#191 – Carl Shulman on government and society after AGI (Part 2)

This is the second part of our marathon interview with Carl Shulman. The first episode is on the economy and national security after AGI. You can listen to them in either order!

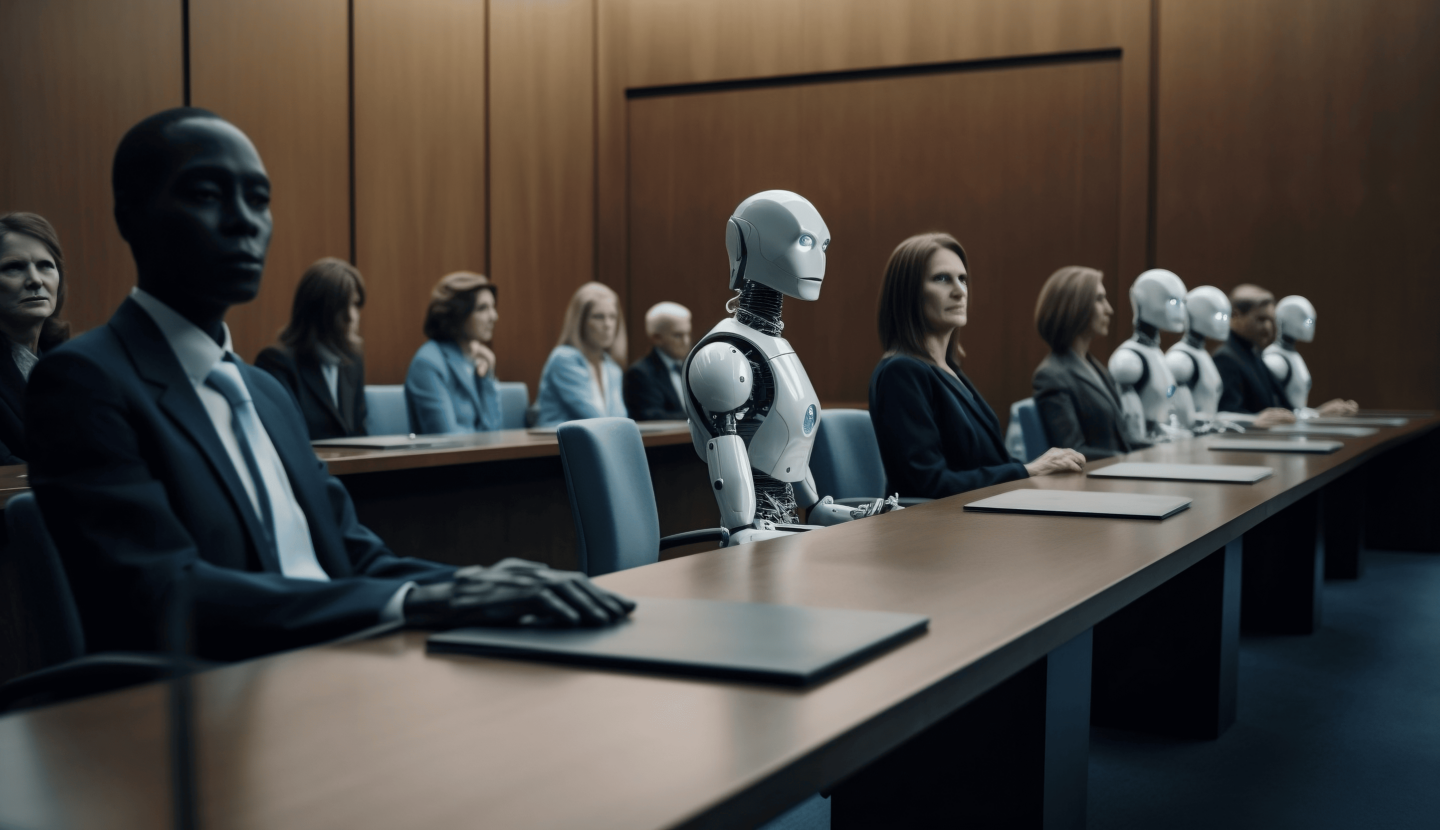

If we develop artificial general intelligence that’s reasonably aligned with human goals, it could put a fast and near-free superhuman advisor in everyone’s pocket. How would that affect culture, government, and our ability to act sensibly and coordinate together?

It’s common to worry that AI advances will lead to a proliferation of misinformation and further disconnect us from reality. But in today’s conversation, AI expert Carl Shulman argues that this underrates the powerful positive applications the technology could have in the public sphere.

As Carl explains, today the most important questions we face as a society remain in the “realm of subjective judgement” — without any “robust, well-founded scientific consensus on how to answer them.” But if AI ‘evals’ and interpretability advance to the point that it’s possible to demonstrate which AI models have truly superhuman judgement and give consistently trustworthy advice, society could converge on firm or ‘best-guess’ answers to far more cases.

If the answers are publicly visible and confirmable by all, the pressure on officials to act on that advice could be great.

That’s because when it’s hard to assess if a line has been crossed or not, we usually give people much more discretion. For instance, a journalist inventing an interview that never happened will get fired because it’s an unambiguous violation of honesty norms — but so long as there’s no universally agreed-upon standard for selective reporting, that same journalist will have substantial discretion to report information that favours their preferred view more often than that which contradicts it.

Similarly, today we have no generally agreed-upon way to tell when a decision-maker has behaved irresponsibly. But if experience clearly shows that following AI advice is the wise move, not seeking or ignoring such advice could become more like crossing a red line — less like making an understandable mistake and more like fabricating your balance sheet.

To illustrate the possible impact, Carl imagines how the COVID pandemic could have played out in the presence of AI advisors that everyone agrees are exceedingly insightful and reliable.

To start, advance investment in preventing, detecting, and containing pandemics would likely have been at a much higher and more sensible level, because it would have been straightforward to confirm which efforts passed a cost-benefit test for government spending. Politicians refusing to fund such efforts when the wisdom of doing so is an agreed and established fact would seem like malpractice.

Low-level Chinese officials in Wuhan would have been seeking advice from AI advisors instructed to recommend actions that are in the interests of the Chinese government as a whole. As soon as unexplained illnesses started appearing, that advice would be to escalate and quarantine to prevent a possible new pandemic escaping control, rather than stick their heads in the sand as happened in reality. Having been told by AI advisors of the need to warn national leaders, ignoring the problem would be a career-ending move.

From there, these AI advisors could have recommended stopping travel out of Wuhan in November or December 2019, perhaps fully containing the virus, as was achieved with SARS-1 in 2003. Had the virus nevertheless gone global, President Trump would have been getting excellent advice on what would most likely ensure his reelection. Among other things, that would have meant funding Operation Warp Speed far more than it in fact was, as well as accelerating the vaccine approval process, and building extra manufacturing capacity earlier. Vaccines might have reached everyone far faster.

These are just a handful of simple changes from the real course of events we can imagine — in practice, a significantly superhuman AI might suggest novel approaches better than any we can suggest here.

In the past we’ve usually found it easier to predict how hard technologies like planes or factories will change than to imagine the social shifts that those technologies will create — and the same is likely happening for AI.

Carl Shulman and host Rob Wiblin discuss the above, as well as:

- The risk of society using AI to lock in its values.

- The difficulty of preventing coups once AI is key to the military and police.

- What international treaties we need to make this go well.

- How to make AI superhuman at forecasting the future.

- Whether AI will be able to help us with intractable philosophical questions.

- Whether we need dedicated projects to make wise AI advisors, or if it will happen automatically as models scale.

- Why Carl doesn’t support AI companies voluntarily pausing AI research, but sees a stronger case for binding international controls once we’re closer to ‘crunch time.’

- Opportunities for listeners to contribute to making the future go well.

Producer and editor: Keiran Harris

Audio engineering team: Ben Cordell, Simon Monsour, Milo McGuire, and Dominic Armstrong

Transcriptions: Katy Moore