The value of coordination

This article is now superceded by a more in-depth piece.

This post is intended for people who are already familiar with our key content. If you’re new, read the basics first.

In assessing your positive impact on the world, you need to look at the additional good you do after taking into account what would have happened if you hadn’t acted. But how can you evaluate this?

One way is the “single player approach” – consider what would happen if you act and what would happen if you don’t act, holding everyone else constant, and then look at the difference between the two scenarios.

This approach worked pretty well in the early days of effective altruism, but it starts to break down once you’re part of a community of thousands of people who will change their behaviour depending on what you do.

When you’re part of a community, the counterfactuals become more complex, and doing the most good becomes much more of a coordination problem – it’s a multiplayer rather than a single player game.

In this post, I’ll list five situations where this insight can help us to become even more effective, and I’ll suggest new rules of thumb that I think might be the best guide in a multiplayer world. This is a complex topic, so the answers I give are still tentative. I’m keen to see many more people in the community start thinking about these issues, and preparing the community for its next level of scale.

Summary

| Scenario | Analysis ignoring counterfactuals and coordination | Simple single player counterfactual analysis | Multiplayer counterfactual analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deciding where to donate | Give to whichever charities you think are best until all funds used up. | Try to play donor of last resort. | Contribute your fair share to all charities you think are worth funding or find and fund a charity that passes the bar for community funding. |

| Deciding where to work within the community. | Work wherever you have the best personal fit. | Your impact depends on the difference between your impact in the job compared to the person who’d have that job otherwise. | Work wherever you have the most comparative advantage compared to the community. |

| Determining who should earn to give and who should do direct work | Earn to give if your earning potential is higher than your direct impact potential. | Earn to give if your earning potential is among the highest in the community. | Earn to give if you have a comparative advantage earning compared to direct work in the community. |

| The value of sharing information | Don’t take jobs to gain information. | Don’t take jobs to gain information. | Take jobs to gain information and share it with the community. |

| Attributing impact | Whoever’s the proximate cause of the impact is responsible. | If you do X, but someone else would have done X if you hadn’t, then that’s not part of your impact. | As a first approximation, at the margin, everyone working towards X contributes a fraction of the impact, where the fraction depends on everyone’s skill in doing X. |

Table of Contents

Deciding where to donate

Many large donors in the community aim to give to charities that wouldn’t have received funding otherwise – they want to be the donor of last resort. This is a good aim, but if lots of people do it, you end up with no-one willing to donate because they each believe that others will donate if they don’t.

In practice, what happens is that fundraising takes longer than it should because many donors wait and see if someone else will donate before deciding. This is costly because fundraising is very distracting – it often ends up the top idea in your mind.

Everyone trying to play donor of last resort could also create perverse incentives. For instance, it encourages organisations to cut their reserves (or hide them off balance sheet) because having lower reserves makes it seem like they have greater financial need, even though it would be better if every organisation had 12 months’ reserves. It also incentivises them to increase their fundraising targets to maximize the apparent funding gap: if you ask for $100 you may well get the $30 you actually need, but if you ask for $30 you’ll more likely to get only $20.

Being the donor of last resort is also not as valuable as it first looks once you’re part of a community. If you give to an organisation and use up its room for more funding, then you free up another donor to go donate somewhere else. If that person shares your values and has reasonable judgement, then they’ll donate somewhere else that’s pretty good. This is especially true if you are modest about your own judgement. If someone else in your community who is smart thinks something is a good donation opportunity, then you should assign a reasonable probability to them being right.

To give a real example, once all the funding gaps for meta-charities are used up, marginal donors will probably give to GiveWell recommended charities instead. If your next best alternative to giving to a meta-charity is donating to a GiveWell recommended charity, then there’s little reason to try to play donor of last resort. If you think GiveWell recommended charities are a bit worse than where you would donate otherwise, then you should have a modest preference for playing donor of last resort, but you still need to weigh this against the extra costs you pose for organisations (as discussed above).

What should we aim to achieve instead of trying to be a donor of last resort? Here are a couple of options to improve the efficiency of fundraising in the community:

Give your fair share

If a group of donors agree that an organisation should have its funding gap filled, then they should get together and all contribute their fair share. One option for fair shares is for each donor to contribute in proportion to the total amount of money they’re giving this year. (Thanks go to Nick Beckstead for this proposal.)

For instance:

- Two donors agree an organisation should receive $100.

- Donor A is giving $200 this year in total.

- Donor B is giving $100 this year in total.

- So Donor A gives $66 to the organisation, and Donor B gives $33.

There are many additional complications. For instance if Donor A thinks the organisation is better than B, should A contribute even more? Perhaps. Nevertheless, I still think the fair share approach is better than Donor A and B playing chicken and trying to force the other to fill the gap.

The bar approach

The weakness of the fair share approach is that it assumes you know about all the charities that are worth funding, and so do all the other donors. You also have to communicate with the other donors to divide up the shares. Figuring out which charities are worth funding and communicating with other donors is a cost for both the donor and the charity – the donor has to do research and the charity has to provide information.

Another approach would be to try to determine which funding opportunities are good enough for the community to fund as a whole (i.e. they pass the bar for funding), and then once you’ve found one, donate all your money to that charity until the gap is used up, you run out of funds or you reach 33% of the charity’s budget. The last condition is because if you cover too much of a charity’s budget it can stop them from building a diversified funding base, putting them at greater risk in the long-term. (Thank you to Alex Gordon-Brown for emphasising this in the comments).

This process can be faster for you and the charities you’d talk to, but it also saves the time and attention of later donors, who don’t have to consider it in the option set of marginal options (because it will certainly be funded — this was always true, but now it is transparent). If everyone does this, then the community reduces research costs dramatically, but all the charities that are above the bar get funded.

In reality, you might want to do a combination of both the bar approach and the fair share approach, depending on how much information you have. Either way, the focus is much more on donating once you’ve found a reasonable opportunity, rather than trying to hold out for opportunities no-one else would take. And both approaches lead to substantially reduced costs compared to people playing donor of last resort. (Thanks go to Owen Cotton-Barratt for this proposal.)

Deciding where to work in the community

When we try to hire people, they often want to know how good they’d be at the role compared to the person we’d otherwise hire, because they’re concerned they’d be replaceable at 80,000 Hours.

This usually doesn’t seem very relevant to me, because we normally have a strong preference for the best person compared to the second best. Small differences in ability also translate into big differences in outcomes.

Putting all that to one side, however, it’s also not a good question because it doesn’t show a good analysis of the counterfactuals.

Suppose we’re choosing between Amy and Bob. Amy is a little better at the role, but not much. So Bob reasons that either one of them will be highly replaceable. However, if Amy takes the job, Bob will go and take some other high impact job within the community, creating significant extra impact that won’t happen if Amy doesn’t take the job. And if she doesn’t take the job and Bob does, that will cause another chain of replacements, so overall analysing the counterfactuals gets very messy.

Here’s a real example: When we were hiring a researcher in the summer, several said they were concerned they’d be replaceable and didn’t join. In the end, Rob Wiblin joined the team, who’s probably better than the people we would have hired otherwise. So on the single player perspective the other candidates were more than replaceable, they were actually worse than their replacement would have been. However, Rob had to leave his job as the Executive Director at the Centre for Effective Altruism. That resulted in Seb shifting 50% of his time to that role, reducing his time for the Global Priorities Project. And that forced GPP to spend time looking for another Executive Director. So if someone else had taken the job instead of Rob, GPP wouldn’t need to hire an Executive Director, and we wouldn’t have had to undertake two disruptive transitions.

What should be done instead? Rather than thinking about how good you’ll be at the role compared to the person who would take the job instead of you, focus on taking the role where you have the biggest comparative advantage within the community. A good first approximation is taking the job where you have the best personal fit (though it can differ, as I’ll explain later). And, also think about the merits of each organisation as well as career capital, exploration and all the usual factors we talk about.

This example is a specific case of a bad analysis of replaceability, of which we’ve seen quite a few.

Determining who should earn to give and who should do direct work

Earning to give is already a type of coordination – rather than everyone pursuing direct work (e.g. taking jobs in non-profits), a fraction of people can instead pursue high earning jobs and fund others to do direct work. This leads to a higher overall number of people doing direct work.

But which fraction of people should earn to give compared to doing direct work? A naive answer is that the people with the highest earning potential should earn to give and the others should do direct work.

However, I think a better answer is that only the people with the highest comparative advantage in the community to get high paying jobs should earn to give and the others should do direct work.

This means that, if the highest earning person in the community could also be even better than everyone else at direct work, they should do direct work despite their higher earning potential. (I think you can also get scenarios when you shouldn’t even do what you’re overall best at, like Ricardo’s original cloth and wine example.)

To figure out your comparative advantage: compare your earning power to other community members, then compare your direct work potential, then pursue whichever of them you are relatively best at (rather than doing what you’re best at compared to people in general).

You can assess this by asking organisations in the community how much they would want to receive in extra donations in order to be indifferent between not hiring you and getting the money. Then compare this to how much you’d be able to donate by earning to give.

Going to the next level of depth, I think you should take into account both which job you’d be best at compared to people in general (personal fit) and your comparative advantage compared to other community members. This is because personal fit is still important for boosting your career capital and job satisfaction. In addition, coordination in the community isn’t perfect, so we should care about both personal fit and comparative advantage. The better coordination is in the community, the more you should focus on comparative advantage, and the worse it is, focus on what you’re best at compared to people in general.

Who might this reasoning affect within the effective altruism community? There are lots of people working in software engineering and similar areas pursuing earning to give. Many of them reason: “I’m pretty good at software engineering so I should earn to give and pay others to do direct work.” If the community were more balanced then this would be true, but when a substantial fraction of the community could be good at software engineering, it breaks down. Some people who have good personal fit with software engineering probably have a comparative advantage in direct work in the community, even if they’d be worse at direct work than software engineering compared to people in general. Ben Kuhn has written more about examples like these.

There’s more theoretical detail in these great draft notes by Paul Christiano.

The value of sharing information

From a single player perspective, you only get one career, so you should work out which options are best and take them.

However from a multiplayer perspective, there’s another option. You can try out one path, then share what you learn with other community members (both now and in the future) helping them to improve their choices. By doing this, the community can have an overall greater impact than if everyone just does what they guess is best right now.

I sketch out some areas that seem worth exploring in the talent gaps post.

One response to this is that a single person going into a career doesn’t result in much learning for the community. This has not been my experience – I’ve learned a lot from talking to reflective members of our community who have been in a career path for a couple of years. Much of our career reviews are based on these conversations.

Attributing impact

Suppose Amy persuades Peter to take the Giving What We Can pledge to give 10% of their income.

Now suppose that if she hadn’t persuaded him, Bob would have persuaded him instead.

How much impact has Amy had?

The single player answer is zero, because Peter would have taken the pledge anyway. But again, this is bad analysis of the counterfactuals.

First, in reality, there will always be some chance that if Amy hadn’t persuaded Peter, Bob would also have failed to have persuade him, and Peter would have never taken the pledge. Amy has probably made it more likely that Peter would take the pledge, and so she has had some impact, it’s just less than 100% of the value of the pledge.

Moreover, let’s think about what would have happened if Amy had never persuaded Peter to take the pledge. Maybe it’s true that Bob would have persuaded him instead, but that takes up Bob’s time which could have been spent persuading someone else. And there are many other complex possibilities to consider.

A common misconception is that the credit for an action can’t add up to more than 100%. But it’s perfectly possible for both people to be responsible. Suppose Amy and Bob see someone drowning. Amy performs CPR while Bob calls the ambulance. If Amy wasn’t there to perform CPR, the person would have died while Bob called the ambulance. If Bob wasn’t there, the ambulance wouldn’t have arrived in time. Both Amy and Bob saved a life, and it wouldn’t have happened if either was there. So, both are 100% responsible.

You can also have cases where both would have done it otherwise, so each person gets zero credit!

When you get lost in the thicket of counterfactuals, it’s easy to lose sight of the big picture: more people persuading others to take the pledge means more people will take the pledge.

How should we attribute impact instead? If a group of people are persuading lots of people to take the pledge, then each person is likely responsible for some fraction of the impact. Within the group, it probably makes sense to allocate credit roughly in proportion to how good each person is at persuading others to take the pledge. This gets you back to the answer you’d get if you ignored counterfactuals in the first place.

For instance, suppose:

- Carla persuades 10 people to take the pledge each year.

- David persuades 5 people.

- For each person, if Carla didn’t persuade them, there’s a good chance David would have persuaded them instead, and vice versa.

How should we allocate impact?

- Ignoring counterfactuals, we’d say Carla caused 10 and David caused 5.

- Since any of those people could have been persuaded by the other individual, the naive single player view might say that no-one caused anyone to take the pledge!

- Or perhaps the single player would say Carla caused 10 – N people to take the pledge, where N is the number David would have persuaded otherwise, and similarly for David. Overall, we end up with Carla and David both having much less impact than it initially seemed, and a significant proportion of “uncaused” pledges.

- Or perhaps, there’s a fraction of pledges that wouldn’t have happened without both Carla and David taking action, and Carla and David have more impact than it looks ignoring counterfactuals.

- My proposal is that once we think through all these counterfactual scenarios and average over them, a decent approximation is simply that Carla caused ⅔ of the pledges, i.e. 10, and David caused ⅓, i.e. 5 (at the margin – if there’s diminishing returns, then factor them in separately).

For more on this, see Brian Tomasik’s post on the 100 yard line model.

Conclusion

We care about our impact compared to what would have happened otherwise, but analysing the counterfactuals gets really complicated. It gets even more complicated once you’re part of a community that adapts its behavior in response to you. We need to develop new rules of thumb for guiding behaviour that work better than the rules of thumb you get from the single player perspective. In this post, I’ve suggested a couple: think more about your comparative advantage within the community rather than what you’re best at in general; look out for ways you can coordinate with the rest of the community, and contribute your fair share rather than trying to play donor of last resort.

Thanks especially to Toby Ord for discussing these ideas with me, and to everyone who commented on the document.

Appendix – Cause selection – do we have a stag problem?

Here’s some more speculative thoughts in the same theme as the above.

The single player perspective approach to systemic change

One objection that’s often made to the single player perspective is that it ignores systemic change. I think this is true in one sense but not true in another.

The single player perspective still has room for systemic change. Here’s how you would model it:

- Calculate V, the value of the systemic change.

- Calculate p, the increase in the probability of the systemic change happening if you work towards it.

- Then the expected value of the systemic change is V*p.

- Then working on systemic change is the highest value option whenever V*p is greater than your next best option.

However, if other people will change their actions in response to yours, then you end up in game theory, and it gets more complicated. One way of looking at this is that it’s very hard to estimate the probability p directly.

The stag problem

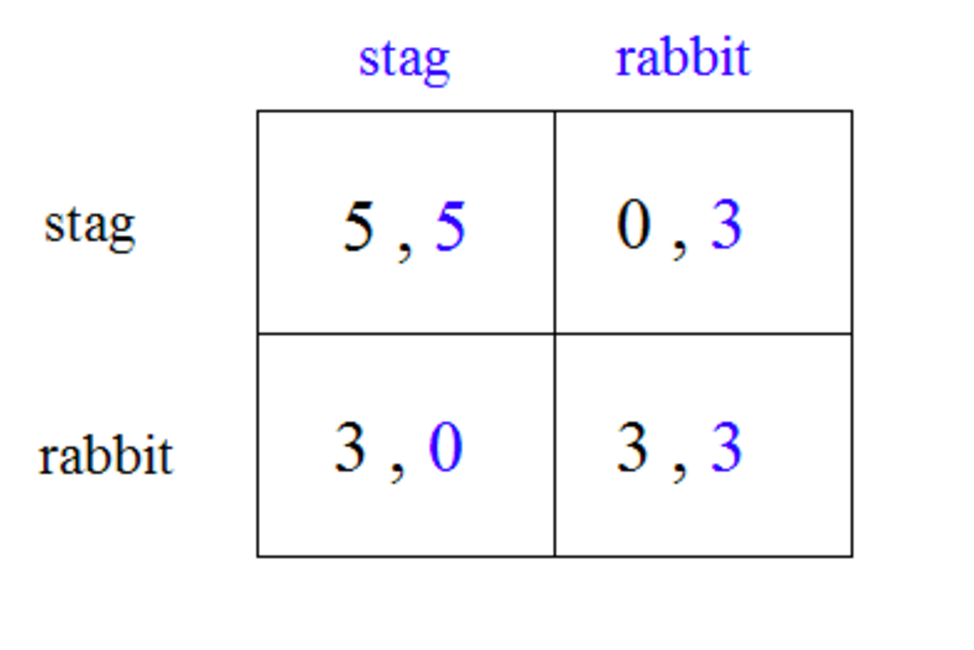

One possibility is that you’re in a “stag hunt” coordination problem.

Suppose there are two outcomes – catching a stag or catching a rabbit. If two people work together, they can catch the stag; if each works individually they’ll only capture rabbits.

Clearly, it’s better to coordinate and catch the stag.

If we think too much about the single player perspective, then we might all end up catching rabbits and not the stag. You could see this as one of the criticisms Ami Srinivasan made of effective altruism in the London Review of Books. By only focusing on small changes the community can make to the world at the margin, we could ignore the possibility of much bigger changes that would be possible if we got lots of people involved.

In practice, I’m not sure this is a pressing issue for the community. Stag hunt situations arise rarely in real life, because if both groups can communicate, then they’ll both go for the stag. Unlike prisoner’s dilemma type situations, it’s in both people’s interest to coordinate.

It seems like Stag situations will only arise in practice when each party isn’t even aware the stag exists. I think there’s some danger of this applying to the effective altruism community. The solution, however, is more research into cause selection with a focus on large scale changes, and on that front, the community is pushing ahead.

Prisoner’s dilemma

If, however, we are in a big prisoner’s dilemma type situation, then it’s harder to fix. Imagine everyone has two options: work with the system or reject the system. From an individual perspective, it could be better to work with the system. However, if lots of people rejected the system simultaneously, then the outcome could be even better than if everyone worked with the system. A single player perspective will probably not pick this up.

Personally, I think there probably are cases when we’re in a society-wide prisoner’s dilemma, but it’s unclear how bad these are and whether there’s much we can do about it. I’d welcome more research.

Read more: our in-depth article on coordination first released in 2018.