Global priorities research

How would you spend $500 billion?

Every year governments, foundations and individuals spend over $500 billion on efforts to improve the world as a whole. They fund research on cures for cancer, rebuilding of areas devastated by natural disasters, and thousands of other projects.

$500 billion is a lot of money, but it’s not enough to solve all the world’s problems. This means that organisations and individuals have to prioritise and pick which global problems they work on. For example, if a foundation wants to improve others’ lives as much as possible, should it focus on immigration policy, international development, scientific research, or something else? Or if the government of India wants to spur economic development, should it focus on improving education, healthcare, microeconomic reform, or something else? How should it allocate resources between these options?

As we’ll see, there are vast differences between the effectiveness of working on different global problems. But of the $500 billion spent each year, only a miniscule fraction (less than 0.01%) is spent on global priorities research: efforts to work out which global problems are the most pressing to work on.

With a track record of already influencing hundreds of millions of dollars, future research into global priorities could lead to billions of dollars being spent many times more effectively. As a result, we believe this is one of the highest-impact fields you can work in.

This profile is an updated summary of our full research report, for which we interviewed eight people involved with global priorities research.

Summary

Governments, foundations, and individuals spend large amounts of effort and money to improve the world. However, a lot more research could be done to help figure out how to use it best.

Global priorities research can take many forms, using techniques from economics, philosophy, maths, and social science to help people and organisations choose which global problems they should spend their limited resources on, in order to improve the world as much as possible.

Our overall view

Recommended

This is among the most pressing problems to work on.

Scale

We think work on global priorities research has the potential for a very large positive impact. It seems plausible that better prioritisation within international organisations, nonprofits, and governments could help lower extinction risk by between 1% and 10%, raise global economic output by more than 10%, or otherwise considerably improve the expected value of the future.

Neglectedness

This issue is highly neglected. Current spending might be between $5 million and $10 million per year.

Solvability

Making progress on global priorities research seems moderately tractable, though it varies a lot depending on the issues being investigated (with more applied and empirical questions often being more tractable). We’d guess that doubling the resources going toward this issue could take us something like 1% of the way toward the full benefits of better prioritisation.

Profile depth

Medium-depth

This is one of many profiles we've written to help people find the most pressing problems they can solve with their careers. Learn more about how we compare different problems and see how this problem compares to the others we've considered so far.

Table of Contents

- 1 What is global priorities research?

- 2 Why work on global priorities research?

- 2.1 1. Some problems are far more pressing than others

- 2.2 2. We may discover new, even more pressing global problems

- 2.3 3. Billions of dollars could be redirected to more pressing problems

- 2.4 4. Global priorities research is a highly neglected field

- 2.5 5. The field has a track record of success in redirecting hundreds of millions of dollars

- 3 What are the major arguments against this problem being pressing?

- 4 What is most needed to solve this problem?

- 5 What can you concretely do to help?

- 6 Learn more

What is global priorities research?

The field of global priorities research is about rigorously investigating what the most important global problems are, how we should compare them to each other, and what kinds of interventions best address them. For example, how do we compare the value of more work on climate change vs global health vs preventing future pandemics?

We might distinguish between foundational global priorities research on the one hand, and applied global priorities research on the other.

We think both kinds of global priorities research can be very important, and this profile is about both.

Foundational global priorities research

Foundational global priorities research mainly lies at the intersection of economics and moral philosophy, though it may also involve tools from other disciplines. It looks at the highest-level issues concerning which global priorities most further the social good, especially from a long-term perspective. This means it would include topics like investigating the value of reducing existential risk vs other ways of doing good, how much to prioritise ‘broad’ interventions that positively affect many different issues at once vs more ‘targeted’ interventions that focus on a single issue, and what methodologies we should use to answer these questions.

There are also more exotic-sounding topics for foundational global priorities research that nonetheless seem like they might be very important to us — for example: What’s the chance that we are in some sense living in a simulation? Should we try to engage in ‘acausal trade‘?

All these questions are relevant to the issue of which problems we should prioritise working on right now if we want to do as much good as we can, though some are more relevant than others — and the tractability of these questions also varies. To get some sense of the range, see the research agenda produced by the Global Priorities Institute at Oxford, and a few examples of foundational global priorities research questions we’ve collected.

Applied global priorities research

Applied global priorities research also seeks to determine what we should prioritise, but is focused on taking the lessons of the more foundational research and applying them to the particular situations we happen to be in. It often also uses more empirical methods and focuses less on philosophy.

For example, if foundational global priorities research told us that reducing existential risk is a top priority, applied global priorities research might ask which specific risks are biggest and easiest to mitigate (e.g. climate change vs pandemic risk). Or let’s say we wanted to pursue broad interventions — which interventions really do affect a broad range of issues in a robustly positive way? How much do they cost? Another valuable kind of applied global priorities research is investigating an underexplored problem area to see how pressing it seems.

We think many of Open Philanthropy’s research reports represent especially high-quality examples of applied global priorities research.

You also can find lots of great contributions along similar lines on the effective altruism forum — e.g. posts on Growth and the case against randomista development and What is the likelihood that civilizational collapse would directly lead to human extinction (within decades)?. In general, because of its focus on doing as much good as possible with limited resources, applied global priorities research has been a strong focus of the effective altruism community over the past decade.

There isn’t a sharp line between foundational and applied global priorities research; rather it is a spectrum. But very roughly speaking, more foundational research is more likely to be done in an academic setting like the Global Priorities Institute, and more applied research is more likely to be done at a think tank, grantmaking institution, or effective altruist organisation.

Why work on global priorities research?

1. Some problems are far more pressing than others

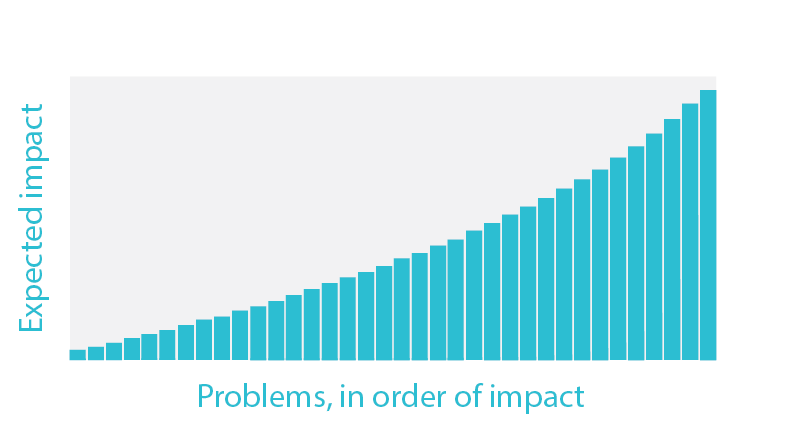

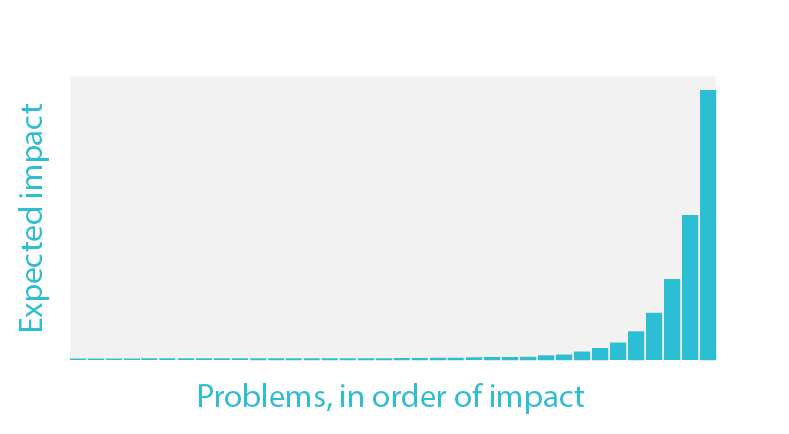

Intuitively, you might think that if we rated the world’s problems on how pressing they are, and put them on a graph, we’d end up with something like this — some problems are more pressing than others, but most are quite pressing:

But when we used our framework to evaluate different problems we found that it looks more like this — some problems are far more pressing than others:

For example, in rich countries like the US or Switzerland, the marginal cost to save a life through spending on healthcare is over $1 million.1 By contrast, the marginal cost to save a life in sub-Saharan Africa through distributing antimalarial bed nets is estimated to be less than $10,000.2 This suggests that if a foundation is focused on health in developing countries rather than in rich countries, it could save about 100 times as many lives.

If such big differences in effectiveness exist, then it is crucial to identify the best areas to focus on. Finding a more effective area could mean we achieve 10 or 100 times as much. Choosing poorly could mean achieving only 1% as much. The aim of global priorities research is to enable decision-makers to avoid this mistake.

2. We may discover new, even more pressing global problems

The differences in effectiveness between working on different problems could be bigger if there are problems that humanity hasn’t even thought of yet. And it seems likely that we haven’t discovered all the serious global problems that exist.

When we look at the history of the human race, we see many examples of major moral problems that most people were completely oblivious to. These include slavery, the deplorable treatment of foreigners, the subjugation of women, the persecution of people who aren’t heterosexual, and the gross mistreatment of animals. It is unlikely that we’re the first generation to have discovered all the serious moral problems that exist, meaning there are probably major global problems we aren’t even aware of today.

Global priorities research could have a huge impact if it identified new pressing problems that we’re not aware of, and redirected money and talent towards working on them.

3. Billions of dollars could be redirected to more pressing problems

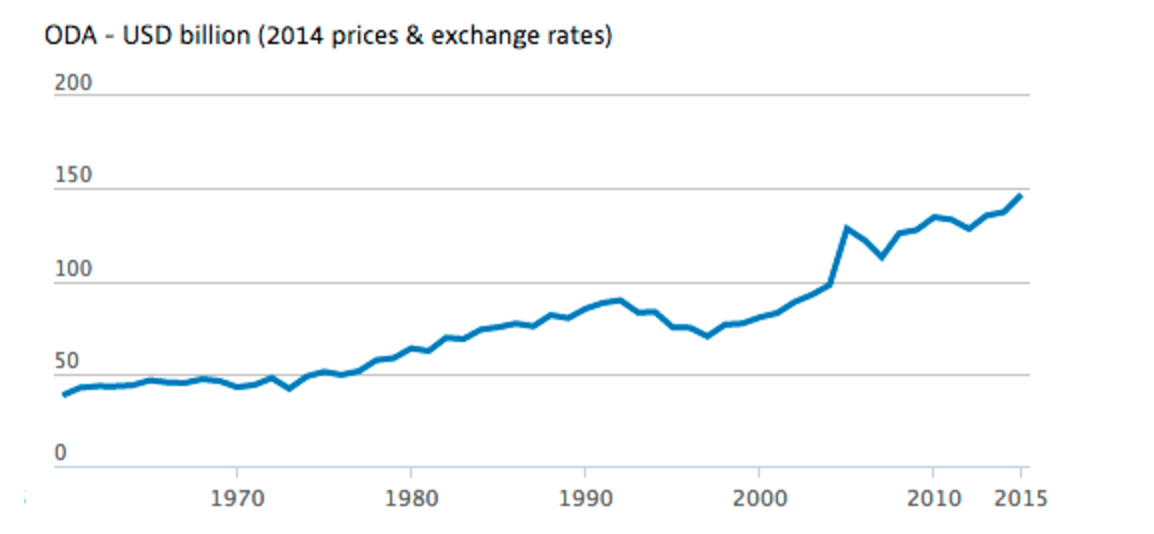

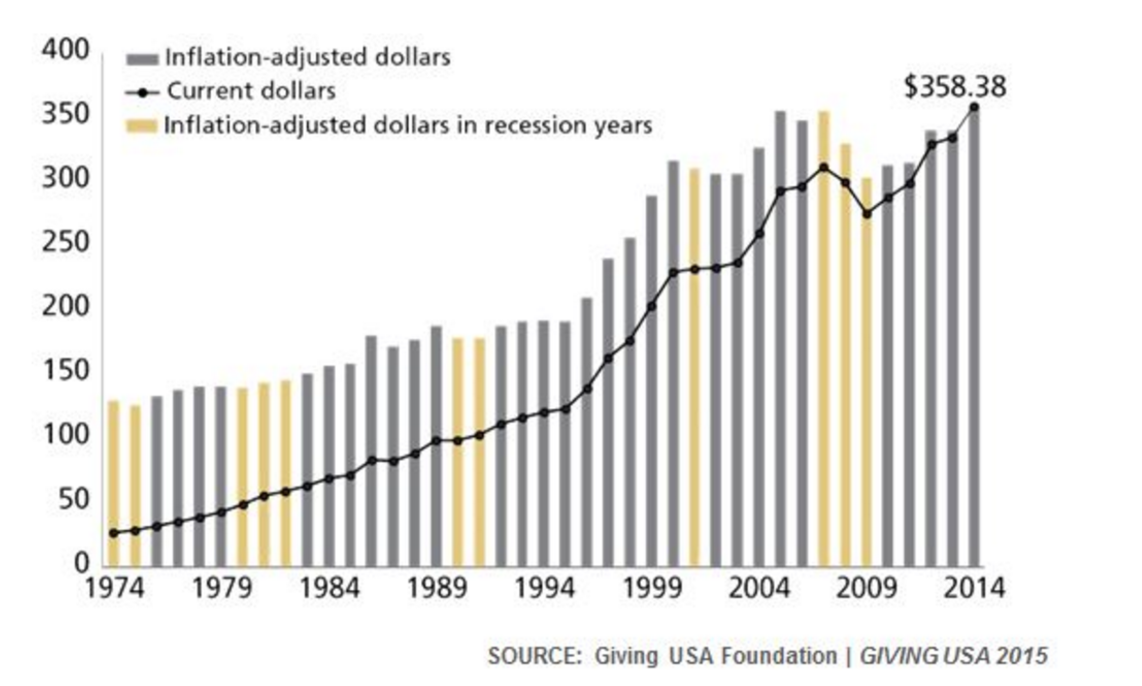

Organisations whose stated purpose is to pursue the common good spend tens of trillions of dollars each year (out of a global GDP of around $75 trillion), most of which is spent by governments domestically. Foreign aid spending is over $135 billion each year, and private philanthropy in the US totals $350 billion each year.

Probably only a small fraction of these tens of trillions of dollars is genuinely intended to improve the world as much as possible, rather than promote the interests of a specific group (e.g. a voting bloc within a specific country). And only a small fraction of that would be responsive to higher-quality research.

Nonetheless, if billions of dollars could be redirected to problems that are larger in scale, more neglected, or easier to solve, this could provide huge gains.

Moreover, many people also want to work on the world’s most pressing problems — that’s why our website exists! — meaning that total resources are even greater than solely monetary totals convey.

And since differences in effectiveness can be so large, even if research only influences a comparatively small amount of resources, it can be highly effective. As one example, the charity evaluator GiveWell produces research which, in 2015 alone, led individuals to give $15.5 million to the highly effective charity Against Malaria Foundation. These donations will likely save around 2,000 lives through the distribution of bed nets that protect people from malaria.3 Only around 4% of US charitable donations go to international causes. This makes it likely that the majority of the $15.5 million GiveWell redirected would have gone to charities working in the US, which, on average, do far less to improve lives than charities working internationally.

4. Global priorities research is a highly neglected field

Despite the importance of this research, it’s also highly neglected. As of 2018, organisations focused on directly comparing different global problems (e.g. farm animal welfare vs nuclear war vs improving scientific research) had a collective budget of less than $10 million per year:

| Estimated budget in 2015 | |

|---|---|

| Open Philanthropy | $2.5 million4 |

| Future of Humanity Institute (fraction on global priorities research) | $800,000 |

| Copenhagen Consensus Center | $1–2 million5 |

| Centre for Effective Altruism (considering only activities focused on global priorities research) | <$1 million |

| Total | $5–6 million |

However, interest in this area is growing, so the total is definitely higher today. We should also note that there is also research being done which indirectly helps with setting global priorities — for example, work done by some academic economists, and groups that run trials and compile data on specific policy areas.

5. The field has a track record of success in redirecting hundreds of millions of dollars

The field of global priorities research is young, but it has already succeeded in influencing how resources are spent. Here are a few examples:

- GiveWell — in 2015 redirected at least $39.7 million in donations from individual donors to their recommended charities.6

- Open Philanthropy — advised the foundation Good Ventures to make grants totaling $76.7 million in 2015.7

- Global Priorities Project — the UK Department for International Development reallocated £2.5 billion (US $3.6 billion) to fund research into treating and responding to the diseases that cause the most suffering. The Global Priorities Project was advocating for this change (though of course the policy process has many inputs, of which they were only a small part).8

- Copenhagen Consensus Center — its cost-benefit analysis helped convince the United States Bush administration to launch the $1.2 billion President’s Malaria Initiative, among many other successes.9

What are the major arguments against this problem being pressing?

The research may be too difficult

You might think that global priorities research will not be able to reach more accurate results than our current best knowledge, due to the large amounts of uncertainty, ambiguity and judgement calls involved. Perhaps the reason this research is neglected is that it’s simply too difficult.

We think this is a reasonable concern. However, the small amount of global priorities research done so far, has already led to significant progress, including:

- GiveWell identifying global health as a promising area to look for outstanding donation opportunities.

- Identifying the importance of taking into consideration the effects on future generations when comparing different global problems.

- The development of better methodologies for prioritisation, like how to assess the value of working on problems of unknown difficulty, for example research into cold fusion, or institutional reform through political lobbying.

Moreover, there are many ‘low-hanging fruit’ opportunities for global priorities research still available. For example, researchers could aggregate expert opinions on the severity of different global problems, and gather existing empirical data on the relative scale, neglectedness, and solvability of different global problems.

The research may be ignored

You might think that politicians and donors won’t be motivated to act on the results of global priorities research. Maybe they’ll care more about securing reelection or will instead respond to emotional appeals and gut judgements.

This is a reasonable concern, but we think that if good evidence is presented, at least some will act on the results, as demonstrated by the examples mentioned above.

What is most needed to solve this problem?

Most needed are researchers, and in particular:

- Researchers trained in economics, mathematics, or philosophy to develop the methodology for setting global priorities.

- Researchers trained in social and natural sciences with the ability to collect data and analyse specific global problems.

Additional researchers can not only enable more progress on these questions, but they also demonstrate that this area is of academic interest, which can bring in more researchers in the future.

Also needed are academic project managers and operations staff to help scale up existing institutes and found new ones.

Finally, it’s less of a bottleneck, but funding is also needed. Funding could be used to scale up and found new research centres. It would also be useful to fund scholarships for individuals, and it would be ideal for one or two funders to specialise in evaluating research proposals in this area.

What can you concretely do to help?

Want to work on global priorities research? We want to help.

We’ve helped a number of people formulate their plans on how to work on global priorities research. If you want to work on global priorities research, particularly if you could get into or are in a relevant graduate programme:

How to enter

If you want to work in this area as a researcher, you’ll need training in the relevant disciplines.

- If you are an undergraduate, you can major in or take classes in mathematics, economics, statistics, or analytic philosophy. If you are out of university, you can take online classes in these subjects, for example this introduction to microeconomics.

- In general, for foundational global priorities research the best graduate subject is an economics PhD. The next most useful subject is philosophy, followed by decision-making psychology, scientific subjects relevant to emerging technologies, and topics like public policy, political science, and international relations. People have also entered this field from maths, computer science, and physics. For applied global priorities research, radically different backgrounds could be useful, depending on the specific problems investigated.

- Note that obtaining advanced degrees and positions in many of these fields, such as academic philosophy, can be very demanding and competitive.

- You should read the existing work of organisations working on global priorities research to get up to speed, such as Open Philanthropy’s cause reports.

What are some top career options within this area?

Research paths

The only major academic centre currently focused on this research is the Global Priorities Institute at Oxford, so if you want to pursue this path as an academic that’s the ideal place to work. That said, we expect that other centres will be established over the coming years, and you could also pursue this research in other academic positions.

One downside of academia, however, is that you need to work on topics that are publishable, and these are often not those that are most relevant to real decisions. This means it’s also important to have researchers working elsewhere on more practical questions.

We think the leading centre of this applied research is Open Philanthropy, and the advantage of working there is that your findings will directly feed into how billions of dollars are spent (disclaimer: they are our largest funder). However, you can also pursue this research at other effective altruism organisations. At 80,000 Hours, for instance, we do a form of applied global priorities research focused on career strategy. Rethink Priorities is another great place to do applied global priorities research.

There have also been people who have pursued global priorities research independently, such as Carl Shulman. These researchers often start with blogging, and then take freelance work from donors and organisations.

Non-research paths

If you don’t want to pursue one of the research paths above, you can:

- Work as an academic manager or administrator, research manager, or in other support roles at organisations conducting global priorities research (listed below).

- Take a high-earning job and donate a percentage of your income to fund the research performed by the groups above. Read our advice on how to maximise the amount you’re able to donate.

You can also see roles supporting global priorities research, and some ways to help in addition to working on global priorities research as a career.

Which organisations could you work at?

We know of only a small number of groups doing research that tries to compare global problems at the highest level (e.g. climate change vs global health). Our top recommends here include:

- Open Philanthropy, which advises Good Ventures, a several-billion -dollar foundation, on its philanthropy. See current vacancies. (Disclaimer of conflict of interest: Open Philanthropy is our largest funder.) You could also consider working at their partner organisation, GiveWell, which carries out priorities research within international development.

- Rethink Priorities has research teams in animal welfare, global health and development, and longtermism and existential risk reduction.

- Global Priorities Institute at Oxford is the leading academic research centre focused on this topic (note that our cofounder, Will MacAskill, is a researcher there). See current vacancies.

- Forethought Foundation, where Will MacAskill is director, supports global priorities research through offering scholarships and research fellowships.

Some other relevant organisations include:

- The Cambridge Centre for the Study of Existential Risk houses academic experts studying different risks to human survival, which then facilitates comparisons among them. See current vacancies and subscribe to get notified of new job openings.

- Founders Pledge creates cause reports to help their pledges choose where to donate.

- Happier Lives Institute researches different ways to increase people’s wellbeing.

- Copenhagen Consensus Center brings together top economists to assess which solutions to global problems are most effective, with a focus on international development. However, we have reservations about their work on climate change. See current vacancies and subscribe to get notified of new job openings.

- Global Catastrophic Risk Institute compares different global catastrophic risks.

- Center on Long-Term Risk researches ways to reduce suffering risks especially.

- Future of Life Institute

A wider range of groups run trials or collect and compile data in specific policy areas. We don’t regard this as equally neglected, but it is a very complementary form of research:

- Washington State Institute for Public Policy

- The Pew-Macarthur Results First Initiative

- The Center for High Impact Philanthropy

- What Works Network

- Campbell Collaboration publishes meta-analyses that draw on large numbers of studies to determine the effectiveness of different types of social interventions

- Behavioural Insights Team

- Poverty Action Lab is an academic network that specifically studies the effectiveness of interventions designed to alleviate poverty

- Many other social scientists or medical researchers run trials on ways of improving wellbeing

Find opportunities on our job board

Our job board features opportunities in global priorities research:

Where can you donate to help global priorities research?

You can donate to most of the organisations listed above, where currently the Global Priorities Institute seems like the best option (you can donate at the bottom of the Oxford Faculty of Philosophy page). Open Philanthropy isn’t funding constrained.

(To make a tax deductible donation to the Global Priorities Institute from the US, go here, select “Humanities division,” and write

“Global Priorities Institute” in the textbox.)

Learn more

Top recommendations

- YouTube playlist: 23 talks on global priorities research from EA Globals, including an introduction to the field.

- Ajeya Cotra on worldview diversification and how big the future could be

- Phil Trammell on how becoming a ‘patient philanthropist’ could allow you to do far more good

Further recommendations

Research

- See the research agenda produced by the Global Priorities Institute in Oxford.

- Here’s a shorter list of example research questions.

- And check out talks from the Global Priorities Institute.

- For examples of global priorities research, see Open Philanthropy’s cause reports and this series of posts on how to prioritise research.

- Christian Tarsney on future bias and a possible solution to moral fanaticism

- Hilary Greaves on moral cluelessness, population ethics, probability within a multiverse, and harnessing the brainpower of academia to tackle the most important research questions

- Toby Ord on the precipice and humanity’s potential futures

- Will MacAskill on the moral case against ever leaving the house, whether now is the hinge of history, and the culture of effective altruism

- Will MacAskill on balancing frugality with ambition, whether you need longtermism, and mental health under pressure

- Andreas Mogensen on whether effective altruism is just for consequentialists

- Marcus Davis on Rethink Priorities

- Bob Fischer on comparing the welfare of humans, chickens, pigs, octopuses, bees, and more

Other articles and podcasts

- Podcast: Michelle Hutchinson hopes to shape the world by shaping the ideas of intellectuals. Will global priorities research succeed?

- The world’s biggest problems and why they’re not what first comes to mind

- Career review: Economics PhD

- Why the long-term future of humanity matters more than anything else, and what we should do about it, according to Oxford philosopher Dr Toby Ord

- Working in the government you can have a big impact on pressing global problems. Here’s how to get started.

- Career review: Help build the effective altruism community

- The psychologists in the race against collective stupidity and how you can join them

- Our problem prioritisation framework

- Leaders survey: What are the most important talent gaps in effective altruism — and which problems are most impactful to work on?

- Podcast: You want to do as much good as possible and have billions of dollars. What do you do?

- Podcast: Finding the best charity requires estimating the unknowable. Here’s how GiveWell tries to do that, according to researcher James Snowden.

- Why despite global progress, humanity is probably facing its most dangerous time ever

- GiveWell on strategic cause selection

Want to work on global priorities research? We want to help.

We’ve helped a number of people formulate their plans on how to work on global priorities research. If you want to work on global priorities research, particularly if you could get into or are in a relevant graduate programme:

Or join our newsletter and get notified when we release new problem profiles.

Notes and references

- Table 1, Page 60 in Hall, Robert E., and Charles I. Jones. “The value of life and the rise in health spending.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 122.1 (2007): 39-72.

Archived link

Table 3 page 147 in Felder, Stefan, and Andreas Werblow. “The Marginal Cost of Saving a Life in Health Care: Age, Gender and Regional Differences in Switzerland.” Swiss Journal of Economics and Statistics (SJES) 145.II (2009): 137-153.

Archived link↩ - “We estimate that it costs the Against Malaria Foundation approximately $7,500 (including transportation, administration, etc.) to save a human life.” Archived link↩

- GiveWell’s impact page.↩

- “…we spent approximately $3.8 million on our operations, of which $1.3 million was spent on GiveWell’s traditional work and $2.5 million on Open Philanthropy.” Archived link↩

- Conversation with Robert Wiblin on the Copenhagen Consensus Center↩

- Page 6 GiveWell Metrics Report 2015↩

- Page 2 GiveWell Metrics Report 2016↩

- New UK aid strategy – prioritising research and crisis response↩

- Copenhagen Consensus – Our Impact↩