Most people report believing it’s incredibly cheap to save lives in the developing world

One way that people can have a social impact with their career is to donate money to effective charities. We mention this path in our career guide, suggesting that people donate to evidence-backed charities such as the Against Malaria Foundation, which is estimated by GiveWell to save the lives of children in the developing world for around $7,500 [Update: now $2,300 as of 2020].

Alyssa Vance told me that many people may see this as highly ineffective relatively to their optimistic expectations about how much it costs to improve the lives of people. I thought the reverse would be true – folks would be skeptical that charities in the developing world were effective at all. Fortunately Amazon Mechanical Turk makes it straightforward to survey public opinion at a low cost, so there was no need for us to sit around speculating. I suggested a survey on this question to someone in the effective altruism community with a lot of experience using Mechanical Turk – Spencer Greenberg of Clearer Thinking – and he went ahead and conducted one in just a few hours.

You can work through the survey people took yourself here and we’ve put the data and some details about the method in a footnote.1 The results clearly vindicated Alyssa:

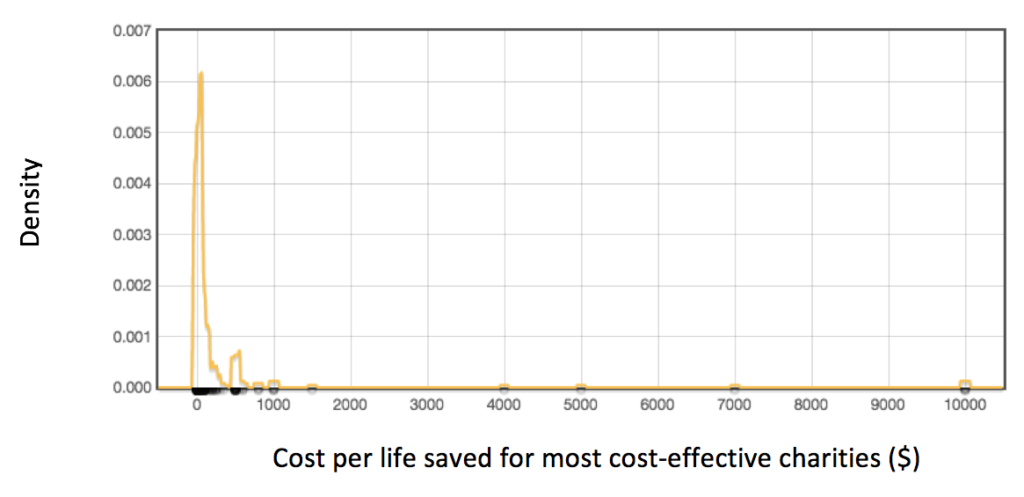

It turns out that most Americans believe a child can be prevented from dying of preventable diseases for very little – less than $100. In fact, 40% of people believed the ‘most effective charities’ could save a life for under $10 – less than a hundredth of what we believe to be the true cost. 3% believed a life could be saved for under $1! A minority thought it would cost much more – 5% gave an answer over $1,000 – which pushed the average to around $500:

| Cost to prevent one child from dying for… | ||

|---|---|---|

| A typical charity | The most cost-effective charities | |

| 10th percentile | $5 | $2 |

| Median | $40 | $25 |

| Mean | $488 | $360 |

| 90th percentile | $920 | $500 |

We asked about both typical charities and the most cost-effective charities, and as shown in the table, people thought they were roughly equally effective.

We have good evidence that the cost to save a life for typical charities is not anything like as low as $40. If this were true, then such charities spending $1 billion each year would be able to save 25 million lives – a sixth of all births globally, and more children than are actually dying of easily prevented diseases. There simply aren’t enough lives being saved in total for figures like that to add up.

On the other hand, we can’t know for sure that the estimates for “the most cost-effectiveness charities” are wrong. There could be some high-risk high-return projects, for example those conducting scientific research, that ultimately will save lives for less than $100 each. That said, we don’t know any reliable way to save lives for that price – GiveWell has spent a decade searching and hasn’t come close to finding anything that cost-effective which isn’t already being funded.

We should keep in mind that this survey only elicited people’s snap judgements. Most Americans don’t have considered views on the issue of charity cost-effectiveness, and many commented that they were “pulling numbers out of the air”. A different wording of the question might have elicited different answers (e.g. how many people would be prevented from dying, who otherwise would have died, if you donated $1,000 to a charity delivering health services in the developing world).

Furthermore, there are ways the survey questions could be interpreted differently by different people. Respondents may have read the question as asking about the average effectiveness of charities in the developing world in general, rather than the cost of saving an additional life by increasing spending. Some programs that are already well funded, like basic vaccinations, will save lives more cheaply than the best incremental spending opportunities available. Some may also have been thinking of the unit cost of delivering a vaccine that ‘could’ save a life, rather than the total cost of distributing a sufficient number of vaccines to save one person who otherwise would have died. Consistent with this, one respondent noted:

“$10 seems like a pretty good number to include enough food and medicine for 1 child”

But even given these limitations there are some things we can learn from this survey:

- Many people donate a small fraction of their income, despite claiming to believe that lives can be saved for remarkably small amounts. This suggests they don’t believe they have a duty to give even if lives can be saved very cheaply – or that they are not very motivated by such a duty.

- If we write articles observing that the cost to save a life is in the thousands of dollars, readers are more likely to be disappointed than impressed by the opportunity this presents. This disappointment might be avoidable if we compare that number to the cost of saving a life in a rich country, or the incomes for wealthy people. This is something that could be tested in future surveys.

- A number of people cited charity advertisements suggesting that even small donations ‘could’ save a life as informing their estimate. For instance, two respondent explained:

“I gave this amount [Ed: $10 per life saved] because of advertisements I have seen on t.v. and the claims they make as to how much it cost to save a child’s life.”

“I remember seeing commercials saying for only $1 a day or $30 month you can save the life of a child. So I just guessed and picked half the amount.”These statements are technically true, in the same sense that a lottery ticket ‘could’ be worth millions of dollars. Unfortunately, using language like this runs the risk of misleading people. Peter Singer‘s famous essay The Drowning Child and the Expanding Circle, which is still widely circulated today, includes a quote of this kind which could convince people that work on global poverty is more effective than it actually is:

“we can all save lives of people, both children and adults, who would otherwise die, and we can do so at a very small cost to us: the cost of a new CD, a shirt or a night out at a restaurant or concert, can mean the difference between life and death to more than one person somewhere in the world…”

- The median person believed that the ‘most cost-effective charity’ was 66% more cost effective than a ‘typical’ charity. This stands in contrast with the widespread belief in the effective altruism community that the best charities are much more effective than typical ones – 10-fold or more. This probably goes a long way towards explaining why most donors do not put large amounts of effort into trying to find the very best charities to give to: they only expect modest improvements in value for money from doing so.

- Survey takers were asked to explain how they thought the best charities were outperforming typical ones. The most common answers focussed on operational efficiency and the so called ‘overhead myth’:

“lower overhead. workers get paid less, less administration”, “The less cost effective charities waste money on non essential things”, “Lower overhead costs”, “Typical charities waste money on advertising and paying their high-level ’employees’ large sums of money.”

By contrast at 80,000 Hours we believe most of the differences are driven by what kind of service the charity offers, whether that service actually helps people in a significant way, and how much it costs per person who is reached.

So Alyssa was right that most folks are inclined to think global health charities are much more cost-effective than I do. Thanks to Spencer Greenberg for running the survey. Hopefully we can use Mechanical Turk to deal with questions like this again in future.

Notes and references

- The code and data are public.

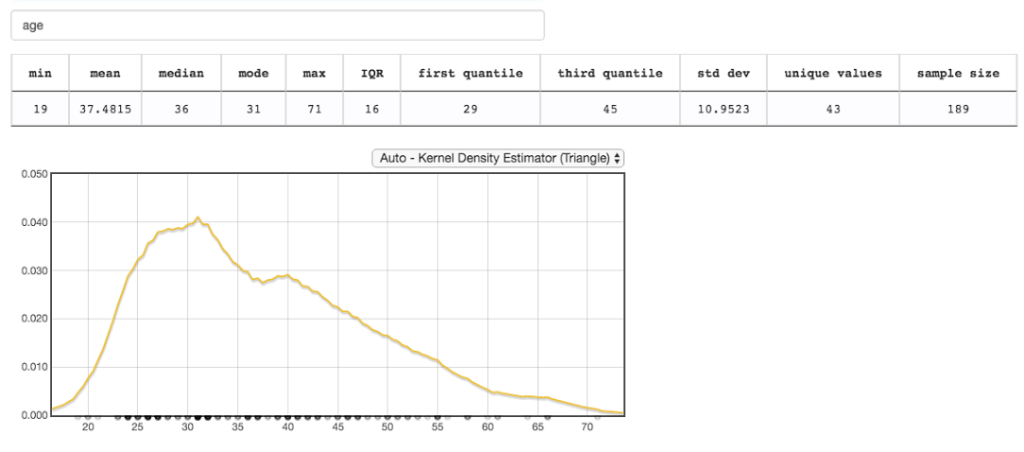

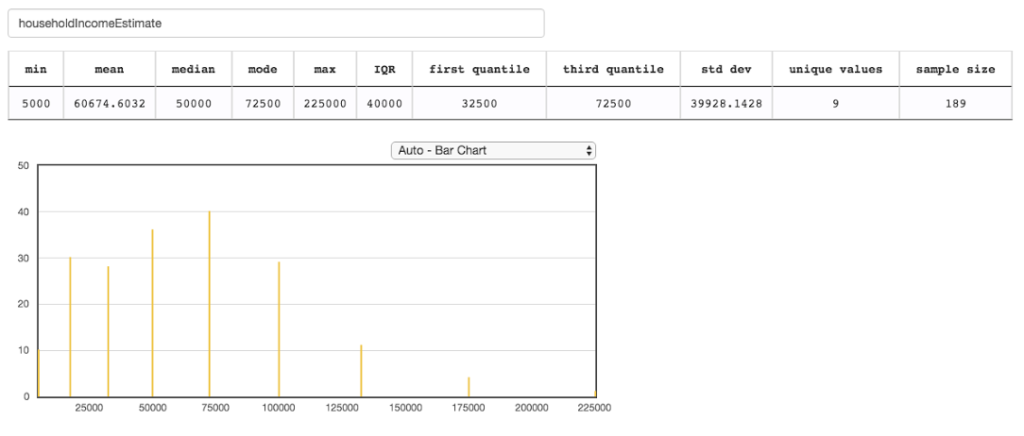

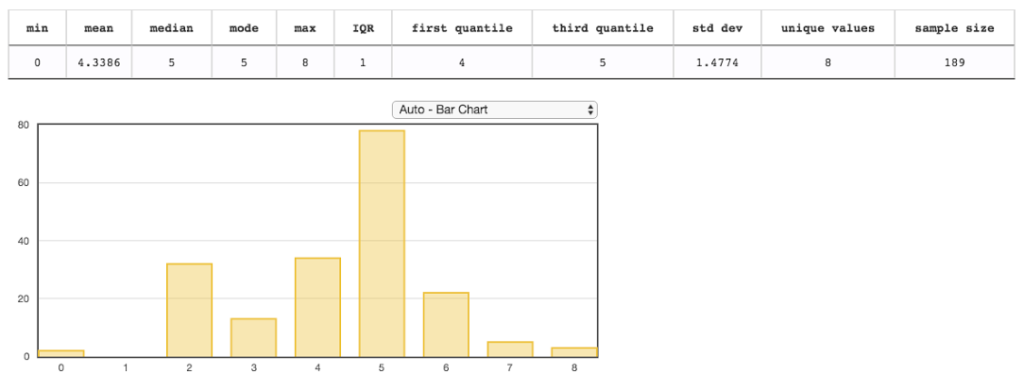

The Survey was of 261 people, 189 of which finished and were included. 184 of those were in the USA. Question order was randomised. We collected data on age, education and income and found they weren’t so different from the population as a whole:

For education,

0=No schooling at all completed

2=Completed only high school or the equivalent (for example: GED), no college

5=Completed bachelor’s degree (BA, AB, BS or other)

8=Completed doctorate degree (PhD, PsyD, EdD or other.)

Sample was 51% female.↩