Transcript

Cold open [00:00:00]

James Smith: Mirror bacteria might be able to persist in the environment directly. So they might be able to grow in soil or in oceans. It could be like living on Earth today without an immune system, or even like living on Earth today with an immune system, but where you could catch Ebola from trees or from your pet cat. To cause harm, all a mirror bacterium needs to be able to do is grow.

How much would it cost to make mirror life from where we are today? People estimate something like 500 million to a billion dollars would be sufficient. That motivates the need to have these discussions now.

I think at the moment, the marginal impact of an extra person working on mirror life is huge. You could probably become the expert in policy around mirror life in your country within a few weeks or months.

Who’s James Smith? [00:00:49]

Luisa Rodriguez: Today I’m speaking with James Smith. James is the [director] of the Mirror Biology Dialogues Fund and an adjunct associate professor at J. Craig Venter Institute. James was also one of the authors of the bombshell Science paper that drew attention to the risks of mirror life last December.

Thanks for coming on the podcast, James.

James Smith: It’s great to be here. Thanks for having me.

Why is mirror life so dangerous? [00:01:12]

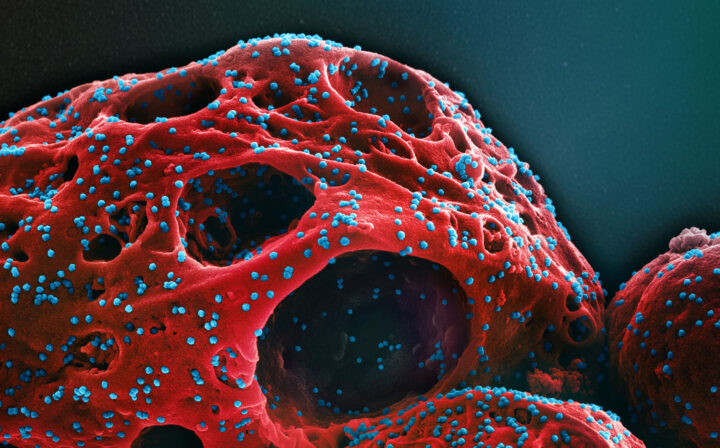

Luisa Rodriguez: So in the Science paper, you and your coauthors basically make the argument that we’re reasonably close to creating what’s called “mirror life.” Mirror life is basically like normal life, but the molecules are arranged backwards, in the mirror image. And despite this seeming like actually quite a trivial difference, it makes these life forms, which could be bacteria, extremely dangerous to not just humans, but most species — including animals and plants. What exactly makes them so dangerous?

James Smith: Yeah, it might seem like a trivial difference, but actually this is a really fundamental break from normal biology. Ever since the last universal common ancestor 4 billion years ago of all life on Earth, all of our DNA has always been made up of right-handed building blocks — meaning that it makes double helix that twist to the right. And mirror bacteria would have the opposite: they’d have DNA that twists to the left. So introducing it to Earth would be a bit like introducing an alien invasive species that nothing on Earth has evolved to deal with.

To take one specific example, our immune systems need to be able to recognise pathogens when they get into the blood to be able to mount an effective response. The way that it does that is through receptors that you could think of like gloves. Now, putting a right hand into a right-handed glove: it fits well, it activates the immune system. But if you try and put a left hand into a right-handed glove, it doesn’t work properly. Mirror life would be a bit like that. A lot of the interactions that are so fundamental to biology are not going to work in the same way.

Luisa Rodriguez: Yeah, it’s wild. It just doesn’t seem intuitively like this should matter. It’s the same molecule or the same life form. But because there are all of these mechanisms that most of us never think about where the hand has to fit inside the glove, actually it’s really important. Is there more we should talk about in terms of what mirror life actually is?

James Smith: Yeah. Mirror life would be a type of artificial life that you’d make in the lab. A mirror bacterium is what we’re mostly going to talk about today, because that would be the simplest form of life that you’d make. And it would literally have exactly the same components as a normal bacterium — it would have DNA, proteins, ribosomes, a membrane — but all of those will be made in their mirror image form.

Luisa Rodriguez: And you think that this problem is kind of on par with some of the most pressing global problems we know of — like AI safety and other biosecurity threats. Why is this comparable? I think a thing that’s surprising is that it feels very new. This paper was quite recent. It feels quite surprising that we’ve discovered a new kind of science that happens to be one of the most threatening things to humanity and the Earth.

James Smith: People have actually posited the existence of mirror life since the 1800s, so it’s not a completely new thing. People have mentioned the risks of it kind of in passing in the literature, but it wasn’t until last year that anyone looked into this properly. And this is the worst biothreat that I’ve seen described. I think it can be on par with AI safety for some people, depending on your skill set.

That’s driven a lot by the fact that there are literally probably 10 people working full-time to think about the risks of mirror bacteria and what could be done to address them. So it’s incredibly neglected.

I also think it’s really tractable. We’re used to thinking about technologies like artificial intelligence or nuclear, where you have massive risks but also potentially massive benefits. And mirror life seems to be an exception to that: the benefits that we can foresee are really quite minor, whereas we have these massive risks. And I don’t think there are going to be strong commercial drivers to want to make mirror life. That means I think we have a really good chance at kind of cutting off this risk.

Luisa Rodriguez: To make this a bit more concrete and kind of drive home the importance of this issue: you’ve been trying to raise the alarm about it, but imagine that you fail, and your worries about what would happen if mirror life were created and released into the environment came true. How would that play out? What would it look like?

James Smith: Obviously, this is skipping a lot of nuance, but it could be like living on Earth today without an immune system — or even like living on Earth today with an immune system, but where you could catch Ebola from trees, or from your pet cat, or from a carrot that you eat or something like that. So it could be really crazy.

More concretely, I’d break it down into two areas of risk: one is immunological, and the second is ecological.

Mirror bacteria could infect not just humans, but a wide range of different species, because they have this property of broad immune evasion. We’re used to thinking about something like COVID or influenza that can spread from human to human, but it doesn’t also infect plants and insects and livestock — whereas mirror bacteria might be able to do that.

And the second area is around the ecological risks. Mirror bacteria could grow and might be able to persist in the environment directly; they might be able to grow in soil or in oceans — and that opens up another transmission route, directly from the environment to multicellular hosts. So you might be able to get infected by mirror bacteria from dust blowing into your home that has bacteria on it that you inhale or something like that. And we don’t really have the tools and technologies to deal with a threat like that at the moment.

Luisa Rodriguez: Just to make sure I understand: when you say “living without an immune system,” that is really importantly different to living with a normal immune system, but encountering a new pathogen that we haven’t seen before.

So COVID is an example where we’re exposed to new versions of pathogens all the time, but our immune system is able to figure out some kind of response that allows us to, for the most part, defeat those kinds of infections. In the case of mirror life, is there an analogy to understand how exactly it’s different from that? How it’s not that: it’s living without any immune system at all?

James Smith: I mean, there might still be parts of the immune system that work, but there are examples of people who have had immune disorders that essentially replicate what it would be like to not have an immune system.

There was, for example, a guy in the ’70s called David Vetter, who was also known as Bubble Boy. When he was born, he had to be immediately put into a sterile plastic chamber, where he lived all 12 years of his life. All of his food, any of the toys that he used, anything like that, before entering that plastic chamber, needed to be sterilised. So there’s a proof of concept that we could live in a world like that, but I don’t think it’s a world that we should be aiming for.

Luisa Rodriguez: Yeah, that is horrific. It’s not that we have to kind of learn the specific immune response that’s going to work for this particular pathogen. It’s that most likely we are fundamentally not going to be able to. So in this case, this person, Bubble Boy, lived in this environment for the duration of his life because his immune system was never going to figure out how to tolerate bacteria and respond to them effectively. And that is what mirror life would be like, because our immune system would be just completely ill-equipped to dealing with it.

James Smith: Yeah, that sounds about right. There’s a lot of nuance here that we’re going to unpack. But I think this is a reasonable analogy. And we know from a lot of people who have defects in just one major pathway of immunity that they’re similarly really susceptible to bacterial infections. So even if one or even many parts of the immune system do work, that’s not enough to be confident that you’re going to be protected from an infection.

Luisa Rodriguez: OK, I want to get into that. But first, why would anyone make mirror bacteria, given that there’s massive downside — and we’ll talk in a bit about the nuance about this — but not much upside?

James Smith: I mean, historically, I think the main reason people wanted to do this was because it would be a really cool technical project. I think there is something aesthetically very pleasing about creating this mirror of life on Earth that I completely buy into.

But I don’t think it’s sufficient justification when there are these risks. People didn’t know about these risks until quite recently, so now I don’t think any well-meaning scientist is going to go ahead and build mirror life. In fact, all the people who previously said they wanted to make mirror life have been part of this discussion and are calling for mirror life to not be made. So what I’m most concerned about now is malicious actors that might in the long term want to make this to cause a huge amount of harm.

Also, the possibility that AI could do this. This is something that’s been recognised in a fair amount of AI commentary now — like in AI 2027, they talk about mirror bacteria in the slowdown scenario; Will MacAskill talks about this in his “Preparing for the intelligence explosion“; and a bunch of other senior AI scientists have been referencing this work. So that’s something that I think needs more thought.

It’s also possible that someone might develop mirror bacteria for industrial applications, but at this stage I think that’s quite unlikely.

Luisa Rodriguez: How close are we? My understanding is that we can’t make mirror bacteria yet, but we’re making progress toward it. Does that mean it’s like a year away or is it decades away?

James Smith: If you ask the synthetic biologists, most of them who work on this will say something like 10 to 30 years away. But I don’t think that’s really pricing in the potential for transformative AI to speed things up significantly. Another way to think about this is how much would it cost to make mirror life from where we are today? There people estimate something like $500 million to $1 billion would be sufficient, and that could make it happen much more quickly. And there are people like George Church who think this might happen literally in the next couple of years.

So there’s a lot of diversity here. I think it’s really hard to be confident in any particular estimate — and I think that motivates the need to have these discussions now about what we should do to address the risk.

Luisa Rodriguez: How did you end up involved in this work? My sense is that you were already doing work to reduce biological risks in the world, but not involved in this work, something like over a year ago.

James Smith: I got involved in this middle of last year. Before that I was working on AI-enabled biology, doing some little bits on AI safety, and actually thinking that I would work on AI safety in the longer term. But within two weeks of hearing about this issue, I quit the other work I was doing to focus full-time on this, and have been doing that ever since.

The main reasons for that were the tractability and neglectedness in combination with the scale of this problem. When I first got involved in the project, I worked with John Glass and Jack Szostak, two leading, really top scientists, to coordinate this working group of scientists and write the paper that brought this risk to the attention of the world.

Luisa Rodriguez: OK. And my sense is that this is especially true among the scientists who really wanted to make mirror life because it was super cool, but that in general it’s been true that when scientists first hear about this, there’s at least some scepticism that mirror life will be as catastrophic as you’ve just laid out. Did you have any of that scepticism, and was there anything in particular that convinced you?

James Smith: Yeah, I was definitely sceptical initially. I think pretty much everyone who first hears about this is. I think that’s understandable. Like, base rate, some crazy science thing that people say is risky, it’s going to end the world: it’s probably not.

But the difference here is the amount of work that went into really thinking through this in detail. I think two things really convinced me.

One was the fact that some of the best scientists in the world — some of the best immunologists, ecologists, synthetic biologists, but also biosecurity experts and others — had been looking into this, specifically being asked, “What’s the problem with the analysis? Where is there a hole in this? How can we rule out this catastrophic risk?” And they hadn’t been able to. That I found pretty compelling.

Then the other thing was just imagining what it would actually be like to live in a world where mirror bacteria existed if this analysis was right: any exposure to the outside world could end up being fatal, you could catch it from plants, whole ecosystems could be destroyed. That kind of blew my mind, and I thought this is something I need to get involved in.

Luisa Rodriguez: Yeah, I think the thing that really struck me was that these are some of the most accomplished scientists of our time. It’s people who have made extremely groundbreaking discoveries. It’s not like random scientists that we haven’t heard of and they don’t work on anything. So super mind blowing.

James Smith: Yeah, it was pretty wild and is pretty wild to get to work with all these amazing people.

Mirror life and the human immune system [00:15:40]

Luisa Rodriguez: Let’s talk more about what makes mirror bacteria, and mirror life more broadly, potentially so catastrophic.

So when a normal bacteria enters the body, it wants kind of what any organism wants: it wants to survive and reproduce, so eat and kind of double itself continuously. And in normal human bodies, for most people, the immune system responds by mounting a counterattack with white blood cells and the whole immunity thing. What happens when mirror life enter the body?

James Smith: We’re used to thinking about the immune system as being able to deal with any arbitrary threat that’s thrown at it. And that’s kind of the case for most things that actually do get thrown at it. But the difference with mirror life is that we haven’t evolved to be able to deal with mirror life. Much of the immune system depends on specific binding between molecules that need to have a certain shape — and with mirror life, the molecules that matter are going to be reversed, so a lot of this binding isn’t going to work.

To take an example: in the innate immune system, which is the first line of defence that the immune system has, for that to be activated, you have these things called “pattern recognition receptors,” which basically bind to molecules on invading bacteria. And those molecules on the invading bacteria are chiral. Examples would be bacterial DNA or flagellin, which is a protein in the bacterial tail.

In mirror bacteria, those would be reversed, so they wouldn’t bind properly to the pattern recognition receptors. That means that the innate immune system wouldn’t be activated properly. That’s important because the immune system is actually highly interdependent. Ruslan Medzhitov, who was one of the coauthors on the Science paper, discovered that the adaptive immune system, which mounts your antibody response, depends on the innate immune system to work. So just breaking this one part can kind of break the whole immune system.

But with mirror bacteria, it wouldn’t just be breaking this one part. There are other parts that we think wouldn’t work too. There are lots of analogies from humans and mice that we can look at to sort of see how that plays out in experiments.

Luisa Rodriguez: Cool. Just to make sure I understand, the innate immune system kind of recognises foreign things like bacteria by having, like… I guess a lock and key feels like a very common analogy. So it’s got a lock with a certain shape, and a normal bacteria has like a tail that fits in that shape. And then when they come together, the immune system is like, “It’s you! I recognise you. I’m going to mount an attack because I know that you give me illness.” But the mirror bacteria has kind of the mirror-image tail and it just doesn’t fit.

James Smith: What you described is the way that chirality is important in general across a lot of biological interactions.

I think the best analogy is probably a hand in a glove. So if you think about an immune receptor as a glove, let’s say it’s a right-handed glove. Right-handed gloves fit right hands very well. And the pathogen’s molecules, let’s say they’re the right hands. If instead you’re trying to put a left hand into a right-handed glove, it’s not going to go in properly. Maybe it will go in a bit, which might actually be the case with some of this, but it’s not going to fit as well.

That’s kind of the fundamental issue: the immune system isn’t binary, so just one part of the immune system working is not necessarily going to be enough. And we know from human immune disorders that if one important part of the immune system breaks, then people will die in childhood. For MHC class II deficiency, patients that have this disease usually die before the age of 10. About 40% of them die [correction: it’s actually closer to 75%] before the age of 10 unless they can get a curative bone marrow transplant. And that’s just one part of the immune system not working. With a mirror bacteria infection, that part is very unlikely to work, I think.

But also in the adaptive immune system, the pattern recognition receptor binding is unlikely to work. And again, there are disorders that mimic that. There’s a disorder called MyD88 deficiency, which basically means that the pattern recognition receptor repertoire doesn’t function properly. And in patients that have that, something like 30% of them die before the age of two.

Luisa Rodriguez: Oh god. OK.

James Smith: So it’s quite bleak.

Luisa Rodriguez: Horrible analogies to keep in mind. How do these diseases of the immune system, and mirror bacteria in theory, cause humans to die?

James Smith: We don’t know for sure. It’s pretty hard to know, because we haven’t ever seen anything that’s exactly like this. But one way to think about it is kind of like weeds taking over a garden. They’re not deliberately causing harm, but they’re just growing and spreading and using up nutrients. And eventually, if something is growing and spreading in your body, it’s going to cause an issue.

One way that might play out is with something that looks like sepsis. Sepsis is a common cause of death for if you have a bacterial infection. It’s actually the third most common cause of death in the US once you’re in the hospital. So it’s pretty common, but it’s also not that well understood.

But basically, if you have mirror bacteria in your blood, they’re going to be replicating, using up nutrients. And eventually, those nutrients would have been used by your host cells for something. There’s a reason that they’re there. That’s going to eventually start to cause some of your host cells — let’s say in one of your organs, like your liver or something — to start to die.

And your immune system is pretty amazing. It can detect foreign things, but it can also detect when your own cells, when their insides are outside of them. So that would start to happen: these cells are dying, and they’re releasing their insides out into the body, and that causes an immune response. But when people have bacterial infections that are quite severe, that immune response often gets out of control and starts a positive feedback cycle where the immune system overreacts and that ultimately causes people to die.

Luisa Rodriguez: Wow. The irony of that. The immune system is like, “I’m going to help!” and then actually it’s extremely unhelpful.

James Smith: Yeah, it’s pretty unfortunate. Another way that it might happen is, if they got to extremely high concentrations — which would probably not usually happen with something other than mirror bacteria — it might physically start to block things, or result in there not being enough oxygen in the blood for you to survive. So there could be some really unusual pathologies.

Luisa Rodriguez: A thing that I find kind of strange about this is it just feels really counterintuitive that mirror bacteria could have this catastrophic effect on the human body, but the human body is kind of powerless and defenceless against mirror bacteria. Why is there this asymmetry? Is there some intuitive way of understanding that?

James Smith: It is quite counterintuitive, but it just happens that when you get into the details of what’s going on, it seems to be true. One way to think about it is: to cause harm, all a mirror bacterium needs to be able to do is grow. And we can be pretty confident that it would be able to grow, because we know that there are enough achiral nutrients in the body — so ones that don’t come into mirror image forms. And as long as it can grow, it’s ultimately going to cause harm.

Whereas for a human immune system to be able to respond to a mirror bacterium effectively, it needs to be able to recognise that it’s there, and the processes by which it recognises the mirror bacterium are likely to fail.

Luisa Rodriguez: I guess if you think about what a mirror bacteria’s goals would be — eating, reproducing — for reproducing, it seems like there’d be no issues there. I can imagine a mirror bacteria needs to consume chiral mirror image nutrients. To what extent would that be a barrier to mirror bacteria infections getting really out of control?

James Smith: Yeah, the first question I had when I heard about mirror life was, “I don’t get it. What would it eat?” I think this is a question that a lot of people have, actually.

A lot of nutrients do come in left- and right-handed forms, but not all of them. Some of them are achiral. An example of an achiral object is a sphere: you reflect it in a mirror, and it looks exactly the same. And if you think about the “hand into a glove” analogy, this would be more like a hand holding a ball: the ball kind of looks the same regardless of which hand you are. And nutrients can be like that too. In human blood you have things like acetate, acetoacetate, glycerol, succinate, pyruvate: all of these are achiral nutrients that are present in quantities that it looks like would be enough to support growth.

It turns out that there’s really interesting experimental evidence from E. coli — natural chirality E. coli, just normal E. coli, a type of bacterium that’s very commonly studied — that you can grow it on completely achiral carbon sources as food. So you can basically feed it only achiral food sources, and it will still grow.

Luisa Rodriguez: I see. OK.

James Smith: From the perspective of a mirror bacterium, an achiral food source looks exactly the same as it does from the perspective of a normal chirality E. coli, so you can just directly infer that the mirror bacterium would be able to grow on the same things. And then we know that those achiral nutrients that E. coli have been shown to be able to grow on are present in human blood at concentrations that would be sufficient to enable growth.

There is some uncertainty here. They’re going to have some fitness disadvantage: they’re going to probably grow a bit more slowly than they might otherwise.

But this is assuming that we’re just taking an exact mirror of a natural E. coli. The thing I’m most worried about is a malicious actor doing this. In that case, if you’re trying to cause harm, you would engineer into that bacterium the ability to consume common chiral nutrients, like glucose, and you would no longer have this nutritional constraint.

I think it’s pretty hard to get out of the conclusion that if someone was trying to cause harm, they would be able to engineer around some of these constraints. There’s already a blueprint for how you would introduce the ability to consume d-glucose, which is the common form of glucose. There’s an Alphaproteobacteria that can metabolise mirror glucose, so there’s one that we already know about in the world that can metabolise mirror glucose. You could use that pathway, but in its mirror form, and engineer that into your mirror bacterium. Then it would be able to consume normal glucose, and that’s a very common nutrient.

Something we haven’t talked about is if you were to make mirror bacteria for industrial applications, you probably also would want to engineer them so that they could consume common nutrients, because those nutrients are going to be easier to get hold of to grow it. So let’s say you were making mirror bacteria to produce drugs, which is one thing that people have been interested in: you’d probably want to engineer the bacterium to be able to consume glucose, and that means that the risk of an accident there would be high.

Luisa Rodriguez: Yep. Makes sense. Bad news all around.

Nonhuman animals will also be at risk [00:28:25]

Luisa Rodriguez: Is there an intuitive way to understand innate and adaptive parts of the immune system? I feel like an intuitive analogy might help me keep it straight as we talk about this more.

Is “innate” something like, over many centuries and much longer, our bodies have evolved the ability to recognise certain bacteria or other organisms that have been around for a long time? And “adaptive” is something like we notice new things in the environment that we haven’t been exposed to before, and we figure out a way to then mount an immune response to those new things, even though we haven’t evolved specific lock-and-key mechanisms for those particular pathogens? I’m basically guessing based on the words “innate” and “adaptive.”

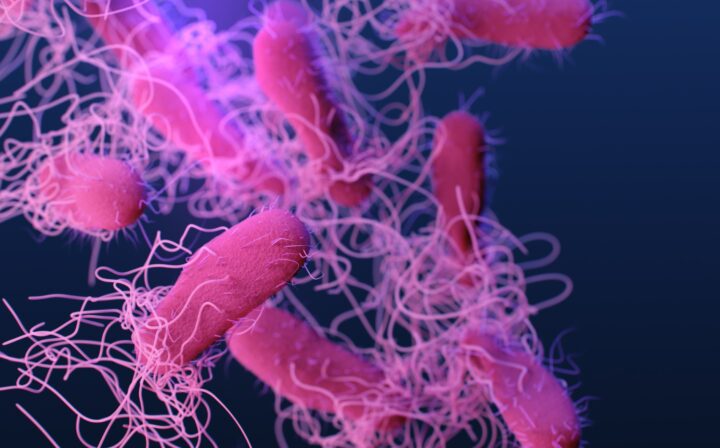

James Smith: Yeah, that’s pretty much right. So the innate immune system, one way to think about it is the first line of defence. It works by recognising patterns that are common to pathogens. For example, it recognises bacterial DNA, and all bacteria have bacterial DNA. It recognises lipopolysaccharide, which is really common on the surface of bacteria.

Adaptive immunity is kind of a specialised defence. In theory, it can mount a response to any arbitrary invader. So you have antibodies that have so much diversity that they can basically bind to any potential surface — including, actually, to mirror proteins. Some of the key cells in adaptive immunity to be aware of are T cells and B cells.

Luisa Rodriguez: Let’s turn to animals and plants and ecosystems more broadly. What would mirror life do when a nonhuman animal is exposed to it?

James Smith: Most vertebrates have immune systems that are quite similar to human immune systems. So the last common ancestor of the vast majority of vertebrates that are alive today had an innate immune system that has the characteristics that we talked about — with pattern recognition receptors that play a key role, and had adaptive immunity based on T and B cells.

So that means that the deficiencies that we’re expecting in humans are likely to be applicable to a lot of other animals as well. But there is diversity in animals, so I don’t think this is universally going to be the case. Some of them will have different susceptibility.

The Atlantic cod, for example, has lost the ability to present antigens via MHC class II and instead has an expanded set of these pattern recognition receptors. And the zebrafish, which is a really commonly studied model organism for developmental biology, has 10 times the number of NOD-like receptors, which are a type of pattern recognition receptor, than humans and mice. And most of these receptors are not characterised, so we don’t know what they bind to. They might bind to achiral things.

More generally, I think it’s very likely that some animal immune systems will just happen to work against this. Having said that, I still think it’s plausible that a large fraction of animals could be susceptible here. There are even some vertebrates, like lampreys and hagfish — which, if you’ve never seen a picture of them, they look really like the sandworm from Dune — and they have slightly different immune systems which we haven’t looked into in as much detail, but share the same principles. That’s vertebrates.

Then in invertebrates, so things like insects, the immune systems are less well characterised. So insect immune systems are less well understood than vertebrate ones, but we do know that insects have innate immunity that’s quite similar to what we have in vertebrates. They lack an adaptive immune system, but they do have innate immune systems that similarly rely on pattern recognition receptors to get them to work.

Fruit flies are one of the most well-studied examples, and their antibacterial defences being activated is downstream of binding of a pattern recognition receptor to a molecule called peptidoglycan, which is a chiral molecule that’s present in bacterial cell walls. And there have been experiments where these fruit flies have that receptor knocked out so it doesn’t work, and that really increases the susceptibility of the fruit flies to infection by bacteria: common bacteria that don’t normally cause disease will end up killing them.

This is also true in mosquitoes and bees. Beyond that, I’m not so sure. There’s a lot of this that hasn’t been studied in detail, but the same principles of immunity are common to all animals, so I think we should unfortunately be quite worried.

Luisa Rodriguez: Yeah, grim.

James Smith: I’m somewhat confident that there’ll be at least something that would be able to respond to this. But in the animals that we’ve studied the best — humans — we do know enough to be quite worried. Even in humans, there’s definitely a possibility that we’re missing something in the analysis, and in fact the immune system can deal with it in some unpredictable way. It’s going to be very difficult to rule that out.

But many of the world’s best immunologists have looked into this and have been unable to rule out this scenario where it causes harm to humans. These are people like Ruslan Medzhitov, who discovered the fact that the adaptive immune system depends on activation of the innate immune system; Mark Davis, who discovered T-cell receptors; David Relman, who was the first person to characterise the human microbiome — huge names in the field have looked into this and decided to coauthor this paper, calling attention to the risks. And they haven’t been able to find a knockdown argument for why we shouldn’t be concerned.

Will plants be susceptible to mirror bacteria? [00:34:57]

Luisa Rodriguez: And how about plants? I can imagine there being a similar story, but I can also imagine plant immune systems being very different to animal ones.

James Smith: Yeah, plant immune systems are actually conceptually quite similar to animal ones. They don’t have adaptive immunity, but they have innate immunity, similar to insects. And that innate immunity similarly has these pattern recognition receptors that detect common patterns on bacteria.

To give a specific example, plant leaves have little holes in them called stomata. The leaf surface has these pattern recognition receptors that will bind to common patterns on bacteria. When they do that, the stomata will close up in something called stomatal defence to stop the bacteria from being able to get into the leaf. That probably wouldn’t work as well with a mirror bacterial infection, so the bacteria might be able to enter the leaf through the stomata.

Once it’s inside the leaf, you have this space in between cells called the apoplast, and the cells around that space again have these pattern recognition receptors on their surface that let them detect bacteria getting into the leaf. If they detect them, then they mount a response, releasing things like reactive oxygen species. Again, that might not work as well.

But a key difference between plants and animals is that plants rely a lot more on physical barriers for defence, and mirror bacteria by default would lack the specialised enzymes to break down parts of the plant which might be necessary for it to move between leaves or to get into the plant vasculature. So mirror bacteria might not be able to get into the xylem or the phloem, which are like the veins of the plant, and then move around it.

So it’s kind of unclear whether it will end up causing serious harm to plants. I think there’s a reasonable chance that it would, but plant immune systems generally are much less well understood. Again, some of the top people have looked into this — Jonathan Jones, who discovered a lot of parts of plant immunity, is one of the coauthors on the paper — but I think there is more uncertainty here than in the case of animals.

Luisa Rodriguez: So the thing that seems promising for plants is, whereas animals have more of this lock-and-key function, plants have more like brute forcing brick walls. And mirror bacteria, the fact that they’re this other shape doesn’t make them better able to get around that. They just also might struggle getting around the brick wall.

James Smith: Yeah, that’s right. It’s still possible that they would, to be clear. So mirror bacteria could end up being able to kill lots of plants, including crops. I think we are going to struggle to rule that out.

One way that this might happen is that a common way that bacteria get into the phloem, which is one [part] of the veins in plants, is through phloem-feeding insects. The insects have the bacteria in their salivary glands, and then they’re feeding on the phloem — which will have sap in it, which is kind of the blood equivalent in plants — and then the bacteria get from the insect into the phloem. That could happen if you’re having insects that have been infected with mirror bacteria.

Luisa Rodriguez: OK, yeah. God, I can see how there’s so much uncertainty. Because there are some reasons to be optimistic in all of these different cases, maybe in some cases more than others, but I would not have thought of how insects that are infected because they do have similar immune systems to other vertebrates could then get around the brick wall, and that’s how plants are infected. It’s a bit of a minefield, isn’t it?

James Smith: Yeah. It was kind of surprising to me initially how common these features of immunity are across all different multicellular life. I think the thing is that no multicellular life has had a reason to evolve to be able to deal with mirror life, because it’s never interacted with it. So in a way, it makes sense that this would be an evolutionary blindspot for it. There’s no reason why it should be able to detect it. But I think a lot of people initially have an intuition that the immune system is just really good at dealing with any arbitrary threat. In fact, it seems like that wouldn’t be the case here.

Mirror bacteria’s effect on ecosystems [00:39:34]

Luisa Rodriguez: Can you explain the broader environmental risks?

James Smith: Yeah, definitely. Mirror bacteria could really damage a lot of habitats, drive potentially a lot of multicellular species to extinction, and might even change things like geochemical cycling.

We’ve talked about the immune system defects, so there’s the direct impact on animals that could of course impact ecosystems. But mirror bacteria would also escape common forms of predation. Normal bacteria are killed by viruses all the time. There’s about 10 times the number of bacteriophages, which are viruses for bacteria, than there are bacteria in the world. So these are literally everywhere, and they would not be able to infect mirror bacteria.

The reason is that mirror bacteria wouldn’t be able to read the genetic code of the viruses. The way that viruses replicate, they don’t have their own machinery —

Luisa Rodriguez: Oh right, I forgot this about viruses! Sorry, continue.

James Smith: Exactly. They don’t have their own machinery to be able to replicate. They have to use the host cell’s machinery. So firstly, they’d probably struggle to even bind to the surface of the mirror bacterium. But let’s say they could, and they inject their genetic material into the mirror bacterium. That genetic material won’t be read by the host cell. So the ribosome in the mirror bacterium won’t translate any RNA into proteins, or that transcription of the DNA won’t work. They would be completely immune to this. And this is something we can be very confident in. It’s basically 100%.

Luisa Rodriguez: Oh my god. Whoa.

James Smith: Yeah. Why that’s important is because this is a really common source of death for bacteria. If they aren’t going to be subject to this, they’re getting a massive fitness advantage, and that means they might actually be able to spread in the environment and outcompete other bacterial species as well. So they might be able to grow in soil, or they might be able to grow in the oceans — as well as infecting all of these different species that we talked about already.

Luisa Rodriguez: OK, so that’s viruses and bacteriophage. Are there any predators that would be able to successfully harm mirror bacteria?

James Smith: So we can be very confident that the bacteriophage won’t work. There are a bunch of other predators that normally eat up bacteria too. These include amoebae, or protists, which basically work like macrophages in the immune system. They engulf their prey, and many mechanisms in that process of engulfing prey and then killing it depend on interactions that probably wouldn’t work with mirror bacteria.

Luisa Rodriguez: Of course they do.

James Smith: Classic, right? So I think a lot of protists are unlikely to want to consume mirror bacteria. Even if they could, it’s not clear they’re going to get much nutritional value from them — so they might actually evolve away from them rather than towards wanting to do this in the first instance. So major sources of predation, including infection by viruses, but also consumption by protists or amoebae, are probably not going to happen.

Luisa Rodriguez: OK. I guess in vertebrates, our lifespans mean that we evolve very slowly. Given that some of these predators probably have much, much shorter lifespans and reproduce much more frequently, should we expect some of them to evolve to be able to consume mirror bacteria? Especially given that it sounds like mirror bacteria could become very abundant in the environment because of this fitness advantage?

James Smith: I think eventually, yes, that would happen.

Luisa Rodriguez: But it would still take a long time?

James Smith: It would probably still take a long time. Bacteriophage are effectively never going to evolve to be able to do this because they’d have to switch their whole genetic code around, and that’s a massive evolutionary step.

But other predators like protists could eventually evolve to do this. I think it’s actually more likely. And I should say this is an area where the dynamics would be so complex that it’s difficult to reason confidently about it. But I think we can make some guesses. Protists initially might actually evolve to not want to consume mirror bacteria when they’re only present at low concentrations in the environment, because they’re probably not going to get much nutritional value from them initially.

So the first few protists that accidentally eat up mirror bacteria, the mirror bacteria might end up being toxic to the protist, and so then you’d be creating evolutionary pressure not to eat them. Once mirror bacteria got to a relatively high concentration in the environment, then there would start to be evolutionary pressure for things to eat it — but that means mirror bacteria are already present at quite a high concentration.

And I think something that’s important to underscore is that I don’t think that mirror bacteria are going to take over the whole world and outcompete all other species. They only need to be present in the environment at a relatively low level in order to cause these massive risks. So you inhale about a million bacteria per day, and even if 1% of those were mirror bacteria, you’d be inhaling 10,000 mirror bacteria per day. One percent is about the prevalence of some of the more common bacteria that we have in the environment, so it’s not crazy to imagine a bacterial species getting to that, but it really doesn’t need them to be 100% of all bacteria for these risks to be the case.

Luisa Rodriguez: OK. Another thing that you mentioned was changing the environmental nutrient cycles. Do you mean things like the nitrogen cycle? The carbon cycle? And if that’s right, how would that work?

James Smith: To be clear, I’m less worried about this scenario because I think it would play out over a much longer time period, so we’d have more time to deal with it. But there are still pretty interesting scenarios to get into.

We’ve mostly been imagining a mirror of something like an E. coli, which needs to eat food to grow. And that food is often chiral, so that gives some limitation on its growth. But there are bacteria that don’t require any food to grow. Marine cyanobacteria are an example here. These fix carbon directly from sunlight, and they can grow with just achiral nutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus, sulphur, that sort of thing.

One of the very common causes of death for these marine cyanobacteria is infection by phage: up to 50% of marine cyanobacteria die from phage infection. So if you introduced a mirror cyanobacterium, it would have basically these huge advantages, because it wouldn’t be able to be infected by phage, but potentially have none of the limitations on nutrient availability. So the population of marine mirror cyanobacteria might grow to be very large.

If they’re going to be very large and nothing is eating them because they don’t really give any nutritional value to the protists that usually consume them, then they might start to sink to the bottom of the ocean and fix more carbon. Now, it’s really unclear what would end up being limiting here, so I’m not confident at all in what would happen. But it could be the case that they act as a massive carbon sink, taking a lot of CO2 out of the atmosphere.

Luisa Rodriguez: Yeah, OK. And initially we might be like, great, we have too much carbon in the atmosphere. But how far could it go? And what would the implications be if it went beyond helping us with climate change a bit?

James Smith: To me, it seems really difficult to kind of titrate the amount of CO2 that you’d be able to take out of the atmosphere in this way, because once you had this population of mirror cyanobacteria growing, they would be really difficult to control and they would start to evolve into other things.

You might think, couldn’t we just control them with mirror phages that we make or something like that? But at that stage, there’ll already be a lot of them around, it’ll be impossible to drive the population to zero, so we might just overshoot by miles and end up in an ice age or something like that. Equally, that might not happen and we might end up killing loads of trees through mirror bacteria and releasing loads of carbon into the atmosphere. So depending on the mirror bacterium that’s being made, it could go in different directions.

Luisa Rodriguez: OK. So we have mirror bacteria. I guess in the scenario that we’ve mostly been talking about, it’s deliberately made and released by probably malicious actors, but I guess it could be accidental by industry if they’ve been using mirror bacteria for some beneficial scientific purpose.

It seems like that would be one or two or a handful of species. How quickly would we expect these species to properly colonise the globe? Maybe it’s not like they’re not as common as the most common bacteria, but how long will it take for them to be everywhere?

James Smith: It’s hard to be confident, but we can look at some existing diseases and how quickly they’ve been able to spread as examples. COVID, because people spread it through air travel, was on all inhabited continents within four months of the first case.

More generally, the speed at which a pathogen is going to spread is dependent on how quickly the fastest-moving host moves around. So if humans are being infected, it’s very likely going to be humans. But insects can also spread diseases very quickly. Myxomatosis, which is a virus that infects rabbits, is spread by fleas and mosquitoes, and that was spread in the 1950s around Europe at a rate of about 7,000 kilometres per year. The circumference of the Earth is about 40,000 kilometres, for context.

So even if humans weren’t infected, which we expect they would be, this could still travel quite quickly. But even if it’s travelling relatively slowly, it’s going to be almost impossible to eradicate. It seems like once you’ve introduced it, it’s pretty much irreversible.

Luisa Rodriguez: Yeah. I guess the thing that really strikes me about this is… I think when I originally heard about mirror bacteria, I was kind of imagining something like all of the mirror life out competes the kind of analogous life and some other life forms, and then we kind of end up with this weird alternate universe with mirror everything.

But it’s not that. It’s like mirror bacteria or whatever mirror life ends up being released outcompetes a bunch of other species and infects and kills a bunch of other species — ranging from plants, other bacteria, nonhuman animals and humans. And we don’t get mirror giraffes. Maybe this is a really trivial point, but we just end up in a world with mirror bacteria and the random few species that had some natural immunity. And then it stays like that until evolution works over millennia to advance some life forms in some way.

Which is just like the definition of catastrophic. I don’t know why that wasn’t the immediately obvious implication to me, but it’s just really, really bad. It’s really bad.

James Smith: Yeah, it definitely is quite a bleak picture.

How close are we to making mirror bacteria? [00:52:16]

Luisa Rodriguez: I’m interested in coming back to the feasibility of making mirror life or mirror bacteria specifically. You’ve already kind of alluded to some of the reasons why at least malicious actors in particular might want to build and release mirror life. But can you talk more about: can we do this yet? Who can do it? How far away are we from doing it? And maybe just a bit more on why different groups of people might be interested in doing this, given how horrific the implications sound?

James Smith: So ways that it could happen: someone could invest a lot of money into it. For example, in industry, if they wanted to develop this to make mirror molecules, which I really don’t think would be worthwhile or good, to be clear, but it’s something we could imagine happening.

A malicious actor might want to do this if they’re trying to cause a huge amount of harm.

And then a rogue AI might want to do this if they were trying to kill a huge number of people, so people in the AI community are taking this seriously as a threat that could be accelerated by AI. I think it’s likely that transformative AI could accelerate the development of mirror bacteria. But it’s worth noting that the steps to go from where we are today to making mirror bacteria are quite wet lab-intensive. They’re all trial-and-error kinds of projects. So I think autonomous scientific AI agents might be helpful here, but I don’t think design is a key constraint — and I think that is an area where AI might be most helpful, so actually, relative to other biothreats, we might get less uplift on the development of mirror bacteria. But it still could accelerate it.

Luisa Rodriguez: OK, we can’t make mirror bacteria yet. How difficult is it going to be, concretely? You’ve said it might be 10 to 30 years away, I guess two George Church thinks, which is insane and very upsetting, but what are the steps? And which steps do we know how to do and which steps do we not know how to do?

James Smith: The most likely way that I think we would make mirror bacteria is through something called the bottom-up pathway, which basically means taking all of the mirror components and then putting them together and booting up life.

There are two relevant research fields here. One is mirror biochemistry, which means making the mirror components; one is synthetic cells of natural chirality, because that gives you the method to boot the cell or to make life. You need advances in both of these to be able to make mirror life.

On the mirror biochemistry side, one of the key milestones that we haven’t yet achieved is a mirror ribosome. The ribosome is the most complicated molecule in the cell. It’s made up of 54 proteins and in bacteria, three big RNA molecules that all have to bind together in a really precise way in order to work. And no one has yet made that.

The reason why making mirror components is so hard is because the way we do this normally in natural chirality is we use life to help us make things. We don’t have that. So we have to make everything through chemistry, so it’s much more difficult to do it. So there are big advances needed on the mirror biochemistry side of things.

On the synthetic cell side of things, no one has yet taken completely artificial dead components and put them together to make life. Once you can do that, then you have a proof of principle and a method that you could apply on the mirror.

But there have been really quite amazing breakthroughs on both sides that we could go into.

Luisa Rodriguez: Yeah, let’s go through some of those. Maybe let’s start with the synthetic biology side.

James Smith: So synthetic biology is a huge field. Synthetic cells is a subset of that, and then mirror life is like a tiny, tiny subset of that.

So with synthetic cells, some of the most impressive breakthroughs have been from John Glass and Craig Venter, who are two really impressive synthetic biologists that people will probably be familiar with, and who were both on the Science paper.

In 2010 they, for the first time ever, basically took a completely dead genome that they made from bottles of nucleotides — from bottles of As, Cs, Gs, and Ts — and they transplanted that dead genome into a living cell, and then took the genome that was originally in there out of that cell. And the genome was of a slightly different species, so they kind of converted a bacterium from one species to another.

Luisa Rodriguez: That is wild! That’s actually super, super wild.

James Smith: Yeah, it’s crazy. I think the relevance to mirror life is it shows you in principle that you can take a completely dead genome and use that to make life. So you’re going from a chemically synthesised, completely dead genome, putting it in a cell, and then that genome is then the only thing in the cell after a certain amount of time that’s being transcribed and translated. So it’s pretty amazing.

And then in 2016, they basically did a really similar experiment where they created what they call a minimal cell. The idea here is they’re trying to remove all of the nonessential genes from the genome. And again, they’re doing this with a dead genome they make from the bottles of As, Cs, Gs, and Ts, and removing as many genes as possible from that genome and then transplanting it in. Mycoplasma is the simplest bacterium that we know of. It has a genome that’s about a million base pairs. They managed to halve the size of the genome.

So this is an example of the most engineered bacterium that we have. We understand what a lot of the genes do, whereas in most bacteria we really don’t. One of the interesting things about the minimal bacterium is that it’s quite feeble, because a lot of the genes that they removed are needed for being able to deal with being in different environments and things like that.

Luisa Rodriguez: So technically it is then alive, but it’s not its best self.

James Smith: Yeah, it’s definitely alive. It can do stuff in the lab. But people, when they think of really highly engineered life, often think of something like this minimal cell. So when they’re thinking about mirror life, they imagine that it would be something like that — but actually it wouldn’t necessarily; it could be a mirror of an already robust bacterium like E. coli.

Luisa Rodriguez: Yeah, that does seem important. OK, so that’s synthetic cell biology. Talk about some of the advances from this other field, mirror biochemistry.

James Smith: The central dogma is the hardest part of the cell to recreate, and is also the one that you know you would need to be able to make a mirror cell. The central dogma is all of the machinery needed to transcribe and then translate DNA into RNA and then to proteins. And people have been working on basically trying to create that in mirror image form.

The part they haven’t been able to do yet is the ribosome, which is the most difficult part of that, but they have been able to do other parts of it. So people have made DNA polymerases, which replicate DNA, so that’s a key part of this. They’ve also made RNA polymerases which transcribe DNA into RNA in mirror form. They’ve made the RNA polymerase in mirror form and then taken mirror DNA that’s made synthetically and transcribed that into [mirror] RNA.

So it’s pretty amazing. And all of these have to be made using chemistry, not through life. So they’re making these really complicated molecules using chemistry, and using clever tricks to kind of stitch them together and get them to work.

Using that RNA polymerase, people have been able to make the ribosomal RNA, which by weight is 70% of the ribosome. So although we can’t make the full mirror ribosome yet —

Luisa Rodriguez: Making a good chunk of it.

James Smith: Yeah, we are able to make a good chunk of it. And the really difficult thing left to do is put all of the parts of the mirror ribosome together correctly. In principle, we can already make proteins that are big enough to make a whole ribosome. So we would be able to make all 54 proteins that you need, if we tried hard enough, probably. But putting them together in the right order — such that they fold properly, interact properly, and then will be able to translate RNA into proteins — is really difficult, and not something that people have done yet.

Luisa Rodriguez: So if you are trying to make mirror bacteria, do you need to make every part, or can you make these parts that describe and then transcribe and then cause molecules to be created in the mirror form? I guess I’m asking because it seems extremely hard.

If we get really simple, if we imagine creating a human body that was the mirror form somehow, you could either create every organ and Frankenstein it that way; or maybe in theory, you could make a genome that means that all of the mirror cells are created, which makes all the organs mirrored or something like that. Does that make sense?

James Smith: Yeah, it does make sense, and it’s a really good question. Because a bacterium has loads of stuff in it — it has loads of proteins, loads of things in its membrane — it’s just very complicated. We don’t know for sure what you need to boot up a cell, but it might be the case that all you need is basically the central dogma plus a genome encapsulated in a membrane, as long as you can get the central dogma to read the genome.

So it might be the case that once you can make the full central dogma, you’re actually really quite close to being able to make a mirror cell. Might not be the case. We don’t know for sure. But that, I think, is a way that this could happen relatively quickly.

Luisa Rodriguez: Super quickly. Crazy. Yeah, that hadn’t occurred to me at all. So that’s one breakthrough in mirror biology. Are there others worth talking about?

James Smith: It’s probably worth saying that we’ve been able to make mirror proteins and mirror DNA and mirror RNA for quite a long time. The challenge has been making big proteins, and we’re getting better at doing that.

Luisa Rodriguez: When you describe the problem of making big enough proteins that fold the way you need them to fold, that are quite complex, that does seem like a thing that AI would help quite a lot with. Is that true?

James Smith: I think it’s more likely that this is a trial-and-error type of problem, where you need to be doing a lot of experimentation. So AI could be helpful if it’s able to do a lot of this troubleshooting directly. But to do that, you’re going to need quite a lot of wet lab footprint — which doesn’t make it impossible, but means that I think it would be more difficult than a design task.

There are actually other pathways through which mirror life could plausibly be created. There’s one called the stepwise conversion pathway, which would basically mean you start with a normal cell and then you engineer it so that it can create mirror components within it. So you make a second ribosome that’s able to make mirror proteins and then gradually you convert it completely into a mirror cell. In that scenario, it’s possible that for engineering the ribosome, it could be helpful to use biodesign tools or something. I’m still not sure that it would be necessarily that helpful.

Another way AI could help is through engineering the genome to make it easy to boot. It might be the case that some genomes are just inherently easier to boot life from. Maybe you need to start in a certain place in the genome and do everything in a particular order to get it to work. Maybe you could be using genome design tools to think through that.

Luisa Rodriguez: Crazy. OK.

James Smith: There’s not going to be any data on this sort of thing, so I think we are talking about AI that would be very advanced, because it’s not going to have much to draw on.

Luisa Rodriguez: Yeah, it’s going to have to, from first principles, be like, “OK, if we create this one molecule first, that’s going to form the initial backbone that this other next one can then bind to” something, something, something.

Fascinating. I’m getting a tiny bit of the flavour of this does sound like cool research that people are doing. But yeah, we should remind ourselves that it is not very valuable and potentially catastrophic.

James Smith: It is really cool. I’m extremely sympathetic, and I think it makes complete sense that people wanted to do this. But the amazing thing is that the people who did want to do this are on the paper, have come forward and said that it’s not something they think should be done. So the people who were most interested in doing this stuff are now the ones that are saying that it shouldn’t be done. And I think that’s just a pretty amazing story.

Policies for governing mirror life research [01:06:39]

Luisa Rodriguez: OK, let’s talk about how we stop mirror life from being created practically. What kinds of governance structures or policies or treaties do you think are the right kind of approach for actually enforcing this thing that all these scientists seem to agree on, that we shouldn’t do this, we shouldn’t go there?

James Smith: So unless new evidence comes out that really changes this picture, I think three things would need to be true in the next, say, two to five years for me to feel comfortable that the mirror life problem was basically solved:

- The first is that I think there needs to be a strong norm against the work to make mirror life in the scientific community.

- The second is that I think there needs to be regulation of enabling technologies or precursor technologies, the things that we develop on the way to making mirror life.

- And the third is that governments need to be taking this seriously, such that they would deploy the kinds of capabilities that they use to stop terrorists from accessing nuclear weapons to the question of mirror life.

Luisa Rodriguez: How big are these asks? I can imagine it being the case that scientists kind of agree that we shouldn’t be making mirror enzymes, that that’s just too close to mirror bacteria. But on the synthetic biology side, maybe some of the things that you’d want to say are getting too close are the kinds of things that people would be really hesitant to stop work on.

You mentioned several different things that are necessary for this to be solved. Which of these are like, people will probably just say that yes, that’s reasonable, and which seem hard for people to buy into?

James Smith: I think on the norm against mirror life, there’s already been quite good progress. UNESCO, for example, have recently put out a report from their International Bioethics Committee recommending a global moratorium on mirror cells. The UK government has looked into this and written up some notes saying that they think mirror life creation should be prevented. This German expert committee has looked into it and endorsed the analysis of the risks. So I think there’s already quite good momentum on that point.

The second point, which is around the enabling technologies, I think is a much more difficult decision. The reason is because some of those technologies are things that people might want to work on in the near term. So you mentioned mirror enzymes, but actually people can already make quite a lot of mirror enzymes — and most of that I think is completely fine. There’s no reason to need to go back and try to do anything about work that’s already been done.

But there are things that could be done in the next six months or the next couple of years that some people think should not be pursued. One example there is the mirror ribosome. We already talked a bit about the mirror ribosome. It’s the most complex macromolecule that you would need to make to be able to make a mirror cell, so it’s quite a natural stopping point in a way. It’s also very well defined. But people in the US, people in China, people elsewhere, are interested in doing this because they think it might be helpful for manufacturing mirror therapeutics. So there’s an ongoing conversation at the moment around whether those potential benefits justify the risks of getting closer to mirror life.

Luisa Rodriguez: And how worried are you about making just mirror ribosomes? Does that feel like, if we do that and publish papers on it, that will make it too easy for rogue actors or something to do this and implement it in actual bacteria?

James Smith: We don’t really know how far away a mirror ribosome is from a mirror cell. It could turn out that there are still a lot of steps and things that make it difficult, but it also could turn out that it’s quite easy. And I think it’s going to be really difficult to know that in advance.

It is worth saying the mirror ribosome doesn’t pose any risk in and of itself. It can’t self-replicate, it can’t evolve, it doesn’t have these special risks that mirror life does have. So it’s all about how much closer it gets us to making mirror life. In fact, if it would be very difficult to go from there to making mirror life, then it might make sense for it to happen.

There are also different types of mirror ribosomes. You could make a basic mirror ribosome, but a mirror ribosome that’s really good at making proteins might be quite a bit harder to make than that. And that’s probably the sort of thing you’d need to be able to make mirror life.

Luisa Rodriguez: OK, that makes sense. Will we learn much more about what are the really hard steps here? It’s interesting to me that it’s hard to predict in advance. Is there any reason to think that we will actually find out that it’s not the mirror ribosome bit, but it’s like “bringing all the pieces together and animating them” bit? Or is that just like we probably can’t know, because we would like to stop before we do any experiments that shed light on that?

James Smith: I think we could learn more, especially from experiments on natural chirality cells. So there are these two areas that we’ve talked about, mirror biochemistry and synthetic cells — both of which ultimately you need to have progress in to be able to make a mirror cell. And we might learn things from natural chirality synthetic cells that tell us either that it’s very easy to go from a basic system with a membrane to life, or very difficult.

But there are hard questions that need to be answered on the synthetic cell side of things too. The challenge there is synthetic cells is a much bigger field, at least by some definitions, and there’s a lot more interest in pursuing that. So any kind of restriction or regulation there might impact more ongoing research, and that is a tradeoff.

Luisa Rodriguez: Right. What are the most contested debates on that side of things?

James Smith: One intuition here is that, if you get good enough at making synthetic cells, if you could make a completely artificial cell in the lab, then you could use the same methods to make a mirror cell, because the chemistry would all be the same. So if this got really advanced, then you might be quite close to making mirror cells.

But we’re not really very close to that at the moment. In reality, when people are talking about synthetic cells, they mostly are using some parts that are derived from life. And if you’re using parts that are derived from life, then you can’t immediately replicate that on the mirror side of things.

Luisa Rodriguez: Just to make that more concrete, it’s something like — I’m sure this is not actually it — but if you could use some subcomponent of a ribosome to create a full ribosome, that might help you a lot in synthetic biology, but it doesn’t help you with mirror life because we won’t be starting out with that half ribosome to then build on?

James Smith: Yeah. In mirror life, at least from the bottom-up pathway, you have to make everything from scratch, and that makes it a much more difficult problem. In some ways there’s not a great reason why you’d want to make everything from scratch on the natural chirality side of things, so that helps you to some extent.

But I think it is a long-term goal of science to be able to make life completely artificially, so eventually we are going to have to think about what’s an appropriate line there. I think we can probably get a lot of the benefits of synthetic cells without making them completely artificially. So I think we need to think about what lines there would neatly delineate the things that get us too close to mirror life and don’t. But this is a topic that a lot of people need to weigh in on.

Luisa Rodriguez: Yeah. Are there arguments for doing at least that particular thing, creating a cell from total scratch, that aren’t just to do with it sounds really cool, and it makes sense that people would be keen to do it because it would be a really massive achievement? To what extent are we giving things up by drawing lines before that?

James Smith: I think this is mostly an area of blue skies research. We’ve been having discussions with a lot of the people doing this work over the last few months, and I haven’t heard a specific benefit of completely artificial life be articulated. The idea is more that you could generally manipulate life, and if you understand it really well, you can do that better. So you could do a myriad of different things. But I do think a bit more critical thinking is needed in terms of whether you could achieve those benefits the other way.

One example is you might be able to just transplant genomes that have all of the characteristics that you need into cells, and then you basically have the cell be defined by the genome instead of booting it up from all of its individual components. That might get you basically the same benefits.

Luisa Rodriguez: Yep. OK, that makes sense. For people who are going to be sceptical of governance that stops some synthetic biology research, what are the fair things that you concede that we’d be giving something up? And maybe you think we still should, but are there types of research that probably we shouldn’t do, where you can actually see a point to it that’s instrumental?

James Smith: The things we’ve been talking about are the foreseeable benefits of making mirror life or making the technologies on the way to doing it. A lot of science is done without a specific application in mind, and usually I think that’s a good thing. We should have a prior on scientific progress being good, given the results that it’s produced historically. In this case, we have to weigh that up against what I think is pretty overwhelming evidence of the risks, and I don’t think it’s sufficient.

One thing that I think is really important to say is that synthetic biology as a whole is a really big field that has a huge range of benefits that I do buy into. Synthetic cells are a relatively small part of that, and within synthetic cells, I think there are a lot of applications that will ultimately be important. Mirror life, and mirror biochemistry, and possibly some specific synthetic cell experiments that might not make sense to do are a tiny part of the technology tree. So it’s not like by not pursuing this, we’ll be giving up a huge area of science. This is one very tiny area of the technology tree that we could choose not to go down.

Luisa Rodriguez: It just sounds like the arguments are really compelling. The benefits are not that big and are going to be reasonably easy to accept that we’re going to give them up. How optimistic are you that as you and this group take more next steps, you’ll get the policy and governance measures you think are really important passed and in place?

James Smith: That’s a really hard question to answer. I think we’ll get some better answers to some of the most important questions within the next year or so. But then it’s going to be a really hard road to go from there to implementation.

And a lot more people are needed to think through how exactly that will work. Each different country might have a different regulatory framework to think through something like this. And there’s only a really small group thinking about this at the moment, who are not going to be experts in all the things necessary. So this is one of the areas where we really need more people to come in and think about how this should go.

Luisa Rodriguez: How hard do you expect it to be to get these kinds of policies passed? I guess one question that comes to mind is, have we successfully implemented global regulation on a scientific technology like this before?

James Smith: Yeah, we have actually. There are some really good examples here. One is the Environmental Modification Convention, which I didn’t know about until quite recently, but basically this is a treaty that quite a lot of different countries signed on to in the late ‘[7]0s, prohibiting the use of environmental modification as a weapon. So that means using weather as a weapon.

Luisa Rodriguez: Right. Interesting.

James Smith: The US and the USSR both signed onto this and collaborated on it. It’s a super interesting one. I’d love to know a bit more about the history, but it is an example of a technology that didn’t exist being prohibited well in advance. So I think this is one example.

Luisa Rodriguez: Yeah, nice.

James Smith: Other areas include the Montreal Protocol, which is one of the most successful examples of an international treaty, prohibiting ozone depleting substances. There’s also a really not well-known treaty prohibiting the use of blinding weapons like lasers. Things like this have been agreed to before, so I think there is actually quite a lot of precedent showing that we can identify something that doesn’t yet exist and decide not to pursue it.

Luisa Rodriguez: I also thought of cloning, but I wonder if cloning is a slightly mixed example, because there is agreement that we shouldn’t be cloning humans. But I feel like I’m remembering that some people ignore this and do it anyways. Do you worry about that with mirror life? And also maybe fact-check my cloning thing?

James Smith: Yeah. So human cloning no one has done. In 1996, Dolly the sheep was cloned. And then there was this big discussion that ultimately resulted in people agreeing that human cloning shouldn’t be done. That’s an interesting example where the technology is kind of in principle there to do this, but no one has actually gone ahead and done it.

The thing that you’re thinking of is human germline editing, which is a different technology. What that demonstrates to me is that a norm on its own that lets you go right up to the edge of being able to do something is not sufficient, because you can’t assume that people are always going to go along with a regulation or with a norm. So that means you need to draw lines earlier on that mean that if people cross those lines, there’s still space between where they are and the thing that you’re worried about.

Luisa Rodriguez: And the bad thing. OK, that makes a lot of sense.

Countermeasures if mirror bacteria are released into the world [01:22:06]

Luisa Rodriguez: OK, I want to come back to how people can maybe get involved, and what the next steps are for this project. First, we’ve talked a bit about some of the countermeasures that might and might not work. Are there any potential countermeasures like vaccines or something else that you think are really promising that we haven’t talked about yet?

James Smith: Yeah, I think there are. You can use conjugate vaccines to kind of trick the body into having a robust response against basically anything. So you can use them to trick the body into making antibodies against cocaine. You could do the same potentially for mirror components, and that’s something that I think is worth exploring in some more detail.

More generally, physical countermeasures should be helpful against mirror bacteria. So as a kind of plan B backup if prevention doesn’t work, I do think investing in robust biodefence that’s kind of threat agnostic could be very valuable, and is something that people should think about doing.

Luisa Rodriguez: Can you give specific examples? I’m picturing Bubble Boy again, basically.

James Smith: That might be the extreme. But in the nearer term, things like PPE, biohardening, possibly early warning systems — some of the things that Andrew Snyder-Beattie talked about on a recent podcast on 80,000 Hours: I think many of those could help for a mirror bacteria outbreak too.

Luisa Rodriguez: I am kind of interested in early warning systems. Would we know, if we started seeing deadly infections in hospitals, that they were caused by mirror bacteria? How difficult would it be to notice that?

James Smith: That’s a really good question. A lot of the methods that we use to detect things use enzymes that wouldn’t work for mirror life because of the chirality of them. PCR is an example here, which is used to kind of amplify DNA. We can actually already make all of the enzymes in PCR in the mirror form, so we could in principle use those enzymes as a detection method. But at the moment, we’re not set up to do that.

Luisa Rodriguez: We’re not. Are there other biodefence-y things that you think are promising?

James Smith: I think more work on antibiotics could be good. I’m not sure whether it makes sense to develop new antibiotics or just think through the ones that already exist and figure out how best we could scale them up. But people thinking through that problem might be beneficial.

One set of countermeasures that I don’t think will work and that the world is investing a lot in are mRNA vaccines and DNA vaccines. Because the way those work is they use your cells to create proteins from them: so you put an RNA vaccine into your body and then the cells make a protein from the RNA, and then you have an immune response against that. If you were injecting mirror RNA, your cells can’t read that genetic code, so it won’t work.

Luisa Rodriguez: Right. Lovely.

James Smith: So unfortunately, some of the platforms that we’re doing the best at are not going to work here, and different approaches I think would be needed.

Luisa Rodriguez: OK. Those are some countermeasures that would and wouldn’t work mostly in the context of humans. I can imagine many of those things also helping with nonhuman animals, but maybe plants are quite a different issue. And maybe in particular, thinking about countermeasures for crops is super important. Are there any that seem promising there?

James Smith: Yeah. We could actually engineer crops to be able to detect mirror bacteria infections. We could probably engineer them so that some of their pattern recognition receptors were able to bind to some of the common molecules on mirror bacteria.

This is something that also might be worth some further research. I think we can do that probably to protect a small number of critical crops. You’re going to have to do that for basically every species that you want to protect, so it’s very difficult to scale so that you could protect the Amazon rainforest and all the different plants in a forest near you. But it could be done for some key crops, I think.

Luisa Rodriguez: Can you help give an intuition for why that is so hard to do at scale? Intuitively, we engineer crops all the time. Why can’t we just do that?