Why the problem you work on is the biggest driver of your impact

If you want to make a difference, which issue is best to work on — climate change, education, pandemics, or something else?

People often think that making these kinds of comparisons is near impossible. The most common advice is that you should just work on whatever issue you’re passionate about.

But we believe some global problems are far bigger and more neglected than others, and so which issues you work on will probably be the biggest driver of your impact.

Table of Contents

- 1 An introduction to comparing global problems

- 2 Some problems are bigger than others

- 3 Some problems are more neglected than others

- 4 How much do problems differ overall?

- 5 What does this spread imply?

- 6 Choosing a problem and your career: some common misunderstandings

- 7 So which issues do we think are most pressing?

- 8 Further reading on how to compare problems

- 9 Read next

An introduction to comparing global problems

We’d like to see a great many global problems get more attention, but as individuals, the best we can do is identify the biggest gaps in existing efforts and help fill them.

To find these gaps, one starting point is to look for problems that are:

- Important: if progress is made, how much social impact would result?

- Neglected: how much effort will be invested in this problem by others?

- Tractable: how easy is it to make progress per unit of resources?

In this article, we’ll argue that there are huge differences in how important and neglected different issues seem, which don’t seem to be offset by differences in tractability.

This means that by choosing a different issue, you might be able to increase how much impact you have by over 100 times.

Some problems are bigger than others

Climate change is widely considered one of the world’s biggest problems, and we think it’s even bigger than often supposed. While the most likely scenario is several degrees of warming, the uncertainty in climate models means it’s hard to rule out warming over 10°C by 2100.

What’s more, the CO2 we emit today will stay in the atmosphere for tens of thousands of years, impacting our children’s grandchildren and beyond. We think future generations matter, which makes the issue even bigger in scale.

But as we argue in our problem profile on climate change, it looks unlikely that even 13°C of warming would directly cause the extinction of humanity (though it could contribute to making other existential threats worse). As a result, we think there may be issues that are even larger still.

The philosopher Toby Ord has argued that in 1945 humanity entered a new age, which he calls ‘the Precipice.’ On July 16, 1945, humanity detonated the first atomic bomb, which would eventually make it possible — for the first time in history — that a small group of people could destroy most of the world’s cities within hours.

The annual risk of an all-out nuclear exchange is small, but it’s not zero: there is always the chance of an accident or malfunction.

The average of several expert surveys estimated the chance of a US-Russia exchange is 0.4% per year.

The probability of an all-out exchange is lower, but over our lives and the lives of our children, it could still add up to a substantial chance of a catastrophe potentially more devastating than climate change.

Besides killing most people living in urban areas, the resulting fires could lift enough ash into the air to obscure the sun and reduce global temperatures for years, leading to widespread famine through a phenomenon known as ‘nuclear winter.’

Within months, this would not only kill most people alive today, but it could also lead to a collapse of civilisation itself. We think a permanent collapse is very unlikely, but when we consider the scale of the consequences — the loss of all future generations — that risk may be the worst thing about a nuclear conflict.

But the possibility of extreme climate change and nuclear winter are just two examples of a broader trend.

Technology has given this generation unprecedented power to shape history. The consequences of the decisions we make today about nuclear weapons, genetic engineering, artificial intelligence, space settlement, and other emerging technologies could ripple forward for thousands of years, with either enormously positive or enormously negative consequences.

So: some problems are much bigger than others.

Some problems are more neglected than others

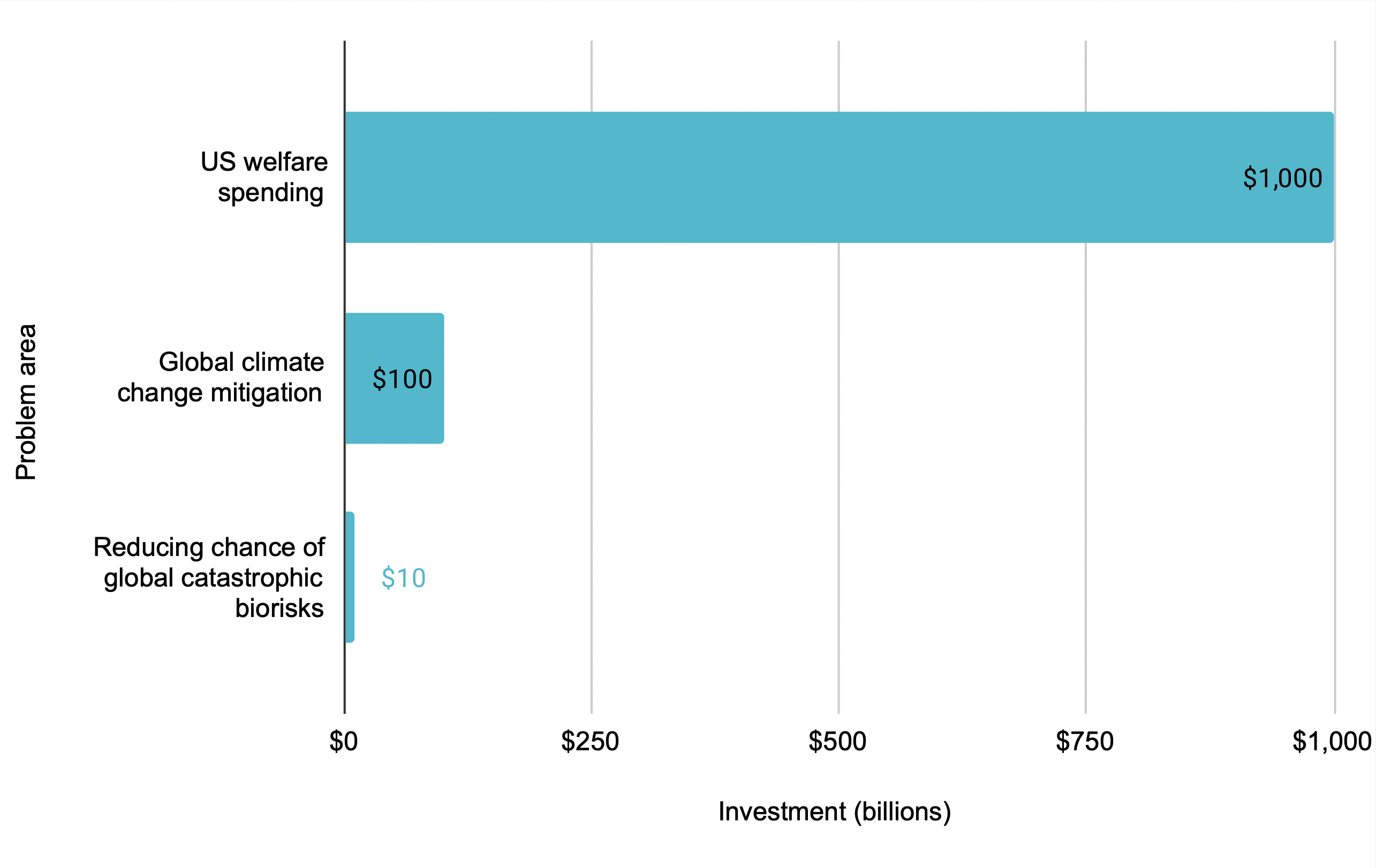

In 2016 we argued that a global pandemic posed a significant global risk, but with around $10 billion spent globally on preventing the worst pandemics per year,1 it was more neglected than climate change or international development (which receive hundreds of billions) — which are in turn far more neglected than education and health in rich countries (which receive trillions).

Why work on issues that are comparatively neglected? At least among issues that are roughly similar in importance, it’s usually harder to have a big impact working on more established or popular issues, because there are probably already people working on the most promising interventions. For this reason, if you’re the 100th person working on a problem, your contribution is likely to make a much larger difference than if you’re the 10,000th.

How much larger? In our view, returns to more work diminish relatively quickly, and approximately logarithmically — meaning that it matters a lot how neglected an area is.

From what we’ve seen, some global issues appear to be thousands of times more neglected than others of similar importance — they receive only a tiny fraction of the resources. This implies that if all else is held constant, work in some areas is thousands of times more effective than work in others.

Inspired by this argument, Cassidy realised that her knowledge as a doctor might be put to even better use in pandemic prevention.

She applied to a master’s in public health programme, and from there was able to get into a biosecurity PhD at Oxford. Since the field of pandemic control was relatively small before COVID-19, she was able to advance quickly. When COVID-19 broke out, she was ready to advise the UK government on policy ideas to control COVID-19, as well as how to prevent the next (potentially much worse) outbreak.

The importance of working on neglected issues means that following your current passions could easily point you in the wrong direction. You’re most likely to stumble across the same issues everyone is already talking about, which will usually be among the least neglected. The best options are probably unconventional.

Which issues might be even more neglected than pandemics?

Three separate surveys of AI researchers at the top machine learning conferences (NeurIPS and ICLM) in 2016, 2019, and 2022 found that researchers believe there’s about a 50% chance that AI systems will exceed human capacities in most jobs around 2060.2 This would be one of the most important events in history.

These same researchers also estimated that if this happened, while the outcome might be ‘extremely good,’ there is also a 5% chance the outcome could be ‘extremely bad’ (e.g. human extinction).3 (That said, it’s unclear how reliable these estimates are — we discuss this more in our profile on preventing an AI-related catastrophe.)

One reason some people are concerned is that it’s unclear whether AI systems will continue to stay aligned with human values as they become more powerful. This could suggest that research into ‘AI alignment’ is a crucial challenge from a long-term perspective.

Since we first wrote about it in 2012, AI alignment has grown into a flourishing field of research in computer science, but it still receives under $100 million in funding per year — about 100 times less than preventing pandemics.

Long-term AI policy — addressing the question of how society and government should handle advancing AI — is even more neglected. (Read more about our case for both.)

How much do problems differ overall?

How important and neglected a problem is multiply together to determine how pressing the issue is overall.

We’ve argued that some issues seem over 100 times bigger than others, and some seem over 100 times more neglected than others.

Since it’s often the most important issues that seem the most neglected, this would suggest that overall you’ll have over 10,000 times as much impact working on some issues rather than others (all else equal).

That said, there are some strong counterarguments to acting as if the spread is this large, which we discuss in our podcast about the key ideas of 80,000 Hours. Overall, we think it might make sense to act like the differences are more like 1,000-fold.

For instance, based on our view of global priorities, we think by focusing on global poverty rather than a typical social issue in a rich country, you might have 10–100 times as much impact, and then by focusing on existential risk, you might have 10–100 times as much impact again.

You might differ from us in which issues you think are most pressing, but we expect you’ll still conclude there are very large differences.

What does this spread imply?

In an ideal world, there would be far more people working on every important social issue. But each of us only has one career, and we’ll all have far more impact if we focus on the issues that are the most pressing for us to work on.

If it’s possible to have 100 or even 1,000 times as much impact per year by changing the issue we focus on, that’s a huge deal. It would probably be the single biggest thing you could do to increase the impact of your career.

If you don’t have the option of making a big career change right now, there’s a lot you can do to support the most pressing issues no matter your current job, through donations, political engagement and mobilising others. But how about working on these issues directly?

Sometimes it’s relatively easy to support a new issue in your existing role. For instance, if you work in media, you might be able to tilt which issues you cover.

Also, many people working in government have significant flexibility about which areas of policy they work on. For example, Clíodhna was working in health policy, but after learning more about AI alignment, she was able to switch to working at the intersection of AI and health.

But even if the switch seems hard, the huge potential gains could mean it’s easily worth it — even if you’d need to retrain, take a more junior role, or test out a role where you’re not sure you’d be a good fit or aren’t sure how to make progress on the issue.

People we advise are often tempted to go for an issue they think is second-tier because it seems easier to enter. But if a top-tier issue might have 10 times the impact, it’s often worth spending some time testing out your fit, even if you’re not sure it’ll work out.

That’s not to downplay the difficulty — orienting your career around a new problem is a big decision. Our main message is that it deserves some very, very serious thought — and much more attention than it normally gets.

Choosing a problem and your career: some common misunderstandings

We discuss how choosing a problem fits into the rest of your career plan and strategy in more depth in our planning process, but here are a couple of quick clarifications.

Do I need to pick an issue right away?

No. The importance of choosing a problem means it’s worth giving yourself time to reflect on your worldview and learn about different issues. People’s views on these questions often develop over the course of several years, and that’s time well spent.

Early in your career (say under 30), it’s often more important to invest in career capital that can give you more leverage to work on whichever issues turn out to be most pressing in the future, when you’re at your peak productivity. In the meantime, it’s usually enough just to have a broad sense of the types of issues you want to work on, and can narrow down later.

One important exception is if you’re considering making a big commitment to a particular issue, such as a specialised PhD, or a particular career track, such as medicine. In this case, we’d encourage you to think more about your choice of issue right away.

And if you’re lucky enough to have already found a promising way to tackle a big problem early on, by all means get started right away.

If you’re later in your career, then the most important decisions you face are probably which issues to focus on, and how to use your existing career capital to contribute to them.

Are you saying everyone should work on the top issue?

No. People often think we think everyone should work on AI, but this isn’t the case.

We think the impact you have over your career depends on:

- How pressing the problems you focus on are

- The scale of the contribution the path lets you make to tackling those problems

- Your personal fit for the path

Although we think the first factor is often the most important, the other two factors also matter a great deal. So, even if you agree with us about which problems are most pressing, it doesn’t mean you should only work on the top one.

For instance, we once advised someone who was choosing between a senior position in international development policy, or starting at the bottom in emerging technology policy. It seemed like they would be able to contribute about 100 times as much in the senior position, and it was also a better personal fit, so we recommended international development over AI.

As another example, we often encourage people with biology backgrounds to work on pandemics over AI due to their better fit.

Coordination and why to spread out over issues

Considering coordination gives us yet more reasons to spread out over a range of problems.

Ultimately, our readers help form a community of thousands of people trying to tackle global problems, which broadly overlaps with the effective altruism community. This community should work on a ‘portfolio’ of issues for several reasons:

- Diminishing returns: there are often a couple of especially good but time-sensitive opportunities within each issue each year. It’s important to have at least some people working on each issue so they’re able to take these.

- Information value: by working on an issue, you learn more about how effective it is. While we think most people should work on the top issues, a minority should spread out over a wide range of plausible priorities in case they discover one is better than our current list.

- Building capacity: for similar reasons, it’s useful to have experts in a wide range of issues to help prioritise further effort, and so we can act more quickly if priorities change.

- Getting more people involved: by working in one area, you might meet people who want to get involved in other areas. This has happened a lot in effective altruism in the past.

The overall picture is that perhaps 50% should focus on the top issues, 30% on secondary issues, and 20% should be spread across perhaps 30+ other promising or important areas.

Here is some data on how our community is currently allocated, and what allocation we think might be ideal. We also have an article that discusses community coordination in detail.

If you see yourself as part of a community aiming to tackle social issues, whether through effective altruism or more broadly, then in order to choose a problem, ask yourself:

- How would the community’s efforts ideally be allocated over issues?

- Where are the gaps, and how can I best move the allocation towards the ideal?

- Where is my comparative advantage compared to other community members?

Likewise, the community as a whole can ask itself the same question: how would the world’s efforts ideally be allocated, and how can we best move it towards that ideal?

So which issues do we think are most pressing?

Given the importance of this question, we dedicate a lot of articles to it throughout our site.

In our career guide, we introduce the case for working to reduce existential risk. Then we give our ranked list of issues.

We’ve also supported the development of the field of global priorities research, which tries to break down and answer the questions involved. For example, how should we allocate resources between reducing the risk of a disaster on the one hand, and preventing a more certain harm on the other? There’s now an institute dedicated to this topic at Oxford.

Despite the vital importance of this research, there are still only dozens of researchers directly focused on it.

Ben Garfinkel was considering a physics PhD, but thought that since so many extremely smart people already do physics research, it would be hard to make a big contribution. He learned about global priorities research through a talk we gave, and after testing it out through a temporary position, decided to switch fields. He then developed important criticisms of arguments for prioritising AI.

This kind of criticism is exactly what we want to see more of. There’s a good chance our views of which problems are most pressing are incomplete or mistaken in some ways. We want people to make the case for alternatives, and find issues we haven’t even thought of yet.

Further reading on how to compare problems

First, you can learn more about the important, neglected, tractable framework:

- Here’s a popular introduction.

- Here’s a more technical discussion of a quantitative version of the framework.

As part of our career planning process, we have an article that guides you through a more comprehensive process for comparing problems.

Here is some more in-depth reading:

- Doing good together: how to coordinate effectively and avoid single-player thinking

- Ben Todd and Robert Wiblin discuss how much problems differ in effectiveness in our podcast on the key ideas series

- Crucial considerations and wise philanthropy by Nick Bostrom

- The moral value of information by Amanda Askell

Read next

This article is part of our advanced series. See the full series, or keep reading:

Notes and references

- Greg Lewis estimates that a quality-adjusted ~$1 billion is spent annually on global catastrophic biorisk (GCBR) reduction. Most of this comes from work that is not explicitly targeted at GCBRs, but is rather disproportionally useful for reducing them. The US budget for health security in general is ~$14 billion. Worldwide, the budget is probably something like double or triple that — so spending that’s particularly helpful for GCBR reduction is probably just a few percent of the total; the spending for explicit GCBR reduction would be much less. See the relevant section of our report into GCBRs, including footnote 21.↩

- The three surveys were:

- Stein-Perlman et al. (2022) (currently only preliminary results are available)

- Zhang et al. (2022)

- Grace et al. (2018)

All three surveys contacted researchers who published at NeurIPS and ICML conferences.

Stein-Perlman et al. (2022) contacted 4,271 researchers who published at the 2021 conferences (all the researchers were randomly allocated to either the Stein-Perlman et al. survey or a second survey run by others), and received 738 responses (a 17% response rate).

Zhang et al. (2022) contacted all 2,652 authors who published at the 2018 conferences, and received 524 responses (a 20% response rate), although due to a technical error only 296 responses could be used.

Grace et al. (2018) contacted all 1,634 authors who published at the 2015 conferences, and received 352 responses (a 21% response rate).↩

- 5% was the median answer according to the 2016 and 2022 surveys (that is, over half of researchers gave an answer higher than 5%). The same question in the 2019 survey found a median answer of 2%.↩