Know what you’re optimising for

Table of Contents

There is (sometimes) such a thing as a free lunch

You live in a world where most people, most of the time, think of things as categorical, rather than continuous. People either agree with you or they don’t. Food is healthy or unhealthy. Your career is ‘good for the world,’ or it’s neutral, or maybe even it’s bad — but it’s only the category that matters, not the size of the benefit or harm. Ideas are wrong, or they are right. Predictions end up confirmed or falsified.

In my view, one of the central ideas of effective altruism is the realisation that ‘doing good’ is not such a binary. That as well as it mattering that we help others at all, it matters how much we help. That helping more is better than helping less, and helping a lot more is a lot better.

For me, this is also a useful framing for thinking rationally. Here, rather than ‘goodness,’ the continuous quantity is truth. The central realisation is that ideas are not simply true or false; they are all flawed attempts to model reality, and just how flawed is up for grabs. If we’re wrong, our response should not be to give up, but to try to be less wrong.

When you realise something is continuous that most people are treating as binary, this is a good indication that you’re in a situation where it’s unusually easy to achieve something you care about. Because if most people don’t see huge differences between options that you do, you can concentrate on the very best options and face little competition from others.

Sometimes the converse is also true: people may treat something as continuous, and work hard at it, despite the returns to working harder actually being very small.

An example that sticks in my mind from my time teaching maths is about how neatly work is presented. Lots of people care about neat work or good presentation, and sometimes there’s a very good reason for this. If work is messy enough that it’s difficult to read, or that the student is making mistakes caused by misreading their own writing, this is important to fix!

The problem is, the returns on neatness suddenly drop off a cliff when the work is clear enough to be easily readable, and yet some students will put huge amounts of effort into making their work look not just clear, but unnecessarily neat.

Worse still, some teachers will praise this additional effort, implying it’s a good thing that someone takes three times as long as they need to on every piece of work just to make it look nice. But it’s usually1 not — that extra time could be used for learning, or just hanging out with friends!

I remember speaking to some students who were struggling with their workload, only to discover that they were doing each piece of work twice: once to get the maths, and another to copy everything out beautifully to hand in. It broke my heart.

Even when it’s fairly normal to try really hard at something, it’s worth checking that more effort is reliably leading to more of what you care about. That is to say, there are some things you should half-ass with everything you’ve got.

Thinking about these ideas as I tried to help my students — and now as I try to help the people I advise — I’ve noticed two ideas that frequently appear in the advice I give.

- Try optimising for something.

- Know what you’re optimising for.

In the rest of this article, I describe how I think about applying these two ideas, and the sort of mistakes that I hope they can prevent. I include lots of examples, and most of these are linked to career decisions inspired by real conversations I’ve had, though none were written with a specific person in mind, and all of the names are made up.

I also try to include some more abstract mathematical intuition, made (hopefully) clearer with the addition of some pretty graphs.

At the end of the article, I try to think of ways in which the advice might not apply or be misleading, though you may well generate others as you read, and trying to do so seems like a useful exercise.

Idea #1: Consider optimising for something

You are allowed to try really hard to achieve a thing you care about, even when it’s a thing not that many people try hard to achieve — in some ways, especially in those cases. You don’t have to stop at ‘enough,’ or even at ‘lots’ — you can keep going. You can add More Dakka.

The thought of trying really hard at something feels very natural to some people, including many who I expect might find useful ideas in the rest of the article. But to many others, it feels gross, or unnatural, or in some way ‘not allowed’ — ‘tryhard’ is a term some people even use to insult others! It’s for this last reason that I framed this idea in terms of permission — I don’t think you need it, but if you found the idea off-putting, now you have permission to do it anyways.

Idea #2: Know what you’re optimising for

This idea is about being deliberate in what you’re trying hard to achieve. It’s about trying to ensure that the subject of the majority of your effort is in fact the most important thing. In some sense, like optimising at all, it’s about permission: knowing that you are allowed to realise that one thing is much more important for you to get than all of the others, and trying to get it (even if it’s not the typical thing people want).

Know what you’re optimising for is also, I suspect, often about picking only one thing at a time, even if multiple things are important. Even in cases where picking one thing doesn’t seem best, asking the question “Which one thing should I optimise for?” seems like it might produce useful insights.

People often optimise for the wrong thing

I first saw people repeatedly optimising for the wrong thing when I was teaching. Students care about many things, from status among their peers to getting good enough grades for university. Many of these things are directly rewarded by people that students interact with: parents will praise good grades; other students will let you know what they think of you; and some teachers will be fairly transparent about who they think the smart kids are (even if they try to hide it).

Importantly, though several of these things are correlated with learning, none of them are perfect indicators of actually learning. Even though most people agree to some extent that one of the major purposes of school is learning, learning has a really weak reward signal, and it’s easy to drift through school without really trying to learn.

There’s a difference between doing things that are somewhat correlated with things you want (or even doing things that you expect to lead to things you want), and trying really unusually hard to actually get what you want. Sometimes working out what you actually want can be really hard — for many, working out what one ultimately values can be a lifetime’s work. However, I’ve been frequently surprised, during my time as an advisor, by how often it’s been sufficient to just ask:

It looks like you’re trying to achieve X here. Is X really the thing you want?

The mistake of optimising for not quite the thing you want can be particularly easy to miss if the thing is useful in general, but in this instance is not useful for you. For one thing, it’s hard to internally notice without specifically looking for it. But you’re also less likely to have others point out this mistake, because things that are useful in general seem more ‘normal’ to have as a goal. For instance, appearing high status seems pretty useful, and it’s a goal that many people have to some extent, so who’s going to stop and ask you whether you really endorse playing as many status games as you are?

Perhaps a more relevant example is that I often see (usually young) effective altruists optimising for impact per unit of time, rather than for the total impact they expect to have over their career. They ask themselves what the most impactful thing they can do right now is, and then do that. This often works well, and there are many worse heuristics to use. Unfortunately, it’s not always the case that trying to do the very best thing right now puts you in the best position to do the most good overall.

People seem to accept this when it comes to going to university. Choosing to do an undergraduate degree is to some extent like choosing to take a negative salary job — which usually doesn’t produce any useful output to others — purely to learn a lot and set yourself up well to achieve things later. For many people, this is a great idea! But then something strange happens when people graduate. For an altruist, taking a role in a for-profit company where you’ll gain a whole bunch of useful skills can look very unattractive, as you won’t be having any direct impact. Taking a salary hit for an opportunity to learn a ton also doesn’t look good (that is, unless the opportunity is called ‘grad school,’ in which case it looks fine again). Neither of these strategies are necessarily best, but they are at least worth considering! The lost impact or salary at the outset might be made up for many times over if you’re able to access more impactful opportunities later.

The law of equal and opposite advice applies in many places, and this is one of them. Just as you might make the mistake of under-investing in yourself, you can also stay in the ‘building up to have a big impact later’ phase for too long. Someone I advised not too long ago referred to themself as “an option value addict,” which I thought was a great way to frame this idea. While the idea of option value — that it can be useful to preserve your ability to choose something later — is a really valuable one, it’s only valuable to keep options that you actually have some chance of choosing. The smaller the chance that you ever take a particular option, the less valuable it is to preserve it — so thinking about how likely you personally are to use it ends up being important.

For example, it might be worthwhile for some people to keep an extremely low profile on all forms of social media in case a spicy social media presence prevents them from later working for an intelligence agency or running for office. But if you have absolutely no intention of ever working in government, this reason doesn’t apply to you! (There are, of course, other reasons one might want to limit social media exposure.)

Trying to optimise for too many things can lead to optimising for nothing in particular

As well as optimising for the wrong things, I often speak to people who are shooting for too many things at once. This typically plays out in one of two ways:

- People try to optimise for so many things that they don’t end up making progress on any.

- People just don’t optimise at all — because when so many things seem important, where do you even start?

In both cases, this often ends up with people trying to find an option that looks at least kind-of good according to multiple different criteria. Doing well on many uncorrelated criteria is pretty hard.2 This often leads to only one option being considered… and that option not looking great.

What might this look like?

The examples below have been inspired by conversations I’ve had. Each involves a hypothetical person describing an option which seems pretty good. It might even be the best option they have. But all of these pretty good options follow the pattern of ‘this thing looks good for many different reasons’ — and ‘looks good for many reasons’ misses the importance of scale: that doing much, much better in one way is often better than doing a little better in several ways at the same time. The people in the examples would benefit from considering what their decision would look like if they picked one source of value, and tried to get as much of that as possible.

Alex

If I join this cleantech startup, I will be contributing to the fight against climate change. It’s also a startup, so there’s some chance it will go really well — so this is also an earning-to-give strategy, and I might learn some things by being there.

- If I’m hoping to pursue a ‘hits-based’ earning-to-give strategy as a startup founder or early-stage employee, almost all the expected value is going to come from the outcomes where the project really takes off. If I look around the startup space for other options, how likely does it seem that this is the one that will take off? Can I find a much better opportunity if I drop the requirement that it has to be in cleantech?

- When I really reflect on which causes seem important, I realise that I’m quite likely to make my donations to reducing global catastrophic biological risks, rather than climate charities. There’s a lot of need for founders in the biosecurity space, and my skills and earnings won’t be that useful in the next few years, so maybe the learning value from being part of an early-stage startup is the most important consideration here. Does the cleantech startup look best on that basis, or is there somewhere else I might be able to learn much more, even if the primary motive of the founders is profit rather than climate change?

Luisa

If I do this data science in healthcare internship, I’ll learn some useful machine learning skills, and I might be able to directly contribute to reducing harm from heart disease.

- Developing my machine learning skills seems like the most important thing for me to focus on, given what I want to work on after graduating. It’s not clear that this internship is going to be particularly helpful — I’m probably just going to end up cleaning data. I don’t learn well without structure though. Could I find someone to supervise or mentor me through a machine learning project?

- I’m pretty sure I’ll learn loads during summer; I’ve done really well at teaching myself programming so far and would probably learn even more if I didn’t do the internship. But I don’t want to have to move back into my parents’ house in the middle of nowhere where I’ll be miserable, and the pay from the internship will mean I can afford to stay in a city, see my friends, and keep motivated. If the main thing I’m getting from the internship is money, can I apply for a grant? Or can I find something shorter which will still pay me enough, or something where I’ll be writing more code even if it’s not in healthcare?

Benjamin

This role isn’t directly relevant to the cause I think is most important, but it’s still helping somewhat, and it’s fairly well paid so I can also contribute with my donations.

- If I just took the highest-salary job I could, how much more would I be able to donate? Would that do more good than my direct work in my current role? I think my donations are directly saving a lot of lives, so I should at least run the numbers.

- I’m giving away a decent fraction of my salary anyway, so I’m happy to live on less than this job is giving me. Did I restrict my options too much by looking for such a high salary? I should look at whether there are any jobs I could take where I’d be able to do much more good directly than the total of my current work and donations are doing now.

When facing a situation with multiple potential sources of value, you might be able to get outsized gains by just pushing really hard on one of them. In particular, it’s possible to get gains so big that they more than outweigh losses elsewhere.

It’s not always the case that you can completely trade off different good things against each other — many people, for example, want to have at least some interest in their work. But it is sometimes the case, and it’s worth noticing when you’re in one of those situations. In particular, if the different good things you’re achieving are all roughly described as ‘positive effects on the world,’ you can estimate the size of the effects and see how they trade off against each other. What matters is that you’re doing good, not how you’re doing it. Of course, be careful not to take that last part too far.

The ‘alternative framings’ in the examples above all replace optimising for nothing in particular with just optimising for one thing. The other things either got dropped entirely, or were only satisficed,3 rather than optimised for. This isn’t an accident. Picking one thing forces you to be deliberate about which thing you shoot for, and it makes it seem possible to actually optimise. I think those benefits alone are enough to at least consider just picking one thing.

But I actually suspect that something even stronger is true: often just having a single goal is best.

The intuition here is that when you value things differently to the population average, your best options are likely to be skewed towards the things you care relatively more about. Markets are fairly efficient for average preferences, but when your preferences are different to the average, you might find big inefficiencies. For example, if you’re househunting and you absolutely love cooking but never work from home, it’s worth looking for places that have unusually big kitchens compared to the size of the other rooms. Most people are willing to pay more for bigger rooms, or a home office — if you don’t need those things, don’t pay for them!

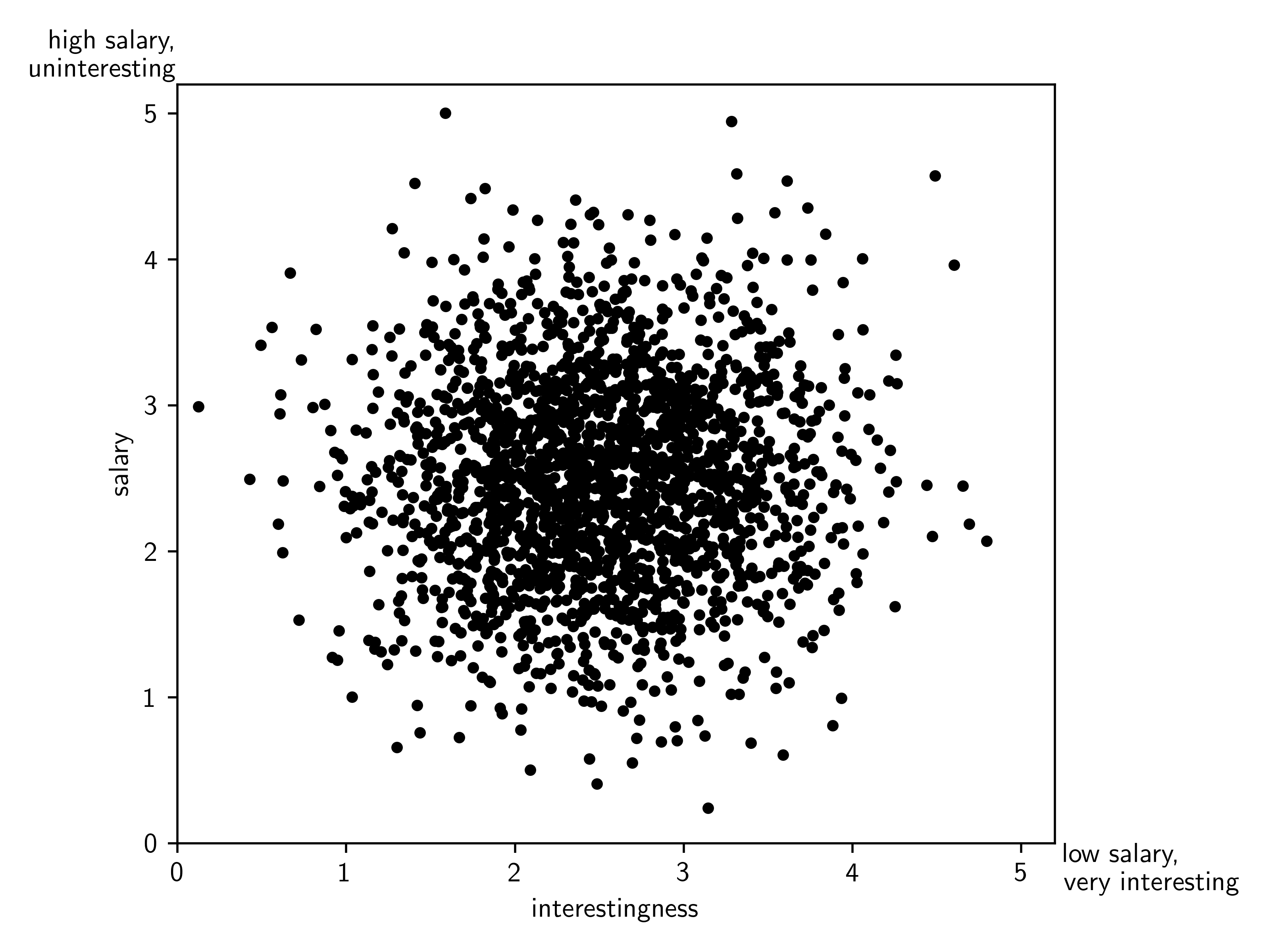

Let’s sketch some graphs to try to see what’s going on here. Consider the case where you care about two things — let’s say salary and interestingness. (Often you’ll care about more than two things, but 2D plots are easier to sketch, and I suspect that the effect I sketch below is even stronger in higher dimensions.) You might expect the job market to look something like Figure 1:

Let’s assume that the average person cares equally about salary and interestingness, and rates them by just adding up the two scores. When this is the case, we should expect that higher-salaried jobs that are more interesting will be harder to get.

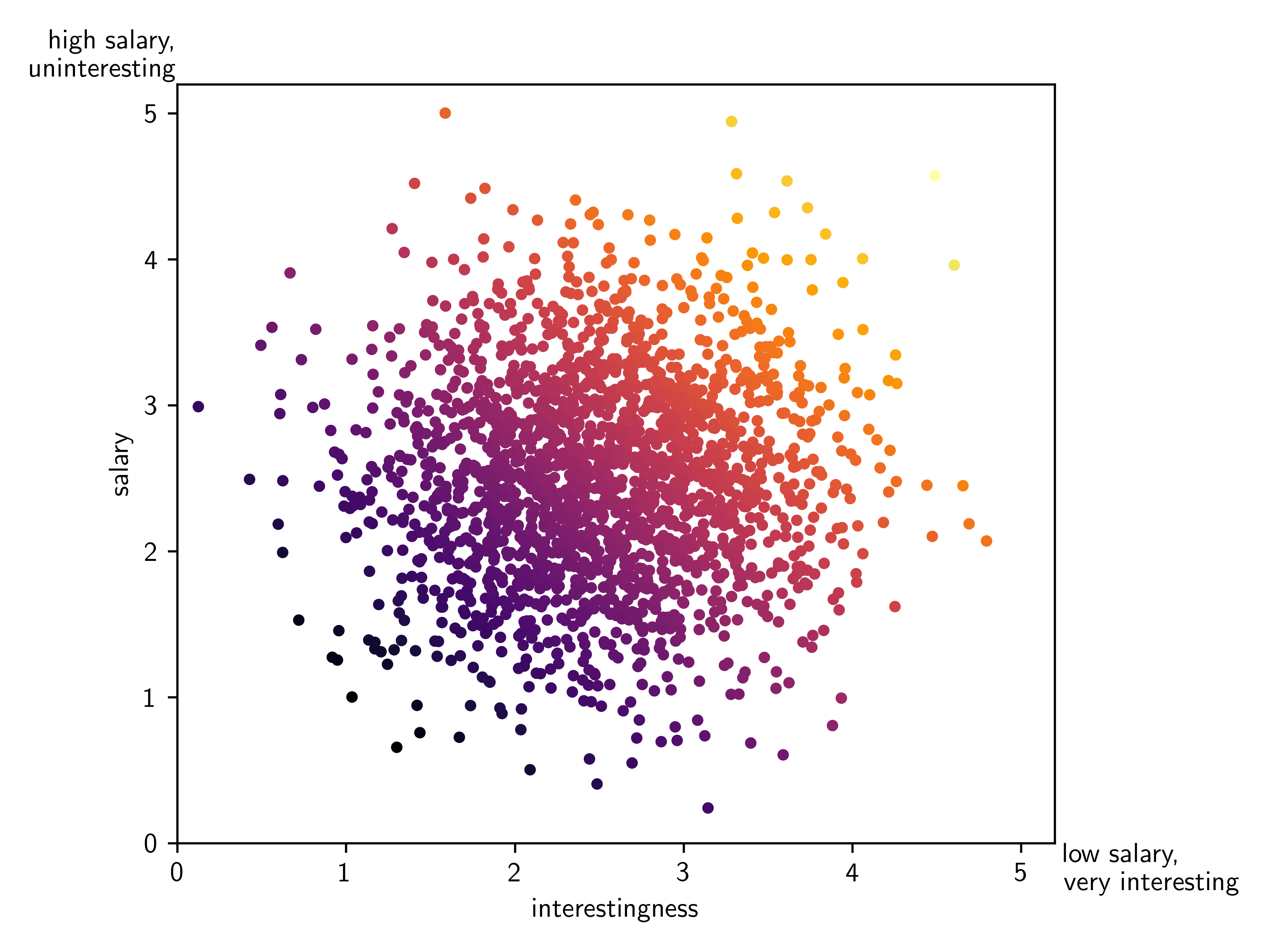

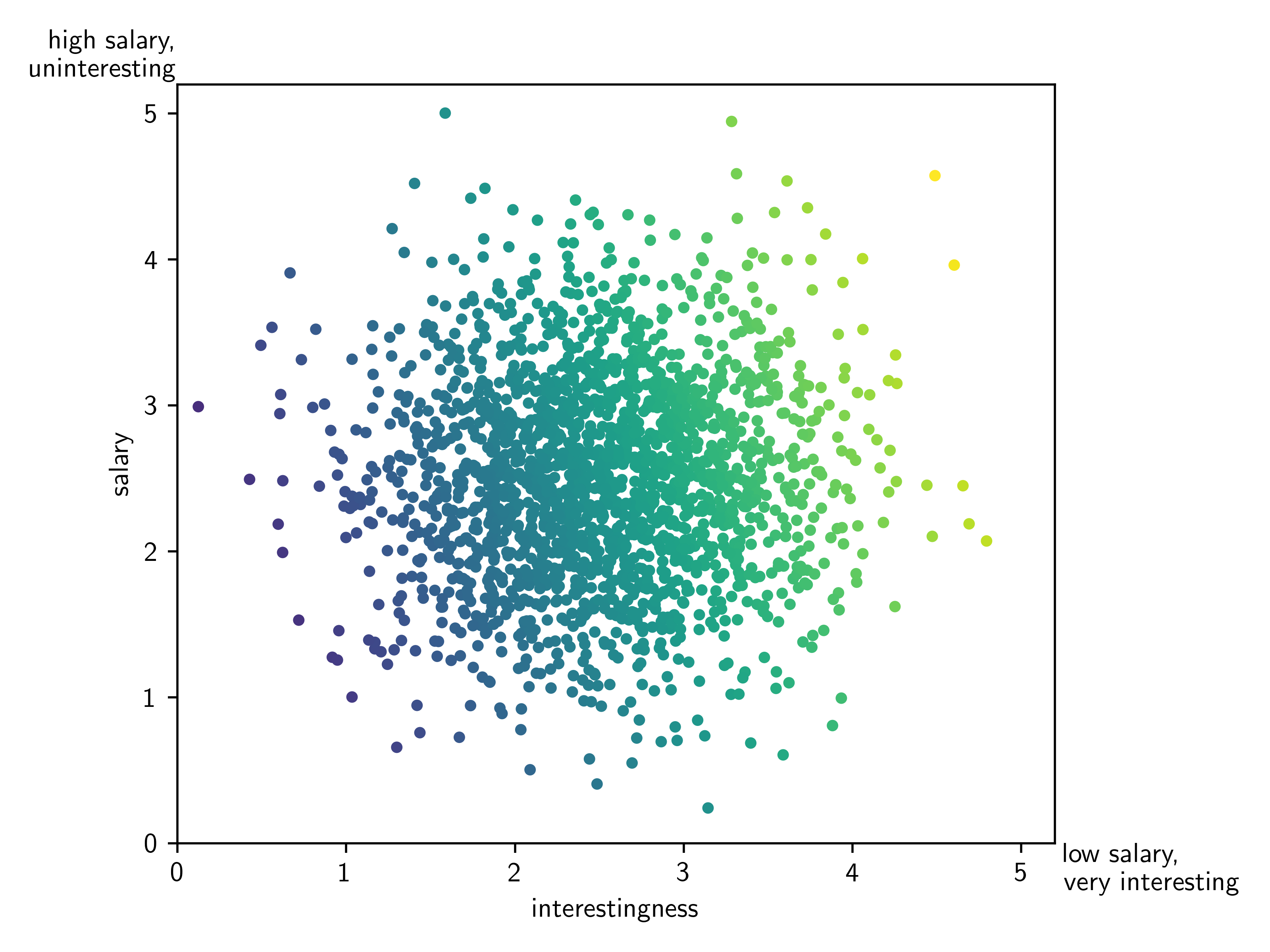

In Figure 2, I’ve colour coded easy jobs to get as black/purple and harder jobs to get as orange/yellow below. But what if I care much more about my job being interesting than it paying well? In this case, the best jobs for me won’t be quite the same as the hardest for me to get. I’ve shown this preference in Figure 3 by colour coding a different plot from bright yellow (perfect for me) to dark purple (terrible for me). I assumed that I still cared about salary, but that interest was three times as important — so to rank the jobs, I multiplied the interest score by three before adding salary.

I want to look for jobs that are easier for me to get (darker on Figure 2), and that I’ll actually want (lighter on Figure 3). The easiest jobs for me to get are in the bottom left, which doesn’t help much, as I don’t want these. The jobs I want most are in the top right, which also doesn’t help much as these are hardest to get. If my theory is correct, I should get the best tradeoffs between these two things by focusing hard on the thing I care more about than average (interest), while not worrying as much about the thing I care less about than average (salary). This would tell me to look first in the bottom right of the graph.

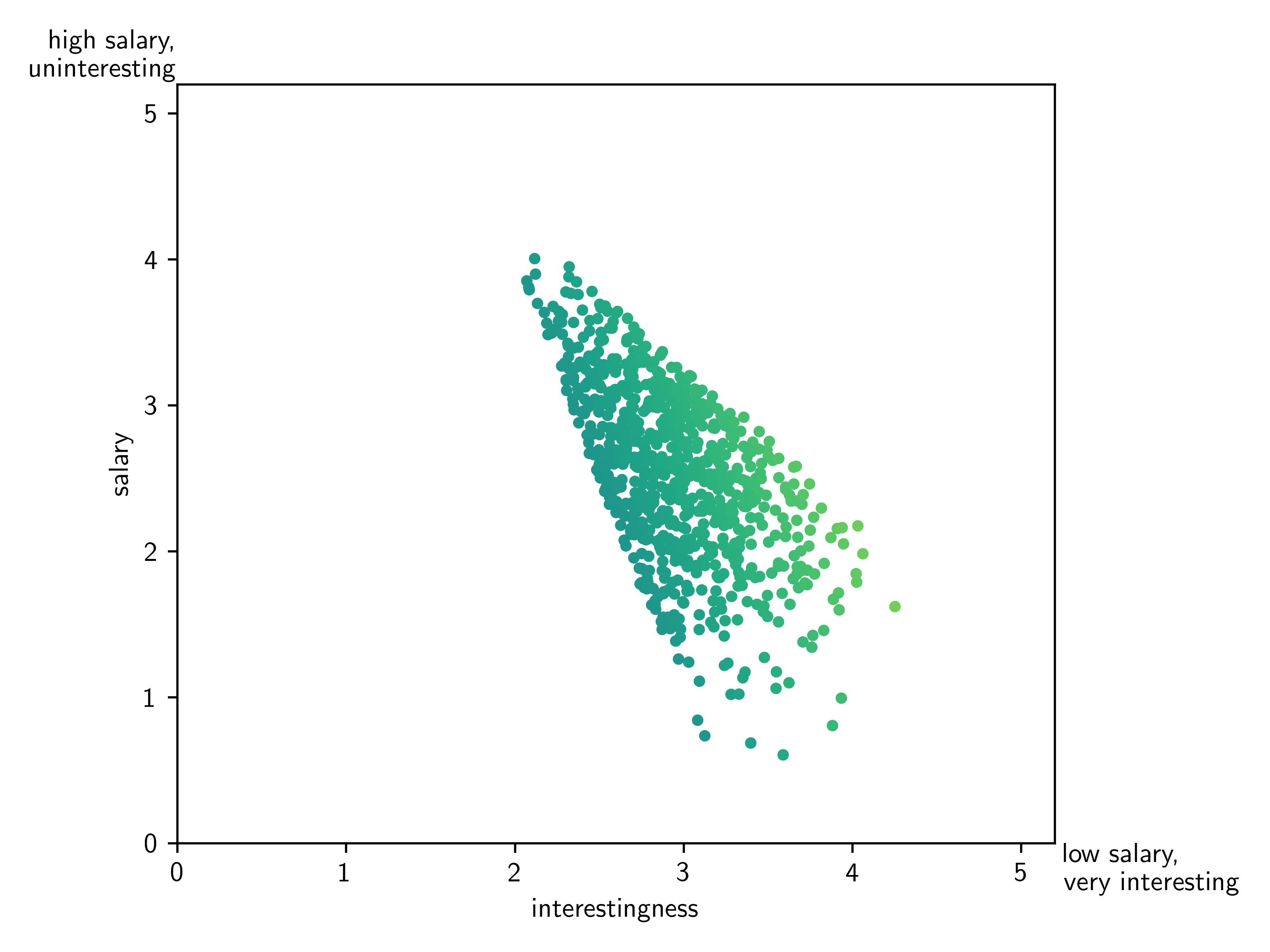

It’s a little hard to tell from just these two figures exactly how well the theory is doing, so let’s make things a bit easier to see in Figure 4 below. First, I removed the top 10% most popular jobs among the general public, to represent some jobs being competitive enough to not even be worth trying. I then also removed the bottom 50% of the jobs according to my preferences, to represent wanting to look for something better than average. Both of these cutoffs are arbitrary, but the conclusion doesn’t change when you pick different ones.

As expected, the best-looking options I’ll actually be able to get look like very interesting, low-salary jobs.

In practice, all of the tradeoffs above will be much less clean. Preferences about different options probably shouldn’t be linear, for example, certainly not in the case of salary. Despite all this, the conclusion remains that if your preferences are in some way different from the average, some of the best places to look to exploit the differences are the extremes.

When do I expect this not to apply?

Multiplicative factors

In the sorts of situations I describe above, the total value tends to come from the values from each different consideration being added up: my job being interesting makes me a bit happier, and so does being paid more; donating money to effective charities saves lives, and so does working for one of those charities. In these cases, less of one thing pretty directly gets traded for more of another. Even in these cases, it can still be worth getting to some minimum level,3 if you get most of the gains from getting to that level and/or it’s easy.

Sometimes though, success looks more like a bunch of factors multiplied together than a bunch of things added together. When this is the case, it becomes really important that none of those factors end up getting set too low, which can be catastrophic.

In my view, the most important example of something that can be a multiplier on everything else you’re doing is personal health and wellbeing, especially when it is in danger of dropping below a certain level. Burnout is already a big risk when you’re optimising for doing as much as possible to help, especially among people who really care about others. In fact, one of my biggest concerns in writing this piece is that it might make this risk higher.

In some sense, we can frame this problem as a mistake of optimising for the wrong thing: impact right now instead of impact over the long run. But on this topic, the thing I care most about is not what it says about optimisation — I care most that you take care of yourself as your number one priority. These resources provide useful perspectives on this risk, as well as some ideas for how to reduce it:

- I burnt out at EAG. Let’s talk about it

- Aiming for the minimum of self-care is dangerous

- Podcast: Having a successful career with depression, anxiety, and imposter syndrome (and also see the links in the show notes for this episode)

Very good might be good enough

You’ll often find that as you keep trying to push the envelope further, it gets harder and harder to make progress. At some point then, even after you’ve seen substantial gains from deciding to optimise at all, you may reach a point where effort on the most important thing is going to pay off less than effort on something else.

This might happen because there are fewer and fewer people who you can learn from. It could be that you are in fact now making much fewer mistakes in your efforts, and the fewer mistakes you make, the harder it is to catch and eliminate them. Maybe it’s just that you’re starting to enter the domain of people who are really trying, and competition is heating up. Whatever the reason is, there’s a chance that this is the time to pick a second thing, and push on that too. In particular, when it comes to personal skill development, not only can it be easier to get extremely good at two things than truly world-class at one, in this case your skill set might look quite special.

Next steps

People who know what they are optimising for might ask themselves things like:

- Is what I’m trying to achieve in this situation the right thing?

- Am I trying to achieve multiple things at once? Is that the best strategy?

- Does the thing I’m trying to achieve actually lead to something I want?

- What would it look like if I focused on the most important thing and dropped the others?

It might be worth thinking about some aspect of your life, and ask yourself those questions now. Did one work particularly well, or can you think of an alternative question that works better for you?

After reading this article, you may well think that this kind of mindset isn’t well-suited to the way you think. If that’s the case, that’s fine! Hopefully you now at least have a different perspective you can look at some decisions with. Even if it seems unlikely you’ll use it often, it might shed some light on decisions made by people like me.

Notes and references

- Other reasons for neat work

I do want to note that it isn’t always the case that students being extremely neat on homework is a simple mistake that they are making. I did teach a handful of people who just really really liked calligraphy, bullet-journaling, etc., and considered the practice of making their beautiful notes a fun and creative pastime. This is obviously fine; people should choose to spend their leisure time however they like.In some other cases, the reason behind the neatness was a more general difficulty with perfectionism, which is much harder to deal with than simply being told to optimise properly. Ideally such students will get help with this if they need to, but it seems worth saying that them putting loads of effort into neatness doesn’t make them stupid.↩

- Looking good for multiple reasons

The reason it’s so hard to find things that look good for multiple reasons is that, if those reasons aren’t correlated, you have to ‘get lucky’ for each new reason you add. If you’re only considering one thing, half of your options will be above the median. But if you care about four (uncorrelated) things, considering only things which seem above median in all four respects will reduce the number of options by a factor of 16. The more strongly correlated different criteria are, the easier it is to find options that do well on all of them — the effect still appears, just a bit more slowly.Realising how rare it is that multiple uncorrelated things all point in the same direction is actually a useful enough idea that there have been entire articles written about it. One example, from a completely different context, discusses how policy debates should not appear one-sided.↩

- Go as far as you need, then no further

If you care about multiple things, even if one of them is clearly the most important, the importance of all the others won’t necessarily drop to zero. In the case that several of the things are ways of achieving a single outcome (such as impact), maybe they might, but in general things won’t trade off perfectly. When they don’t, and you need some minimum level of several different things, a successful strategy will look like working out how much of each thing is necessary, and aiming to achieve that much, and not much more.When looking for a job, it might be the case that salary, location, and respectability all work somewhat like this. For example, you might:

- Need to earn enough to live comfortably, but beyond that salary matters little.

- Want to live in a particular city, but be happy to commute anywhere you can get by public transport or bicycle.

- Want to tell your parents what you do without being ashamed of it, but that’s roughly the level at which you’ll discuss your work.

In these sorts of cases, approaching the criteria as binary makes a lot of sense. You have some requirements you want to satisfy, but beyond that point gain little from trying to push them further.↩