Randomised experiment: If you’re genuinely unsure whether to quit your job or break up, then you probably should

One of my favourite studies ever is ‘Heads or Tails: The Impact of a Coin Toss on Major Life Decisions and Subsequent Happiness’ by economist Steven Levitt of ‘Freakonomics’.

Levitt collected tens of thousands of people who were deeply unsure whether to make a big change in their life. After offering some advice on how to make hard choices, those who remained truly undecided were given the chance to use a flip of a coin to settle the issue. 22,500 did so. Levitt then followed up two and six months later to ask people whether they had actually made the change, and how happy they were out of 10.

People who faced an important decision and got heads – which indicated they should quit, break up, propose, or otherwise mix things up – were 11 percentage points more likely to do so.

It’s very rare to get a convincing experiment that can help us answer as general and practical a question as ‘if you’re undecided, should you change your life?’ But this experiment can!

I wish there were much more social science like this, for example, to figure out whether or not people should explore a wider variety of different jobs during their career (for more on that one see our articles on how to find the right career for you and what job characteristics really make people happy).

The widely reported headline result was that people who made a change in their life as a result of the coin flip were 0.48 points happier out of 10, than those who maintained the status quo. If the assumptions of this so-called ‘instrumental variables’ experiment hold up, and it’s reasonable to think they mostly do, that would be the actual causal effect of making the change rather than just a correlation.

But if we actually read the paper we can learn much more than that.

This average benefit was entirely driven by people who made changes on important issues (‘Should I move’) rather than less important ones (‘Should I splurge’). People who made a change on an important question gained 2.2 points of happiness out of 10, while those who made a change on a unimportant question were no more or less happy. (Though please don’t go shaking up your life before reading some important caveats below first!)

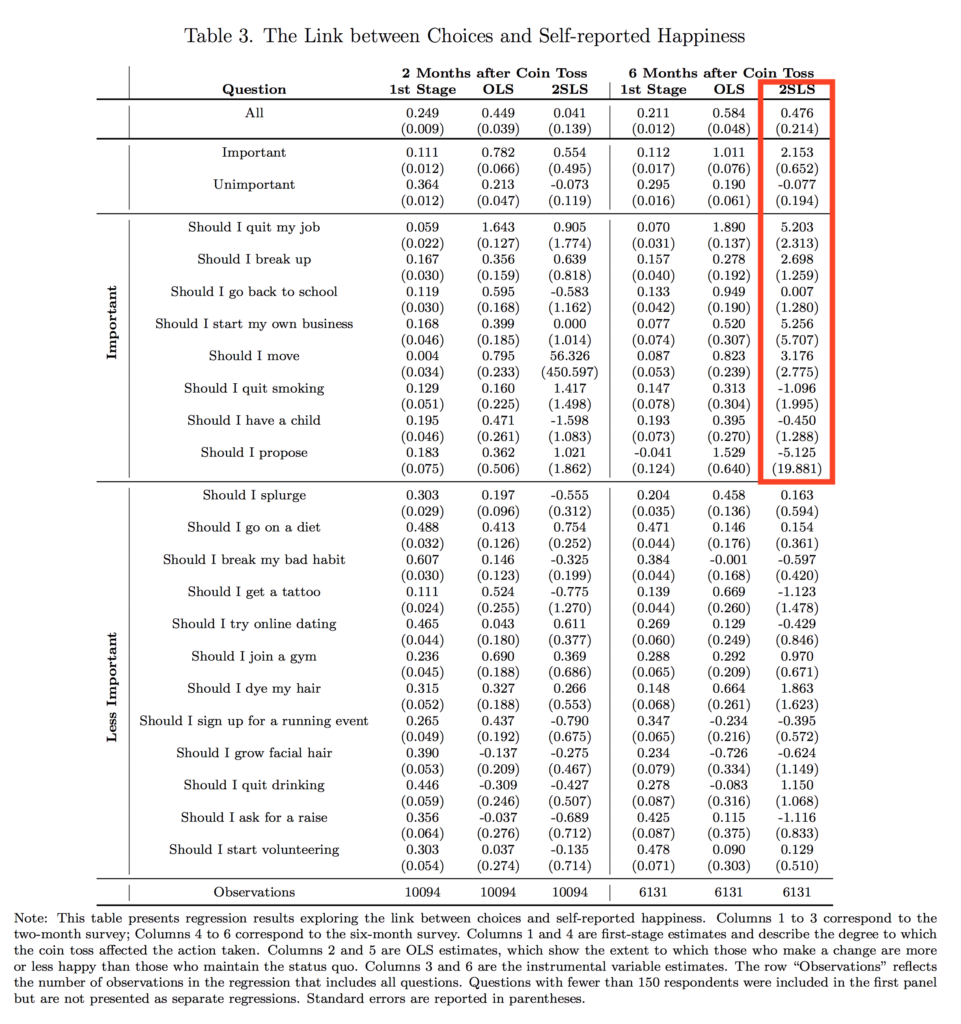

We can dig deeper and see which specific changes people particularly benefited from. Stick with me for a moment. The study says:

“The remaining rows of Table 3 present results for individual questions. These coefficients are not precisely estimated and are statistically significant in only a few instances. Job quitting and breaking up both carry very large, positive, and statistically significant coefficients at six months. Going on a diet is positive and statistically significant at two months, but has a small and insignificant impact by six months. Online dating is positive and significant at the 0.10 level at two months, but turns negative by six months. Splurging is negative and significant at the 0.10 level at two months, but has no discernible impact by six months. Attempting to break a bad habit is negative with a t-stat of 1.5 at both points in time, perhaps because breaking bad habits is so hard.”

OK, so job quitting and breaking up both have “very large, positive, and statistically significant coefficients at six months”. How big? Ludicrously, insanely big.

The causal effect of quitting a job is estimated to be a gain of 5.2 happiness points out of 10, and breaking up as a gain of 2.7 out of 10! This is the kind of welfare jump you might expect if you moved from one of the least happy countries in the world to one of the happiest, though presumably these effects would fade over time.

Both results are significant at the p=0.04 level, and fortunately I don’t think Levitt had many if any opportunities for specification mining here to artificially drive down the p value.

You can see the full results from table 3 in the paper here. I’ve put the key numbers in the red box (standard errors are in parentheses):

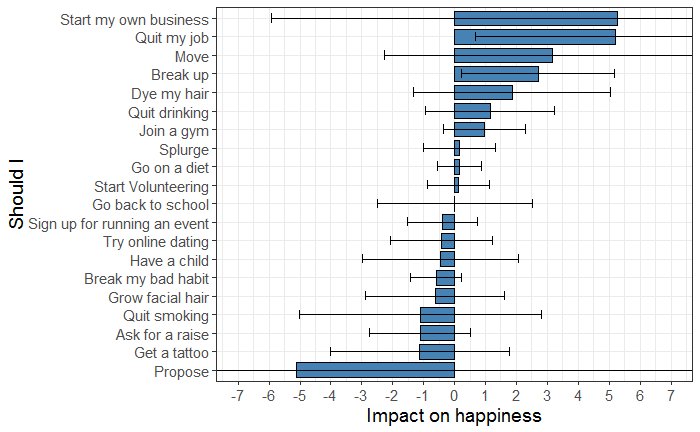

Jonatan Pallesen kindly turned this into a graph which makes it easier to see how few of these effects are statistically significant (all but two of the confidence intervals include zero):

How much can we trust the ‘quit job’ and ‘break-up’ results? On the plus side:

- This is a nearly-experimental result (using the coin toss as a sort of ‘intention to treat’).

- The specification is therefore simple and transparent.

- The results are statistically significant and pass some robustness checks.

- The sign of the result (positive) is plausible on its face, being explained by status-quo bias and risk-aversion. However, the magnitudes are unexpectedly large, and so more likely than not a chance overestimate.

- Levitt looks for indications of some forms of bias (e.g. people being inclined to overstate their happiness when they obeyed the coin flip, or those who benefitted from the change being more likely to fill out follow-up surveys) and finds little evidence for them.

- The findings are corroborated by i) survey responses from friends who also reported that the people who changed their lives really did seem happier, ii) the broader picture of people making other important changes in their life also being more likely to report higher happiness.

On the other side of the ledger:

- If these results weren’t so big I probably wouldn’t have written this post, and people might have not have shared it with you on social media, so there’s a publication bias in how they are reaching you.

- There’s a multiple-testing problem. The effects of many different kinds of life changes were tested, and I’m reporting the largest figures to you. This biases the results upwards.

- This experiment was mostly done on people who were aware of the Freakonomics Podcast, and might not generalise to other populations. However, that population is probably similar in many ways to the kinds of people who would continue reading this blog post up to this point.

- A particularly important point on the question of generalisability is that most of the benefit seemed to go to people who earned over $50,000 a year, who are presumably in a better position to weather volatility in their lives (see Table 4 in the paper).

- I’ve also noticed young people in my social circles seem very willing to change projects every 6-24 months, and I’ve wondered if this could sometimes make it hard for them to specialise, or finish anything of value. Their desire to have a large social impact may make them more flighty than the people in this experiment.

- It’s possible people who were more likely to benefit from changing were more likely to be influenced by the coin toss, which would bias the results upwards. Interestingly though the benefits seemed to be bigger for people who reported thinking they were unlikely to follow the result of the coin toss (see Table 4 again).

- Almost none of these effects were present at 2 months, which is suspicious given how large they were at 6 months. Maybe in the short run big change to your life don’t make you happier, because you have to deal with the initial challenges of e.g. finding a new job, or being single. We are left to wonder how long the gains will last, and whether they could even reverse themselves later on.

- Inasmuch as some assumptions of the experiment (e.g. people who benefitted more from changing aren’t more likely to respond to follow-up emails) don’t entirely hold, the effect size would be reduced and perhaps be less impressive.

- The experiment has nothing to say about the impact of these changes on e.g. colleagues, partners, children and so on.

On this question of reliability, Levitt says:

“All of these results are subject to the important caveats that the research subjects who chose to participate in the study are far from representative, there may be sample selection in which coin tossers complete the surveys, and responses might not be truthful. I consider a wide range of possible sources of bias and where feasible explore these biases empirically, concluding that it is likely that the first-stage estimates (i.e. the effect of the coin toss on decisions made) represent an upper bound. There is less reason to believe, however, that there are strong biases in the 2SLS estimates (i.e. the causal impact of the decision on self-reported happiness).”

On balance I think this is a good, though not decisive, piece of evidence in favour of making changes in your life, and specifically quitting your job or breaking up, when you feel genuinely very unsure about whether you should. At least for those who earn over $50,000 and whose goal is their own happiness.

Learn more

- Considering changing job? We reviewed over 60 studies about what makes for a dream job. Here’s what we found.

- Read our career guide article on how to find the job that’s the best fit for you – yes it often involves quitting several times

- Subscribe to my podcast on the world’s most pressing problems and how you can use your career to solve them

- Read the full paper

- What a well-known researcher discovered when he asked people to flip a coin on important life decisions from the Washington Post

- Would You Let a Coin Toss Decide Your Future? Full Transcript from the Freakonomics Podcast