000 Hours into your podcasting app. Or read the transcript below.

Producer: Keiran Harris

Audio mastering: Ben Cordell

Transcriptions: Katy Moore

Highlights

International programs to stop asteroids and comets

Carl Shulman: So in earlier decades there had been a lot of interest in the Cretaceous extinction that laid waste to the dinosaurs and most of the large land animals. And prior to this it had become clear from finding in Mexico the actual site of the asteroid that hit there, which helped to exclude other stories like volcanism.

Carl Shulman: And so it had become especially prominent and more solid that, yeah, this is a thing that happened. It was the actual cause of one of the most famous of all extinctions because dinosaurs are very personable. Young children love dinosaurs. And yeah, and then this was combined with astronomy having quite accurate information about the distribution of asteroid impacts. You can look at the moon and see craters of different sizes layered on top of one another. And so you can get a pretty good idea about how likely the thing is to happen.

Carl Shulman: And when you do those calculations, you find, well, on average you’d expect about one in a million centuries there would be a dinosaur killer–scale asteroid impact. And if you ask, “Well, how bad would it be if our civilization was laid waste by an asteroid?” Then you can say, well it’s probably worth more than one year of GDP… Maybe it’s worth 25 years of GDP! In which case we could say, yeah, you’re getting to several quadrillion dollars. That is several thousand trillion dollars.

Carl Shulman: And so the cost benefit works out just fine in terms of just saving American lives at the rates you would, say, arrange highway construction to reduce road accidents. So one can make that case.

Carl Shulman: And then this was bolstered by a lot of political attention that Hollywood helped with. So there were several films — Deep Impact and Armageddon were two of the more influential — that helped to draw the thing more into the popular culture.

Carl Shulman: And then the final blow, or actually several blows, the Shoemaker-Levy Comet impacting Jupiter and tearing Earth-sized holes in the atmosphere of Jupiter, which sort of provided maybe even more salience and visibility. And then when the ask was, we need some tens of millions, going up to $100 million dollars to take our existing telescope assets and space assets and search the sky to find any large asteroid on an impact course in the next century. And then if you had found that, then you would mobilize all of society to stop it and it’s likely that would be successful.

Carl Shulman: And so, yeah, given that ask and given the strong arguments they could make, they could say the science is solid and it was something the general public understood. Then appropriators were willing to put cost on the order of $100 million dollars and basically solve this problem for the next century. And they found, indeed, there are no asteroids on that collision course. And if they had, then we would have mobilized our whole society to stop it.

How x-risk reduction compares to GiveWell recommendations

Carl Shulman: Yeah, I think that’s a higher bar. And the main reason is that governments’ willingness to spend tends to be related to their national resources. So the US is willing to spend these enormous amounts to save the life of one American. And in fact, in a country with lower income, there are basic public health gains, things like malaria bed nets or vaccinations that are not fully distributed. So by adopting the cosmopolitan perspective, you then ask not what is the cost relative to the willingness to pay, but rather anywhere in the world where the person who would benefit the most in terms of happiness or other sorts of wellbeing or benefit. And because there are these large gaps in income, there’s a standard that would be a couple of orders of magnitude higher.

Carl Shulman: Now that cuts both ways to some extent. So a problem that affects countries that have a lot of money can be easier to advocate for. So if you’re trying to advocate for increased foreign aid, trying to advocate for preventing another COVID-19, then for the former, you have to convince decision-makers, particularly at the government level, you have to convince countries you should sacrifice more for the benefit of others. In aggregate, foreign aid budgets are far too small. They’re well under 1%, and the amount that’s really directed towards humanitarian benefit and not tied into geopolitical security ambitions and the like is limited. So you may be able to get some additional leverage if you can tap these resources from the market from existing wealthy states, but on the whole, I’m going to expect that you’re going to wind up with many times difference, and looking at GiveWell’s numbers, they suggest… I mean, it’s more like $5,000 to do the equivalent of saving a life, so obviously you can get very different results if you use a value per life saved that’s $5,000 versus a million.

Rob Wiblin: Okay, so for those reasons, it’s an awful lot cheaper potentially to save a life in an extremely poor country, and I suppose also if you just look for… not for the marginal spend to save a life in the US, but an exceptionally unusually cheap opportunity to save a life in what are usually quite poor countries. So you’ve got quite a big multiple between, I guess, something like $4 million and something like $5,000. But then if the comparison is the $5,000 to save a life figure, then would someone be especially excited about that versus the existential risk reduction, or does the existential risk reduction still win out? Or do you end up thinking that both of these are really good opportunities and it’s a bit of a close call?

Carl Shulman: So I’d say it’s going to depend on where we are in terms of our activity on each of these and the particular empirical estimates. So a thing that’s distinctive about the opportunities for reducing catastrophic risks or existential risks is that they’re shockingly neglected. So in aggregate you do have billions of dollars of biomedical research, but the share of that going to avert these sort of catastrophic pandemics is very limited. If you take a step further back to things like advocacy or leverage science, that is, picking the best opportunities within that space, that’s even more narrow.

Carl Shulman: And if you further consider… So in the area of pandemics and biosecurity, the focus of a lot of effective altruist activity around biosecurity is things that would also work for engineered pandemics. And if you buy, say, Toby Ord’s estimates, then the risk from artificial pandemics is substantially greater than the natural pandemics. The reason being that a severe engineered pandemic or series thereof — that is, like a war fought, among other things, with bioweapon WMD — could have damage that’s more like half or more of the global population. I mean, so far excess deaths are approaching one in 1,000 from COVID-19. So the scale there is larger.

Carl Shulman: And if we put all these things together and I look at the marginal opportunities that people are considering in biosecurity and pandemic preparedness, and in some of the things with respect to risk from artificial intelligence, and then also from some of the most leveraged things to reduce the damage from nuclear winter — which is not nearly as high an existential risk, but has a global catastrophic risk, a risk of killing billions of people — I think there are things that offer opportunities that are substantially better than the GiveWell top charities right now.

What would actually lead to policy changes

Rob Wiblin: It seems like if we can just argue that on practical terms, given the values that people already have, it’ll be justified to spend far more reducing existential risk, then maybe that’s an easier sell to people, and maybe that really is the crux of the disagreement that we have with mainstream views, rather than any philosophical difference.

Carl Shulman: Yeah, so I’d say… I think that’s very important. It’s maybe more central than some would highlight it as. And particularly, if you say… Take, again, I keep tapping Toby’s book because it does more than most to really lay out things with a clear taxonomy and is concrete about its predictions. So he gives this risk of one in six over the next 100 years, and 10 out of those 16 percentage points or so he assigns to risk from advanced artificial intelligence. And that’s even conditioning on only a 50% credence in such AI capabilities being achieved over the century. So that’s certainly not a view that is widely, publicly, clearly held. There are more people who hold that view than say it, but that’s still a major controversial view, and a lot of updates would follow from that. So if you just take that one issue right there, the risk estimates on a lot of these things move drastically with it.

Carl Shulman: And then the next largest known destruction risk that he highlights is risks from engineered pandemics and bioweapons. And there, in some ways we have a better understanding of that, but there’s still a lot of controversy and a lot of uncertainty about questions like, “Are there still secret bioweapons programs as there were in the past? How large might they be? How is the technology going to enable damaging attacks versus defenses?” I mean, I think COVID-19 has showed a lot of damage can still be inflicted, but also they’re very hard to cause extinction because we can change our behavior a lot, we can restrict spread.

Carl Shulman: But still, there’s a lot of areas of disagreement and uncertainty here in biosafety and future pandemics. And you can see that in some of the debates about gain of function research in the last decade, where the aim was to gain incremental knowledge to better understand potentially dangerous pathogens. And in particular, the controversial experiments were those that were altering some of those pathogens to make them more closely resemble a thing that could cause global pandemics. Or that might be demonstrating new mechanisms to make something deadly, or that might be used, say, in biological weapons.

Carl Shulman: So when the methods of destruction are published, and the genomes of old viruses are published, they’re then available to bioweapons programmes and non-state actors. And so some of the players arguing in those debates seem to take a position that there’s basically almost no risk of that kind of information being misused. So implicitly assigning really low probability to future bioterrorism or benefiting some state bioweapons programmes, while others seem to think it’s a lot more likely than that. And similarly, on the risk of accidental release, you’ve had people like Marc Lipsitch, arguing for using estimates based off of past releases from known labs, and from Western and other data. And then you had other people saying that their estimates were overstating the risk of an accidental lab escape by orders and orders of magnitude to a degree which I think is hard to reconcile with the number of actual leaks that have happened. But yeah, so if you were to sync up on those questions, like just what’s the right order of magnitude of the risk of information being used for bioweapons? What’s the right order of magnitude of escape risk of different organisms? It seems like that would have quite a big impact on policy relative to where we stand today.

Solutions for climate change

Carl Shulman: So I’d say that what you want to do is find things that are unusually leveraged, that are taking advantage of things, like attending to things that are less politically salient, engaging in scientific and technological research that doesn’t deliver as immediate of a result. Things like political advocacy, where you’re hoping to leverage the resources of governments that are more flush and capable.

Carl Shulman: Yeah, so in that space, clean energy research and advocacy for clean energy research seems relatively strong. Some people in the effective altruism community have looked into that and raised funds for some work in that area. I think Bill Gates… The logic for that is that if you have some small country and they reduce their carbon emissions by 100%, then that’s all they can do, costs a fair amount, and it doesn’t do much to stop emissions elsewhere, for example, in China and India and places that are developing and have a lot of demand for energy. And if anything, it may… If you don’t consume some fossil fuels, then those fossil fuels can be sold elsewhere.

Carl Shulman: Whereas if you develop clean energy tech, that changes the decision calculus all around the world. If solar is cheaper than coal — and it’s already making great progress over much of the world — and then hopefully with time, natural gas, then it greatly alleviates the difficulty of the coordination problem. It makes the sacrifice needed to do it less. And if you just look at how little is actually spent on clean energy research compared to the benefits and compared to the successes that have already been achieved, that looks really good. So if I was spending the incremental dollar on reducing climate change, I’d probably want to put it more towards clean energy research than immediate reductions of other sorts, things like planting trees or improving efficiency in a particular building. I more want to solve that global public goods problem of creating the technologies that will better solve things.

Carl Shulman: So continuing progress on solar, on storage, you want high-voltage transmission lines to better integrate renewables. On nuclear, nuclear has enormous potential. And if you look at the cost for France to build an electrical grid based almost entirely on nuclear, way back early in the nuclear era, it was quite manageable. In that sense, for electrical energy, the climate change problem is potentially already solved, except that the regulatory burdens on nuclear are so severe that it’s actually not affordable to construct new plants in many places. And they’re held to standards of safety that are orders of magnitude higher than polluting fossil fuels. So enormous numbers of people are killed, even setting aside climate change, just by particulate matter and other pollution from coal, and to a lesser extent, natural gas.

Carl Shulman: But for the major nuclear accidents, you have things like Fukushima, where the fatalities from the Fukushima release seem to be zero, except for all the people who were killed panicking about the thing due to exaggerated fears about the damage of small radiation levels. And we see large inconsistencies in how people treat radiation levels from different sources versus… You have more radiation when you are at a higher altitude, but we panic many orders and orders of magnitude less about that sort of thing. And the safety standards in the US basically require as safe as possible, and they don’t stop at a level of safer than all the alternatives or much better.

Carl Shulman: So we’re left in a world where nuclear energy could be providing us with largely carbon-free power, and converted into other things. And inventing better technologies for it could help, but given the regulatory regime, it seems like they would again have their costs driven up accordingly. So if you’re going to try and solve nuclear to fight climate change, I would see the solution as more on the regulatory side and finding ways to get public opinion and anti-nuclear activist groups to shift towards a more pro-climate, pro-nuclear stance.

Solutions for nuclear weapons

Carl Shulman: I found three things that really seemed to pass the bar of “this looks like something that should be in the broad EA portfolio” because it’s leveraged enough to help on the nuclear front.

Carl Shulman: The first one is better characterizing the situation with respect to nuclear winter. And so a relatively small number of people had done work on that. Not much followup in subsequent periods. Some of the original authors did do a resurgence over the last few decades, writing some papers using modern climate models, which have been developed a lot because of concern about climate change and just general technological advance to try and refine those. Open Philanthropy has provided grants funding some of that followup work and so better assessing the magnitude of the risk, how likely nuclear winter is from different situations, and estimating the damages more precisely.

Carl Shulman: It’s useful in two ways. First, the magnitude of the risk is like an input for folk like effective altruists to decide how much effort to put into different problems and interventions. And then secondly, better clarifying the empirical situation can be something that can help pull people back from the nuclear brink.

Carl Shulman: [The second is] just the sociopolitical aspects of nuclear risk estimation. How likely is it from the data that we have that things escalate? And so there are the known near misses that I’m sure have been talked about on the show before. Things like the Cuban Missile Crisis, Able Archer in the 80s, but we have uncertainty about what would have been the next step if things had changed in those situations? How likely was the alternative? The possibility that this sub that surfaced in response to depth charges in the Cuban Missile Crisis might’ve instead fired its weapons.

Carl Shulman: And so, we don’t know though. Both Kennedy and Khrushchev, insofar as we have autobiographical evidence, and of course they might lie for various reasons and for their reputation, but they said they were really committed to not having a nuclear war then. And when they estimated and worried that it is like a one in two, one in three chance of disaster, they were also acting with uncertainty about the thinking of their counterparts.

Carl Shulman: We do have still a fairly profound residual uncertainty about the likelihood of escalating from the sort of triggers and near misses that we see. We don’t know really how near they are because of the difficulty in estimating these remaining things. And so I’m interested in work that better characterizes those sorts of processes and the psychology and what we can learn from as much data as exists.

Carl Shulman: Number three… so, the damage from nuclear winter on neutral countries is anticipated to be mostly by way of making it hard to grow crops. And all the analyses I’ve seen and talking to the authors of the nuclear winter papers suggest there’s not a collapse so severe that no humans could survive. And so there would be areas far from the equator, New Zealand might do relatively well. Fishing would be possible. I think you’ve had David Denkenberger on the show.

Carl Shulman:

So I can refer to that. And so that’s something that I came across independently relatively early on when I was doing my systematic search through what are all of the x-risks? What are the sort of things we could do to respond to each of them? And I think that’s an important area. I think it’s a lot more important in terms of saving the lives of people around today than it is for existential risk. Because as I said, sort of directly starving everyone is not so likely but killing billions seems quite likely. And even if the world is substantially able to respond by producing alternative foods, things like converting biomass into food stocks, that may not be universally available. And so poor countries might not get access if the richest countries that have more industrial capacity are barely feeding themselves. And so the chance of billions dying from such a nuclear winter is many times greater than that of extinction directly through that mechanism.

Gain-of-function research

Carl Shulman: So, the safety still seems poor, and it’s not something that has gone away in the last decade or two. There’ve been a number of mishaps. Just in recent years, for example, those multiple releases of, or infections of SARS-1 after it had been extirpated in the wild. Yeah, I mean, the danger from that sort of work in total is limited by the small number of labs that are doing it, and even those labs most of the time aren’t doing it. So, I’m less worried that there will be just absolutely enormous quantities of civilian research making ultra-deadly pandemics than I would about bioweapons programs. But it does highlight some of the issues in an interesting way.

Carl Shulman: And yeah, if we have an infection rate of one in 100 per worker year, or one in 500 per laboratory year, and given an infection of a new pandemic thing. And a lot of these leaks, yeah, like someone else was infected. Usually not many because they don’t have high enough R naught. So yeah, you might say on the order of one in 1,000 per year of work with this kind of thing for an escape, and then there’s only a handful of effective labs doing this kind of thing.

Carl Shulman: So, you wouldn’t have expected any catastrophic releases to have happened yet reliably, but also if you scale this up and had hundreds of labs doing pandemic pathogen gain-of-function kind of work, where they were actually making things that would themselves be ready to cause a pandemic directly, yeah, I mean that cumulative threat could get pretty high…

Carl Shulman: So I mean, take it down to a one in 10,000 leak risk and then, yeah, looking at COVID has an order of magnitude for damages. So, $10 trillion, several million dead, maybe getting around 10 million excess dead. And you know, of course these things could be worse, you could have something that did 50 or 100 times as much damage as COVID, but yeah, so 1/10,000ths of a $10 trillion burden or 10 million lives, a billion dollars, 1,000 dead, that’s quite significant. And if you… You could imagine that these labs had to get insurance, in the way that if you’re going to drive a vehicle where you might kill someone, you’re required to have insurance so that you can pay to compensate for the damage. And so if you did that, then you might need a billion dollars a year of insurance for one of these labs.

Carl Shulman: And now, there’s benefits to the research that they do. They haven’t been particularly helpful in this pandemic, and critics argue that this is a very small portion of all of the work that can contribute to pandemic response and so it’s not particularly beneficial. I think there’s a lot to that, but regardless of that, it seems like there’s no way that you would get more defense against future pandemics by doing one of these gain-of-function experiments that required a billion dollars of insurance, than you would by putting a billion dollars into research that doesn’t endanger the lives of innocent people all around the world.

Rob Wiblin: Something like funding vaccine research?

Carl Shulman: Yeah. It would let you do a lot of things to really improve our pandemic forecasting response, therapeutics, vaccines. And so, it’s hard to tell a story where this is justified. And it seems that you have an institutional flaw where people approve these studies and then they maybe put in millions of dollars of grant money into them, and they wouldn’t approve them if they had to put in a billion dollars to cover the harm they’re doing to outside people. But then currently, our system doesn’t actually impose appropriate liability or responsibility, or anything, for those kinds of impacts on third parties. There’s a lot of rules and regulations and safety requirements, and duties to pay settlements to workers who are injured in the lab, but there’s no expectation of responsibility for the rest of the world. Even if there were, it would be limited because it’d be a Pascal’s wager sort of thing, that if you’re talking about a one in 1,000 risk, well, you’d be bankrupt.

Carl Shulman: Maybe the US government could handle it, but the individual decision-makers, it’s just very unlikely to come up in their tenure or from, certainly from a particular grant or a particular study. It’s like if there were some kinds of scientific experiments that emitted massive, massive amounts of pollution and that pollution was not considered at all in whether to approve the experiments, you’d wind up getting a lot too many of those experiments completed, even if there were some that were worth doing at that incredible price.

Suspicious convergence around x-risk reduction

Rob Wiblin: You want to say that even if you don’t care much about [the long-term future], you should view almost the same activities, quite similar activities, as nonetheless among the most pressing things that anyone could do… And whenever one notices a convergence like that, you have to wonder, is it not perhaps the case that we’ve become really attached to existential risk reduction as a project? And now we’re maybe just rationalizing the idea that it has to be the most important?

Carl Shulman: Yeah. Well, the first and most important thing is I’m not claiming that at the limit, you get, exactly the same things are optimal by all of these different standards. I’d say that the two biggest factors are first, that if all you’re adjusting are something like population ethics, while holding fixed things like being willing to take risks on low probability things, using quantitative evidence, having the best picture of what’s happening with future technologies, all of that, then you’re sharing so much that you’re already moving away from the standard practice a lot. And yeah, winding up in this narrow space. And then second, is just, if it’s true that in fact the world is going to be revolutionized and potentially ruined by disasters involving some of these advanced technologies over the century, then that’s just an enormous, enormous thing. And you may take different angles on how to engage with that depending on other considerations and values.

Carl Shulman: But the thing itself is so big and such an update that you should be taking some angle on that problem. And you can analogize. So say you’re Elon Musk and Musk cares about climate change and AI risk and other threats to the future of humanity. And he’s putting most of his time in Tesla. And you might think that AI poses a greater risk of human extinction over the century. But if you have a plan to make self-driving electric cars that will be self-financing and make you the richest person in the world, which will then let you fund a variety of other things. It could be a great idea if Elon Musk wanted to promote, you know, the fine arts. Because being the richest person in the world is going to set you up relatively well for that. And so similarly, if indeed AI is set to be one of the biggest things ever, in this century, and to both set the fate of existing beings and set the fate of the long-term future of Earth-originating civilization, then it’s so big that you’re going to take some angle on it.

Carl Shulman: And different values may lead you to focus on different aspects of the problem. If you think, well, other people are more concerned about this aspect of it. And so maybe I’ll focus more on the things that could impact existing humans, or I’ll focus more on how AI interacts with my religion or national values or something like that. But yeah, if you buy these extraordinary premises about AI succeeding at its ambitions as a field, then it’s so huge that you’re going to engage with it in some way.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. Okay. So even though you might have different moral values, just the empirical claims about the impact that these technologies might have potentially in the next couple of decades, setting aside anything about future generations, future centuries. That’s already going to give you a very compelling drive, almost no matter what your values are, to pay attention to that and what impact it might have.

Carl Shulman: Although that is dependent on the current state of neglectedness. If you expand activities in the neglected area, by tenfold, a hundredfold, a thousandfold, then its relative attractiveness compared to neglected opportunities in other areas will plummet. And so I would not expect this to continue if we scaled up to the level of investment in existential risk reduction that, say, Toby Ord talks about. And then you would wind up with other things that maybe were exploiting a lot of the same advantages. Things like taking risks, looking at science, et cetera, but in other areas. Maybe really, really super leverage things in political advocacy for the right kind of science, or maybe use of AI technologies to help benefit the global poor today, or things like that.

Articles, books, and other media discussed in the show

Carl’s work

- Reflective Disequilibrium by Carl Shulman, including posts on:

- Sharing the World with Digital Minds by Carl Shulman and Nick Bostrom

Books

- The Precipice: Existential Risk and the Future of Humanity by Toby Ord

- The Doomsday Machine: Confessions of a Nuclear War Planner by Daniel Ellsberg

- Democracy for Realists: Why Elections Do Not Produce Responsive Government by Christopher H. Achen and Larry M. Bartels

Articles

- Are We Living at the Hinge of History? by William MacAskill

- The Past and Future of Economic Growth: A Semi-Endogenous Perspective by Chad I. Jones

- The End of Economic Growth? Unintended Consequences of a Declining Population by Chad I. Jones

- Human error in high-biocontainment labs: a likely pandemic threat by Lynn Klotz

- Moratorium on Research Intended To Create Novel Potential Pandemic Pathogens by Marc Lipsitch and Thomas V. Inglesby

- Learning to summarize from human feedback by Nisan Stiennon, et al.

Job opportunities

80,000 Hours articles and episodes

- We could feed all 8 billion people through a nuclear winter. Dr David Denkenberger is working to make it practical

- Mark Lynas on climate change, societal collapse & nuclear energy

- Andy Weber on rendering bioweapons obsolete and ending the new nuclear arms race

- Dr Owen Cotton-Barratt on why daring scientists should have to get liability insurance

- If you care about social impact, why is voting important?

Everything else

- Draft report on AI timelines by Ajeya Cotra

- What should we learn from past AI forecasts? by Luke Muehlhauser

- Clean Energy Innovation Policy by Let’s Fund

- Why are nuclear plants so expensive? Safety’s only part of the story by John Timmer

- Did Pox Virus Research Put Potential Profits Ahead of Public Safety? by Nell Greenfieldboyce

- Pedestrian Observations: Why American Costs Are So High by Alon Levy

- Wally Thurman on Bees, Beekeeping, and Coase on with Russ Roberts on EconTalk

Transcript

Table of Contents

- 1 Rob’s intro [00:00:00]

- 2 The interview begins [00:01:34]

- 3 A few reasons Carl isn’t excited by strong longtermism [00:03:47]

- 4 Longtermism isn’t necessary for wanting to reduce big x-risks [00:08:21]

- 5 Why we don’t adequately prepare for disasters [00:11:16]

- 6 International programs to stop asteroids and comets [00:18:55]

- 7 Costs and political incentives around COVID [00:23:52]

- 8 How x-risk reduction compares to GiveWell recommendations [00:34:34]

- 9 Solutions for asteroids, comets, and supervolcanoes [00:50:22]

- 10 Solutions for climate change [00:54:15]

- 11 Solutions for nuclear weapons [01:02:18]

- 12 The history of bioweapons [01:22:41]

- 13 Gain-of-function research [01:34:22]

- 14 Solutions for bioweapons and natural pandemics [01:45:31]

- 15 Successes and failures around COVID-19 [01:58:26]

- 16 Who to trust going forward [02:09:09]

- 17 The history of existential risk [02:15:07]

- 18 The most compelling risks [02:24:59]

- 19 False alarms about big risks in the past [02:34:22]

- 20 Suspicious convergence around x-risk reduction [02:49:31]

- 21 How hard it would be to convince governments [02:57:59]

- 22 Defensive epistemology [03:04:34]

- 23 Hinge of history debate [03:16:01]

- 24 Technological progress can’t keep up for long [03:21:51]

- 25 Strongest argument against this being a really pivotal time [03:37:29]

- 26 How Carl unwinds [03:45:30]

- 27 Rob’s outro [03:48:02]

Rob’s intro [00:00:00]

Rob Wiblin: Hi listeners, this is the 80,000 Hours Podcast, where we have unusually in-depth conversations about the world’s most pressing problems, what you can do to solve them, and why you have to be really sure to fit your air filters the right way around if you work at a bioweapons lab. I’m Rob Wiblin, Head of Research at 80,000 Hours.

You might not have heard of today’s guest, Carl Shulman, but he’s a legend among professional existential risk and effective altruist researchers.

This is the first long interview Carl has ever given, not that you’d ever be able to tell.

In this episode Carl makes the case that trying to tackle global catastrophic risks like AI, pandemics and nuclear war is common sense and doesn’t rest on any unusual philosophical views at all. In fact it passes the same boring cost-benefit analyses society uses to build bridges and run schools with flying colours, even if you only think about this generation.

Carl has spent decades reading deeply about these issues and trying to forecast how the future is going to play out, so we then turn to technical details and historical analogies that can help us predict how probable and severe various different threats are — and what specifically should be done to safeguard humanity through a treacherous period.

This is a long conversation so you might like to check the chapter listings, if your podcasting app supports them. Some sections you might be particularly interested in have titles like:

- False alarms about big risks in the past

- Solutions for climate change

- Defensive epistemology and

- Strongest argument against this being a really pivotal time

If you like this episode tell a friend about the show. You can email us ideas and feedback at podcast at 80000hours dot org.

Without further ado I bring you Carl Shulman.

The interview begins [00:01:34]

Rob Wiblin: Today I’m speaking with Carl Shulman. Carl studied philosophy at the University of Toronto and Harvard University and then law at NYU. Since 2012 he’s been a research associate at Oxford University’s Future of Humanity Institute, where he’s published on risks from AI as well as decision theory. He consults for the Open Philanthropy Project among other organizations and blogs at Reflective Disequilibrium.

Rob Wiblin: While he keeps a low profile, Carl has had as much influence on the conversation about existential risks as anyone and he’s also just one of the most broadly knowledgeable people that I know. So, thanks for coming on the podcast, Carl.

Carl Shulman: Thanks, Rob. It’s a pleasure. I’m a listener as well.

Rob Wiblin: I hope we’ll get to talk about reasons that you’re skeptical of strong longtermism as a philosophical position, but why you nevertheless focus a lot of your work on preventing existential risks. But first, what are you working on at the moment and why do you think it’s important?

Carl Shulman: Yeah, right now the two biggest projects I’m focusing on are, one, some work with the Open Philanthropy Project on modeling the economics of advanced AI. And then, at the Future of Humanity Institute I’m working with Nick Bostrom on a project on the political and moral status of digital minds; that is, artificial intelligence systems that are potentially deserving of moral status and how we might have a society that integrates both humans and such minds.

Rob Wiblin: Nice. Yeah, I saw you had a publication with Nick Bostrom about that last year. I haven’t had a chance to read it yet. I think Bostrom just announced on his website that he’s thinking of writing a book about this question of how do you integrate potentially morally valuable digital minds into society.

Carl Shulman: Yes, we’ve been working on this book project for a while and that OUP book chapter spun out of that, Sharing the World with Digital Minds. The central theme of that paper is largely that on a lot of different accounts of wellbeing, digital minds in one way or another could be more efficient than human beings. So, that is, for a given quantity of material resources they could have a lot more wellbeing come out of that. And then, that has implications about how coexistence might work under different moral counts.

Rob Wiblin: Nice. Yeah, maybe we’ll get a chance to talk about that later on in the conversation.

A few reasons Carl isn’t excited by strong longtermism [00:03:47]

Rob Wiblin: But yeah first off, as a preface to the body of the conversation, I’d like to kind of briefly get a description of your, as I understand it, lukewarm views about strong longtermism.

Rob Wiblin: And I guess strong longtermism is, broadly speaking, the view that the primary determinant of the kind of moral value of our actions is how those actions affect the very long-term future. Which, I guess, is like more than 100 years, maybe more than 1,000 years, something like that. What’s the key reason you’re reluctant to fully embrace strong longtermism?

Carl Shulman: Yeah. Well, I think I should first clarify that I’m more into efforts to preserve and improve the long-term future than probably 99% of people. I’d say that I would fit with my colleague Toby Ord’s description in his book The Precipice in thinking that preventing existential risk is one of the great moral issues of our time. Depending on how the empirics work out, it may even be the leading moral issue of our time. But I certainly am not going to say it is the only issue or to endorse a very, sort of, strong longtermist view that, say, even a modest increment to existential risk reduction would utterly overwhelm considerations on other perspectives.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. Yeah, I suppose a lot of your philosophy colleagues or people at the Future of Humanity Institute are maybe more open to the idea that the long-term future is really dominant. Is there any kind of way of describing perhaps why you part ways with them on that?

Carl Shulman: Yeah, I mean, I think the biggest reason is that there are other normative perspectives that place a lot of value on other considerations. So, some examples: duties of justice where if you owe something in particular, say, to people that you have harmed or if you owe duties of reciprocity to those who have helped you or to keep a promise, that sort of thing. Filial piety — when you have particular duties to your parents or to your children.

Carl Shulman: And if we give these sorts of other views that would not embrace the sort of most fanatical versions of longtermism, and we say they’re going to have some say, then insofar as they’re going to have some say in our decisions, some weight on our behavior, then that’s inevitably going to lead to some large ratios.

Carl Shulman: If you ever do something out of duty to someone you’ve harmed or you ever do something on behalf of your family, then there’s a sense in which you’re trading off against some vast potential long-term impact. It seems like the normative strength of the case for longtermism is not so overwhelming as to say all of these things would be wiped out.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. So, I guess, some people, maybe they try to get all of the different kind of moral considerations or the different theories that they place some weight on, and then compare them all on the same scale, like a possible scale being how much wellbeing did you create?

Rob Wiblin: Whereas I guess you’re thinking that your kind of moral reasoning approach takes different moral theories or different moral considerations and then slightly cordons them off and doesn’t want to put them on a single scale from like zero to a very large number, where like one theory that values one particular thing could end up completely swamping the other, because it seems like you have a really good opportunity within that area. It’s maybe like there’s buckets that do have some flexibility between moving your effort between them, but you’re not going to let any one moral concern that you have just get all of the resources.

Carl Shulman: Yeah. And the literature on moral uncertainty talks about some of the challenges to, say, interconvert. It’s filial piety really, utilitarianism, but with a different weight for your family, or does it conceptualize the world differently. And it’s more about obligations of you as an agent or think about it as like the strength of different moral sentiments. And so there are places where each of those approaches seem to have advantages.

Carl Shulman: But in general, if you’re trying to make an argument to say that A is a million times as important as B, then any sort of hole in that argument can really undermine it. Because if you mix in, if you say, well, A is a million times better on this dimension, but if you mix even a little probability or modest mixture of, well, actually this other thing that B is better on dominates, then the argument is going to be quickly attenuated.

Rob Wiblin: Oh yeah. I guess the ratio can’t end up being nearly so extreme.

Carl Shulman: Yeah. And I think this is, for example, what goes wrong in a lot of people’s engagement with the hypothetical of Pascal’s mugging.

Longtermism isn’t necessary for wanting to reduce big x-risks [00:08:21]

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. Okay. Yeah. There’s a whole big debate that we could have here. And we might return to some of this moral philosophy later on. But talking about this too much might be a little bit ironic because kind of a key view of yours, which we’re hopefully going to explore now, is that a lot of these kind of moral philosophy issues matter a lot less in determining what people ought to do than perhaps is commonly supposed and perhaps matter less relative to the amount of attention that they’ve gotten on this podcast, among other places.

Rob Wiblin: So yeah, basically as I understand it, you kind of believe that most of the things that the effective altruism or longtermism communities are doing to reduce risks of catastrophic disaster can basically be justified on really mundane cost-benefit analysis that doesn’t have to place any special or unusual value on the long-term future.

Rob Wiblin: I guess the key argument is just that the probability of a disaster that kills a lot of people, most of the people who are alive today, that that risk is just alarmingly high and that it could be reduced at an acceptable cost. And I recently saw you give a talk where you put some numbers on this.

Rob Wiblin: And I guess, in brief the argument runs, kind of, the US government in terms of its regulatory evaluations is willing to pay up to something like $4 million to save the life of an American. I think it varies depending on the exact government agency, but that’s in the ballpark, which then means that saving all US lives at any given point in time would be worth $1,300 trillion. So an awful lot of money.

Rob Wiblin: And then, if you did believe that the risk of human extinction over the next 50 or 100 years is something like one in six as Toby Ord suggests is a reasonable figure in his book The Precipice, and you think you could reduce that by just 1%, so 1% of that one-sixth, then that would be worth spending up to $2.2 trillion for the US government to achieve just in terms of the American lives that would be saved.

Rob Wiblin: And I guess you think it would cost a lot less than that to achieve that level of risk reduction if the money was spent intelligently. So it just simply passes a government cost-benefit test with flying colors, with like a very big benefit-to-cost ratio. Yeah, what do you think is the most important reason that this line, this very natural line of thinking, hasn’t already motivated a lot more spending on existential risk reduction?

Carl Shulman: Yeah, so just this past year or so we’ve had a great illustration of these dynamics with COVID-19. Now, natural pandemics have long been in the parade of global catastrophic risk horribles and the risk is relatively well understood. There’ve been numerous historical pandemics. The biggest recent one was the 1918, 1919 influenza, which killed tens of millions of people in a world with a smaller population.

Carl Shulman: And so I think we can look at what are all of the reasons why the COVID-19 pandemic, which now costs on the order of $10 trillion, excess mortality is approaching 10 million. What are all the reasons why we didn’t adequately prepare for that? And I think a lot of that is going to generalize to engineered pandemics, to risks from advanced artificial intelligence, and so on.

Why we don’t adequately prepare for disasters [00:11:16]

Rob Wiblin: Okay. Yeah. So maybe let’s go one by one, like what’s a key reason or maybe the most significant reason in your mind for why we didn’t adequately prepare for COVID-19?

Carl Shulman: Yeah, so I’d say that the barriers were more about political salience and coordination across time and space. So there are examples where risks that are even much less likely have become politically salient and there’s been effort mobilized to stop them. Asteroid risk would fall into that category. But yeah, the mobilization for pandemics, that has not attained that same sort of salience and the measures for it being more expensive than the measures to stop asteroids.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. So do you think, like it’s primarily driven by the idea that, so just normal people like me or normal voters in the electorate, there’s only so many things that we can think about at once. And we only have so much time to think about politics and society as a whole. And that means that we tend to get buffeted around by kind of what’s in the news, like what’s a topical risk or problem to think about now?

Rob Wiblin: That means it’s very easy for regular periodic risk like a major pandemic to just kind of fall off of the agenda. And then it’s not salient to voters. And so as a result, politicians and bureaucrats don’t really see it as in their personal or career advantage to try to prepare for something that they might be blamed for just wasting money, because it’s not really a thing that people especially are talking about.

Carl Shulman: Yeah, I think there’s a lot of empirical evidence on these political dynamics. There’s a great book called Democracy for Realists that explores a lot of this empirical literature. And so you see things that like, after a flood or other natural disaster, there’s a spike in enthusiasm for spending to avert it. But it’s not as though right after one flood or hurricane the chances of another are greatly elevated. It’s a random draw from the distribution, but like people remember it having just happened.

Carl Shulman: And right now in the wake of COVID there’s a surge of various kinds of biomedical and biosecurity spending. And so we’ll probably move somewhat more towards a rational level of countermeasures. Though, I think, still we look set to fall far short as we have during the actual pandemic. And so you’ve got the dynamics of that sort.

Carl Shulman: And you see that likewise with economic activity. So voters care about how the economy is doing, but they’re much more influenced by the economy in the few months right before the election. And so even if there’ve been four years of lesser economic growth, it makes sense for politicians to throw out things like sudden increases and checks; one-time expenditures cause monetary policy to differentially favor economic activity right around there.

Carl Shulman: And so, yeah, so ultimately it’s difficult for the average voter to estimate and understand how large these respective risks are. Generally a poor grip there. They don’t naturally create strong incentives in advance for politicians to deal with it because it’s not on their minds. And then you can get some reaction right after an event happens, which may be too late. And it doesn’t last well enough.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. Yeah. Okay. So that’s one broad category of why we failed to prepare sufficiently for COVID-19 and I guess probably why we failed to prepare adequately for other similar periodic disasters. Yeah. Is there any other kind of broad category that’s important that people should have in mind?

Carl Shulman: Certainly there’s the obvious collective action problems. These come up a lot with respect to climate change. So the carbon emissions of any given country and certainly any individual disperse globally. And so if you as an individual are not regulated in what you do, you emit some carbon to do something that’s useful to you and you bear, depending on your income and whatnot, on the order of one in a billion, one in 10 billion, of the cost that you’re imposing on the world.

Carl Shulman: And that’s certainly true for pandemics. So a global pandemic imposes a risk on everyone. And if you invest in countermeasures and then you’re not going to be able to recover those costs later, then yeah, that makes things more challenging.

Carl Shulman: You might think this is not that bad because there are a few large countries. So the US or China, you’re looking at like order of one-sixth of the world economy. So maybe they only have a factor of six, but then within countries you similarly have a lot of internal coordination problems.

Carl Shulman: So if politicians cause a sacrifice now and most of the benefits are for future — leave generations aside, we can always talk about caring about future generations — I would like politicians to care about, like the next electoral cycle. And so, yeah, so they’re generally focused on winning their next election. And then it’s made worse by the fact that as you go forward, the person in charge may be your political opponent.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. So anything you do to prepare for a pandemic that happens to fall during your opponent’s term is, is bad from your point of view or bad from this like narrow, selfish point of view.

Carl Shulman: Yeah. And we can see with the United States where you had a switchover of government in the midst of the pandemic and then attitudes on various policies have moved around in a partisan fashion.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. So yeah, this coordination problem seems really central in the case of climate change. Because if you’re a country that imposes a carbon tax and thereby reduces its emissions, you’ve borne almost all of the cost of that, but you only get potentially quite a small fraction of the benefit depending on how large the country is.

Rob Wiblin: With the pandemic, maybe it seems to have this effect a bit less because you can do lots of things that benefit your country at the national level, like having a sensible policy to stop people with the disease from flying in, to have stockpiles of protective equipment and so on.

Rob Wiblin: And I guess there’s also business models where you can recover a lot of your costs. So if you’re a government or a university or research group that is working on biomedical science that could be useful in a pandemic, if there is a pandemic, you can potentially recover a bunch of the costs through patents and selling that kind of stuff.

Rob Wiblin: So is that maybe why you mentioned this as like a secondary factor in the pandemic case, whereas it might be kind of more central in the climate change case?

Carl Shulman: Yeah. I mean, so again, I think you can trace a lot of what goes wrong to externalities, but they’re more at the level of political activity. So like the standard rational irrationality story. So like a typical voter, it’s extremely unlikely that they will be the deciding vote. There’s an enormous expected value because if you are the deciding vote, then it can change the whole country. And you’ve written some nice explainer articles on this.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. Yeah, I’ll stick up a link to that.

Carl Shulman: But that means there’s very little private incentive to research and understand these issues. And more of the incentive comes from things like affiliating with your team, seeming like a good person around your local subculture. And those dynamics then are not super closely attuned to what people are going to like as an actual outcome. So people will often vote for things that wind up making the country that they live in less desirable to them.

Carl Shulman: And so they would behave differently if they were deciding, “Which country should I move to because I like how things are going there?” versus “What am I going to vote on?” And then a lot of the policies that could have staunched the pandemic much earlier seem to fall into that category.

International programs to stop asteroids and comets [00:18:55]

Rob Wiblin: Interesting. Yeah. So I guess despite all of these potential pitfalls, the US has indeed run at least one pretty big program that was in large part to reduce the risk of human extinction. And that’s the famous effort by NASA I think in mostly the 90s maybe but also the 2000s to identify all the larger asteroids and comets in order to see if any of them might hit the earth at any point soon. How did that one come about?

Carl Shulman: Yeah, so this is an interesting story. So in earlier decades there had been a lot of interest in the Cretaceous extinction that laid waste to the dinosaurs and most of the large land animals. And prior to this it had become clear from finding in Mexico the actual site of the asteroid that hit there, which helped to exclude other stories like volcanism.

Carl Shulman: And so it had become especially prominent and more solid that, yeah, this is a thing that happened. It was the actual cause of one of the most famous of all extinctions because dinosaurs are very personable. Young children love dinosaurs. And yeah, and then this was combined with astronomy having quite accurate information about the distribution of asteroid impacts. You can look at the moon and see craters of different sizes layered on top of one another. And so you can get a pretty good idea about how likely the thing is to happen.

Carl Shulman: And when you do those calculations, you find, well, on average you’d expect about one in a million centuries there would be a dinosaur killer–scale asteroid impact. And if you ask, “Well, how bad would it be if our civilization was laid waste by an asteroid?” Then you can say, well it’s probably worth more than one year of GDP… Maybe it’s worth 25 years of GDP! In which case we could say, yeah, you’re getting to several quadrillion dollars. That is several thousand trillion dollars.

Carl Shulman: And so the cost benefit works out just fine in terms of just saving American lives at the rates you would, say, arrange highway construction to reduce road accidents. So one can make that case.

Carl Shulman: And then this was bolstered by a lot of political attention that Hollywood helped with. So there were several films — Deep Impact and Armageddon were two of the more influential — that helped to draw the thing more into the popular culture.

Carl Shulman: And then the final blow, or actually several blows, the Shoemaker-Levy Comet impacting Jupiter and tearing Earth-sized holes in the atmosphere of Jupiter, which sort of provided maybe even more salience and visibility. And then when the ask was, we need some tens of millions, going up to $100 million dollars to take our existing telescope assets and space assets and search the sky to find any large asteroid on an impact course in the next century. And then if you had found that, then you would mobilize all of society to stop it and it’s likely that would be successful.

Carl Shulman: And so, yeah, given that ask and given the strong arguments they could make, they could say the science is solid and it was something the general public understood. Then appropriators were willing to put cost on the order of $100 million dollars and basically solve this problem for the next century. And they found, indeed, there are no asteroids on that collision course. And if they had, then we would have mobilized our whole society to stop it.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. Nice. So I suppose, yeah, the risk was really very low, if it was one in… one in 100 million centuries, did you say?

Carl Shulman: One in a hundred million per year. One in a million per century.

Rob Wiblin: Okay, yeah. So the risk was pretty low, but I suppose like, not so low that we would want to completely ignore it. And they spent up to $100 million dollars. What does that then imply about their willingness to pay to prevent extinction with 100% probability? Does it roughly match up with the kind of 1,300 trillion number that we were talking about earlier?

Carl Shulman: Yeah, so it’s a bit tricky. So if you look to things like World War II, so in World War II the share of Japanese GDP going to the war effort went as high as 70%.

Rob Wiblin: Wow.

Carl Shulman: And that was one of the higher ones, but still across all the major combatants you had like on the order of half of all productive effort going to the war. So it was clearly possible to have massive social mobilizations and clearly the threat of being, having everyone in your country killed is even worse —

Rob Wiblin: Motivating, yeah.

Carl Shulman: — than the sort of typical result of losing a war. I mean, certainly Japan is doing pretty well despite losing World War II. And so you’d think we could have maybe this mass mobilization.

Costs and political incentives around COVID [00:23:52]

Carl Shulman: And then there’s the question though of, what do you need to trigger that? And so wars were very well understood. There was a clear process of what to do about them, but other existential risks aren’t necessarily like that. So even with COVID, so the aggregate economic cost of COVID has been estimated on the order of $10 trillion and many trillions of dollars have been spent by governments on things like stimulus payments and such to help people withstand the blow.

Carl Shulman: But then the actual expenditures on say, making the vaccines or getting adequate supplies of PPE have been puny by comparison. And so you have, I mean, there’s even been complaints about, so someone like Pfizer might make a $10 profit on a vaccine that generates more than $5,000 of value per dose. And we’re having this gradual rollout of vaccines to the world.

Carl Shulman: Those vaccines were mostly discovered at the very beginning of 2020. And so if we were having that wartime mobilization, then you’d think that all the relevant factories and the equipment that could have been converted would have been converted. And there are limits to that. It involves specialized and new technologies. But you’d think that… say you’d be willing to pay $500 instead of $50 for the vaccine or $2,000, and then make contracts such that providers who can deliver more vaccine faster get more payment, and then they can do expensive things to incrementally expedite production.

Carl Shulman: You maybe have, you know, make sure you have 24/7 working shifts. Hire everyone from related industries and switch them over. Take all of the production processes that are switchable and do them immediately. Even things like just supplying masks universally to the whole population, you do that right away.

Carl Shulman: And you wouldn’t delay because there was some confusion on the part of sort of Western public health authorities about it. You’d say, “Look, there’s a strong theoretical case. A lot of countries are doing it. The value if it works is enormous. So get going producing billions of N95 and higher-grade masks right away.” And certainly give everyone cloth masks right away.

Carl Shulman: And then, by the same token, allow challenge trials so that we would have tested all of the vaccines in the first few months of 2020 and have been rolling them out the whole time. So it’s like, you could have a wartime mobilization that would have crushed COVID entirely. And we actually had financial expenditures that were almost wartime level, but almost none of them were applied to the task of actually defeating the virus, only just paying the costs of letting people live with the damage.

Rob Wiblin: Stay home, yeah. Yeah, it’s an interesting phenomenon that seems to have occurred in, I guess the… Yeah, I can’t think of many countries that didn’t seemingly spend more money just on economic stimulus rather than actually preventing the pandemic. And I’m not sure that that’s something I would have predicted ahead of time.

Rob Wiblin: Because I guess obviously yes, there’s like, there’s lobby groups that are very interested in affecting these kinds of stimulus bills so that they get more of the goodies. But at the same time, it seems like all of them have an enormous interest also in preventing the pandemic and spending money on vaccines and masks and all of these things that would stop it because that helps every industry. So I don’t quite understand the political economy behind this somewhat peculiar distribution of effort.

Carl Shulman: Yeah, this was one thing that puzzled me as well. And I actually, I lost a bet with Jeffrey Ladish on this. So some months into the pandemic it seemed pretty clear to me that it was feasible to suppress it. And we’d already seen China go from widespread virus and bring it down to near zero. And a number of other countries, like Australia, New Zealand, Thailand, and so on, had done very well keeping it to negligible levels. And so I thought that the political incentives were such that you would see a drive to use some of these massive spending response bills to push harder.

Carl Shulman: You might’ve thought that the Trump administration, which did go forward with Operation Warp Speed — which was tremendous in terms of mobilization compared to responses to past diseases, but still far short of that full wartime mobilization — you might’ve thought they would conclude, look, the way to win a presidential election is to deliver these vaccines in time and to take the necessary steps, things like challenge trials and whatnot. And so the administration failed to do that, but that seems like it’s not just an issue of dysfunctional political incentives. That seems like serious error, at least as far as I can see, serious error, even in responding to the political incentives.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. Yeah. And it seems like it wasn’t only politicians or like politicians with their motive to get reelected who were holding this back. It was also all kinds of other groups who, as far as I can tell, were kind of thinking about this wrong and had somewhat something of a wrong focus. And so it seems like it was, the intellectual errors were fairly widespread as far as I could tell, at least from my amateur perspective.

Carl Shulman: Yeah. So I think that that’s right, and that problems that are more difficult to understand, that involve less sort of visually obvious connections between cause and effect, they make it harder. And they make it harder at many points in the political process, the policy process, the institutions that have to decide how to respond.

Carl Shulman: Some of them though seem like they were pretty much external political constraints. So Operation Warp Speed, which was paying for the production of vaccine before approval was granted. So that was very valuable. And you know, a bunch of heroic people within the government and outside of it helped to cause that to happen, but in doing that they really had to worry about their careers because, so among other things, mRNA vaccines had not been successfully used at scale before. And so there was fear that you will push on this solution, this particular solution will fail, and then your career —

Rob Wiblin: You’ll be to blame.

Carl Shulman: — will be, yeah, will be very badly hurt and you won’t get a comparable career benefit. If you have a one in 10 chance of averting this disaster and a nine in 10 chance of your particular effort not working, although in fact the vaccines looked good relatively early, then yeah, that may not be in your immediate interest.

Carl Shulman: And so you have these coordination problems even within the government to do bold action, because bold action in dealing with big disasters and when trying things like probabilistic scientific solutions means that a lot of the time you’re going to get some negative feedback. A few times you’re going to get positive feedback. And if you don’t make it possible for those successes to attract and support enough resources to make up for all the failures, then you’ll wind up not acting.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah, there’s asymmetry between if things go wrong, then you get fired and live in disgrace. Versus if you save hundreds of thousands of lives, then people kind of pat you on the back, and maybe it’s a slight advance, but it doesn’t really benefit you all that much. That incentive structure really builds in a sort of extreme cowardice, as far as I can tell, into the design of these bureaucracies. I think, yeah, we kind of see that all the time, that they’re not willing to take risks even when they look really good on expected value terms, or they need an enormous amount of external pressure to push them into doing novel and risky things.

Carl Shulman: Yeah. You see some exceptions to that in some parts of the private sector. So in startups and venture capital, it’s very much a culture of swinging for the fences and where most startups will not succeed at scale, but a few will generate astronomical value, much of which will be captured by the investors and startup holders.

Carl Shulman: But even there, it only goes so far because people don’t value money linearly. So they’re not going to be like equally happy or they’re not going to be delighted to have a chance to trade off $400 million with certainty versus a 50% chance of $1 billion. And as a result, there’s really no institution that is great at handling that sort of rare event.

Carl Shulman: In venture capital it’s helped because investors can diversify across many distinct startups. And so when you make decisions at a high level in a way that propagates nicely down to the lower levels, then that can work. So if you set a broad medical research budget and it’s going to explore hundreds of different options, then that decision can actually be quite likely to succeed in say, staunching the damage of infectious disease.

Carl Shulman: It’s then, transmitting that to the lower levels is difficult because a bureaucrat attached to an individual program, the people recommending individual grants, have their own risk aversion. And you don’t successfully transmit the desire at the top level to we want a portfolio that in aggregate is going to work. It’s hard to transmit that down to get the desired boldness at the very low level. And especially when, if you fail, if you have something that can be demagogued in a congressional hearing. Then yeah, the top-level decision-makers join in the practice of punishing failure more than they reward success among their own subordinates.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. I mean, I guess it could plausibly not be enough motivation even for entrepreneurs in Silicon Valley because they don’t value the money linearly. But it’s like so much more extreme for a bureaucrat at the CDC or the FDA because they may well make zero dollars more and they might just face a lot of frustration getting it up and criticism from their colleagues. At least in Silicon Valley, you also have kind of a prestige around risk-taking and a culture of swinging for the fences that helps to motivate people in addition to just the raw financial return.

Carl Shulman: Yeah, although, of course, that can cut the other way. In that when you have an incentive structure that rewards big successes, and doesn’t hurt you for failures, you want to make sure it doesn’t also not punish you for really doing active large harm. And so this is a concern with some kinds of gain of function research that involve creating more pandemic prone strains of pathogen. Because if something goes wrong, the damage is not just to the workers in the lab, but to the whole world. And so you can’t take this position where you just focus on the positive tail and ignore all the zeros because some of them aren’t zeros. They’re a big negative tail.

How x-risk reduction compares to GiveWell recommendations [00:34:34]

Rob Wiblin: Yeah, yeah, I’ve got a couple of questions about gain-of-function research later on. But maybe let’s come back to the questions I had about these cost-effectiveness estimates. So I guess we saw based on just the standard cost-benefit analysis style that the US government uses to decide what things to spend money on, at least sometimes when they’re using that frame to decide what to spend money on. A lot of these efforts to prevent disasters like pandemics could well be extremely justified, but there’s also a higher threshold you could use, which is if I had a million dollars and I wanted to do as much good as possible, is this the best way to do good? So I suppose for people who are mostly focused on how the world goes for this generation and maybe the next couple of generations, how does work on existential risk reduction in your view compare to, say, giving to GiveWell-recommended charities that can save the life of someone for something like $5,000.

Carl Shulman: Yeah, I think that’s a higher bar. And the main reason is that governments’ willingness to spend tends to be related to their national resources. So the US is willing to spend these enormous amounts to save the life of one American. And in fact, in a country with lower income, there are basic public health gains, things like malaria bed nets or vaccinations that are not fully distributed. So by adopting the cosmopolitan perspective, you then ask not what is the cost relative to the willingness to pay, but rather anywhere in the world where the person who would benefit the most in terms of happiness or other sorts of wellbeing or benefit. And because there are these large gaps in income, there’s a standard that would be a couple of orders of magnitude higher.

Carl Shulman: Now that cuts both ways to some extent. So a problem that affects countries that have a lot of money can be easier to advocate for. So if you’re trying to advocate for increased foreign aid, trying to advocate for preventing another COVID-19, then for the former, you have to convince decision-makers, particularly at the government level, you have to convince countries you should sacrifice more for the benefit of others. In aggregate, foreign aid budgets are far too small. They’re well under 1%, and the amount that’s really directed towards humanitarian benefit and not tied into geopolitical security ambitions and the like is limited. So you may be able to get some additional leverage if you can tap these resources from the market from existing wealthy states, but on the whole, I’m going to expect that you’re going to wind up with many times difference, and looking at GiveWell’s numbers, they suggest… I mean, it’s more like $5,000 to do the equivalent of saving a life, so obviously you can get very different results if you use a value per life saved that’s $5,000 versus a million.

Rob Wiblin: Okay, so for those reasons, it’s an awful lot cheaper potentially to save a life in an extremely poor country, and I suppose also if you just look for… not for the marginal spend to save a life in the US, but an exceptionally unusually cheap opportunity to save a life in what are usually quite poor countries. So you’ve got quite a big multiple between, I guess, something like $4 million and something like $5,000. But then if the comparison is the $5,000 to save a life figure, then would someone be especially excited about that versus the existential risk reduction, or does the existential risk reduction still win out? Or do you end up thinking that both of these are really good opportunities and it’s a bit of a close call?