#97 – Mike Berkowitz on keeping the U.S. a liberal democratic country

#97 – Mike Berkowitz on keeping the U.S. a liberal democratic country

By Robert Wiblin and Keiran Harris · Published April 20th, 2021

On this page:

- Introduction

- 1 Highlights

- 2 Articles, books, and other media discussed in the show

- 3 Transcript

- 3.1 Rob's intro [00:00:00]

- 3.2 The interview begins [00:02:01]

- 3.3 What we should actually be worried about [00:05:03]

- 3.4 January 6th, 2021 [00:11:03]

- 3.5 Trump's defeat [00:16:44]

- 3.6 Improving incentives for representatives [00:30:55]

- 3.7 Signs of a loss of confidence in American democratic institutions [00:44:58]

- 3.8 Most valuable political reforms [00:54:39]

- 3.9 Revitalizing local journalism [01:08:07]

- 3.10 Reducing partisan hatred [01:21:53]

- 3.11 Should workplaces be political? [01:31:40]

- 3.12 Mistakes of the left [01:36:50]

- 3.13 Risk of overestimating the problem [01:39:56]

- 3.14 Charitable giving [01:48:13]

- 3.15 How to shortlist projects [01:56:42]

- 3.16 Speaking to Republicans [02:04:15]

- 3.17 Patriots & Pragmatists and The Democracy Funders Network [02:12:51]

- 3.18 Rob's outro [02:32:58]

- 4 Learn more

- 5 Related episodes

James Madison helped draft the US Constitution, and like today's guest was very concerned with ensuring it would hold up even when the public elected bad officials.

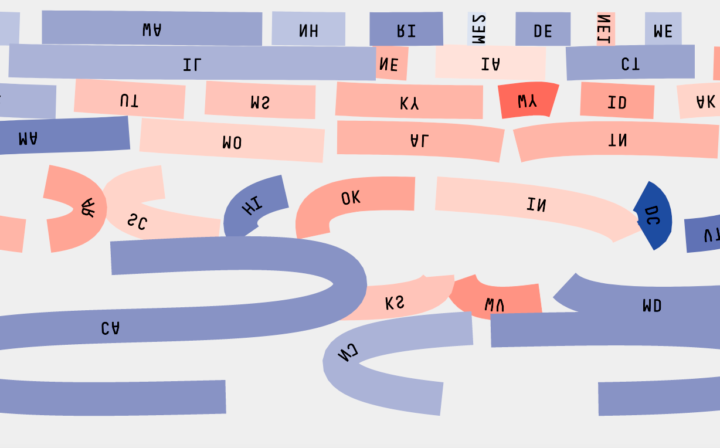

Donald Trump’s attempt to overturn the results of the 2020 election split the Republican party. There were those who went along with it — 147 members of Congress raised objections to the official certification of electoral votes — but there were others who refused. These included Brad Raffensperger and Brian Kemp in Georgia, and Vice President Mike Pence.

Although one could say that the latter Republicans showed great courage, the key to the split may lie less in differences of moral character or commitment to democracy, and more in what was being asked of them. Trump wanted the first group to break norms, but he wanted the second group to break the law.

And while norms were indeed shattered, laws were upheld.

Today’s guest Mike Berkowitz, executive director of the Democracy Funders Network, points out a problem we came to realize throughout the Trump presidency: So many of the things that we thought were laws were actually just customs.

So once you have leaders who don’t buy into those customs — like, say, that a president shouldn’t tell the Department of Justice who it should and shouldn’t be prosecuting — there’s nothing preventing said customs from being violated.

And what happens if current laws change?

A recent Georgia bill took away some of the powers of Georgia’s Secretary of State — Brad Raffensberger. Mike thinks that’s clearly retribution for Raffensperger’s refusal to overturn the 2020 election results. But he also thinks it means that the next time someone tries to overturn the results of the election, they could get much farther than Trump did in 2020.

In this interview Mike covers what he thinks are the three most important levers to push on to preserve liberal democracy in the United States:

- Reforming the political system, by e.g. introducing new voting methods

- Revitalizing local journalism

- Reducing partisan hatred within the United States

Mike says that American democracy, like democracy elsewhere in the world, is not an inevitability. The U.S. has institutions that are really important for the functioning of democracy, but they don’t automatically protect themselves — they need people to stand up and protect them.

In addition to the changes listed above, Mike also thinks that we need to harden more norms into laws, such that individuals have fewer opportunities to undermine the system.

And inasmuch as laws provided the foundation for the likes of Raffensperger, Kemp, and Pence to exhibit political courage, if we can succeed in creating and maintaining the right laws — we may see many others following their lead.

As Founding Father James Madison put it: “If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary.”

Mike and Rob also talk about:

- What sorts of terrible scenarios we should actually be worried about, i.e. the difference between being overly alarmist and properly alarmist

- How to reduce perverse incentives for political actors, including those to overturn election results

- The best opportunities for donations in this space

- And much more

Get this episode by subscribing to our podcast on the world’s most pressing problems and how to solve them: type 80,000 Hours into your podcasting app. Or read the transcript below.

Producer: Keiran Harris

Audio mastering: Ben Cordell

Transcriptions: Sofia Davis-Fogel

Highlights

What we should actually be worried about

Mike Berkowitz: I think one can be overly or properly alarmist about these questions, and I try to be properly alarmist about them. I don’t think that the threat is a dictatorship or totalitarian state as we saw in the 20th century. We don’t see the decline of democracy or the deterioration or deconsolidation, as political scientists refer to it, of democracy around the world. We don’t see a lot of violent conflict. We don’t see coups or revolutions. We actually see a much more subtle chipping away at the foundations of liberal democracy.

Mike Berkowitz: So the things that worry me are kind of a version of illiberal democracy, where we might have elections, but we don’t have some of the protections of small-l liberalism, the rule of law, separation of powers, individual rights, things like that. Or we might think about it as sort of a soft authoritarianism. Those are the things that I’m worried about. And we see them in other states around the world. You see these things in places like Russia, Turkey, Brazil. You might have elections, but are they free and fair? You might have separation of powers on paper, but as we are seeing in the United States, more and more power is being vested in the executive branch. I worry about restrictions on civil society that we see around the world, the consolidation of media into the hands of the few. These are the kinds of things that I worry about much more so than a sort of prototypical 20th century authoritarian state.

Improving incentives for representatives

Mike Berkowitz: So this is where I think both political leadership and political structures and incentives really do matter. On the one hand, one can look at leadership here and say, if Donald Trump hadn’t been making the claim and pushing others to make the claim that the election was stolen, we wouldn’t have seen hardly any of the actors who abided by that falsehood do so last year. I just really don’t think we would have seen that. Donald Trump’s popularity and power within the Republican Party also forced their hand to some extent. Again, I think it was the wrong calculus on many levels, but he really did box many Republican politicians in by taking that position.

Mike Berkowitz: But to your point, this is also where incentives and structures really do matter. And I think we’ve realized that even the best politicians, even the most courageous and moral, and ethical ones are working within a system that has particular incentives to it. And so there’s a lot of political reform efforts that are out there right now that are really looking at this question. For instance, there was just a report that came out, I believe it was called The Primary Problem by a group called Unite America, just out this week, and they really talk about the problem of partisan primaries, where you have the most ideologically committed voters within a party turn out in what’s almost always a low-turnout election. This is the way primary elections are. And the incentives, then, if you are trying to win a partisan primary, are to be more partisan. You’re trying to get your base.

Mike Berkowitz: And so therefore you wind up with more ideologically extreme candidates in general elections. And again, because people largely vote based on the hat that they wear, the R or the D in American democracy next to a candidate’s name, it almost doesn’t matter how extreme a candidate is in many districts because those districts are so safe, they’re going to win regardless. So I do think political reforms are important here. I’m a little agnostic personally about which ones, we could talk more about this, but I do think some reforms to the system are really key to get at the structures there as well.

Most valuable political reforms

Mike Berkowitz: I think we have to change some of the incentive structures and see what happens. It was noted that Lisa Murkowski, a Republican senator from Alaska, was the first senator on the right to come out in favor of Donald Trump’s impeachment after January 6th. Well, that also happened after Alaska had passed a set of voting reforms, including final-four voting, where there were no longer going to be partisan primaries, there will be an open primary and the top four vote getters will move on to the general election and there will be ranked-choice voting. So you’ll get to list your preferences among the final four candidates. And that is thought to enable more candidates to appeal to a wider segment of the population. So it was noted that this reform may have played a significant role in Murkowski being able to come out as quickly as she did and as forcefully as she did on Donald Trump’s impeachment. So political reforms I think are key.

Mike Berkowitz: One of the most promising ones on the voting front, for instance, is automatic voter registration. It’s a little bit odd and probably not coincidental in the United States that when a boy turns 18, he’s automatically drafted into the selective service. That happens without him doing anything, and means he could be on call for military service at some point. But one has to proactively register to vote to avail oneself of that right in our system. I should note, it’s not a constitutional right, there is no right to vote in the U.S. constitution, which I think is also a challenge here.

Mike Berkowitz: And so automatic voter registration is at least one I think quite popular reform — not just on the left, but it actually has some adherence across the political spectrum. It basically says that when you go to get a driver’s license, for instance, you’re automatically enrolled to vote. So that’s a really, really key reform on the voting rights front. I do think expanding the ability to vote by mail is really key, I think we saw a lot of that.

Mike Berkowitz: I would love on the redistricting front to see us get rid of partisan redistricting. I think that the incentives there are just all wrong. And I think it’s clear that we need independent [missions], not that they’re easy to implement or figure out, there’s still lots of challenges, but I would like to see us move away from partisan redistricting. When it comes to reforms about how we elect our representatives, that’s where I’m much more agnostic.

Revitalizing local journalism

Mike Berkowitz: I think our politics, at least here in the United States, are much less polarized at the local level than they are at the federal level. And so when we are paying attention to federal politics, we’re seeing the worst manifestations of political polarization and that is affecting the way that we understand our democracy and understand our politics right now. And so the more that we can be focusing at the local level where there is, as you said, a lot of common concerns that don’t fall along traditional — and traditional in this sense really means national or federal — political lines… And that’s part of what we need to overcome the polarization in our country, is to cross-cut some of those standard divisions.

Mike Berkowitz: The other thing is that there’s a presumption, which I think is probably true, that one of the challenges that is afflicting American democracy is a lack of felt agency. That as people look out at the world they see a growing federal government and bureaucracy, and that bureaucracy includes many parts of it that are unelected, because you elect the president, you elect the senator and you elect your representative, but you don’t elect the other members of the executive branch, for instance. And the executive branch is huge, it has lots and lots of employees and different departments, and so there are a proliferating number of decision-making bodies that people literally have no control over.

Mike Berkowitz: And then you get to an environment in which we, for good reasons, have to be engaging with other countries to make international policy on things like human rights or climate change, and that is even less connected to people’s ability to influence things. So then when you think about, “Where can we actually have an impact in our democracy, where can we feel connected to it?” it’s at the local level. There are just so many more opportunities there to see and touch and feel, to have an impact, to get to know people, to know the issues. And so I think we need more of that. It’s actually a weakness, I would say, of progressive politics.

Mike Berkowitz: Over the last half century, we’ve put so much effort…I don’t want to malign the reasons why this happened, but we’ve put so much effort into national politics. And by the way, also into the judicial system, where again, people don’t have an ability to control or influence that. We’ve put so much emphasis there that we’ve moved people’s attention away from the things that they can feel connected to that are really the bread-and-butter of democracy.

Reducing partisan hatred

Mike Berkowitz: One thing is we just have to find ways to get out of our bubbles. Now, this is really hard to do right now, because as we’ve talked about, we are geographically sorting, and so we live with fewer and fewer people who we disagree with, but it’s a key piece. We also have to understand that in a pluralistic democracy, certainly one like the United States that has 330 million people, people are going to have different views, we’re not all going to see things the same way. And part of the project here is we have to get comfortable with that, we have to be okay with it. And when we are in a social cohesion/building frame in particular, we need to not see our project as trying to convince other people to see things the way that we do. There has to be tolerance for different views, that is what pluralism is.

Mike Berkowitz: We have to be able to live together in a society, in a political community, recognizing that we have differences, and fighting for those differences. And by the way, this is not a call for trying to get along all the time for a consensus — we should have deeply held political beliefs, and when we have them, we should fight for them. But we also need to recognize at the end of the day that other people are fighting for their deeply held beliefs too. And however wrong we might think they are, we’re going to have to accommodate one another in one way or another. We can’t have total defeat in a democracy, certainly not in a pluralistic one.

Mike Berkowitz: We need to get out more and do things together that take us outside of our standard partisan divisions. There’s a group I often like to point to in this instance called the One America Movement, which gets people across lots of different lines of difference in their communities to actually go out and do projects together of common interest and concern — volunteering, community service, helping rebuild after a natural disaster.

Mike Berkowitz: When you take people out of the red/blue partisan divide and actually put them in their communities doing things where they have shared concerns, you cross-cut, again, those political identities and build new identities. And it’s in those new identities that we can start to find some way to cohere. We also need more in-group moderates. So this is a term of art and it doesn’t actually refer to political moderates or centrists, what it refers to is people who are willing to stand up against the worst impulses of their own side. It’s very easy to criticize the other side of the aisle, but it’s much harder to criticize your own — but it’s actually the key thing to creating political communities that are willing to act with some moderation and some forbearance for the other side.

Articles, books, and other media discussed in the show

Organizations and projects

- Democracy Funders Network

- Patriots & Pragmatists

- Democracy Alliance

- New America

- American Journalism Project

- One America Movement

- Braver Angels

- League of Women Voters

- Public Citizen

- Common Cause

- Indivisible

- Voting Rights Lab

- Protect Democracy

- Campaign Legal Center

- NAACP Legal Defense Fund

- Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

- Over Zero

- More in Common

- Republican Voters Against Trump

- Republican Accountability Project

- Third Plateau

Books

- How Democracies Die, by Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt

- The People vs. Democracy: Why Our Freedom is in Danger and How to Save It, by Yascha Mounk

- The Politics Industry: How Political Innovation Can Break Partisan Gridlock and Save Our Democracy, by Katherine M. Gehl and Michael E. Porter

- Divided We Fall: America’s Secession Threat and How to Restore Our Nation, by David French

- Politics Is for Power: How to Move Beyond Political Hobbyism, Take Action, and make Real Change, by Eitan Hersh

Articles and reports

- What Comes Next? Lessons for the Recovery of Liberal Democracy

- Our Common Purpose

- Hidden Tribes

- The Secret History of the Shadow Campaign That Saved the 2020 Election, in Time by Molly Ball (see also Irresponsible Hype from Molly Ball and Time Magazine)

- The New Era of Progressive Federalism

- The Primary Problem

Trevor Potter on The Colbert Report

- Colbert PAC, March 30, 2011

- Colbert Super PAC, April 14, 2011

- FEC Questions, May 31, 2011

- Colbert Super PAC – Trevor Potter Preps Stephen for His FEC Hearing, June 29, 2011

- Colbert Super PAC and Stephen’s Shell Corporation, September 29, 2011

- Colbert Super PAC – Issue Ads, November 7, 2011

- Colbert Super PAC – Coordination Resolution, January 12, 2012

- Colbert Super PAC SHH! – 501(c)(4) Disclosure, April 3, 2012

- Colbert Super PAC SHH! – Secret Second 501(c)(4), November 12, 2012

- Mazda Scandal Booth – The IRS, May 20, 2013

Other links

Transcript

Table of Contents

- 1 Rob’s intro [00:00:00]

- 2 The interview begins [00:02:01]

- 3 What we should actually be worried about [00:05:03]

- 4 January 6th, 2021 [00:11:03]

- 5 Trump’s defeat [00:16:44]

- 6 Improving incentives for representatives [00:30:55]

- 7 Signs of a loss of confidence in American democratic institutions [00:44:58]

- 8 Most valuable political reforms [00:54:39]

- 9 Revitalizing local journalism [01:08:07]

- 10 Reducing partisan hatred [01:21:53]

- 11 Should workplaces be political? [01:31:40]

- 12 Mistakes of the left [01:36:50]

- 13 Risk of overestimating the problem [01:39:56]

- 14 Charitable giving [01:48:13]

- 15 How to shortlist projects [01:56:42]

- 16 Speaking to Republicans [02:04:15]

- 17 Patriots & Pragmatists and The Democracy Funders Network [02:12:51]

- 18 Rob’s outro [02:32:58]

Rob’s intro [00:00:00]

Hi listeners, this is the 80,000 Hours Podcast, where we have unusually in-depth conversations about the world’s most pressing problems, what you can do to solve them, and my favourite clips from 2012 late-night comedy shows. I’m Rob Wiblin, Head of Research at 80,000 Hours.

Last year, my colleague Arden Koehler wrote a post that listed over 30 pressing global issues beyond the ones we talk the most about, which we think our audience might consider focusing their career on tackling.

One of those was ‘Safeguarding liberal democracy’. Arden noted a great deal of effort already goes into understanding the conditions under which liberal democracy is typically strengthened, and the ways in which they get undermined, and that we didn’t really know what was most effective way to help.

So, continuing our theme of exploring new problems areas, we wanted to find out what could really be done, from someone actually working in the area.

When we asked around it seemed like one of the best people in the world to talk to about this would be today’s guest, Mike Berkowitz, a philanthropic advisor who works on ensuring the US remains a democratic country for the long term.

To my knowledge this is the first long-form interview Mike has ever done, and I think we’ve uncovered a real gem here. He’s both highly informed and a great speaker.

Mike and I cover his picks for the three most important levers to push on to try to shore up the political situation in the United States:

- Reforming the political system, such as introducing new voting methods

- Revitalizing local journalism

- Reducing partisan hatred within the United States

We also talk about:

- What sorts of terrible scenarios we should actually be worried about

- How to reduce the incentive for representatives to attempt to overturn election results

- The best opportunities for charitable giving in this space

- And much more.

If you’re curious, you can find those dozens of other potentially pressing global issues beyond our current priorities at 80000hours.org/problem-profiles/.

Finally — yep, your eyes do not deceive you, the show has a new logo. We hope you like it!

Alright, without further ado, here’s Mike Berkowitz.

The interview begins [00:02:01]

Robert Wiblin: Today, I’m speaking with Mike Berkowitz. Since 2010, Mike has led Third Plateau, an advisory group for impact-oriented philanthropists focused on social and political problems in the United States. He is a certified philanthropy consultant and has counseled numerous individual donors, family foundations, and institutional foundations on their philanthropic strategy.

Robert Wiblin: More recently, in response to the rise of political populism in the United States, Mike has become the executive director of the Democracy Funders Network, a community of major U.S. donors concerned about the underlying health of American democracy. He has also co-founded Patriots & Pragmatists, a cross-partisan coalition of donors, writers and advocates focused on ensuring the U.S. remains a liberal democratic country.

Robert Wiblin: Many years ago, Mike studied history at Brown University. Today, as you might guess from the above, he is focused on helping donors figure out how they can use their resources to ensure that the U.S. remains a functional democracy. Thanks for coming on the podcast, Mike.

Mike Berkowitz: Thanks for having me.

Robert Wiblin: I hope to get to talk about the work that you’ve been doing over the last four years and how listeners might be able to help with your mission. But first, what are you working on at the moment and why do you think it’s important?

Mike Berkowitz: I’ll start actually with a couple of things that you already touched on. Broadly speaking, as you noted, my work at the moment is really focused on sustaining liberal democracy in the United States for the next 50 to 100 years, which is a big challenge that I’m excited to talk more about today. One mechanism that I’m doing that through is a group called Patriots & Pragmatists, we refer to it as P&P. P&P is a cross-ideological network and convening space for civic leaders and influencers to make some sense together of what’s happening to American democracy and what to do about it.

Mike Berkowitz: It emerged organically after the 2016 election, when my client/colleague/friend Rachel Pritzker and I realized that there was nowhere to go to engage in an ongoing strategic conversation about American democracy across disciplinary and ideological lines. The key insight here was that when it comes to saving democracy, that can’t be something that only happens on one side of the political spectrum. If it does, then democracy is as polarized a political issue as anything else. And we can talk more about whether that is the case at the moment. The political scientists Daniel Ziblatt and Steven Levitsky, in this great book How Democracies Die, talk about this actually. They say that the way that you save democracy is not through coalitions of the like-minded, it’s through coalitions that bring together people with dissimilar views. And so that’s been a key part of my work.

Mike Berkowitz: The Democracy Funders Network emerged from Patriots & Pragmatists as more and more donors came to realize that American democracy is not a guarantee, it’s actually something we need to fight for. And so we’re a cross-ideological learning and action community for donors who are concerned about the health of American democracy. So those are the kind of big projects that I’m working on at the moment.

What we should actually be worried about [00:05:03]

Robert Wiblin: What are the sorts of future terrible scenarios that you’re trying to help avoid becoming real, just to try to make things concrete?

Mike Berkowitz: That’s a great question because I think one can be overly or properly alarmist about these questions, and I try to be properly alarmist about them. I don’t think that the threat is a dictatorship or totalitarian state as we saw in the 20th century. We don’t see the decline of democracy or the deterioration or deconsolidation, as political scientists refer to it, of democracy around the world. We don’t see a lot of violent conflict. We don’t see coups or revolutions. We actually see a much more subtle chipping away at the foundations of liberal democracy.

Mike Berkowitz: So the things that worry me are kind of a version of illiberal democracy, where we might have elections, but we don’t have some of the protections of small-l liberalism, the rule of law, separation of powers, individual rights, things like that. Or we might think about it as sort of a soft authoritarianism. Those are the things that I’m worried about. And we see them in other states around the world. You see these things in places like Russia, Turkey, Brazil. You might have elections, but are they free and fair? You might have separation of powers on paper, but as we are seeing in the United States, more and more power is being vested in the executive branch. I worry about restrictions on civil society that we see around the world, the consolidation of media into the hands of the few. These are the kinds of things that I worry about much more so than a sort of prototypical 20th century authoritarian state.

Robert Wiblin: How much do you worry about trends like say, significant increases in voter suppression, or say, significant increases in gerrymandering or perhaps state legislatures taking over the role of appointing the electoral college, such that there’s still elections, but they are significantly less reflective of the views of the American public?

Mike Berkowitz: Yeah. So I’ll say two things here. So one is just as a contextual point because I think it often gets lost in discussions about democracy. I want to say that democracy is about more than just voting. And one of the challenges that I think we had prior to 2016 is our conception of what a healthy democracy looked like in the United States was pretty narrow. We thought a lot about voting, gerrymandering, and campaign finance. We didn’t think a lot about the issues that the United States was actually working on abroad to help countries develop their democracies.

Mike Berkowitz: But the second thing that I would say is I’m really concerned about efforts to suppress the vote, to create minoritarian rule in the country. And I think that there are a lot of ways in which the efforts that we’re seeing at the state level, in a variety of states… There’s over 250 bills that have been introduced this year across 43 states to roll back voting rights to make it harder for people to participate in democracy and to warp what representation looks like. I think those are real threats, and they are characteristics of elections that are not quite free and fair.

Robert Wiblin: What motivated you to switch into working on this issue? I think beforehand, you’d been doing more traditional progressive campaigning or campaigning in favor of issues that the Democratic Party has supported, but you’ve now moved onto something that is aiming to be significantly less partisan than that.

Mike Berkowitz: Yeah. So one of the major disjunctures for me in my career was actually I had started out really in politics, I’d done some work on political campaigns, including on John Kerry’s presidential campaign in 2004 as a consultant. And when Kerry lost, I realized that I really wanted to focus on long-term efforts to create political and social and cultural change. I didn’t want to just work on campaigns where if you lost, you had nothing to show for your efforts. And so I got really involved in building the progressive movement and building what we refer to as progressive infrastructure. I was a consultant to a group called the Democracy Alliance — which is a network of major progressive philanthropists — from its launch in 2005 up until about 2009. And that work was really intended to strengthen the ability of the progressive movement to create change on the issues that we care about.

Mike Berkowitz: I left that work to start my own firm in 2010 with a broader mandate than just working in progressive politics, but there was also something about the experience of being part of an ideological community that — while I still believe deeply in the issues that we were working on — in some ways felt intellectually stifling and a little bit narrow. So I was probably predisposed when the 2016 election came around to be thinking about it, not just in conventional partisan terms.

Mike Berkowitz: And this was the most striking thing to me actually about 2016, is that there weren’t that many of us who fell into that camp. There were certainly a number, and interestingly, they were on both left and right, but what really led me into democracy work was a sense that we weren’t taking the threat seriously enough, that we were only really looking at it as a society or, within the progressive movement that I had come out of, in very conventional terms. People were talking about how Democrats were going to win in 2018 and 2020. While that was really important, I felt like we needed to pay attention to some of the deeper drivers and deeper challenges that were afflicting American politics and democracy.

January 6th, 2021 [00:11:03]

Robert Wiblin: What have you thought about the events over the last six months? I guess I’m particularly thinking of the protests or the riots on the 6th of January. I suppose they suggest that there’s a lot more work to do, and maybe we’re nowhere near fixing these issues. But it also suggests that you’ve maybe been prescient by five years ago getting on board with issues that seem to have become more pressing over time.

Mike Berkowitz: It’s interesting because I think on the one hand it does feel somewhat prescient and on the other hand, one didn’t need to be particularly prescient to see it. And this is to go back to alarmism, one only needed to be properly alarmist to see what was happening. I don’t want to say that January 6th was inevitable, but for those of us who were paying attention, we knew that something like that was going to happen. And I’ll just say this in two ways.

Mike Berkowitz: One is that we knew that there was going to be a continued rise in political violence. And we can talk a bit more later about some work that I helped to do that really started to take seriously the issue of political violence within the United States. But those of us who were engaged in that work knew that that would happen and that elections in particular are flashpoints, as we’ve seen around the world for violence and in particular for political violence. And so it was somewhat inevitable in that respect.

Mike Berkowitz: The other way is that we knew that there was going to be some contestation of the election results by Donald Trump. He had telegraphed that quite clearly, going back all the way to 2016. And I’d been involved in a number of efforts to really think through what that might look like and what it might do to our politics and to our society. And so the events of January 6th in some ways were, again, an almost inevitable culmination of an attempt to say that the election was stolen by the person who was about to have his electoral victory certified as it were by Congress.

Mike Berkowitz: So I find what happened on January 6th really disturbing. In some ways the most disturbing part to me though, is the way in which it too has become a polarizing partisan issue. There are folks on the left who sort of properly can see what that set of events were. There are some folks on the right, but the large majority of the Republican Party is in some version of denialism about that, with the former president even as recently as a week or so ago claiming that there was no real violence associated with January 6th. We saw Senator Ron Johnson from Wisconsin make comments that he felt comfortable on January 6th because he knew the people who were coming in. So it’s disturbing not just for the set of factors that led to it or what it produced itself in terms of death and destruction or the symbolic challenge that it offers around the world, but it’s also the reaction to it that causes me a lot of concern and leads me to agree with your point that we’re not out of the woods in any sense of the word.

Robert Wiblin: The polling I’ve seen suggests that if you survey a broad cross section of Americans, that the great majority of them have a negative view of what the rioters were doing on the 6th of January. But it seems like there is a meaningful minority, I guess overwhelmingly Republicans, who have either a delusional view or they recognize what happened and think that it’s good. It’s very scary to see. It seems like most elected Republicans are siding with that group, I guess because they’re most worried about that group because they’re the most activist and the most likely to primary them or hassle them. So even if they’re going against the views of 70% of the population, they’re kind of cowed by this very vocal minority.

Mike Berkowitz: Yeah. I think that’s right. I mean, I hesitate to make any guesses as to what is going on in the minds of Republican politicians these days. But I think it is clear enough that they are really scared of the base. And not without some cause. If your goal is to maintain power, then it’s reasonable — even though I think it’s the wrong calculus on many levels, moral, ethical, and otherwise, it’s the wrong calculus to me, to be cowed by them — but it is a real factor and it is a real force and I think it’s leading to all sorts of bad behaviors. And in some ways, this I think is one of the key challenges that we face in American democracy, at least right now. It should be clear and obvious that if a member of your party is breaking from the norms, traditions, values, institutions of liberal democracy, that that’s an opportunity for you to break away from that person or that set of actors and not just to stick with them because they have your party or your tribe’s name next to theirs.

Mike Berkowitz: But that’s not what’s happening. What’s happening is that democracy really is becoming polarized. And we see people largely sticking with their political coalitions, though not entirely. And this is where I think there’s some opportunity, but by and large, they’re sticking with their coalitions and just to put it really bluntly, Republican voters are largely staying with the party even though it is abandoning a lot of the principles that this country was built on and that Republicans cared deeply about as far as I can tell up until the last decade or so.

Trump’s defeat [00:16:44]

Robert Wiblin: In a minute we’re going to zoom out to the bigger picture and hear what you think should be done with this 50- or 100-year timescale perspective. But yeah, to begin with, let’s continue thinking about the concrete situation that we’re in now with Trump and the 2020 election and the fight over its legitimacy. How important do you think Trump’s loss was in the general global fight against democratic decay that we’re seeing today?

Mike Berkowitz: I think it was very important. The scholar Yascha Mounk has said, I think correctly, that we don’t often have the chance to defeat authoritarian populists. And so just to see it happen and to see the massive effort both obviously on the political side, but even just on the civil society side, where folks were fighting, not against Donald Trump, but to protect the norms, values, and institutions of American democracy. I mean, there’s a lot to learn from that. And so I think symbolically in that sense, it was really key.

Mike Berkowitz: It’s also key because Yascha and others have pointed out that it’s really in their second terms that authoritarian populists start to really undermine democracy. And so we saw plenty of bad things in Trump’s first term, but I would have been very worried about what we would see in the second. And yeah, we saw this with Hugo Chávez. We saw it with Vladimir Putin. The gloves come off after you get reelected. And so I think that’s another reason why I’m very pleased to see that. I think it mattered a lot for democracy. That said, I think we shouldn’t be sanguine about this.

Mike Berkowitz: There was some really interesting but disturbing research that came out in 2018 in a paper by Rachel Kleinfeld and David Solimini called What Comes Next? Lessons for the Recovery of Liberal Democracy. And one of the key headlines there was that recovery from an authoritarian populist can take a really long time, decades. And that often the leaders who are elected right after them face just such immense challenges that they become very unpopular and that leads to cycles that make it not a clean break, it gets very messy.

Mike Berkowitz: So whatever one’s assessment of Joe Biden and how he’s doing so far — and I would say from my vantage point that he has done pretty well — I’m worried about the set of challenges that he faces. I would have said that even if COVID hadn’t added so much more to his plate and the racial justice reckoning added so much more to his plate. Just having to dig out from four years of an authoritarian populist is really difficult. And so there’s a lot of challenges that we still have to face that mean that I think we should continue to be very vigilant and committed to these issues.

Robert Wiblin: I find it interesting that you are really focusing on the civil society aspect. I feel like that’s one area where Trump didn’t seem to matter, like he hasn’t managed to gag the press. It seems like nonprofits, political groups, are more vocal than ever. It’s not as if there’s any lack of opposition to Trump and his views. And to be honest, I’m not even sure how much they made a sincere effort to do things that would violate the First Amendment. Yeah. What worries you about decay in civil society? To me it seems reasonably healthy at the moment.

Mike Berkowitz: Yeah, I think I agree with your point. I think there is a lot that we were concerned that the administration would do on the civil society front, in part because I think Donald Trump and all of the forces that we’re experiencing in the United States are part of a global trend of authoritarian populism that’s manifesting in many countries, including of course, in some ways in the U.K. and India and the Philippines, Hungary, Poland. So there is a trend here and in many of those countries and others we see what’s called ‘closing space.’ We see greater restrictions on civil society. And we haven’t seen a lot of that in the United States.

Mike Berkowitz: Some of that I think is a little bit of a fluke of Donald Trump, which is that Donald Trump in my estimation was a little bit lazy. He wasn’t really committed in the ways that I worry about the next demagogic leader in the United States. He wasn’t really committed to the agenda of undermining democracy with quite the verve that he could have been. He was almost instinctively authoritarian, as others have said. And so they didn’t go nearly as far as I worried that they could have. That said, there were some attempts, for instance, to limit the ability of groups to organize on national land. Some restrictions in terms of free speech. And certainly a lot of rhetorical elements that I think made it really clear how the former president felt about certain communities and civil society organizations and efforts. So it was rhetorically pretty bad, I would say, with some intermittent attempts to restrict rights, but by and large, it wasn’t nearly as bad as it could have been.

Robert Wiblin: How much do you worry about lack of interest in democratic principles among people on the left and the progressive movement or centrists as well, I guess? To what extent does this cover the political spectrum?

Mike Berkowitz: Yeah. This is where I think it’s useful to understand the term liberal democracy. To cite Yascha Mounk again, in his book The People vs. Democracy, he really pulls these two concepts that go together — and that make up what we think of as democracy in places like the United States and the U.K. — he pulls these two concepts apart. So if we take democracy, democracy is about participation in the electoral and decision-making processes by the people. And of course, in the United States, we’re actually a representative democracy or a republic, so our participation as people is mediated through elected representatives. But the liberalism part is about a set of commitments to principles like freedom of speech, the rule of law, separation of powers, individual rights. And it’s that piece where I think the left can slip a bit. I don’t see the left slipping on its commitment to democracy.

Mike Berkowitz: I think many of us on the left would like to see more democracy, more participation in politics of course. But the liberalism piece is where I think there are more challenges. And I don’t want to say that these are symmetric in any way. I think that the challenges from the right to both sides of liberalism and democracy are much greater, but I do worry about some of the things that we see on the left. I don’t love the term ‘cancel culture,’ but I think there is clearly something happening in progressive spaces and in spaces that are heavily influenced by progressive voices, that whatever the motivations and intentions — and I tend to think that those motivations and intentions are quite good in trying to actually create a better society — that there are ways in which we are moving away from some of the commitments to small-l liberalism that I think are really fundamental to the kind of government and the kind of system of norms and values that I’d like to see the United States continue to be committed to. So I do worry about that.

Robert Wiblin: Do you think Trump did basically everything that he was able to do to try to undermine the election result and remain in power? Or do you think to some extent we got lucky that he didn’t go further and perhaps the effort wasn’t quite as sincere as it might have looked on the surface?

Mike Berkowitz: Yeah. I’m torn on this question, because I think on the one hand, he went pretty far. But he went pretty far without violating any laws. Maybe one could quibble about that point a little bit. But he didn’t try to overturn the results of any of the judicial decisions, the large majority of them in the post-election environment, which didn’t go his way, some in the pre-election environment, many that didn’t go his way. That was a thing that people were worried about. He wasn’t able to mobilize law enforcement. We were really concerned about what he might do with DHS. We saw a version of this in Portland last summer and fall and I think there was a lot of concern that we would see a kind of similar mobilization of law enforcement communities that he had a bit more sway over. There wasn’t a lot of real concern that the military was going to do anything.

Mike Berkowitz: As far as we understand, he didn’t try to go as far as we worried that he might in that regard, but he also continues to contest at least rhetorically the outcome of the election and he led that all the way up to the certification in Congress. And again, we’ve talked about what that resulted in in the halls of Congress on January 6th, which he was stoking that very day until some of his advisors somewhat haphazardly convinced him to walk it back a bit. So did we get lucky? Maybe. There may be, as I was alluding to earlier, a version of laziness that helped out here, but I would say at the end of the day he was pretty much constrained and stayed within those constraints by law.

Mike Berkowitz: And it’s also worth noting that the Republican actors who he was trying to pressure, people like Brad Raffensperger and Brian Kemp in Georgia and Mike Pence, the line that they wouldn’t cross either was what their legal obligations were. So what worries me going forward here is when those legal obligations change. And we were talking earlier about the voting rights, laws that are being rolled back and many of the bills to really restrict voter access that’s happening at the state level. The other things that those bills are doing is trying to shift power to more partisan bodies. So there was this Georgia bill that passed last week, I believe it was, that takes away some of the powers of the Georgia Secretary of State. Well, why is that the case? It’s clearly retribution for Brad Raffensperger. It also clearly will mean that next time around when it’s Donald Trump or someone else trying to overturn the result of the election, I think they might get much farther than Donald Trump did in 2020.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah, I think we have to be incredibly thankful to people like Raffensperger. People in positions like his basically risked their lives, their careers, or took on enormous amounts of abuse in order to in effect ensure that politicians who they incredibly strongly disagree with on the issues were elected, because they thought it was their legal and moral and patriotic obligation. And it is really quite terrifying that there are efforts to oust people like that so that next time the people who are making these calls about whether to throw the U.S. into a constitutional crisis are going to be far more partisan and might just not be willing to stand up to that. Yeah. You can imagine in 2024, if you have a very close election and there’s all of these bodies and individuals who are partisan actors potentially casting doubt or throwing out the results of the election, in effect, where they could lead things.

Mike Berkowitz: Yeah. And I mean, I think this really illustrates the distinction between norms and laws, which is a problem we really came to realize throughout the Trump presidency. That so many of the things that we thought were law were actually just custom. And once you had someone who didn’t feel any obligation to abide by those customs, they went away. You apply that lens to the actions that we saw by Republican politicians in particular, in the aftermath of the 2020 election, and it’s quite interesting because, as I said, folks who were asked to violate the law didn’t do it. People who could violate long-standing norms without breaking laws, many of them did. And that’s how I think about the actions of the 150 or so members of Congress who voted not to accept the results of particular state elections. There was no consequence to them doing that.

Mike Berkowitz: And so I don’t know what the right thing is in this particular realm going forward, but one of the things that I do think is going to be really important for protecting American democracy going forward is to do more hardening of norms into laws so that we give actors in the system a bit less opportunity to violate customs that are there for good reason. Some of them are not. I’m all for re-imagining our norms, but some of them are really important. They are what actually upholds our system. So we need some combination of the moral courage that we saw exhibited by some Republican politicians in particular, this last cycle, who did, as you said, put their political careers, sometimes their lives and their family’s lives in some jeopardy. On the other hand, they did it because it was their job and it was the law. And I think the more hardening of norms that we can do within reason, the more people will be able to take those politically courageous stances.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. So I guess it is hard to know exactly what Republican members of Congress think. But I imagine that many who voted to effectively ignore the election results or to throw them out, in fact, didn’t believe that the election was fraudulent and were doing it just to save their skin and to avoid getting primaried in future elections.

Improving incentives for representatives [00:30:55]

Robert Wiblin: Is there anything that we can do to improve the incentives that senators and congresspeople face so that they are less likely… Because, I mean, it does seem possible that in a future election… What if you do end up with a really unhinged elected group in the House of Representatives and they decide that they don’t want to lose their seats, and so they’re going to vote to overturn the election results? It’s pretty terrifying.

Mike Berkowitz: So this is where I think both political leadership and political structures and incentives really do matter. On the one hand, one can look at leadership here and say, if Donald Trump hadn’t been making the claim and pushing others to make the claim that the election was stolen, we wouldn’t have seen hardly any of the actors who abided by that falsehood do so last year. I just really don’t think we would have seen that. Donald Trump’s popularity and power within the Republican Party also forced their hand to some extent. Again, I think it was the wrong calculus on many levels, but he really did box many Republican politicians in by taking that position.

Mike Berkowitz: But to your point, this is also where incentives and structures really do matter. And I think we’ve realized that even the best politicians, even the most courageous and moral, and ethical ones are working within a system that has particular incentives to it. And so there’s a lot of political reform efforts that are out there right now that are really looking at this question. For instance, there was just a report that came out, I believe it was called The Primary Problem by a group called Unite America, just out this week, and they really talk about the problem of partisan primaries, where you have the most ideologically committed voters within a party turn out in what’s almost always a low-turnout election. This is the way primary elections are. And the incentives, then, if you are trying to win a partisan primary, are to be more partisan. You’re trying to get your base.

Mike Berkowitz: And so therefore you wind up with more ideologically extreme candidates in general elections. And again, because people largely vote based on the hat that they wear, the R or the D in American democracy next to a candidate’s name, it almost doesn’t matter how extreme a candidate is in many districts because those districts are so safe, they’re going to win regardless. So I do think political reforms are important here. I’m a little agnostic personally about which ones, we could talk more about this, but I do think some reforms to the system are really key to get at the structures there as well.

Robert Wiblin: The primary thing is very notable. As far as I know, I think all of the Republicans who voted to convict Trump either were retiring or weren’t going to face a primary election anytime soon. I come from Australia and now live in the U.K., which are two countries where largely we don’t have political primaries. Parties appoint candidates. And in general, they tend to choose candidates who are pretty close to the center of the seats that they’re running for, because that makes them most likely to get elected in the party, and therefore most likely to hold power.

Robert Wiblin: So it creates this kind of centrist tendency to not have a small minority of 5% or 10% of people in a seat choosing who the candidates are on either extreme. The primary thing is a little bit harder in the U.S. Because of your first-past-the-post system, which Australia doesn’t have, there’s an incredibly strong tendency to have only two parties, which then means that whoever would happen to end up controlling one of those two parties could then potentially have very outsized influence over who gets selected, and that would have a degree of arbitrariness to it. Where in Australia, and to some extent the U.K., because it’s a more multi-party system, it’s possible to potentially get rid of a party that’s not representative in a way that’s very hard in the U.S.

Robert Wiblin: But I suppose I would love to see a reduction in the frequency, I suppose, of these kinds of political primaries. Well, one option might be in the House of Representatives to just move to a cycle of only… I mean, the House of Representatives is very unusual in the modern world for having everyone elected every two years, that’s very peculiar. I almost don’t know a country that has a national government reelected that frequently. And potentially you could move to a cycle where the primaries only occur every four or six years.

Mike Berkowitz: I think there’s a lot of ways that we could reform the House of Representatives, or elections there, as well as elections throughout the system. I mean, one reason that I’m a bit agnostic on which reforms, is I think number one, there are some very, very smart people who I trust, who are proponents for different reforms. And whether it’s ranked-choice voting or having a multi-party system, or something along the lines of final-five voting… I look at these very smart people who I trust and say, “I don’t know what the right answer is here, and therefore I’m personally not going to be a proponent for one over the other. I think we should try them.”

Mike Berkowitz: We have this federal system in the United States that gives us the ability to do things at the state level. And in fact, our elections, even our national elections, are actually state elections. And so there’s a lot we can do to actually test these reforms and see what works, and I think we should do that. I also think that we need to recognize that any reform is going to have unintended consequences, and so we need to have a lot of humility as we think about these possibilities.

Mike Berkowitz: And to your point about the U.K. and Australia, and obviously this goes for many other countries as well, there are other systems of government out there that are also facing real challenges from authoritarian populism, for instance. And so this is where I think it’s just an incredibly complex problem to think about. We need to change some of the structures and incentives in the United States, no doubt, and we also need to recognize that even some of the systems that we might want to emulate abroad are also facing real legitimacy crises from authoritarian populism around the world. And so there’s no silver bullet solutions to these challenges.

Robert Wiblin: One thing that a lot of people, including me, were worried about last year was that there would be large-scale voter intimidation efforts at polling places. And it seems like that basically just didn’t happen at all, despite I guess, meaningful threats that people were making to go and do this. Why do you think that that was? And is there a lesson here about… It’s very easy to get hyperbolic and worry about absolutely everything, but sometimes we do have fears that just are not realized, like Trump not really doing that much to restrict the media from criticizing him. How do we avoid worrying about mirage problems?

Mike Berkowitz: Well, so one thing I don’t think we should do is look at the 2020 election for instance, and say, “Well, because we didn’t see the kinds of voter intimidation problems on election day that we were expecting, at least not the magnitude, there certainly were some, that therefore we shouldn’t have been alarmed.” I mean, one could expand that to all sorts of things related to the functioning of the 2020 election. The thing that I was really worried about was that broadly speaking there would be chaos, that there would be intimidation and violence at polling places, that people would be so confused by all of the different ways that they could vote, by the restriction of polling places…

Mike Berkowitz: There were a lot of changes to election law last year, and of course we were voting during a pandemic. So we were really worried about chaos. And I refer to the 2020 election itself as a civic miracle, because most of the concerns that we had did not come to pass. but I don’t look at that and say, “Well, we were overly alarmist.” I look at it and say we were properly alarmist, and we invested in lots of different areas within philanthropy and civil society to really try to prevent some of those worst-case scenarios from happening.

Mike Berkowitz: And there were lots of people in the system, from really responsible media actors, to civil society groups and philanthropists, to election administrators who I think were really the heroes of 2020, to people who signed up to be poll workers. I mean, there were a lot of people who contributed, of course, to the smooth functioning of the election. But I think that at the end of the day, it was a combination of those collective efforts, number one. Number two, I think at the end of the day, Donald Trump was just such a polarizing figure that he really drove an incredible amount of turnout. I mean, it happened on the right as well as the left, but I think there were a lot of people who just weren’t going to stay home when Donald Trump was on the ballot, and so they overcame a lot of barriers that we might’ve seen have more of an impact otherwise.

Mike Berkowitz: And then finally, I just think there were so many changes to voting laws that made it easier for people to participate, that they just were going to show up and do it. And they were basically facilitated in participating by a lot of these rules that made it easier for them to do so. But why we didn’t see more intimidation on election day is a little bit hard to say. I guess that my only other supposition here is that there were a lot of attempts on the right prior to the election itself, primarily using legal means to restrict voting rights and restrict voting access, many of those attempts were thwarted in the courts.

Mike Berkowitz: And so it may be that that was the primary vehicle, because it had some legitimacy behind it to try to prevent voters from turning out in large numbers. And that come election day, the kinds of things, even in this crazy political environment that may have been acceptable in some places in say the 1960s, just really weren’t acceptable now, and so we didn’t see those kinds of attempts at the scale that we worried about. But it’s certainly a confusing picture. All I know is that we were right to be alarmed, and I think that alarm certainly contributed to a good outcome.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah, it is interesting that despite the fact that… Maybe because of the fact that people are so concerned about voting access now it’s possible that actually voting access is maybe as good as it’s ever been, because people maybe underestimate just how much voter suppression and just how difficult it could be to vote, especially for some people in their 50s and 60s. And in fact, the trend has mostly been in the right direction over a long period of time.

Robert Wiblin: With the benefit of hindsight, are there any specific actions that you wish people had taken back in 2015 and 2016 in order to try to curtail this problem before it became worse?

Mike Berkowitz: Yeah. I really wish the Republican Party had taken Donald Trump more seriously as a candidate. I think they could have done that at multiple stages along the way, including when it became clear that he was going to be the nominee. I try not to make too many analogies to Nazi Germany, but I think there is a really interesting analogy here from the early 1930s where von Papen convinces von Hindenburg to appoint Hitler as chancellor and himself as vice chancellor, and von Papen thinks that he’s going to be able to control Hitler, and of course he’s not able to.

Mike Berkowitz: And I do think there’s an analogy that’s worth understanding here in terms of the Republican Party’s — at least in 2015 and 2016 — orientation towards Donald Trump. Even though I think there was a period of time where they simply just didn’t take him seriously as a candidate, even once they came to take him seriously, and when he became the nominee of the party, I think the reigning thinking at that point was, “We’ll be able to control this guy.” And the lesson for me is you can’t control someone who does not feel restrained by democratic norms and values. And I think it almost always comes back to bite you when you try to do it. Instead what happens of course is Donald Trump takes over the Republican Party.

Mike Berkowitz: And again, I don’t purport to have any idea of what’s going on in the heads of Republican leaders right now. But I have to think that there was a point at which they really saw that as a bad thing, as not what they wanted for their party. And now even if they might say that behind closed doors, they’re certainly not doing anything to counter Trump’s supremacy within the Republican Party.

Mike Berkowitz: So that’s the only thing I could imagine. I really don’t know that there’s much outside of the conservative or Republican coalition in 2015 and 2016 that could really have been done differently. I think this is the kind of thing that was up to the right to do well, and I think they missed the critical opportunity to keep Trump and Trumpism contained. As, by the way, they had done not completely effectively, but pretty effectively for many decades prior to that. It’s not as if the Trumpist strain, even though it has particular manifestations in this political era, but it’s not as if there wasn’t that kind of anti-elitist populist thread with lots of white supremacy and other elements built into it, that existed within the Republican coalition. But this is part of the point of actually having political parties, is that they can restrain and moderate the more extreme fringes of their coalitions. It’s really when you let those extreme voices take over that you have a problem. So that’s what I wish had been done differently in 2015 and 2016.

Signs of a loss of confidence in American democratic institutions [00:44:58]

Robert Wiblin: Okay, let’s zoom out from just the Trump era and think about what can be done to shore up the U.S. system of government more generally. When you look at all of the evidence out there, what are the strongest signs, I guess, other than these kinds of topical events, that there are underlying social problems and a loss of confidence, loss of robustness in American democratic institutions?

Mike Berkowitz: So I think there’s a number of ways to look at this. And my theory of the case is actually a metatheory, which is that I think the effort to protect democracy, to sustain it over the long term, is a wicked problem, which is to say a deeply, deeply complex challenge that can be articulated in many different ways, by many different smart people, and therefore can have lots of different solutions. But when I look out at the set of factors that we’re facing right now, here’s what I see. And this is one of the reasons that I tend not to think that there’s one or even two solutions that are just going to solve everything.

Mike Berkowitz: I mean, we have had a dramatic decline in civic education and learning in this country. It used to be part of curricula throughout schooling, certainly public schooling, and that’s really gone away, and now there are attempts to revive it. We have seen the decline of local news over the last 20, 30, 40 years, local newspapers which were major sources of information for people and connected them to things that were happening in their communities, that were happening with their local elected representatives, they’ve just been decimated by changes in media. That’s a real problem in terms of the kinds of information that people get in their connection and their sense of connection and agency in American democracy. That obviously runs parallel with a rise in disinformation, which has always been a problem. But what we are facing now is really rapidly increasing speed when it comes to disinformation, it travels much more quickly online. And then we have partisan broadcast channels, talk radio, YouTube channels, obviously television stations like Newsmax, OAN, Fox News that are really spreading this much more widely.

Mike Berkowitz: We have a new form of polarization in our politics which we refer to as toxic polarization, where we’re not just fighting anymore on the issues. It’s not just that we have really different views about abortion, or gun control, or democracy, it’s that our identities are becoming stacked on top of our political differences. And so we have these really tribal differences. We no longer see one another as part of a common project. And so it’s no longer about how we can find compromise. It’s about how we can defeat one another. And that’s a really challenging situation.

Mike Berkowitz: As we talked about earlier, we have bad political incentive structures, and we also have the diversification of the United States and other countries, which is causing a white identity backlash. So we have all of these things happening at the same time, whether they are probably… As I would say they are all intertwined causally, but I don’t know that we can really tease apart a clean path where one simply affects the other, affects the other. I don’t think that they’re wholly distinct from one another. To me, they’re all jumbled up together as challenges, and they’re just a manifestation of the complexity of the challenge and the reason why we need to understand that there is no silver bullet solution to this problem and that it’s going to take a long time to solve. This is not the kind of thing that you fix in one election or even one electoral cycle, it’s going to take many decades to get this right.

Mike Berkowitz: And then also, even as we, and by we I mean people in civil society or in philanthropy, have our particular focus areas, we need to understand the work that we’re doing in a broader context. So folks who are working on local journalism need to see themselves as part of a broader effort to revive American democracy. Likewise, with the political reformers who have their chosen or preferred reforms, we all need to see ourselves as part of a broader effort here.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah, it’s interesting, to prepare for this interview I was just taking a quick look at some political polling in the U.S. and other countries, seeing how committed people are to liberal democratic values. I guess it was slightly heartening to see that, I guess, just the great majority of Americans in polling centers say that it’s very important to have regular elections, very important to have a largely free press, very important to have religious freedom, very important to have the rule of law. But I guess there are other trends where you see just big declines in trust in political institutions, or indeed across basically all institutions in the study. Except, interestingly, the military. But the media, the courts, Congress, the Senate, just across the board, compared to the 1950s, people just have much less trust in their competence and their truthfulness.

Mike Berkowitz: Libraries are the one other institution aside from the military that still has pretty high levels of trust.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. And as you’re saying, there are just big increases in people thinking that members of the other party are bad people. That used to be a fairly minority view and is now a very mainstream view, which is pretty troubling. So it’s an interesting mixed bag. I’ve seen so many explanations that people have put forward for this trend over the last five years. Some people talk about how the internet is radicalizing people perhaps, or allowing people to end up having unusual ideologies that previously would have been cut out of the mainstream, some people talk about increases in economic inequality or dissatisfaction with the job market and wages, so some people have an economic theory.

Robert Wiblin: Some people think it’s a cultural backlash to progressivism and immigration and culture changes, challenges to masculinity and traditional values…that you’re getting a backlash to that. It seems like we almost have too many explanations and I don’t really have a very strong view one way or the other on which of these underlying trends is causing this political change. Do you, and maybe your colleagues, take any position on this or are you maybe fairly agnostic on what are the underlying social drivers?

Mike Berkowitz: Everyone wants to understand these challenges. And I think those who come to firm conclusions about them at this point are probably jumping the gun a bit. I mean, I just think we don’t know. I think it is clear that all of those trends are factors in one way or another. Part of the challenge of trying to figure this out is really looking at both the domestic and the global context, as we were referring to earlier, because there are particular things that we see here.

Mike Berkowitz: So for instance, when you talk about immigration and the cultural backlash there, that is certainly a factor in the United States, and yet you see similar dynamics playing out in a place like Poland, which doesn’t really have an immigration challenge, it is a very homogenous country, and yet some of the same kind of racist or nativist sentiments are part of the populism that is taking place there. And so I just think we don’t know enough yet to know why these things are happening in the ways that they are, how this stew of issues actually is manifesting, what are the drivers, what are the symptoms, what are the underlying causes. We just don’t know enough, and I don’t know that we need to.

Mike Berkowitz: I mean, I guess this is where I come out on it. It’s not that we shouldn’t aspire to get more clarity about it over time, I do think we should. There’s plenty of research going on in that regard, and I think it is very, very, very worthy, but I also think we need to avoid a reductionist impulse to really try to figure out, is it culture, is it economics? I just think those are too simplistic. However they come out in the wash, those bifurcated ways of understanding the problem are just going to be too simplistic. And so I’m quite comfortable saying that those are all part of the problem. And I think there are very smart people who would say this one over that one, and there’s another person who would say that one over this one. And I think that’s just a… Again, it’s a manifestation of the wickedness of the challenge, we just don’t know.

Robert Wiblin: One other big theory I forgot to list there is The Big Sort‘s theory that you’re getting a big… The people with particular personality and education characteristics are sorting into the same counties and then are meeting one another, and then people who have a very different personality are all sorted into rural areas, and that causes polarization because people just don’t meet in their social circles people who are different, and there’s fewer cross-cutting pressures of you might meet a conservative at church, but like them, even though you have different politics, that kind of thing.

Robert Wiblin: I just don’t really have a strong view here because it seems like the empirical picture is extremely complicated, you can find both evidence supporting and contradicting or in tension with all of these theories. And so it does seem like we have to proceed thinking, well, all of these things could be playing into it and we’re not going to get a really clear answer anytime soon. Social scientists might figure this out sometime down the road, but it’s not easy.

Most valuable political reforms [00:54:39]

Robert Wiblin: Given all that, what do you think are the most important levers to push on to try to shore up the political situation in the United States?

Mike Berkowitz: So I would say a couple of things here. One, as we talked about, I think, political reforms are really important. I mean, I think we have to change some of the incentive structures and see what happens. It was noted that Lisa Murkowski, a Republican senator from Alaska, was the first senator on the right to come out in favor of Donald Trump’s impeachment after January 6th. Well, that also happened after Alaska had passed a set of voting reforms, including final-four voting, where there were no longer going to be partisan primaries, there will be an open primary and the top four vote getters will move on to the general election and there will be ranked-choice voting. So you’ll get to list your preferences among the final four candidates. And that is thought to enable more candidates to appeal to a wider segment of the population. So it was noted that this reform may have played a significant role in Murkowski being able to come out as quickly as she did and as forcefully as she did on Donald Trump’s impeachment. So political reforms I think are key.

Mike Berkowitz: Second is I really do think we need to revitalize local journalism. We have so little accountability right now among elected officials in Washington DC, or in state houses. We forget sometimes we used to have entire delegations of reporters covering the actions of elected representatives. With the decimation of local journalism, that has gone away. We also just have less connection and knowledge about issues within local communities.

Mike Berkowitz: I was talking with someone the other day who made the observation that we’re much more likely now to know what’s happening in somebody else’s community than we are in our own, because in somebody else’s community, maybe there was something that was just so shocking that it made the national news. And so we’re focused in all the wrong places with our own kind of civic energies in that regard. And it’s impossible to imagine how we really combat disinformation or get to any shared fact base — which we need in a functioning democracy — without a much healthier, or a much more robust and rebuilt set of local journalism institutions. Newspapers, online publications, et cetera.

Mike Berkowitz: And finally, I think in order to overcome toxic polarization, we need to build social cohesion in this country. When I talk about social cohesion, I don’t mean just how we can all just get along better. That’s an overly simplistic view of what I think social cohesion should mean. It’s actually, how can we disagree while still seeing each other as part of a common project and part of a common political community? How do we still see each other as human, despite our political differences?

Mike Berkowitz: And right now we’re losing that capability and it’s causing a lot of the challenges that we’re seeing, including an increase in extremism and violence. And I think it contributes to the rise of authoritarian populism. As I said earlier, tribal loyalties are superseding the commitment to democracy. So this is an area of work that I think needs much more attention from philanthropy and from society at large. And it’s hard for me to imagine at the civic and cultural level, how we can continue to function if in fact we are in such warring tribes. And I do worry about the warring piece of that continuing to not just be in name or name-calling only, but really in continued acts of political violence.

Robert Wiblin: Okay, so we had three there. The first one was, I guess, changing things like voting methods and how people are appointed and what incentives they face as politicians. The second one was local journalism and the third one was building social cohesion and getting people to have some more fond feelings towards people who they disagree with on politics. Maybe let’s go through those one by one.

Robert Wiblin: What do you think are some of the most valuable structural changes that we could make to the political system? I guess you mentioned earlier that there’s lots of smart people who disagree on these questions, but are there any options that you feel more positive about than others?

Mike Berkowitz: One of the most promising ones on the voting front, for instance, is automatic voter registration. It’s a little bit odd and probably not coincidental in the United States that when a boy turns 18, he’s automatically drafted into the selective service. That happens without him doing anything, and means he could be on call for military service at some point. But one has to proactively register to vote to avail oneself of that right in our system. I should note, it’s not a constitutional right, there is no right to vote in the U.S. constitution, which I think is also a challenge here.

Mike Berkowitz: And so automatic voter registration is at least one I think quite popular reform — not just on the left, but it actually has some adherence across the political spectrum. It basically says that when you go to get a driver’s license, for instance, you’re automatically enrolled to vote. So that’s a really, really key reform on the voting rights front. I do think expanding the ability to vote by mail is really key, I think we saw a lot of that.