Nuclear weapons safety and security

Jayantha Dhanapala speaking at the 2015 Review Conference for the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.

Table of Contents

In 1995, Jayantha Dhanapala chaired a pivotal conference that led to the indefinite extension of the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty.

This meant committing 185 nations to never possessing nuclear weapons.1

Dhanapala’s path started at age 17, when — after winning a competition with an essay about his hopes for a more peaceful world — he was flown from Sri Lanka to the US to meet Senator John F. Kennedy. That meeting led to a career in diplomacy (he had previously wanted to be a journalist), during which he focused on keeping the world safe from nuclear threats.

His story shows that with dedication, persistence, and a little luck, it’s possible to contribute to reducing the dangers of nuclear weapons and making the world a safer place.

In a nutshell: Nuclear weapons continue to pose an existential threat to humanity. Reducing the risk means getting nuclear countries to improve their actions and preventing proliferation to non-nuclear countries. We’d guess that the highest impact approaches here involve working in government (especially the US government), researching key questions, or working in communications to advocate for changes.

Recommended

If you are well suited to this career, it may be the best way for you to have a social impact.

Review status

Based on a medium-depth investigation

Why working to prevent nuclear conflict is high-impact

The risk of a nuclear conflict continues to haunt the world. We think that the chance of nuclear war per year is around 0.01–2% — large enough to be a substantial global concern.

If a nuclear conflict were to break out, the total consequences are hard to predict, but at the very least, tens of millions of people would be killed. It’s possible that a nuclear exchange could cause a nuclear winter, triggering crop failures and widespread food shortages that could potentially kill billions.

Whether a nuclear war could become an existential catastrophe is highly uncertain — but it remains a possibility. What’s more, we think it’s unclear whether the world after a nuclear conflict would retain what resilience we currently have to other existential risks, such as potentially catastrophic pandemics or risks from currently unknown future technology. If we’re hit with a pandemic in the middle of a nuclear winter, it might be the complete end of the human story.

As a result, we think that the risk of nuclear war is one of the world’s biggest problems. (Read more in our problem profile on nuclear war.)

Despite this, many of the people with influence in this area, including politicians and national leaders, aren’t currently paying much attention to the risks posed by nuclear weapons.

So if you can become one of the several hundred people who actually contribute to decisions that affect the risk of nuclear war, you could have an enormous positive impact with your career.

What goals should we be aiming towards?

Ultimately, decisions around the deployment and use of nuclear weapons are in the hands of the nuclear-armed states: the US, the UK, France, Russia, China, India, Pakistan, Israel, and North Korea.

Most plausible paths to reducing nuclear risk involve changing the actions of these countries and their allies.

So, which actions would be most beneficial to pursue?

Note, we’re focusing on the US (and NATO countries) here, because those are the countries most of our readers are well-placed to work in, but we’d expect many of these policies to be useful across the world. (We’ve written elsewhere about working on policy in an emerging power.)

Overall, after talking to experts in the area, we think there’s substantial value in attempting to:

- Reduce the risk of accident or miscalculation. A significant portion of nuclear risk comes from accidental use of nuclear weapons — especially during a crisis or a period of heightened tensions. There have been several close calls over the past 80 years. These risks could be mitigated by improved technology and procedures, for example by improving the reliability of early warning systems or abandoning “launch on warning” postures.

- Prevent deployment of the most escalatory weapons. For example, in early 2023, the US decided not to develop a new nuclear-armed sea-launched cruise missile (SLCM-N). SLCM-Ns are considered destabilising because of their target and payload ambiguity, so this decision was a substantial success for risk-reduction. Similarly, there may be policies that could disincentivize Russia and China from deploying some of the destabilising weapons they are currently pursuing.

- Introduce checks and balances on the use of nuclear weapons. In the US, the President has the sole authority to launch nuclear weapons. Having this authority in the hands of just one person increases the chances that the US will launch nuclear weapons when it would not be in the interests of the world to do so. There are several proposed pieces of legislation which would limit presidential authority, as could an executive order.

- Anticipate and limit potentially dangerous technological developments. We could see new risks arising from the integration of artificial intelligence into nuclear command and control or the development and use of space-based missile defences — although we’re uncertain about whether these technologies would be good or bad on net. Identifying and then prohibiting any dangerous technologies, before they are deployed — even if that’s done unilaterally (as proposed in a recent bipartisan US senate bill) — could lower the risk of catastrophe. And it might lead to reciprocal commitments by other nuclear powers, including Russia and China.

- Achieve resilient deterrence while avoiding a new arms race. We’re seeing some countries (in particular China) increase their nuclear arsenals. Ideally, a US / NATO response to this would maintain both nuclear and non-nuclear capabilities that, when combined, make it clear to adversaries they will gain no advantage by striking first or by continuing further arms buildups.

- Promote arms control dialogue between the US, China, and Russia. Unfortunately, there is virtually no chance for extension of New START, the existing nuclear arms reduction treaty between the US and Russia which is set to expire on February 5, 2026. But similar dialogue in the future could lead to substantial breakthroughs. Also, other dialogue measures can help improve relations, especially during periods of high tension, for example: codes of conduct, hotlines, transparency measures, and information exchanges.

- Strengthen international norms and laws against nuclear possession and use. For example, nuclear states could ensure their nuclear targeting is consistent with the Law of Armed Conflict. It would also be great to end up in a situation where nuclear states recognise arms control as a crucial means to achieving their own military goals.

- Develop a better understanding of the possible pathways to inadvertent escalation, especially among senior decision makers.

What does this path involve?

The aim of this path is to improve decision-making about nuclear weapons in important parts of relevant governments and to build support for risk-reduction measures.

Broadly, we think there are four ways you could work towards this goal:

- Working in governments and international organisations. We focus most on the US government, because we expect that’s the most important government where our readers will be able to have an impact. We also discuss other governments and international institutions.

- Research — both academic and non-academic.

- Communication and advocacy.

- Building the field of nuclear risk reduction.

Our guess is that you should take the option that fits you best — people’s personal fit for these categories probably varies much more than the impact between them.

If you’re not sure which fits you best, you could start figuring that out using our article about how to find the right career for you.

Working in the US government

In 1981, two young Defense Department staffers, Franklin Miller and Gil Klinger, were tasked with reviewing the US nuclear doctrine and arms control policies. They found substantial discrepancies between the official nuclear guidance documents — which recommended some measure of constraint on nuclear targeting — and the actual nuclear war plans — which recommended destroying as many targets, with as many nuclear weapons, as quickly as possible. With the backing of Secretary of Defense Casper Weinberger, they rewrote the top-level guidance for the war plan.

Seven years later, Miller, now a Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense, conducted another review of US targeting. He discovered massive redundancies, misallocations, and overkill — and concluded that the US could halve the “required” number of strategic nuclear weapons.2

Miller’s work was probably a substantial contributing factor to the dramatic decline in the number of nuclear weapons in both the US and Russia in the 1990s.

The best places to work in the US government are probably in certain parts of Congress and the executive branch.

In general, congressional staffers have a substantial influence on US government policy, making it one of the best options for policy careers across many problem areas.

As far as we know, very few congressional staff specialise in nuclear weapons, but some focus on strategic issues and appropriations relevant to nuclear weapons.

If you were to become a senior staffer with expertise in both the legislative process and nuclear issues you could have a lot of influence in key decisions.

Being a congressional staffer also means you’ll be able to contribute to helping solve other pressing problems if the opportunity arises, and it is also a great option for career capital because of its strong backup options.

To learn more, read our career review of becoming a congressional staffer.

Within the executive branch, the most relevant places to work are probably the Department of Defense, the Department of Energy, and the State Department.

Most key policy decisions related to nuclear weapons are made in the Department of Defense. People who achieve senior roles in the Department of Defense tend to develop broad national security credentials rather than specialising early in nuclear.

Within the Department of Defense, you could specialise in deterrence policy. Right now, there is a lot of interest in new thinking on how to simultaneously prepare for Russia and China (known as “the three body problem”) and in understanding “integrated deterrence”: using conventional, nuclear, and other systems to deter adversaries.

As part of the Department of Defense, there are nuclear-focused offices in the Pentagon and at STRATCOM, although these teams tend to be more enthusiastic about the use of nuclear weapons.

About half of the budget of the Department of Energy goes to the National Nuclear Security Administration, which manages the US nuclear weapons stockpile and works on nuclear safety and nonproliferation.3 We have the impression that the NNSA sometimes has a hard time hiring — in part because it’s not the flashiest part of the government despite its importance.

Working within the Department of Energy itself probably wouldn’t be as high impact, but it could still be a good place to learn and build career capital.

The National Labs, funded by the Department of Energy, have positions in them which are influential on nuclear issues — although most people working there will ultimately be working on designing and maintaining nuclear warheads. For any of these positions you are likely to need a high-level security clearance; you can find out more about US security clearances here.

With the State Department, the way to become influential is often more about being appointed to a senior role. For example, you might develop a reputation for being the go-to person on a set of issues. When a new assistant secretary or deputy assistant secretary is looking for an advisor, you can then move into that role.

We don’t usually recommend a career in the US military to reduce risks of nuclear war. It’s rare to work on nuclear weapons or nuclear policy within the military, as the US has a strong policy of civilian control of the military, especially on nuclear policy. Also, it can take decades to climb the ranks: if you pursue a career in the Air Force or Navy, and specialise in nuclear operations, you’ll spend the first 10–20 years of your career learning how to safely and reliably operate nuclear platforms, launch missiles, and maintain these systems, with no voice in policy making.

Nuclear specialisations have traditionally been seen as a bit of a dead end in the military, which means there could be an opportunity to advance relatively quickly (on nuclear issues) if you’re particularly talented. This career path might have you working as an ICBM (intercontinental ballistic missile) missileer or on a ballistic missile submarine — but we’d expect this would still be a less useful route than working in Congress or the executive branch.

That said, if you already have military experience that can be valuable career capital for other important roles in government. This is particularly true for military personnel who have been to an elite military academy (e.g. West Point, the Naval Academy, or the Air Force Academy) or for commissioned officers at rank O-3 or above.

Other governments and international institutions

Other relevant governments include China, Russia, Pakistan, India, Israel, Iran, and NATO countries in general.

The broad career path in these governments would be similar: build up broad expertise of the government, as well as specialist knowledge in nuclear policy, and move into a position where you might be able to help make decisions that would reduce the risk of nuclear conflict.

In some of these countries there are far fewer people who work on nuclear policy than in the US. This means that even if the country as a whole has less influence over global nuclear safety than the US, the influence of any particular role may not be lower than a comparable role in the US.

You could also consider working in the United Nations — particularly if you could become an advisor to the Secretary General — but we’d guess working in a relevant national government would be higher-impact for most people unless you have a particularly good opportunity to gain experience working with or for the UN.

The International Atomic Energy Agency also has some relevant roles — although they’re mainly focused on reducing proliferation. We’d guess that reducing proliferation is less important than working on reducing the chances of nuclear weapons being launched or preventing arms build-ups in countries that already have access to nuclear weapons. Also, it can be hard to get a role at the IAEA unless you have specific technical expertise or come from a country that is not overrepresented.

Research

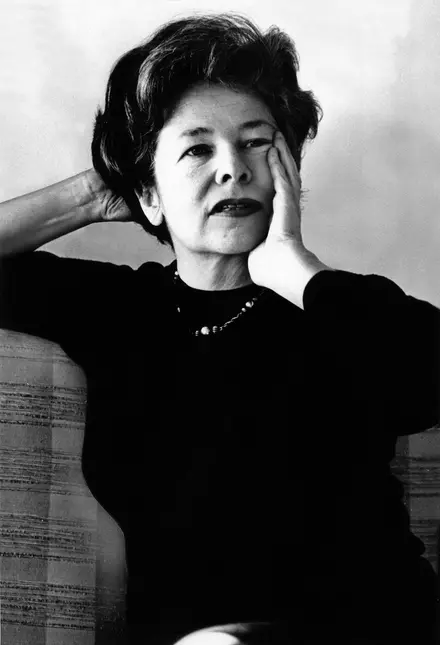

Roberta Wohlstetter, an academic historian at the RAND Corporation, left a lasting impact on defence policy with her analysis of the Pearl Harbour attack in 1962.

Her husband, Albert Wolhstetter — armed with his PhD in mathematical logic — was a nuclear strategist, and together their work formed the foundation of the nuclear strategy of the John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson administrations.4

They achieved this influence through producing important (but controversial) ideas — and the popularity of these ideas led to them becoming well-connected to the Kennedy and Johson administrations.5

Broadly, there are three main routes to having an impact through research:

- Becoming a prominent researcher and then using this to enter senior government positions (more on this above)

- Building an influential platform from which you can advocate for things which could reduce nuclear risk (more on this below)

- Trying to find answers to currently unanswered questions on nuclear risk

While the third option is what most people might think of when they consider being a “researcher,” the first two are potentially just as (if not more) impactful options for people with good personal fit.

Academic research is the most predefined route and is often the best route for building prominence and influence. But not all research happens in academic settings. Working as a researcher in think tanks can be a great way to enter government, and lots of the best research about reducing the existential risks posed by nuclear weapons happens in nonprofits or grantmaking organisations like Rethink Priorities or Founders Pledge.

What are the best topics to research?

In general, the highest impact research is likely to either help you develop a niche in which you are the go-to expert (great for developing a platform or entering government), or is unfairly neglected by the wider research community (e.g. because it’s not thought of as impressive or interesting enough and so really needs to be done by someone trying to do good).

We’re not sure what the highest impact areas are, but here are some suggestions:

- The effects of artificial intelligence on the use of nuclear weapons (read our existing views on this question)

- The interaction between nuclear risk and other risks, with a focus on the possibility of existential catastrophe (e.g. looking at biotechnology or artificial intelligence)

- What nuclear deterrence and arms control should look like in world with three near-peer nuclear competitors (the US, Russia and China all being major players)

- How we might keep nuclear war from escalating after the first bomb has gone off

For more, take a look at this list of nuclear risk research ideas.

To learn more about research careers in general, read our article about having an impact by building a research skill set.

Communication and advocacy

In 2017, 56 countries signed a treaty completely banning using, developing, testing, building, and stockpiling nuclear weapons. The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons came about in large part because of ICAN, a nonprofit international campaign to abolish nuclear weapons. ICAN organised speeches and demonstrations — and worked closely with the United Nations — and were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for their efforts once the treaty had been signed.

Ultimately, however, we’re not sure how useful this work was — no nuclear weapons states signed the treaty, and its existence doesn’t seem to have done much to change policies in any of those states or move them towards disarmament negotiations.

That said, many people believe that movement building and political advocacy is the most important lever for changing nuclear policy. After all, if there is public support for nuclear reductions, negotiations with adversaries, or reduced spending on nuclear weapons, those positions are much more likely to gain political traction. So we’re not sure, but we think that some work in this area is likely to be high-impact.

Beyond large-scale advocacy, you could consider becoming a journalist or otherwise working in the media to produce excellent coverage of nuclear weapons. Media reports can have a substantial impact — especially ones that highlight waste, fraud, abuse, or government inaction in a way that can lead to reform.

You might also consider working in communications roles in high-impact organisations focused on nuclear risk.

Working to build the field of nuclear risk reduction

During the Cold War, the US government collected physicists, economists, and social scientists together to develop nuclear policy and to prevent nuclear war. But the capacity of the field has shrunk hugely since then, especially since 9/11.

In 2022, the MacArthur Foundation, the largest philanthropic funder of nuclear risk reduction, announced it was withdrawing from the field.

This suggests that one high-impact approach to reducing nuclear risk would be to try to help reverse this decline.

This might include becoming a grantmaker, earning to give, founding new organisations, or working in leadership positions in relevant organisations.

Example people

Recommended organisations for reducing nuclear risk

Many of the best places to work won’t be specifically focused on nuclear risk reduction. These might include government organisations, media companies, political parties, and international organisations. In particular, above we discussed:

- US Congress

- US Department of Defense

- US Department of Energy (including the National Nuclear Security Administration and the National Labs

- US State Department

- United Nations

- International Atomic Energy Agency

Additionally, here are a few organisations working on reducing nuclear risk:

- The Nuclear Threat Initiative is a US nonpartisan think tank that works to prevent catastrophic attacks and accidents with nuclear, biological, radiological, chemical, and cyberweapons of mass destruction and disruption. The NTI also sponsors the William J. Perry Project, an initiative from former US Secretary of Defense William Perry to educate the public about the continuing threat of nuclear weapons. See current vacancies.

- The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace is also a US nonpartisan think tank focusing on peace and international cooperation. One of its 10 programs focuses on nuclear policy.

- Longview Philanthropy is an organisation that recommends grants focused on improving the lives of future generations. They have a nuclear security grantmaking programme that aims to grant $10 million to opportunities focused on reducing existential risks posed by nuclear weapons. See current vacancies.

- Ploughshares Fund is the largest US philanthropic foundation focused exclusively on peace and security grantmaking. It supports initiatives to reduce current nuclear arsenals and to limit the likelihood of nuclear war (and to a lesser extent, risks from chemical and biological weapons). See current vacancies.

- The Future of Life Institute works to reduce the risks from a number of areas, in particular nuclear war, pandemics, and advanced AI. See current vacancies.

- Global Catastrophic Risk Institute is an independent research institute that investigates how to minimise the risks of large-scale catastrophes, such as from nuclear war. See current vacancies.

- Alliance to Feed the Earth in Disasters (ALLFED) researches and develops alternative foods that could be quickly scaled up to feed everyone in a nuclear winter and coordinates preparedness and planning. Contact ALLFED to volunteer or apply to an open position.

Want one-on-one advice on pursuing this path?

Because this is one of our priority paths, if you think this path might be a great option for you, we’d be especially excited to advise you on next steps, one-on-one. We can help you consider your options, make connections with others working in the same field, and possibly even help you find jobs or funding opportunities.

Find a job in this path

If you think you might be a good fit for this path and you’re ready to start looking at job opportunities that are currently accepting applications, see our curated list of opportunities for this path:

Learn more about nuclear weapons safety and security

Articles:

- Our problem profile on nuclear war

- Open Philanthropy’s report on nuclear weapons policy

- Our problem profile on reducing great power war

- The case for reducing existential risks

80,000 Hours podcast episodes related to nuclear war:

- Andy Weber on rendering bioweapons obsolete and ending the new nuclear arms race

- Joan Rohlfing on how to avoid catastrophic nuclear blunders

- Jeffrey Lewis on the most common misconceptions about nuclear weapons

- Daniel Ellsberg on the creation of nuclear doomsday machines, the institutional insanity that maintains them, and a practical plan for dismantling them

- Samuel Charap on the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine and the effects of this on nuclear security (published March 2022)

- Luisa Rodriguez on why global catastrophes seem unlikely to kill us all

- David Denkenberger on using paper mills and seaweed to feed everyone in a catastrophe, ft Sahil Shah

- Lewis Dartnell on getting humanity to bounce back faster in a post-apocalyptic world

- Christian Ruhl on why we’re entering a new nuclear age — and how to reduce the risks

Thanks to Carl Robichaud and Matthew Gentzel for reviewing this article.

Read next: Learn about other high-impact careers

Want to consider more paths? See our list of the highest-impact career paths according to our research.

Notes and references

- This was achieved in a “package deal” alongside agreements from nuclear weapons states, such as an improved program of action for disarmament and reaffirming the right to peaceful uses of nuclear energy.↩

- Miller gives an account of this in chapter 23 of Uncommon Cause by General George Lee Butler.

The election of George H. W. Bush brought new management to DoD. President Bush initially chose Senator John Tower to be his Secretary of Defense, but the nomination collapsed as a result of allegations about his private life. President Bush next turned to Representative Dick Cheney of Wyoming, the House Minority Whip, who was confirmed easily… I had formed an excellent professional relationship with Mr. Cheney while he was a member of the House.

Soon after Secretary Cheney took office, the CINCSAC, General Jack Chain, came to Washington to present a brief on the SIOP [Single Integrated Operational Plan]. After the briefing, the Secretary called me to his office and asked that my team investigate General Chain’s numbers.

By the late fall of 1989 we had come to several startling findings, including that the weapon-to-target ratio in many cases far exceeded what was necessary to achieve the desired military attack goals, and that sophisticated nodal analysis had not been incorporated into attack planning, resulting in both less efficient attacks and the use of more weapons than necessary to achieve desired military objectives.

At the same time we were briefing the results of our review [of the SIOP], negotiations on the START 1 treaty were in their final phase. The draft treaty limited the U.S. and the Soviet Union to no more than 4,900 strategic missile warheads each. This gave rise to a critical question which we prompted Secretary Cheney to ask Vice Admiral Eytchison: whether, in light of the work of the review team, the U.S. could meet its deterrent requirements within the proposed limit. Eytchison, whose principal responsibility was to oversee the JSTPS on a daily basis, gave the by-the-book answer: as he was not in a position to impose requirements, he could not answer the question, which we already knew to be “yes.” The Secretary persisted: why couldn’t the Vice Director of JSTPS tell him what the war plan required? Eytchison’s answer harkened back thirty years: when President Eisenhower took steps in 1960 to ensure against the duplication inherent in the separately constructed Air Force and Navy strategic strike plans against the USSR, neither service would countenance the other being empowered to impose requirements on it. The resulting bureaucratic compromise was the Joint Strategic Target Planning Staff, whose responsibility was to allocate to a target every weapon committed to it by the Services – but not to determine the appropriate number and type of weapons through an independent analysis of what an integrated war plan, conforming to nuclear weapons employment guidance from civilian authority, would require. Thus, it was left to the Air Force and to the Navy, in their own internal budgeting processes, to decide how many strategic nuclear delivery systems to buy (e.g. 132 B-2As, 18 Trident SSBNs), each with an associated weapons load, the weapons to be fabricated by the Department of Energy and committed to the JSTPS for allocation to the war plan. Nowhere in this process was there provision for a senior civilian or military official to determine what was required based on U.S. security and nuclear deterrence objectives that had been set at the highest levels of government. The point was not lost on the Secretary and the Chairman, who had approved our proposed target base and allocation plan, and now authorized us to develop the first requirements-based SIOP in history. The resulting number was 5,888 strategic nuclear weapons, a more than 40% reduction from the 10,000 nuclear weapons the United States was entitled to deploy under the soon-to-be signed START 1 treaty.↩

- The FY 2024 President’s Budget for the Department of Energy shows the budget request by program (p.4). The total requested budget is $51.99 billion. The National Nuclear Security Administration budget is $23.85 billion, 46% of the total.↩

- According to Alain Enthoven’s commentary in Nuclear Heuristics: selected writings of Albert and Roberta Wohlstetter, “Albert Wohlstetter was the most important strategic analyst and thinker of our time. His ideas were the foundation of the overall nuclear strategy of the John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson Administrations.”

A 2018 academic roundtable reviewing The Cold War They Made: The Strategic Legacy of Roberta and Albert Wohlstetter suggests there’s now broad consensus that Roberta Wohlstetter had a substantial intellectual influence on Albert.

Finally, the reviewers are united in their praise for the book’s treatment of Roberta as not only an equal, but perhaps even the intellectual driver of the Wohlstetters’s ideas about defense policy. Academics have long appreciated Roberta’s contribution to studies of intelligence, and Jervis notes that all students of surprise attacks “take her landmark study as our starting point.” But prior studies of the Wohlstetters treat Roberta, as Eden writes (quoting Robin, 3), “as Albert’s wife, a den mother,’ “dishing out delectable soufflés,” (which Robin’s photographs do portray).[1] In contrast, Robin is an unabashed (if not uncritical) admirer of Roberta’s intellectual capabilities. He notes that Roberta had a “voracious intellectual curiosity” (29), one that ranged, as Jervis writes, across the humanities and social sciences. Perhaps most notably, he attributes Albert’s concerns about strategic vulnerability to Roberta’s thinking; as Larkin writes, “he drew much inspiration for his strategic thinking from her monograph, Pearl Harbor: A Warning, and its implication that major nuclear deployments could best ward off surprise attacks (68).[2] This raises questions, Larkin notes, about the “hidden women” of international relations theory, the extent to which prominent international relations theorists may have been influenced by female interlocutors who, unlike Roberta, may have left no written record of their own.↩

- According to a 2018 academic roundtable reviewing The Cold War They Made: The Strategic Legacy of Roberta and Albert Wohlstetter, Albert was “well connected in Washington.”↩