#74 – Dr Greg Lewis on COVID-19 & catastrophic biological risks

Our lives currently revolve around the global emergency of COVID-19; you’re probably reading this while confined to your house, as the death toll from the worst pandemic since 1918 continues to rise.

The question of how to tackle COVID-19 has been foremost in the minds of many, including here at 80,000 Hours.

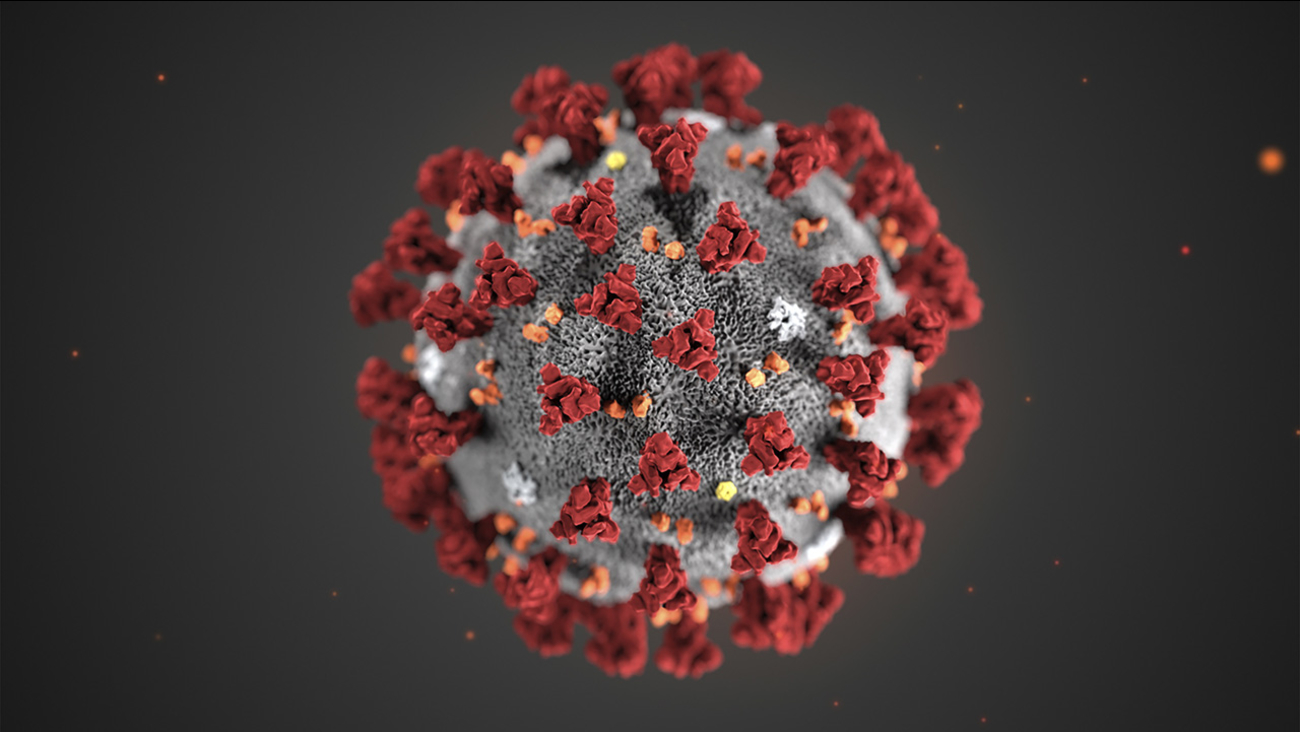

Today’s guest, Dr Gregory Lewis, acting head of the Biosecurity Research Group at Oxford University’s Future of Humanity Institute, puts the crisis in context, explaining how COVID-19 compares to other diseases, pandemics of the past, and possible worse crises in the future.

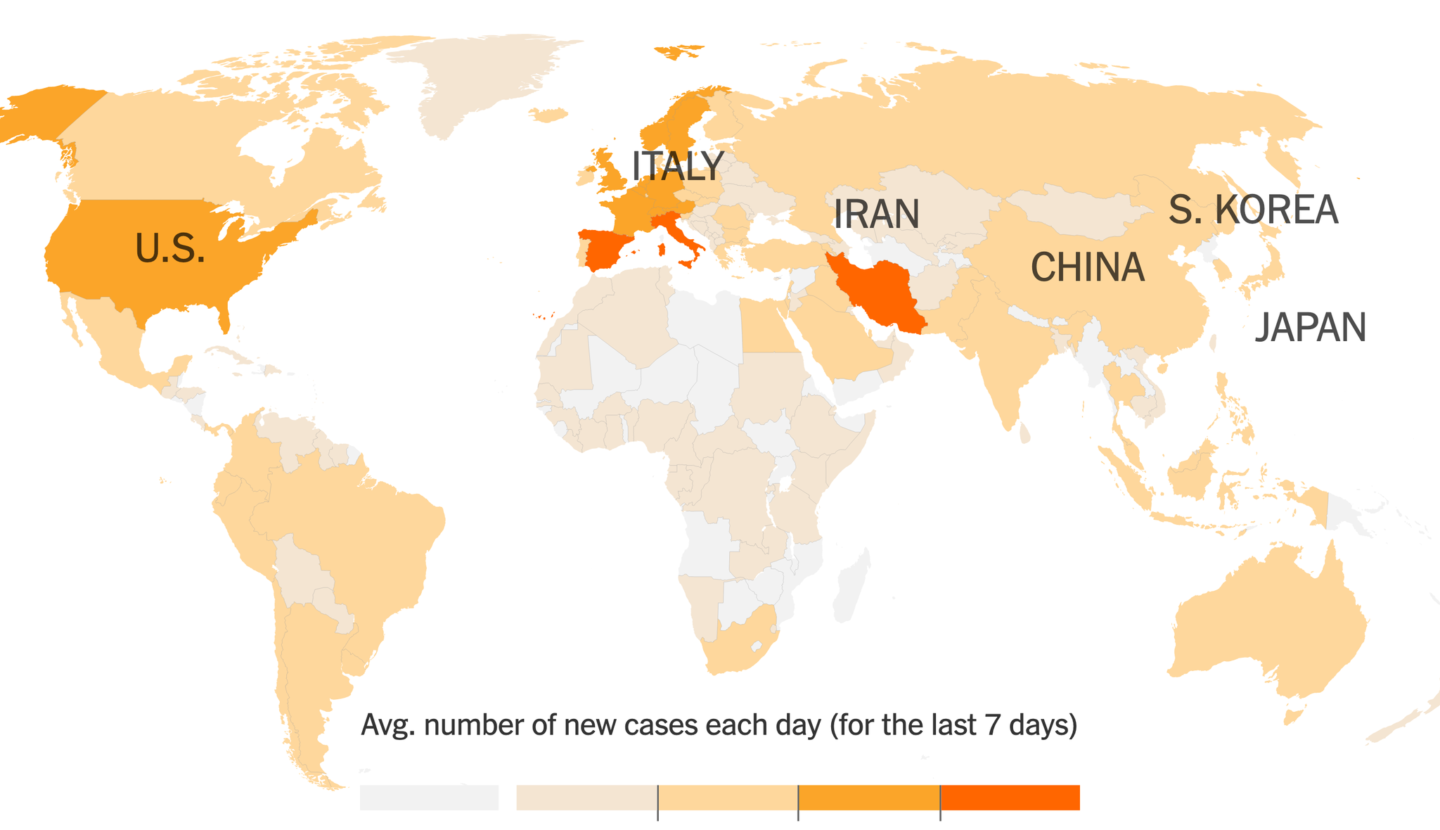

COVID-19 is a vivid reminder that we are vulnerable to biological threats and underprepared to deal with them. We have been unable to suppress the spread of COVID-19 around the world and, tragically, global deaths will at least be in the hundreds of thousands.

How would we cope with a virus that was even more contagious and even more deadly? Greg’s work focuses on these risks — of outbreaks that threaten our entire future through an unrecoverable collapse of civilisation, or even the extinction of humanity.

If such a catastrophe were to occur, Greg believes it’s more likely to be caused by accidental or deliberate misuse of biotechnology than by a pathogen developed by nature.

There are a few direct causes for concern: humans now have the ability to produce some of the most dangerous diseases in history in the lab; technological progress may enable the creation of pathogens which are nastier than anything we see in nature; and most biotechnology has yet to even be conceived, so we can’t assume all the dangers will be familiar.

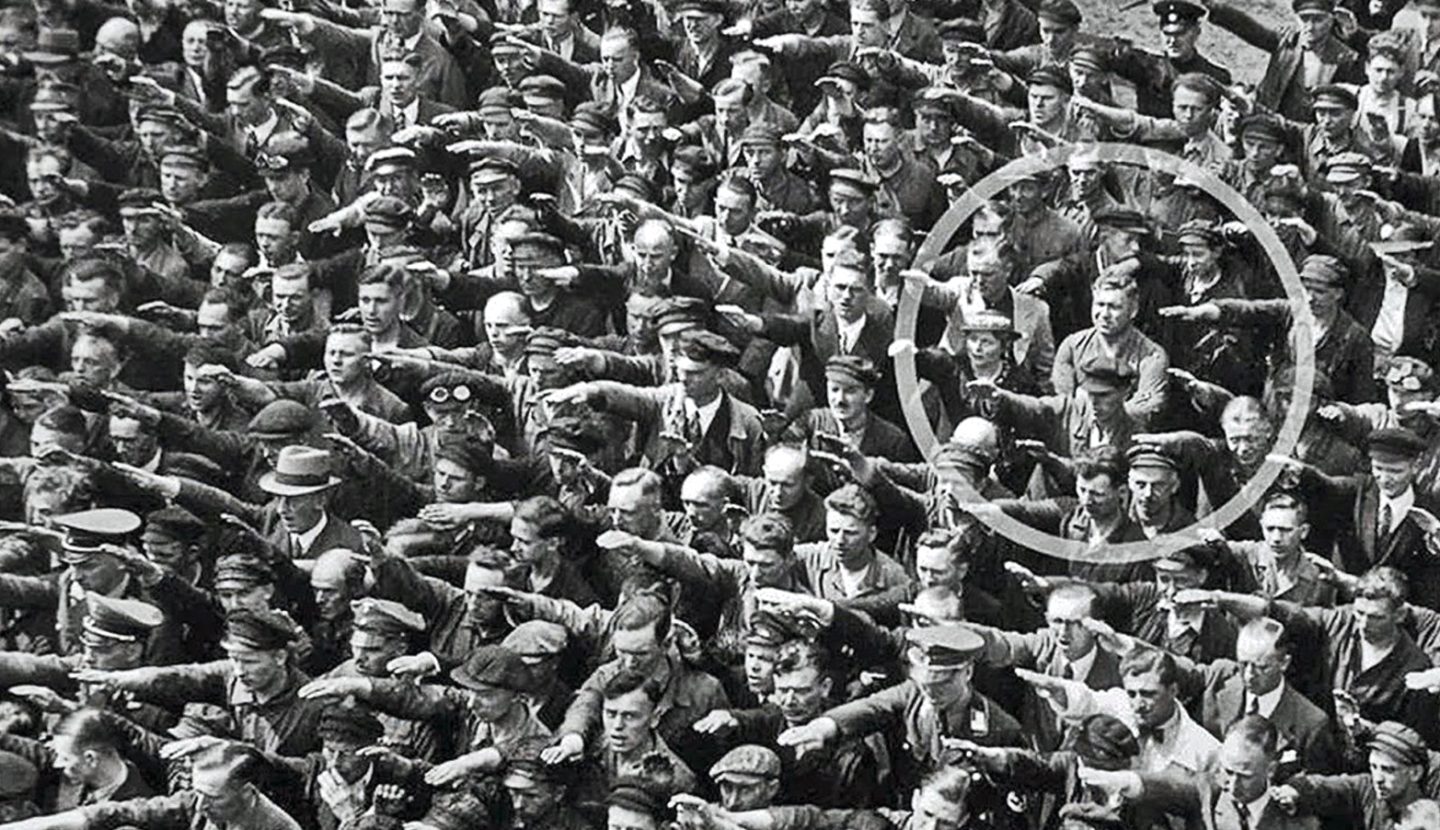

This is grim stuff, but it needn’t be paralysing. In the years following COVID-19, humanity may be inspired to better prepare for the existential risks of the next century: improving our science, updating our policy options, and enhancing our social cohesion.

COVID-19 is a tragedy of stunning proportions, and its immediate threat is undoubtedly worthy of significant resources.

But we will get through it; if a future biological catastrophe poses an existential risk, we may not get a second chance. It is therefore vital to learn every lesson we can from this pandemic, and provide our descendants with the security we wish for ourselves.

Today’s episode is the hosting debut of our Strategy Advisor, Howie Lempel.

80,000 Hours has focused on COVID-19 for the last few weeks and published over ten pieces about it, and a substantial benefit of this interview was to help inform our own views. As such, at times this episode may feel like eavesdropping on a private conversation, and it is likely to be of most interest to people primarily focused on making the long-term future go as well as possible.

In this episode, Howie and Greg cover:

- Reflections on the first few months of the pandemic

- Common confusions around COVID-19

- How COVID-19 compares to other diseases

- What types of interventions have been available to policymakers

- Arguments for and against working on global catastrophic biological risks (GCBRs)

- Why state actors would even use or develop biological weapons

- How to know if you’re a good fit to work on GCBRs

- The response of the effective altruism community, as well as 80,000 Hours in particular, to COVID-19

- And much more.

Get this episode by subscribing to our podcast on the world’s most pressing problems and how to solve them: type “80,000 Hours” into your podcasting app. Or read the transcript below.

Producer: Keiran Harris.

Audio mastering: Ben Cordell.

Transcriptions: Zakee Ulhaq.