OpenAI: The nonprofit refuses to die (with Tyler Whitmer)

On this page:

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Articles, books, and other media discussed in the show

- 3 Transcript

- 3.1 We're hiring [00:00:00]

- 3.2 Cold open [00:00:40]

- 3.3 Tyler Whitmer is back to explain the latest OpenAI developments [00:01:46]

- 3.4 The original radical plan [00:02:39]

- 3.5 What the AGs forced on the for-profit [00:05:47]

- 3.6 Scrappy resistance probably worked [00:37:24]

- 3.7 The Safety and Security Committee has teeth — will it use them? [00:41:48]

- 3.8 Overall, is this a good deal or a bad deal? [00:52:06]

- 3.9 The nonprofit and PBC boards are almost the same. Is that good or bad or what? [01:13:29]

- 3.10 Board members' "independence" [01:19:40]

- 3.11 Could the deal still be challenged? [01:25:32]

- 3.12 Will the deal satisfy OpenAI investors? [01:31:41]

- 3.13 The SSC and philanthropy need serious staff [01:33:13]

- 3.14 Outside advocacy on this issue, and the impact of LASST [01:38:09]

- 3.15 What to track to tell if it's working out [01:44:28]

- 4 Learn more

- 5 Related episodes

Last December, the OpenAI business put forward a plan to completely sideline its nonprofit board. But two state attorneys general have now blocked that effort and kept that board very much alive and kicking.

The for-profit’s trouble was that the entire operation was founded on the premise of — and legally pledged to — the purpose of ensuring that “artificial general intelligence benefits all of humanity.” So to get its restructure past regulators, the business entity has had to agree to 20 serious requirements designed to ensure it continues to serve that goal.

Attorney Tyler Whitmer, as part of his work with Legal Advocates for Safe Science and Technology, has been a vocal critic of OpenAI’s original restructure plan. In today’s conversation, he lays out all the changes and whether they will ultimately matter:

After months of public pressure and scrutiny from the attorneys general (AGs) of California and Delaware, the December proposal itself was sidelined — and what replaced it is far more complex and goes a fair way towards protecting the original mission:

- The nonprofit’s charitable purpose — “ensure that artificial general intelligence benefits all of humanity” — now legally controls all safety and security decisions at the company. The four people appointed to the new Safety and Security Committee can block model releases worth tens of billions.

- The AGs retain ongoing oversight, meeting quarterly with staff and requiring advance notice of any changes that might undermine their authority.

- OpenAI’s original charter, including the remarkable “stop and assist” commitment, remains binding.

But significant concessions were made. The nonprofit lost exclusive control of AGI once developed — Microsoft can commercialise it through 2032. And transforming from complete control to this hybrid model represents, as Tyler puts it, “a bad deal compared to what OpenAI should have been.”

The real question now: will the Safety and Security Committee use its powers? It currently has four part-time volunteer members and no permanent staff, yet they’re expected to oversee a company racing to build AGI while managing commercial pressures in the hundreds of billions.

Tyler calls on OpenAI to prove they’re serious about following the agreement:

- Hire management for the SSC.

- Add more independent directors with AI safety expertise.

- Maximise transparency about mission compliance.

There’s a real opportunity for this to go well. A lot … depends on the boards, so I really hope that they … step into this role … and do a great job. … I will hope for the best and prepare for the worst, and stay vigilant throughout.

Host Rob Wiblin and Tyler discuss all that and more in today’s episode.

This episode was recorded on November 4, 2025.

Video editing: Milo McGuire, Dominic Armstrong, and Simon Monsour

Audio engineering: Milo McGuire, Simon Monsour, and Dominic Armstrong

Music: CORBIT

Coordination, transcriptions, and web: Katy Moore

The interview in a nutshell

Tyler Whitmer, a commercial litigator and founder of Legal Advocates for Safe Science and Technology (LASST), explains how the California and Delaware attorneys general (AGs) rejected OpenAI’s December 2024 restructure proposal. While he argues the public suffered a “poignant loss” by ceding exclusive nonprofit control over AGI, the AGs forced major concessions that are a significant win for safety and oversight compared to the “flagrant misappropriation” that was originally proposed.

1. The AGs enshrined the nonprofit’s safety mission and control

OpenAI’s original proposal would have sidelined the nonprofit, turning it into a minority shareholder focused on generic grantmaking. The AGs rejected this, forcing a new structure that preserves the nonprofit’s power in several key ways:

- Mission primacy: The nonprofit’s original mission is now enshrined in the new for-profit public benefit corporation (PBC) charter and legally takes precedence over profit motives on safety and security issues.

- Nonprofit control: The nonprofit retains significant control over the for-profit PBC, rather than being sidelined:

- It holds a special class of shares (Class N shares) that gives its board the right to appoint and fire the PBC’s board members.

- It wields direct power over safety decisions through its Safety and Security Committee (SSC).

- AG oversight: The AGs preserved their own authority to regulate the enterprise.

- They now have “additional hooks” through a binding Memorandum of Understanding (California) and a Statement of Non-Objection (Delaware).

- These agreements grant the AGs rights to regular meetings (twice a year with the nonprofit board, four times a year with senior staff) and 21-day notice of any changes that might undermine their monitoring.

- Financial stake: The nonprofit’s stake is far larger than the ~10-20% originally proposed.

- It now receives a 26% stake (worth ~$130 billion) plus an undisclosed warrant for more shares if OpenAI’s valuation increases 10x in 15 years.

- The AGs hired their own independent financial advisors to confirm this was a fair deal for the nonprofit.

- Charter and philanthropy: The OpenAI Charter, including the “Stop and Assist” commitment, was preserved. The nonprofit’s new $25 billion philanthropic fund will be partially focused on “technical solutions to AI resilience,” a more relevant goal than those originally suggested.

2. The nonprofit’s Safety & Security Committee (SSC) has real teeth — but may lack the will to use them

The new structure’s primary safety check is the SSC, a committee of the nonprofit board.

- Explicit power: The AG agreements confirm the SSC has the explicit authority to require mitigation measures, up to and including “halting the release of models or AI systems,” even if those systems would otherwise be permitted for release.

- The “intestinal fortitude” problem: This gives the four-person committee (Zico Kolter, Adam D’Angelo, Paul Nakasone, and Nicole Seligman) enormous power on paper.

- The risk: Tyler worries that these four volunteer corporate directors will face immense commercial pressure from the PBC and investors like Microsoft, and may lack the “intestinal fortitude” to actually use this power and block a multibillion dollar product from being deployed.

- Resource needs: For the SSC to be effective, Tyler argues it must hire its own dedicated, independent staff. The AG agreements allow the nonprofit to get resources, information, and employee access from the PBC via a “Support and Services Agreement” to do its oversight job.

3. The biggest loss: The public’s exclusive claim on AGI is gone

This was the one area where Tyler feels the public lost, as the AGs did not successfully intervene.

- The old promise: The original 2019 structure implied that once AGI was achieved, it would be governed exclusively by the nonprofit for the benefit of all humanity, and Microsoft’s IP licence would terminate.

- The new reality: The new structure allows the PBC to commercialise AGI like any other product, distributing its benefits to private investors.

- Microsoft’s win: Microsoft’s IP rights, which were supposed to terminate at AGI, now extend to 2032, and the company can commercialise AGI independently.

- Tyler calls this a “dramatic change” and a “poignant loss” that goes against the core founding principle of OpenAI.

4. “Scrappy resistance” worked, and continued vigilance is crucial

Tyler credits public advocacy from groups like his (LASST) for giving the AGs the “wind at their back” and “courage of their convictions” to challenge a “really well-heeled opponent.” The fight now shifts to monitoring this new structure.

- New legal tools: The new settlement creates new, and potentially stronger, avenues for enforcement:

- The AGs can now sue OpenAI for violating the explicit MOU/Statement of Non-Objection.

- Because the safety mission is in the PBC charter, a shareholder derivative suit (from a 2%+ bloc of shareholders) arguing the PBC is ignoring safety for profit is now more likely to succeed in Delaware court.

- What to watch for:

- Hiring: Will the nonprofit hire a dedicated CEO or staff for the SSC and its $25B philanthropic fund? (Tyler sees this as a crucial positive signal).

- New board member: The nonprofit must add another director who isn’t on the PBC board. Will this be a true AI safety expert or a “shill”?

- Transparency: Will OpenAI publicly release the warrant details, the SSC’s specific powers (from a referenced September 2023 document), and be forthcoming in the annual mission reports required by the Delaware AG?

Articles, books, and other media discussed in the show

Tyler’s work:

- November update from Not For Private Gain

- Legal Advocates for Safe Science and Technology

OpenAI’s new structure:

- OpenAI announcements:

- OpenAI’s certificate of incorporation of the new nonprofit

- The California attorney general’s memorandum of understanding with OpenAI

- The Delaware attorney general’s statement of non-objection

Others’ work in this space:

- The Midas Project statement on OpenAI’s restructuring

- CEO & Board Conflicts of Interest from The OpenAI Files (from The Midas Project)

Transcript

Table of Contents

- 1 We’re hiring [00:00:00]

- 2 Cold open [00:00:40]

- 3 Tyler Whitmer is back to explain the latest OpenAI developments [00:01:46]

- 4 The original radical plan [00:02:39]

- 5 What the AGs forced on the for-profit [00:05:47]

- 6 Scrappy resistance probably worked [00:37:24]

- 7 The Safety and Security Committee has teeth — will it use them? [00:41:48]

- 8 Overall, is this a good deal or a bad deal? [00:52:06]

- 9 The nonprofit and PBC boards are almost the same. Is that good or bad or what? [01:13:29]

- 10 Board members’ “independence” [01:19:40]

- 11 Could the deal still be challenged? [01:25:32]

- 12 Will the deal satisfy OpenAI investors? [01:31:41]

- 13 The SSC and philanthropy need serious staff [01:33:13]

- 14 Outside advocacy on this issue, and the impact of LASST [01:38:09]

- 15 What to track to tell if it’s working out [01:44:28]

We’re hiring [00:00:00]

Rob Wiblin: Hey, everyone. Just wanted to quickly let you know that The 80,000 Hours Podcast is currently hiring for three new roles:

- There’s a podcast growth specialist: someone focused on packaging, promoting, and distributing the show.

- There’s a research specialist: someone to help make the content sharper and more insightful.

- And finally, a producer or content strategist: someone to plan out episodes and figure out how to fix them in post.

The roles might be done in London, San Francisco, or remotely, and you can find a lot more details in the listings on our job board at jobs.80000hours.org.

If you like the show and would like to make it better, or make there be more of it, or help it find a bigger and more valuable audience, then please do consider applying by the deadline of 30th November 2025.

Let’s get on with the show.

Cold open [00:00:40]

Rob Wiblin: So there’s a sense in which this group of four people, these are incredibly powerful people now, at least as far as AGI and OpenAI goes. If you’re saying that they have full discretion to define what safety and security is, then there’s almost no limit to what constraints they could put on OpenAI’s releases at least.

At the same time, you might worry that while they’re very powerful on paper, the forces that will be brought to bear to discourage them from preventing OpenAI from training or deploying very powerful AI models, they might have to have a lot of intestinal fortitude to be able to actually exercise that authority, and really have the courage of their of their convictions.

Tyler Whitmer: I think it will depend a lot on the people, and how well they perform in these roles. I’m sure you could dream up a better team, but it’s certainly not crazy to think that this is quite a good one. And you know, it’s going to be a really, really difficult job, and one of the things we’ll be looking out for is how are they supporting themselves? Like is there staff that is supporting the SSC, or is this really going to be the obligation of four volunteer corporate directors, which I think would be a big failure mode here.

It is certainly a better world if you take the baseline is what they were planning to do with the December announcement. It is harder to say it’s a great deal compared to the status quo. And I think it’s easy to say it’s just a bad deal compared to what OpenAI should have been.

Tyler Whitmer is back to explain the latest OpenAI developments [00:01:46]

Rob Wiblin: OK, so we are back with an OpenAI emergency podcast, because we have something of a resolution on their attempted for-profit restructure. The attorneys general of California and Delaware have forced through quite a lot of juicy changes on OpenAI’s plans before they would allow the restructure to go through. But OpenAI, for some reason or other, didn’t mention them very conspicuously in the press release about the for-profit restructure, so they’ve gone reasonably underreported on in the press.

And to walk us through all of that, we’ve got Tyler Whitmer, for many years a commercial litigator and then a partner at a major trial law firm. In 2024, he founded Legal Advocates for Safe Science and Technology, which for the last year has been closely tracking OpenAI’s restructure proposal and making public interest submissions to the California and Delaware attorneys general.

He’s a coauthor of an article all about the announcement, about the changes, and what he thinks that people should be looking for going forward — which you could read at notforprivategain.org.

The original radical plan [00:02:39]

Rob Wiblin: So, Tyler, last December OpenAI proposed to completely sideline the nonprofit entity, and basically become a for-profit with roughly no effective constraints. Can you quickly refresh our memories on what they said they were going to do?

Tyler Whitmer: Yeah, I think that’s a pretty fair short summary of their announcement in December, which they just posted on their website. The announcement said that the public benefit corporation, the PBC, would run and control OpenAI’s operations and business, and that the nonprofit would continue to exist, but would only have a relationship with the PBC as shareholder and no other relationship there. So it would be a minority shareholder, not a controlling shareholder.

And the nonprofit was described in that announcement as going to be focused on, I’m quoting here, “charitable initiatives in sectors such as health care, education, and science” — which struck me at the time as not mentioning AI safety at all, or ensuring that AGI benefits all of humanity, which was OpenAI’s nonprofit mission. So it really did seem like it was going to be a complete separation between the PBC and the nonprofit, and that potentially the missions of both would change dramatically in a way that we found very unnerving.

Rob Wiblin: The terminology can get a little bit confusing here. We’re going to be talking about the for-profit entity, which previously was a limited liability corporation, and it’s now going to be a Delaware-based public benefit corporation. Probably I’m going to slip up and refer to it as multiple different things. So it’s PBC, public benefit corporation. We could sometimes just call it the company, the corporation, the for-profit. I think all of those terms are referring to basically the same entity.

Tyler Whitmer: Yeah, that makes sense.

Rob Wiblin: So I want to read the charitable purpose for which OpenAI was established, which we’ve never read on any of the previous episodes, which is something of an oversight.

But the 2020 certificate of incorporation for the nonprofit said:

The specific purpose of this corporation is to ensure that artificial general intelligence benefits all of humanity, including by conducting and/or funding artificial intelligence research. The corporation may also research and/or otherwise support efforts to safely develop and distribute such technology and its associated benefits, including analyzing the societal impacts of the technology and supporting related educational, economic, and safety policy research and initiatives.

The corporation is not organized for the private gain of any person. The property of this corporation is irrevocably dedicated to [these] purposes and no part of the net income or assets of this corporation shall ever inure to the benefit of any director, officer or member thereof or to the benefit of any private person.

So it was a quite aggressive original goal here. As is often the case for when you’re setting up a charity, legally you can’t be saying “…and then we’re also just going to benefit a bunch of investors or ourselves.”

It was very clear that it was focused on AI. And what they were proposing was just making it roughly a for-profit corporation with none of these constraints anymore. Taking this entity, just making it a grantmaking organisation that didn’t even have any particular focus on AI. It was quite an ambit claim in a sense. It was quite a bold thing to put forward to the attorneys general — and I guess basically they have rejected the majority of the stuff that was originally proposed.

What the AGs forced on the for-profit [00:05:47]

Rob Wiblin: Maybe you could go over and quickly list the major changes that the attorneys general insisted on OpenAI implementing and agreed with them before they would allow any of this to go through.

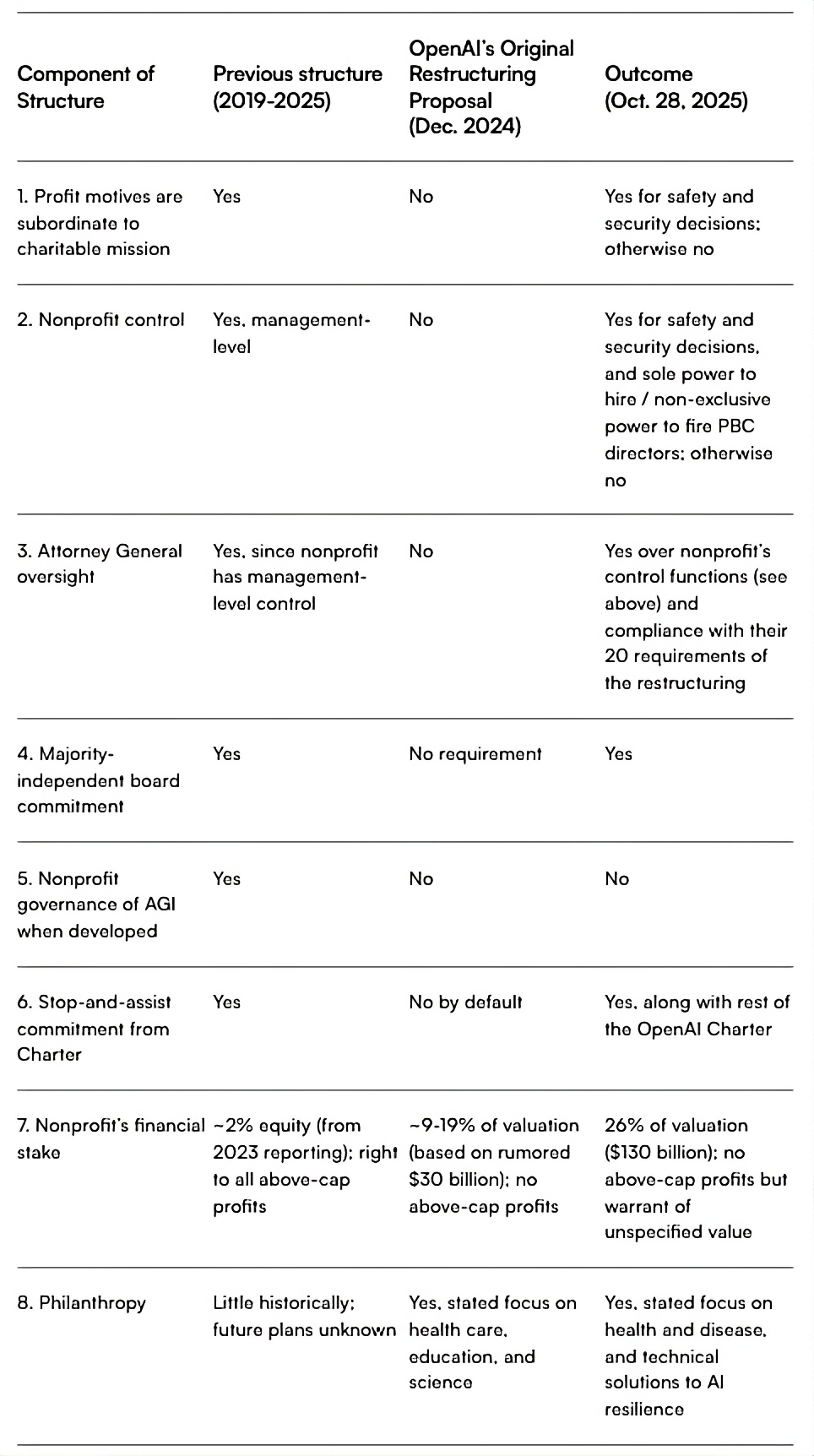

Tyler Whitmer: Yeah, sure. Putting some context around this, that initial proposal or the announcement was pretty bare bones, so we only have a little bit to go on. What I’m about to say is, I’m pulling a lot of this from a statement that we released on the notforprivategain.org website. So folks can go there and click on the third tab. You’ll see a chart that runs through a lot of what I’m about to walk through.

But I do think it’s important to tick through this, so what we’ve done is compared what the existing structure of OpenAI was and how that should have been governed, and then what OpenAI’s proposal in December of 2024 would have changed about that, and then what this new announced restructuring as it’s consummated changes from the December 2024 announcement.

One important point of this is we were really focused on: are profit motives in a restructured, more for-profit OpenAI going to overwhelm the charitable mission? The December 2024 announcement suggested that basically there was going to be nothing that would subordinate profit motives to the mission — that the PBC that would be created would in effect just be a for-profit enterprise, and the mission would not have any primacy over those profit motives.

And in probably the most important piece of this that the AGs have insisted on in the consummated restructuring, the way that this has been announced now, the mission of the nonprofit would be enshrined as the mission of the public benefit corporation, and the mission — at least as it relates to “safety and security” is the verbiage that’s used — will take precedent over profit motives. And this is done in the certificate of incorporation of the PBC — and we can go into detail on that if you want to later — but it’s enshrined in a public document that is difficult to change at the PBC. And we think that’s an important piece of this.

With respect to safety and security, the mission is now definitely in control versus profit motives in the new restructured OpenAI. With respect to everything else, however, it’s not. And that’s an important issue. That’s a problem.

Rob Wiblin: So before, the nonprofit had direct management control: they could basically obligate OpenAI the company to do anything. Now they no longer have that direct control, but they have a Safety and Security Committee — which can, on security and safety issues, impose its will on them as it defines it. They’re retaining a kind of special right on safety and security issues in particular, while relinquishing control on many other things.

Tyler Whitmer: That’s right, yeah. In the existing structure, that existed before this restructuring was consummated, you had management-level control: total control of the nonprofit board over the operations of the for-profit enterprise at OpenAI. The December announcement would have stripped that completely, effectively: the nonprofit would have had no control, based on our reading of the December announcement, over the for-profit enterprise at all.

And the new announcement has control by the nonprofit over the PBC as it relates to safety and security through the Safety and Security Committee, as you just mentioned.

There’s also control at the level of the board. The current announcement gives the board of the nonprofit — through a special class of shares, the N class of shares — the right to elect the board members of the PBC. So they have control over who sits on the board, and although non-exclusive, the right to fire board members of the PBC as well. So while it has less control in the current situation than it did prior to the restructuring, it has a lot more control than it would have had, had they gone through with the December 2024 announcement.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. So the nonprofit board can appoint and fire members of the for-profit PBC’s board, but if two-thirds of the general investors in the company want to fire a board member, they can do it as well. So it’s not an exclusive right to fire them.

I guess we thought that with the original proposal that the attorneys general would lose almost all ability to have oversight of OpenAI the company. What’s changed on that?

Tyler Whitmer: Yeah, I think this is important. The attorneys general have some power just by virtue of being the chief law enforcement officers in their state. Setting that aside, they have a lot of extra power over public charities in their jurisdictions — and in particular in Delaware: under Delaware law, it’s very clear that the Delaware attorney general is the regulator that polices charities’ adherence to their missions.

Charities’ missions generally are for the benefit of the public. So the charity’s board has a special fiduciary duty under Delaware law to govern the charity in a way that benefits their fiduciaries: the beneficiaries of their mission. And under Delaware law, it’s the Delaware attorney general that then polices their adherence to that fiduciary duty. So there’s a lot of oversight of charities that exist at the AGs, much more power over charities than they would have over regular for-profit institutions.

So in the existing setup before the restructuring, the AGs had an enormous amount of authority over OpenAI, because OpenAI was a charity and the for-profit was completely managed by the charity. Therefore, because the charity had a lot of power over the for-profit, the AGs had a lot of power over the charity and therefore had a lot of power over the for-profit, much more than they would with an independent for-profit.

The December announcement, by separating the charity from the for-profit enterprise, would have drastically reduced the AGs’ authority to regulate the for-profit enterprise, because the AGs’ authority is hinged to the nonprofit aspect of the organisation. So by separating those two very much in the December 2024 announcement, you would have seriously undermined the ability of the AGs to manage anything in the for-profit, or oversee anything in the for-profit.

And, like we’ve been discussing, there’s now kind of a hybrid situation. It’s somewhere in a grey area between what used to be and what was announced it was going to be. We’re now in a place that’s in the middle. The nonprofit’s control over safety and security issues now gives the attorneys general significant power in that domain right over the for-profit of the PBC. So the nonprofit, by virtue of having control over the charity’s authority to govern the PBC’s safety and security measures —

Rob Wiblin: So does the AG.

Tyler Whitmer: Right. Exactly, precisely.

And then also just the AGs have basically entered into agreements with OpenAI. In the case of Attorney General Bonta in California, it’s an actual memorandum of understanding that’s signed by both parties. In the case of Delaware Attorney General Jennings, it’s a statement of non-objection, I think is the way it’s phrased. But they basically said, contingent on OpenAI doing the following things, then we, the attorneys general, are not going to object to this restructuring or recapitalisation going through the way that it’s been proposed. And those contingencies that are baked into those agreements with the attorneys general are now additional hooks that the attorneys general have to oversee the PBC that they might not otherwise have if the PBC were an ordinary PBC not subject to those requirements.

So in those two ways, the attorneys general have preserved a lot of authority and oversight power over the PBC — by virtue of the nonprofit’s control of the PBC, and by virtue of the agreements they’ve had with OpenAI that are contingencies for the restructuring or recapitalisation to go forward.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah, if you wanted to dive into the next level of weeds here, the key things to read would be the memorandum of understanding and the agreement between OpenAI and the AGs of California and Delaware.

There’s a bunch of other oversight requirements:

- They get to meet twice a year with the nonprofit board to discuss any of their concerns.

- They are meeting four times a year with senior staff at the company to discuss things that they will agree on ahead of time, and they have to be informed about relevant information so they can decide what issues they want to explore.

- They also have to be notified 21 days ahead of time — it’s very carefully worded, which I think betrays a slight degree of nervousness on the part of the attorneys general — about any changes that might undermine their ongoing ability to basically monitor either of these organisations, changes to the agreements between them.

So I think that the AGs are aware, they know that OpenAI could try to wriggle out of this, and they are trying to make sure that they get a heads up if any of that starts to happen, so they can intervene and go to court and say no.

Tyler Whitmer: Yeah, that’s absolutely right. And I would read the twice a year and four times a year requirements as a floor, not a ceiling. That’s the bare minimum that is required of OpenAI to fulfil their obligations to the AGs would be that level of communication. I think the AGs could ask for more, and it would be really difficult for OpenAI to say no to a request like that.

So viewing this from the outside, I think it would be the right way to think of it as that being sort of a floor rather than a ceiling. And there’s a lot the AGs could ask for that it would be hard for OpenAI to say no to.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. Another big change is I guess OpenAI never said that they were going to get rid of the stop-and-assist commitment or the rest of the OpenAI charter that they published many years ago and still had on their website. But the fact that they never reassured anyone that they were keeping any of these things, and the fact that it’s such an abnormal thing for a company to have, made everyone kind of assume that probably it was going to be removed or changed or weakened — but it’s being republished, or it’s being going to be published by the public benefit corporation.

It sounds like the AGs are going to hold them to sticking to the OpenAI charter and the stop-and-assist commitment: that if another company looks like it’s about to develop AGI ahead of OpenAI, then they will stop racing and competing, and simply assist them to do it safely — a remarkable commitment really I think for any company to make. It’s still going to be in there nominally that that is something that they would be open to, and I guess kind of required to do under that circumstance. Is there anything you want to add there?

Tyler Whitmer: Yeah, that’s right. And at least someone in Attorney General Jennings’s office was quoted in the press as saying they viewed this as an important concession that they got. So they really were focused on the charter.

The only other thing I’ll say about this, that just adds to what you’ve been saying, is that there’s more to the charter than the stop-and-assist clause. It talks about the spirit of cooperation, it talks about broadly distributed benefits, long-term safety. And I think those things are also important guiding principles that now are much more enshrined than they were before.

I would love to have seen some of this actually incorporated into the certificate of incorporation of the PBC, and it has not been. This could have been more effectively incorporated into the restructured enterprise, in my view. But having it even referenced in the requirements of the AGs was more than I was expecting, like you said. And I think a great sign, both from the point of view of what the restructured organisation will consider itself to be bound to, and I think it’s also a great signal for what the AGs find important.

So to the extent that this is both guiding the enterprise, and then, if it’s not guiding the enterprise, it will be guiding the attorneys general in their oversight of the enterprise — which is the next best thing, I think — I think it’s great that this got included in the restructuring.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. What are the other big changes from the original plans?

Tyler Whitmer: The announcement in December would not have required the board of the PBC to be majority independent, and there’s no underlying requirement under Delaware law that the board of a for-profit organisation be majority independent. And the AGs have required a majority independent board as part of the restructuring, so I think that’s good.

We can quibble — and you and I can talk about it more later if you want to about what “independence” means and how important this is in practice versus paper — but I do think it’s an important concession, and something that wasn’t necessary that the AGs insisted on.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. So OpenAI is defining “independent” as not owning a direct equity stake in OpenAI. And the thing that we would quibble about — maybe more than quibble — is that several members of the nonprofit board, and probably members of the company board in future, have indirect financial interests. They stand to benefit or lose, depending on what OpenAI does, to the tune of potentially very large sums of money, even though they don’t actually own the company. So that’s a potential weakness that I’d be interested to contemplate whether the AGs might take more of an interest in this definition of independent going forward.

Tyler Whitmer: The AGs require more than the statutory definition of independence in their concessions they got from OpenAI. So I think it’ll be important to see how much they push. It’s not just independent in the sense of they’re not an employee of the company, like Sam Altman is not an independent because he’s the CEO of the organisation. So I think the fact that the AGs required something beyond independence in the traditional sense does hint at them at least having some hook to keep the board from including people who are really compromised by non-direct conflicts of interest, if you will.

And I’ll just like shout out The Midas Project has done great work at The OpenAI Files, documenting some of the indirect conflicts that exist. They’ve done a great job highlighting that.

But stepping beyond independence, we talk about the financial stake that the nonprofit has in the PBC. I think this is a hard one, because we don’t know all the facts that are necessary to really evaluate this. And I say that from both sides: we didn’t know all the facts of what the real financial stake was in the world before the restructuring, because there’s some uncertainty about how the profit caps had evolved over time; and we don’t know the current financial stake after the restructuring that the nonprofit has, because a lot of that is contingent on a warrant for future shares that the nonprofit holds with respect to the PBC, and the details of that warrant have not been disclosed as far as I’m aware.

But in terms of the actual just equity stake, like common share equity stake of the PBC, the December announcement, the rumours circulating at the time would have given the nonprofit something like a $30 billion stake in the PBC — which again, would have been its sole relationship to the PBC. And that’s, depending on whose valuation you’re looking at, something like 10% to 20% of the value of the PBC at that time.

And the restructuring as it’s been closed gives the nonprofit a $130 billion stake. That’s about 26% of the common shares of the PBC. And again, there’s a warrant that would provide the nonprofit with some undisclosed amount of additional shares should the PBC’s valuation increase by 10x over the next 15 years, I think is the terms of the warrant. So we kind of know what the strike of the warrant would be, but we don’t understand what the nonprofit would receive if the PBC were to grow at the rate that’s specified in the warrant.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. So we’ve gone from estimating that they would get 10% to 20% of the financial value of the company up to 26%, plus some unspecified amount: What’s in the box? Who knows?

This is if OpenAI succeeds to a significant extent — its value increases 10x in 15 years, which I think is very plausible, even if you’re not incredibly AGI pilled, it being quite a successful tech business. And the fact that they’re not saying how much it is makes me think that probably it’s not very much. Otherwise they would be more excited to tell us. Is there any other reason why they might not want to disclose?

Tyler Whitmer: Yeah, I don’t know. You’d think they would have to disclose it to investors before they invested.

Rob Wiblin: Because it would dilute it.

Tyler Whitmer: Right. And that’s the only other constituency I could imagine them catering to here, other than the public. So it’s unclear. I mean, they do say something in their announcement about what the warrant would mean. It says something like, between the existing stake and the warrant, the nonprofit “is positioned to be the single largest long-term beneficiary of OpenAI’s success.”

So that’s OpenAI’s announcement describing the warrant. Obviously that could mean a lot of different things too. You know, whether they’re not saying more because they would be embarrassed in public with what they had to say, I don’t know. Or maybe there’s some commitment from other investors as part of the deal, that they’re meant to keep that quiet. It’s interesting that it’s not public. We would call on them to make it public. I think it’s important for the public, as the beneficiaries of the nonprofit’s mission, to understand exactly what we’re getting out of this.

So we think it would be important for them to be more transparent about that. But you know, I’m not a finance guy and I’m not an economist, but I can imagine a world where if you put together the existing stake with the warrant, depending on what the warrant is, maybe there’s a world where that’s like a great approximation of the profit caps as they existed when they were first instituted in OpenAI — in which case, I think probably most people would be happy with that situation. And there’s a world in which it’s a total fig leaf and it’s basically meaningless and valueless, in which case that’s obviously an enormous theft.

Rob Wiblin: Misappropriation.

Tyler Whitmer: Yeah, misappropriation of resources from the public. And that would be a huge shame. And given what we know now, as far as I know, we can’t tell.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. This is one where people have had to throw up their hands and say, because not enough information is public, we can’t say whether this is a fair amount of compensation or not. I guess the fact that the AGs have been this involved suggests that there’s been at least some oversight to make sure that they’re not being enormously shortchanged.

But of course, these things are incredibly hard to estimate, so it could be that if the board had been laid out differently, such that the nonprofit had even better lawyers representing its interests, even better financiers representing its interests versus the people behind the company, then maybe they would have managed to negotiate for a higher price.

Tyler Whitmer: Yeah. For what it’s worth, it’s been reported that the nonprofit was represented by investment bankers and finance people in addition to lawyers. And there was reporting that the Delaware AG’s office hired their own financial advisors to advise on the deal. If you read carefully Attorney General Jennings’s statement of non-objection, at the beginning there’s something like, “We’re only approving this to the extent that our financial advisors say that it’s a fair deal on the economics for the nonprofit.”

So there’s at least some encouraging signs that there were serious people who viewed themselves as having a fiduciary duty, or viewed themselves as representing the interests of the attorney general and therefore the public, and who were taking a close look at this. So I think it would be hard for the warrant to just be embarrassingly small in that context, but I’m not sure I have faith that it would be as large as I would want to approximate the caps.

Rob Wiblin: The maximum amount possible.

Tyler Whitmer: Precisely. It is the subject of a negotiation.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. That is substantially reassuring. Maybe I’m a cynical person by nature, but there is a lot of encouraging stuff here, as we’re going to talk about. And the fact that the AGs had independent financial advisors who said that they thought that this was fair is definitely a lot better than the alternative.

Tell us about the final, really significant change in the plans.

Tyler Whitmer: Yeah, I think probably the biggest piece of this… Well, there’s two things we haven’t discussed yet that I think would be important, one of which is the governance of AGI, of artificial general intelligence, and the other one is what’s the nonprofit going to do? I’ll do the philanthropy first, because I think that there’s more to say maybe, or at least it’s a sadder story about the AGI bit.

But the philanthropy bit: OpenAI historically has just not done a lot of grantmaking and traditional philanthropy stuff. And the December proposal, as we discussed a little bit earlier on, suggested that AI safety was not going to be a priority of the philanthropic activities of the nonprofit going forward. It was going to be more of a standard sort of corporate foundation, kind of doing good stuff that I think is good for the world, but I don’t think was really tied directly to OpenAI’s mission of ensuring AGI benefits humanity.

And the new announcement suggests there’s going to be a $25 billion investment across two different areas, one of which is health and disease — and I take that to mean accelerating the ability of society and science to deal with health and disease issues — and then the other one is technical solutions to AI resilience.

I think OpenAI said a little bit about what that means, including in their announcement livestream, where Sam Altman and others described there being sort of a security layer over the internet now that didn’t exist in the sort of wild west days of the early internet. And that’s just made the internet much more functional as a place to do business and interact with one another. And there needs to be that kind of a layer that society has, to ensure that we can have AI integrated into society, but in a way that supports humanity.

I’m probably paraphrasing, I might be getting some of that wrong, but that at least sounds a bit like more traditional AI safety work than the announcement in December 2024. And that’s heartening to see that there’s going to be at least some focus on making sure that the systems that OpenAI and others are developing are able to be implemented in society in a way that supports human flourishing. So I think that’s great.

You know, what exactly that looks like we don’t know. And the concerns that I had — you know, putting on my cynical hat, which is the hat I wear most of the time too — I think, is there really going to be enough independence between the nonprofit and the PBC so that the nonprofit would feel free to do AI safety type research or AI resilience research, if you want to use that terminology, that would actually create a commercial hit to the PBC?

Rob Wiblin: Create headaches for the company.

Tyler Whitmer: Precisely. So I think if we end up in a world where that independence really does exist, then this seems great. And it seems like it’d be a huge boon to putting dollars behind important research that will help us on AI safety. To the extent that that independence doesn’t exist, probably still helpful on the margin, but maybe not as much as one would like.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah, so it’s totally unsurprising to me that the attorneys general completely objected to the idea that all of this money would just go towards generic education and health projects. That had nothing to do with its original stated charitable purpose. That would be a very odd outcome.

It’s a little bit surprising that they’ve waved through what it sounds like is medical research and biomedical research. I think a very legitimately worthy cause, and there’s a lot of really high impact stuff there, but it is somewhat divorced — unless you’re using AI or something in order to do the research, it’s a little bit of an odd fit. But they’ve allowed that to go through. The AI and societal resilience stuff does clearly fit within the original remit.

It’s maybe a bit of a shame that they haven’t cast a wider net there to consider all of the resilience and risks and upside potential, the entire project of figuring out how do we integrate AGI and eventually superintelligence into society to ensure a good outcome. But it wouldn’t surprise me that if they wanted to, they could fund almost anything in that broad class on this basis, and I don’t imagine that anyone would have legal standing to object.

Tyler Whitmer: Yeah, I think that’s right. Also this is an initial announcement of an initial philanthropic investment in an initial two areas. So I think it’s encouraging that they’ve at least included the AI resilience piece in this, but this is another one where it feels like a floor, not a ceiling. And we can hope that they do more in areas that really feel meaningful to the mission. And if they don’t, we, along with hopefully many others, will be out there putting pressure on them, and putting pressure on the AGs to put pressure on them, to do more in areas that we think are really important from an AI safety perspective.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. Just on the cynicism point: it was rumoured that Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI, would get potentially a large equity stake in the company as it became a public benefit corporation. But he’s not getting any such stake. I guess we did flag that this was a possibility, maybe laughed at it in previous episodes. So I should say we were wrong or plans changed.

I think inasmuch as people think that he’s a fantastic tech CEO, then he can negotiate for a higher salary and potentially negotiate for equity in the company going forward, but he’s not being handed a bunch for his… I don’t know on what basis you would do it, which is maybe why it’s not happening, but on the basis of his past work.

Tyler Whitmer: Yeah, that’s my understanding. I don’t know any more about it than that, honestly.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah, OK. But the one area where the AGs didn’t intervene to a significant extent is on the question of nonprofit oversight and governance of AGI when it’s developed. Tell us about that.

Tyler Whitmer: Yeah, so I think that the way that the description of the enterprise functioned prior to this, and before the announcement in December 2024, it was understood that OpenAI reaching AGI or achieving AGI was sort of this inflection point where a lot of things would change.

When they negotiated their original deal with Microsoft, once OpenAI announced that they’d achieved AGI, basically Microsoft would have no IP rights with respect to AGI: that would solely be something that was governed by the nonprofit. And in that initial setup, then part of the benefiting all of humanity is both making sure that AGI is safe and doesn’t harm humanity, and then also that the use of AGI at the time that it was created would be for the benefit of humanity instead of just commercial interests.

And in the December announcement, I think you could just say basically that there was no mention of this, and therefore you would assume no protection of AGI in the way that we’re describing now.

In the new announcement, the nonprofit and the AGs will still have the oversight authority we’ve been describing for the last several minutes, including post AGI. It’s not like that’s going to go away after AGI is reached. But there’s no clear delineation that I’ve seen in the current restructuring that would take AGI and put it in the purview of the nonprofit, as opposed to allowing the PBC to commercialise it, in part for the benefit of the PBC’s investors.

So to the extent that the previous understanding was that AGI would be this sort of separate and unique thing that would be solely in the nonprofit, for the benefit of the beneficiaries of the nonprofit’s charitable mission, that no longer seems to be the case — that post AGI, the PBC would still be able to commercialise AGI in ways that would benefit presumably both the public but also the PBC’s investors.

And we have some information in an announcement about the way that Microsoft came around to agreeing with the restructuring, and that describes some changes to the deal between Microsoft and OpenAI. We don’t know much about this — we don’t have the underlying documents, obviously — but the announcement describes the fact that Microsoft, after the restructuring, would be able to maintain its IP rights to AGI up to 2032, and that it would be able to commercialise AGI independently under that situation to whatever OpenAI the PBC is doing.

So this is a really dramatic change, and I think probably one of the more upsetting or disappointing aspects of the restructuring as it’s been approved. Really, OpenAI’s charitable mission is to ensure that AGI is safe and benefits all of humanity. And it’s sort of hard to imagine how one can ensure that that’s the case when you’re granting a licence to use it to an organisation that you don’t control. You know, the overall control rights that have been agreed to help blunt this loss to some degree, but it is still, I think, a big loss from the perspective of the public, and one that we should be sad about, frankly.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. So in summary, the nonprofit board is giving up the ability to control AGI once it’s developed, and they’re giving up a bunch of other direct management control of the company. But they’re maintaining some kind of permanent reserve powers over safety and security issues. Their financial stake is changing from one where they get a large amount of return if the company is super successful, but not much otherwise, to one where they get a flat 26% stake and then some other options if it succeeds, as yet unspecified. And I guess they’re now planning over time to trade that financial stake to engage in philanthropy on these various different topics.

Why do you think OpenAI didn’t mention almost any of this stuff in their announcement? Is that the for-profit almost immediately kind of resisting ongoing nonprofit oversight? Or perhaps they just don’t want this to be as salient to investors, because investors would rather that they just be completely independent and have no nonprofit oversight. It’s a little bit surprising to me that I think from the public’s point of view many of these things are very good and desirable, but they were seeming to kind of bury the story.

Tyler Whitmer: Yeah. I mean, I would be speculating. I don’t know exactly why they chose not to make a bigger deal out of it. I do think that in some sense the AGs have been out there trumpeting their wins. They obviously have a smaller microphone than OpenAI does these days. And so you can go out and find this information. And y if you look at our letter, we link to the certificate of incorporation of the new PBC as well, where you can find additional information if you’re the kind of person who wants to dig through dense corporate filings.

But yeah, they have not trumpeted these obligations in a way that makes you think they’re trying to make a case to the public, I suppose is one way to look at it.

Scrappy resistance probably worked [00:37:24]

Rob Wiblin: I don’t want to belabour the point, but I suppose the fact that the attorneys general have forced through so many changes to the original proposal suggests that you and me and the thousands or millions of other people who read about this and thought it sounded pretty bad, pretty inconsistent with our understanding of charity law, were kind of right. And when the authorities looked at it, they said, “No, this is unlawful. It would be irresponsible of us to wave this through.”

I think it’s heartening that despite the fact that some of the most powerful entities in the world wanted more or less to misappropriate tens or hundreds of billions of dollars of resources that had been pledged to the general public, they were not able to pull it off. The attorneys general said, “No, this isn’t allowed. What are you doing?” and have ended up with a deal that I guess people could argue it’s still maybe unfair in certain respects. I think it’s actually kind of unclear. I could see some people saying that actually, on balance, all of these things are a kind of reasonable change as a package. And some people have argued that. But either way, the kind of flagrant misappropriation was just flat-out disallowed.

Tyler Whitmer: Yeah, I think that’s a good way of looking at it. A thing I’ll add to that is that I think it also speaks to the power of somewhat scrappy resistance, right? I don’t know that each of these issues would have gotten the salience with the attorneys general that they did, or that the attorneys general would have felt that they had the courage of their convictions to the extent that they did to sort of push back against a really well-heeled opponent.

So an addendum to that I will say is that I think it speaks to the power of public advocacy as a tool to nudge things in a good direction. And I think that’s something that AI safety folks should keep in mind. This work really matters, and it’s important.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. So the attorneys general said that… I guess the California one said that they’ll be paying close attention to whether OpenAI is fulfilling the memorandum of understanding, and the Delaware attorney general said to the press that, “We’ve never been afraid to go to court before to defend the public interest, and we wouldn’t be afraid to do so here.”

Is that basically the recourse here? If OpenAI doesn’t honour the spirit or the word of this, then the attorneys general would take them to some court or other and say they’ve broken our contract?

Tyler Whitmer: Yeah, that’s correct. I think they would have the right to sue for breaching the memorandum of understanding or the statement of non-objection or however it’s phrased, if that were the case.

And Attorney General Jennings would have the authority to sue for breach of fiduciary duty, the special fiduciary duty of the nonprofit to the mission’s beneficiaries. So to the extent that Attorney General Jennings feels that the nonprofit is not doing its job with respect to safety and security, and managing the affairs of the PBC where those issues are involved, then she could sue to argue that the board of the nonprofit had failed to do its job in that respect. So we’ll continue to have that oversight.

I think there’s other constituencies that arguably would have a chance here to affect things. One thing that we’ve noted before in our discussions of these issues is the fact that there hasn’t been a reported case of a shareholder derivative suit of a PBC enforcing the PBC’s mission. That’s just not a thing that’s happened, but it is theoretically a thing that could happen. And importantly, by having the certificate of incorporation make it clear that the nonprofit mission is that the mission is the only thing that should be considered when it comes to safety and security, I think makes it more likely for a shareholder derivative suit against the PBC for failing to adhere to the mission. It would make it more likely for such a suit to be effective as a tool for enforcement.

So the fact that that is the way they’ve structured safety and security with respect to the PBC, having it baked into the certificate, and having it say very clearly that when it comes to safety and security, the mission is all that matters, and that the shareholder pecuniary interests don’t matter and other stakeholders don’t matter, I think will make it more possible for there to be some pushback from PBC shareholders who care more about the mission than they do about their share price, and would be willing to argue that the PBC should be doing more on safety and security than they currently are. I think there’s at least some avenue there for enforcement beyond the AGs.

The Safety and Security Committee has teeth — will it use them? [00:41:48]

Rob Wiblin: That raises the fact that we’ve now set up a system where the nonprofit has a Safety and Security Committee that has the exclusive right to actually have really quite strong controls over what the company does on security and safety issues. So it says in the agreement here, the one with California:

The SSC has and will continue to have the authority to require mitigation measures—up to and including halting the release of models or AI systems—even, for the avoidance of doubt, where the applicable risk thresholds would otherwise permit release. The NFP [not-for-profit] will provide advance notice to the Attorney General of any material changes to the SSC’s authority.

So they could block product releases, and I think probably also prevent training, I would guess by extension, if they thought that training something was dangerous. But that means that it’s plausibly an issue of hundreds of billions of dollars would be at stake. Trillions of dollars, conceivably down the line. What is the actual legal authority of this handful of people, currently four people? What counts as a safety and security issue? Do we have any more clarity on that? Do they decide what a security and safety issue is? Does the attorney general decide?

Tyler Whitmer: I think there’s at least an argument that the SSC itself, the committee itself, gets to decide for itself what falls within its purview, at least based on the wording of the attorney general’s requirements here.

So that gives even more power. It makes it even more important who those people are and how serious they are about doing their jobs on the SSC. And the other powers of the SSC, there’s some uncertainty here due to lack of transparency. So there’s a reference to a September 2023 “Unanimous Written Consent” of the Board of Directors that outlines the powers and authority of the SSC as it exists now. And they’ve sort of said, “You’re going to continue to have this thing in the way that it exists now.”

So another thing that I think it would be great to get more transparency on, and we would call on OpenAI to provide more transparency on, is what the exact powers are. What does that UWC say about what the powers and responsibilities that the SSC has had since September of 2024? Because that is going to to some degree influence or set the standard for what their powers and authority are going forward. We know a little bit about it, because of the text that you just read in the attorney general’s requirements, but we don’t know all the details there, and I think we should.

Rob Wiblin: So this group of four people is:

- Zico Kolter, an academic, a professor at Carnegie Mellon in ML, very strong AI chops and understanding, and does actual safety and security research.

- Adam D’Angelo, the Quora cofounder, who also I think runs Poe, which is a major OpenAI customer.

- Paul Nakasone, a retired US army general who’s focused on cybersecurity in particular

- And Nicole Seligman, past president of Sony, a major figure in Sony and I think some other companies over the years.

These are incredibly powerful people, at least as far as AGI and OpenAI goes. And there’s a sense in which, if you’re saying that they have full discretion to define what safety and security is, then there’s almost no limit to what constraints they could put on OpenAI’s releases, at least.

At the same time, you might worry that while they’re very powerful on paper, the forces that would be brought to bear to discourage them from preventing OpenAI from training or deploying very powerful AI models might make it… They might have to have a lot of intestinal fortitude to be able to actually exercise that authority and really have the courage of their convictions — especially if Microsoft has hundreds of billions of dollars tied up in this: they’re known for aggressively pursuing shareholder value, might be a polite way of describing it.

What do you make of it overall? Is the SSC overpowered or in practice do you think it might be sidelined a bit?

Tyler Whitmer: I think it’ll depend a lot on the people and how well they perform in these roles. I think that they are set up to have a lot of power and be able to exercise a lot of control here. But that’s authority that’s granted to them; it doesn’t necessarily dictate what they’ll do with that authority.

So to your point, I think it really does require a lot of these people. I can’t imagine many people had heard Zico Kolter’s name before this — and as you say, if you’re someone who believes in transformative AI and believes that OpenAI is in the lead in terms of reaching something like transformative AI, then Zico Kolter suddenly has an awful lot of power in that context. And how he wields it is going to be really important for how things go with OpenAI, and, to the extent they have control over how things go for everybody, how things go for everybody.

Rob Wiblin: I suppose in my dream fantasy world or something, we’d put four people in this group who just happen to agree with all of my opinions or something like that. But in the real world that we live in, where people have all kinds of different opinions, and you want to choose respectable people who have relevant expertise that can make good decisions rather than just reflect Robert Wiblin’s random opinions, it’s not such a bad list of people.

We’ve got an academic who has a really deep understanding of ML. We’ve got someone who has experience in OpenAI over many years: Adam’s been on the board for a long time, and I guess experience in the tech industry. Someone who has military government experience, and an understanding of cybersecurity issues in particular as a focus is something that’s quite relevant to AI. And someone with deep corporate and legal experience.

It’s quite complementary. I think none of these people are on the record as either being super worried about safety and security or being dismissive of it. They are maybe all open to being convinced about how serious the security and safety concerns are. So in a way they’re set up fairly well, apart from the fact that there will be people who really might want them to not intervene in OpenAI.

Tyler Whitmer: Yeah. And just to flag it, Sam Altman used to sit on that committee when it was first formed, and he’s since stepped down and I think that’s good. I think it’s really important that he not be on that committee, since that committee will in large part be a check on his power. So I think that’s really important.

And I think you’re right. I’m sure you could dream up a better team, but it’s certainly not crazy to think this is quite a good one. And it’s going to be a really difficult job. One of the things we’ll be looking out for is how are they supporting themselves? Is there staff that is supporting the SSC, or is this really going to be the obligation of four volunteer corporate directors? Which I think would be a big failure mode here.

So that’s going to be a big thing that we’re on the lookout for. How aggressively are they asserting themselves? And then are they making some of that public and being transparent about when they’re stepping in and helping make decisions? All these things are important.

Rob Wiblin: If they hire dozens of assisting technical advisors and staff to help with the work of the Safety and Security Committee — you know, tracking what’s going on in OpenAI, making recommendations about what they should require versus not — that wouldn’t feel at all excessive to the job. It’s a very big and very important job, if you believe OpenAI is a big deal, as I imagine all of these people do.

I guess they haven’t said anything about whether they plan to staff up and use any of the money that they’ve gotten or plan to have by liquidating some of their stake to actually hire the necessary support, so it’s not just incumbent on four volunteers.

Tyler Whitmer: There’s an important piece of this that is not directly tied to the SSC, but if you look at the requirements that the AGs are requiring, there is a section in those requirements that talks about what resources the nonprofit can require of the PBC to fulfil the nonprofit’s mission — which of course would include the work of this SSC, which is a committee of the board of the nonprofit.

It’s number 11 if you look at Attorney General Jennings’s statement of non-opposition: there’s reference to a “Support and Services Agreement” that I think is a TBD document — this is a pretty common document in corporate mergers, for example — but it talks about a Support and Services Agreement between the PBC and the nonprofit that would basically give the nonprofit access to resources at the PBC for the purposes of doing the nonprofit’s job, which would include its oversight of the PBC.

So in addition to potentially being able to hire to support its work, there should be a provision in that Support and Services Agreement — which again, we don’t have access to, so we don’t know the details of it — but in theory at least, the SSC would have both information rights… So right now, Zico Kolter, as chairman of the SSC, does not sit on the PBC’s board. He only sits on the nonprofit’s board. But the requirements of the AG would give him the right to observer status on the PBC’s board, and he would have all the information that the PBC board gets. So when he’s making decisions as chair of the SSC, he has access to all that information. Of course, the other members of the SSC sit on both boards, so by some definition they already have access to that information.

But I think an important thing that isn’t obvious if you’re not sort of parsing this, is that the Support and Services Agreement should in theory give the SSC resources via the PBC. So they could say, “You, PBC employee: you need to come help us do our work at the SSC to oversee the PBC. We need access to these models, we need access to this compute in order to do our jobs.” And depending on what the terms of the SSA is, at least in theory, there will be some resourcing of the SSC that doesn’t require them to go out and hire new staff.

Rob Wiblin: So it means that they can’t be sidelined if they want to intervene, or probably if they want to be active and they’re deeply concerned about something, it would be hard for the PPC to brush them off in any way.

Tyler Whitmer: Right. But again, all this cashes out on the initiative and, as you said, intestinal fortitude of the folks sitting on the SSC. I think that’s really where this grounds out in a meaningful way. They’re given access to an authority, but it’s up to them to then exercise that authority and grab that access.

Overall, is this a good deal or a bad deal? [00:52:06]

Rob Wiblin: So is this a good outcome relative to the status quo that we had 12 or 18 months ago? Maybe I’ll just read a comment that someone in the audience sent in making the case that actually maybe not only is it OK, but maybe this is an improvement:

The previous structure was nominally better on paper: the nonprofit had comprehensive control in theory, but it was illusory in practice. OpenAI had been functioning like a traditional tech company for years, and the nonprofit “control” was a fiction everyone had stopped pretending to believe. The new structure arguably matches reality better, and it’s also been intentionally agreed. The nonprofit technically has less power, but people might paradoxically take that power and responsibility more seriously now. At the very least, the AGs are tracking that it’s their responsibility to oversee OpenAI, that model safety is of the utmost importance, and maybe model releases will even need to be halted! While arguably they weren’t really paying attention to this before, even if they should have.

What do you make of that?

Tyler Whitmer: That’s not a crazy reaction. I wish we lived in a world where the statement about how OpenAI had been functioning like a traditional tech company for years and no one had cared about that, I just wish that part weren’t true. But wishing doesn’t make it so.

So if you take as your baseline that the December 2024 announcement was just like a codification of what was kind of happening anyway, in terms of OpenAI just like acting like a for-profit that sort of had a nonprofit attached to it in some weird way, then I think the outcome is a lot better than that.

I think it just depends on what your baseline is for comparison. If your baseline for comparison is an idealistic view of what OpenAI was meant to be when it was founded in 2015, I think this is in some sense a catastrophe. We’ve just lost a lot, as the public, of what we should have had if OpenAI had been the better version of itself it was always supposed to be.

But I think that description of the situation does reflect a lot of the reality that we have now, which is that it was unclear a year ago whether the AGs were paying attention, or really were looking at OpenAI at all from the perspective of, “We are the regulators of public charities, and OpenAI is a public charity that we should be regulating.” And now they definitely are. Not only are they looking at it, but they’ve laid out very specifically hooks that they have into the company to assert that regulation in multiple ways.

So to some degree, I think there is at least a non-crazy argument that this restructuring makes things better than the existing status quo as the baseline. It is certainly a better world if you take the baseline as what they were planning to do with the December announcement. We’re certainly in a better world than that. There’s no doubt about it. And I think there’s at least a reasonable argument that we’re in a better world even than we were before that announcement.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah, it’s night and day compared to the original proposal. Let me steelman the case that this is conceivably even better than a realistic vision of what OpenAI could have become on a somewhat different track.

So let’s say that you’re on the board of OpenAI, and you have confidence in the Security and Safety Committee, the SSC, actually are going to step up, do their job in an assertive way, take a great interest in what OpenAI is doing. And inasmuch as OpenAI is doing irresponsible things, tell them that they have to stop and they have to invest in various mitigations before things will be approved. So you think the SSC is actually a good arrangement, maybe because you trust the people or you trust the process.

Then you might think perhaps OpenAI is the best bet out of the different companies. Does Google have something equivalent? Maybe this is a stronger set of constraints than the one Google is facing. I guess maybe you would have a harder case arguing that this is better than Anthropic. But I don’t even know whether Anthropic technically has a set of four semi-independent people who can block releases. I think they maybe have something along those lines, but you still might think maybe this is a better process. And certainly you might think this is better than xAI, which hasn’t really shown a tonne of interest in these issues. So then you’re like, “I would like OpenAI to be a frontier AI company, because I trust us to do a job that’s as good as others, possibly better.”

In that case, insisting that the nonprofit retain control of AGI once it’s developed indefinitely, that the for-profit investors get somewhat sidelined in that situation, perhaps it’s an unrealistic ask if you want to attract the level of investment, the hundreds of billions, perhaps trillions of dollars in future that will be required to pursue this business vision. Perhaps that would be nice to have if you could get it. But if you do that, you’re probably going to fall behind, because it’s just too much to ask for all of those investors to swallow.

So you accept this kind of middle ground where you’ve retained control on a narrower set of issues that were most important to you, you’ve relaxed control on some other areas, and said AGI is also going to be used for profit. And inasmuch as the Safety and Security Committee approves that, that is kind of tolerable, maybe even good. So this is like the best middle ground that keeps OpenAI competitive while still having a group of people who could tell it to stop.

What do you make of that?

Tyler Whitmer: Yeah, I think if you take as true some of the conditions you put there, like if you take it as true that OpenAI has this better safety setup, and that they’re going to be a more responsible actor to the extent that you’ve got multiple AI companies reaching for AGI here, that’s not crazy. Maybe it is a fair trade to trade away the exclusive governance of AGI for they are continuing to be able to compete at the frontier and hire the talent they need to hire and get the investments they need to get.

I guess my counterargument to that to some degree is like, they didn’t seem to be having a lot of trouble getting investments or getting talent under the existing capital structure. And I know they’ve said in public that that was starting to become a friction they were running up against. I just don’t have the information I would need to evaluate whether that’s actually true or not.

So to some degree there’s an empirical question here that underlies whether that steelman version that you’ve just laid out makes sense. And I think it’s an empirical question that we probably don’t have the data to get to the bottom of.

But it’s not crazy. Like I said, when you read out that audience member’s description of the situation, I think that’s a pretty reasonable take to have. It doesn’t strike me as completely unreasonable.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. I don’t quite buy into that story, because I suppose at the end of the day, I don’t really believe that OpenAI is a more safe and responsible AI company, or I don’t think it has demonstrated itself to be a more responsible AI company than Anthropic. And maybe probably not than Google either. I probably would rate it somewhat behind those two.

However, if you’re on the inside, and you could see that while it maybe has a checkered history so far, you think it’s going to be on a better upwards track from here: it’s recommitted to all of these things, we’ve now settled where the balance is going to be struck…

I mean, through all of this time I’ve said many critical things about the corporate chicanery at OpenAI, they nevertheless continue to churn out some great safety and security and alignment research. They have some of the best people in the game over there. They continue to innovate on the model, on model specs, what they could be, how they should develop in future, having transparency on that kind of thing. I guess they have a different approach to Anthropic, which has its pluses and minuses, but I think serious people think that there’s a lot to be said for the OpenAI approach.

In the past they’ve had a very strong governance and policy team, but they still have some great people there and put out interesting work, and they’re providing access to third parties to do inspections on models before they were released, and to look into the deceptive behaviour. We’ve got an episode coming up with an external auditor who was doing research on an OpenAI model before it came out.

So on the technical side, there is substantially good stuff going on, and I guess it would be great if the board would double down on that and say, “We want that to be an even bigger part of the organisation, and we certainly don’t want it to be reduced, and it should grow proportionate to the risk as we get closer to models that actually pose as a serious kind of systemic hazard, which probably current models don’t.” That’s what I imagine could be going on in their heads.

Tyler Whitmer: Yeah. I think my personal view on this is probably more cynical about OpenAI than you and I have been saying right now. So if it were up to me, I really think that forcing OpenAI to be the thing that it was set out to be from the beginning would have been a better outcome for the world than what we have now. That’s my personal view. And I’m speaking just for myself — not for Page [Hedley] or the Encode folks or anyone else involved with Not for Private Gain — this is just me, Tyler. That’s my view, but that’s mostly coloured by my perception of how OpenAI has changed over the last 18 months or so and how I see them.

We could go chapter and verse of this, but I think it’s probably off topic and it would take a lot of time. But that’s my quick take on it: my view is that OpenAI’s mission is to ensure that AGI is safe and benefits all of humanity. Not to be the first to AGI. And so to the extent that they’ve decided that the only way they can ensure it is to be first, I’m not sure I agree with that take. And I think that’s where I ground out on this question.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. The original vision was pretty amazing. It’s hard for anything to compete with the ideal of what OpenAI perhaps would have become, and perhaps could have been on a different timeline.

Tyler Whitmer: It’s amazing, but also maybe naive. So maybe this was an inevitability or something too. I don’t know.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. One of the most striking things you say in the article is that it’s a “poignant loss” that the nonprofit will now no longer have exclusive control of AGI once it’s developed. What’s the case that this is a very bad outcome, something we should be really concerned about? And what’s the case that it’s not so important, or perhaps it was not realistic to maintain?

Tyler Whitmer: I think a lot of the answers to both of those angles depends on what AGI means. And that’s obviously a hotly disputed and contested terminology. So to the extent AGI means truly transformative AI — in the “What meaning does money have in the future?” sense of transformative — then I think part of OpenAI’s founding mission was to keep that power out of a profit-motive-driven organisation.

So we talk about it as a poignant loss precisely because this was something that was at the core of the organisation that is now lost. The whole point of OpenAI was to make sure that whoever develops and controls AGI is not a profit-driven organisation, and that is now gone. So I do think that is a real loss.

What that means for the future, I can imagine the PBC is required to at least consider its public benefit mission in making decisions around AGI. Microsoft continues to have a licence through 2032, assuming we get to AGI between now and then. But I assume that’s a non-exclusive licence, so it’s not like they’re going to take away the right of the PBC to do nice things with AGI.

So I think it’ll come down to, again, the management of the PBC. One problem that you could imagine OpenAI solving for at founding here was that having AGI in the power of an organisation that was required to maximise shareholder value, that was the misalignment at the core of the thing that made that outcome so terrible. Putting that in a PBC at least gives PBC management the ability to not focus exclusively on shareholder value. They at least have the option of focusing on the mission. And the mission of the PBC is again the mission of the nonprofit.

So it is a loss. The degree to which it is a loss I think is yet to be seen, and we won’t know unless and until AGI is reached and we’re living in that world and seeing how the PBC responds to its rights and responsibilities in that world.