Transcript

Cold open [00:00:00]

Toby Ord: Ultimately, in terms of the impact we end up having in the world, you could think of virtue as being a multiplier — not by some number between 1 and 10,000 or something with this huge variation, but maybe as a number between -1 and +1 or something like that, or maybe most of the values in that range. Maybe if you’re really, really virtuous, you’re a 3 or something.

But the fact that there is this negative bit is really relevant: it’s very much possible to actually just produce bad outcomes. Clearly, Sam Bankman-Fried seems to be an example of this. And if you’ve scaled up your impact, then you could end up with massive negative effects through having a bad character. Maybe by taking too many risks, maybe by trampling over people on your way to trying to achieve those good outcomes, or various other aspects.

Rob’s intro [00:00:55]

Rob Wiblin: Hey listeners, Rob here, head of research at 80,000 Hours.

Interviews with philosopher and mathematician Toby Ord are always super popular, and to be frank, he makes my job as a host really easy, so I’m always looking for an excuse to bring him back on.

And I got one when on YouTube I saw his keynote presentation to an Effective Altruism Global conference that happened back in February.

Toby goes over three little-discussed reasons from philosophy why it’s a bad idea to go all-in on pursuing any particular goal at the expense of everything else, which are obvious to me in retrospect but I hadn’t really thought enough about.

As he explains in the conversation, Toby had looked at this topic before, but was motivated to dig into it and write about it again because of the possibility that Sam Bankman-Fried, who stands accused of committing serious fraud while CEO of the cryptocurrency exchange FTX, was motivated to break the law by his desire to give away as much money as possible to worthy causes.

In the conversation we go over:

- The rise and fall of FTX and some of its impacts

- What Toby hoped effective altruism would and wouldn’t become when he helped to get it off the ground

- What utilitarianism has going for it, and what’s wrong with it in Toby’s view

- The over-optimisation argument against being fanatical about any particular goal

- The moral trade argument against going all-in on any particular moral theory

- How so-called global consequentialism, which Toby happened to write his thesis on, can help explain why even utilitarianism doesn’t recommend doing radical and crazy stuff

- And a mathematical model of how personal integrity can be insanely important even though it doesn’t vary nearly as widely as, say, the neglectedness of global problems

Toby has also been visiting the AI lab DeepMind for the better part of a decade, so at the end I get his thoughts on which AI labs he thinks are acting responsibly, how he rates the behaviour of each of the main actors, and how having a young child affects his feelings about AI risk.

I then couldn’t resist getting a quick reaction from Toby to the argument we’ve heard on the show multiple times earlier in the year: that problems in infinite ethics present a fundamental and inescapable problem for any theory of ethics that aspire to be fully impartial.

And finally, we hear how it could possibly be that Toby ended up being the source of the highest quality images of the Earth from space.

All right, the email for the show if you’d like to send us feedback is always [email protected].

And now I bring you Toby Ord.

The interview begins [00:04:03]

Rob Wiblin: Today, I’m speaking with Toby Ord, a mathematician turned moral philosopher at Oxford University. His work focuses on the big-picture questions facing humanity. His early work explored the ethics of global health and global poverty, and this led him to create an international society called Giving What We Can, whose members have pledged now over $3 billion to the most effective charities that they can find.

In those early years of Giving What We Can, from 2007 through 2013, he was perhaps the prime mover in the emergence of effective altruism as an intellectual and social movement — that people understood it by that term, and viewed it as a coherent thing.

In 2021, he published the book The Precipice: Existential Risk and the Future of Humanity, which was very well received and read by policymakers around the world — ultimately being referenced extensively in UN Secretary-General António Guterres’s plan for his second term, titled Our Common Agenda. We talked about that book back when it was being conceived for episode #6: Toby Ord on why the long-term future of humanity matters more than anything else, and then again when it came out for episode #72: Toby Ord on the precipice and humanity’s potential futures.

Over the years, Toby has advised many groups, including the World Health Organization; the World Bank; the World Economic Forum; the US National Intelligence Council; and the UK Prime Minister’s Office, Cabinet Office, and Government Office for Science.

Thanks for coming back on the show, Toby.

Toby Ord: It’s wonderful to be back.

Rob Wiblin: I hope to talk about the importance of personal integrity and what key things we’ve learned about AI since The Precipice came out three years ago. But first, what are you working on at the moment and why do you think it’s important?

Toby Ord: Well, I don’t know if you’ve noticed, but quite a lot of stuff’s been going on with AI recently.

Rob Wiblin: I think we’ve noticed.

Toby Ord: Yeah. Maybe some large fraction of my time is even just keeping up with what’s going on. In the first part of this year, there’d been a lot of action on improvements in AI capabilities, where we saw Bing and then GPT-4 and a bunch of other things, the open source movement in AI really taking off. And then more recently, there’s been real developments in the policy side. The Overton window on what’s acceptable to think about AI progress and the risks that it might bring has really shifted in the last month or so.

So I’ve been doing a lot of thinking about what would be good policy proposals going forward, and how in general the landscape has shifted and how that should change our strategy.

Rob Wiblin: What sort of things would people have looked askew at you for saying a year ago, that now are very much on the table?

Toby Ord: Well, I think the big one is that AI poses an existential risk to humanity. That’s something where there’s still a bunch of debate about it. But a couple of weeks ago, there was a statement signed by the heads of all three of the AGI labs and many other people on their teams, as well as a real who’s who of scientists working on AI and many other people from other walks of life. And the statement was just very short. It was just saying that we believe that AI poses a risk of human extinction and should be a global priority. And so that was a very clear statement.

And actually, not many people noticed, but a couple of days later, The Elders — this group of former heads of state, and leaders of the UN and the World Health Organization, and other things — they put out their own statement, which said that they thought that AI posed an existential threat to humanity. And that was signed by such non-tech-bros as Mary Robinson, former president of Ireland, former president of Oxfam; Ban Ki-moon, former Secretary-General of the United Nations; Gro Harlem Brundtland of the WHO. And then after that, we had the current Secretary-General, who didn’t exactly say it was an existential risk; he said people are suggesting that it is an existential threat to humanity and we need to take that seriously — which is probably about as close as we’ll hear from him on this topic.

So things have really shifted. And then we’ve even had the prime minister here in the UK, Rishi Sunak, meeting with AI leaders and also proposing a summit to talk about national and international governance of AI because of these risks that it could produce.

Rob Wiblin: Has the response across the board exceeded your expectations, or would you wish it had gone even better?

Toby Ord: Well, I mean, it’s hard to get more groups of senior people — both within AI, the scientists and the executives, and then also in terms of prominent world figures — to actually make explicit statements. So that definitely has exceeded expectations. And it’s moved very quickly.

That said, partly because it’s moved so quickly, I think it’s left a bunch of people behind. There are people who are saying, “Wait, what?” The conversation is a bit chaotic. There’s especially a strand of people saying, “Well, they would say that, wouldn’t they?” which particularly puzzles me. I would think that in general, executives and CEOs of organisations wouldn’t say that their product could kill you and your family and that we need to be careful about that and regulate ourselves. And even if it was some kind of seven-dimensional chess, it wouldn’t be at the same time that all of these other world leaders and scientists make the same statement about their potential dangers.

I think that we would have loved it if, when the first evidence started coming out that fossil fuels could cause serious environmental problems or that tobacco could cause serious health problems, if the leaders of those companies said, “OK, this is an issue, and we’re going to need to regulate and deal with it and be regulated.” That’s exactly what we hope that these people would say. So I think that’s a much more sensible take.

Rob Wiblin: Yes. Overall, I’ve been impressed with the number of people who have very quickly cottoned on to what a serious issue this is, and how many different material risks there are that we don’t yet have a good grasp of, and that we haven’t yet taken any measures to mitigate. But there definitely has been a lot of very odd reactions. I think that’s one that definitely stands out as completely baffling: people saying, “Well, of course Sam Altman would say that his product might kill everyone on Earth, because that’s a good way to build hype and raise more money.” It’s hard for me to understand what is going on inside people’s heads that would just say something so batty from my point of view.

Toby Ord: Yeah, I think that this will be a brief window where that argument seems sensible to some people.

The fall of FTX [00:10:59]

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. Well, we’re going to come back to AI later in the conversation. But first off, I wanted to talk about effective altruism as a social movement, and some insights from moral philosophy that might be particularly useful for people who are trying to do a lot of good with their career.

So, years ago, you were really involved in the emergence of effective altruism as both a stream of intellectual thought and as a group of people trying to take action on those ideas. I guess you’ve taken more of a backseat on it in recent years, in order to free up time for other priorities like working on artificial intelligence issues.

But you were asked to give the opening address to the main conference of the effective altruism movement called Effective Altruism Global when it was held in the Bay Area back in February, in order to address the extraordinary ups and downs that that group had experienced over the course of 2022. I really loved that talk. I wanted to go through quite a lot of the things that you said in it here today, and maybe dig into a few of them. Basically, you used the events of 2022 to go through a series of important lessons from the philosophy of doing good that actually transcend any specific case and are useful to keep in mind at all times, which were made particularly salient by things that had happened.

But we should do a little bit to set the scene. Can you give a short summary of the ups and downs that you were reacting to in your talk?

Toby Ord: Yeah, I was especially referring to a series of events connected to FTX, this company set up by Sam Bankman-Fried, and his attempt using this vehicle to make a lot of money in order to give it away and thereby do a lot of good — something that he certainly stated that he saw as part of effective altruism and its mission.

Even in the first half of the year though, before all of these scandals broke out, it was a wild ride. The amount of funding going into effective altruism and the types of projects that we care about was extreme. There was an attempt through the associated FTX Future Fund to really scale up the giving very quickly. And I understand the motivation behind that: ultimately, if you do these things slowly, then you’re doing less good than you could have perhaps during a really critical period in humanity’s development. And so getting to scale quickly could really matter.

But it was also a pretty white-knuckle ride, where just every week or month, amounts of money that you hadn’t seen or heard of before were being awarded for the best blog post on something. And all of these prizes and rewards, they caused a number of issues. I mean, they created distortions where I could have probably made more money by switching to becoming a blogger instead of a philosopher in order to try to scoop up some of these awards. I didn’t do that, but some people might have actually moved towards whichever particular area had announced a prize first.

And then there was also this strange problem, where in the early days of effective altruism there was no money in it. If you could get a job in an EA organisation, you would earn substantially less than market rates. And so you knew that the people who are working on these issues with you weren’t in it for the money, because there wasn’t any. Whereas all of a sudden there was so much money that it was starting to become hard to know if you met new people in the area, what had brought them in, and did they have the same moral motivations or not. So there were a bunch of these problems.

Another one was politics: all of a sudden, there was a whole lot of money being invested in politics and associated with effective altruism. I thought that was a terrible idea. We’d tried so hard with effective altruism to not associate it with party politics, because it should be the kind of idea that everyone can get behind. No side has a monopoly on the idea of using your career or your money to help others. And then all of a sudden there was a risk that it would be perceived as politically biassed from this.

So that upwards trajectory was really hard to deal with, I think, for a lot of us.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah, it was a very strange time. I guess I hadn’t really been paying almost any attention to FTX or Sam Bankman-Fried until quite late in 2021, when it suddenly burst onto the scene. I guess the valuation must have gone up enormously. And then there was also a decision by some people to try to start deploying a whole bunch of money really very rapidly. So there was a big increase in the amount of funding that philanthropists had effectively earmarked to work on particular longtermist projects, or particular interventions associated with effective altruism. That meant that it seemed like the amount of money that people were trying to deploy, maybe per month, had tripled or something like that. So it was a “vertiginous rise,” as you say in your talk, and it had this very freewheeling sense to it from January through November of 2022.

Yeah. Do you want to talk a little bit about the fall as well, for people who haven’t been paying attention?

Toby Ord: Yeah, I was going to say it really put it into the news, although even before the fall, that’s another one of the aspects: the rise was FTX being everywhere in the news. And then also people hearing about effective altruism through this FTX idea: one particular person’s attempt at earning to give, and a very unscrupulous attempt being the thing. And even before the fall, it was associated with crypto, which was an area that while some people, I’m sure, have entirely noble intentions, there were many scammers. And so it was a problematic area to be intimately associated with.

Then we started to hear news that FTX had gone bankrupt. And then as more information came out, it seemed that it wasn’t just that it had fallen to 10% of its valuation — it had gone to negative. And it was a bit mysterious as to how this was supposed to have happened with a crypto exchange. It shouldn’t really be able to lose all of its money like this.

And then as more information came out, it seemed — and it currently does still seem — that there was a problem involving these two branches of the company. I guess they’re technically two separate companies, Alameda and FTX, both started by Sam Bankman-Fried — where Alameda was a trading company, trading on crypto, and FTX was an exchange. And they had a kind of special secret relationship together, where FTX gave Alameda better access to the exchange than it gave to the other people on it. But worse than that: in some complex, messy way, effectively the trades that Alameda was making appear to have been backed, as security, by the investments that all of the people who were using FTX had deposited. So even though these deposits were technically meant to be completely safe, because they were meant to be securely encrypted, ultimately it looks like customers will lose a very large fraction of their deposits.

Although that’s not fully known yet. In fact, there’s a lot of features of this that still aren’t fully known, including details of what exactly happened and also details of the actual motivations. Was it just Sam or did other people know about this? I’m sure much more of this will come out. There’s still going to be a major court case on this, and a number of books investigating it and so on, but it’s a massive financial scandal and catastrophe for the depositors who had invested in this.

So that is a pretty shocking thing, actually, to be reading about in the news, even if it wasn’t connected to a social movement that you helped to found — where it’s rather more shocking and devastating, really, that someone would do these things which appear to have been both illegal and immoral. And even if somehow it had worked, and their raiding the funds of the depositors helped them pay for one more trade which managed to get them out of the red and save the company, it still would have been illegal, and I think immoral, to do this.

But because it also, on top of that, it failed, it also caused vast amounts of damage to the depositors, and then ultimately a whole lot of collateral damage in other areas — including the idea of effective altruism, and also EAs: people who try to take these ideas seriously in their life. All of a sudden, people were concerned about them, even though they had nothing to do with this case in most cases. And then all of the causes that these people were devoting their lives to try to help with, all of a sudden lost out on money that was earmarked for them and so forth.

So massive amounts of destruction, both to the general public and also to this movement that aimed at trying to actually just do good in the world.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah, I interviewed Sam Bankman-Fried, the CEO of FTX, back in early 2022, and I also put out some comments about the collapse of FTX in late November last year. So I expect quite a few subscribers to the show will at least have a passing knowledge of what went on. For people who are interested to get an update on what has been learned since then, if anything, we’ll stick up a link to the Wikipedia entry on the collapse of FTX so people can do a little bit of digging, I guess.

This interview isn’t about trying to piece together all of the facts of that case, because we have no particular expertise, and I’m sure other people will do a much better job. But back in your talk in February at Effective Altruism Global, you said that we don’t really know what fundamentally motivated Sam and some of his colleagues to do what they did; although we don’t know the specifics, we know it was probably illegal and certainly immoral actions were taken. That’s one reason why today we’re going to try to learn lessons that aren’t specific to any particular claims about precisely what went wrong in the FTX case.

But do you think it’s still the case that today, when we’re recording in June, we don’t really know the motives? Or I guess what psychologically was going on that caused people to take these actions?

Toby Ord: No, I certainly don’t know, and I think very few people actually do. But I can speculate a little bit.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. What are some of the options?

Toby Ord: Yeah, I mean, I suppose I should have added the word “allegedly” to every sentence I said before.

Here are some things that we do know: Sam, even before he’d ever heard of effective altruism, had been brought up thinking about the moral philosophy of utilitarianism by his parents, and was very dedicated to this. We can get into a bit more about exactly what utilitarianism is later, but it’s a moral philosophy that certainly has some similarities with EA. And so if he’d never heard of EA, he may well have just still followed this view. And so to the extent to which part of the concern is that he took maybe unnecessarily risky actions, or that he treated people merely as a means, or that he was prepared to break the law if it meant that he could achieve the greater good — all of these kinds of things that people think might be connected to EA — he was already committed to a theory that actually held stronger versions of those things than effective altruism does.

And there’s also concerns of connections to longtermism. And I think there is actually an even weaker case, really, that it’s very connected to longtermism. Ultimately, Sam was already very concerned about factory farming of animals and the horrible suffering and injustice involved in that. And that’s already such a big area that could take so much funding trying to actually remedy those problems that he already had reason to take big risks, and to try to be almost insatiable for money in order to try to fix those problems.

So I think that doesn’t mean that EA is off the hook or something, that it had no connection to this. One of them is that the EA community was a supportive community for someone who had non-standard views about doing good in the world. So maybe if everyone he’d talked to had just had a kind of blank stare and thought he was crazy, then maybe he actually wouldn’t have gone through with these things. Whereas if there was a community that was more receptive and thought, “If you can make 10 times as much money, maybe that’s 10 times as helpful and a really big deal” that he then saw some support.

And then there’s also the idea that he traded on this good reputation being vouched for by people in this community or something like that. I think that there’s something to that as well. That’s an aspect where I think EAs had been kind of sucked in on this. At least to the extent to which it was premeditated, or that he always had this idea he might do these things. If he was just trying to walk the right path right up until the end, and then did bad stuff, then maybe the sucked-in story doesn’t make sense either.

But I do feel that I always felt a little bit uneasy about the things that I would hear with Sam Bankman-Fried. Not uneasy enough to think that he would do something like this, just to be clear. It’s more that I thought he was the kind of person who would cut corners when he needed to, quite possibly after thinking it through and so on. But a “move fast and break things” kind of person, let’s say, as opposed to a “rob lots of people of their life savings” kind of person. But even a “move fast and break things” kind of person who seems a bit cavalier about all of these things, perhaps that was enough evidence to be substantially more cautious, regardless.

Rob Wiblin: I guess one thread on this question of the motivation thinks about it from a strategic philosophy point of view, perhaps. Another angle you could take is more around personality, I suppose — where some people are just more risk-taking than others, and just might find it unacceptable, the possibility of their business going bankrupt, and would be willing to take very extreme risks in order to try to prevent that happening, by disposition.

To me, that has always seemed at least like it’s going to be a very important part of the story. Because you can imagine so many people in a similar position, who might have similar philosophical commitments about doing good, who, just because of their personalities, would never contemplate appropriating money illegally in the way that it’s alleged that Sam did, or just taking on the kinds of crazy risks that it seemed were occurring at FTX, even potentially within the law, just in terms of, like you say, the “move fast and break things” approach to business.

Also, we’ve seen similar scandals in other financial organisations before, and there it seems like the key issues were pride, shame, recklessness, perhaps ill-judged rapid decisions — rather than anything particular about the moral philosophy of the people involved.

Toby Ord: Yeah, I think that’s quite plausible. There’s evidence that there was a culture of taking stimulants there — which I think is actually quite common in hedge funds, but perhaps to a higher degree at FTX — and these can interfere with people’s normal risk attitudes, making people more risk-loving. And yeah, I think that one could explain a lot of this just with appeal to these regular emotions of pride and shame. Ultimately, he was riding high and had built a company, becoming a billionaire at a very young age and so on. And then feeling that he had so much money to be able to give to these good causes, and that a bunch of people trying to do good were looking up to him as someone who had really succeeded in earning so that they could then do a lot of good with that money, and that if he went back down to zero, then people wouldn’t be looking up to him anymore.

So maybe that’s the kind of thing that led him to think that he could try one last double or nothing on all of this. And then perhaps when it seemed like they’d actually gone into the red, that some feeling of shame of being caught at that or ending at that stage, and pride, might have meant why they didn’t just wrap it up at that point. I think especially this is for the Alameda side of things, which I think just, as far as I can understand, could have and should have been allowed to fail at that point, rather than taking additional bets and bringing FTX down with it.

So yeah, I do feel that it’s actually quite hard to pull this all apart and to see exactly what’s gone on. And I should add that with the risk-taking behaviour, it’s also not clear that even utilitarianism would endorse these kinds of risk. He seems to have been making just bad bets. Bets that it’s not just that they’re positive expected value, but with huge variance — but actually that they’re bets with negative expected value. Ultimately, effective altruism was in a situation where it had surprisingly high amounts of funding already, such that additional funding has this diminishing marginal value at helping with the causes that we care about. And so then taking big risks with the entire future of that movement in order to try to increase that amount of money a bit more actually just seemed crazy to me.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah, that’s one reason why instinctively I’m more inclined to reach for explanations that centre on personality or perhaps error, or actually just lacking information or making judgements very quickly, perhaps when someone’s sleep deprived. Because it’s so hard to explain how the actions that were taken could be justified from the point of view of trying to do as much good as possible. It seems like unless I’m really misunderstanding how the decision looked to them, no sane person who shared the goal of trying to, say, reduce extinction [risk] would have recommended it, no external party ever would have said, “Yes, this is the step that you would take.” I mean, it’s almost funny to say it because it’s so obvious, but yeah.

Toby Ord: Anyway, yeah. I think you could well be right. And to some extent it might be galaxy-braining this whole thing to think he is very unusual in having these moral beliefs and he’s unusual in having committed this large financial fraud and so they must be connected. It could be indeed that the simplest story involves these emotions and also just error. Just he really screwed up.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah, it’ll be interesting to see what further evidence comes out about this later in the year. I think, as you say, there’s some investigative journalists — is it Michael Lewis who’s producing a book about this? I think he was actually following Sam around at the time. So he might have as good a shot as any at piecing together what on Earth was going on inside people’s heads.

The history of effective altruism [00:30:54]

Rob Wiblin: OK, let’s wind back a bit now, setting aside 2022, and turn back to the period around 2008, when you were really instrumental in getting effective altruism off the ground. How did you find yourself helping to make EA into a thing?

Toby Ord: I guess I’ve always had a lot of empathy for people who are in worse situations than myself. I’ve had a fairly privileged upbringing in a middle-class family in Australia, but I don’t think any of that is unusual. I don’t think I had unusually high empathy for others or something. Maybe a somewhat unusual desire to just be a good person, but again, not totally out of the ordinary.

And ultimately, I think that where things started looking a bit different and more distinctively EA was after I’d left Australia and come to Oxford to study. And one of the essays that we were made to write for my master’s degree was this question of: Ought we to forgo a luxury whenever we can thereby enable someone’s life to be saved? And this was, at first thought, “Yes, obviously.” And then the gears start to turn and then you think, “Oh, hang on…” If that were true, then maybe you could never have a luxury — because each luxury, if you think about how much it might cost to save someone’s life in poor countries, maybe one would keep having to exchange all of these luxuries for saving more lives.

And I realised it was connected to Peter Singer’s famous “Famine, affluence and morality” essay, where he has this idea of the drowning child in the shallow pond and the analogy to international aid. So that all connected with me. And I got to read or reread these famous papers and spend a couple of weeks thinking a lot about that.

Rob Wiblin: Is this when you were doing a PhD in moral philosophy?

Toby Ord: I was doing this inappropriately named BPhil degree, the Bachelor of Philosophy, which is Oxford’s Master’s in Philosophy. And yeah, it made me think about these things again, and really come face to face with it, actually. And I was impressed by Peter Singer, by the fact that he came face to face with these things too, and that while he didn’t quite live up to exactly the standard that he recommends in the piece — where he says you should give everything above a certain minimum bar of income — he was giving a substantial fraction of his income. And he was doing this because of the moral philosophy that he was advocating, and that he had discovered by thinking deeply about it.

And this made me realise that it really was possible, that this wasn’t just a game that academics were playing about, “What obligations do we have? I can prove this obligation. That sounds super strong, that’s really impressive as a paper.” But instead, we might actually have these obligations that we’re discovering, and that this is meaningful and should actually motivate us. And so I found that to be actually quite inspiring.

Rob Wiblin: So that’s the moral philosophy side. But as I understand it, I think a pivotal issue was also starting to engage with the empirical evidence out there about what sort of impacts can we have on the world? Because all of this is good in theory, but if you actually can’t help people in a really big way, then maybe we don’t have these obligations. But this motivated you to look into that, right?

Toby Ord: Yeah, so I’d been keeping track of these things for a while — you know, when you get told, “For only 20 cents, you can save a child’s life” or something like that in some advertising copy. And I knew enough to know that those ones weren’t true. My wife actually helped me out a bit with this. She was a medical student, now a doctor, and she knew that the 20 cents in that case is usually the cost of the vaccine or something: the cost of the actual liquid that goes into the syringe. But then you also have to pay for the syringes. You have to pay for the health workers who get out to the remote villages in order to administer the vaccines.

And then bigger than all of that, you have to deal with the fact that many people won’t get the illness at all, and also that many of the people who get the illness wouldn’t die. And so you need this number called the number needed to treat, where that tells you how many people do you need to vaccinate in order to prevent the suffering from that disease, as an example.

So I knew that some of these numbers didn’t work, but there are other numbers that seem to work and to make sense about very cheap costs for preventing blindness, for example. And so I had noticed that there seemed to be something like a factor of 10,000 between how much we could achieve for ourselves with our money [and others]. And when I say “ourselves,” I’m speaking of people from this kind of privileged background: not so much as to where you fall in the income spectrum in your own country, but particularly people from, say, the UK or Australia or the US, where even the median person, the middle person in the income distribution in those countries, are among the top percent or two in the world income distribution.

I was thinking deeply about these things and then I actually was introduced to Jason Matheny, who had been an architecture student, who had found a book called Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries, DCP, in his library at university, and it changed his life. And he dropped out of his course and actually went on to help write the second edition of that book.

And that book was all about how cost effective it can be to help people in poor countries — so actually trying to do the science on this and work out, really, how much does it cost to save a life? Or as they more commonly did it, in something like a quality-adjusted life year: so it’s important that we extend people’s lives by a larger amount, not just that they die the next month or something, and also that that extension is in as high a quality of health as possible. And also that there are things that don’t involve saving a life, such as curing blindness, which take the years in someone’s life and make them better.

And so by having this idea of a quality-adjusted life year, the universe of different ways of helping people with their health that you can compare is much larger. So it’s not just like, what’s the most effective group for doing this particular health issue? — say, the most effective group for avoiding HIV — but instead it can be for helping people with health, full stop.

So he showed me this book that he’d helped to write, DCP2, and it blew me away. And coming from a maths background, I was delighted to get the dataset of all of these 108 different ways that they had of improving people’s health. And I could see this actual distribution of how much good these different ways could do per dollar. I found that it was just this huge variation, just really massive. The middle interventions, the median, were at around $300 to give someone a year of healthy life. And that’s amazing. If you think about your own life, if you were going to lose a year of life unless you paid $300, I think for most people listening, it would be a no brainer. Even if it were the case that it was up to 100 times as much as that — $30,000 per year of life — I think a lot of people would pay that. And one way to look at that is they’d prefer to keep $30,000 after tax and gain an extra year of life for every year that they do that, compared to having a salary of $60,000. And so it was like, wow, these middle interventions are about 100 times more effective than we’d be willing to pay for health over here.

But then there were other things that were 10 times as effective as that, and then there were some that were even 10 times as effective as that. And the whole span ranged from things which are about as effective as we’d pay for in the UK through to things which are about 10,000 times more effective. And some of that variation could be explained by error in the methods; maybe some of it’s a bit exaggerated at the ends. But I could also work out that that couldn’t explain the whole thing, because there are examples — the famous example is the eradication of smallpox — which were actually more effective than anything that had been studied in this group. So it’s not that these numbers were unbelievable: even more amazing things had happened. So that was a real breakthrough for me in terms of understanding this.

The pros and cons of utilitarianism [00:39:58]

Rob Wiblin: I think originally, back in those early days, you thought of the intellectual project that you were a part of as being positive ethics, if I recall. Can you explain why you called it that?

Toby Ord: Yeah, this links back to utilitarianism. So I’d done a lot of study of utilitarianism — and actually my BPhil thesis, and ultimately my doctoral thesis as well, were about consequentialism, which is connected.

So utilitarianism is a theory that ultimately says two different things. The first thing it says is that there’s only one thing that matters, morally speaking, which is that the outcomes are as good as possible. And that principle we call “consequentialism”: the idea is that it doesn’t matter what motives you had or things like that, if you can create better outcomes, that’s what matters.

And then the second part is the idea that what makes an outcome good is purely a matter of the total amount of happiness in that outcome. And “happiness” here is understood usually quite broadly, where it means something like positive experience, even if we wouldn’t normally call that experience happiness, and you can subtract off the negative experience or suffering. So it says that what ultimately matters is the total of positive experience in the world. And that’s an idea that’s actually quite broad. You might think that there’s a bunch of things that it doesn’t capture, but when you actually look at those things, many of them do end up producing more positive experience in the world, the things we value.

The utilitarians are a group who think that actually this captures many of our moral intuitions, and that we can ground out the other things we care about in the increased happiness that they produce. So for example, things like equality and freedom tend to lead to more happiness as well.

So that’s utilitarianism. And one thing that was quite special about it is that it says that the positive matters just as much as the negative. So for example, we normally think of ethics, in common sense, in terms of these kinds of “thou shalt not” lists of prohibitions, things you shouldn’t do — you shouldn’t kill, you shouldn’t steal, shouldn’t cheat, shouldn’t lie — rather than what should you do, kind of more positive duties. And the utilitarians, because they had this symmetry between the positive and the negative, they could notice that if you save 10 lives or if you don’t save 10 lives, that’s a really big deal. In fact, according to the utilitarian, maybe that’s equivalent to killing 10 people if you don’t save 10 lives. So it’s huge.

Effectively, these facts about charity and how much we can help, the reason they’re so amazing is if you’re coming from a country that is one of the richest in the world, then it ultimately shouldn’t be that surprising that the very richest people on a global level can do so much with their money to help others.

I didn’t want to say that the utilitarians are right about this and that it’s just as important. Maybe there are also things that matter beyond good outcomes. Maybe there are certain kinds of actions you should never take, such as killing someone, no matter how good the consequences are. But if you don’t have to do any of those things — you don’t have to kill, cheat, lie, steal in order to donate money to charity — and in doing so, you could save, say, one or 10 or 100 lives during the course of your own career, then what I wanted to say was that’s a really big deal. And the utilitarians saw that, but I thought that you don’t have to be committed to all of this other stuff that they say in order to see it too. In fact, everyone should kind of agree.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. We’ve described one way that utilitarianism is a bit appealing, or at least it’s alert to an issue that maybe other streams of thought in moral philosophy haven’t had much to say about, which is: not just avoiding doing the wrong thing, but also what ways could you make the world better? What are some of the ways that utilitarianism is a combination of unintuitive and unappealing, perhaps?

Toby Ord: I think that there are two types of ways. I think there’s actually a nice characterisation that while utilitarians only care about producing good outcomes — and “the gooder the better” in terms of this — there are two kinds of limits that we normally have in our commonsense conceptions of morality, which utilitarianism doesn’t have.

The most famous one is that there are normally these limitations — we call them “constraints” — on our actions: that there are certain things that you just shouldn’t do no matter how much better you could make the outcome. And actually, people are somewhat unsure about that in extreme cases: if there is some very extreme case, where perhaps through killing someone, you could save your whole city from being killed by a terrorist or something like that. So there maybe are some cases, but generally there’s this idea of a constraint that there are things that you should never or almost never do in order to make the outcome better.

And utilitarians don’t necessarily agree with that. That said, a thoroughgoing utilitarian would notice that there probably are some pretty bad repercussions involved with breaking those rules, which would include reputational effects and a lot of other more subtle flow-on harms from these things. So whenever they’re trying to be really careful, they normally say, “Actually, we wouldn’t recommend breaking any of these rules either, but we think that’s because of these more subtle flow-on consequences and reputational effects.”

Rob Wiblin: Rather than because it’s wrong in itself.

Toby Ord: Yeah, that’s right. But you basically never see them in moral philosophy saying, “Yeah, you should do those things.” That almost never happens.

Then the other type of limit, and the other area where it can give unintuitive answers — maybe that first case actually does give fairly intuitive answers, because in the end they say you shouldn’t do those things — but this other kind of limit is what we might call a freedom or a prerogative. Where usually, we think that it’s not the case that of all the possible things that you could do today, one of them is the optimal one and that you just have to do that optimal one, and anything else is wrong. So that’s what utilitarianism says.

And we tend to think that actually there’s certain areas of your life where you should have freedoms about them, even if it’s not optimal. Let’s say there’s a choice of how many children you’re going to have, let’s say between zero, one, two, and three. We might say this is something where the intuitive theory of morality says not that you have to think about the consequences of each of those numbers of children and choose on those grounds, but rather that you should be free to have any number: procreative freedom. And so, among other things, it might say that if you earn money at a job that you’re also free to spend that money on what you want. Whereas the utilitarian might say, actually no, you’ve got an obligation to use that money on wherever can help people the most. So that’s another way in which it can be unintuitive.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah, it’s maximally extreme in this dimension. Because utilitarianism, as normally construed, would say that there’s one course of action, the very best, that is absolutely mandatory — and everything else, every other deviation from that, is completely prohibited. Which is quite distinctive relative to most other moral philosophies, I think.

Toby Ord: That’s right.

Rob Wiblin: There’s a third way in which utilitarianism conflicts with most people’s intuitions, I’d say, which is just that it says that the only thing that matters is the consequences. And I guess if we’re talking about utilitarianism as one flavour of consequentialism, it says the only thing that matters, the only thing that has moral value, is wellbeing. And so other things like justice or fairness simply are not moral concepts, or at least that they’re not intrinsically valuable. I think many people find that pretty hard to swallow.

Toby Ord: Yeah. I should say that the key aspect is that “Is this intrinsically valuable?” If you actually talk to utilitarians, they often have very strong pro-equality, pro-freedom, even pro-rights stances. But they think that these things are justified in virtue of their follow-on effects on happiness — human happiness, but also happiness perhaps more broadly construed across the animal world.

So it is a bit tricky. But you’ve got examples of people like John Stuart Mill, a very famous utilitarian, arguing for political liberalism — probably the most famous proponent of political liberalism and the freedoms that entails — and also arguing very prominently for women’s rights before the law. And he thought that both things could be founded on the happiness that would be created. You’ve got Jeremy Bentham, another very famous utilitarian, arguing for legal protections for animals and better treatment of prisoners.

Rob Wiblin: In the 18th century, to be clear.

Toby Ord: In the 18th century, yeah. And also decriminalisation of homosexuality, because he thought it was a victimless crime, and so shouldn’t be a crime and so on.

One thing that you can say in general with moral philosophy is that the more extreme theories — which are, say, less in keeping with all of our current moral beliefs — are also less likely to encode the prejudices of our times. So what we say in the philosophy business is that they’ve got more “reformative power”: they’ve got more ability to actually take us somewhere new and better than where we currently are. Like if we’ve currently got moral blinkers on, and there’s some group who we’re not paying proper attention to and their plight, then a theory with reformative power might be able to help us actually make moral progress. But it comes with the risk that by having more clashes with our intuitions, we will end up perhaps doing things that are more often intuitively bad or wrong — and that they might actually be bad or wrong. So it’s a double-edged sword in this area, and one would have to be very careful when following theories like that.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. So you say in your talk that for these reasons, among others, you couldn’t embrace utilitarianism, but you nonetheless thought that there were some valuable parts of it. Basically, there are some parts of utilitarianism that are appealing and good, and other parts about which you are extremely wary. And I guess in your vision, effective altruism was meant to take the good and leave the bad, more or less. Can you explain that?

Toby Ord: Yeah, I certainly wouldn’t call myself a utilitarian, and I don’t think that I am. But I think there’s a lot to admire in it as a moral theory. And I think that a bunch of utilitarians, such as John Stuart Mill and Jeremy Bentham, had a lot of great ideas that really helped move society forwards. But in part of my studies — in fact, what I did after all of this — was to start looking at something called moral uncertainty, where you take seriously that we don’t know which of these moral theories, if any, is the right way to act.

And that in some of these cases, if you’ve got a bit of doubt about it… you know, it might tell you to do something: a classic example is if it tells the surgeon to kill one patient in order to transplant their organs into five other patients. In practice, the utilitarians tend to argue that actually the negative consequences of doing that would actually make it not worth doing. But in any event, let’s suppose there was some situation like that, where it suggested that you do it and you couldn’t see a good reason not to. If you’re wrong about utilitarianism, then you’re probably doing something really badly wrong. Or another example would be, say, killing a million people to save a million and one people. Utilitarianism might say, well, it’s just plus one. That’s just like saving a life. Whereas every other theory would say this is absolutely terrible.

The idea with moral uncertainty is that you hedge against that, and in some manner — up for debate as to how you do it — you consider a bunch of different moral theories or moral principles, and then you think about how convinced you are by each of them, and then you try to look at how they each apply to the situation at hand and work out some kind of best compromise between them. And the simplest view is just pick the theory that you’ve got the highest credence in and just do whatever it says. But most people who’ve thought about this don’t endorse that, and they think you’ve got to do something more complicated where you have to, in some ways, mix them together in the case at hand.

And so while I think that there is a lot going for utilitarianism, I think that on some of these most unintuitive cases, they’re the cases where I trust it least, and they’re also the cases where I think that the other theories that I have some confidence in would say that it’s going deeply wrong. And so I would actually just never be tempted in doing those things.

It’s interesting, actually. Before I thought about moral uncertainty, I thought, if I think utilitarianism is a pretty good theory, even if I feel like I shouldn’t do those things, my theory is telling me I have to. Something along those lines, and there’s this weird conflict. Whereas it’s actually quite a relief to have this additional humility of, well, hang on a second, I don’t know which theory is right. No one does. And so if the theory would tell you to really go out on a limb and do something that could well be terrible, actually, a more sober analysis suggests don’t do that.

The original vision for effective altruism [00:53:46]

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. As I understand it, the vision originally was that this positive ethics, which I guess eventually came to be called effective altruism, would basically take the parts of utilitarianism that were largely uncontroversial and then basically just scrap all of the parts of it that seemed dangerous or highly controversial. What was that picture?

Toby Ord: Yeah. So here I think we could isolate something like two different principles, which utilitarianism clearly sees and strongly endorses, but we’re just going to take those two principles. We’re not going to take anything else from the theory. And those principles are that doing good — say, saving a life — really matters. So from a moral point of view, a key part of living a moral life is to do things like helping others, if you really can. So that was one part, and I think that ultimately everyone can endorse that. If there was someone whose moral theory said, “I just can’t endorse that; helping others is just irrelevant,” I would look askance at them.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. And to be clear, we’re not saying it’s mandatory, merely that it would be a good thing, all else equal, if you could provide a massive welfare benefit to someone.

Toby Ord: Yes. And if it turns out that you knew that you could save 100 lives over the course of your own life and yet you just didn’t, that there would be something that’s seriously missed there. That’s the idea. Or if you did it, that might be one of the most significant aspects of your life from a moral point of view.

So that’s the first idea. And then the second idea is one of scale: to say that saving 10 lives is a 10 times bigger deal than saving one life; saving 100 is 10 times bigger still. So sometimes, when it comes to charity, the technical term that philosophers use is that it’s “supererogatory” — which means that you don’t have a duty to do it; it’s in some other realm. And things in that realm, they have a tendency to think it doesn’t really matter which one of them that you do. Whereas I’m saying, actually, it does matter a lot.

And I think you can miss that if you’re thinking about ethics from the perspective of the agent, the person who’s making the decisions. For example, if you think about the idea of the vow of poverty that mediaeval monks used to take, that was an idea about ridding yourself of these problematic material possessions and the corruption of your soul that they could produce — as opposed to an idea about helping others as much as you can, so that you need to end up in the situation of poverty yourself, a kind of Singerian case for it.

It wasn’t like that. Once you have a focus on the others that you’re helping — and maybe not all your focus should be there, but a substantial amount — then you can imagine these people who would die but for your donation. If you imagine, say, there’s 11 people, and if you do the first donation, you’ll save one of their lives, and if you do the other one, you’ll save the other 10 people instead. And you imagine looking at these people, and talking to them, and having them be able to beg you for these things, I think that it would be pretty crazy to say you should save the one in that case.

So that was a change in focus as well, and that also led to some other changes. So one of the ideas with Giving What We Can was to be a public register of people who’ve made this commitment to give. And I agree with everyone else that it’s somewhat more gauche to give and say that you’re giving than to give and not say you’re giving.

Rob Wiblin: It might be good to say a little bit more about what Giving What We Can is. So I think around this time, you were thinking, if people think an important part of moral life is benefiting others, what concretely can we build this group of people around doing? Which led you to start Giving What We Can?

Toby Ord: Yeah, exactly. So I already partly knew this, but looking at these figures for cost effectiveness made me realise just how much we could help with money. There’s lots of things one can do with one’s life, but it’s actually pretty hard to do something like save 100 lives. But in terms of our money, actually more than half the people in the UK — if they wanted to, and made it a real commitment over the rest of their life — could save 100 lives.

And that’s somewhat surprising, and it was worth dwelling on. And so I dwelled on this quite a lot and just really kept thinking about it. And one of the changes by thinking about it so much was that I came to see this less from this obligation frame that Peter Singer popularised, and instead to see it more just as I had a strong desire to save people’s lives if I could. And I think a lot of us would. When we read stories about people who took heroic actions, sometimes they took them at massive cost, and we don’t want to imagine ourselves in that position. But at other times we think, “Wow, imagine having been able to do this and to help these people.” So that’s something which is a bit of a shift of focus.

So yeah, one aspect was that shift of focus, to be thinking more in a direction of, actually, this is just something amazing that we can do. It’s morally significant and weighty, but not just as, “Oh, damn it, I’ve got to do that, then I’ll get back to playing my PlayStation” or something. But rather, no, actually, this is what it’s all about.

That was the first one. And then also just the fact that it was money that could do so much good. And what stops this being surprising is just once you realise how seriously unequal the world income distribution is: how the people that we want to be trying to help are people who have about 100 times less money than people in the richer countries, and so it’s not that surprising if money goes about 100 times further. And it turns out that the 100 times richer is already adjusting for the fact that money goes further in poor countries; if you don’t adjust for that, then you’ll see that you should expect your money to be able to do about 400 times as much good. And then it’s possible to get a bit of extra leverage on that as well, by choosing to help fund things like, say, deworming at schools — where it’s a lot more expensive to get it done just for yourself, whereas there are economies of scale when it’s done at scale.

So realising how much good we could do with giving: that’s why there was this focus that I had on starting a new organisation for people who just who want to make a personal pledge over the rest of their lives to give at least a tenth of everything that they earn each year to help the least fortunate people in the world where they could do the most good with this. And as part of that, to have this focus on effectiveness as well: once you could see that there were some ways of giving this money which wouldn’t achieve these amazing things — perhaps that would happen if you give to people in your own country — you wouldn’t have these huge benefits. So to get that focus on giving more and giving more effectively.

And because I’d seen this quantitative data on just how effective it can be, then I was able to notice that the average person could quite reasonably, instead of giving about 1% of their income over the rest of their life, give 10% — so give 10 times more — and then to give it somewhere that’s about 10 times more effective. And if they did both those things at the same time, it wouldn’t just be 20 times as good, it would be 100 times as good, because these multiply. And so I thought having this packaged together as one idea would be especially valuable.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. So that led to the formation of Giving What We Can, where people would commit to give 10% of their income to the most effective charities.

So as I understand it, in those early days, the vision was: we were going to strip away a whole lot of the baggage that utilitarianism has, and we’re going to say merely that it’s good to provide large benefits to other people if it doesn’t come at a huge cost to yourself. And it’s better to provide even larger benefits: if you can provide 10 times as much benefit to others, then that’s roughly 10 times better again.

But we’re not going to say, as utilitarianism says, that the only thing that matters is wellbeing; that there are no other moral concerns: that’s highly controversial and probably wrong, so let’s leave that by the side. We’re not going to say that you can take any actions necessarily in order to benefit other people; we’re just going to say, inasmuch as you’re not violating any of these plausible side-constraints, like violating the rights of other people, then you ought to do it. We’re just going to leave this as an open philosophical question: what sort of side-constraints do we have, and how strongly do they bind?

Toby Ord: Yeah, that’s right. And in fact, I would go even further. Rather than describing it as a stripped-down version of utilitarianism, I’d say we take these two insights that utilitarianism made clear, and that’s all we’re going to take: just these two insights. And we’re going to say: Is it reasonable for everyone to agree with those anyway? And on inspection, I think it is. They’re just things that we should have always come to believe; it just was maybe less obvious with different approaches to ethics.

And then to say, yeah, let’s build a movement around these ideas. And in doing so, we should, at least through our giving, be able to do something like 100 times or more good than we were previously able to do. And then to be excited about that, and to share the ideas about it; and share the information that scientists, economists, health researchers had developed about the places where we can do a lot of good for others.

Rob Wiblin: Was effective altruism at the time kind of construed as a theory of normative ethics, or was it more analogised to something else?

Toby Ord: So at that time, there wasn’t quite effective altruism. There was Giving What We Can. I had met Will MacAskill in 2009, in April, and then over the next seven months, we’d worked really hard together and taken a whole lot of these ideas I’d already developed around an organisation that would become Giving What We Can, and actually just making it happen. So we were doing that, and then in the years after that, the next couple of years, I was thinking academically around this more general idea — not just when it comes to giving, but when it comes to lots of moral thought about our lives, about what we just called “positive ethics.” So that was the thinking there.

And at a similar time — 2011, I think — Will and Ben Todd gave a talk about ethical career choice, applying these ideas to career choice. They worked together and founded 80,000 Hours, and ultimately brought in other people as well, and really took those ideas to their conclusions. And then once we had these two organisations — Giving What We Can, thinking about what we can do with our incomes, and 80,000 Hours, thinking about what we can do with our careers — it was even more important to have some word that referred to all of this.

As a practical matter, we needed to set up a charity within the Charity Commission in the UK. And we wanted to just do that once and set up an umbrella that both these organisations could exist under. So we ended up having a big vote on that to try to pick the name for this, and we ended up picking the “Centre for Effective Altruism.” And the idea behind that was that in naming it, we would probably also be naming this nascent movement that people were really starting to get excited about.

Rob Wiblin: Did you imagine that this would become viewed as a moral philosophy? Or was it more like environmentalism, or some other attitude or disposition or concern that people have that isn’t viewed as an actual theory of ethics?

Toby Ord: Even when I was thinking of it as an academic project under the label of positive ethics, it was still a very broad project that could encompass many different theories. In fact, I was suggesting that any moral theory worth its salt should be endorsing these kinds of ideas. In some ways you could think of that a bit similarly to the philosophical ideas behind environmentalism or feminism, where we’re saying that women really matter, that’s the distinctive idea: that they matter just as much as men, that we’re just all people. Or environmentalism, saying that these nonhuman aspects of the environment — certainly animal lives, perhaps also plant life — that this is something that also has some kind of normative weight to it.

And in both those cases, they’re not a particular moral theory or something; there’s not just one particular kind. And feminists and environmentalists also care about heaps of other things; they come to the table with other moral commitments. Maybe they’re a Christian or a Muslim or an atheist with a particular moral view — or they’ve never really thought that much about other aspects of morality, but if you push them, they’d have a bunch of ideas — and they’re just coming together because they support just enough principles to have some things in common with these other people, to fight for something that they care about.

And ultimately, that’s how I see effective altruism, whether viewed as a philosophy, like the philosophy of environmentalism, or whether viewed as a social movement.

The harm that comes from going all-in on one theory [01:07:38]

Rob Wiblin: OK, so that’s a whole lot of history about the motivation behind naming and trying to get the ball rolling on this idea of effective altruism. Let’s maybe get back to some of the broader lessons from moral philosophy that you were prompted to reflect on more by the collapse of FTX.

There’s three in the keynote that you gave at Effective Altruism Global: firstly, the harm that comes from going all-in on just one theory; then the need to assess everything, not just acts, on their consequences; and then having a model for how personal character and integrity can be really important — even if they don’t vary nearly as widely as do, say, the importance or the pressingness of causes or the effectiveness of different interventions.

Let’s do the first one first, because it was my single favourite one. It made me really light up when I was watching it, because it was one of the cases where you’re like, “I should have seen this before, but now I clearly do.” This is the issue that there are huge risks that come with trying to get 100% of what any moral theory wants without any compromises. Can you explain how that is?

Toby Ord: Yeah. Here’s a thought experiment. You’ve got three different options available to you: option A is to save one life, which is pretty good; option B is to save 99 lives; and option C is to save 100 lives. So the classical approach in utilitarianism is to look at each of those things and see which one has the best outcome — and it’s saving 100 lives. And then we say that that’s what you have to do.

But there’s also a development within consequentialism called scalar consequentialism, which says that actually, it’s a bit of a mistake to try to connect it with rightness or obligation in quite such a binary way. And in fact, I think that the earliest utilitarians, such as Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill, actually don’t speak like that. They tend not to say that only the best thing is the right or acceptable thing. You know, John Stuart Mill says that “an act is right in proportion to the goodness of the consequences it creates.”

And I think that is a better way of thinking. Modern consequentialists have really started leaning in that direction, and they call it scalar consequentialism. The idea is that how right or important these different options are is in proportion to the goodness that they create. And so the really important thing in this case is that you don’t do option A: that’s where the really big gap is. Rather than saying C is uniquely interesting and important because it’s the best, it says, actually, B is pretty similar to C: 99 lives, 100 lives. And the real gulf is between that and A. So if you were going to just compress things down to a simple thing, it wouldn’t be “do C” — it would be “don’t do A.”

Rob Wiblin: Basically it would be a mistake to think that the big difference is between saving 100 lives and saving either 99 or one. Rather, the big difference is between saving one life and 99 or 100. That feels very intuitive, I think, to most people, because it’s far closer to how we think about decisions in real life.

Toby Ord: Yeah. And there’s a key aspect there that comes from a practical point, which is that, in that stylised example, that was the only thing that mattered, and the only thing there was saving these lives. But in reality, the different options involve other kinds of effects in the world, and perhaps those effects matter. So you might have a moral theory that includes things other than happiness. And maybe in trying to absolutely maximise out on happiness, you start doing damage to some of these other things.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. So what goes wrong when you try to go from doing most of the good that you can, to trying to do the absolute maximum?

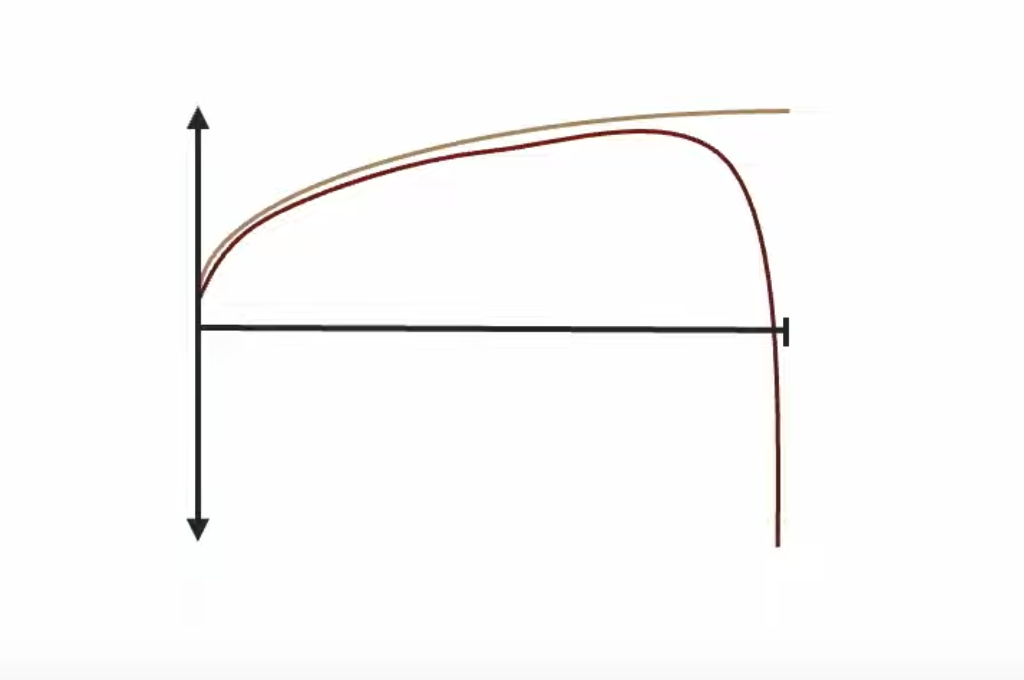

Toby Ord: Here’s how I think of it. Even on, let’s say, utilitarianism, if you try to do that, you generally get diminishing returns. So you could imagine trying to ramp up the amount of optimising that you’re doing from 0% to 100%. And as you do so, the value that you can create starts going up pretty steeply at the start, but then it starts tapering off as you’ve used up a lot of the best opportunities, and there’s fewer things that you’re actually able to bring to bear in order to help improve the situation. As you get towards the end, you’ve already used up the good opportunities.

But then it gets even worse when you consider other moral theories — if you’ve got moral uncertainty, as I think you should — and you also have some credence that maybe there are some other things that fundamentally matter apart from happiness or whatever theory that you like most says. There are these tradeoffs as you optimise for the main thing; there can be these tradeoffs to these other components that get steeper and steeper as you get further along.

So maybe, suppose as well as happiness, it also matters how much you achieve in your life or something like that. Then it may be that many of the ways that you can improve happiness, let’s say in this case, involve achievements — perhaps achievements in terms of charity, and achievements in terms of going out in the world and accomplishing stuff. But as you get further, you can start to get these tradeoffs between the two, and it can be the case for this other thing that it starts going down. If instead we were comparing happiness first and then freedom, maybe the ways that you could create the most happiness involve, when you try to crank up that optimisation right to 100%, just giving up everything else if need be. So maybe there could be massive sacrifices in terms of freedom or other things right at the end there.

And perhaps a real-world example to make that concrete is if you think about, say, trying to become a good athlete: maybe you’ve taken up running, and you want to get faster and faster times, and achieve well in that. As you start doing more running, your fitness goes up and you’re also feeling pretty good about it. You’ve got a new exciting mission in your life. You can see your times going down, and it makes you happy and excited. And so a lot of metrics are going up at the start, but then if you keep pushing it and you make running faster times the only thing you care about, and you’re willing to give up anything in order to get that faster time, then you may well get the absolute optimum. Of all the lives that you could live, if you only care about the life that has the best running time, it may be that you end up making massive sacrifices in relationships, or career, or in that case, helping people.

So you can see that it’s a generic concept. I think that the reason it comes up is that we’ve got all of these different opportunities for improving this metric that we care about, and we sort them in some kind of order from the ones that give you the biggest bang for their buck through to the ones that give you the least. And in doing so, at the end of that list, there are some ones that just give you a very marginal benefit but absolutely trash a whole lot of other metrics of your life. So if you’re only tracking that one thing, if you go all the way to those very final options, while it does make your primary metric go up, it can make these other ones that you weren’t tracking go down steeply.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah, so the basic idea is if there’s multiple different things that you care about… So we’ll talk about happiness in life versus everything else that you care about — having good relationships, achieving things, helping others, say. Early on, when you think, “How can I be happier?,” you take the low-hanging fruit: you do things that make you happier in some sensible way that don’t come at massive cost to the rest of your life. And why is it that when you go from trying to achieve 90% of the happiness that you could possibly have to 100%, it comes at this massive cost to everything else? It’s because those are the things that you were most loath to do: to just give up your job and start taking heroin all the time. That was extremely unappealing, and you wouldn’t do it unless you were absolutely only focused on happiness, because you’re giving up such an incredible amount.

Toby Ord: Exactly. And this is closely related to the problem with targets in government, where you pick a couple of things, like hospital waiting times, and you target that. And at first, the target does a pretty good job. But when you’re really just sacrificing everything else, such as quality of care, in order to get those people through the waiting room as quickly as possible, then actually you’re shooting yourself in the foot with this target.

And the same kind of issue is one of the arguments for risk from AI, if we try to include a lot of things into what the AI would want to optimise. And maybe we hope we’ve got everything that matters in there. We better be right, because if we’re not, and there’s something that mattered that we left out, or that we’ve got the balance between those things wrong, then as it completely optimises, things could move from, “The system’s working well; everything’s getting better and better” to “Things have gone catastrophically badly.”

I think Holden Karnofsky used this term “maximization is perilous.” I like that. I think that captures both what’s one of these big problems if you have an AI agent that is maximising something, and if you have a human agent — perhaps a friend or you yourself — who is just maximising one thing. Whereas if you just ease off a little bit on the maximising, then you’ve got a strategy that’s much more robust.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah, I think effective altruism is associated with this phrase “doing the most good.” And your talk made me think that maybe we should switch that to “do most of the good that you can” — because then you’re getting most of the value, because you’re above 50% of your potential. But it means that you have to give up so much less in the rest of your life, and it seems way more sustainable, much more plausible that you might be able to get above 50% of your potential and to be satisfied with that, than to try to reach 100% — which is kind of crazy.

Toby Ord: Yeah, I like it. I think we may still need a bit more work on the marketing. It certainly sounds like a very distinctive claim: “Do most of the good,” or “EA: 80/20 it in terms of doing good.” But I think it is getting at something. And I had actually always been a bit frustrated by some of these maximising-framed slogans or ways of expressing the point, because it always seemed to me that the real key thing is that we’re trying to get in the ballpark of the best outcomes, and that’s really what it’s all about. And one of the things I mentioned in the talk, actually, is “strive for excellence rather than perfection.” I think that is perhaps a way of summarising some of this. There’s good life advice on a lot of different dimensions.

But I think another subtle way that it’s true is that striving for excellence helps you think, “Maybe I shouldn’t be satisfied with how much everyone else achieves on this thing. Maybe I can just do way better.” Maybe when it comes to times for running races, you probably are pretty close to the limits. But for some other things, maybe you could actually do 10 times better than anyone before, by thinking outside the box and working out some new way to do it. And so it incentivises really taking the things you care about and trying to do amazing at them — whereas the perfection mindset feels like you’ve just got a couple of percentage points left to go, and you’re just trying to get them done. And it can lead to a “penny wise and pound foolish” type of behaviour, where you can’t see the forest for the trees. I think that the excellence approach fits the EA mindset better.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah, so one way that real life deviates from this schema — where you’re just choosing between saving one life, 99 lives, and 100 lives — is that we care about multiple different values. We care about more things than merely saving lives. The picture is more complicated. There’s also uncertainty about what effects your actions are going to have. And one reason why you might have serious reservations about a course of action is that it carries with it enormous volatility, enormous uncertainty about the effect that it’s going to have.

So I think another way that you might go wrong if you’re just absolutely maximising the expected value of something, without any compromises, is that those last few things that you do might be extremely risky. They might have positive expected value, but bring with them enormous risk of downside. So you might expect recklessness is the sort of thing that would result from being completely uncompromising in the pursuit of just one goal.

Toby Ord: Yeah, that can be especially true if the thing that you’re trying to maximise has within it a claim that you should be trying to maximise the expected value. There are different attitudes you can take to risk, and different ways that we can conceptualise what optimal behaviour looks like in a world where we’re not certain of what outcomes will result from our actions. This is studied in ethics and in decision theory and the study of rationality within philosophy. Expected value is probably the most dominant theory, which says that you should weight the outcomes by their probabilities that they occur.

But there are other approaches that involve being more risk-averse than that, which also have some credibility. And I think we should have some uncertainty around these things, and we should certainly be risk-averse about things like money that have diminishing marginal value.

Perhaps another way that one can go wrong, in fact, is: suppose you thought that money mattered a lot and was very valuable because money could be used to produce the end that you’re seeking in the world. No matter what charity it is, you could earn money and then give it. But then you’d get an extreme version of this, because ultimately, if there are diminishing returns on this money, if you’re risk neutral about money then that’s a big mistake. If there are diminishing returns on something, then that implies that you need to be risk-averse about it. And people can often forget that.

Moral trade [01:21:56]