#74 – Dr Greg Lewis on COVID-19 and reducing global catastrophic biological risks

#74 – Dr Greg Lewis on COVID-19 and reducing global catastrophic biological risks

By Howie Lempel, Robert Wiblin and Keiran Harris · Published April 17th, 2020

On this page:

- Introduction

- 1 Highlights

- 2 Articles, books, and other media discussed in the show

- 3 Transcript

- 3.1 Rob's intro [00:00:00]

- 3.2 The interview begins [00:03:15]

- 3.3 What is COVID-19? [00:16:05]

- 3.4 If you end up infected, how severe is it likely to be? [00:19:21]

- 3.5 How does COVID-19 compare to other diseases? [00:25:42]

- 3.6 Common confusions around COVID-19 [00:32:02]

- 3.7 What types of interventions were available to policymakers? [00:46:20]

- 3.8 Nonpharmaceutical Interventions [01:04:18]

- 3.9 What can you do personally? [01:18:25]

- 3.10 Reflections on the first few months of the pandemic [01:23:46]

- 3.11 Global catastrophic biological risks (GCBRs) [01:26:17]

- 3.12 Counterarguments to working on GCBRs [01:45:56]

- 3.13 How do GCBRs compare to other problems? [01:49:05]

- 3.14 Careers [01:59:50]

- 3.15 The response of the effective altruism community to COVID-19 [02:11:42]

- 3.16 The response of 80,000 Hours to COVID-19 [02:28:12]

- 3.17 Rob's outro [02:36:22]

- 4 Learn more

- 5 Related episodes

A painting illustrating the Black Death — the worse pandemic in human history, which killed 30-60% of Europe's population.

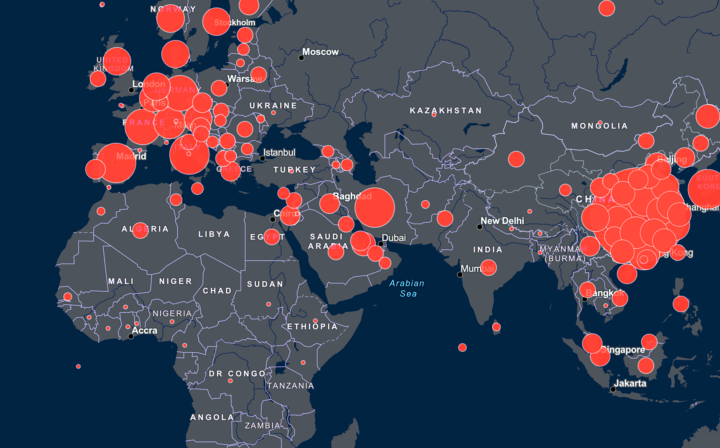

Our lives currently revolve around the global emergency of COVID-19; you’re probably reading this while confined to your house, as the death toll from the worst pandemic since 1918 continues to rise.

The question of how to tackle COVID-19 has been foremost in the minds of many, including here at 80,000 Hours.

Today’s guest, Dr Gregory Lewis, acting head of the Biosecurity Research Group at Oxford University’s Future of Humanity Institute, puts the crisis in context, explaining how COVID-19 compares to other diseases, pandemics of the past, and possible worse crises in the future.

COVID-19 is a vivid reminder that we are vulnerable to biological threats and underprepared to deal with them. We have been unable to suppress the spread of COVID-19 around the world and, tragically, global deaths will at least be in the hundreds of thousands.

How would we cope with a virus that was even more contagious and even more deadly? Greg’s work focuses on these risks — of outbreaks that threaten our entire future through an unrecoverable collapse of civilisation, or even the extinction of humanity.

If such a catastrophe were to occur, Greg believes it’s more likely to be caused by accidental or deliberate misuse of biotechnology than by a pathogen developed by nature.

There are a few direct causes for concern: humans now have the ability to produce some of the most dangerous diseases in history in the lab; technological progress may enable the creation of pathogens which are nastier than anything we see in nature; and most biotechnology has yet to even be conceived, so we can’t assume all the dangers will be familiar.

This is grim stuff, but it needn’t be paralysing. In the years following COVID-19, humanity may be inspired to better prepare for the existential risks of the next century: improving our science, updating our policy options, and enhancing our social cohesion.

COVID-19 is a tragedy of stunning proportions, and its immediate threat is undoubtedly worthy of significant resources.

But we will get through it; if a future biological catastrophe poses an existential risk, we may not get a second chance. It is therefore vital to learn every lesson we can from this pandemic, and provide our descendants with the security we wish for ourselves.

Today’s episode is the hosting debut of our Strategy Advisor, Howie Lempel.

80,000 Hours has focused on COVID-19 for the last few weeks and published over ten pieces about it, and a substantial benefit of this interview was to help inform our own views. As such, at times this episode may feel like eavesdropping on a private conversation, and it is likely to be of most interest to people primarily focused on making the long-term future go as well as possible.

In this episode, Howie and Greg cover:

- Reflections on the first few months of the pandemic

- Common confusions around COVID-19

- How COVID-19 compares to other diseases

- What types of interventions have been available to policymakers

- Arguments for and against working on global catastrophic biological risks (GCBRs)

- Why state actors would even use or develop biological weapons

- How to know if you’re a good fit to work on GCBRs

- The response of the effective altruism community, as well as 80,000 Hours in particular, to COVID-19

- And much more.

Get this episode by subscribing to our podcast on the world’s most pressing problems and how to solve them: type “80,000 Hours” into your podcasting app. Or read the transcript below.

Producer: Keiran Harris.

Audio mastering: Ben Cordell.

Transcriptions: Zakee Ulhaq.

Highlights

The thinking behind social distancing

A lot of the physical distancing recommendation you’re seeing from various governments, including my own in the UK, is essentially trying to act as an insurance against this risk of people spreading it to others without either person realizing they’re at risk. So, in a sense, this idea of like, avoid all non-essential contact with others, doesn’t have a rider of like, “Oh, if both of you feel well it’s fine,” partly for reasons like this. But also people may not always recollect what symptoms they have. If you’re coughing like once or twice a day or something, maybe that’s a sign of a very mild infection for argument’s sake. But you may not notice that, potentially, and think you’re well. And so given all these things, there’s this general urge towards just basically making as little in-person social contact as possible as a way of reducing the spread of the disease.

If you knew for sure that only people who were having symptoms could spread it, which may have been the case in SARS, although there’s slightly more of a story there, then maybe this wouldn’t be as necessary over and above a milder principle of, “Please isolate when you’re feeling unwell”. But unfortunately that doesn’t seem to be the case, and hence why we’re seeing what we’re seeing now.

Why will it take at least 12-18 months to get a vaccine?

It’s worth stressing that 12 to 18 months would be fairly fast. It’s almost unprecedentedly fast by typical vaccine timelines. So the question is why does it usually take so long, perhaps? And maybe one way of looking at it is to go through the stages one might do to develop a vaccine and manufacture it. And maybe that would give some insight as to why this might take awhile.

So the initial step is sort of doing basic science or preclinical work in animals or cell culture. Basically to see if your vaccine does what it’s supposed to do, which is essentially provoke the right immune response. And then once you’ve got something which seems to work in your animal or whatever, you then want to see if it actually is safe to give to a person. And so this is usually what’s called phase one study, which is a phase of study where you give small groups of people vaccinations to test safety. And particularly with coronavirus vaccination, that is a major worry insofar as what we saw in previous attempts to vaccinate against something like SARS was these vaccines could backfire, in that they can actually enhance disease rather than protect against it through a variety of mechanisms, which obviously is very bad. You don’t want to mass administer something that then actually makes people have worse outcomes rather than protecting from it. So that isn’t straightforward to navigate.

And then once you do that, you can then run what’s called phase two and phase three trials, where you basically try to test efficacy. Does it actually protect you from the infection? Trials can take quite a while, because you have to maybe follow up for quite a long time to see how much protective effect you’re really getting. I think there was a recent proposal by Lipsitch, Eyal, Smith: which is you might be able to say sometime if instead of doing the typical way we do it, which I described just now, you do what’s called a challenge study, which is sort of what you do, as it were, safety and efficacy studies at once on a population.

So, this essentially means you give someone a vaccine, and then you give them the agent which causes the infection on a sort of RCT basis and see if it actually does work. Obviously, the ethics issues around that are very fraught, which they cover in their paper, which might be worth having a link. But maybe something worth contemplating in terms of maybe saving you some time. And we do see vaccine challenge studies done in some contexts. I know there’s one for malaria. There’s been other ones as well.

What can you do personally?

So typical recommendations to give everyone would very much be good citizenship norms of what typical governments are also recommending people do. And so these are maybe not in good order at the moment but it’s like, “Wash your hands regularly before having food, before going out, before coming back. Generally, if in doubt, wash your hands”. There’s a 20 second recommendation. There’s also a six stage hand washing technique you can look up if you really like. There’s also the respiratory hygiene issue of “Please don’t cough into your hands but cough into a tissue or, if worst comes to worst, inside your elbow or something”.

When it used to be relevant there was obviously “Please isolate yourself if you think you might be unwell, and don’t come into work when you’re sick”. Obviously now in many countries, including my own, the key recommendation is essentially this, which is to avoid all nonessential travel and avoid all nonessential contact with others. And the more people who do this, I’ll expect the better things will be. So I struggle to emphasize it enough in terms of doing all of those things. Now, in terms of particular ways to help, I know 80K published,… Well a couple of days from me saying this, a post on if you’re mired to help, what you can do. I don’t have many obvious additions to this list. In terms of the question of whether rather than what, I would maybe strike some note of caution for a few reasons.

One is that this is probably now maybe the least neglected topic on the planet at the moment, and so the window for having a really outsized impact, like being early, is closed. And this reason may be the case that folks that have prior knowledge or expertise in certain areas, there may not be very good things that they can do to contribute versus what they will be doing otherwise. Because there are still many other problems in the world unfortunately besides COVID-19, and those problems haven’t gone away. And so whether to switch from one to the other is uncertain. It’s also something I’m somewhat grappling with myself as I discussed earlier. So maybe, but maybe not and maybe less so if you don’t have a relevant background which would make you well positioned to contribute would be my best guess.

Global catastrophic biological risks

By any commonsense definition of the term COVID-19 is a global catastrophe, but what we tend to have in mind when we talk about these things are events of such large magnitude that they place the long-term trajectory of humankind in peril. There are a few different definitions of what GCRs are. That’s one. Open Phil’s one talks about how it could globally destabilize enough to permanently worsen humanity’s future or lead to human extinction and you get things along these lines. So it’d have to be like extremely, extremely bad events. And so I don’t think any pandemic in human history has ever really got to that sort of level.

So things like the Black Death, or 1918 influenza or things like the Justinian plague I also don’t think other major current health crises at the moment would also count as these sorts of risks. So, for example, I don’t think antimicrobial resistance is a GCBR, nor HIV/AIDS and so on and so on and so forth. None of which is meant to say these things are trivial or they aren’t important or anything along those lines. But it’s to sort of give a sense of what I have in mind, is events of a greatly different order to these undoubtedly extremely severe threats to global health. And so given COVID-19 falls in this set of very severe threats, it nonetheless doesn’t rise to the level of a threat to human civilization, which I guess you can consider reassuring, although it’s obviously not much for reassurance.

Accidental vs. deliberate misuse of biotechnology

We haven’t really seen many events which have been human caused which are similarly bad to naturally arising events like the typical death toll from scientific accidents or by terrorist attacks or anything else. It’s comfortably less than most other infectious diseases at any given year. So you’re often trying to weigh up within this, which seems risky given the lack of a track record.

And there’s also, I guess, another annoying philosopher’s point whereby the distinction between accidental and deliberate isn’t perfectly crisp. So you can imagine a Dr. Strangelove scenario where someone deliberately makes something very nasty but then another agent uses it without authorization: so it’s the unauthorized use of something that’s deliberately made, but that’s somewhat an accident by light of the person who made it in the first place. Or there could be a thing whereby someone makes something very nasty and accidentally deploys that without intending to. Which again there’s this mix between… Well, you’re deliberately making something very bad, but you weren’t deliberately like releasing it to cause harm. So that’s like a small point. But in terms of the general sketch. One expectation, well hopefully one expectation is, there are more people who are well-intentioned than badly intentioned, so maybe there’s a higher rate of people who have good intentions who then make mistakes versus people with bad intentions doing these deliberately.

That being said, if you’re trying to cause a very, very bad thing to happen, you’re probably more likely to achieve it. Trying to do it deliberately rather than doing so by accident. But all of this is deeply uncertain. The evidence I’ll offer in favor is conjecture: is if you look at other things in terms of single event casualty counts. Maybe one comparison would be, for example, motor vehicle accidents. So most of those happen by accident, and there are far more accidental deaths from cars, roughly speaking, than people deliberately using cars kill each other. But if you look at something like the largest casualty events involving a car or indeed a plane or other things, you see that most of these are from deliberate acts of misuse. So unfortunately, vehicle ramming attacks, for example, tend to have a much higher average death toll than the typical car accident, even though there’s many more car accidents.

Articles, books, and other media discussed in the show

80,000 Hours Annual Review – December 2019

80,000 Hours work on COVID-19

- Landing page with all our COVID-related research and links to the top resources we’ve found

Good news about COVID-19 (our most viral article in a few years)

COVID-19 essential facts and figures

How to best overcome COVID-19 through work and volunteering

Top donation options

List of 200 specific job vacancies, volunteering opportunities & funding sources

The 12 best policy steps to stop pandemics including this one (podcast)

Introduction to Greg’s problem profile on reducing catastrophic biological risks more generally

Greg’s work

- Reducing global catastrophic biological risks

- Greg’s personal site

- In defence of epistemic modesty

- Reality is often underpowered

- Information Hazards in Biotechnology by Gregory Lewis, Piers Millett, Anders Sandberg, Andrew Snyder-Beattie, & Gigi Gronvall (2019)

Everything else

- How does the offense-defense balance scale? by Ben Garfinkel & Allan Dafoe (2019)

- How can doctors do the most good? An interview with Dr Gregory Lewis by Pablo Stafforini (2015)

- Living High and Letting Die: Our Illusion of Innocence by Peter Unger (1996)

- Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID19 mortality and healthcare demand by Neil M. Ferguson et al. (2020)

- The Black Death on Wikipedia

- The Plague of Justinian on Wikipedia

- The Spanish Flu on Wikipedia

- The Columbian Exchange on Wikipedia

- The Justianic Plague: An Inconsequential Pandemic? by Lee Mordechai, Merle Eisenberg, Timothy P. Newfield, Adam Izdebski, Janet E. Kay, & Hendrik Poinar (2019)

- Event 201: A Global Pandemic Exercise — The Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security

- The next outbreak? We’re not ready — TED Talk by Bill Gates

- Human challenge studies to accelerate coronavirus vaccine licensure by Nir Eyal, Marc Lipsitch, & Peter G Smith (2020)

- Manufacturing medical countermeasures against catastrophic biothreats

— Daniel Gastfriend (EAG: SF 2019) - Policy Brief: Evidence-Informed Social Distancing Policies for African Countries by IDInsight (2020)

- Nextstrain

- Drew Endy Lab

- Barriers to Bioweapons: The Challenges of Expertise and Organization for Weapons Development by Sonia Ben Ouagrham-Gormley (2014)

- Ways people trying to do good accidentally make things worse, and how to avoid them by Robert Wiblin and Howie Lempel (2018)

- Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE): Coronavirus (COVID-19) response

- Maximal Cluelessness by Andreas Mogensen (2019)

- The Moral Value of Information by Amanda Askell

- Doing Good Better: How Effective Altruism Can Help You Make A Difference by William MacAskill (2015)

- The Precipice: Existential Risk and the Future of Humanity by Toby Ord (2020)

- IMDB: Dr Strangelove (1964)

Transcript

Table of Contents

- 1 Rob’s intro [00:00:00]

- 2 The interview begins [00:03:15]

- 3 What is COVID-19? [00:16:05]

- 4 If you end up infected, how severe is it likely to be? [00:19:21]

- 5 How does COVID-19 compare to other diseases? [00:25:42]

- 6 Common confusions around COVID-19 [00:32:02]

- 7 What types of interventions were available to policymakers? [00:46:20]

- 8 Nonpharmaceutical Interventions [01:04:18]

- 9 What can you do personally? [01:18:25]

- 10 Reflections on the first few months of the pandemic [01:23:46]

- 11 Global catastrophic biological risks (GCBRs) [01:26:17]

- 12 Counterarguments to working on GCBRs [01:45:56]

- 13 How do GCBRs compare to other problems? [01:49:05]

- 14 Careers [01:59:50]

- 15 The response of the effective altruism community to COVID-19 [02:11:42]

- 16 The response of 80,000 Hours to COVID-19 [02:28:12]

- 17 Rob’s outro [02:36:22]

Rob’s intro [00:00:00]

Robert Wiblin: Hi listeners, this is the 80,000 Hours Podcast, where each week we have an unusually in-depth conversation about one of the world’s most pressing problems and how you can use your career to solve it. I’m Rob Wiblin, Director of Research at 80,000 Hours.

Today, we’re taking a step back towards non-COVID-19 content — with an episode that spends just two-thirds of its time dealing with COVID-19.

Like many others, we’ve been focused almost exclusively on the global pandemic for the last few weeks, but the last third of today’s interview is a reminder that some of the other most pressing problems in the world haven’t gone away.

Dr Greg Lewis worked as a doctor before moving to Oxford’s Future of Humanity Institute to research potential catastrophic risks from advancing biotechnology — basically, biological threats that really would make COVID-19 look like the common cold.

Greg wrote our lovely new problem profile on ‘Reducing global catastrophic biological risks’. We’ll link to that in the show notes and Keiran made an audio version which should be the previous entry in this podcast feed.

And today Greg’s speaking with my colleague Howie Lempel, who’ll be familiar to regular listeners.

He was a guest far back in episode #4 Howie Lempel on why we aren’t worried enough about the next pandemic—and specifically what we can do to stop it, and then joined the 80,000 Hours team in 2018.

He was also my co-host back on episode number 73 – ‘Phil Trammell on patient philanthropy and waiting to do good’, which aired all the way back on March 17th, 2020 – which now seems like an aeon ago.

We’ve also done two COVID-19 themed episodes together, the latest is called ‘Rob & Howie on the menace of COVID-19, and what both governments & individuals might do to help’ and came out on March 19.

But today is Howie’s first episode hosting by himself. The team thought he did a great job, and we’re excited for him to host more episodes in the future.

If you do want to read more about COVID-19, the 80,000 Hours team has worked overtime lately to produce a fantastic package of 10 pieces about how to stop the pandemic.

That includes an article on how to use your talents to solve the crisis, one on where to direct donations, a database of 250 job opportunities and 60 funding sources, a guide to the essential facts about the disease, and if you need a pick-me-up to keep going, a piece on some of the good news we’ve seen in March.

It’s really fairly comprehensive.

Please take a look and share any you think will help people you know make a difference. You can find those at 80000hours.org/covid-19/.

We also just released our annual review for 2019, in case you want to use any extra time you’ve got on your hands on getting to know exactly what we do at 80,000 Hours. We’ll also stick up a link to that, and all of our COVID-19 content, in the show notes.

Alright, without further ado, here’s my colleague Howie Lempel interviewing Greg Lewis.

The interview begins [00:03:15]

Howie Lempel: Today, I’m speaking with Greg Lewis. Greg researches potential catastrophic risks from advancing biotechnology as Acting Head of the Biosecurity Research Group at Oxford’s Future of Humanity Institute. While there, he’s also a DPhil student. He has a medical degree and a master’s in public health from Cambridge, and has worked as a junior doctor and a clinical fellow in public health medicine. Within the effective altruism community, a lot of people know Greg for being an early promoter of earning to give, and for his advocacy on behalf of epistemic modesty. He also recently wrote a problem profile for 80K on global catastrophic biological risks. Welcome, Greg.

Greg Lewis: Thank you. Thank you for having me, Howie.

Howie Lempel: And where are you joining us from today?

Greg Lewis: So I’m enjoying the great indoors in Oxford, which is what I’ve been doing for the last couple of weeks. So far so good. I’m a researcher, so not too much has changed – just the desk I’m sitting at.

Howie Lempel: Fantastic. Yeah. I have recently come out of personal isolation which changes my life essentially not at all. And I am still staying in place in my apartment in London. And so that means that Greg and I are doing this recording remotely. There’s a chance that the audio quality will not be at our usual standards, so I apologize for that. So I guess, just to get things launched off, what are you up to at the moment, Greg? And why do you think it’s important work?

Greg Lewis: Yeah, so I try and do a few things. I mean, principally I’m trying to do a PhD in mathematical biology here at Oxford. But I also get some extracurricular activities as well. One of which is, as you note, I do work at FHI on global catastrophic biological risks, and this comprises maybe a few different things. One is more overarching strategy work, trying to get a better understanding of the risk landscape and which measures have the greatest promise of mitigating these risks. Another is maybe more directly relevant, or maybe shovel-ready things one can do to contribute. This is maybe particularly on my mind given the events around COVID-19. I also try, where I can, to help the emerging community of people in effective altruism and also outside it, who share my concern about global catastrophic risk and are looking to contribute. So that’s a rough survey of what I try to get up to.

Howie Lempel: Great. And can you maybe give an example of what a project might look like in each of those areas?

Greg Lewis: Sure. So at the moment, for my PhD, I’m, in a sense, trying to get a fairly abstract but hopefully worthwhile understanding of the immune system and when it proves to be beneficial and when it doesn’t from an evolutionary perspective, which might give some broader insight into the challenges I try and work on across FHI. For broader strategic understanding, it’s looking at various concepts which are often borrowed from other fields to see if they can be usefully deployed to GCBRs.

Greg Lewis: So one is, which I know my colleagues Allan Dafoe and Ben Garfinkel have done are things called “offense-defense balance”, the idea which is if there’s a conflict between an attacker and a defender, when is this conflict favoring one side or the other in terms of structural factor which might favor one versus the other? And then how does that change perhaps as certain things scale up, which may have some relevance in terms of if the landscape around potential misuse of biotechnology changes, what things were you concerned about? What things can we push on which gives the good guys a robust advantage over the bad guys?

Greg Lewis: With respect to the EA community, I occasionally get referred to people who are early on in their career, who are interested in this area and working out what next steps to take. I also have, as you say, recently wrote a problem profile on this broad area, hopefully to inform people of what this problem looks like, and where they can contribute, and how to weigh it up versus all the other problems in the world. And with respect to any sort of direct projects, there’s like bits and pieces in-house.

Greg Lewis: At the moment, one thing I’ve been looking at is genetic engineering attribution, which is essentially trying to infer from the engineered genetic sequence who was its likely author, which has some potential security benefits if that can be done. I’m working out the policy around that. I’m also trying to think of ways if I can contribute usefully to COVID-19. But it’s a little bit early to say for most of those things how useful or important they will turn out. I guess in some strange sense I’m sort of hoping my work doesn’t prove very important, because the problem I worry about isn’t really a problem after all. I guess we shall see.

Howie Lempel: Yeah. So that’s like a pretty wide range of work. Do you have thoughts on how you came to those priorities or how you prioritize among them?

Greg Lewis: Yeah, so I can give my origin story which is how I got into the broad area; I have a much crisper picture of this than how I prioritize between these things. My hunch is that I’m probably spreading myself too thin, it would be nice to have a sense of stronger focus but that’s, unfortunately as I’m finding, somewhat easier said than done. But with respect to the general point, I worked as a doctor for a bit. Whilst I was in medical school, I was wondering how much good to do.

Greg Lewis: I sort of got into EA via folks like Will MacAskill and a guy called Peter Unger who wrote a book called “Living High and Letting Die”. And I began to apply this mindset to clinical practice to work out, in a sense, how much good does a doctor do? The answer to that was not the most promising. So I thought, “Well, what can I do related to, or instead of medicine, which will have a higher impact?” And I thought public health might be a potentially good option, so I sort of moved into that around the same sort of time, which was around 2012, which is a while back.

Greg Lewis: I was also beginning to be exposed to or interested in longtermism. I also wondered whether there could be a danger; could there be biological threats to this long-term future as well as those which were widely discussed at the time on things like AI? And so that’s sort of how I got into this area. I ended up moving to FHI a couple of years ago, and that’s how I got to where I am now.

Howie Lempel: All right. And so I guess that was the path to arriving at FHI. And so one question is just like, it’s a really big career change. I think most doctors are just not looking to radically transform fields. Do you have a sense of what it was that made you open to making the big switch? Or what felt like it was driving the decision?

Greg Lewis: I’m not entirely sure. I mean, the story I would like to tell about myself would be something like, “Oh, because I’m just so good at trying to do the right thing, I just obviously looked at the considerations and just followed the balance of reason wherever it led me”. I hope that’s mostly true. So I hope I was principally motivated by my judgments on which things seem more or less promising in terms of having a greater or lesser impact. And certainly there are other parts to that, but I don’t have very good insight into what those are. I mean a common suggestion which people have made is I didn’t actually enjoy clinical practice very much, so I was eager for an excuse to jump ship. I don’t think that’s true actually. I actually still miss the patients even now. So I think that’s part of the story.

Greg Lewis: There may be other parts which are somewhat less edifying, which sadly I genuinely don’t know myself, although I suspect they’re there.

Howie Lempel: Did it feel like a hard decision?

Greg Lewis: No, actually. So there are a few things which I miss of what I was doing before. I do miss patient care. But on balance, I do quite enjoy it. There are some personal downsides to working as a clinical practitioner; your nights and weekends are seldom your own. Obviously the work can be quite long hours. It can be quite stressful in various senses. And so from a personal perspective, there are upsides and downsides. But hopefully from, I guess the point of view of the universe if you excuse the term, it’s hopefully much better to be doing the work I’m doing now than the work I was doing as a junior doctor working on a ward for example. So I don’t have many regrets about how I’ve turned out.

Howie Lempel: If you’re up for sharing, are there personal upsides or personal downsides from your current work that you feel are particularly salient or acute for you?

Greg Lewis: Nothing really beyond that. I think I mentioned all the major ones. I mean, the principal upside is just the avoidance of medicine’s taxing, long hours. All the things that you usually talk about in terms of why being a doctor is hard were true to varying degrees in my own experience as well. And so insofar as I’m not doing that anymore, I guess those are, in some sense, upsides. But as I mentioned, on the downside, I did genuinely enjoy it when I was working as a doctor.

Greg Lewis: And perhaps wrongly, but nonetheless did feel sort of like you’re being a little bit of a hero on the wards like, as it were, healing the sick. And I think most doctors grow out of that story after a while, but I think I was still in my fairly naive phase at the time I was leaving it. And so there’s still some like nostalgia around that. But those are the main ones. But as I say, on balance I don’t have any great personal regrets. I think it’s like, on balance, it would’ve been good for my personal life, and, as I said, hopefully good for the wider world as well.

Howie Lempel: Great. It seems like it often works out that way. People, if they feel like they’re doing things that are good for the wider world, you know, often that turns out for them personally too.

Howie Lempel: Yeah. So when you talk about this bit of nostalgia around being a doctor. I know I have some EA friends who are former doctors who have felt a bit of a pull to take a sabbatical from where they’re currently working. And they get into a hospital and start doing COVID responses. Is this a thing that you have either taken seriously, or even just some part of you feels?

Greg Lewis: No, it’s definitely crossed my mind. Especially because I think… Because I left practice a few years ago, the NHS or the GMC, which is the General Medical Council of the UK, has recently re-registered doctors like myself. So I now, in theory, could practice medicine and go again. So I might get various hospitals ask me to, as it were, return to duty. Which obviously, there’s a mix of considerations with respect to that, both personally and more generally about whether that’s a great idea or not.

Greg Lewis: I mean a couple which spring to mind: I last actually touched patient anger, as it were, five years ago. And unfortunately a lot of skills in medicine are pretty perishable. So I’d worry that I’m very severely out of practice, and there’s actually good research on this which I looked up, suggesting that after two years it’s actually quite a lot of effort to get back to where you were. So that’d be like one motivation. There’s also the thing of that given my background has now more moved towards public health and policy and things like that, whether if I was going to spend all my energy responding to COVID-19, whether I’d be best placed as probably a reasonably bad frontline doctor at least at first, versus maybe a somewhat better person working on more like the policy side or similar. But in honesty, I don’t actually have a very crisp idea of how I’m going to address this dilemma, but it is definitely weighing on my mind.

Howie Lempel: Yeah. So COVID-19 is one of the two topics that I wanted to chat with you about. Mostly because Rob and I have rushed out a couple of podcast episodes on the topic recently, and we are both very self aware of not being experts, and so bringing on someone with some background as a doctor and in public health, and at least in adjacent fields, to ask them questions and to show us where we’re wrong seemed really valuable. And then later on, we’re hoping to talk about the global catastrophic biological risk profile that you’ve written up, and the sort of case that you’ve made for working in that area. Does that general organization sound okay to you?

Greg Lewis: Sounds good. I feel almost obliged to say I would hesitate to call myself an expert on probably any of these areas. I mean, to be an expert on COVID-19, generally you’d have to spend like a century of background in all the various areas, which I definitely haven’t done. And there’s actually quite a lot of data which keeps coming out that I fear that by the time this podcast comes to air, it may already be out of date. But I will nonetheless try my best. And GCBRs have this similar property of being fairly pan-disciplinary and also very complicated. So I can do my best, but I wouldn’t want to offer a great guarantee of quality. But I guess it’s for the listeners to decide.

Howie Lempel: A helpful disclaimer. Yeah. So I guess, just give some context, what has your relationship with the outbreak been so far? How closely have you been following it?

Greg Lewis: So I followed it fairly closely. It’s obviously a matter of interest to probably most people on the planet by now. But insofar as I used to work in public health and things related to that, there’s obviously a particular professional interest to try and, as best one can, keep abreast of the relevant things. I also, sort of in the early days, was sort of helping out FHI in working out how the office should best respond to this as well, which provides a further motivation to try and keep track of things. So yeah, maybe like a reasonably well-informed layperson overview I might be able to provide.

What is COVID-19? [00:16:05]

Howie Lempel: Cool. And yes, we’re going to ask Greg to give that kind of overview. For listeners who’ve already had that, totally encourage you to skip ahead. But yeah, so just to give a sense of what is this disease? Where did it come from? How scared should we be of it? I was wondering if you could just catch us up. So maybe to start with, you know, when did this start? Where did it come from? What type of a disease is this?

Greg Lewis: Sure, I’ll try. I should stress that a lot of this area is shrouded in quite a lot of uncertainty. But anyway, COVID-19 is this new infectious disease in humans. It’s caused by a coronavirus, which is SARS-CoV-2. We think this emerged probably somewhere in or near Wuhan, China in late 2019. We think it’s something called a zoonotic disease, which means the virus used to, as it were, infected other species, and then started infecting humans. But exactly which species it originally infected and how it came to start infecting humans is very uncertain. There’s lots of conjectures in the literature, but I don’t think anyone really knows for sure.

Howie Lempel: Do you know how we are so confident that it’s zoonotic?

Greg Lewis: Well some of the evidence that people have been looking at are comparing the genetic sequence of a virus to the genetic sequence of other viruses. And you find quite close matches between this virus and another coronavirus which would infect bats, and I think also pangolins, although I think the relative similarity is controversial. So that’s perhaps one of the main lines of evidence which leads one to suspect that this virus was originally in another species and crossed over to people.

Greg Lewis: It’s also worth noting that this so-called zoonotic transfer, or zoonotic virus effect, in which one species is going on to infect another species, is fairly commonly observed and hypothesized for other emerging infectious diseases. We think this had like a large part of the story to do with things like the Ebola virus, maybe HIV, various pandemic flu strains we think involve recombination in another species and then end up jumping back over into humans. So given that the mechanism isn’t so implausible, and you find these suggestive things when you look at the genome, all of this adds up to be suggestive.

Howie Lempel: Got it. That’s really helpful. Okay, great. So we’ve talked a bit about where the virus started from. Can you talk a little bit about how it’s spread from there?

Greg Lewis: Yes. So obviously this is contagious. We believe that principally it’s spread through respiratory droplets, either directly. So an infected person coughs, and the droplets which are in the air for a little while may be inhaled by those close by. Or indirectly, so someone coughs into their hand, they touch an object, another person who’s not infected touches that object and then touches their face so transferring the virus to them. There have been various other conjectures of possible sources of spread. There’s some suggestion that, on occasion, a virus can be spread by aerosol, although that seems to be like a minority.

Greg Lewis: There’s somewhat a continuum between droplet spread and aerosol spread anyway. There’s also some conjecture that the virus could be possibly shed in feces or stool. So there’s a possibility of fecal-oral transmission. But these are mostly conjectures or cannot be ruled out sort of things, rather than the principle mode of spread which definitely seems to be this respiratory droplet sort of route.

If you end up infected, how severe is it likely to be? [00:19:21]

Howie Lempel: So we’ve talked a little bit about how the disease is spread. If you do end up infected with the disease, how severe is it likely to be?

Greg Lewis: Sure. So assessing severity is quite complicated. One of the key challenges is that for many people COVID-19 seems to give either no illness whatsoever, so no symptoms or very few symptoms, or a reasonably mild disease. Which means you sort of have this iceberg effect whereby the people you see in hospital are sort of the tip of it who are the most severely unwell, and it’s hard to work out from it how many people have also been infected but haven’t had such severity.

Greg Lewis: Maybe like the most widely used data is from a very large, I think 70,000 person study in Wuhan. So we think there’s some fraction who may be asymptomatic. Of those who end up getting recognized as a case, we think about 80% of those are, relatively speaking, mildly unwell with something similar to a flu-like illness with a fever, tiredness, or a dry cough. Of the remaining 20%, 15% are more seriously unwell and require hospital care of varying types. And 5% are critically unwell, and so might require things like mechanical ventilation or other signs that they are very severely sick.

Greg Lewis: The so-called case fatality rate is what portion of these people die. And for that, you get figures from, I think, 1% to 3% if you estimate based on the cases you see. The challenge of that is that isn’t quite the same thing as the infection fatality rate, which is possibly the question you’re more interested in. And so conditioned on me being infected, how likely am I to die, is sort of the question we care about more than if I’m infected and I’m recognized as a case, how likely am I to die?

Greg Lewis: And to try and adjust this, it’s quite tricky. On the one hand, all those people who are currently known to be cases, you don’t know how all of them will turn out, so you can’t necessarily just assume that everyone will recover and survive. Well obviously you definitely hope they do. And, on the other hand, given this iceberg effect for these subclinically ill asymptomatic people, you also don’t know what the denomination really should be. And there’s been various attempts to adjust this based on various sources of data, and probably the best source, or the best source I rely on, is an Imperial study. One of like the 12 reports they’ve done so far, which estimates the infection fatality rate of 0.9% with quite a lot of uncertainty.

Greg Lewis: It’s also worth addressing that this risk isn’t uniform across a population. So the risk of death is much lower if you’re young and healthy. To my understanding there’s been no one who’s died from this disease under the age of 10, and I certainly hope that’s true and continues to be true [Alas no longer true, given some case reports – Ed.]. But by contrast, the infection fatality rate they estimate for people who are over 80 years old is around 9%. So that’s obviously 10 times higher than the rate across the population. We also think that preexisting conditions of various sorts would also increase one’s risk as well, both probably of getting more severely unwell and also unfortunately of dying too.

Howie Lempel: Okay. So it seems like you’re taking a lot of your intuitions on this from this Imperial report that estimates an infection fatality rate of around 0.9%. As you said, these vary across contexts. Do you know what context that was attempting to model?

Greg Lewis: Yes. I think this was, to my recollection, modeling as it were a status quo scenario. So maybe it’s easier to stress what this may be sensitive to. So one area which it maybe proves to be higher or lower, is it depends on, in a sense, how good can you treat people who get unwell? And so, for example, if we get new developments in how to better treat people who become sick with this, then you’d expect the IFR to go down. Contrariwise, which is a major worry confronting a lot of policymakers right now, is if your hospital services become overburdened. So if there’s a lot of people who are very unwell at the same time and you have limited capacity and you can’t treat all of them, this will probably contribute to excess mortality.

Greg Lewis: Another concern is that may not just apply to people who are sick with COVID-19, but also people who get sick for other reasons during the same period. So people with heart attacks or strokes or other serious medical conditions. If they’re having to seek care in an environment where already hospital services are greatly overburdened, you’d expect unfortunately them to receive less good care and a worse outcome as a result of that.

Howie Lempel: Got it. Good point. And then I guess one thing that I’ve noticed in these types of discussions of severity is that it’s really easy to get anchored on the fatality rate numbers. And so I’m wondering… I guess number one, whether you know anything about morbidity from COVID. Like how much of an effect we think that ought to have. But also, we hear about these enormous numbers of people who maybe might not end up in an ICU, but who end up spending a bunch of time in a hospital bed. Do you have any sense of what’s going on with those folks?

Greg Lewis: Maybe. I mean, so with respect to morbidity, COVID seems to present as like an acute illness which then people recover from. Obviously a concern has been raised on, could there be chronic long term effects? So even though you recover from the infection, are that some consequences for your health after you’ve recovered? And that’s unfortunately very hard to know for sure because no one’s been followed up for this disease for more than three months. There are like a variety of factors you can speculate upon, which could maybe increase or decrease your estimates. So obviously there’s been some observation of chronic health effects of people who were infected with SARS, which is somewhat related. In contrast though, other coronaviruses, like the common cold, don’t really have very significant long run effects. And then there’s other things you can deduce from, like, for example, if it was an acute infection, which seems to get cleared so people have negative PCRs. Sort of it’s suggesting they’ve got rid of most of the virus, is not what you’d typically expect for a virus which causes an infection and then causes chronic consequences thereafter. Although unfortunately, as I’m maybe indicating, nothing can crisply be ruled in or ruled out. There’s also potentially an effect where both you become very severely unwell, it may take you longer to recover, and maybe there will be some long term consequences of that as well. But all of this is unfortunately no better than conjecture either way. We’ll find out more as time goes on.

Howie Lempel: Got it. Makes a lot of sense.

How does COVID-19 compare to other diseases? [00:25:42]

Howie Lempel: So you’ve done a good job characterizing the basic situation and sort of lining up what this virus looks like, and I think it’d be helpful to contextualize it a bit. So you can think of, like on the one hand, you hear comparisons between COVID and the seasonal flu often from people who are least concerned. And then on the other hand, you might say like, “Look, this is the biggest pandemic that the world has faced in a while,” and kind of go pretty far on the other side and start to worry like, “Is this going to be like a serious global catastrophe?” And I’m curious, especially because you study those incidents sort of all the way on the end of that curve, like how you think about where COVID fits in?

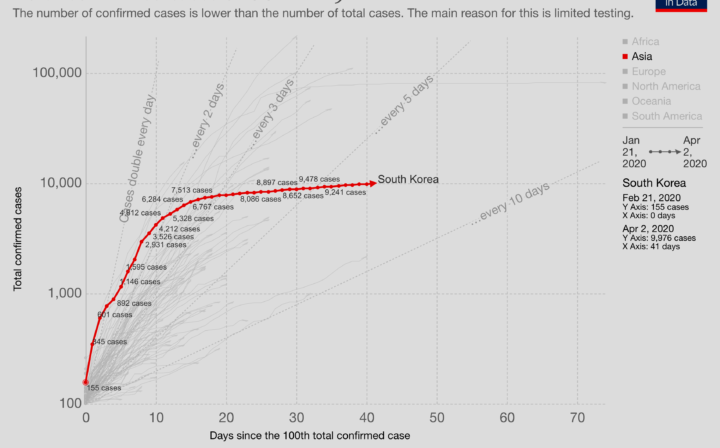

Greg Lewis: Sure. So I think it has been very unfortunate that people have suggested it’s similar to seasonal influenza. Although seasonal influenza does share some features with COVID-19, it’s much less severe in terms of how many people it makes severely unwell. How many people end up dying from it, and so on and so forth. So it’s definitely substantially worse than, as it were, the typical flu season. In terms of how to rank it out on the tail of very bad events, people making comparisons of, say, the worst pandemic since 1918 is sadly, I don’t think, hyperbolic.

Greg Lewis: It’s still hard to compare pandemics to each other because the data we get from this one is firstly very uncertain and we’re not entirely sure, for example, how well will the measures to address it or contain it work, and it’s also actually very hard to figure out historically how bad some pandemics were, on which I suspect more later. But it seems, at the moment my best guess would be that this seems to be worse than other influenza pandemics we’ve seen over the course of the 20th century, with the exception of 1918. And so it seems like the worst since then is unfortunately a reasonable guess.

Greg Lewis: In terms of, as it were, does this count as a global catastrophic biological risk? Then in the colloquial use of these terms it definitely does. So it’s definitely a global catastrophe which is biological. The only one which doesn’t really apply is risk, because it’s already happening. It’s not really a risk anymore, unfortunately. But typically, and again, maybe more later, the way this term is used in the literature is sort of events which are so bad that they pose a credible threat to human civilization as a whole, roughly speaking. I don’t think really any historical pandemic has really posed such a grave risk, notwithstanding that they are humongous and outrageous humanitarian catastrophes. And thinking back to something like the Black Death or the 1918 flu, COVID-19, which I don’t think will become as severe as either of those two things, I don’t think it’s like a GCBR either in that sense.

Howie Lempel: Got it. So yeah, I think it would be interesting to talk through some of those historical pandemics just to get a sense of what could happen without rising to the level of it being a GCBR. But maybe like another way to just sort of get calibrated on like how big of a deal this is. People have been talking about how we haven’t seen anything like this since the Spanish flu. This is like a once-in-a-century event. Does that seem accurate to you? And how surprised were you that something like this happened? Is this like a big update for you on how bad pandemics can get, or how frequently they arise?

Greg Lewis: Sure. So I think calling it sort of like ‘worst since 1918’ is reasonable. I mean it’s hard to say. Maybe as one hopes, we’ll see this great reduction in the current exponentially increasing trend of infections and deaths, such that it turns out to be much less bad than something like the 1918 flu. But unfortunately it’s still too early to say. In terms of, was I surprised by this? I definitely don’t want to claim I’m some sort of Nostradamus who predicted to the day or the hour that there would be a major pandemic which would cause a grave humanitarian catastrophe. Unfortunately, I do think that a lot of people working in the areas like public health, pandemic preparedness, epidemiology, have been stressing for a very long time that we remain very vulnerable to a pandemic, to emerging zoonotic diseases. Various things we’re doing probably increase the risk of these diseases arising. And we have very limited means of, if it does happen, to respond to it in a way which would like dramatically reduce the suffering and death it would cause.

Greg Lewis: And so I think, in that sense, it’s maybe somewhat depressing that this wasn’t exactly like a bolt of lightning from a clear sky. People were saying there were clouds on the horizon for years and years and years. I mean, CHS had a tabletop exercise discussing how an emerging pandemic could cause lots of problems, and these problems we’re unfortunately basically experiencing now. I mean Bill Gates had a TED Talk a while ago saying we’re not ready for the next pandemic, and unfortunately it seems like he was right. And you know, if you look at most people who’ve been writing on global health security for quite a long time, they’ve kept stressing, “This is a serious risk. We’re not sure when, but it’s probably a matter of when rather than if. And if it does happen, we’re going to be a lot of trouble”.

Greg Lewis: And so in that sense, unfortunately, this wasn’t a great surprise, and for that reason it’s not been a ginormous update for me, because I already thought it was going to be a pretty big danger, and the danger happening doesn’t really do much to change that. Another challenge here actually, which may also come up later in the program, is these events are rare and so getting like a very good sense of the evidence of a single event is very hard. Reality, I guess, is somewhat underpowered to assess whether, let’s say, the rate of pandemics is increasing or decreasing over time, especially given all the challenges in trying to assess all the evidence, and we don’t observe things very well.

Howie Lempel: Yeah, cool. So I guess the takeaway is this is a pandemic serious enough to be a candidate for a once-in-a century-event, even if things are still early. And we certainly have some hope that things will end up looking better than we expect, and also that the public health pandemic preparedness community, while they’re not fortune tellers, they have been concerned about this kind of thing for a reasonably long time. Does that sound like a fair summary?

Greg Lewis: That seems fair to me, yes.

Common confusions around COVID-19 [00:32:02]

Howie Lempel: Great. So I guess maybe moving on, there are, I guess, specific questions about characteristics of the virus and the disease that seem to come up over and over again, where I haven’t been able to get an answer that I feel like I really understand. So shooting it by a former doctor and seeing how that goes just seemed like a good opportunity. So you are not going to be an expert in all of the things that I bring up, but I wanted to see if you were game to sort of go through some of these?

Greg Lewis: Sure, I’ll try. I’m not actually a former doctor yet. I am still on the medical register, just about. I mean, we’ll see if what I say in the next few minutes may cause that change, but I’ll try my best.

Howie Lempel: Great. Yeah, so one concept that comes up repeatedly is that a lot of our data could be biased, or inaccurate, or not measuring exactly what we want because it’s not picking up cases that are asymptomatic or mild cases. And so if you have cases that range all the way from like, “I feel nothing,” to, “I’m in the hospital,” to like, “I am in critical condition” or “dead”, and then only the people who get hospitalized and actually are becoming clinical cases, you’re going to look like all of the cases are really severe. So it matters a lot to figure out how many mild cases, how many asymptomatic cases are out there. So do you want to talk a little bit about anything else that’s relevant about these categories, and why they matter in outbreak response and epidemiology?

Greg Lewis: Of course, I’ll try my best. So one challenge is it’s sometimes hard to distinguish between asymptomatic and presymptomatic. So someone may test positive for a virus before they do have symptoms. They do eventually go on to develop symptoms. And so trying to work out how many people, as it were, remain asymptomatic with this infection is pretty fraught. There’s various data sources you can use, like repatriation flights, the Diamond Princess which is this cruise ship where a lot of people had an outbreak on where we tested most people – almost everyone. And so there’s various attempts like this, but all of them are challenging, because you want to adjust to lots of things when you’re doing this. But it suggests that some proportion of people we think probably remain asymptomatic. And that may also vary by age. We’re not entirely sure.

Greg Lewis: The other challenge is whether people can spread the disease before they develop symptoms. So, as it were, asymptomatic spread. And unfortunately that seems to be very likely, which does pose a big challenge for containment because if you can isolate people who are sick, that gives a better chance of containing it if you isolate all the people who are sick. If some people who think they’re healthy but are, in fact, infected can spread to someone else, who then does become very sick themselves, that poses a much greater challenge.

Howie Lempel: Yeah, so I guess I’ve just always been curious about why there’s so much variation across viruses. Where for some viruses it seems to be the case that asymptomatic or presymptomatic people are actually doing a bunch of transmission, and then for other viruses it’s not until they start showing symptoms, or even like a couple of days into showing symptoms before they start infecting other people. And I was wondering if there’s any sort of known mechanism for why there’s this variance of why this took place?

Greg Lewis: Yeah, so I mean maybe one way to put it is that depending on the mode of spread, you are releasing, to some degree, respiratory droplets just when you’re talking, as well as when you’re coughing or sneezing. So there’s a plausible story whereby if a virus is replicating away but it’s yet to cause you any symptoms, you may still be spreading it without having symptoms. In terms of why some infectious diseases do this more than others, and to varying degrees, I don’t have a very good answer, I’m afraid.

Howie Lempel: Cool. Does that mean that I should be at all more worried about coming into contact with people who are just speaking distance away from me? And I’m having a conversation with them and they’re not coughing. I feel like the sort of general vibe that I’ve been getting is very centered on like, “Don’t get coughed on”.

Greg Lewis: Yeah. So a lot of the physical distancing recommendations you’re seeing from various governments, including my own in the UK, is essentially trying to act as an insurance against this risk of people spreading it to others without either person realizing they’re at risk. So, in a sense, this idea of like, avoid all non-essential contact with others, doesn’t have a rider of like, “Oh, if both of you feel well it’s fine,” partly for reasons like this. But also people may not always recollect what symptoms they have. If you’re coughing like once or twice a day or something, maybe that’s a sign of a very mild infection for argument’s sake. But you may not notice that, potentially, and think you’re well. And so given all these things, there’s this general urge towards just basically making as little in-person social contact as possible as a way of reducing the spread of the disease.

Greg Lewis: If you knew for sure that only people who were having symptoms could spread it, which may have been the case in SARS, although there’s slightly more of a story there, then maybe this wouldn’t be as necessary over and above a milder principle of, “Please isolate when you’re feeling unwell”. But unfortunately that doesn’t seem to be the case, and hence why we’re seeing what we’re seeing now.

Howie Lempel: So another question on these asymptomatic cases is that I’ve now seen a lot of work trying to use fairly sparse data to figure out what percent of infected people with COVID are asymptomatic. And I feel like when I start trying to use data sets that I don’t really know well, I’m not a doctor, or an expert, or an epidemiologist, or a virologist, It’s sort of easy for me to end up doing crazy stuff. So it’s just interesting to me to have some sense of like, what is normal? Like, would it be really weird if half of all infections for a disease this deadly ended up being asymptomatic? Like how would that compare to stuff like the flu?

Greg Lewis: Sure. So I don’t think it’s wildly crazy and wildly surprising to see a very wide spectrum of severity, from things which kill, to infections which people may not even notice they have. So, for example, we know seasonal flu kills a reasonably large number of people every year, yet we also think that maybe, I mean there’s like a review on this… So like 15% of cases of infections of the flu may be asymptomatic. So you’re spreading the entire range there. And so in light of this, seeing this very large variation of a condition which can also kill but also be asymptomatic, it doesn’t seem wildly surprising. Obviously the relevant proportions in each of these buckets of like mild, severe, critical, fatal, asymptomatic could vary a lot, but that you can get all of them at once doesn’t seem very shocking.

Howie Lempel: And do you have any idea of what leads to this very wide variation among patients who are all infected?

Greg Lewis: Yeah, that question’s probably a little bit above my pay grade, but I’ll give it a stab. So there’s probably a lot of factors which intervene on your prognosis: so how the disease will happen based on the individual. And that could be based on things like the initial infectious dose, which is thought to be particularly one worry, potentially where people who work in healthcare, because they might have much larger doses than typical. There’s also considerations around how fit and healthy the person was initially. It’s fairly common in medicine that an infectious disease which causes typically mild illness in one group causes much more severe illness in another for all sorts of reasons related to the patient’s physiology and other things like that.

Greg Lewis: So yeah, as I’m suggesting, it’s like you can noodle around a variety of factors. So in terms of explaining the variance, it’s not necessarily very easy to do, but in terms of that there is such a wide variance, that isn’t so surprising.

Howie Lempel: And then I guess one of the things explaining the variance is age, and you can just see a really large effect there. And I’m wondering if there are theoretical reasons to expect fatality rates to vary by age that much?

Greg Lewis: Sure. So I can offer some stuff I was told in medical school. I’m not sure how much this was expert conjecture versus established fact. But we know that age, for many diseases including infectious ones, tends to be a statistical predictor of outcome. So people who are older tend to have a higher risk of getting more unwell or dying. For a majority of things. In fact, age is often used in various scoring criteria doctors use to try and predict the severity of prognosis from various infectious diseases.

Greg Lewis: Now the reason why that’s the case could be a couple of things. One is that age often correlates with other conditions one might have. So maybe your lungs don’t work as well. Maybe you may have heart disease. You may have some kidney trouble, or other things like this, which may mean that if, in a sense, your body isn’t working as well as it could, but if it faces a further insult or a further challenge, it may respond less well then so it doesn’t have these things. So in a sense, age is being confounded by comorbidities. But there’s also a story whereby it could just contribute even if that’s not true. So my understanding, although I’m definitely not a gerontologist, is that most organ systems, even if they don’t get clinically recognized as one gets older as being worse, are in fact becoming less efficient and less highly performing as time goes on.

Greg Lewis: So for this reason, even if it’s not recognized you have these deficits, as it were, you do, in fact, typically still have them. And in virtue of which, even if you’re aging relatively healthily compared to a younger person, you may still be at higher risk if you have a threat to your health than otherwise. So I guess, in a soundbite, age may only just be a number, but it’s also a number which probably correlates quite well with general physiological functioning, and unfortunately negatively so.

Howie Lempel: Another question that’s come up a lot, especially among current policy debates, is a bunch of questions around immunity. There are questions like, “If someone gets infected, how likely is it that they can get reinfected again, and at what points”? And so, there are some claims out there that are saying things like, “Someone tested negative on a PCR diagnostic machine. Then, a couple of weeks later, they come back, they test positive. Uh-oh. Maybe that means that immunity doesn’t last that long and people can get reinfected”?

Howie Lempel: The reason that this might be really scary is if one of your end goals, potentially, is to achieve herd immunity, where enough people become immune that the disease can’t really continue to spread out that much more, that doesn’t work if everybody loses their immunity. I guess I’m curious about whether you have a take on this; does this pass the initial tests of “This seems plausible. This is a way that lots of viruses work”?

Greg Lewis: Sure. I’m definitely not an immunologist either – there’s many things I’m not, unfortunately. But I can channel those who have looked at this. So, my understanding of what they say is the immunology around COVID-19 is obviously deeply uncertain. That being said, I think most people think in typical cases, I know there’s some exceptions to various other conditions which can be pre-existing as well, but in a typical patient, rapid reinfection seems pretty unlikely. There’s, I think, some animal studies I remember seeing a preprint of which suggested they do maintain, as it were, immunological memory. Once they’re infected, they can get rapidly reinfected again. How long this will last for is obviously deeply uncertain, and so I think people typically would want to offer alternative explanations for these accounts of like, “Oh, they tested negative. Then they tested positive again”. Maybe one of the leading ones being that PCR tests are not perfectly sensitive, and so you give that a false negative result rather than if they truly didn’t have the infection and they picked it up again very shortly thereafter. That’s typically the account people would give, which seems roughly right to me.

Howie Lempel: Right. So another big area of uncertainty for me is I’ve seen some claims that even if you end up sick with COVID and get better, there might be some long-term effects that you’re sort of stuck with for a longer period of time. So chronic fatigue is one that’s mentioned a bunch. Lung damage is another one that’s mentioned. And I have not normally seen these from super rigorous sources that are citing many studies. And so I just don’t know whether or not I should put some weight on these and be worried about this, or treat this as just incredibly unlikely. Do you have an intuition on this?

Greg Lewis: I have a few. I mean, so basically the challenge is, we haven’t followed anyone up for more than three months, which means you can’t really know for sure what any long term effects could or could not be. And so you’re left with trying to adduce from other nearby diseases or other nearby circumstances and try and work out how likely it is. And then you get a very mixed picture. I think with chronic fatigue, we know it comes from people who were infected with SARS, which is somewhat similar to COVID-19, at least genetically. But also, COVID-19 is sometimes like cold viruses which cause common colds, which typically don’t seem to be a major worry in terms of chronic results thereof. It seems reasonably intuitive to me that if you become more severely unwell, that increases the chance both of prolonged recovery, maybe a higher risk of what you might call lasting damage. But again, that is only conjecture.

Greg Lewis: Another thing to say is we might also care about the severity of what the long-term effects actually are. So we’re finding a fair amount about whereby infection with some disease or another may increase one’s risk of something or another later in life, but that may not be something which should hugely keep one awake at night. I mean, if we discover like 20 years hence, COVID-19 infection doubles your risk of a one in a million rare form of cancer, this is a long-term consequence, but may not be a long-term consequence we’re particularly worried about. I mean, for myself, the main thing I’d be worried about if I was infected would be the acute illness, even though that is happily for me a pretty low risk even if I do become infected. That’d be the bulk of my worry, rather than this possibility of, well, I could recover and maybe there’s something down the line which causes me trouble later on. But as I’m hopefully making clear, this is unfortunately all pretty much unknown.

Howie Lempel: Well, it’s good to get that summary and I think I’m going to ask that we move on to start talking about the response to the outbreak.

What types of interventions were available to policymakers? [00:46:20]

Howie Lempel: So I guess once the outbreak started, if you could just talk through what types of interventions were available to policymakers and public health officials?

Greg Lewis: Sure. Maybe I could subdivide into what you might do for an individual patient versus what you might do for an at risk population. So, as unfortunately was noted also quite early on, when you have this new emerging infectious disease, your options for a patient are pretty limited, and your options for populations are similarly so. So, you tend not to have any treatments. You don’t have a vaccine. So, you’re fairly stuck with a variety of essentially non-pharmaceutical interventions. So, for individual patient care at the moment, it essentially remains supportive. This is things like oxygen therapy, mechanical ventilation, other things to try and keep patients as well as possible so that they can eventually recover from the infection and clear it themselves. There are a lot of ongoing trials looking at whether we can repurpose drugs, because they might turn out to be useful in terms of COVID-19, even if they weren’t designed with that in mind.

Greg Lewis: For protecting the population, you don’t have a vaccine and you won’t have one for some time, on which I suspect more later. And so you’re stuck with fairly old fashioned public health measures: things which wouldn’t be particularly surprising to a 19th century public health physician. So things like sanitation, improving hygiene, quarantine and isolation, contact tracing. We are seeing people try and augment things with sort of more 20th, 21st century technological tools. But as I think we’re all observing now, it’s difficult to adequately protect the population from the spread of this disease, whilst also allowing them to continue living their lives as they usually would. It seems like a reasonably hard to navigate trade-off.

Howie Lempel: That sounds right to me and does seem to describe one of the big trade-offs here. So I guess one thing that, in my mind, has really framed thinking about the response is that you sort of have this potential pot of gold all the way at the end of the process where in some amount of time — it seems optimistic to consider maybe 12 to 18 months — you’ve researched, developed, manufactured enough vaccines to make them very widely distributed. And then hopefully the pandemic is over. And I feel like the big question there is just why does it take 12 to 18 months? And it seems like a lot of the other interventions are, in part, trying to buy time to get to that point. So yeah, do you have a sense of what parts of this process mean that we’re waiting many months to like a year and a half, instead of responding much more quickly?

Greg Lewis: Sure. So, it’s worth stressing that 12 to 18 months would be fairly fast. It’s almost unprecedentedly fast by typical vaccine timelines. So the question is why does it usually take so long, perhaps? And maybe one way of looking at it is to go through the stages one might do to develop a vaccine and manufacture it. And maybe that would give some insight as to why this might take a while.

Greg Lewis: So the initial step is sort of doing basic science or preclinical work in animals or cell culture. Basically to see if your vaccine does what it’s supposed to do, which is essentially provoke the right immune response. And then once you’ve got something which seems to work in your animal or whatever, you then want to see if it actually is safe to give to a person. And so this is usually what’s called phase one study, which is a phase of study where you give small groups of people vaccinations to test safety. And particularly with coronavirus vaccination, that is a major worry insofar as what we saw in previous attempts to vaccinate against something like SARS was these vaccines could backfire, in that they can actually enhance disease rather than protect against it through a variety of mechanisms, which obviously is very bad. You don’t want to mass administer something that then actually makes people have worse outcomes rather than protecting from it. So that isn’t straightforward to navigate.

Greg Lewis: And then once you do that, you can then run what’s called phase two and phase three trials, where you basically try to test efficacy. Does it actually protect you from the infection? Trials can take quite a while, because you have to maybe follow up for quite a long time to see how much protective effect you’re really getting. I think there was a recent proposal by Lipsitch, Eyal, Smith: I’m mispronouncing their names, I apologize, which is you might be able to say sometime if instead of doing the typical way we do it, which I described just now, you do what’s called a challenge study, which is sort of what you do, as it were, safety and efficacy studies at once on a population.

Greg Lewis: So, this essentially means you give someone a vaccine, and then you give them the agent which causes the infection on a sort of RCT basis and see if it actually does work. Obviously, the ethics issues around that are very fraught, which they cover in their paper, which might be worth having a link. But maybe something worth contemplating in terms of maybe saving you some time. And we do see vaccine challenge studies done in some contexts. I know there’s one for malaria. There’s been other ones as well. But once you get through all of that, and you’ve actually got a vaccine which is safe and it’s effective, you then have to manufacture and administer the thing. Manufacturing often–

Howie Lempel: Just before we get to the manufacturing, so just for the part that we’ve talked through so far, do you have a guess at how long that part is usually going to take?

Greg Lewis: Many months is my best estimate. So doing a challenge study might save you some time. There’s also the risk, of course, that although you’re doing a lot of candidates currently being tested in parallel, obviously some may not work. Some may fall short at various stages. We often can’t back it for major diseases even now. So, it’s not like you can just guarantee success if you go on a vaccine program, you’ll eventually get one. It might take a very long time. So yeah, it’s quite uncertain as to how long it takes you to even get to a candidate in the first place.

Howie Lempel: Got it.

Greg Lewis: So yeah, with respect to manufacturing and administering. The manufacturing is not straightforward. Daniel Gastfriend gave a good talk on the challenge which comes up with scaling pharmaceutical therapies, like making millions and millions of doses very quickly. And that’s often pretty hard. The only thing we really do this for now is with the seasonal influenza vaccine. And doing it for other things is pretty hard. It’s not always very easy to repurpose things. You need to make one vaccine to make another sort of vaccine, for example. It varies a lot depending on what particular vaccine turns out to be an effective candidate. Some may be easier to scale up than others, but generally, the challenges are quite fraught. Probably rather than giving it much more of a summary, I’ll probably just want to refer listeners to the talk Daniel gave at EAG, which I was also sitting in on, which I think covers it much better than I will now.

Howie Lempel: Cool. That makes sense.

Greg Lewis: And I guess one further thing to say, of course, is that administering vaccines worldwide is not an easy thing to do. Vaccine administration is known to be its own series of fraught challenges. You might need a cold chain, for example, which makes things harder, especially if we’re perhaps going to poorer parts of the world. The time it takes once you have the factory churning out, as it were, all the vaccines, getting it into the hands of people who need it may also take more time as well.

Howie Lempel: Cool. That’s really helpful. Two other things that I’m sure are bad ideas and I’m curious whether you know why they’re bad ideas. So it doesn’t seem like they give people convalescent sera particularly early on. Is there a reason that that’s very risky or just not used all the time?

Greg Lewis: So I’m not hugely acquainted with the literature around this. I know it’s actually being, I think, trialed at the moment for COVID-19. I mean, it requires access to their veins. It’s definitely not so easy as vaccination and also… I don’t think it scales, as well. So, I think it could be done and it could be useful. I’d want to think a lot more carefully before trying to survey all the relevant risks and downsides. But even if it does tend to be a pretty effective way of doing things, scaling up, doing it millions and millions of times seems very hard to accomplish.

Howie Lempel: It does sound like a logistical nightmare. And then I guess the other pharmaceutical that you hear a lot about are antivirals. Do you want to talk a little bit about what antivirals are and how they might help?

Greg Lewis: Sure. So, there’s generally antiviral agents, which impedes a virus’s entry into a cell or its replication, or its ability to assemble into viral particles. And generally, although I’m not sure whether we can call viruses living, it sort of interrupts or tries to mess up its life cycle, and so thereby hopefully stops it replicating and thereby helps the body eliminate it. As in most drugs, it often takes quite a while to develop something like this from scratch. So the main focus at the moment is basically just testing a lot of drugs, whether or not they’ve been used against viruses or anything, even infectious diseases, to see whether they show efficacy against this virus SARS-CoV-2. So they test this in the lab and they run clinical trials to assess whether these things actually bring clinical benefit. And I know many of these trials are ongoing. There’s some very early observational data reported from experimental use, but it’s still very early to say how effective any of these things may or may not prove. It’s worth saying, sort of similar to vaccines, even if you do find a drug which does prove to be highly effective – which would, I think, be a dividend of good fortune rather than good preparedness – how easily you can manufacture a lot of it very quickly might vary a lot.