Transcript

Rob’s intro [00:00:00]

Rob Wiblin: Hi listeners, this is The 80,000 Hours Podcast, where we have unusually in-depth conversations about the world’s most pressing problems, what you can do to solve them, and whether you’re more likely to have a heart attack if you live in a county or a state. I’m Rob Wiblin, Head of Research at 80,000 Hours.

Is war on the decline?

Getting the answer to this right really matters.

The US and the PRC are for better or worse entering a period of renewed great power competition, with Taiwan as an obvious possible trigger for war between them, and Russia is once again invading and attempting to annex territory from its neighbours, something that has a very 19th century feel to it.

If war has indeed been gradually going out of fashion for the last few hundred years, we might reassure ourselves that however troubling the current situation feels, fingers crossed modern culture should continue to throw up power barriers to another global war like those of the past.

But if we’re as war prone as ever, one need only inspect the record of the 20th century or the 19th century, or the 18th century, to feel a suitable level of fear about what might be in store for us in the 21st century.

In 2019 political science professor Bear Braumoeller wrote a book analysing the question of whether war is in long-term decline, titled Only the Dead: The Persistence of War in the Modern Age.

It was in part a response to Steven Pinker’s book The Better Angels of Our Nature, and other optimists who think that modern ways of reasoning and learning about the world, and modern moral attitudes, are gradually reducing the proclivity of states to launch wars.

As you’ll hear, unfortunately Bear does not agree with this.

Given this is a live controversy with smart people on either side, I approached this episode wanting to get into the weeds in order to help me figure out what I actually think about this question personally.

That means that when we turn to Bear’s data analysis, we really get into the nuts and bolts — things like how exactly the number of wars is coded when there are more than two countries involved, how he corrects for the fact that his graphs test many different hypotheses at once, and the results Bear got for at least four different plausible measures of warlikeness.

This is the best discussion of these specifics that I’m aware of, so I’m really proud of what we’ve managed to put together here.

But that is on the challenging end, so the show’s producer Keiran did a little reorganisation of the conversation to put the most engaging and general interest topics first.

So first up, we’ll give a short summary of the conclusions of Bear’s data analysis in Only the Dead.

But we’ll then press pause on that, and discuss the ideas and values of the enlightenment, and whether we should naturally have expected them to reduce rates of war since 1700.

We then push on to what Bear thinks is the real primary driver of rates of conflict, which political scientists call ‘international orders.’ To illustrate that, we go through two international orders from the 19th century which I knew very little about before reading his book — the Concert of Europe and the Bismarckian system. It’s great stuff if like me you enjoy history.

We then talk about what can be done to reduce the risk of war today if Bear is right that the risk remains troublingly high, and it’s the nature of international orders that do the most to determine their prevalence in any given period.

We then loop back and dive deep into Only the Dead, discussing the datasets he used, the specific results he got for different measures of warlikeness, the power law for deaths in war, the biggest weakness of the analysis, and quite a few others things.

I hope that section can provide a lot of clarity for people who, like me, have found it very confusing how much disagreement there seems to be on this issue.

All right, without further ado, I bring you Bear Braumoeller.

The interview begins [00:03:32]

Rob Wiblin: Today I’m speaking with Bear Braumoeller. Bear is a computational social scientist and a professor in the Department of Political Science at Ohio State University, where in 2020 he founded the social science research lab known as MESO, which stands for Modeling Emergent Social Order. He’s been studying issues of war and peace for over 30 years. In 2013, he published The Great Powers and the International System, and in 2019, he published Only the Dead: The Persistence of War in the Modern Age, which is the topic of today’s conversation.

Thanks for coming on the podcast, Bear.

Bear Braumoeller: Thank you so much. I’m very glad to be here.

Rob Wiblin: I hope we’re going to talk about whether war is in decline and what factors most influence its prevalence. But first, what are you working on at the moment, and why do you think it’s important?

Bear Braumoeller: What am I working on at the moment? That’s a few things.

First of all, with my research lab, which you just mentioned, I’m working on studying the relationship between international order and international conflict. It’s important in part because preliminary results show that there’s a big relationship between order and war, but there aren’t very many studies, and there isn’t very much theory. And so as a result, it’s difficult to translate that relationship into anything approximating actionable foreign policy advice, for example.

Second, I’m here now in Oslo, Norway at the Centre for Advanced Study with a group of people who are spending the years studying the causes of escalation and warfare. That’s important because that was something else that came out of the book: I realised that some wars get really, really big and other wars don’t, and the extent to which wars can escalate is really shocking. You read the book, so you know that. At the end of chapter 5, I was trying to find a silver lining and say something optimistic, and I just sort of threw in the towel. I’m like, “No, this is really bad. It sucks. There’s nothing good to say about escalation.”

But one thing that a few of us have realised is it’s just incredibly understudied. We study war initiation; we don’t study escalation. So there’s a group of statisticians and social scientists here who are getting together for an entire year to hash out our differences, in some cases, and try to get a better handle on why it is that some wars get really big and others don’t.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah, fantastic. It seems like your research project is taking all of the things that you weren’t sure about at the end of Only the Dead and trying to answer them. And some of them are very difficult questions, so you need a whole team in a research lab just to make some progress on it.

Bear Braumoeller: Right, exactly. It’s accumulative research. It’s funny, I used to tell people that I study the academic equivalent of bright shiny objects, because I would just study whatever I was drawn to. But yeah, this is definitely an extension of the work that I did in Only the Dead.

Only the Dead [00:06:28]

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. Well, let’s talk about Only the Dead. What prompted you to write the book?

Bear Braumoeller: Well, it’s sort of funny. I wouldn’t call it statistical analysis, but I had played around with the data about trends in warfare before, but only in the context of teaching. When I teach classes on war, one of the things that I tell my students is, “You may not know this, but there are data on wars, and people actually analyse data on wars, and you can get some interesting findings out of them.” And so during the first lecture, I would just talk a little bit about some of the things that we can try to figure out using data on wars. And one of them was: are we seeing a rise or decline in conflict? I mostly showed them why that was a hard problem to answer, rather than trying to come up with a comprehensive answer.

But the funny thing is that it’s not the way that political scientists study war. We try to look for primarily things that cause war or ways to predict war. We never really look at questions like “Is war on the decline?” And so I never really thought of that as a very interesting exercise. But then Steven Pinker’s book came out, and I realised people are really interested in this question. And so I thought, “I have to get this book. I have to take a look and see what it says.” And I got it, and I started reading it, and I thought, “Wow, I am really not satisfied with these answers.” Not because of what the answers were, but because of the way in which he arrived at them.

So this started out as a paper. I wrote a conference paper. This is what academics do when we get annoyed about something: we sit down at the computer and start typing away. So I started writing a paper. I invited Steven Pinker to an Author Meets Critics panel, which ended up being cancelled. So I just kept working on the paper, and it kept getting longer and longer.

And at one point I was fortunate enough to have a conversation with Dave McBride, who is the editor at Oxford University Press. And I said, “I’ve got this paper that I’m wrangling, and I think I might be able to turn it into a book — or I might have to, if I want to say everything that I want to say.” And he had just read Better Angels of Our Nature. He had some of the same reactions I did. He was over-the-moon excited about having me write this book.

And this is something that not a lot of people know: academic books do not get marketed the same way that trade books do. They’re just completely different streams.

Rob Wiblin: Do they get marketed at all?

Bear Braumoeller: Mostly to university libraries, and directly to other academics. So my first book, I naively expected to be able to walk into the local Barnes & Noble and find it on the shelf. And I was sorely disappointed. And so I talked with Dave, and he said, “If you think this debate deserves to be in the public sphere, we can market this as a trade book. The challenge is you have to write it in plain English. You can’t write it like an academic would.”

Now, this was actually a fun opportunity for me, because before I became a political scientist, I wanted to be a writer. I actually very much enjoy writing, and I’m painfully aware that social science has done terrible things to my writing. So this was a great opportunity to try to undo some of those things and write for a general audience. So I thought that this sounded perfect.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. Did the book get as much public attention as you were hoping? I mean, it’s a super hot topic. As I’ve learned preparing for this, it’s a controversy in academia, but it’s a controversy in academia that has definitely spilled over into the public sphere.

Bear Braumoeller: Right. It did, and it didn’t. So COVID definitely refocused people’s attention. This was something that I think publishers noticed across the board: that book sales were down in general.

Rob Wiblin: I see.

Bear Braumoeller: On the other hand, Ukraine has sparked more interest in the topic, I think. But definitely, it’s night and day compared to a regular academic publication, and it certainly seems to have gotten a lot of people talking, which is great.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah, I think you’ve done an excellent job explaining really quite difficult social science analysis. In a way that, if you had no knowledge or no experience with these issues, it would be heavy going. But if you do have some idea about statistical analysis, or you have some preexisting interest in social science, I think you should definitely be able to follow it, and you’ll just learn an enormous amount reading the book. So if anyone does enjoy this interview, I can definitely recommend going away and reading it. Before we dive into the substance, where does the title come from? Only the Dead.

Bear Braumoeller: This is a quote from George Santayana, who’s a philosopher who is mainly known for his quips, I think. And one of the things that he said was, “Only the dead have seen the end of war.”

Rob Wiblin: I see. OK.

Bear Braumoeller: And that’s funny, I don’t know why, but in the military, that’s attributed to Plato a lot. And I didn’t want to screw it up when I put the attribution in the book. So I did some double checking and there’s no evidence that Plato ever said that.

But the reason for the title: I thought Better Angels was a fantastic title. I really like that part of the book. And I wanted something with an equivalent kind of literary pedigree that would convey the opposite message. At the same time, as you saw going through the book, I don’t want to be confrontational. I just want to try to answer this question. So there’s a book that came out I think last year called The Darker Angels of Our Nature by a group of historians. And that was a title that crossed my mind, and I just let it cross. I thought this is much more about the question of whether war is in decline than it is about Steven Pinker per se.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah, absolutely. It might seem like we’re picking on Steven Pinker a little bit as this goes on, or focusing on him a little bit — but I suppose that’s the consequence of being enormously successful, and getting your book out and your message out so much: you become the standard bearer, I suppose, for a set of views that are actually pretty mainstream already.

Rob Wiblin: So, the many findings in the book are presented, as I was saying, with substantial complexity and subtlety. And it’s going to take a while to explain many of your concerns with past research, then lay out your methodology, and then work through the various different tests and specifications that you provide us with. But so the audience can’t miss it, is it possible to summarise in a few minutes the key bottom lines that you really wanted people who read the book to remember and come away with?

Bear Braumoeller: Yeah, I wish there was just one bottom line, but there are a few. The first one is that there are a lot of reasons to be sceptical about the data and arguments that have been presented in favour of the decline of war argument. And this was a big part of my frustration in reading Better Angels in particular. I was looking forward to these nuggets of data, and the statistical tests, and so on and so forth, and I just didn’t see that.

Some other scholars have accused Pinker of cherry-picking the data. I didn’t do that in the book, but I’ve read that criticism, and I don’t think it’s completely unfair. Just for one example, he provided a graph of war in decline from a conference paper that never got published, and I dug up the conference paper and it was one of six graphs, and it was the only one that showed war in decline.

Rob Wiblin: It doesn’t seem fully evenhanded.

Bear Braumoeller: That’s one issue. Another is that the analysis of the data is really lacking. And this is a point that Nassim Taleb has made often and at length in particular: that there are no actual tests of the argument, in the sense of a formal statistical test that would help you distinguish signal from noise. That’s what statistical tests do. So it looks a lot more impressive, I think, to people who don’t do data analytics than it actually is to the people who do. That’s one bottom line.

Rob Wiblin: Right. OK, what are some other key messages?

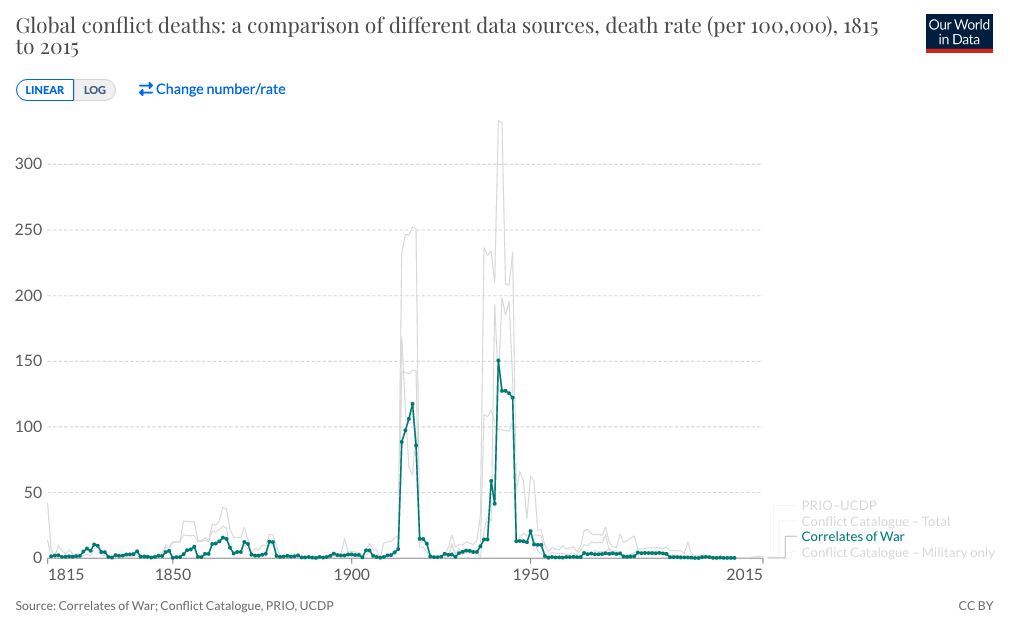

Bear Braumoeller: The second bottom line is that when you do test the argument that war is in decline, it’s really hard to find support for it. And I was clear about this in the book: I wanted Pinker to be right. My hope was that I was going to find trends that were going to support the argument. But I looked at three different meanings of the phrase “decline of war,” and I only found a decline in one of them, and that was only at the end of the Cold War. Mostly, there’s just been no change over the past couple hundred years. And you could even argue that there’d been some evidence of increase in warfare prior to the end of the Cold War. So that’s number two.

Rob Wiblin: I guess the key scary finding is just that there’s not really any evidence that would make us feel confident that the threat that we face from war today is materially less than the threat that people have faced at many other times through history — times in which enormous, horrific wars broke out, and war was one of the most regularly destructive forces out there.

Bear Braumoeller: Correct.

Rob Wiblin: So we just shouldn’t be sanguine about the issue, I suppose is the bottom line. And what’s another key conclusion?

Bear Braumoeller: I think the third bottom line is that there is some hope. I don’t mean it to be an entirely negative conclusion. As you mentioned, patterns of international order I think are much better predictors of variation in international conflict than human progress over time. You don’t see a tonne of variation in conflict across the entire system over time. You do see variation across groups of states, and specifically across and within international orders — like the liberal international order, the Soviet communist order, the Concert of Europe, and so on.

So I think that in some ways I kind of do agree with people who argue that we’ve made progress. I think we’ve created something really impressive. Michael Howard wrote a book about international order where he referred to it as “the invention of peace.” So I think there is some hope if we can get a better handle on international order. The thing is we don’t really know how to use it. We don’t have a very good sense of how to optimise configurations of international order to create as much peace as possible.

Rob Wiblin: Fantastic.

The Enlightenment [00:16:47]

Rob Wiblin: OK so let’s park the data analysis in Only The Dead for now. Listeners can rest assured that we’re going to come back and discuss that in plenty of detail in an hour or so, as I have a lot of questions about its various strengths and weaknesses.

But for now let’s push on to a different issue that you cover in the book, which is the age of Enlightenment, and reason, pacifist values and humanism and so on, and what impact we might expect that to have had.

I’m really interested in this issue, because I think I probably had a strong preconception that the Enlightenment — and all of the intellectual advances that stemmed from that over the last 250 years — that that probably was pushing us towards a more reasonable world, in which conflict was less likely. That certainly would have been my assumption, coming in. I’ve changed my mind on that over the last few years, or at least I view it now as a lot less clear. And I feel like I had all the knowledge necessary to realise that that was a much less clear claim than what I thought it was.

So there are ways in which intellectual changes in the 17th and 18th centuries might push us towards peace, but there are also ways in which they might not — and in fact, did not. Can you lay out some of those?

Bear Braumoeller: Sure. The word “enlightenment” just has such positive connotations. It’s hard to think…

Rob Wiblin: “I became enlightened and then went to war.”

Bear Braumoeller: You tend to attribute all good things that came after the Enlightenment to some degree of enlightenment. But you’re exactly right that the Enlightenment gave rise to a lot of ideas, and some of those ideas made war more acceptable for new reasons that hadn’t existed before. Herder and nationalism, for example. Hegel and Marx on the value of a strong state. Justifications for uprising against monarchies, the invention of wars for peace in the Greek Civil War. Interventions in order to stop war. All of these are grounded, very firmly, in Enlightenment ideas. Everyone loves to talk about Emmanuel Kant, but Kant wasn’t the whole Enlightenment. So that’s one general point.

The other one is Enlightenment ideas, even when they have been sort of progressive and positive, have given rise to very illiberal reactions on the part of people who were dissatisfied with modernity. The recent waves of populist movements, for example, is a good illustration of that. These are fundamentally nationalistic, illiberal movements. So there are a couple of ways in which you can’t really draw a straight arrow from the Enlightenment to peace.

Rob Wiblin: Right. So yeah, this is a big, big shift in my thinking here. I was thinking about it: What is the Enlightenment? What is it fair to say is a consequence of the Enlightenment? Is it kind of unclear? It’s obviously a vague concept. It’s a difficult, undefined question.

Bear Braumoeller: Now, again, the caveat is I’m not an Enlightenment specialist, so take it with a grain of salt. But you know, you see much more of a fundamental reliance on reason as a vector to truth than revelation or faith. And it’s a fundamental reorientation of society. It had a tremendous, just incredibly pervasive impact, the more it spread. There were actually a variety of different enlightenments in different places at different times, but the overall trend was more toward a focus on better ways to truth. And you see that in the rise of universities, the rise of science, all sorts of different ways. But reason can lead you to some pretty dark places too.

Rob Wiblin: Yes. And even if it’s leading you in a good direction in the long term, it could be an extremely bloody path to get there, arguably.

Bear Braumoeller: Yes.

Rob Wiblin: So if you construe the Enlightenment that broadly — that it’s a turn towards reasoned argument as a way of assessing ideas and trying to arrive at truth — it’s almost easier to ask what in the present world isn’t influenced or isn’t caused by the Enlightenment than to say what is.

So obviously if anything is caused by the Enlightenment, surely the French Revolution qualifies. The French Revolution was not exactly super peaceful. Then you’ve got the anticolonial wars and various wars of independence fought by various different groups — the United States then Latin America, Haiti, then many other countries — that are not exactly super peaceful.

Then you’ve got communism. Definitely the revolutions were deadly. The wars fought by communist states to foster communism elsewhere were very deadly. Communism, good or bad, it was not necessarily a peaceful process. You’ve got all the antimonarchist wars, which was a massive ongoing turmoil in the 19th century, deciding how countries should be governed. Again, maybe antimonarchism was good, but it caused a lot of wars.

Arguably, the Enlightenment justified a whole lot of colonialism that otherwise people might not have been interested in. Of course, countries were engaged in colonialism for other reasons before, but the Enlightenment provided new possible intellectual ammunition that people could use to dominate other people claiming that they’re doing the right thing and supposedly using reason to justify that.

Then plausibly you could say all of the new weapons that we invented, maybe that’s caused by the Enlightenment in a sense — because science has, just as it’s enabled medicine, also enabled nuclear weapons. Then you’ve got nationalism. Now we already had nationalism, but there’s kind of new flavours, new styles of nationalism that are justified on Enlightenment grounds.

I think maybe the one thing you could say is that it’s a stretch to say, “I think that fascism or Nazism is a kind of enlightened” — of all of the modern ideas, it’s one of the least Enlightenment-influenced, but at least it’s a reaction against Enlightenment ideas, you could say. So it’s still, in a sense, a broader consequence.

So, wow. The Enlightenment has just caused so much, that to say that it has in general fostered pacifism and peace… I haven’t even mentioned, of course, now people have all kinds of ideas about humanitarian interventions and going to wars in order to protect people, in order to promote liberalism, in order to promote ideas that they think are good. If you put that to someone in 1400 — that they should go to war overseas in order to promote liberalism, or in order to protect people from being oppressed by their own government — that would’ve been regarded as ludicrous.

Bear Braumoeller: Right.

Rob Wiblin: OK, so that’s a very long rant, but suffice it to say it’s a complicated picture. I think maybe you could make a stronger case that democratic liberalism has tended towards pacifism and antiviolence. But again, it’s a complicated picture even there, although I might rate my chances more at making that case.

Bear Braumoeller: Yeah, and it also gets more complicated when you look into the relationship between parts and wholes. So certainly there have been arguments that liberal democracy is conducive to peace. One of the things that I find in a later chapter is that the Soviet communist order was also relatively peaceful under threat of force. So it was not exactly peace in the fullest sense, but it was the absence of conflict, right? And certainly the way that Lenin and Marx initially envisioned a communist state, peace would have been a big part of the goal. Lenin in particular argued that the Enlightenment led to liberalism, which led to capitalism, which led to imperialism, which was a major driver of war — and that communism was the solution to that. And you could make those arguments. But it turns out, when you put capitalism and communism in the same international system, that is not a recipe for peace.

So it’s complicated in many ways. In the book I discuss the Enlightenment a little bit. I don’t say much more than that. It’s a lot more complicated than this. You gave a fantastic recitation of all the different kinds of things that have followed from the Enlightenment, and I thought about how do you aggregate that into a big overall plus or minus? I don’t know. I have no idea. But it’s way more complicated than just, “We need more Enlightenment. We’ve got to double down on the Enlightenment.” On everything that came out of the Enlightenment? I don’t think you want to do that.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah, I want to make that joke: “Has the Enlightenment led to peace? It’s too soon to tell.”

Bear Braumoeller: Right, right.

Rob Wiblin: I followed really closely this pro-Enlightenment or uncertain-about-the-Enlightenment discourse. I imagine that a lot of what’s going on is people talking past one another. The Enlightenment is a very broad term. People mean different things. One group, the pro-Enlightenment group, is probably talking about a particular single strain of thought, or a class of thought, that has emerged from the Enlightenment among many others, and arguing that that style of reasoning leads to peace. And probably there they have a strong case.

Whereas the people who are against it are saying, “What about all these other things? What about colonialism and the reaction against that? What about communism and all of the wars that resulted from that?” If you consider it very broadly, then the effect is so broad, the question starts to seem almost silly in a way.

Bear Braumoeller: But there is sort of a cottage industry in big think history books, and people arguing that modernity is good, and modernity is bad, and we really were happier when we were hunter-gatherers, and so on and so forth. So it’s one of those things that people love to weigh in on. I envy them the ability to think broadly enough to put all those pieces together and come to an aggregate judgement.

Democratic peace theory [00:26:22]

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. Do you have a take on democratic peace theory? This idea that democracies tend to be very hesitant to get into conflict with another clear democracy?

Bear Braumoeller: Yes, a fairly complicated one. Well, first of all, there was no way that I could, as a scholar of international relations, live through the 1990s and not have an opinion about the democratic peace. We killed more trees with studies about the democratic peace in the 1990s than you can imagine. There’s strong evidence for it. There’s a fair amount of evidence that it’s strongest in the post–World War II period. And there just weren’t that many democracies before World War I, and they were pretty far apart, so you can see why it would be a little more difficult to say.

Rob Wiblin: Hard to tell, yeah.

Bear Braumoeller: But the post–World War II period is also the period when there was an ideological split, with democracies on one side and communist states on the other.

Rob Wiblin: So they were all within the same order.

Bear Braumoeller: Yes.

Rob Wiblin: So maybe that explains it, rather than democracy, per se.

Bear Braumoeller: Exactly. And Kant talked about what Bruce Russett has called the Kantian Triad — which is trade, shared institutions (for example, the international order), and democracy. And there’s a neat piece by one of my colleagues at OSU, Skyler Cranmer, along with two coauthors, Elizabeth Menninga and Peter Mucha, in PNAS in 2015. These folks are network folks, and they do a good job of dealing with the characteristics of the data. And they argue that the Kantian Triad as a whole does result in a reduction of conflict.

Rob Wiblin: Sorry, what’s the Kantian Triad?

Bear Braumoeller: Sorry. Trade, institutions, and democracy. Those three things. And they argue that those three things do produce peace, but that, of the three, democracy matters least, which is kind of an interesting finding. So the upshot is that, historically, democracy is embedded in larger historical structures — like networks of trade and international order. And it’s hard to divide up the impact of different variables in that sort of complex of things.

Rob Wiblin: Because they all tend to come together.

Bear Braumoeller: Yeah, exactly. And it’s not even clear that you should try to divide them up.

Rob Wiblin: Because they cause one another.

Bear Braumoeller: Yeah, exactly. They’re very interrelated, and as a complex, as a structure, we can say that they have this impact. And you can argue about what parts of it are most important, but there does seem to be a “there there.” That said, something that people often miss is that the Concert of Europe was a fundamentally conservative institution. This was a bunch of monarchs who had seen the French Revolution — they had seen liberty, equality, and brotherhood — and they wanted to stamp it out. “Forget it, we don’t want any more of that.” So that was a fundamentally antidemocratic international order, and it maintained peace for the better part of 50 years.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. I didn’t know what the Concert of Europe was until I read this book. So we’re going to get to that in a minute, and explain what it is in a bit more detail.

Is religion a key driver of war? [00:29:27]

Rob Wiblin: I can’t remember if you discussed this in the book, but I think a lot of people have the perception that religion is a key driver of war through history, and maybe still today. And perhaps that’s one thing that has influenced a lot of people to think that a more secular modern world ought to be more peaceful, and that’s one channel by which the Enlightenment has reduced war. Do you have any reaction to that idea?

Bear Braumoeller: Not a big one. Again, I can’t claim to have studied this systematically, and I don’t want to run roughshod over the findings of people who actually have. But I can say, at a broad level, that religion at other times has been a driver of peace. I just mentioned the Concert of Europe, which was a collection of the major powers in Europe. They got together, five major powers, and decided that they were going to cooperate to prevent revolution. Tsar Alexander of Russia very much saw this as a Christian organisation. He referred to it as the Holy Alliance. And there are all sorts of stories about the other people at the conferences sort of snickering behind his back and saying, “Sure, Alex, that’s fine.”

Rob Wiblin: “Whatever you say.”

Bear Braumoeller: “Whatever floats your boat. Just sign the paper.” But to him, Christian unity was sort of the motivation behind the Holy Alliance, which merged into the Concert of Europe. It became the Concert of Europe. And that was in part because if you were a believer in Christianity, you were a believer in the divine right of kings. And the divine right of kings is what the French Revolution was about. So the Concert of Europe was a repressive institution. It was designed to sort of roll back the clock, and then maintain the status quo. But it was, in some part, religious reasoning, and it maintained peace for quite some time. So it’s a complicated thing to answer.

Rob Wiblin: It’s a complicated picture. Yeah, absolutely. You can imagine both religion inspiring war between countries that have different religious views, and also promoting peace between countries that are neighbours, that have common religious values.

Bear Braumoeller: Right.

Rob Wiblin: So my substantially less informed opinion is just, I kind of scan through a list of all of the wars that I’m aware of in my mind. And I think, in how many of these was religion the key issue? Now, obviously, there were periods in history where religion was a key issue in most wars, the wars resulting from the Reformation, and so on. It’s very, very clear that religious issues are very central there. But in the modern era, there’s a lot of wars fought over issues that don’t really seem to be about religion. Or where religion is mentioned, but it seems like that’s a cover for other issues, at least arguably.

Bear Braumoeller: Yeah. There’s a wonderful book by Kalevi Holsti, written years ago. And I reproduced a graph from his findings, where it shows trends over time: religious wars are big in this period, and smaller in this period; and nationalist wars are small in this period, and rise up in the next one. That sort of ebb and flow is really fascinating.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. Now, we don’t fight over religion. We fight over the appropriate way to govern a country, the appropriate system of international order.

Bear Braumoeller: I don’t know if you’ve read a book called Nathaniel’s Nutmeg?

Rob Wiblin: No. I haven’t heard of it actually.

Bear Braumoeller: Really neat book about the discovery of the East Indies, and the race to obtain as much nutmeg as possible. And there were actually wars fought over the control of nutmeg, which they believed, at the time, cured the plague.

Rob Wiblin: Right. Wow.

Bear Braumoeller: So yeah, people fight over nutmeg. There’s a lot of things people fight over.

Rob Wiblin: Whoever controls the spice.

Bear Braumoeller: Yes, exactly.

International orders [00:33:07]

Rob Wiblin: OK, pushing on. The last third of the book is about international orders. You think changes in international orders seem to be one of the key drivers, the most plausible key driver, of changes in international rates of war initiation and escalation.

Bear Braumoeller: Right.

Rob Wiblin: Now, international order is a kind of complex concept that different people define a bit differently, but you put it as, “A multilateral security regime that involves one or more major powers, and that is legitimised by a set of principles that are potentially universal in scope.” We could stay on the abstract level, but I think it might be more useful just to talk about some different examples of international orders that people might be familiar with, and why they qualify as international orders.

Bear Braumoeller: So the Concert of Europe, which I’ve now been talking about for three answers in a row, I think, is a great example — because it involved multiple great powers, and the principles involved were taken to be universal, and they thought they had a fundamental understanding of the best way to govern the international system. So that’s a clear example. The Bismarckian system in Europe, in the 1870s and 1880s is a slightly less clear example, because Bismarck clearly believed that he had a good idea for how to manage Europe, and how to manage Germany’s security. It’s a little more arguable as to whether you could see that as potentially universal in scope, but err on the side of bringing it in, just to see what the results look like.

Rob Wiblin: What about some ones that people might have more context on? So what was the international order during the Cold War?

Bear Braumoeller: I think there were a few orders, and they were sort of nested within each other. So the Western liberal order, or the liberal international order, was what we think of as “the West” during the Cold War. The Soviet communist order is what we think of as “the East.” But I also think that there were a couple of other orders. The UN system is sort of an overarching international order that’s less binding, in a sense, and less — I don’t want to say less formalised; it’s extremely formalised — but less deep, in a security sense.

Rob Wiblin: Less strong, I suppose.

Bear Braumoeller: Yeah. And at the beginning, the great powers gave themselves a free pass by giving themselves a veto in the Security Council. So in that sense, it’s a limited international order. But also, I think especially after the Cuban Missile Crisis, there was an order between the superpowers — where they tried very hard to improve their ability to predict one another’s behaviour. I don’t talk about that order in the book — it’s more of a “this is my hunch” kind of thing than that I’ve got concrete data or historians’ accounts to back it up. But it does strike me that, if you take a look at the conflict management that the great powers engaged in, you could say that there was kind of a nascent major power order there. That’s what I mean by international order. So you’re right, it’s a broad concept.

Rob Wiblin: You talk about how there’s these different eras of international order. I suppose you could say, after the Cold War, there was a new one. And arguably, I suppose we’re entering into a new international order, with China being more assertive, and refusing to be constrained by the order that predominated in the year 2000, for example. Are there different “classes”? If you had to list “Here are the four different kinds of international order,” what would they be? Or is that the wrong way to think about it?

Bear Braumoeller: No, it’s fine. I mean, very broadly, I think the categorisation that makes most sense to me is: there are orders that are negotiated — the liberal international order would be a good example of a negotiated order among countries. There are orders that are imposed — like empires, where the subsidiary states don’t really have a choice, or the choices that they’re given are so unpalatable that they effectively don’t have a choice. And then there’s a third category that libertarians are particularly fond of: the spontaneous order — where interactions just spontaneously give rise to mutual expectations and rules of the road. So in a very broad sense, I think you can break orders down into those types.

Rob Wiblin: And is it fair to say that basically, the story with international orders is that once a bloc of countries has established an international order, internally, they tend to have substantially lower rates of violent conflict. However, if you have more than one international order on the scene at any one point in time, then their tendency to fight with one another is pretty substantial. And so, whether they’re good or bad, it’s kind of a balancing between these two things: that internally, they’re relatively peaceful, and externally, they can be quite aggressive.

Bear Braumoeller: Right. Yeah, exactly.

Rob Wiblin: That doesn’t comment on the anarchy situation, or the situation where there is no order. How does that perform?

Bear Braumoeller: Well, anarchy is, in a way, kind of the baseline condition. And it tends to be certainly more conflictual than life under international orders, and generally more conflictual than relationships across orders as well.

Rob Wiblin: Really? OK, so it’s really kind of the worst case.

Bear Braumoeller: It’s a really interesting question. So I wrote this book, and what I observed was higher rates of conflict initiation across international orders. I just sort of assumed what happens is you get two different groups forming, and once you have an in-group effect, you get a cross-group conflict. Well, it turns out that there’s a whole psych literature on this, and that doesn’t generally happen. In-group effect doesn’t automatically lead to out-group conflict.

So my lab and I came up with a model of how it is that hierarchy, and hierarchical order, and international war are related to each other. And we also found, in that model, that just the formation of multiple hierarchies, in and of itself, doesn’t cause an increase in conflict between them. So, it’s a really interesting puzzle of why it is you see increased rates of conflict initiation. And I’ve got a couple of answers that are potentially worth considering.

One is that multiple international orders don’t cause increased levels of conflict; increased levels of conflict cause multiple international orders. So the world becomes more dangerous, and as a response to that danger, you see international orders form. Which actually maps very well to the trajectory of the Western liberal order and the Soviet communist order after World War II. They fought on the same side, and only gradually did each realise that the other was a threat. And as that perception of threat increased more and more, there was an increasing tendency to try to form orders, to kind of counteract it. So that may be one reason that you see more conflict across multiple orders: that conflict creates orders.

Rob Wiblin: It’s reverse causation.

Bear Braumoeller: Yeah, exactly.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. I guess the technical term is that all of these things are endogenous. So it’s extremely hard to do causal attribution, because everything is causing everything else. Well, it plausibly is.

Bear Braumoeller: Well, that’s why theory is really important, right? Because unless you have a concrete theory of how these things happen, it’s very easy to convince yourself that shirtsleeve calculations or broad reasoning will lead you to the right answer. But we actually constructed a formal computational model to simulate international systems. And we fed it a set of premises, and we watched how the model behaved. And we came away saying, “OK, so why is there this conflict?” And we do see it happening, but we see it happening for exactly the opposite reason that we had thought.

Another possibility is that orders tend to increase ideological polarisation. When you say, “You can become a member of NATO, but you have to be a liberal democracy,” what that effectively does is it means that the process of forming an international order increases tensions between the member states and states outside the order, right? Because it increases the sort of ideological differences between the two, that can lead to war. So one possibility is that this process of making states more democratic, or more communist, draws them more into conflict with one another than they otherwise would’ve been.

So there are a couple possibilities for what this mechanism is, but we know surprisingly little, actually. And that’s one of the reasons that we’re doing this work, is to try to straighten this out.

The Concert of Europe [00:42:15]

Rob Wiblin: Yeah, fantastic. I learned so much from this last bit of the book. I mean, I know a bit about a decent number of different times in history, but it turned out that 19th century history was a much greater gap in my mind than what I had appreciated. I feel like it’s very natural that — like most people, I suppose — when I’ve looked into history, I’ve looked into World War II, then maybe the Cold War, then maybe World War I, then maybe you think about the modern era.

But at what point do you start studying the Bismarckian system? That seems like it’s perhaps more advanced than an amateur like me might typically get into. But I think it really would be helpful for people who are commenting on international relations, even in an amateur capacity like me, to have a broader reference class, a broader set of knowledge of different eras, and how countries got together in those times. Because having a tiny dataset of only four eras — especially four eras where the issues were often quite similar, and carried over between them — just means that you know very little. And you can plausibly just say things that will be very silly to someone who does understand the 18th century and 19th century, because there’ll be great counterexamples to what you’re saying.

Bear Braumoeller: Right. And actually, this is a general problem in studying international orders. There just haven’t been very many of them, right? So this is one of the things that I love about my research lab. The other members are graduate students, and you’ll be seeing their dissertations as books before too long, I hope, and I think they’re going to be really interesting.

They’re doing just incredible things, comparing the Syrian Empire to the Ottoman Empire. Or in another case, comparing the Concert of Europe with the formation of the United States, and saying, “Why is it that you get a unified state in the United States, but you don’t get a United States of Europe in 1815?” And they’re incredibly creative about how to come up with these comparisons, and incredibly fearless when it comes to diving into the literature on these places.

So it is a problem. Even if you go into the 19th century, you still have a pretty limited number of examples. I’m very lucky to be working with these smart, intellectually adventurous people, who are teaching me a lot about the Ming Empire. It’s really terrific.

Rob Wiblin: If there’s one thing you can say about history, it’s that there’s a lot of it. I think we need to stop producing it, until we can, preferably, deal with the history we already have.

Bear Braumoeller: Just have a pause. Yeah.

Rob Wiblin: The era that I was most keen to share a little bit about with the audience is this Concert of Europe period, where there was a very clear order that you’ve already discussed a little bit. To do a bit of setup here, in the late 18th century, you’ve got the French Revolution, a lot of new innovative and controversial ideas going around. Then you have the Napoleonic Wars, from around, was it 1800 to 1815? Incredibly bloody period. Napoleon never saw a country he didn’t want to invade. So there’s just been constant bloodshed. Finally, in 1815 or so, they managed to get rid of Napoleon, and they’re like, “All right, no more of this.” So just talk about the agreement that the European powers have put together at that point?

Bear Braumoeller: One of the reasons that Napoleon was so dangerous is that he kept running around Europe and saying, “You, Poles. You’re Poles. Be Poles. Be independent.” “You, Italians, you’re Italians.” They say, “Yes, we’re Italians,” and they’d rise up. So he became an enormous pain for these multiethnic empires that existed at the time. And if there was one thing that they could agree on at the end of the Napoleonic Wars, it’s that they were done with that; they’d had enough of this whole nationalist uprising thing.

And so they came together at the Congress of Vienna. And it’s interesting. There was a lot of negotiation, there was a lot of discussion, there were agreements made about the idea that they would work together to govern the European system, at least, and ensure that it would remain conservative and monarchical.

Even the UK was part of this, although Castlereagh was kind of out on a limb. Foreign ministers were not monitored with the same frequency that they are today, and he did a bit of freelancing. So there was this agreement, and partly because people knew that it wasn’t going to pass muster in Britain, it wasn’t formalised. And as a matter of fact, Castlereagh had to write a sort of strained paper in 1820, saying, “As you know, we will not be a part of any attempt to suppress democracy on the continent. Wink, wink.” So keeping the UK in was a bit of a challenge.

But interestingly, it was very thinly institutionalised. They met at a few congresses to discuss problems as they arose, but there was no central body. There was no UN building that they would go to, and meet on a regular basis. It was just a very ad hoc sort of thing. So I’m not surprised that people haven’t come across it, because it was very —

Rob Wiblin: Not so conspicuous.

Bear Braumoeller: Yeah. Now, it started after the Napoleonic Wars, as you mentioned. Interestingly enough, because it was so thinly institutionalised, it’s sort of hard to say exactly when it ended. It just kind of slowly faded away. But if you could point to one end point, I think it would be the Crimean War in the 1850s. But in that period, it was remarkably successful.

Rob Wiblin: In the book, actually, you say, “The four decades following the Napoleonic Wars were, by a significant margin, the most peaceful period on record in Europe.” Is that true, even considering the 1990 to 2020 period?

Bear Braumoeller: Sure. I mean, there was the war in Yugoslavia. Now, in part it was peaceful because anytime there was a threat to the peace, the great powers intervened. Sometimes bloodlessly, sometimes not. But I think, after a few interventions, people tended to get the message.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. Right. So it was like active peacekeeping, but it was effective. Why did it break down?

Bear Braumoeller: Largely because Russia, the UK, and France, having managed successfully to govern the international system for decades, stumbled into a war that none of them actually really wanted, in the Crimea.

Rob Wiblin: It’s one of those wars where people are like, “What were they doing? What were they thinking?”

Bear Braumoeller: Yeah, right, exactly. And I think it often wasn’t entirely clear to them. But it just made it very clear that you could no longer take consensus among the great powers for granted. And once that happens, you have Prussia saying, “Well, I do have some territorial ambitions that I’d like to realise, actually. And if nobody’s watching, if Mom and Dad are no longer punishing us for territorial aggrandisement, I have a few territories that I’d like to pick up.”

Rob Wiblin: Yeah, right. I guess it might seem a little bit odd to talk about this as a global international order. And obviously, it wasn’t.

Bear Braumoeller: No, no.

Rob Wiblin: It slightly is a confined set, because those major powers in Europe didn’t face external threats, really. So they could maintain peace between one another there. From their point of view, there were no wars being fought against them, or no wars that they weren’t choosing.

Bear Braumoeller: Right. Most orders are regional. Even the liberal international order is a regional international order.

Rob Wiblin: So what can we learn from that period that could possibly be relevant today?

Bear Braumoeller: It’s an idiosyncratic period. And most of these countries were ruled by individual people, or small numbers of people. So it’s kind of difficult to apply the lessons. But we can say, I think, that it showed us that major powers can prioritise international peace over domestic ideology. There were substantial differences, and growing differences, in domestic ideology over this period. But for a time, at least, they managed to subsume those differences, and actually pursue joint interests in peace.

Rob Wiblin: I see.

Bear Braumoeller: The other thing is, Michael Howard — Sir Michael Howard, you’ve got to give him his due — refers to the Concert of Europe as “the invention of peace.” And his argument — and I’m not going to argue with a historian of his calibre — is that this was the first international order in which the maintenance of peace was an explicit objective. And so, in that way, it’s a watershed event in the international system.

Rob Wiblin: Was it unusual to have a treaty between so many different major powers, where they all agreed to try to avoid fighting one another? This wasn’t typical?

Bear Braumoeller: Yes, that’s right. As a matter of fact, there was a discussion after the end of the Cold War about the possibility of a major power concert of some sort. That idea was floated a couple of times. And the problem was, I think a lot of people looked at the Western liberal order — or the liberal international order, as they were calling it by that point — and said, “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”

Rob Wiblin: I see. Yeah. Possibly we could live to regret that decision.

Bear Braumoeller: Yes. Yeah, we could.

Rob Wiblin: Do you think that the main reason for people taking this novel approach was just that they were so scarred by the Napoleonic Wars — and I suppose also internal revolutions within lots of countries — that they were willing to set aside their territorial ambitions, and their interest in invading one another, and say, “We’ll leave that for another day, or maybe never, and let’s just focus on not getting overthrown?”

Bear Braumoeller: Right. Yes. And I think, in part, that’s wrapped up in the theories of war that they had in mind. So the major power conflicts that had occurred previously had often been limited in scale, certainly relative to the Napoleonic Wars. They’d involved professional armies. The Napoleonic Wars were really a revolution in warfare. And I think there was an uncommon unity. Just about all the powers were affected in one way or another, so there was an uncommon degree of leaders being on the same page about what the problem was — which was revolution — and how big the problem was, which was: revolution anywhere threatens the peace everywhere.

If you’ve just had a big war, you may overcompensate and think that wars are going to pop up all over the place. International order, I think, benefits from that perception. It’s one of the reasons you see international orders form after large wars. People say, “I don’t want to do that again.” But the fact that this order was able to form, despite everybody not quite being on the same page about principles of international governance, is kind of inspiring. And I think the historians who wrote about “Do we need a new Concert?” saw that as inspiring as well.

The Bismarckian system [00:53:43]

Rob Wiblin: Later on in the 19th century, possibly going into the early 20th century, Europe followed a different system, that was also reasonably peaceful, called the Bismarckian system. What were the characteristics of that one?

Bear Braumoeller: Bismarck was a really special case. He designed a system of alliances — actually three systems of alliances — in order to deter conflict. He did this because conflict would almost inevitably involve Germany. Germany had just won a series of wars and declared itself a unified German state. And in the process, it had made basically a permanent enemy out of France. Anybody who attacked Germany from the east could count on France attacking from the west.

So Bismarck had very good reasons for becoming a man of peace in 1871. He basically used alliances to tie up the other great powers and prevent coalitions from forming, in particular coalitions involving France. He did this, like I said, in three different clusters of alliances, over the course of about 20 years. Most statesmen, I think, and certainly not his successors, couldn’t manage that balancing act.

Rob Wiblin: I see. The idea was that he would ensure that there was never a coalition or an alliance large enough that it would think that it was a good idea to launch a war because they would be able to win and gain territory. Things would always be sufficiently finally balanced that everyone would be too nervous to actually start a war.

Bear Braumoeller: Correct.

Rob Wiblin: OK. Do you think he got lucky?

Bear Braumoeller: It’s a great question. It’s very common to attribute the Bismarckian system to sheer diplomatic genius. I don’t think I’ve seen substantial movement away from that interpretation, although I’m not exactly steeped in the literature on Bismarck. But he may have been fortunate in that the countries that were closest to him, for the most part, had just lost to Germany.

Rob Wiblin: They also saw the virtues of peace.

Bear Braumoeller: Exactly. But the big caveat to that is France really wanted to retake the territory that it had lost.

Rob Wiblin: Is there any potential relevance to us today from that system? It seems like it’s a little bit more of an anarchic one than perhaps what we have right now. But nonetheless, you can balance powers off against one another and keep them quiet that way.

Bear Braumoeller: Yeah. It’s funny. The people who refer to themselves as political realists, people like Henry Kissinger, have been aspiring to be Bismarck for generations. There are definitely people around in the foreign policy establishment who have ideas about how it is that you can align politics in such a way as to reach peace.

Now, often it’s impractical. I’ll give you an example. Henry Kissinger argued that the best way to avoid war with Ukraine and Russia was for Ukraine to declare neutrality. He’s probably right. That probably would’ve worked, but the Ukrainians weren’t going to do that.

Rob Wiblin: They didn’t want to.

Bear Braumoeller: It’s not going to happen. You know?

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. I’ll just throw in here that one of the most important points that you make — throughout the book, actually — is that we could choose peace. We could have peace, if only we didn’t care about the issues at stake enough to be willing to fight. If we’re willing to surrender and give up those things, then we don’t have to fight. But however, people have always cared about some things, or at least sometimes have cared about some things, more than peace. That remains true today. That’s why we’re willing to fight. That’s why we might be willing to fight a massive war, because there might be something incredibly important to us at stake.

Bear Braumoeller: That’s right. I quote John Lennon on this, who, during the Vietnam War, had a wonderful song called “War Is Over.” People would ask him, “How do we end the war in Vietnam?” He said, “Just stop fighting. Put your guns down and walk away.” Now, Lennon was not exactly the cheerful Beatle. I’m pretty sure that what he had in mind when he wrote that was, “You could stop war, but I know you’re not going to. And that’s because there are things that you care about more than peace.”

Rob Wiblin: Yeah, it’s true. It’s a quote that could, from one point of view, seem incredibly naive, and from another point of view, could seem incredibly smart. “You’re choosing to do this because you care about other things as well as peace.”

Bear Braumoeller: Yes, exactly.

Rob Wiblin: It’s always an active choice.

The current international order [00:58:16]

Rob Wiblin: OK, let’s talk now about what recommendations might possibly come out of your research. Of course, all of these issues are pretty tentative. It sounds like the international order research project is at an early stage and potentially has a long way to run. Fingers crossed there’s a lot more to learn.

First up, there’s a reason why we’ve done a lot of interviews this year on war. It’s very much in people’s minds these days. Firstly, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and more recently, a lot of sabre-rattling over Taiwan. Looking around, what characteristics of the current international order stand out to you as important and salient?

Bear Braumoeller: I think the way to describe it is that we have a fairly well-defined order in the liberal international order. There are a couple of smaller regional orders. Russia, I think, is the easiest one to point to. The Russians for a long time have believed that the countries in the “near abroad” — that is, the former Soviet states — are only really nominally independent: they’re independent by the good graces of Moscow. With the exception of the Baltics, I think, which were obtained later, and I think that Russians don’t see themselves as being that —

Rob Wiblin: Invested in it.

Bear Braumoeller: Yeah, exactly. But the other former states of the former Soviet Union, I think that Russia has been spending part of the post–Cold War period essentially reestablishing its political dominance in those areas. A big part of what’s happened is that we’ve run out of wiggle room. We’ve run out of empty space. The liberal international order has expanded to the point where we’re now talking about incorporating former Soviet states. That’s a point at which international orders bump up against each other.

Rob Wiblin: Push comes to shove.

Bear Braumoeller: Yeah, exactly.

Rob Wiblin: How about China?

Bear Braumoeller: It’s funny. There was a statement early on in the Ukraine War from, I think, the Chinese foreign ministry. It started off by saying, “People are drawing these parallels between Ukraine and Taiwan, and they’re completely unwarranted. The situations are completely different.” I thought, “Great. That’s terrific. I’d love to believe that.” Then the statement went on to say, “Because Ukraine is an independent country, whereas Taiwan is actually part of China.”

Rob Wiblin: I’m reassured.

Bear Braumoeller: Yeah, exactly. I’m just like, “Oh, that’s so much better. Yeah, you’re right. That’s awesome.”

Rob Wiblin: The one that shouldn’t be at war is at war, and the one that should be isn’t yet, I guess.

Bear Braumoeller: Yeah. Part of what’s going on here is that the stakes are abstract and not really easily divisible. If Russia and Ukraine were fighting over Crimea, and only Crimea, that’s something that could be resolved fairly easily. What they’re fighting over is what international environment they want to live in. Russia wants to live in one in which the former Soviet states are subservient, and Ukraine is not interested in living in that world. And you can’t really split the pie.

That’s a problem with Taiwan as well, and possibly even a more serious problem. Because the war in Ukraine has gone on for a while. Sometimes you’ll see people saying, “My guess is the way that this is going to end is that Russia de facto swallows part of eastern Ukraine and they declare peace and call it a day.” I could conceivably see that happening just because of the prevalence of Russian speakers in the eastern part of the country. I don’t see any of the same dividing lines in Taiwan. Russia invading and doing really poorly militarily did not increase Ukraine’s willingness to give up part of its country. I’m not saying this is an obvious or easy deal to be made, but I don’t even see that in Taiwan.

Rob Wiblin: Are you saying it’s quite hard to reach a peaceful negotiated settlement between Ukraine and Russia? Like one of the reasons why you ended up with a war was that the issues at stake are so expansive that these countries are going to have with one another — about the entire international culture — that you couldn’t simply sit down and make an easy agreement with various different points, because everything is on the table?

Bear Braumoeller: Right.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. Interesting. Are there any other important aspects of the international order that we haven’t mentioned that are worth discussing? We haven’t really discussed Latin America or Africa or Southeast Asia very much, but I suppose potentially, from a great power war and nuclear war point of view, they’re not the most important actors.

Bear Braumoeller: I think the thing that I would say is, when people talk about things that can be done to increase the prospects for peace in the current international structure, there are a handful of ways to think about it.

Let’s start with an understanding of war that comes from Clausewitz — but actually was really well articulated by a guy named Jim Fearon in 1995 — called the “bargaining theory of war.” He pointed out that, yes, war is an extension of politics — but in the sense that you have an issue, you negotiate over it, and war is what happens when you can’t reach a negotiated settlement. So we need to understand why you can’t reach a settlement.

From that perspective, what you’re seeing in these cases is that issues arise that people are willing to fight and die over, and they can’t arrive at a settlement short of war. How do you fix that? You can make them less committed to the values that they currently have. Ukraine could say, “I don’t really want that territory.” That’s not likely going to happen. One in which the likely costs of war are very high here —

Rob Wiblin: Is nuclear deterrence?

Bear Braumoeller: I was going to say one theoretical way to do this would be to give Ukraine nuclear weapons. Do you want to do that? No. I don’t want to do that. I think it’s a terrible idea. It might increase the odds that the war will end, but if it doesn’t, it’ll probably increase the costs dramatically.

But actually, I think that the unbelievably broad, crippling sanctions that were implemented in Ukraine are a fantastic signal for China, and a warning for China that they can expect the same in Taiwan. I think actions like that actually can make a difference. It’s hard to make a difference in the current conflict, but it can make a difference for the future.

Rob Wiblin: By setting an example that you’re willing to pay a high price in order to punish territorial conquest or annexation.

Bear Braumoeller: Right. Exactly.

Rob Wiblin: OK. I’m not quite sure what the practical implication is. I suppose things are going on in the world all the time, and I want to have some opinion. Ideally, I want to say, “It would improve humanity’s prospects if country X does Y.” Then I’m trying to bring this international order framework to bear and then think, “What does this imply about policy for the UK or the US? In principle, what would I want Russia to do?” It seems like one bottom line with the international order framing is that the most peaceful state of the world would be one hegemon who is powerful enough to either dominate or ideologically sway everyone in the world, so now there’s peace within this one order and then there’s no one else to fight — I guess, unless aliens come along.

Bear Braumoeller: Or, less uncharitably, provide security for everybody.

Rob Wiblin: I see.

Bear Braumoeller: Because one way to think about it —

Rob Wiblin: If you fight amongst yourselves, we will punish the aggressor.

Bear Braumoeller: Yes, exactly. I think that’s a common understanding of how hierarchical international orders form: that it’s a trade of security for autonomy.

Rob Wiblin: I see.

Bear Braumoeller: The smaller states say, “We’ll give you some policy thing that you want. We’ll vote with you at the UN. We’ll give you basing rights. We’ll pay cash, whatever — and you will provide security for us.” If there’s a hegemon that’s powerful enough to make that trade with all the countries in the world, then that would definitely be a situation in which you’d find more peace. We are pretty powerful, but we’ve decided to limit the scope of our security deals to democracies. That inherently limits the scope of the order.

Rob Wiblin: Is that for ideological reasons or just because it’s so impractical to try to make those deals with everyone? The US military is powerful, but it’s not omni-powerful.

Bear Braumoeller: I don’t know. I think they’d rise to the challenge. We already outspend the next 14 countries — or whatever it is, 11 or 12.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah, but you’ve got to ship everything over. It’s a whole effort.

Bear Braumoeller: Right. No, I think, actually, it’s because that would mean agreeing to outcomes that are normatively unacceptable. We would have to be cool with the way the Chinese treat the Uyghurs, or at least agree to look the other way.

Rob Wiblin: Sorry, in what way?

Bear Braumoeller: If we were to include China in a broader sort of concert system.

Rob Wiblin: I see. Right. And we feel uncomfortable because we’re making allies out of people we have ideological and moral disagreements with.

Bear Braumoeller: Right. Exactly. Again, this gets back to the John Lennon point. The simple answer to how to stop war is stop caring about things, which…

Rob Wiblin: It’s a great example of ways in which the Enlightenment doesn’t universally encourage peace. Without the Enlightenment, we might not give two shits about a group of people we know nothing about, on the other side of the world. We might not care about the conquest of Taiwan and the rights of Taiwanese people. That would be bad in one way, but it would be good in the way that you’d be less likely to have a great power conflict over those issues.

Bear Braumoeller: Right. Exactly. Steven Pinker talks about the rise of empathy as a cause of peace. And it probably is, but it also leads us to go fight wars in faraway places for people we empathise with.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. I want to ask a question about what kind of policy suggestion you might have about how the liberal international order ought to shift itself over time, or how it ought to interface with China. What agreement might it ideally make with China or Russia?

Bear Braumoeller: Yeah, sure. How do we get from our current understanding of international order to a more peaceful system? One way, as I just mentioned, is to care less about things. But that’s just not going to happen.

Rob Wiblin: It’s not going to happen. Yeah.

Bear Braumoeller: Another is to increase the likely costs of war, so the states are more reluctant to go to war.

Rob Wiblin: But that’s a pretty double-edged sword.

Bear Braumoeller: Yeah. As I say, the way that I’m trying to do it is to say, “Hey, escalation is really bad. Escalation is probably more costly than you realise.” I’m trying to get that message out there. If you’re trying to predict how old a person is going to be, the older they are, the fewer years you give them. With a war, it’s exactly the opposite. The bigger it gets, the bigger you predict it’s going to be. People don’t get that intuition. I’m hoping that helping to get that to sink in will at least help people appreciate the costs of war that they already face.

Rob Wiblin: I see. Something that’s unambiguously bad is if people are taking actions that incur a high risk of a really catastrophic war and they don’t realise it. Because then you bear all the costs of the war, and you don’t have any of the benefit of deterrence.

Bear Braumoeller: Right.

Rob Wiblin: I see. I think one problem we face is that we haven’t had a massive war in a long time. So people do not appreciate it. They don’t read the news about Ukraine and imagine New York being a smouldering ruin, and fully contemplate that actions that they take regarding Ukraine could result in the complete destruction of their societies — in a way that for people in 1946, that was probably very front-of-mind.

Bear Braumoeller: Right. They also don’t appreciate things like the Iran–Iraq War, which is not a war on a global scale, but it was a massively costly war for those two societies. Unbelievably deadly. Even if they don’t see the potential for the spread of war across the international system, they should appreciate the possibility that a war that’s reasonably well contained is going to kill a lot of people.

Rob Wiblin: Right. I see. Just making it more salient to people, that even in the present day, wars escalate to a phenomenal degree and kill a shocking fraction of the population of the combatant countries. We should remember that, because it could be us next. Are there any incremental changes to the current international order that would lower the risk of war, that are actually plausible?

Bear Braumoeller: Right. Like I said, I think the most hope lies in information — information about the dangers of escalation, information about other states’ likely costs of war. This is why I think sanctions were such a good thing, because they conveyed information to China that the likely costs of invading Taiwan are probably higher than they think. I think there’s room to work at the margin there. There’s also room to work by increasing the costs of invasion, which we do by bolstering the troops in the area and so on and so forth. I think there is some wiggle room there, but in terms of something large and transformational that’s going to produce a change like the end of the Cold War, it’s hard to imagine that without a fundamental restructuring of international order.

Rob Wiblin: Do you think there is a case for a more transactional — arguably, “accepting of evil” — arrangement between the US and China, that would say, “The war is just so costly that we have to sacrifice other values”? To some extent, you already are. The US did not invade China because of the Uyghurs. It complained a whole bunch, but it knows that that is not anywhere near within its power. We are transactional in some ways. We just don’t call it that.

Bear Braumoeller: One of my students, Andy Goodhart, is actually looking at this question. Not the China question in particular, but he’s looking at international orders that have based their legitimacy primarily on performance. Like, “We will keep you from being invaded,” rather than legitimacy in the sense of, “We have a normatively correct way of ordering society, and we think you agree with us. So let’s form an international society based on those principles.”

I think China, to a large extent, is already doing this. If you ask people in China, “Why do you support the Chinese state?”, they’re not like, “I’m a true believer in communism.” I think a lot of the answers you would get are, “My parents grew up in a hut and now I drive a BMW.” I tend to think, at least domestically, China already sort of operates on those principles. I’m not entirely sure.

It’s a huge, big, open, interesting question as to whether we can reach an accommodation along those lines. But the problem is you have to convince people to restructure what they would say is the most successful alliance in history.

Rob Wiblin: Also going half of the way there could be the worst of all worlds. Because let’s say you start giving more transactional signals to China that you’re not really going to have a values-based foreign policy. And then they invade Taiwan. Then your population’s not actually with you, and maybe your heart wasn’t really in that in the first place. So now you do respond. Now, you’re at war, because you’ve given indications that you’re not going to retaliate. But, actually, you always were, in your heart of hearts. It’s just a nightmare.

Bear Braumoeller: Yeah. These kinds of international relations are full of perverse outcomes like that.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. So lots of people in the audience would love to help reduce the risk of both smaller wars and larger wars, if they can. What could listeners take away about ways that they could potentially contribute, or that their countries could contribute?

Bear Braumoeller: I’d suggest graduate school in political science for one thing.

Rob Wiblin: Honestly, it does feel like that’s the answer sometimes, that maybe one has to be extremely knowledgeable in order to give good advice on these things.

Bear Braumoeller: Yeah. The way that we’ve structured our pursuit of understanding war is not one that maps really well to understanding the relationship between order and war. Academia, I think, needs a fundamental reorientation in terms of how it thinks about conflict and aggregation across levels and dynamics and things like that. This is where the book gets pretty dark. I think the best thing that people can do is think about that card analogy — 96 cards, do you really want to draw one — and try to get a better fundamental understanding of how escalation works, and then vote accordingly. Because I think if I had understood just how dangerous war is, prior to writing this book, I would’ve been a lot less evenhanded in policy arguments in the past 20 years or so. I would’ve seen the maintenance of peace as a much higher priority. I think that that can help.

Rob Wiblin: It seems like making a blockbuster movie about a war between the US and China, that occurs in a realistic way where both sides get absolutely screwed, and at the end of the movie these countries are in shambles. Hopefully, it’s watched on both sides, and it really makes salient to both sides the risk that they’re running, and maybe causes both to be a bit less aggressive and try to find more ways to avoid it. It’s a little bit harder to see how that backfires.

Bear Braumoeller: That’s a good point. I don’t know if you remember a movie called The Day After?

Rob Wiblin: Yes. Horrific.

Bear Braumoeller: It really brought home the dangers of nuclear war. You could tell, for a while at least, it had that impact on society. It was all anybody talked about. If I remember correctly, it was even before social media, and it was clear that everybody was talking about it everywhere.

The Better Angels of Our Nature [01:17:30]

Rob Wiblin: OK that’s all my questions on international orders. Let’s now come back to the core topic of the book about which we left everyone hanging earlier on, which is the empirical question of whether, by the numbers, war is in long-term decline or not.

So as you mentioned earlier, the book is in part a response to The Better Angels of Our Nature by Steven Pinker, where among other things he argues that indeed war is in long-term decline. On balance, obviously you think that when it comes to interstate conflict, Pinker is wrong to think that that kind of violence has a long-term trend downwards, and we should be less worried about it today than maybe we should have been 50, 100, 150, 200 years ago.

But before we dive into that, what do you think Pinker gets right? Because he makes many arguments in The Better Angels of Our Nature and you’re far from disagreeing with him on everything.

Bear Braumoeller: No, I don’t [disagree with him on everything]. And I think it’s sort of interesting. I think he gets the broader story about human cooperation right, despite not getting the particulars.