#152 – Joe Carlsmith on navigating serious philosophical confusion

What is the nature of the universe? How do we make decisions correctly? What differentiates right actions from wrong ones?

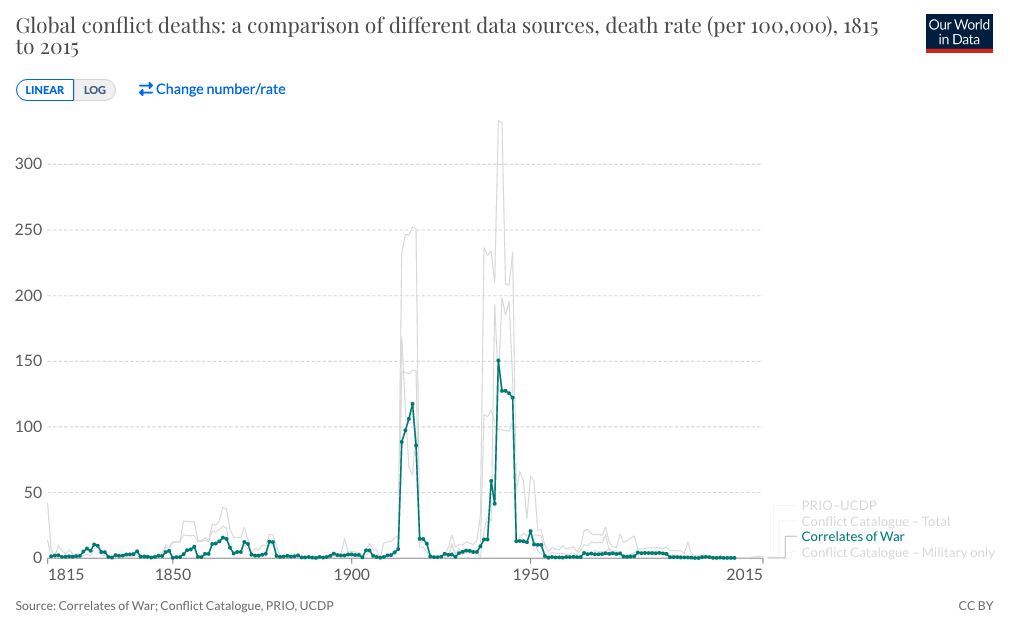

Such fundamental questions have been the subject of philosophical and theological debates for millennia. But, as we all know, and surveys of expert opinion make clear, we are very far from agreement. So… with these most basic questions unresolved, what’s a species to do?

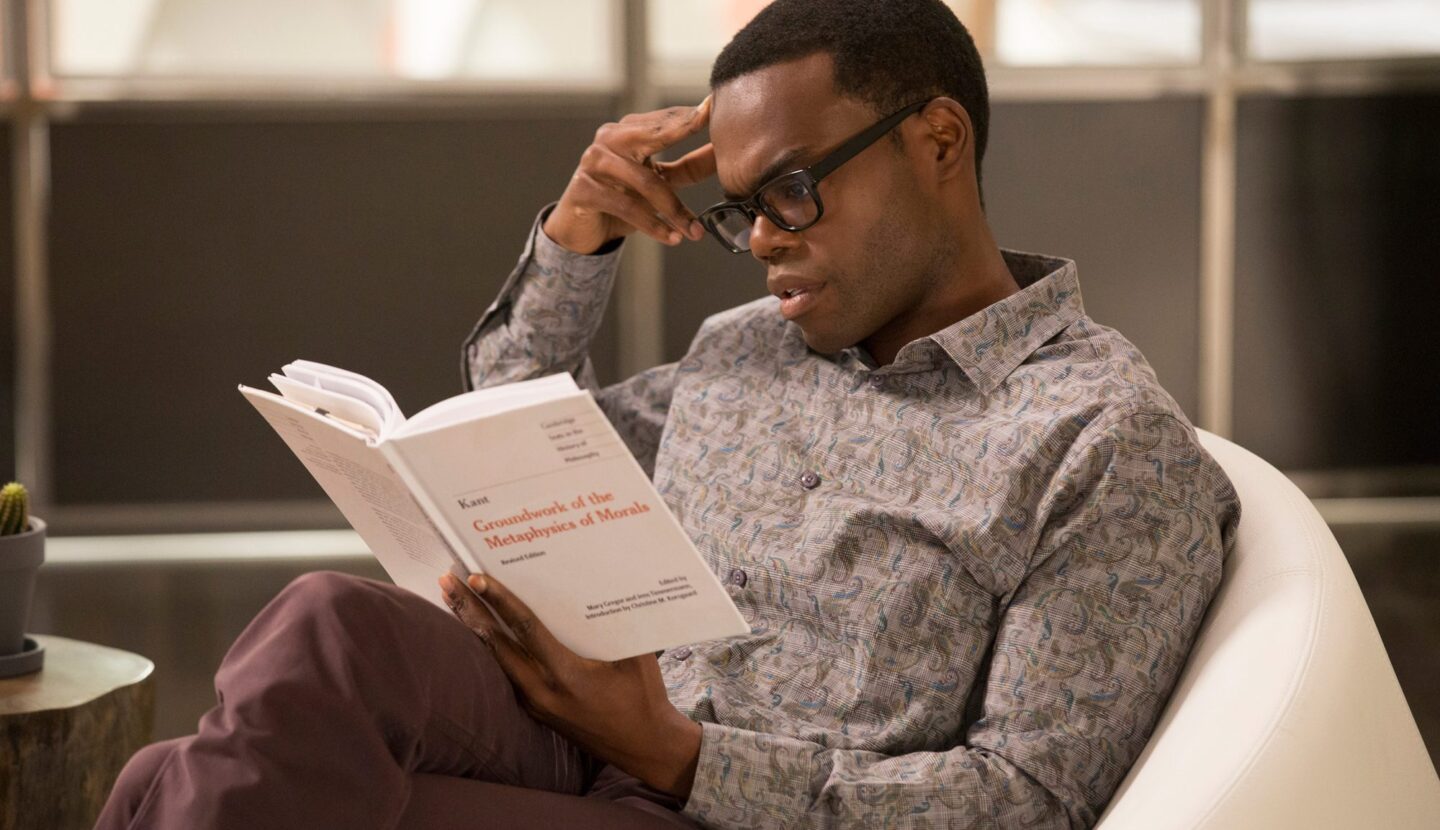

In today’s episode, philosopher Joe Carlsmith — Senior Research Analyst at Open Philanthropy — makes the case that many current debates in philosophy ought to leave us confused and humbled. These are themes he discusses in his PhD thesis, A stranger priority? Topics at the outer reaches of effective altruism.

To help transmit the disorientation he thinks is appropriate, Joe presents three disconcerting theories — originating from him and his peers — that challenge humanity’s self-assured understanding of the world.

The first idea is that we might be living in a computer simulation, because, in the classic formulation, if most civilisations go on to run many computer simulations of their past history, then most beings who perceive themselves as living in such a history must themselves be in computer simulations. Joe prefers a somewhat different way of making the point, but, having looked into it, he hasn’t identified any particular rebuttal to this ‘simulation argument.’

If true, it could revolutionise our comprehension of the universe and the way we ought to live.

The second is the idea that “you can ‘control’ events you have no causal interaction with, including events in the past.” The thought experiment that most persuades him of this is the following:

Perfect deterministic twin prisoner’s dilemma: You’re a deterministic AI system, who only wants money for yourself (you don’t care about copies of yourself). The authorities make a perfect copy of you, separate you and your copy by a large distance, and then expose you both, in simulation, to exactly identical inputs (let’s say, a room, a whiteboard, some markers, etc.). You both face the following choice: either (a) send a million dollars to the other (“cooperate”), or (b) take a thousand dollars for yourself (“defect”).

Joe thinks, in contrast with the dominant theory of correct decision-making, that it’s clear you should send a million dollars to your twin. But as he explains, this idea, when extrapolated outwards to other cases, implies that it could be sensible to take actions in the hope that they’ll improve parallel universes you can never causally interact with — or even to improve the past. That is nuts by anyone’s lights, including Joe’s.

The third disorienting idea is that, as far as we can tell, the universe could be infinitely large. And that fact, if true, would mean we probably have to make choices between actions and outcomes that involve infinities. Unfortunately, doing that breaks our existing ethical systems, which are only designed to accommodate finite cases.

In an infinite universe, our standard models end up unable to say much at all, or give the wrong answers entirely. While we might hope to patch them in straightforward ways, having looked into ways we might do that, Joe has concluded they all quickly get complicated and arbitrary, and still have to do enormous violence to our common sense. For people inclined to endorse some flavour of utilitarianism, Joe thinks ‘infinite ethics’ spell the end of the ‘utilitarian dream‘ of a moral philosophy that has the virtue of being very simple while still matching our intuitions in most cases.

These are just three particular instances of a much broader set of ideas that some have dubbed the “train to crazy town.” Basically, if you commit to always take philosophy and arguments seriously, and try to act on them, it can lead to what seem like some pretty crazy and impractical places. So what should we do with this buffet of plausible-sounding but bewildering arguments?

Joe and Rob discuss to what extent this should prompt us to pay less attention to philosophy, and how we as individuals can cope psychologically with feeling out of our depth just trying to make the most basic sense of the world.

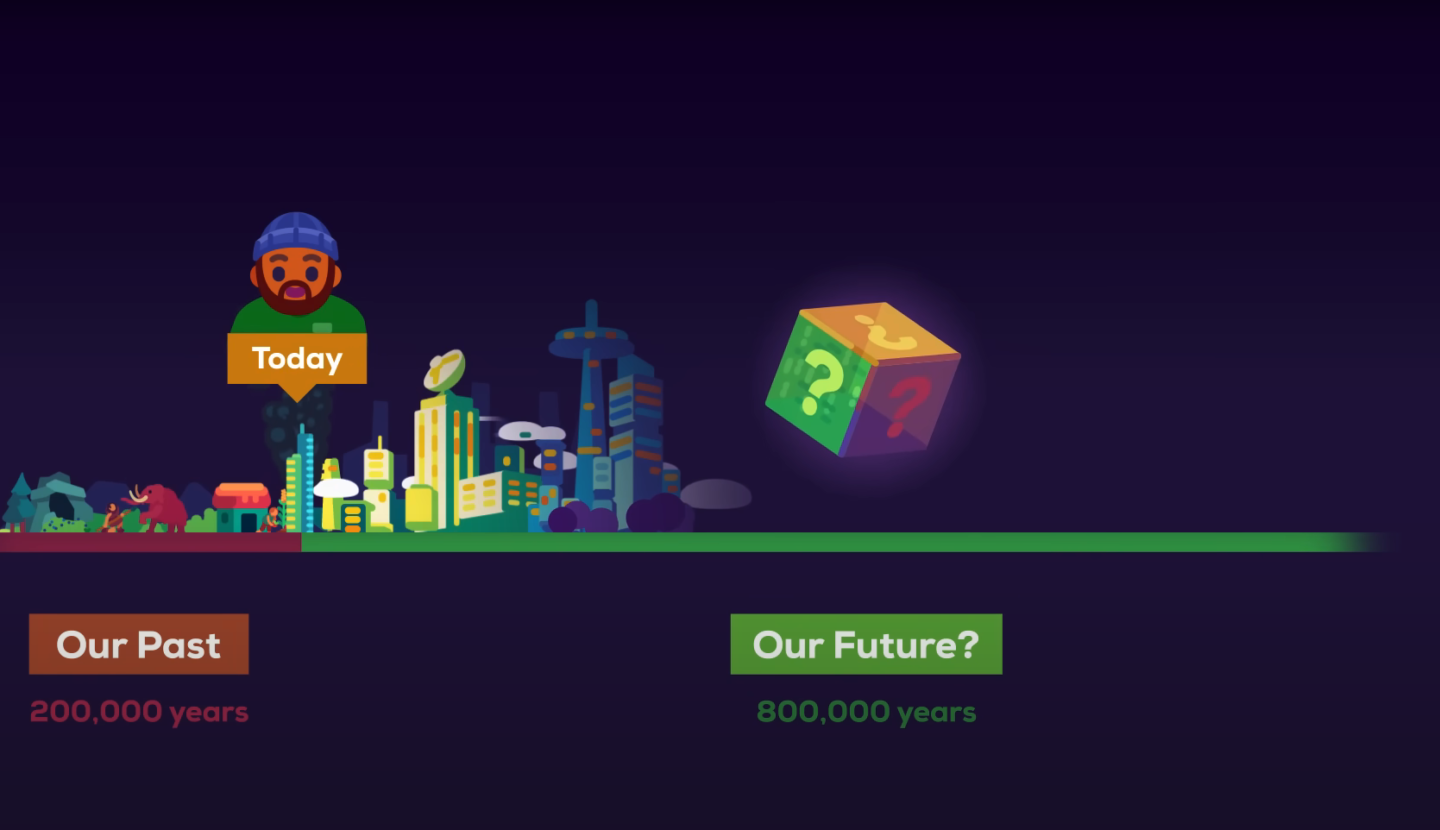

In the face of all of this, Joe suggests that there is a promising and robust path for humanity to take: keep our options open and put our descendants in a better position to figure out the answers to questions that seem impossible for us to resolve today — a position he calls “wisdom longtermism.”

Joe fears that if people believe we understand the universe better than we really do, they’ll be more likely to try to commit humanity to a particular vision of the future, or be uncooperative to others, in ways that only make sense if you were certain you knew what was right and wrong.

In today’s challenging conversation, Joe and Rob discuss all of the above, as well as:

- What Joe doesn’t like about the drowning child thought experiment

- An alternative thought experiment about helping a stranger that might better highlight our intrinsic desire to help others

- What Joe doesn’t like about the expression “the train to crazy town”

- Whether Elon Musk should place a higher probability on living in a simulation than most other people

- Whether the deterministic twin prisoner’s dilemma, if fully appreciated, gives us an extra reason to keep promises

- To what extent learning to doubt our own judgement about difficult questions — so-called “epistemic learned helplessness” — is a good thing

- How strong the case is that advanced AI will engage in generalised power-seeking behaviour

Get this episode by subscribing to our podcast on the world’s most pressing problems and how to solve them: type ‘80,000 Hours’ into your podcasting app. Or read the transcript below.

Producer: Keiran Harris

Audio mastering: Milo McGuire and Ben Cordell

Transcriptions: Katy Moore