Transcript

Cold open [00:00:00]

Peter Godfrey-Smith: I like life very much, and have no interest in dying in the near future. But I do look at the whole system, and at the role of bodies like mine, ours, in the whole system, and I think it’s fine to pass in and out of existence. It makes sense that we will. It’s something that I think is very hard for it not to happen.

Once we think of our lives in a kind of grounded way, and also think of ourselves as, in a sense, sort of taking up slots that can be filled by others in the future, other living beings, then the coming into existence and going out of existence seems to me to be… It’s not that I’ll welcome it when the day comes, I don’t think. But looking at the whole. I think it’s fine as a whole, you know? I’m fine with that general picture.

Luisa’s intro [00:00:57]

Luisa Rodriguez: Hi listeners. This is Luisa Rodriguez, one of the hosts of The 80,000 Hours Podcast.

Today’s episode was a really fun one for me. Peter Godfrey-Smith is the author of one my favourite books: Other Minds, which explores the origins of consciousness and intelligence through the lens of octopuses, so I was super excited to get the chance to talk to him about his new book, Life on Earth.

It’s a short episode, but we managed to cover a lot of ground.

- We debated the moral dilemmas around wild animal suffering: whether Peter thinks wild animals’ lives are, on balance, good or bad, and when, if ever, we should intervene in them.

- Peter shared why he doesn’t think we can or should avoid death by uploading human minds.

- And he explained why the evolutionary transition from sea to land was key to enabling human-like intelligence — and why we should expect to see that in extraterrestrial life too.

- And a bunch more.

I hope you enjoy our conversation as much as I did. Without further ado, here’s Peter Godfrey-Smith.

The interview begins [00:02:12]

Luisa Rodriguez: Today I’m speaking with Peter Godfrey-Smith. Peter is a professor in the School of History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Sydney, and the author of seven books — including Metazoa: Animal Life and the Birth of the Mind and Other Minds: The Octopus, the Sea, and the Deep Origins of Consciousness, which is one of my favourite books.

We’re here to talk about the recently released third book in this trilogy, Living on Earth: Forests, Corals, Consciousness, and the Making of the World. Thanks for coming on the podcast, Peter.

Peter Godfrey-Smith: Thanks for having me on.

Luisa Rodriguez: Living on Earth covers so many topics. How would you describe the unifying theme or arc of the book?

Peter Godfrey-Smith: The central idea, the original point of the book, was to do something that complemented the other two books in the trilogy. The other two books were about the mind as a product, something that’s come to exist through various processes. And there’s another side to the picture, which is the mind as cause — as making things happen, as changing how events go in the world.

That was the starting point: the idea of having a couple of books about where minds came from, how they came to exist, and a third book about what minds do once they’re here.

Now, when I say “mind,” the natural way to think about that topic is to think about the mind as an aspect of living activity. So the book is really about the causal role of living activity in general — with animals, animal action, nervous systems, thoughts, and consciousness as one component of living activity, and one especially efficacious form of that activity.

Wild animal suffering and rewilding [00:04:09]

Luisa Rodriguez: Nice, thanks for that. If you’re up for it, I’d like to start with a chapter in the book on wild nature, which was one of the chapters I found most evocative. One of the arguments you make in that chapter is you want to see habitat degradation addressed and more resources spent on habitat preservation. As part of that discussion, you explain your own thinking on whether it’s actually good for wild animals to exist for their own sakes, given all the potential for suffering in nature.

You and I come out on pretty different sides of this question, so I thought it’d be interesting, from my perspective, to talk through some of those differences. Could you start by explaining where you come out on it?

Peter Godfrey-Smith: Sure. And this was a hard topic for me. This is one where I think the text reflects the difficulty I found in thinking about this.

In the chapter about some other ethical and policy issues, the one before that, I already moved a little way away from some standard positions and theories in moral philosophy. I did not accept a utilitarian outlook, but did accept something that’s relevantly similar, a kind of a view based on the importance of individual welfare in animal lives, especially the lives under our control.

And then in the chapter you’re referring to, then one has to grapple with the question: What should we do if we think that the welfare of most wild animals is not that great? Does that mean we should intervene to transform that aspect of nature, and either eradicate species where we think the general profile will be one that’s negative from an experiential point of view? Or perhaps transform the animals themselves by some kind of manipulation or selective breeding to reduce predation, to produce population booms and busts and things like that?

I came out against those kinds of views and in favour of a programme of rewilding, of habitat preservation, of keeping wild nature — including all of the contrasts between negative and positive aspects of life.

To some extent this reflects a belief, or a suspicion at least, that there’s more positive experience in wild animal lives than some people discuss. You get a lot of discussions that emphasise predation, the “red in tooth and claw” side, and that can become almost obsessive in some discussions. The fact that the animals in question also get to lie in the sun and have companionship and have a lot of other positive experiences, that sometimes gets left to the side. So as a first move, I wanted to just put back into the foreground positive animal experiences in wild nature.

Then it’s natural to say, let’s try to do some accounting: let’s try to work out whether the positive outweighs the negative. And here I really ran into some difficulties, because I came to think that the accounting is more problematic — even in principle, let alone in practice — than I had thought at the start of this.

This has to do with the application to animal lives something that I think we’re pretty familiar with in human lives: the fact that a person might have a difficult life in many ways — with many hours, days, years spent in difficult circumstances — but there are such things as experiences and events and achievements that redeem the difficult stages, such that a person reaching the end of their life might say, “I wouldn’t change a thing. It was hard for years, but in the end I did something that I think is completely valuable, worthwhile, and redemptive in relation to those difficult experiences.”

Now, in the human case, I take it this is not an unfamiliar thought. It would be mistaken to give a kind of hour-by-hour accounting. You know, “I had +4 level of experience for this hour, then I had -2 for the next hour, and then I had -1” — and you sort of sum to try to work out the total.

That would not be appropriate in the human case, and I came to think that something like that will be applicable in some of the animal cases as well. That, in the case of some animals — and here we’re talking probably about mammals and birds and neurally complex animals for the most part; I don’t know how far I’d extend this argument — there are achievements, there are experiences, there are things that can be done in the face of difficulty that might be seen as having the same kind of redemptive role, as casting into a different light the difficult events that led up to it.

The example I use in this part of the book is watching some birds, not far from where I am right now, actually, successfully raising some young, fighting off a couple of rather aggressive parrots of another species that wanted to fight them, prevailing against difficult odds — and doing so in a way that was so wholly successful. It seemed to me that if you wanted to do an accounting of how things had gone for those birds, you would not want to do the naive thing of just counting up difficult and less-difficult hours. There’s something special about what’s achieved at the end of that process.

OK, so idea number one: I had a kind of welfarist view about some animal ethics issues. A welfarist approach to some questions about wild nature is very hard to apply, because of the way that events become meaningful in the light of other events — I think not only for humans, but potentially for other animals as well.

And that whole line of thought orients me towards an emphasis on a richness of two kinds in wild animal lives. Firstly, what we’ve just been talking about: the sort of being in the fight and having it be possible to achieve things that redeem difficult periods.

There’s that side, and there’s also a side that’s in some ways quite far from standard moral philosophy options here, where we look at this whole structure, the tree-shaped historical procession of animal life, of animal evolution, including ourselves within it, and there’s a kind of… I mean, we have wound up with the capacity to make choices that affect the whole. We have wound up, like it or not, having a kind of steward-like role here.

And there’s a kind of ingratitude in allowing the richness to be destroyed. There’s a kind of, I think, unwillingness to recognise kinship when we allow other species to sort of decline and go extinct. There’s an orientation towards our relation to the whole that I think pushes towards the benefits of preservation and rewilding and that kind of option.

OK, now I’ve said lots of stuff, so now I’m very curious as to where we depart on these questions.

Luisa Rodriguez: Yeah, and I’m so grateful to you for being up for it, because I really do think this is a really important question given the scale of wild animal life, and one that people have these extremely different views on.

So there were a few steps. I think the first step where we depart might even be at the point where, in thinking about the human experience and how valuable richness is, here I feel genuinely very torn. Part of me does have this sense that the hard things I’ve experienced do get kind of reinterpreted over time as valuable, as leading to growth, as adding a diversity of experience to my life that I value.

On the other hand, I hope to have children. If I have a child, I wouldn’t wish the depression that I’ve experienced on them. I would love actually just for them to be in great health, for them to go through life without the hardship that to some extent I, but much more so other people, experience.

And so I feel at least sympathetic to the idea that we have this psychological mechanism that encourages us to do kind of sensemaking in a way that is maybe beneficial, in ways that are a bit complex, but that don’t actually reflect the true goodness and badness of our experience. So maybe we’re telling these stories, we’re reframing things, but that’s kind of instrumentally valuable in itself, and so we do it. But it doesn’t actually mean that, on the whole, those experiences were all good and worth having and we’re better off for them.

Do you feel sympathetic to that at all?

Peter Godfrey-Smith: It’s not that we should look back on the bad parts and say, “No, actually that was good.” The bad stuff can be bad. But with respect to at least some of the negative elements, the bad side arises as part of a struggle, as part of an attempt to pursue projects that are intrinsically contingent and difficult and risky and put lots of demands on us.

And then when things go wrong, it’s still that things went wrong; it’s not that I think we should find ways to reinterpret the genuinely bad stuff as straightforwardly good. I think that in some cases it does make sense to see it as being outweighed even by briefer periods of great significance that come downstream. To some extent, it’s the kind of naive, hour-by-hour accounting that I want to immediately push back on.

Now, one of the examples that you used of a negative experience is ill health, including depression. It’s hard to see something positive in that, even in the kind of context that I’m trying to put on the table here, because it’s debilitating. It makes it harder to pursue the stuff that might wind up leading to achievements that redeem and rebalance everything. There’s not much good that one can say, I take it, about depression.

Luisa Rodriguez: Right. OK. It sounds like we’re at least closer to a similar position there than I thought. I think neither of us think that the bad things are actually good. We might differ a bit in degree about how many bad things, and how they’re outweighed by the positive things that come about through culminations.

Peter Godfrey-Smith: I think one of the questions, which is a real point of possible disagreement, is how desirable it would be to flatten things out: to make everything predictably benign, to reduce the heights, but also reduce the strongly negative periods.

You mentioned the kind of hopes that you would have for your child. And if this isn’t pushing too hard, do you find yourself thinking, “I would be fine if everything was pretty flat, so long as it was flat in a positive way”? Or, “I would like there to be the challenges, the ups and downs, the complexity, the richness with its negative side”?

Luisa Rodriguez: Right. Yeah, it’s a great question. I think there is an extent to which I would wish for them some cutting off of the bottom and would take some cutting off of the top for them. I think that’s what you mean by flattening.

Peter Godfrey-Smith: Yeah, the compression step in sound engineering. And it’s not that I’m criticising that. I think this is a point at which one can probe and reflect on to what extent is reduction of variance desirable, and to what extent is it a kind of giving up of the valuable aspects of the struggle?

Luisa Rodriguez: Yeah. I guess it brings me to another potential point of disagreement, which is that ideally, I’d love to just cut off some of the bottom and not cut off the top end. And I at least think that there are ways to do that for wild animals — for example, trying to eliminate some of the worst, most painful diseases that wild animals suffer from. Do you think we disagree on things like that?

Peter Godfrey-Smith: Yeah, that’s a good case to think about. In this discussion, in the philosophical debates that I make contact with, it’s mostly predation that people contemplate intervening on, and also overproduction of young — you know, just producing countless thousands of young who’ve got no chance of making it.

Disease is a different kind of case. It’s hard to deny. It’s hard to see the downside, I must say. I mean, I think we’re talking about a very difficult, very far-fetched hypothetical scenario here, but that doesn’t really bother me.

It’s hard to see a downside in trying to reduce, just as it would be great to eliminate all kinds of viral diseases or greatly reduce their prevalence in human populations. Suppose we’re doing that, and it turned out that the method that we had come up with was readily extrapolatable, and would not be too hard to implement, and it would just reduce the viral burden on life in wild nature.

Now that you ask that, I find myself thinking that that’s not a bad idea.

Luisa Rodriguez: Not crazy. Yeah. I think in your book, you use the line, “One death will be replaced by another.” And that did move me a bit, until I was like, well, I would prefer some deaths over other deaths. I think this might be the clearest case for me: I would prefer to die a quick and more painless death than I would to die from a particularly painful disease. So maybe that is just looking more like a point of agreement for us.

Peter Godfrey-Smith: Well, hang on. The passage you mentioned is in a discussion of wild nature. And the way it came up was Jeff McMahan — who’s the philosopher who has written most extensively on the argument for intervening in predation, in particular in reducing the tendency wild animals have to attack and eat each other — he, at a certain point, has to acknowledge that when you make animal less likely to die from predation, you don’t make it less likely to die full stop. You just exchange one kind of death for another.

And I think that’s a really important next step: whenever one’s talking about eliminating death of one kind, you’re talking about substituting another kind. Now, a moment ago, you said a quick, painless death. I don’t know if many animals in wild nature get that. I think that’s a difficult thing to achieve.

Luisa Rodriguez: I agree. I think it was simplistic. I think what I mean is, I have to believe that there are better and worse deaths. And if we can think about that enough to be confident about what those rankings are like and eliminate some of the worst ones, I would just feel really good about that.

Peter Godfrey-Smith: Right. And the reason why I was somewhat moved by your introduction of disease here is I think that in many cases, as on the bad list for wild animals, I would rather be eaten by a crocodile or a shark than die of a lot of diseases. So predation deaths are not, in a lot of cases, harder, tougher, more unpleasant than the deaths that would replace them.

Luisa Rodriguez: Yeah. That’s exciting to me that we found some point of overlap.

Another angle is around whether we should allow for humans to expand and wild nature to contract. One argument that feels like it could potentially be compelling to me is: if I were a little soul floating out in the universe, and the Earth existed, and I could either be born as a human or I could be born a random wild animal — probably, to actually make progress on this, we should pick specific wild animals — but even if I just say a random wild animal, I’d rather be born as a human.

That fact makes me think we should feel OK about more humans existing at the expense or trading off against wild animals existing. What’s your reaction to that?

Peter Godfrey-Smith: This is a random human looking at the whole of human history, or now?

Luisa Rodriguez: That’s a good point. I do mean now. It’s true that I would not have preferred to be born into feudal Europe.

Peter Godfrey-Smith: Yeah. I would probably rather be a random wild… It’s not obvious to me, actually. Now, in some ways, this is, of course, an extremely unconstrained, all-over-the-place thought experiment.

Luisa Rodriguez: Absolutely.

Peter Godfrey-Smith: But I can’t just push it away, because at several points in the book, I make use of thought experiments that have this rough form. The one that I put a lot of emphasis on is a thought experiment involving factory farming, where you have the choice of reincarnation as the bad cases of industrialised pig farming and industrialised chicken farming — you could come back as a factory farmed pig or chicken — or not come back at all, not have a reincarnation event at all. And I would rather not come back at all than have those lives.

Whereas something that marks a big contrast, for me, between industrialised farming of those kinds and the best kinds of humane farming is I’d quite happily come back as a cow on a humane farm. So those kinds of reincarnation and floating-soul-gets-anchored-somewhere thought experiments are ones that I can’t push away when they’re inconvenient, because I make use of them.

OK, so would I, as a floating soul, come back as a random…? Well, a random wild mammal or a person around now? I think I would choose to be a person around now. And I’m not sure to what extent that reflects just a familiarity and an affection for the human mode of life, and to what extent it reflects something more than that.

Luisa Rodriguez: Yeah, I agree that element makes it really hard for me to personally feel like I could answer this question in some way that I really actually buy. But the fact that I have that intuition and that it lingers when I really try to picture even idyllic lives in wild nature feels moving to me.

And maybe it gets at another reaction I have: I feel like when I read the chapter and one of your take-home points is like, it’s kind of ungrateful, kind of negates or rejects or takes for granted this evolutionary history that has created all of this rich diversity and led us to become a who we are, that does feel compelling to me. And then I have the thought, but if I were a wild animal, and I could choose to be a human instead, I just think I would.

So then, on principle, we shouldn’t be ungrateful, and so we should kind of keep the balance as it is — but if there are some wild animals who wouldn’t keep the balance as it is, I feel like it’s a bit rich to maintain that balance on this principle.

Peter Godfrey-Smith: I’m just back a week or so ago from a trip to central Australia. I went on just a solitary, brief wildlife trip, and I spent nearly all the time hanging out with some birds, wild budgerigars — the little parrots that are often kept in cages these days. I found a spot where there were thousands of them, and spent almost all the time I had available just hanging out there. That’s how I tend to do wildlife things: I tend to go back to the same places and stay in the same place, and just try to get a sense of the rhythms and the passage of a day for the animals in that place. What it’s like.

They looked to me to be having a fantastic time, I must say. They zoom around. They will not stop yelling at each other. They didn’t seem under much threat from anybody. There were some birds of prey around, a couple of big kites. But the budgerigars did not seem remotely scared of these large birds of prey — just because the budgerigars, I think, are much faster. So they were even hanging out beside the nests of the kites some of the time, and just rocketing around, interacting, yelling at each other all day. And that’s part of wild nature. It’s not just the tough stuff, that’s a real part of it.

Luisa Rodriguez: Yeah. I feel like we do come close to agreeing in lots of areas, and then maybe it is something about the extent to which the suffering weighs on me. And, to be honest, the extent to which I actually haven’t probably had nearly as much experience in wild nature as you have, and probably don’t have a very good visceral sense of what all the positives in nature are like.

But maybe just to wrap up this section: If this were a research field, and we looked really hard at the kinds of lives different species were living, and there were things that were obviously on the bad side and obviously on the good side, what do you, at the end of the day, think would be the best way to respond to that? Let’s say that we actually have practical tools to somehow either address disease or to reduce the populations of the species that seem to more commonly be suffering extremely.

Peter Godfrey-Smith: One way to understand that question is to ask: Is there any circumstance where this research programme could lead to findings to which the right response would be, “Oh my god, wild nature is just 100 times worse than I thought. We just have to do what we can here”? At a certain point in the book, I grapple a bit with that. I thought, if I’m defending rewilding and the prevention of habitat degradation and so on, based on my rough picture of what’s going on, would I do things differently if my picture of what was going on was quite different?

Now, one thing that does have to be brought in here is just the likelihood of our screwing things up by our intervention. So in the text at one point, Lori Gruen is a philosopher who has made this case against McMahan, who’s the guy who thinks we should intervene to reduce predation. And I sort of move past the point, in a way, thinking, “Right, yes. Absolutely true. But I don’t want everything to depend on that relatively practical consideration, because maybe we could be sure.”

But that does press back on us in your scenario here. We’ve got to ask, what chance is there, really? I mean, given the history of… Australia is a good case here, where there have been quite a number of deliberate introductions of animals with what seemed like sensible reasoning behind it, and I think it’s pretty much always been a mistake. It’s just never been good. So the short-sightedness of human action and the difficulty of implementing these things is a big point.

But I think the basic answer to your question is that, yeah, I can imagine a circumstance where what we learn just makes things look so grim, so tough, that it would be a reasonable evaluative choice on the part of humans to say, “Thank you, Darwinian evolution and natural ecologies, for getting us to this point. We are the beneficiaries of that process. But when we look over how it is now, we think it’s actually something that would be better off if it was radically transformed and curtailed.” I don’t think that’s an impossible or crazy or wholly unreasonable conclusion.

Luisa Rodriguez: OK. I really, really enjoyed that. Thanks for being up for doing some back and forth. And it sounds like we both agree that probably learning more about the lives of wild animals for people who worry about this seems like a good thing to do.

Thinking about death [00:32:50]

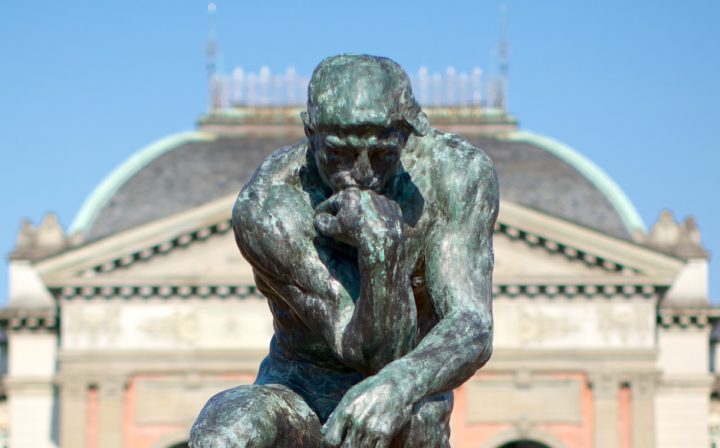

Luisa Rodriguez: The final chapter of your book considers whether death is something we should accept, and I guess that’s desirable. How do you think about death?

Peter Godfrey-Smith: “Desirable” is too strong a word, because that makes it sound like there’s a completely open slate of possibilities here: never dying, dying soon, dying in a long time — what’s the desirable thing?

Something that I want to emphasise in that last chapter is that, although one can think of oneself and one’s fate in a very disembodied way, as a thought experiment, it’s also possible to think about our actual place in the physical world as parts of the endless processes of recycling, as part of animal evolution, as part of ecological change. The way that the molecules in our bodies pass into totally different systems after we’re gone, the way that we came out of materials of very different kinds through these recycling processes, we can think about our place there.

And I like life very much, and have no interest in dying in the near future. But I do look at the whole system, and at the role of bodies like mine, ours, our bodies in the whole system, and I think it’s fine to pass in and out of existence. You know, it makes sense that we will. It’s something that I think is very hard for it not to happen. There’s a passage we might discuss about uploading ourselves as software into the cloud and things like that. I don’t think that’s going to happen; I don’t think that’s feasible.

Once we think of our lives in a kind of grounded way, and also think of ourselves as, in a sense, sort of taking up slots that can be filled by others in the future, other living beings, then the coming into existence and going out of existence seems to me to be… It’s not that I’ll welcome it when the day comes, I don’t think. But looking at the whole. I think it’s fine as a whole, you know? I’m fine with that general picture.

Luisa Rodriguez: Yeah. I think the closest I got to your position was when you brought in Derek Parfit’s view of the self, which I’m going to butcher, but is something like our attachment to ourselves as individuals is probably not actually really reflective of what the self is like. Probably over time we are many different selves as we change. And we have this kind of illusion, if you will, that we are one self over time, but the picture is probably more complicated than that.

If I kind of adopt that perspective, then the boundary between my self continuing and another self living does feel more like one that I can accept and embrace — because the boundaries are just softened between me and other beings, and I feel more excited about other lives and not just about my own.

Peter Godfrey-Smith: That’s my understanding of Parfit’s picture, so that’s not at all butchered. And yeah, I have some of the same thing. Now, Parfit’s making the point in a way that starts from a negative argument, which is that there’s less of a self there than you think; there’s less of a kind of enduring whole core to yourself than you realise — and once you move away from a kind of excessive reification of a continuing self, you’ll see that concern for other beings is not so different from concern for the future version of you, for example.

Luisa Rodriguez: Right.

Peter Godfrey-Smith: And I basically agree with that.

Luisa Rodriguez: Yeah, I think I did too.

Peter Godfrey-Smith: But I want to add the idea that it’s not just a negative point. You can make a positive case based on the way in which the materials that make us up have been recycled and run through these processes that unify life as a sort of historical object on Earth. It’s possible to see a more positive kinship as well as the kind of fragmenting move that Parfit wanted to make.

Luisa Rodriguez: Yeah, I actually find that compelling. I feel a little bit more accepting of death when I think about it that way.

Uploads of ourselves [00:38:04]

Luisa Rodriguez: One kind of assumption there is that there are finite slots. And I think you grant that, even just going forward — because of changing fertility rates, and population growing slower and maybe even declining at some point — it might not be the case that there are finite slots.

Another way there might not be finite slots that you’ve just mentioned is the potential for uploading our brains and creating digital-mind versions of ourselves. But you’ve just hinted that you don’t believe this is feasible. Why are you doubtful that we could create uploads of ourselves?

Peter Godfrey-Smith: My view on that comes from the general position that I’m developing — slowly, cautiously — on the biology of conscious experience, or the biology of felt experience. This was developed in a bit more detail in the second book, but it has a discussion in Living on Earth as well.

The view that I think is most justified — the view I would at least put money on — is a view in which some of what it takes to be a system with felt experience involves relatively schematic functional properties: the way that a system is organised in relation to sensing and action and memory and the internal processing and so on. And some of those, what are often referred to as “functional properties,” could exist in a variety of different physical realisations, in different hardwares or different physical bases.

But I don’t think that’s the whole story: I think nervous systems are special. I think that the way that nervous systems work, the way that our brains work… There are two kinds of properties that nervous systems have. There’s a collection of point-to-point network interactions — where this cell makes that cell fire, and prevents that cell from firing, the spiking of neurons, and the great point-to-point massive network interactions.

And there’s also other stuff, which for years was somewhat neglected I think in these discussions, but which I think is probably very important. There are more diffuse, large-scale dynamic properties that exist within nervous systems: oscillatory patterns of different speeds, subtle forms of synchronisation that span the whole or much of the brain. And these are the sorts of things picked up in an EEG machine, that kind of large-scale electrical interaction.

And I didn’t come up with this myself. There’s a tradition. Francis Crick thought this, neuroscientists like Wolf Singer, a number of other people have argued that this side of the brain is important to the biology of conscious experience, along with the sort of networky, more computer computational side of the brain: that both sets of properties of nervous systems are important. And in particular, the unity of experience — the way in which brain activity generates a unified point of view on the world — has a dependence upon the oscillatory and other large-scale dynamic patterns that you get in brains.

Now, if you look at computer systems, you can program a computer to have a moderately decent facsimile of the network properties in a brain. But the large-scale dynamic patterns, the oscillatory patterns that span the whole, they’re a totally different matter. I mean, you could write a program that includes a kind of rough simulation, where you’d know what was happening if the physical system in fact had large scale dynamic patterns of the relevant kind, but that’s different from having in a physical system those activities actually going on — present physically, rather than just being represented in a computer program.

I do think there’s a real difference between those generally, and especially in the case of these brain oscillations and the like. You would have to build a computer where the hardware had a brain-like pattern of activities and tendencies. People might one day do that, but it’s not part of what people normally discuss in debates about artificial consciousness, uploading ourselves to the cloud and so on.

People assume that you could take a computer, like the ones you and I are using now, with the same kind of hardware, and if you just got the program right — if it was a big powerful one and you programmed it just right — it could run through not just a representation of what a brain does, but a kind of realisation and another instance or another form of that brain activity.

Now, because I think the biology of consciousness is just not like that — I think that the second set of features of brains really matter — I think that it will be much harder than people normally suppose to build any kind of artificial sentient system that has no living parts. It’s not that I think there’s a kind of absolute barrier from the materials themselves — I don’t know if there is — but I certainly think it would have to be much, much more brain-like. The computer hardware would have to be a lot more brain-like than it is now.

I mean, who knows if we could build large numbers of these, powered with a big solar array, and replicate our minds in them? I think it’s very unlikely, I must say. Now, whether that’s unlikely or not, I don’t think I should be confident about. The thing I am a bit confident about, or fairly confident about, is the idea that there’s lots of what happens in brains that’s probably important to conscious experience, which is just being ignored in discussions of uploading our minds to the cloud and things like that.

Luisa Rodriguez: Yeah, that’s really helpful. I don’t know very much about these large-scale dynamics. Are they a result of neuronal firings, or are they a result of other things going on in the brain?

Peter Godfrey-Smith: This is quite a controversial point, actually. It’s a good question. The sense I have — and I’m continually trying to learn the latest on this — is that most of the activity in those large-scale dynamic patterns is not just a summing together of lots of firing of neurons. Because if it was, then you might say that the network, point-to-point, cell-to-cell things really are all that matters once you’ve really captured those, and the other stuff is just a consequence or a kind of zoomed-out manifestation of that.

And that does not seem to be the case. It seems rather that within the cells that make up our brain, there’s a kind of to and fro of ions across membranes that is below the threshold that is required to actually make the neuron fire, that dramatic spark-like firing. It’s more of a kind of rhythmic, lower-level, sub-threshold electrical oscillation.

And those oscillations affect the firing of neurons, and the firing of neurons affect the oscillations. But there is a kind of duality of processes there, and it’s not just that if you knew which cells were firing when, and you ignored everything else, that you could recapture, in a sense, the large-scale dynamic patterns. There’s more than that.

Luisa Rodriguez: Right. So if you take this kind of, for me, what has been a very intuitive, but I guess would feel like an inadequate thought experiment of replacing each neuron in the human brain, one by one, with an artificial silicon-based one, it sounds like you would guess that doing that, even if you got that to work, it wouldn’t make the entire process and physical system of the brain be entirely artificial? There would be other things that remained biological that were playing a crucial role that you hadn’t replaced and replicated yet?

Peter Godfrey-Smith: Well, the way you described it, you made it sound like at the end of this process, the biological parts were gone. So is it that we really replace everything, or is it just we replace some stuff and leave some of the biological material in place?

Luisa Rodriguez: I think I’m curious about if you just replaced neurons with synthetic neurons, do you think there would be a working brain at the end? And if so, would that be because the other biological stuff was still there?

Peter Godfrey-Smith: OK, right. I see. It’s a commitment of my view that if you tried to do that, you would change all sorts of stuff: you can’t really preserve the things that the brain is doing at the start and have them continue once the neurons have been replaced by artificial devices.

I mean, what are the “artificial devices”? When people talk about thought experiments of this kind — which they’ve done, I think, in quite interesting ways for about 40 years now — what they usually imagine is you’re replacing each neuron with a kind of relay object that sums up the inputs coming in and either fires or doesn’t fire, and its firing then contributes to the inputs to various other downstream cells. And it’s just doing that. It’s not doing anything else.

Now, if the things you put into the brain were just doing that, then essentially you would drop all those large-scale dynamic patterns. They just wouldn’t exist anymore. They would be gone. So it would be a different thing physically. It would do different things, because the relationship between the firing of neurons and those slower oscillations does make a difference to how the brain works, so you would change some stuff that would have consequences.

Now, something that people haven’t talked about so much is whether you could put in an artificial object that did really everything that the neuron is doing, where there’s this sort of seepage of ions across the borders, and it has subtle effects on the electrical properties of neighbouring cells and so on. A replacement that captured a lot more of what a neuron did.

And then we reached the point where we got to a few minutes ago, where I said who knows what artificial hardwares might be possible? I don’t think I know nearly enough about these matters to be confident that you could never build something that did that.

Luisa Rodriguez: Just to make sure I understand your position on this: it’s not that you’re confident that it’s impossible to create digital minds in general, or that it’s impossible to eventually come up with some hardware system that does replicate everything relevant to consciousness in a human — but that the current thought experiments where we only replicate some of the basic functions of a neuron are not enough.

Peter Godfrey-Smith: There was a phrase you used — “digital minds” — and I guess I don’t think there will ever be digital minds. I think that’s imagining a system which lacks too much of what brains and nervous systems are like in order for it to have a mind. I don’t know if there might be wholly artificial minds in the future that are made of different stuff than brains are made of, but that have the important duality of properties that you see in nervous systems, and thereby achieve a kind of sentience. I think it’s further away than people often suppose, but I would not want to say it could never happen.

The thing I want to press on in a kind of critical way is the habits that people have of thinking… People think, “I know what neurons and nervous systems do. It’s like a telephone exchange: you’ve got this thing that makes that thing go, and it’s like a big network, and that’s all there is to it.” They think that, and then they think, “Well, a computer is a place where I can have that kind of thing going on, replicated to a high degree of fidelity. So I know that an ordinary computer has what it takes as hardware to be sentient, basically, to be conscious if I put the right program in there — because the program would just have to create a version of those networked, point-to-point interactions.”

That claim I do want to push back against. I don’t think we have any reason to believe that. And I think that artificial sentience is just going to be a harder and further-in-the-future thing than we have supposed. And as I say at one point in this book, Living on Earth, I’m not sure whether that’s a bad thing. If there turns out to be a kind of barrier between the I side of AI — the intelligent side of AI — and the kind of conscious, sentient, feeling side of artificial minds, if there’s a barrier there, that might not be a bad thing.

One reason for that is if we start building lots of sentient systems that have this different kind of hardware, and they’re under our control, we made them — I don’t know how likely it is that their experiences are going to be positive, at least in the early stages. It’s going to be a sort of a klutzy, messed-up version of artificial sentience that we’re working with. And if I’m a disembodied spirit of the kind that you were talking about earlier, I don’t want to come down to Earth and live as an early effort in the human attempt to make artificial sentient systems.

Luisa Rodriguez: Man, there’s a lot there, but I think that’s a good place to leave that topic for now.

Culture and how minds make things happen [00:54:05]

Luisa Rodriguez: Another part of your book explores why humans became technologically advanced, but no other species has. Lots of people might kind of intuitively think that it’s our intelligence, but you think there’s more to it than that. Can you talk through why you think that, or what you think the other elements are?

Peter Godfrey-Smith: Sure. I do think there’s more to it. And the more is pretty well summed up with one word, which is “culture” — the idea that humans are a cultural species. Now, when I say culture, I mean that in a broad sense: the sense that’s often now used in fields like anthropology, where culture is not Beethoven — although we get to Beethoven eventually.

Culture is the tendency or the practice in human communities of picking up behaviours and ideas and skills by watching others: by imitating, by learning and teaching, by seeing what seems to work, by becoming immersed in a community in which behaviours of certain kinds are treated as normal for that community. And each new individual member of the community picks up behaviours in this way.

If we look at other large-brained and intelligent animals, some of them are kind of well set up for culture, such that you could see them going down that road if circumstances changed a little — for example, if we got out of the way and they had more room — and others are really not well set up.

And it was thinking about a particular contrast that helped me a lot in this area. Octopuses are here (as so often) the great contrast case, the great informative weirdos in this area. Octopuses have very large brains, very complex behaviour, and they’re fairly smart — but they are not at all cultural, it seems, and they’re not poised to pick up that way of living either. Partly because of their short lives, but the more important fact is what kind of relationships you have between young and old in octopuses.

If you’re an octopus, you’re born, you become a larva drifting in the sea. You never hang out with your mother, let alone your father; you just make your own way, and never have any opportunity to pick up skills that the older generation might have picked up in its life. It’s all from scratch if you’re an octopus: what you have to go on is what your genes have given you and what your own individual experience gives you. That means that they are a sort of far-from-cultural species.

Now, in some earlier discussions in this area, people used to think that culture really is a human thing, and no other animal has more than the faintest glimmer of it. That’s pretty clearly not true. There’s elements of cultural learning and the cultural acquisition of behaviours in quite a lot of primates, in dolphins, in birds, in various other animals. In the book, I talk about some examples which really have this kind of liminal, just-a-hint character — in the case of birds — and that’s what I think of as the key.

Here I follow, to a large extent, Joe Henrich, who’s a Harvard anthropologist. He wrote a book some years ago called The Secret of Our Success, which is about how that secret is culture: picking up ideas and practices culturally. I think he makes a strong case, and other people have made a strong case along similar lines.

There’s more we might talk about here, but that’s idea number one.

Luisa Rodriguez: To make sure I’m understanding the case: individuals can be very intelligent, and can learn things to make their lives easier or to make them more successful — but the benefit of culture is you pass down lessons across generations, so individuals don’t have to learn everything from scratch. You can accumulate knowledge, ideas, skills, different forms of tool use at some point — and that is enormously more valuable than even just an individual who’s hyper, hyper intelligent?

Peter Godfrey-Smith: That’s right. The way that Henrich describes it, is at a certain point in our history, “humans crossed the Rubicon.” The metaphor here is referring back to Julius Caesar’s crossing a river and marching on to Rome. Having crossed that river, there was no point in turning back. It was a kind of irreversible step.

And that idea of an irreversible step is what Henrich has in mind: the idea that after a human community has developed enough of these skills and enough knowledge about its local environment and how to live, that if an individual was born into that physical environment and had to get by, there’s just no way, in their own lifetime, they could learn quickly enough and effectively enough to become as skilled at living there as people within the culture. There’s just no way.

Henrich also emphasises, rightly, not so much a contrast between the locals and a kind of lone individual starting from scratch — but a contrast between the locals and Europeans making their way into lands occupied by Indigenous peoples. In places like Australia, especially: well-equipped and smart people, lots of support, all sorts of technology that you might think would be just what they need, and they fail miserably. They die unless they’re helped by the local Indigenous population, which they often were. They turn back, leaving a trail of bodies behind.

There’s just no way to be a capable human in lots of the environments in which we live unless you have cultural knowledge, unless you’ve been brought up in a way that makes it clear to you what you can eat, what you can’t eat, how you should respond to the seasons, how you should do all sorts of things.

So the idea is that just being very smart — as we’ve seen in actual human history — doesn’t get you very far. What’s important is being part of a community that has accumulated knowledge of the relevant kind.

Challenges for water-based animals [01:01:37]

Luisa Rodriguez: Right. And thinking about dolphins, whales, octopuses: some of the factors that seem limiting that you’ve already touched on are, in the case of octopuses, lifespan and something like socialness. What’s going on for whales and dolphins, who do have long lifespans and arguably very social lives?

Peter Godfrey-Smith: Very social and very intelligent and long lifespans. I think, roughly speaking, there’s three very interesting contrasts we can draw between ourselves and other animals in this kind of discussion. The octopus one, where you have a mostly asocial, very much not primed for culture kind of animal. And then you have the case of animals like dolphins and whales. In this case, I think part of the story of why they don’t live like us, why they didn’t go down the kind of road that we did, involves the kind of bodies that they have.

Here I’ll draw a little bit on some ideas from the second book in the trilogy, Metazoa. If you look at the evolution of bodies and behaviour going way, way back — hundreds of millions of years back — there’s a trio of animal groups or collections of species, a trio in which you have what a guy called Michael Trestman christened “complex active bodies”: bodies where you can move a lot, you can manipulate, you can target your behaviours on other things; you have good senses, including image-forming eyes that can present objects in space and so on.

The three groups of animals that have some species with complex active bodies are our group, the vertebrates: you know, mammals and birds; arthropods, the group that includes insects; and that weird renegade group of mollusks: the octopuses and to some extent the cuttlefish. So you’ve got three kinds of animals with complex active bodies, all of which had pretty much that kind of body for quite a few hundreds of millions of years.

But suppose we list three features that involve further refinements within that idea. One is the capacity for manipulation: being able to sort of fiddle with things, and transform raw materials into new objects. Manipulation is number one.

The second one is a kind of behavioural open-endedness: being able to do things that are relevantly different than what’s been done by other members of your species, being able to act in genuinely novel ways. That’s number two.

And the third one is having a centralised control system: having a nervous system that is quite centralised and can then become the basis for a certain kind of intelligence when that brain, that central nervous system, becomes big.

So we’ve got those three properties. Now, if you look in the sea at various kinds of animals, you see lots of animals that have two out of the three, but not three out of the three. For example, octopuses are great at manipulation, and they’re very behaviorally open-ended. They can do new things, but they don’t have a centralised control system.

Fish have a centralised nervous system, but there’s not much that they can do; there’s not much scope for manipulation with the fish body. There’s some. I mean, the jaw was a great invention for fish, and I’ve occasionally heard the fish’s jaw described as a kind of a Swiss army knife on your face. But it’s not really very accurate, because there’s not that much you can do with it. So open-endedness of manipulation is not really a factor there either.

Then you’ve got arthropods: animals like crustaceans — crabs and lobsters and things like that — and they really can manipulate all sorts of things; they’re continually evolving appendages for doing weird, manipulative stuff. But they’re not very open-ended animals. It’s hard for an arthropod, given the machinery it has, to behave in genuinely novel ways, even if it wanted to. That’s a feature of the kind of specialised hard parts that their appendages are.

And I mean, if you’re going to talk about Swiss army knives, an arthropod’s whole body is like a Swiss army knife. And in two senses: a Swiss army knife can be used to do all sorts of stuff, but only the stuff that’s sort of pre-programmed or pre-specified. All the parts have a specific purpose.

OK, so in the sea, you have various animals with some combination of one or two of these features, but no one has all three. It’s on land, with the evolution of land vertebrates — especially after the Triassic, and especially in the case of mammals and birds — that you have all three together.

You have a centralised system, because we inherited our neural design from fish. You have lots of scope for manipulation, because you’ve got appendages of really an ideal kind for that. But those appendages are a bit more like octopus arms than arthropod appendages, because they’re more able to do genuinely new stuff; they’re not as circumscribed by their special purposes.

Now, dolphins are stuck with kind of a fish body, basically: manipulation, transformation of materials, there’s only so much of that you can do, and not very much, if you’re a dolphin. So I think that’s an important thing that distinguishes us from them. Unlike the octopuses, they’re very social and they can learn by imitation. They have a sort of cultural style to them, but there’s only so much they can physically do in action. Octopuses can do tonnes of stuff with all those arms, but culture is miles away from what they can manage.

Luisa Rodriguez: Right. Yeah, I was really struck when reading your book by the role of just the physics of water influencing which species go in this direction. Obviously, octopuses are an exception. But one of your descriptions was like, it’s hard to hammer in water. There are lots of types of motions that are much more difficult. Plus, my understanding is that motion is much more passive, because of currents in water that you don’t get on land.

And because of those reasons, you get the kinds of bodies that most water-based animals have. That really helped me understand why it isn’t dolphins. Am I reasonably reflecting your argument there?

Peter Godfrey-Smith: Yes. The idea is that there are some kinds of actions that come very readily in water and others that are difficult and become easy on land, and there are other actions that go the other way. And as a consequence of this, I think there’s a kind of natural transition.

The importance of sea-to-land transitions in animal life [01:10:09]

Peter Godfrey-Smith: Perhaps we could spend a bit of time on this, because I’m currently working on a pair of talks which I’ll be giving at conferences of various kinds that are going to touch on the question of extraterrestrial intelligence and how animal intelligence might evolve on other planets. And one of the things I want to emphasise in my attempt to make a contribution to this discussion is the importance of sea-to-land transitions in animal life.

The idea is it’s very natural for animals to start in the sea. On Earth that’s how it happened: all animal life was confined to the sea for its early stages, all through the Cambrian and the first part of the next period, the Ordovician, for example. And in the sea, some stuff is easy.

You mentioned the passivity of motion in the sea: it’s fair to say you have the option of a kind of passive motion in the sea. You don’t have to. You could swim very actively, but you don’t have to. You can just drift with the currents. Food will come to you if you put yourself in the right location. You can suspension feed or filter feed. You don’t have to put in the tremendous effort and skill that’s involved in moving around on land.

So motion comes easily in the sea. And you don’t have to worry about drying out, which is a huge problem on land. Ultraviolet radiation is a big problem on land. There are lots of things on land that are big challenges.

But if you can make your way onto land — which arthropods were the first animals to do (they’re always the leaders, it seems), and then some other groups did, including vertebrates — then you find there’s a scope for actions of new kinds, especially in the area of transformation: engineering, working with raw materials, making the environment different than how it was before.

So I think that if we’re asking about not just what patterns are there, how we should think about our own earthly transition from simpler to more complex behaviour, but also asking about how things might go elsewhere on other planets, then a sea-to-land transition is a kind of natural thing to expect.

And that’ll have further consequences. For example, it’ll mean that the kinds of bodies that we find on land are built out of designs that had to make sense initially in the sea. There’s a book from some years ago by a biologist, Neil Shubin, called Your Inner Fish, and it’s about the way that the fish design is still present in us.

And we can say that will be true I think generally: animals on other planets, even if they’re on land doing technologically capable things, they will probably have an inner fish, or an inner marine ancestor that’s perhaps not a fish, but something like that as well.

Now, once you’re on land, it’s not just the simpler kinds of tool use and engineering in a minimal sense that comes more readily, but real engineering — for example, working with metals, achieving high temperatures with which you can smelt and purify and blend to make alloys. The whole realm of metal-based technology is probably strongly dependent on the circumstances and the resources that are available on land.

So I think when or if we come across some intelligent aliens, there’ll be things we recognise in them that are perhaps unobvious when one thinks about this initially. They’ll be the products of a sea-to-land transition. They’ll have that mark in their bodies in some ways, but in order for them to be technologically capable, they’ll have had to deal with the challenges of land in something like the way that we have.

Luisa Rodriguez: Yeah. I sometimes find it interesting to think about the extent to which things that have happened and things that will happen were very contingent, or whether they were very inevitable. And this feels like it’s pushing on the inevitable — like there really are narrower paths to the kinds of existences humans live than one might think more naively.

Which reminds me of another thing you describe in your book: the Great Oxygenation of the atmosphere. Do you think that’s another example of a thing that might have to happen for life on a planet to even arise and then follow the same kind of route that we’ve followed?

Peter Godfrey-Smith: There’s a famous book from decades ago by Stephen Jay Gould called Wonderful Life, where he emphasises at great length and skilfully the idea of the profound contingency in evolutionary processes. He thinks that if we ran the tape back and then played it forward again with circumstances a little different, there’s no reason to expect that we’d wind up in a similar place to how we actually are now.

Gould’s book was very influential, and when I read it, I thought back then that, yeah, this is the sort of natural thing to expect. There’s probably a kind of error that’s easy to make where we think that things are set in a particular channel and would wind up in a similar place if the tape was replayed.

And a consequence of working on especially this book, the third book, Living on Earth, has been that I guess I’m much less of a contingency person in some respects now than I was before. When Gould’s book came out, one of the biologists that he discussed in the book, Simon Conway Morris, pushed back on these claims about contingency. And I haven’t actually read Morris’s well-known book about this, but I’m probably a bit more on his side.

But let’s talk about some stages. When Gould made that case about contingency, he was starting the story around the time of the Cambrian — so 540 or so million years ago — and saying that if you ran things forward, you’d expect things to be very different.

And for various reasons, I find myself saying, well, maybe not so different. You should expect animals that have relevant similarities to what we find here, you should expect a sea-to-land transition with a similar role, and so on.

But if we go back much further — to the Great Oxygenation that you mentioned a moment ago — things look different. And this also was a very thought-provoking area for me when I began to learn a little bit about those events. The picture you get from people who work on the evolution and the role of oxygenic photosynthesis — the invention of the kind of photosynthesis that releases oxygen gas as a byproduct, and thereby makes animal life possible — the picture you get from those people is one where… And I’m thinking especially here of Andrew Knoll, who’s another Harvard guy who works on early life: he says it was very hard to invent oxygenic photosynthesis.

There’s other kinds of photosynthesis. There’s other ways of using light and various raw materials to build living material without releasing oxygen gas. The special kind, the oxygen-producing kind, was hard to evolve. It involved bringing together two different machines, essentially, that were themselves machineries of photosynthesis in their own right, and you put the two together and you get a combination. It was hard to evolve. It involved bringing the two machines together.

Once you do manage it, if you manage it, then you can use water as the supply of electrons in the photosynthesis process. So water is an input, and oxygen gas is one of the outputs. Now, once you’re using water as a kind of raw material here, its effects are just enormous — both ecologically, and we could talk about that, but one of the big effects that’s not so much an effect on the Earth, but just an effect on living systems, is: on a planet where there’s oxygenic photosynthesis, you can have much, much more life than you could without it.

Without this kind of photosynthesis, you might have lots of planets with a little bit of life kind of hiding in some weird crevices, making use of difficult sources of raw materials — and consequently not going very far, not evolving much complexity, not taking over the whole planet. What happened as a consequence of the oxygen-producing photosynthesis was not just the production of the oxygen, but the fact that water is being used as a raw material. So you get heaps of life, lots of life. And because there’s lots of life, there’s more evolution, there’s more novelty, there’s more new kinds of things being produced.

So when I read people like Andrew Knoll, they make it sound like there’s a profound contingency in whether or not you get oxygen-producing photosynthesis, or something similar enough to it, something that enables life to become a kind of major player. That’s really contingent. You could have heaps of planets with a little bit of life, but they never get this, so they never really go anywhere. You never get animals, for example.

Once you get oxygenic photosynthesis, and lots and lots of life, lots of evolution, lots of new things, then maybe the story gets a little bit less contingent from there.

Luisa Rodriguez: That’s fascinating.

Peter Godfrey-Smith: I’ll just briefly mention a note of dissent on that last point. So after I just about finished the book, I was discussing these ideas with a biologist who’s an insect guy, Andrew Barron, who’s one of my favourite people to discuss evolutionary topics with.

And I ran through these ideas and he said, no, that this is a kind of chauvinism; this is being oxygenist. This is a kind of narrow-mindedness, thinking that the only way a planet could acquire lots and lots of life is through a particular chemical pathway. Whereas I read the discussions by people like Andrew Knoll and thought this seems quite convincing to me, that it probably is a deeply contingent stage, whether you get oxygen-producing photosynthesis or not. Andrew Barron just said there’s no reason to believe that; there’s probably tonnes of different ways of doing it.

So I want to just register that as dissent. My book probably reflects more the former Andrew’s picture of the profound importance of oxygenic photosynthesis. But there’s also the second Andrew.

Luisa Rodriguez: Does the second Andrew have hypotheses for other ecological foundations that could also work, or is he just like, oxygen is just one thing, and it’s hard to imagine it’s the only thing?

Peter Godfrey-Smith: Yeah, it was more the latter. It was more the idea that our imaginations are unlikely to be able to encompass what’s really possible here. Nature is more inventive than we give it credit for being.

Luisa Rodriguez: Yeah, I do feel sympathies in both directions. OK, we should leave that there, and I actually think we’ve used all the time we have. Thank you so much. My guest today has been Peter Godfrey-Smith. It’s been a real pleasure.

Peter Godfrey-Smith: Thank you. I’ve enjoyed the discussion. Thanks for having me on.

Luisa’s outro [01:23:43]

Luisa Rodriguez: This was a relatively short episode, and we covered a lot of ground across a range of topics.

If you want to learn more about wild animal welfare, I recommend listening to episode #56: Animals in the wild often suffer a great deal. We ask Persis Eskander what — if anything — should we do about that.

If you want to learn more about digital minds, you might enjoy episodes #173: Jeff Sebo on digital minds, and how to avoid sleepwalking into a major moral catastrophe and #146: Robert Long on why large language models like GPT (probably) aren’t conscious.

All right, The 80,000 Hours Podcast is produced by Keiran Harris.

Content editing by me, Katy Moore, and Keiran Harris.

Audio engineering by Ben Cordell, Milo McGuire, Simon Monsour, and Dominic Armstrong.

Full transcripts and an extensive collection of links to learn more are available on our site, and put together as always by Katy Moore.

Thanks for joining, talk to you again soon.