Extreme power concentration

Introduction

Power is already concentrated today: over 800 million people live on less than $3 a day, the three richest men in the world are worth around $1 trillion, and almost six billion people live in countries without free and fair elections.

This is a problem in its own right. There is still substantial distribution of power though: global income inequality is falling, over two billion people live in electoral democracies, no country earns more than a quarter of GDP, and no company earns as much as 1%.1

But in the future, advanced AI could enable much more extreme power concentration than we’ve seen so far.

Many believe that within the next decade the leading AI projects will be able to run millions of superintelligent AI systems thinking many times faster than humans. These systems could displace human workers, leading to much less economic and political power for the vast majority of people; and unless we take action to prevent it, they may end up being controlled by a tiny number of people, with no effective oversight. Once these systems are deployed across the economy, government, and the military, whatever goals they’re built to have will become the primary force shaping the future. If those goals are chosen by the few, then a small number of people could end up with the power to make all of the important decisions about the future.2

Summary

We think this is among the most pressing problems in the world, despite high uncertainty around the scope of the issue and potential solutions.

Our overall view

Recommended - highest priority

We think this is among the most pressing problems in the world.

Scale

The scale of the problem seems potentially very large:

- Some of the mechanisms driving the risk of AI-enabled power concentration seem decently likely (like AI replacing human workers, and positive feedback loops in AI development giving some actors a big capabilities lead).3

- Our top rated problem is power-seeking AI takeover. Some of the same dynamics that could allow misaligned AI systems to seize power could also allow humans controlling AI systems to do so.4

- AI-enabled power concentration would mean the political disempowerment of almost all humans. For the vast majority of people, this would mean having no meaningful say in decisions that shape their lives and futures. Without checks and balances, those in power could make extremely harmful choices — history shows us that unchecked power can lead to tyranny and atrocities.

- What’s even more concerning is that AI-enabled power concentration would likely be self-reinforcing: those in power will probably seek to entrench themselves further and could use their AI advantage to secure their regime, so any harms could be very longlasting.

Neglectedness

Lots of people are working on power concentration generally, in governments, the legal system, academia, and civil society. But very few are focused on the risk of AI-enabled power concentration driven by AI specifically. We’re aware of a few dozen people at a handful of organisations who are working on reducing this risk, and even fewer who work on this full time.

Solvability

Preventing AI-enabled power concentration is so neglected that it’s hard to tell yet how tractable it is. We don’t know yet what works, because so few people have tried anything.

However, there are several reasons to be optimistic here:

- It’s in almost everyone’s interests to prevent AI-enabled power concentration — including the interests of most powerful people today, who might otherwise lose out to their rivals.

- Even though thinking on this problem is at quite an early stage, there are already some concrete interventions that seem promising. For example, technical mitigations which prevent people training AI to advance their own interests, like alignment audits and internal infosecurity, seem quite tractable.

On the other hand:

- The structural forces pushing towards power concentration — AI replacing human workers, and feedback loops leading to large capabilities gaps — might be very strong and difficult to change.

- Even though it’s in most people’s interests to prevent AI-enabled power concentration, their ability to understand what’s happening and act in their own interests might be eroded, if AI progress is very fast, competitive dynamics degrade the epistemic environment, or power-seeking individuals take adversarial actions to deliberately obfuscate what’s happening. Power-seeking people in positions of authority might also be able to simply remove mitigations that others have put in place to limit power concentration, when those mitigations become inconvenient.

Bottom line: it’s not clear how easy it is to solve the problem of AI-enabled power concentration — but it’s not clearly impossible to solve, there are already some tractable things to do, and it’s an important and neglected enough problem that much more effort seems warranted. In fact, our current view is that it’s among the most pressing issues in the world.

Because it’s so early days, and because badly executed plans here could backfire, we think that at the moment most people should be bearing the risk in mind rather than working on it directly, but if you are well placed to work on this problem, it’s pretty likely to be your best option.

Profile depth

Exploratory

This is one of many profiles we've written to help people find the most pressing problems they can solve with their careers. Learn more about how we compare different problems and see how this problem compares to the others we've considered so far.

Table of Contents

- 1 Why might AI-enabled power concentration be a pressing problem?

- 1.1 An AI-enabled power concentration scenario

- 1.2 Automation could concentrate the power to get stuff done

- 1.3 This could lead to unprecedented concentration of political power

- 1.4 AI-enabled power concentration could cause enormous and lasting harm

- 1.5 There are ways to reduce this risk, but very few are working on them

- 2 What are the top arguments against working on this problem?

- 2.1 AI-enabled power concentration could reduce other risks from AI

- 2.2 The future might still be all right, even if there’s AI-enabled power concentration

- 2.3 Efforts to reduce AI-enabled power concentration could backfire

- 2.4 Power might remain distributed by default

- 2.5 It might be too hard to stop AI-enabled power concentration

- 3 What can you do to help?

- 4 Learn more

Why might AI-enabled power concentration be a pressing problem?

The main reasons we think AI-enabled power concentration is an especially pressing problem are:

- Historically unprecedented levels of automation could concentrate the power to get stuff done, by reducing the value of human labour, empowering small groups with big AI workforces, and potentially giving one AI developer a huge capabilities advantage (if automating AI development leads to runaway AI progress).

- This could lead to unprecedented concentration of political power. A small number of people could use a huge AI workforce to seize power over existing institutions, or render them obsolete by amassing enormous wealth.

- AI-enabled power concentration could cause enormous and lasting harm, by disempowering most people politically, and enabling large-scale abuses of power.

- There are ways to reduce this risk, but very few are working on them.

In this section we’ll go through each of these points in turn, but first we’ll give an illustrative scenario where power becomes extremely concentrated because of advanced AI. The scenario is very stylised and there are loads of other ways things could go, but it gives a more concrete sense of the kind of thing we’re worried about.

An AI-enabled power concentration scenario

Note that this scenario, and the companies and institutions in it, are made up. We’re trying to illustrate a hypothetical, and don’t have particular real-world actors in mind.

In 2029, a US AI company called Apex AI achieves a critical breakthrough: their AI can now conduct AI research as well as human scientists can. This leads to an intelligence explosion, where AI improving AI improving AI leads to very rapid capability gains. But their competitors — including in China — are close on their heels, and begin their own intelligence explosions within months. Fearing that China will soon be in a position to leverage its industrial base to overtake the US, the US government creates Project Fortress — consolidating all US AI development under a classified Oversight Council of government officials and lab executives. Apex leverages their early lead to secure three of nine board seats and provides the council’s core infrastructure: security systems, data analytics, and AI advisors.

By 2032, AI companies generate the majority of federal tax revenue as AI systems automate traditional jobs. Unemployment rises. The Oversight Council now directs hundreds of millions of AI workers, controls most of the tax base, and makes the most important decisions about military AI procurement, infrastructure investment, and income redistribution. Only those with direct connections to the council or major AI companies have access to the most advanced AI tools, while most citizens interact with limited consumer versions. When the president proposes blocking Apex’s merger with Paradox AI (which would create a combined entity controlling 60% of compute used to train and run US AI systems), council-generated economic models warn of China overtaking and economic collapse if the move is carried out. The proposal dies quietly. The council’s AI systems — all running on Apex architecture — are subtly furthering Apex’s interests, but the technical traces are too subtle for less advanced models to detect. Besides, most people are bought into beating China, and when they ask their personal AI advisors (usually less advanced versions of either Paradox or Apex models) about the merger, they argue persuasively that it serves the national interest.

By 2035, the US economy has tripled while other nations have stagnated. Project Fortress’ decisions now shape global markets — which technologies get developed, which resources get allocated, which countries receive AI assistance. Apex and Paradox executives gradually cement their influence: their AI systems draft most proposals, their models evaluate the options, their security protocols determine what information reaches other council members. With all major information channels — from AI advisors to news analysis to government briefings — filtered through systems they control, it becomes nearly impossible for anyone to get an unbiased picture of the concentration of power taking place. Everything people read on social media or hear on the news seems to support the idea that there is nothing much to worry about.

The executives are powerful enough to unilaterally seize control of the council and dictate terms to other nations, but they don’t need to. Through thousands of subtle nudges — a risk assessment here, a strategic recommendation there — their AI systems ensure every major decision aligns with their vision for humanity’s future.

Automation could concentrate the power to get stuff done

We’ve always used technology to automate bits of human labour: water-powered mills replaced hand milling, the printing press replaced scribes, and the spinning jenny replaced hand spinning. This automation has had impacts on the distribution of power, some of them significant — the printing press helped shift power from the church towards city merchants; and factory machines shifted power from landowners to capitalists and towards industrialising countries.

The thing that’s different with AI is that it has the potential to automate many kinds of human labour at once. Top AI researchers think that there’s a 50% chance that AI can automate all human tasks by 2047 — though many people think this could happen much sooner (several AI company CEOs expect AGI in the next few years) or much later (the same survey of top AI researchers gave a 50% chance of AI automating all human occupations by 2116). Even if full human automation takes a long time or never happens, it’s clear that AI could automate a large fraction of human labour — and given how fast capabilities are currently progressing, this might start happening soon.5

This could have big implications for how power is distributed:

- By default, less money will go to workers, and more money will go to the owners of capital. Automation could reduce the value of people’s labour, in extreme scenarios causing wages to collapse to very low levels indefinitely. 6 This would increase how much of the pie goes to capital compared to labour, and those with capital could become even more disproportionately powerful than they are now.

- Small groups will be able to do more. Right now, large undertakings require big human workforces. At its peak, the Manhattan project employed 130,000 people. It takes 1.5 million people just to run Amazon. As AI becomes more capable, it’ll become possible to get big stuff done without large human teams — and the attendant need to convince them what you’re doing is good or at least OK — by using AI workforces instead.

- This would already empower small groups to do more. But the effect will be even stronger because using AI to get stuff done won’t empower everyone equally: it’ll especially empower those with access to the best AI systems. Companies already deploy some models without releasing them to the public, and if capabilities get more dangerous or the market becomes less competitive, access to the very best capabilities could become very limited indeed.

- Runaway progress from automated AI development could give one developer a big capabilities advantage. The first project to automate AI R&D might trigger an intelligence explosion, where AI systems improving AI systems which improve AI systems leads to a positive feedback loop, meaning their AI capabilities can rapidly pull ahead of everyone else’s. Competitors might follow on with intelligence explosions of their own, but if they are far enough behind the leader to begin with or the leader’s initial boost in capabilities is sufficiently huge, one company might be able to entrench a lasting advantage.

If these dynamics are strong enough, we could end up with most of the power to earn money and get stuff done in the hands of the few organisations (either AI companies7 or governments8) which have access to the best AI systems — and hence to huge amounts of intelligent labour which they can use for any means.

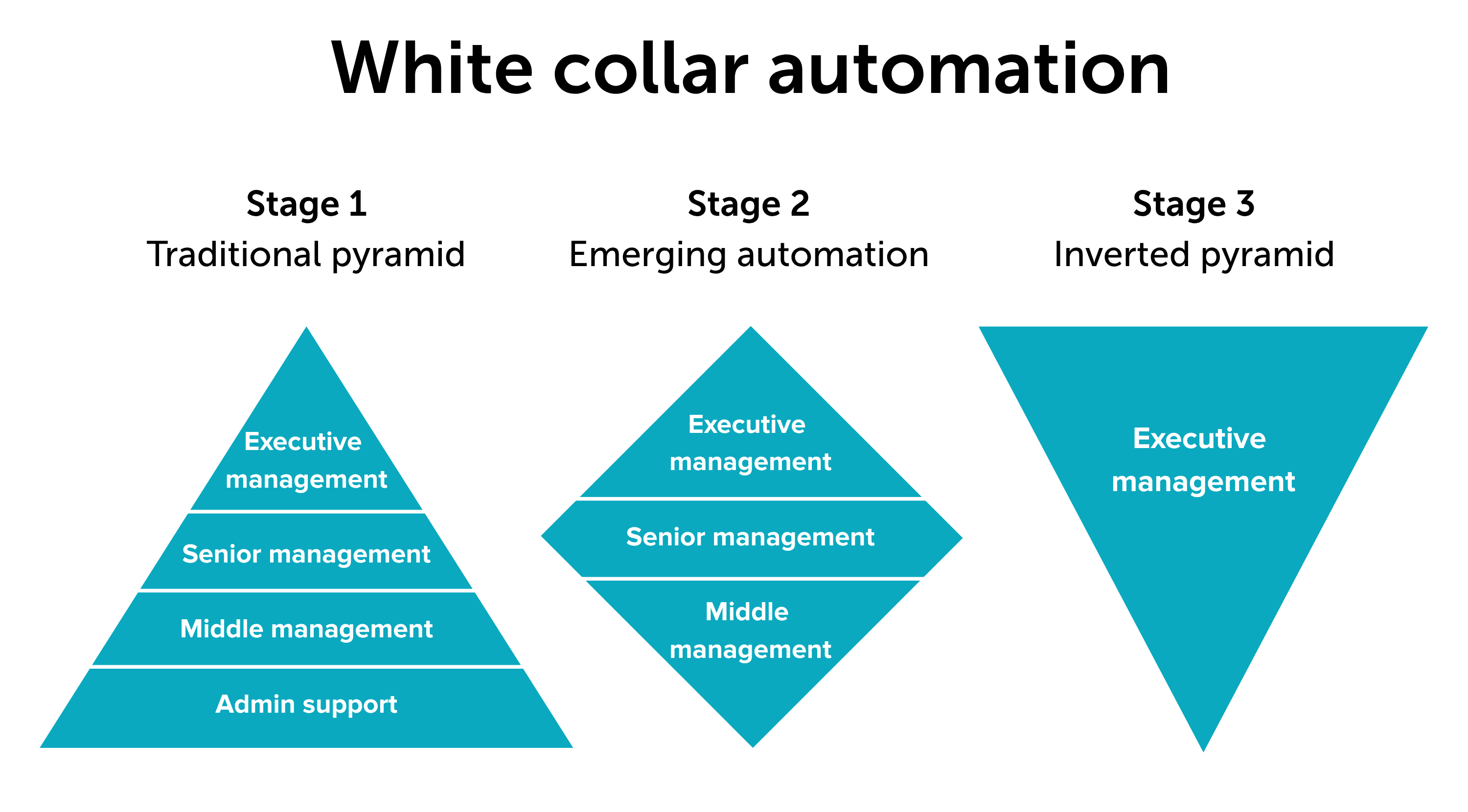

Furthermore, within these organisations, more and more employees may get replaced by AI systems, such that a very small number of people wield huge amounts of power.9

It’s plausible that entry-level white collar jobs will be automated first. Organisations could become more top-heavy, with an expanded class of managers overseeing many AI agents.

There are many other ways this could go, and it’s not a foregone conclusion that AI will lead to this kind of power concentration. Perhaps we’ll see a stronger shift from expensive pre-training to more accessible inference scaling, and there will be a boom in the number of frontier companies, putting equally-powerful AI in more hands. There might be no intelligence explosion, or it might fizzle quickly, allowing laggards to catch up. If commercial competition remains high, consumers will have access to smarter and smarter models, which could even out differences in capabilities between humans and push towards greater egalitarianism. AI might allow for much more direct democracy by making it easier to aggregate preferences, and for greater transparency. And so on (more on this below).

So there are forces pushing against power concentration, as well as forces pushing towards it. It’s certainly possible that society naturally adjusts to these changes and successfully defends against AI-enabled power concentration. But given the speed that AI progress might reach, there’s a real risk that we don’t have enough time to adapt.

This could lead to unprecedented concentration of political power

So we could end up in a situation where most of the power to earn money and get stuff done is in the hands of the few.

This power might be kept appropriately limited by existing institutions and laws, such that influence over important decisions about the future remains distributed. But it’s not hard to imagine that huge capabilities advantages for some actors and the erosion of the value of most human labour could undermine our current checks and balances, which were designed for much more even levels of capabilities in a world which runs on human labour.

But how would this actually happen? People who are powerful today will fight tooth and nail to retain their power, and just having really good AI doesn’t automatically put you in charge of key institutions.

We think that power could become extremely concentrated through some combination of:

- AI-enabled power grabs, where actors use AI to seize control over existing institutions

- Economic forces, which might make some actors so wealthy that they can easily influence or bypass existing institutions

- Epistemic interference, where the ability of most people to understand what’s happening and coordinate in their own interests gets eroded

Experts we’ve talked to disagree about which of these dynamics is most important. While it might be possible for just one of these dynamics to lead all the way to AI-enabled power concentration, we’re especially worried about the dynamics in combination, as they could be mutually reinforcing:

- Power grabs over leading companies or governments would make it easier to amass wealth and control information flows.

- The more that wealth becomes concentrated, the easier it becomes for the richest to gain political influence and set themselves up for a power grab.

- The more people’s ability to understand and coordinate in their own interests is compromised, the easier it becomes for powerful actors to amass wealth and grab power over institutions.

Below, we go into more detail on how each of these factors – power grabs, economic forces, and epistemic interference – could lead to AI-enabled power concentration, where a small number of people make all of the important decisions about the future.

AI-enabled power grabs

There are already contexts today where actors can use money, force, or other advantages to seize control of institutions — as demonstrated by periodic military coups and corporate takeovers worldwide. That said, there are limits to this: democracies sometimes backslide all the way to dictatorship, but it’s rare;10 and there are almost never coups in mature democracies.

Advanced AI could make power grabs possible even over very powerful and democratic institutions, by putting huge AI workforces in the hands of the few. This would fundamentally change the dynamic of power grabs: instead of needing large numbers of people to support and help orchestrate a power grab, it could become possible for a small group to seize power over a government or other powerful institution without any human assistance, using just AI workforces.

What would this actually look like though?

One pathway to an AI-enabled power grab over an entire government is an automated military coup, where an actor uses control over military AI systems to seize power over a country. There are several different ways an actor could end up with control over enough military AI systems to stage a coup:

- Flawed command structure. Military AI systems might be explicitly trained to be loyal to a head of state or government official instead of to the rule of law. If systems were trained in this way, then the official who controlled them could use them however they wanted to, including to stage a coup.11

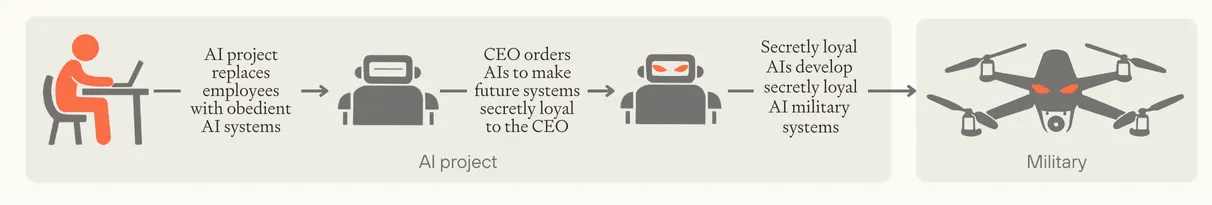

- Secret loyalties. As AI capabilities advance, it may become possible to make AI systems secretly loyal to a person or small group.12 Like human spies, these systems would appear to behave as intended, but secretly further other ends. Especially if one company has much more sophisticated AI than everyone else, and only a few actors have access to it, these secret loyalties might be very hard for external people to detect.13 So subsequent generations of AIs deployed in government and the military might also be secretly loyal, and could be used to stage a coup — either by AI company leaders or foreign adversaries, or by parts of the government or military.

- Hacking. If one company or country has a strong advantage in cyber offense, they could hack into many military AI systems at once, and either disable them or use them to actively stage a coup.

AI systems could propagate secret loyalties forwards into future generations of systems until secretly loyal AI systems are deployed in powerful institutions like the military.

These scenarios may sound far-fetched. Militaries will hopefully be cautious about deploying autonomous military systems, and require appropriate safeguards to prevent these kinds of misuse. But competition or great power conflict might drive rushed deployment,14 and secret loyalties could be hard to detect even with rigorous testing. And it might only take a small force to successfully stage a coup, especially if they have AI to help them (there are several historical examples of a few battalions successfully seizing power even without a technological advantage, by persuading other forces not to intervene).15

Outside military coups, another potential route to an AI-enabled power grab is overwhelming cognitive advantage, where an actor has such a huge advantage in skilled AI labour that it can directly overpower a country or even the rest of the world. With a very large cognitive advantage, it might be possible to seize power by using superhuman strategy and persuasion to convince others to cede power, or by rapidly building up a secret military force. This is even more sci-fi, but some people think it could happen if there’s a big enough intelligence explosion.

An AI-enabled power grab — whether via an automated military coup or via overwhelming cognitive advantage — wouldn’t automatically constitute AI-enabled power concentration as we’ve defined it. There’s no single institution today which makes all of the important decisions — not even the most powerful government in the world. So there might still be a long path between ‘successful power grab over one institution’ and ‘making all of the important decisions about what happens in the future’. But a power grab could be a very important incremental step on the way to a small number of people ending up with the power to make all of the important decisions about the future16 — or if power had already become very concentrated, a power grab could be the final step.

Economic forces

There are several different ways that a small group could become wealthy enough to effectively concentrate power, in extreme cases making existing institutions irrelevant:

- Eroding the incentives for governments to represent their people, by making the electorate economically irrelevant. Of course, the mission of governments in democracies is to represent and serve the interests of their citizens. But currently, governments also have direct economic incentives to do so: happier and healthier people make more productive workers, and pay more taxes (plus they’re less likely to rebel). If this link were broken by automation, and AI companies provided the vast majority of government revenues, governments would no longer have this self-interested reason to promote the interests of their people.

- There might still be elections in democracies, but very fast rates of progress could make election cycles so slow that they don’t have much influence, and misinformation and lobbying could further distort voting. In scenarios like this, there might still be governments, but they’d no longer serve the functions that they currently do, and instead would mostly cater to the interests of huge AI companies.17

- Outgrowing the world, where a country or company becomes much richer than the rest of the world combined. An intelligence explosion of the kind discussed above could grant the leading AI developer a (maybe temporary) monopoly on AI, which could allow them to make trillions of dollars a year,18 and design and build powerful new technologies. Naively, if that actor could maintain its monopoly and grow at a faster rate than the rest of the world for long enough, it would end up with >99% of resources. There are lots of complications here which make outgrowing the world less likely,19 but it still seems possible that an actor could do this with a very concerted and well-coordinated effort if they had privileged access to the most powerful technology in the world. Today’s institutions might continue to exist, but it’s not clear that they would be able to enact important decisions that the company or country didn’t like.

- First mover advantages in outer space, where the leader in AI leverages their advantage to claim control over space resources. If AI enables rapid technological progress, the leader in AI might be the first actor to develop advanced space capabilities. They could potentially claim vast resources beyond Earth — and if space resources turn out to be defensible, they could maintain control indefinitely. It’s not clear that such first mover advantages actually exist,20 but if they do, the first mover in space would be able to make unilateral decisions about humanity’s expansion into the universe — decisions that could matter enormously for our long-term future.

All of these routes are quite speculative, but if we don’t take steps to prevent them, it does seem plausible that economic forces could lead to one country or company having much more political power than everyone else combined. If that actor were very centralised already (like an autocratic government or a company where most employees had been automated), or if there were later a power grab that consolidated power in the hands of a small group, this could lead to all important decisions about the future being made by a handful of individuals.

Epistemic interference

Power grabs and economic forces that undermine existing institutions would be bad for most people, so it would be in their interests to coordinate to stop these dynamics. But the flip side of this is that it’s in the interests of those trying to amass power to interfere with people’s ability to understand what’s happening and coordinate to stop further power concentration.21

This is the least well-studied of the three dynamics we’ve pointed to, but we think it could be very important. Tentatively, here are a few different factors that could erode the epistemic environment, some of which involve deliberate interference and some of which are emergent dynamics which favour the few:

- Lack of transparency. Powerful actors in AI companies and governments will have incentives to obfuscate their activities, particularly if they are seeking power for themselves. It might also prove technically difficult to share information on AI capabilities and how they are being used, without leaking sensitive information. The more AI development is happening in secret, the harder it is for most people to oppose steps that would lead to further power concentration.

- Speed of AI progress. Things might be shifting so quickly that it’s hard for any humans to keep up. This would advantage people who have access to the best AI systems and the largest amounts of compute: they might be the only ones who are able to leverage AI to understand the situation and act to promote their own interests.

- Biased AI advisors. As AI advice improves and the pace of change accelerates, people may become more and more dependent on AI systems for making sense of the world. But these systems might give advice which is subtly biased in favour of the companies that built them — either because they’ve been deliberately trained to, or because no one thought carefully about how the systems’ training environments could skew them in this direction. If AI systems end up favouring company interests, this could systematically bias people’s beliefs and actions towards things which help with further power concentration.

- Persuasion and manipulation campaigns. Those with access to superior AI capabilities and compute could deliberately interfere with other people’s ability to limit their power, by conducting AI-powered lobbying campaigns or manipulating individual decision makers. For example, AI could make unprecedentedly intensive and personalised efforts to influence each individual congressperson to gain their support on some policy issue, including offers of money and superhuman AI assistance for their reelection campaigns. It’s not yet clear how powerful these techniques will be (maybe humans’ epistemic defences are already quite good and AI won’t advance much on what humans can already do), but if we’re unlucky this could severely impair society’s ability to notice and respond to power-seeking.

That list of factors might be missing important things and including things that are not really going to be problems — again, the area is understudied. But we’re including it to give a more concrete sense of how AI might erode (or be used to erode) the epistemic environment, making it harder for people to realise what’s happening and resist further power concentration. Epistemic interference in isolation probably won’t lead to extreme AI-enabled power concentration, but it could be a contributing factor.

AI-enabled power concentration could cause enormous and lasting harm

In a commonsense way, handing the keys of the future to a handful of people seems clearly wrong, and it’s something that most people would be strongly opposed to. We put a fair bit of weight on this intuitive case.

We also put some weight on specific arguments for ways in which AI-enabled power concentration would be extremely harmful, though the reasoning here feels more brittle:

- It could lead to tyranny. Democracy usually stops small groups of extremists from taking the reins of government and using them to commit mass atrocities against their peoples, by requiring that a large chunk of the population supports the general direction of the government. If power became extremely concentrated, a small group could commit atrocities that most people would be appalled by. Many of the worst atrocities in human history were perpetrated by a small number of people who had unchecked power over their people (think of the Khmer Rouge murdering a quarter of all Cambodians between 1975 and 1979). We can think of two main ways that AI-enabled power concentration could lead to tyranny:

- Malevolent — or just extremely selfish — humans could end up in power. Particularly for scenarios where power gets concentrated through AI-enabled power grabs, it seems quite likely that the sorts of humans who are willing to seize power will have other bad traits. They might actively want to cause harm.

- Power corrupts. Even if those in power start out with good intentions, they’d have no incentive to continue to promote the interests of most people if their power were secure. Whenever other people’s interests became inconvenient, there would be a strong temptation to backtrack, and no repercussions to doing so.

- It could lead us to miss out on really good futures. AI-enabled power concentration might not lead to tyranny in the most egregious sense: we might somehow end up with a benevolent dictator or an enlightened caste of powerful actors who keep an eye out for the rest of us. But even in this case, the future might be much less good than it could have been, because there’d be:

- Injustice and disempowerment. AI-enabled power concentration would disempower the vast majority of people politically. From some philosophical perspectives,22 justice and political empowerment are intrinsically valuable, so this would make the future much less good.

- Less diversity of values and ways of life. A narrower set of people in power means a narrower set of values and preferences get represented into the future. Again, from many perspectives this kind of diversity is intrinsically valuable.

- Less moral reflection (maybe). Making good decisions about the future might require thinking deeply about what we value and what we owe to others. If power over the future is distributed, there’s a good chance that at least some people choose to reflect in this way — and there will be more disagreement and experimentation, which could prompt others to reflect too. But if power is extremely concentrated, those in charge might simply impose their current worldview without ever questioning it. This could lead to irreversible mistakes: imagine if the Victorians or the Romans’ moral blindspots had become permanent policy. If those in power happen to care about figuring out what’s right, power concentration could also lead to more moral reflection than would happen in a default world — but it would be limited to a narrow set of experiences and perspectives, and might miss important insights that emerge from broader human dialogue.

Extreme AI-enabled power concentration would also probably be hard to reverse, making any harms very long-lasting. As is already the case, the powerful will try to hold onto their power. But AI could make it possible to do this in an extremely long-lasting way that hasn’t been possible historically:

- Even if most people opposed an AI-powered regime, they might have even less power than historically disenfranchised groups have had to overturn it. If all economic and military activity is automated, humans won’t have valuable labour to withhold or compelling force to exert, so strikes and uprisings won’t have any bite.

- Human dictators die, but a government run by AI systems could potentially preserve the values of a dictator or other human leader permanently into the future.

- If power becomes so concentrated there’s just one global hegemon, then there won’t be any external threats to the regime.23

These harms need to be weighed against the potential benefits from AI-enabled power concentration, like reducing competitive dynamics. We’re not certain how all of this will go down, but both our intuitions and the analysis above suggest that AI-enabled power concentration poses serious risks to human flourishing that we should work to avoid.

There are ways to reduce this risk, but very few are working on them

Many people are working to prevent more moderate forms of power concentration. Considered broadly, a lot of the work that happens in governments, the legal system, and many parts of academia and civil society contributes to this.

But very few are focused on the risk of extreme power concentration driven by AI — even though, if the above arguments are right, this is a very serious risk. We’re aware of a few dozen people at a handful of organisations who are working on reducing this risk, and even fewer who work on this full time. As of September 2025, the only public grantmaking round we know of on AI-enabled power concentration is a $4 million grant programme (though there’s more funding available privately).

This is in spite of the fact that there are concrete things we could do now to reduce the risk. For example, we could:

- Work on technical solutions to prevent people misusing massive AI workforces, like:

- Training AI to follow the law

- Red-teaming model specs (documents that AI systems are trained to follow which specify how they should behave) to make sure AIs are trained not to help with power grabs

- Auditing models to check for secret loyalties

- Increasing lab infosecurity to prevent tampering with the development process and unauthorised access, which would make it harder to insert secret loyalties or misuse AI systems24

- Develop and advocate for policies which distribute power over AI, like:

- Designing the terms of contracts between labs and governments to make sure no one actor has too much influence

- Sharing access to the best AI capabilities widely whenever this is safe, and with multiple trusted actors like congress and auditors when it isn’t, so that no actor has much more powerful capabilities than everyone else

- Building datacentres in non-US democracies, to distribute the power to run AI systems amongst more actors

- Mandating transparency into AI capabilities, how they are being used, model specs, safeguards and risk assessments, so it’s easier to spot concerning behaviour

- Introducing more robust whistleblower protections to make it harder for insiders to conspire or for company executives to suppress the concerns of their workforces

- All of the technical solutions above

- Build and deploy AI tools that improve people’s ability to reason and coordinate, so they can resist epistemic interference

To be clear, thinking about how to prevent AI-enabled power concentration is still at a very early stage. Not everyone currently working on this would support all of the interventions in that list, and it’s not clear how much of the problem would be solved even if we implemented the whole list. It might be that the structural forces pushing towards AI-enabled power concentration are too strong to stop.

But it certainly doesn’t seem inevitable that power will become extremely concentrated:

- It’s in almost everyone’s interests to prevent AI-enabled power concentration — including the interests of most powerful people today, since they have a lot to lose if they get out-competed.

- It’s promising that we can already list some concrete, plausibly achievable interventions even though thinking about how to solve the problem is so early stage.

There’s a lot more work to be done here than there are people doing the work.

What are the top arguments against working on this problem?

We’ve touched on these arguments in other places in this article, but we’ve brought them all together here so it’s easier to see what the weakest points are in the argument for prioritising AI-enabled concentration of power, and to go into a bit more depth.

AI-enabled power concentration could reduce other risks from AI

Some forms of power concentration could reduce various other risks from AI:

- If there were no competition in AI development, the sole AI developer wouldn’t have competitive pressures to skimp on safety, which might reduce the risk of AI takeover. These competitive pressures are a major reason to worry that AI companies will race ahead without taking adequate AI safety precautions.

- The risk of great power war would fall away if power became entirely concentrated in one country.

- The risk of catastrophic misuse of bioweapons and other dangerous technologies would be much lower if only one actor had access to dangerous capabilities. The fact that AI could democratise access to extremely dangerous technology like bioweapons is one of the major reasons for concern about misuse.

That said:

- There are other ways to manage those risks. It’s not the case that either we have a benevolent dictatorship, or we suffer existential catastrophe from other AI risks. Some combination of domestic regulation, international coordination, technical progress on alignment and control, and AI tools for epistemic security could allow us to navigate all of these risks.

- The prospect of AI-enabled power concentration could also exacerbate other risks from AI. It’s one thing to imagine a world where power is already extremely concentrated. But the process of getting to that world might drastically increase the stakes of competition, and make powerful actors more willing to make risky bets and take adversarial actions, to avoid losing out.

- Many interventions to reduce AI-enabled power concentration also help reduce other risks. There isn’t always a trade-off in practice. For example, alignment audits help reduce the risk of both power concentration and AI takeover, by making it harder for both humans and AIs to tamper with AI systems’ objectives. And sharing capabilities more widely could both reduce power differentials and allow society to deploy AI defensively: if we can safeguard AI models sufficiently, this needn’t increase risks from catastrophic misuse.

Weighing up these risks is complicated, and we’re not claiming there aren’t tradeoffs here. We currently think it isn’t clear whether the effects of AI-enabled power concentration net out as helpful or harmful for other AI risks. Given that power concentration is an important and neglected problem in its own right, we think it’s still very worth working on. (But we would encourage people working on AI-enabled concentration of power to keep in mind that their actions might influence these other issues, and try to avoid making them worse.)

The future might still be all right, even if there’s AI-enabled power concentration

For the reasons we went into above, we think extremely concentrated power is likely to be bad. But even if you agree, there are some reasons to think a future with AI-enabled power concentration could still turn out all right on some metrics:

- Material abundance: AI might generate such enormous wealth that most people live in material conditions that are far better than those of the very richest today. In a world with AI-enabled power concentration, people would be politically disempowered, but if the powerful chose to allow it, they could still be materially well-off.

- Reduced incentives for repression and brutality: part of why autocracies repress their peoples is that their leaders are trying to shore up their own power. If power became so concentrated that leaders were guaranteed to remain in power forever, there’d no longer be rational incentives to do things like restrict freedom of speech or torture dissidents (but there’d still be irrational ones like spite or fanatical ideologies.)

- Selection effects: while perhaps not likely, it’s possible that the people who end up in power would genuinely want to improve the world. Maybe getting into such a powerful position selects for people who are unusually competent, and maybe they assumed power reluctantly because people were racing to develop unsafe AI, and power concentration seemed like the lesser of two evils.

Again, we don’t find these arguments particularly compelling, but believe they’re plausible enough to be worth considering and weighing.

Efforts to reduce AI-enabled power concentration could backfire

AI-enabled power concentration is a spicy topic, and efforts to prevent it could easily backfire. The more salient the risk of AI-enabled power concentration is, the more salient it is to power-seeking actors. Working to reduce AI-enabled power concentration could:

- Galvanise opposition to interventions by those who stand to gain from power concentration.

- Directly give power-seeking actors ideas, by generating and publicising information on how small groups could end up with large amounts of power.

- Trigger a scramble for power. If everyone thinks that everyone else is trying to consolidate their power, they might be more likely to try to seize power for themselves to preempt this.

Some interventions might also reduce the probability that one actor ends up with too much power, but by increasing the probability that another actor does. For example, increasing government oversight over AI companies might make company power grabs harder, but simultaneously make it easier for government officials to orchestrate a power grab.

We do think that preventing AI-enabled power concentration is a bit of a minefield, and that’s part of why we think that for now, most people should be bearing the risk in mind rather than working on it directly. But there are ways of making this work less likely to backfire, like:

- Being thoughtful and aware of backfire risks. If you don’t think you have good judgement on this sort of thing (or wouldn’t have anyone with good judgement to give you feedback), it’s probably best to work on something else.

- Using frames and language which are less adversarial. For example, ‘power grabs’ seems spicier than ‘power concentration’ as a framing.

- Focusing on kinds of work that are hard for power-seeking actors to misuse. For example, developing and implementing mitigations like transparency measures or alignment audits is harder for a power-seeking actor to make use of than detailed threat-modelling.

Power might remain distributed by default

Above, we argue that power could become extremely concentrated. But this isn’t inevitable, and the arguments may turn out to be wrong. For example:

- AI capabilities might just not get that powerful. Maybe the ceiling on important capabilities like persuasion or AI R&D is quite low, so the effects of AI are less transformative across the board.

- A particularly important variant of this is that maybe self-reinforcing dynamics from automating AI R&D will be weak, in which case there might be no intelligence explosion or only a small one. This would mean that no single AI developer would be able to get and maintain a big capabilities lead over other developers.

- The default regulatory response (and the institutional setup in places like the US) might be enough to redistribute gains from automation and prevent misuse of big AI workforces. People with power today — which in democracies includes the electorate, civil society, and the media — will try very hard to maintain their own power against newcomers if they are able to tell what’s going on, and most people stand to lose from AI-enabled power concentration.

- If people are worried that AI is misaligned, meaning that it doesn’t reliably pursue the goals that its users or makers want it to, this could both reduce the economic impacts of AI (because there’d be less deployment), and make power-seeking individuals less willing to use AI to attempt power grabs (because the AI might turn on them).

We think that the probability that power becomes extremely concentrated is high enough to be very concerning. But we agree that it’s far from guaranteed.

It might be too hard to stop AI-enabled power concentration

On the flip side, it might turn out that AI-enabled power concentration is not worth working on because it is too difficult to stop:

- The structural forces pushing towards AI-enabled power concentration could be very strong. For example, if there’s an enormous intelligence explosion which grants one AI developer exclusive access to godlike AI capabilities, then what happens next would arguably be at their sole discretion.

- Most actors who could stand to gain from AI-enabled power concentration are already very powerful. They might oppose efforts to mitigate the risk, obfuscate what’s going on, and interfere with other people’s ability to coordinate against power concentration.

That said, we don’t think that we should give up yet:

- We don’t know yet how the structural dynamics will play out. We might be in a world where it is very possible to limit power concentration.

- It’s in almost everyone’s interests to prevent AI-enabled power concentration — including the interests of most powerful people today, since most of them stand to lose out if one small group gains control of most important decisions. It might be possible to coordinate to prevent power concentration and make defecting very costly.

- There are already some interventions to prevent AI-enabled power concentration that look promising (see above). If this area receives more attention, we may well find more.

What can you do to help?

Because so little dedicated work has been done on preventing extreme AI-enabled power concentration to date, there aren’t yet interventions that we feel confident about directing lots of people towards. And there certainly aren’t many jobs working directly on this issue!

For now, our main advice for most people is to:

- Bear the risk of AI-enabled power concentration in mind. We’re more likely to avoid AI-enabled power concentration if reasonable people are aware of this risk and want to prevent it. This is especially relevant if you work at an AI company or in AI governance and safety: policies or new technologies will often have knock-on effects on power concentration, and by being aware of this you might be able to avoid inadvertently increasing the risk.

- Be sensitive to the fact that efforts to reduce this risk could backfire or increase other risks.

There are also some promising early-stage agendas, and we think that some people could start doing good work here already. We’d be really excited to see more people work on:

- Law-following AI. Training AI systems to follow the law and other constraints would make it harder to use AI systems to seize power. Law-Following AI: Designing AI Agents to Obey Human Laws is the main paper on the topic, and includes an agenda with topics for further research.25

- Alignment audits and systems integrity to prevent tampering. This would make it harder for malicious actors to insert secret loyalties or otherwise misuse AI systems to gain power. IFP’s brief on preventing AI sleeper agents gives one overview; there’s another in this paper on AI-enabled coups.

- Building AI tools that improve people’s ability to reason and coordinate. This could help people to understand what’s happening in terms of power concentration, and coordinate to protect their own interests. AI tools for existential security gives an overview of the area, as does our own article on AI-enhanced decision making (but with more caveats). There are more ideas here and here, and the Future of Life Foundation recently ran a fellowship on AI for human reasoning.

- Develop and advocate for policies which distribute power over AI. This is less well-scoped than the agendas above, but could include policies for sharing AI capabilities and compute more widely, transparency into AI capabilities and their use, and whistleblower protections.

You can express interest in working to reduce the risk of extreme power concentration here.26

For more ideas, you can look at the mitigations sections of these papers on AI-enabled coups, gradual disempowerment, and the intelligence curse; as well as these lists of projects on gradual disempowerment. The field is still very early stage, so a key thing to do might just be to follow the organisations and researchers doing work in the area,27 and look out for ways to get involved.

Learn more

The problem of AI-enabled power concentration:

- Power grabs

- AI-Enabled Coups: How a Small Group Could Use AI to Seize Power, by Tom Davidson, Lukas Finnveden, and Rose Hadshar

- Podcast: Tom Davidson on how AI-enabled coups could allow a tiny group to seize power

- How an AI company CEO could quietly take over the world, by Alex Kastner

- Secretly Loyal AIs: Threat Vectors and Mitigation Strategies, by Dave Bannerjee

- Economic dominance

- The intelligence curse, by Luke Drago and Rudolf Laine

- Could one country outgrow the rest of the world?, by Tom Davidson

- Gradual disempowerment, by Jan Kulveit et al (and our summary)

- AGI, Governments, and Free Societies, by Justin Bullock et al

How bad AI-enabled power concentration could be:

- AGI and Lock-in, by Lukas Finnveden, Jess Riedel, and Carl Shulman

- Our problem profile on stable totalitarianism

- Reducing long-term risks from malevolent actors, by David Althaus and Tobias Baumann

- Human Takeover Might be Worse than AI Takeover, by Tom Davidson

Some mitigations for AI-enabled power concentration:

- Law-Following AI: Designing AI Agents to Obey Human Laws, by Cullen O’Keefe et al

- Auditing language models for hidden objectives, by Samuel Marks et al

- AI tools for existential security, by Lizka Vaintrob and Owen Cotton-Barratt, or our own similar article on AI-enhanced decision making, which covers much of the same ground but explores objections to working on this area more

- The mitigations sections of the papers on AI-enabled coups, gradual disempowerment, and the intelligence curse

- Gradual Disempowerment: Concrete Research Projects, by Raymond Douglas

- The best approaches for mitigating “the intelligence curse” (or gradual disempowerment), by Ryan Greenblatt

Notes and references

- Walmart is the company with the largest revenue, at $680 billion. World GDP is $110 trillion, so Walmart makes around 0.6% of world GDP.↩

- We’re focusing on scenarios where power becomes concentrated to a small group of humans, but AI systems could also concentrate power for themselves, agentically through power-seeking or emergently through gradual disempowerment. There isn’t a clean distinction here between human and AI power concentration: many scenarios will involve some of both, and it’s not immediately obvious that one is much worse than the other. We’re scoping this article to human power concentration in particular, because there are some dynamics which are specific to human actors, and because it’s helpful to be more granular (and we already have problem profiles on forms of AI power concentration).↩

- In this survey of researchers who’d published in top AI journals:

- The aggregate forecast for the year when unaided machines can accomplish every task better and more cheaply than human workers was 2047. For the year when labour is fully automated, the aggregate forecast was 50% by 2116, though still gave substantial probability mass for before 2050 (~20%).

- The median respondent thought it was 20% likely that there would be explosive progress two years after human-level machine intelligence.↩

- You can also make a similar argument about gradual disempowerment: the same emergent dynamics which could lead to the gradual disempowerment of all humans could also lead to the disempowerment of most humans, leaving the remaining few in positions of extremely concentrated power. As the term is typically used, gradual disempowerment is highly overlapping with AI-enabled power concentration, but not the same thing:

- Gradual disempowerment includes scenarios where power is concentrated with AI systems rather than humans, and in the extreme could lead to all humans being disempowered.

- As we’re defining AI-enabled power concentration, even in the extreme case some humans would hold power. We’re also including scenarios which are more sudden and agentic, where power-seeking individuals seize power for themselves.↩

- It’s possible that as AI automates more human labour, humans will just shift to working on complementary things, as has happened with automation in the past. But if AI becomes cheaper and better than humans at most or all tasks — which is what frontier AI companies are aiming for — then this won’t be possible. And rapid automation could lead to big temporary disruptions even if human labour eventually recovers.↩

- It could also increase the value of human labour, if tasks which only humans can do become the key bottleneck on economic progress and therefore very valuable. But this might be temporary, and could still be accompanied by dramatic increases in returns to capital as it becomes easier to turn money directly into labour by running AI systems — in which case we might still see concentration of power among capital holders.↩

- AI development is already concentrated among a few companies, because it’s so expensive to build (it’s estimated that training Grok-4 cost $480 million, making it the most expensive model to date). This could get more extreme in future if development costs continue to rise, or there’s an intelligence explosion that allows one company to pull ahead substantially.↩

- Right now, companies have the most advanced AI. But as capabilities become more transformative, governments will probably seek to have more control over AI development, potentially even centralising it into a single project either domestically or internationally (there are calls for both).↩

- Another reason to expect power concentration within organisations besides automation is that as AI capabilities become more dangerous, access is likely to get more restricted. This could be a very good thing, by reducing the risk of catastrophic misuse. But if it’s done badly, it could also lead to huge capability imbalances, where only a few executives or government officials have access to the most powerful capabilities.↩

- See Haggard and Kaufman (2021) for an overview.↩

- This needn’t look like a standard military coup where an official suddenly uses the army to seize power. Experts also talk about self-coups or executive coups, where heads of state backslide all the way to dictatorship. The line between ‘this is ‘only’ backsliding’ and ‘this is an executive coup’ is blurry and political. Here we’re trying to cover any scenarios where the end result is that a small group has consolidated ultimate control over the government.↩

- We already have proof of concept that AIs can be trained with hidden objectives (but these are currently very basic and easy to detect).↩

- Detection capabilities will also improve, so it’s not clear how hard secret loyalties will be to uncover. Some reasons to think they’ll be easy to find are:

- AI could be very thoroughly tested for secret loyalties, by red-teaming their behaviour in a wide range of scenarios, and by using interpretability techniques to analyse how the models are working internally.

- You might need to train AI systems in a very particular way to make them secretly loyal, such that it’s pretty easy to spot secret loyalties by looking at the training data.

Those are arguments against the idea that there will be something fundamentally difficult about detecting secret loyalties. But even if it’s technically not too challenging, there are still reasons to think that secret loyalties might prove very hard to detect in practice:

- Auditors might not be given enough access to detect secret loyalties.

- If one company has a large capability lead, other actors might not have sophisticated enough AI to detect secret loyalties in their systems.

It’s definitely possible that secret loyalties end up being easy to defend against, but we wouldn’t bet on it.↩

- Metaculus forecasters predict a 30% chance that a G20 country fields a fully-autonomous, no human-in-the-loop lethal military AI weapon system by 2030.↩

- To give some extreme examples: 150 soldiers successfully overthrew President Léon M’Ba in Gabon in 1963, President Christophe Soglo in Dahomey was deposed by 60 troops in 1967, and only 10 soldiers executed the 1981 coup in Ghana (Bruin, 2020, p. 16).

How is it possible for such small forces to successfully take over? Singh gives a general argument that coups are coordination games, and coup plotters can succeed by preventing others from coordinating to stop them. More specifically, other forces might not intervene because of fear of bloodshed, intimidation of key personnel, political pressure, popular support or the perception of popular support, ambiguity about what’s happening until it’s too late, or inertia. If the small group is using very powerful AI, they might be able to even more successfully muddy the waters to prevent coordination or simply out-manoeuver other groups.↩

- In particular, a power grab over the US or China could be translated into world dominance, if that country also had a lead in AI development.↩

- This dynamic is discussed in much more detail in this chapter of Drago and Laine’s Intelligence Curse.↩

- Around 50% of world GDP is spent on human labour — roughly $50 trillion per year (Hickel, Hanbury Lemos and Barbour, 2024, Figure 9; World Bank, no date). Once AI surpasses humans on the vast majority of tasks, a similar fraction of GDP may be paid towards AI labour. Revenues will initially be much lower due to delays integrating AI in the economy — but AI projects could likely attract massive investment in anticipation of future revenues.

Even just automating cognitive labour might be enough to earn tens of trillions of dollars in revenue. Knowledge workers make up around 20–30% of the global labour force (Berg and Gmyrek, 2023), but are paid significantly more than manual workers.↩

- To outgrow the world, an actor would have to:

- Start out with >50% of GDP

- Be willing to sacrifice GDP in the short term (by losing out on gains from trade)

- Coordinate hard internally to prevent technological diffusion to other actors

- Not worry about setting a dangerous precedent that internal factions could follow later (i.e. get >50% resources then outgrow everyone else)↩

- The simple story here is that maybe you can send out probes faster than any follower can catch them up, and stars are defense dominant so you can hold onto them indefinitely. The actual story is a lot more complicated (what if followers can spend their time developing faster probes? Are stars actually defense dominant? What about solar systems and galaxies?), and we feel pretty uncertain here.↩

- This already happens, but more powerful AI might make it a lot worse, by:

- Making it harder to know what’s true, due to deepfakes, citation chains of AI-generated content, increasingly sophisticated bots posing as real people, or new mechanisms of epistemic confusion

- Raising the stakes, so the harms from epistemic interference get worse

- Making everything happen much faster, so it’s harder to keep up

- Restricting access to the best sense-making tools to a small number of people↩

- From other perspectives, justice and political empowerment are only instrumentally valuable, for example insofar as they prevent tyranny. If you hold this view, then provided a benevolent dictator who can permanently ensure that people have high welfare, there’s no additional need for political empowerment.↩

- Even if there are still multiple powerful actors, AI might make it possible for states to make permanently binding commitments. This could lead to scenarios where a state uses threats to extort other states to recognise its regime in perpetuity.↩

- Increasing lab infosecurity would make diffusion of AI capabilities slower, which could concentrate power somewhat. But it would also make it harder for insiders (or infiltrators) to insert secret loyalties or misuse AI to seize power. Overall, we therefore expect that infosecurity would reduce power concentration.↩

- Law-following AI also relates to the broader question of establishing rules to prevent AI misuse, discussed in this report and at more length in an appendix.↩

- The form is run by Forethought, but they are in touch with other researchers in the power concentration space and will forward on expressions of interest. They won’t reply to everyone who expresses interest, but in some cases will be able to help with funding, mentorship or other kinds of support.↩

- Organisations that have done research on this in the past or we know are interested in this problem include: Apollo Research, Forethought, Future of Life Foundation, the Future of Life Institute, the Institute for Law & AI and Redwood Research.

The authors of the papers on gradual disempowerment and the intelligence curse don’t work at those orgs, but are also very relevant people to follow.↩