80,000 Hours Annual Review – December 2018

NOTE: This piece is now out of date. More current information on our plans and impact can be found on our Evaluations page.

This annual review summarises our annual impact evaluation, and outlines our progress, plans, weaknesses and fundraising needs. It’s supplemented by a more detailed document that acts as a (less polished) appendix adding more detail to each section. Both documents were initially prepared in Dec 2018. We delayed their release until we heard back from some of our largest donors so that other stakeholders would be fully informed about our funding situation before we asked for their support. Except where otherwise stated, we haven’t updated the review with data from 2019 so empirical claims are generally “as of December 2018.” You can also see a glossary of key terms used in the reviews. You can find our previous evaluations here.

What does 80,000 Hours do?

80,000 Hours aims to solve the most pressing skill bottlenecks in the world’s most pressing problems.

We do this by carrying out research to identify the careers that best solve these problems, and using this research to provide free online content and in-person support. Our work is especially aimed at helping talented graduates aged 20-35 enter higher-impact careers.

The content aims to attract people who might be able to solve these bottlenecks and help them find new high-impact options. The in-person support aims to identify promising people and help them enter paths that are a good fit for them by providing advice, introductions and placements into specific positions.

Currently, the problems we’re most focused on are the areas listed here. They involve issues that help improve the long-term future and ‘meta’ strategies for helping, namely: positively shaping the development of artificial intelligence, biorisk reduction, global priorities research, building effective altruism, and improving institutional decision-making. Within these problem areas, we’re most focused on enabling people to enter our ‘priority paths‘, such as AI policy, technical AI safety research, and global priorities research.

We think that progress in our priority areas is most constrained by the skill bottlenecks in our priority paths and is less constrained by funding. As the main organisation whose core focus is addressing these bottlenecks, 80,000 Hours can play a major role in solving these problems.

We measure our impact by tracking the number of ‘plan changes’ we cause — people who change their careers into higher-impact paths due, at least in part, to our advice. We rate the plan changes 1/10/100/1000 depending on the expected increase in counterfactual impact resulting from our advice. Successful shifts into our priority paths where we played an important role are generally counted as ‘rated-10’ plan changes or higher.

Currently, our focus is on building a reproducible and scalable process for producing rated-10 or higher plan changes, in which our content tells people about the priority paths, and the in-person team helps the best-suited people to enter them by providing advice on their plans, introductions and placement into specific jobs.

Table of Contents

- 1 What does 80,000 Hours do?

- 2 Progress over 2018

- 3 Impact and plan changes

- 4 Historical cost-effectiveness

- 5 Why didn’t IASPC points grow in 2018?

- 6 There’s strong demand from top candidates for increased advising

- 7 A 3-year expansion plan

- 8 Weaknesses of 80,000 Hours and risks of expansion

- 8.1 The online content might not appeal to the right people or it might put them off effective altruism

- 8.2 It might be bad to grow the communities focused on our priority problems

- 8.3 We might not be able to find enough tier 1 applicants

- 8.4 It’s hard to measure and attribute the impact of our programmes

- 8.5 We could be overestimating the value of different career paths, especially junior roles

- 8.6 There is something higher priority for the team to work on than hiring

- 8.7 Other weaknesses might prevent us from executing on our plans

- 8.8 We may not be able to hire sufficiently skilled staff

- 8.9 Summing up

- 9 Priorities for 2019

- 10 Fundraising targets

- 11 Want to see more detail on what we’ve covered in this review?

Progress over 2018

Strategic progress

We’ve tracked over 130 rated-10 plan changes over our history, so we think our programmes can reliably produce this level of plan change.

Over 2018, we decided to focus on producing more rated-100 plan changes, which involve larger shifts into more senior positions, where we estimate they’ll approximately result in 10-times as much counterfactual impact.

Typically, when we ask donors and researchers in the community to place a number on the value of a 1-3 year speed up into one of these positions, they estimate these kinds of shifts are equivalent to over $1m in additional donations by the community. There are many issues with this method, but if our rated-100 plan changes indeed involve a speed up of this magnitude, it suggests they have value to the community of around this level.

We recorded ten new rated-100 plan changes this year, compared to ten over our entire previous history since 2011. About half of these seem to be significantly driven by content and in-person advice that we think is similar to our existing programmes (as opposed to personal contact with our founders, a source of impact which may not scale as rapidly with marginal funding).

These include managers at key organisations in the community, and several up-and-coming researchers who might be able to make key contributions in their field. What follows are some examples of plan changes of this kind from recent years.

Note that the efforts of many other people were necessary for these plan changes. For example, 80,000 Hours often contributes to a plan change by suggesting a potential career path to someone during advising and then introducing the advisee to experts within that path who then provide additional guidance. This means 80,000 Hours is only partially responsible for the increase in impact described in the paragraphs below even in cases where we were counterfactually necessary for the change to occur. We explain more caveats later.

People in the field have told us Cullen is one of the most promising young researchers in long-term AI policy. Cullen works part time at the Center for the Governance of AI at the Future of Humanity Institute (FHI) in Oxford and intends to work as a Research Scientist in AI Policy at OpenAI after they finish their law degree at Harvard later this year. Before engaging with 80,000 Hours, Cullen was already interested in effective altruism, but was planning to earn to give in corporate law or to work on environmental or prison law. Cullen applied for one-on-one advice in 2017, during which Peter McIntyre pointed out that AI policy could be a good fit. He introduced Cullen to several people in the field, which led to an internship and then a job offer from the Center. We and Cullen both think it’s quite unlikely that they would be on this path without 80,000 Hours.1

Another example from the last two years is Cassidy, who now works in biorisk at FHI’s Research Scholars Programme, while undertaking an Open Phil funded DPhil at Oxford. Cassidy worked as a medical doctor for four years before coming across the 80,000 Hours career profile on medicine, when she was googling how to have more impact with her career. After switching from medicine into public health, and getting involved in local effective altruism events, she received advice on work in biosecurity from Peter and Brenton, who helped her think through her options and connected her with FHI. We and Cassidy both think it’s unlikely she’d be at FHI or studying the DPhil without 80,000 Hours. Our best guess is that in our absence she would not have switched to working on biorisk for (at least) several years.

Michael Page found out about effective altruism through media coverage about earning to give, and later decided to switch out of earning to give in law due to our article on talent gaps. This led him to help restructure CEA while working there as a manager. He then became an AI Policy and Ethics Advisor at OpenAI, and is now a research fellow at CSET, a new think tank focused on AI policy. He estimated that he entered direct work two years earlier (in expectation) due to 80,000 Hours.

With many of our plan changes, there’s a significance chance they would have happened without us due to other groups in the community or even absent the community’s help at all. Even in cases where we did cause a shift, it’s often the case that they still would have later ended up on the same path, so we only caused them to speed up their transition to higher-impact work. We try to adjust for these possibilities in our metrics. Typically we adjust both for the probability that we were not counterfactually responsible for the change at all as well as the probability that (even if we did cause the change) the person would later have shifted into an equally high impact role (the adjustment can be a reduction of 80% or higher but can also be 20% or lower). Even with this assumption, we think these kinds of plan changes are plausibly worth a great deal to the community.

It’s hard to be confident in our impact in any particular case, but we think if the examples are considered as a group, they become convincing. We give more examples in the full document, and can provide more detail to larger donors.

The additional examples of rated-100 plan changes we’ve recorded this year mean we’ve become more confident that our current programmes can produce both rated-10 and rated-100 changes, which is likely our most important strategic progress this year.

Progress with our programmes

Turning to how we allocated team time in 2018, our main focus over the year was improving the ability of our programmes to produce rated-100 plan changes in the future.

One priority to this end was to attract more readers who have a good chance at entering a priority path, and are highly focused on social impact. We operationalise these readers as ‘tier 1’ applicants to our one-on-one advising programme (formerly called ‘coaching’).

A typical tier 1 applicant might have studied computer science at a global top 20 university and have read our material about AI safety, and want our help switching into a relevant graduate programme. Some of the more impressive tier 1 applicants we advised in 2018 included an economics post-doc at a top school, someone who topped their Oxford class in maths and philosophy while being class president, and two tenured professors.

An important issue we’re facing is that we think our current career guide is too basic to appeal to many of these readers, and not in-depth enough to get them up-to-speed. We’re additionally worried that our older content’s tone might be off-putting to this audience.

For this reason, our top priority within online content this year was improving the tone, nuance, and complexity of our content and drafting new core content that is more appealing to tier 1 applicants. We think we made significant progress, as outlined below.

However, we had well under one full-time equivalent staff member writing articles, so there are still many changes we’d like to make to the website. We’re concerned that much of our online written content still isn’t sufficiently appealing to these users and addressing this issue remains our top priority within our online content.

Our main online content accomplishments in 2018 were:

- We released 34 podcast episodes, growing from 4,000 to 15,000 subscribers this year. We think the podcast is at the right level for the ‘tier 1’ audience because many people who previously made rated-10+ plan changes or who are active in the effective altruism community have told us they’re fans and find it really useful. The average listener who starts an episode listens to over half of it, despite many being 2-3 hours long. We think building this audience of 15,000 people — who have often listened to tens of hours of detailed content — will greatly expand the number of tier 1 advising applicants in future years; and we think the podcast is one of the best ways to introduce people to effective altruism right now.

- With a similar aim, we also prepared half of a new ‘key ideas’ series and started work on a site redesign, which will replace the career guide as the main introduction to 80,000 Hours. As part of this, we released pages presenting our priority areas and priority paths, which are our most important advice. We also produced new write-ups of three priority paths: operations management, China specialists and AI policy, and an article on unintended harm.

We greatly improved the job board, which now receives 20,000 views per month and has already led to several placements in our recommended organisations, including at DeepMind, the Center for the Governance of AI, and Open Philanthropy. This could mean we’re now able to cause rated-10+ plan changes with only online content, which we’ve not been able to do in the past.

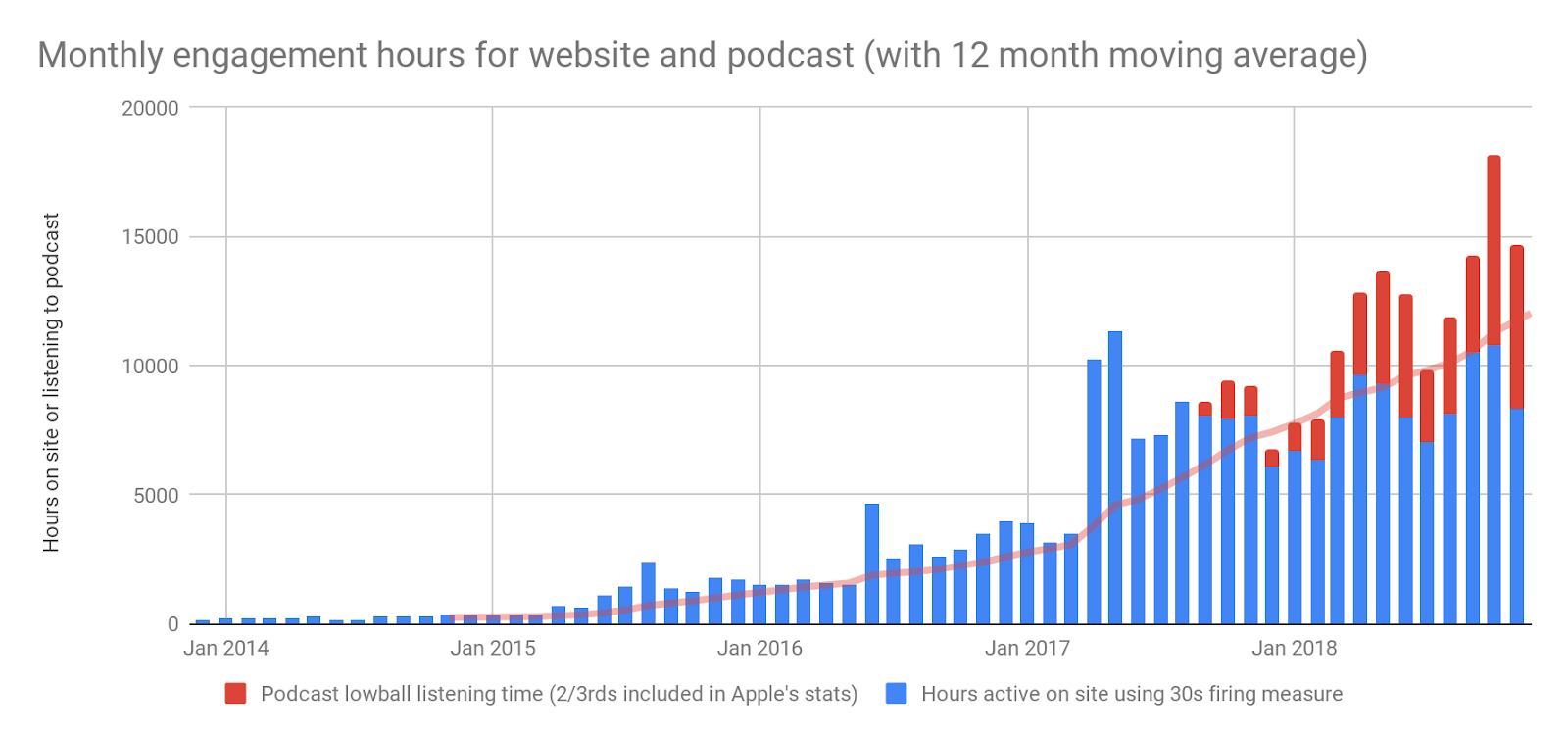

In total we released 58 pieces of content, listed here. Web traffic stayed constant at 1.6 million unique visitors, but monthly engagement time rose 60% due to high average engagement time with the podcast.

While doing this, we also improved our research. In particular, we learned lots of details about how to enter the priority paths, what the best sub-options are, and who is a good fit — we think these kinds of questions are the most important area to improve our understanding right now. As one example, we learned about the best entry routes into ML safety engineering and who is a good fit.

We’ve also re-evaluated several aspects of our core advice, such as how much to explore and build career capital early in your career, which we’ll write about in the key ideas series next year.

To get rated-10+ plan changes, we’ve found our most promising readers almost always require some kind of in-person contact. So, in addition to getting more readers, we continued to operate and improve our in-person programmes:

- We continued our experiments with specialist advising in AI policy and headhunting, which we expect are as effective or more effective than regular advising for generating rated-10+ plan changes (though we only have preliminary data to show this).

We had 3,800 sign-ups to our advising wait list despite not actively promoting it, making the one-on-one advice highly oversubscribed.

We delivered one-on-one advice to 217 people, which continues to receive very positive feedback with about 80% saying they would recommend it. We think it’s roughly as effective as last year, and likely more effective than advising 2014-2016, though it’s hard to measure over short time periods.

We also invested in expanding the capacity of the team. We hired Michelle Hutchinson as an advisor (what we used to call a ‘career coach’) and Howie Lempel as a strategy researcher. The total team grew 35% from 9.3 to 12.6 full-time equivalents. We also appointed five team leads, who are now in charge of hiring and managing the rest of the team, which gives us much more management capacity for hiring next year. We made many other improvements to operations and internal systems.

Impact and plan changes

Example plan changes

In addition to the three short examples in the section above (Cullen, Cassidy and Michael Page), we give four more examples in the full document. You can also see some older examples in our 2016 annual review.

Plan change totals

We categorise the plan changes into ‘buckets’ labelled 1/10/100/1000. This year, we also started to track negative plan changes when we made someone’s career worse or they had a negative impact.

The ratings aim to approximately correspond to how much counterfactual impact we expect will result from 80,000 Hours’ contribution to the shift. This depends on (1) how likely the change was to happen otherwise (2) the amount by which their impact increased (or decreased) compared to what they would have done in the counterfactual in which 80,000 Hours doesn’t exist. We update the ratings over time as we learn more. In particular, if we find out that someone doesn’t follow through with an intended shift, it’ll be down rated.

Note that all of the rated-100 plan changes, and most of those rated-10, are focused on global catastrophic risks or ‘meta’ problem areas. We have more description of what the typical plan changes involve and how they come about in the full document.

Here is our data on number of plan changes broken out by rating:

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rated 1 | 13 | 57 | 144 | 653 | 632 | 487 | 1986 |

| NA | 338% | 153% | 353% | -3% | -23% | ||

| Rated 10 | 8 | 11 | 10 | 16 | 50 | 38 | 133 |

| NA | 38% | -9% | 60% | 213% | -24% | ||

| Rated 100 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 10 | 20 |

| NA | NA | 300% | -25% | -33% | 400% | ||

| Rated 1000 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | -100% | ||

| Rated 10 in previous years, but downgraded | 0 | 0 | 0 | -2 | 0 | -7 | -9 |

| Rated -1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -4 | -4 |

| Rated -10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -1 | 0 | 0 | -1 |

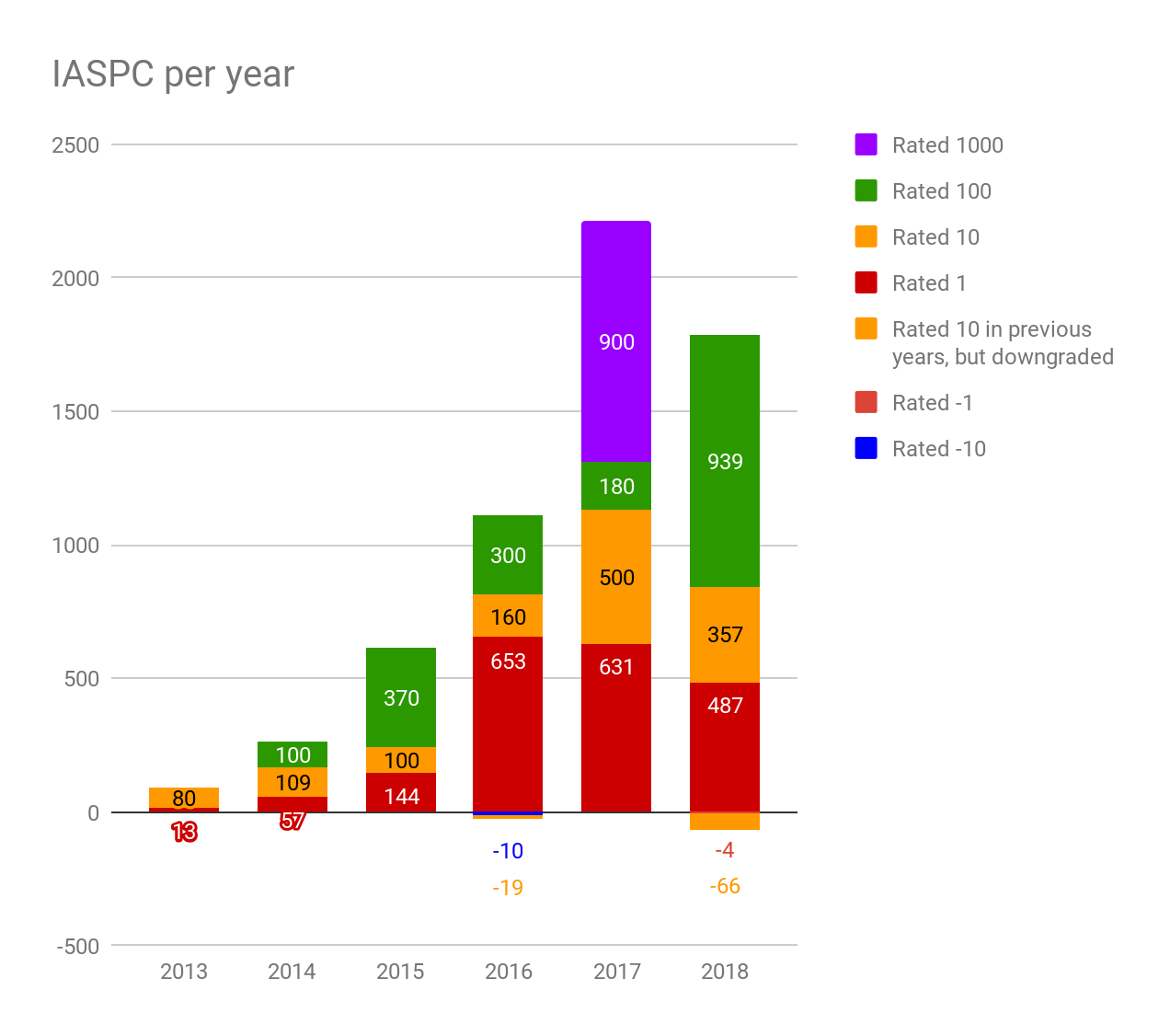

If we weight the plan changes by the category label, we call the total the number of ‘impact-adjusted significant plan change’ (IASPC) points. If we chart the annual change, we get the following growth chart:

Note that we count the change in points each year, so if a plan change were rated-100 in 2016, and then rated-1000 in 2017, we’d record +900 points in 2017. This is why the amounts are not multiples of 10. (This means the annual totals reflect the change in all-time impact measured that year, rather than the impact attributable to that year. We do this to keep the metric simple — it’s challenging to attribute the impact of plan changes to specific years.)

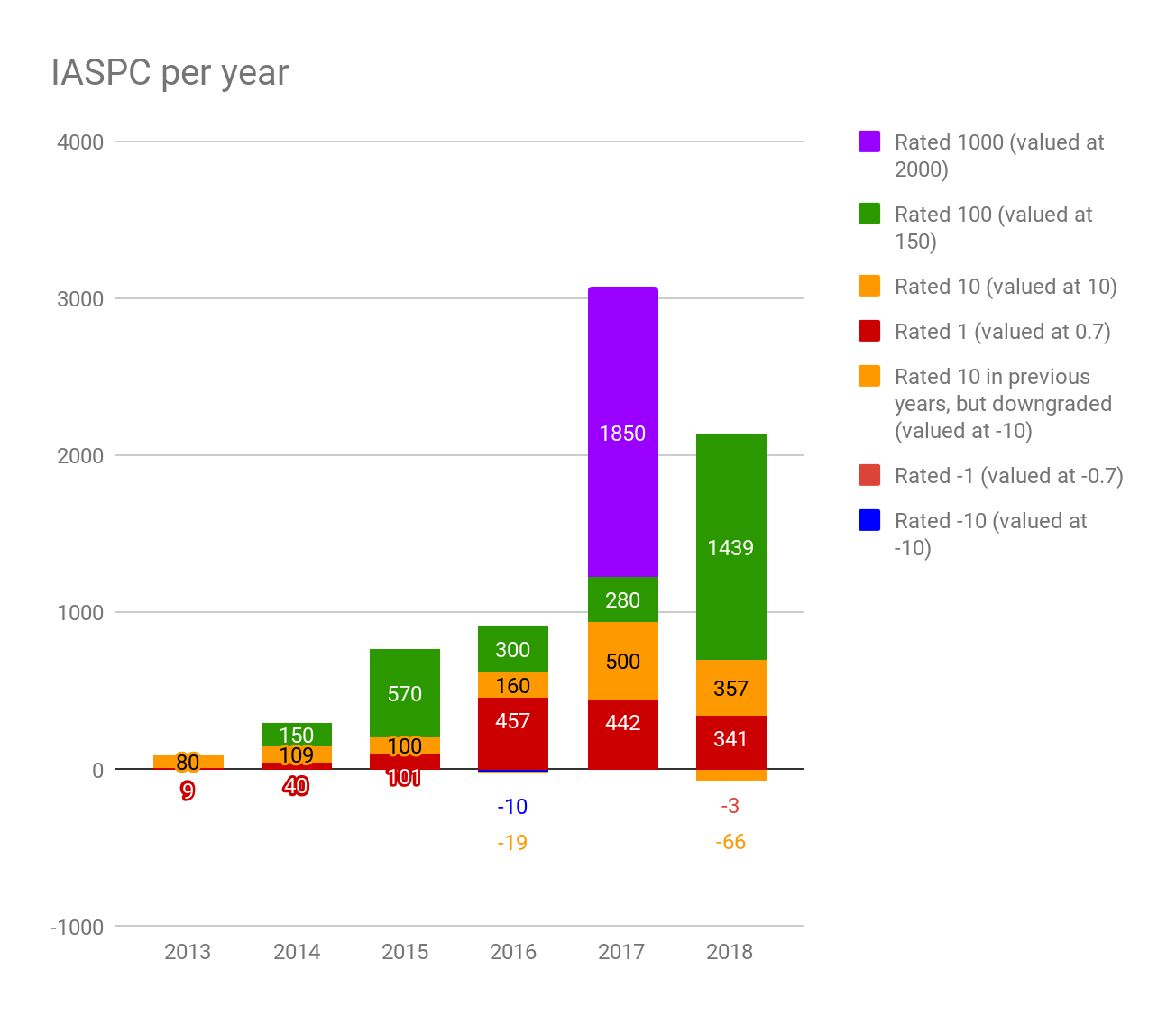

We think the weightings should be more spread out. For instance the rated-100 plan changes are more than 100-times higher-impact than the rated-1 plan changes. We haven’t yet updated our system for rating plan changes, but if we use our current best guess (based on donor dollar estimates of the value of different changes), we get the following chart:

It’s challenging to measure our impact, and there are many details and issues with the system, some of which are explained in the full document. Nevertheless, we think the system serves to give a rough indication of our total impact over time.

You can see a summary of our entire engagement funnel here and in the full document.

Historical cost-effectiveness

Past plan change impact

In 2018, we spent $1.4m and used 7.9 years of labour from the full-time team. This brings our totals over our entire history up to $3.2m and 27 years.

In that time, we’ve tracked about 6000 IASPC, so about 60 rated-100 plan changes or an equivalent number of smaller changes.

This would mean that we have incurred $45,000 and 0.45 core-person-years of costs per 100 IASPC points. So, one way to estimate our cost-effectiveness is to compare the value of a rated-100 plan change to these costs.

It’s challenging to say how cost-effective this makes 80,000 Hours overall, and it involves many difficult judgement calls.

Our own view is that the median rated-100 plan change represents (in expectation) a counterfactually-adjusted year or more of additional labour contributed to a top problem area at a level that’s similarly effective to the labour from staff at 80,000 Hours. Given that it has cost us 0.45 staff years to bring about one such change, and the financial costs seem relatively small, this would make the value of these plans more than double our costs.

We’ve also asked donors and researchers in the community to estimate the value of a several year speed-up into the roles taken by rated-100 plan changes measured in dollars of donations to the EA Long-term Fund, and typically this gives figures of $1m-$3m. However, we’re aware of many criticisms of this approach, including some significant reasons why it could overstate our impact.

Due to these problems, we encourage prospective donors to make their own assessments of our impact compared to our costs. We can provide donors who are considering giving over $100,000 more information on our costs and plan changes. We are also aiming to make some significant improvements to how we evaluate our impact during our next annual review.

Also note there are some important categories of plan change missing from these figures. Perhaps the most important is that the figures above ignore any future impact that will result from our past activities. We expect that even if we dramatically cut back investment in 80,000 Hours, our website and community would continue to produce about 1000 IASPC points per year. If we included this additional impact of our past work, it would substantially increase our impact figures.

Some other categories include: (i) plan changes that happened but we don’t know about (ii) negative plan changes whose impact was reduced by us (we now try to track these, but probably haven’t captured many of them) (iii) people who were put off effective altruism by our work.

Other types of impact

We also think we have had further impact that’s not easily tracked as plan changes, which could be both positive and negative.

For instance, according to the effective altruism survey, 25% of people who first got involved in effective altruism in 2018 said they first found out about it through 80,000 Hours, up from 9% in 2016 and 8% over the whole sample. In our previous review, we mentioned three other surveys showing similar figures, as did our survey of EA leaders.

80,000 Hours was also the most commonly cited factor in what caused people to “get involved” in effective altruism (rather than merely hear about it).

If you think this expansion of the community has been good, then this could be a major additional source of impact. Though if you think the community should grow more slowly or our content is appealing to the wrong audience, this could be negative.

80,000 Hours has also shifted the community in various ways, such as making it more focused on career changes rather than only donations, and more focused on longtermism.

This suggests that another way to value the impact of 80,000 Hours would be to value the effective altruism community as a whole, assign a fraction of that value to 80,000 Hours, and compare it to our costs. Opinions on the financial value of the effective altruism community vary widely, so readers who’d like to evaluate us in this way can do so using their own estimates of its value.

Why didn’t IASPC points grow in 2018?

One problem we face is a lack of growth in the total number of IASPC points we track. This year, we recorded fewer new IASPC points than in 2017, and we missed our growth target of 2200 by 487 points (though we nearly made the target with updated plan change weightings). What happened?

The clearest reason why the growth rate in IASPC went down is that we didn’t record another rated-1000 plan change. If we exclude the rated-1000 plan change, then the number grew 31%. We thought there was only a 25-50% chance of recording a rated-1000 change, so this was not a surprise.

Another important reason is that we did not grow the hours we spent on one-on-one advice as we originally planned. This was because we unexpectedly lost a team member for over six months. This likely cost around 100-300 IASPC in 2018, so explains a significant fraction of the miss. We also spent more time on hiring and online content than planned, which takes more than a year to pay-off.

Another factor is that we recorded 12 fewer rated-10 plan changes in 2018 (-24%) than 2017. There are several potential explanations for this. One is that we think we probably applied a more stringent standard to categorising a plan change rated-10, which we roughly estimated might lead to a 20% underestimate of their number. We will make another round of changes to the process we use to rate plan changes next year to try to avoid this problem.

A more concerning potential explanation would be that the effectiveness of in-person advice has gone down. Our best guess is that we spent somewhere between the same number of hours and 20% fewer hours advising in 2018. So, one possibility is that we invested less time in advising, leading to fewer plan changes. Another possibility is that we spent the same amount of time advising, but the 6-month conversion rate into rated-10 plan changes declined about 24%.

However, this data is very noisy, and the 6-month rate doesn’t tell us much about the long-term conversion rate, or the overall case for the cost-effectiveness of advising. We think there’s a good chance that the long-term conversion rate of 2018 advising will actually be higher, because we focused more on people who might make rated-100 plan changes over the coming years. Nevertheless, we’ll closely monitor this trend next year, and we now track hours spent advising more precisely so we’ll be better able to measure IASPC/hour in the future.

Rated-1 plan changes declined by 145. We think this is mainly because, as they were not a focus, we made less effort to track them.

We give more details on what drove the changes in each category of plan change in the full document.

Next year, we very roughly estimate we’ll track between 600 – 4000 IASPC, compared to 2000 over 2018 (updated weightings). This means there’s a reasonable chance that IASPC points also don’t grow next year. This is mainly because (1) the total is dominated by outliers which makes it volatile (2) the pool of rated-10 plan changes that might upgrade to rated-100 only grew 30% (3) if we increase the capacity of the in-person team, most of the impact won’t arrive until 2020 (and even later for online content) because of the time it takes to hire as well as the lag between advising and the plan changes it creates. See more detail on our projections for next year.

However, if we’re able to hire, then over a three year period we think it’s likely we can grow the annual number of IASPC points tracked by several fold.

There’s strong demand from top candidates for increased advising

Advising (formerly ‘coaching’) capacity was oversubscribed at the start of 2018 so we closed applications, cut back promotion of it on the site, and asked people to sign-up to a waitlist. Over the year, 3,800 people signed up to the waitlist, and as of 1st December 2018, over 1,000 were still waiting.

We estimate that around 10% of these people are ‘tier 1’ applicants,2 who are highly-effective to advise. As mentioned earlier, a typical tier 1 applicant might have studied computer science at a global top 20 university, have read our material about AI safety, and want our help switching into a relevant graduate programme. Another example would be a medical doctor with a long-term focus who wants to switch into biorisk.

We’re confident that if we started to promote the advising, we could double or triple the number of tier 1 applicants. For instance, we have 210,000 people on our newsletter and haven’t promoted it there. If we can continue to grow audience engagement 60% per year, that number will further grow.

With the current team, we predict we can advise 100-400 people next year (compared to 217 this year, depending on how much time we spend hiring). But to meet demand from tier 1 applicants, we’d have to add one or two extra advisors right away, and then grow the number in line with our audience after that.

Advising capacity seems that it will be a key bottleneck to taking full advantage of the increasing size and quality of our audience over the coming years. A large proportion of potential plan changes seem to require some kind of one-on-one contact to make a rated-10+ plan change, so even though we’ve grown our audience, it doesn’t result in large IASPC growth if it’s not matched with more advising (or another in-person programme).

We think specialist advising and headhunting are likely as effective or more effective than the existing advising, and work with a different sub-section of the audience, so are a further avenue for expansion.

Currently, Peter McIntyre spends the majority of his time headhunting, but this is only enough time to thoroughly serve a couple of organisations. We think there are already more organisations that would be worth headhunting for, and this number will continue to grow over the coming years.

A 3-year expansion plan

For these reasons, we think that a top priority over three years should be to increase team capacity. (We cover our priorities over 2019 in the following section.)

We find it very difficult to estimate future advising effectiveness, both because of the general difficulty in making forecasts and because of some flaws in our impact evaluation methods that we plan to fix in the coming year.

That said, we estimate in the full document that an additional advisor or headhunter working for a year, when supplied with tier 1 applicants, will result in tracking several additional large plan changes, which would be an extra 300 – 3000 IASPC points over three years, with a central estimate of 1000 (updated weightings), equivalent to 6-7 rated-100 plan changes.

To provide one year of advising, we would also need to hire someone on the web and research teams to bring in tier 1 applicants, 10% of a staff member working on operations, and 20% of a manager for all of these. This means the total cost of a year of advising is about 2.3 years of labour from the team. We think the expected return of about 1000 IASPC is several times these costs. (At the current margin, we also think the costs are lower because we already have an excess of tier 1 applicants, but in the long term we would need further build the audience.)

We’re unsure how many advisors we’ll be able to fill with tier 1 applicants before we hit diminishing returns, but think it’s plausible we could get to 10 advisors or headhunters in three years. This would mean the total team would need to contain 25 people; including 10 on the research & web teams to bring in more tier 1 applicants (or better), as well as continue to improve our advice, and 5 working on operations and management. We sketch out a path towards this in the full document.

This means that if we’re able to expand on this trajectory without any major setbacks, our aim would be to reach 10,000 IASPC per year within five years, with a rough range of 3,000 – 30,000. We say five years because it takes three years for the advising to fully payoff, and it will take three years to first grow the team. Nevertheless, this is five-fold growth from 2018, and it may be achievable with a cost-effectiveness similar to today.

Our intention is to aim for this growth trajectory, while monitoring how many tier 1 applicants we’re finding and our marginal cost-effectiveness, so that we can change tack if we hit diminishing returns.

10,000 IASPC per year would be about 30 rated-100+ plan changes per year. At that scale, we’d be responsible for a significant fraction of the people working on AI safety, global catastrophic biorisk, global priorities research and effective altruism. It would mean we could contribute to outcomes like building a network of over one hundred people working on AI policy; have our headhunters be a major source of candidates for the DeepMind and OpenAI safety and policy teams; and help quickly staff new effective altruism projects.

See more detail on these expansion plans.

Weaknesses of 80,000 Hours and risks of expansion

In this section, we outline what we currently believe to be our main weaknesses, the main ways our expansion could fail or even be counterproductive, and the main reasons we might fail to be cost-effective from the perspective of donors who share our views of global priorities. We recognise these as risks, but think that, despite them, the expected value of growing 80,000 Hours is high.

(The list is not in order of priority.)

The online content might not appeal to the right people or it might put them off effective altruism

It’s only easy for us to measure people attracted by the content; it’s hard to find out about people who become less keen on these problem areas and the effective altruism community after encountering it.

Some of our external advisors believe some of our content might fail to appeal to our ideal target audience, perhaps because our promotion seems ‘salesy,’ our tone at times seems too credulous, or we don’t hit the right balance between rigour and popularisation. This could mean that expanding now, while still positive, will yield far lower returns than if we first improve tone and expand later.

A more serious concern would be if there are people who might have become involved with the effective altruism community or done valuable work in one of our priority areas but instead were put off by our content,3 and so became less likely to engage with these areas in the future. We expect there are some cases like this, but given the evidence we’ve seen so far, would be surprised if it were high enough to offset much of our positive impact.

Unfortunately, the people who have expressed this concern to us generally haven’t been able to point to specific pieces of content it applies to. Our best guess is that most of the worries concern our older content, such as the career guide, rather than the podcast or recent career reviews like our in-depth article on U.S. AI Policy.

For this reason, next year, it’s a key priority to replace or update prominent old content to be more similar in tone to our newer content.

It might be bad to grow the communities focused on our priority problems

There are ways that increasing the number of people working on an area can harm the area, such as making it harder to coordinate. We outline some of them in our article on accidental harm. 80,000 Hours has helped to grow the number of people working on effective altruism and in our priority areas, and so might have contributed to these problems.

This would be an especially big risk if it turned out that the people we attract into a field have worse judgement than those already in it, perhaps because our audience is younger and less experienced or if our content fails to appeal to the ablest people.

To better track this concern, we’ve started to record negative plan changes, and we try to consider the possibility of these harms when rating plan changes. However, we can’t be sure we’re fully capturing this effect, especially because it’s possible to set back an area even if each individual added seems positive in isolation.

Overall, we’re sceptical these problems are so severe that growing the community, or the fields we promote, is harmful at the margin. We think 80,000 Hours also helps to improve the quality of the effective altruism community, and our advisors and headhunters help somewhat to improve coordination and reduce the chance that people cause accidental harm.

We might not be able to find enough tier 1 applicants

Our maximum audience size might not be large enough to expand the team without running into significant diminishing returns. We’re confident we could advise several times as many tier 1 applicants as we did last year (or an equivalent number of even better applicants), though are not sure about a 10-fold increase.

If we run out of tier 1 applicants, however, we can stop hiring as soon as we notice, so we could minimise how many resources are wasted. That said, our maximum growth potential would be smaller, which would reduce the expected value of investments in growth made today. We also hope to use our online content to mitigate this risk by building our audience and bringing them more up to speed.

A related concern is that most of the impact of our advising could come from a small subset of the tier 1 applicants. If this were true and we were able to successfully identify these applicants in advance, then we would have to reinvestigate whether advising the remainder of our tier 1 applicant pool is cost-effective. If not, it might be a mistake to expand capacity.

It’s hard to measure and attribute the impact of our programmes

This means our programmes could easily be much less cost-effective than we believe. It’s very hard to estimate the counterfactual value of each plan change, especially because many members of the community and programmes are often involved, making it difficult to know which actions were actually necessary. It’s also very hard to estimate our opportunity costs. We’ve recently learned about some additional issues with our current estimates, which we hope to fix over 2019.

We still think the current list of plan changes is convincing enough that taking 80,000 Hours to the next level of scale has high expected value, but there’s a reasonable chance that the value of the plan changes will turn out to be significantly lower than we think. If we are able to find out that is happening, we can cut back hiring, but we will have squandered resources in the meantime.

We could be overestimating the value of different career paths, especially junior roles

There could be mistakes in our advice, leading us to overvalue certain career paths or strategies, which would mean we’re having less impact than we think. All considered, we think our advice represents an improvement on what currently exists, but investigating the ways it might be wrong is one reason we want to continue with our research, rather than only acting on our existing findings.

One particularly concerning way we might be wrong is in how we value junior people compared to senior people entering the areas we focus on. 80,000 Hours has the most appeal to people under 30, but many point out that senior people are often a bigger bottleneck. We agree with this, but still think getting junior roles is valuable enough for us to be cost-effective. If you think senior people are even more valuable than we do, it could significantly reduce our cost-effectiveness compared to our own estimates.

In addition, if it turns out that senior people are more important than we think, we may not be able to switch our focus to them. This is because we’re focused on career choice which is more appealing to junior (and perhaps mid-career) people. This would mean that if you think we’ll want to shift more towards appealing to senior people in the future, then 80,000 Hours may be a less attractive project. We hope that our headhunting product will be useful for filling senior roles, but it’s still an experiment and we don’t yet have enough data to be confident in its effectiveness or the number and type of people it can reach.

There is something higher priority for the team to work on than hiring

Going onto our expansion trajectory over the next three years will mean that the five team leads will need to spend about 20% of their time hiring to each make one hire per year. If there were something else they should do that’s much higher return (e.g. improving the online content or impact evaluation), then they should do that first and delay hiring until later.

We think the question of how fast to hire is very difficult and we’re constantly debating it. Currently we think that five per year is manageable and will help us grow. Much above five per year, and most of our time would be spent hiring and there would be risks to the culture. Much below that seems like a failure to adequately grow our team capacity.

Other weaknesses might prevent us from executing on our plans

Scaling up to 25 staff will require great leadership, management and operations. We might not be capable of running an organisation of that scale. In this case, we should stay smaller until we’re better at running an organisation. We think 80,000 Hours is well-run enough that the best approach is to aim to grow the team, and pause if we run into major problems on the way, rather than not aim to grow at all.

We may also fall prey to the normal reasons that startups fail, such as a key staff member leaving, or team conflict, or a PR crisis. We don’t see any particular reason to expect these problems, but given that 80,000 Hours has only been around for about eight years, our outside view should be that the chance of failing each year is not negligible.

We may not be able to hire sufficiently skilled staff

Much of our work is novel and challenging, and requires rare skills, and this makes it hard to find people we’re confident can do it. At the same time, people who are able to do it often have other highly promising options. This makes it unclear whether we’ll be able to find 25 people who are both skilled enough to do the work and for whom 80,000 Hours is their best option.

Summing up

We think the best reason to delay hiring for expansion is that we should first aim to improve (i) our impact evaluation and research to become more confident in our cost-effectiveness (ii) the tone and content of our online content to make sure we appeal to the right people and deliver the right advice. We intend to prioritise improving these issues over 2019, while expanding at a moderate but not maximised rate.

In addition to the normal reasons that organisations often fail, such as key staff leaving, we think some of the most likely reasons our long-term growth will be capped at a lower level than we hope is that (i) we’ll run out of tier 1 applicants more quickly (ii) we won’t be able to hire skilled enough staff. We think the best approach to these challenges is to try to expand and then adjust plans if we’re not able to. However, if you’re much more pessimistic than us, then the expected value of investments in growth today will be lower.

We list other issues we faced in 2018 in the full document.

Priorities for 2019

We intend to continue our focus on creating and scaling a reproducible process to produce rated-100 plan changes with online content and in-person advice.

In setting these priorities, our aim is to balance expansion in line with the growth trajectory sketched earlier, while also dealing with the most tractable weaknesses and risks flagged above. This means looking for projects that both let us grow over the next year, and put us in a better long-term position.

Based on this, over 2019, we currently expect our priorities will be:

- To continue to improve the online content for a ‘tier 1’ audience in the ways we did this year, such as releasing more podcast episodes, analysing our target audience and working on our key ideas series and site redesign. This builds our audience and brings them up to speed, increasing the number of tier 1 applicants in the future. It also reduces the chance that people are put off, and improves our research into the value of different options. So, it both helps with long-term growth and addresses several of the risks mentioned.

To continue to deliver and improve our in-person advice, aiming to advise 100-400 people, and continue our experiments with specialist advising and headhunting, which we think are likely to be even more cost-effective than regular advising.

To implement a round of updates to our impact evaluation process. We face many challenges in accurately evaluating our impact. During the annual review, we’ve become aware of some clear ways to improve the process, and we’d like to implement some of these next year.

To relocate to London, and develop a productive set up and office there.

We very roughly predict we’ll record 600 – 4000 IASPC over 2019. Our main goal is to clear 1500 (all updated weightings).

If we are able to cover the expansion budget, then, unlike last year, we will also prioritise hiring about five people. Which roles we fill will depend on the candidates we find and how our needs unfold over the year, but some higher-priority roles include:

- A research analyst – We don’t currently have anyone on the team focused on writing articles, since Rob is focused on the podcast. Last year we wrote articles like those on operations management, accidental harm and China specialists. In 2019 we’d like to write more about policy careers because we think they are one of the biggest gaps in the effective altruism community. We think additional research and writing capacity would also help us update our content to be more appealing to the highest potential users. This position would be managed by Rob and mentored by Howie. (Update April: We’ve made an offer to someone in this area who has accepted, but will only start at the end of the year.)

Two advisors – We currently only have two advisors: Michelle and Niel. We’re confident there are enough ‘tier 1’ applicants to fill up an extra advisor, because we already have more than we’re able to advise. If we started to promote the application again, we think we could solicit enough tier 1 applicants to fill a second advisor, and perhaps more. We also think it’s likely everyone in this ‘tier 1’ group is worth speaking to at least once. This position would be managed by Michelle. If we found the right candidate, we could also hire an AI technical specialist advisor. (Update April: We’ve made an offer to someone in this area who has accepted, but will only start toward the end of the year.)

An office manager – We think an office manager, or perhaps some other operations roles, would enable the team to be more productive. We’re currently trialing an office manager and are interested in turning this into a full-time role.

A job board manager – We think the job board is worth continuing to operate and expand, because it already sends 5000 clicks through to top vacancies each month and we’ve tracked placements at Open Phil, DeepMind and The Center for the Governance of AI in jobs discovered via the board. Making this a full-time position would allow us to list more jobs, more effectively promote these jobs to our audience (e.g. dozens of users have requested the ability to get email alerts for jobs that match their interests) and use the board to help identify people that are good candidates for our headhunting efforts. This position would be managed by Peter Hartree. (Update April: we’ve hired someone on a 12-month contract for this role.)

A headhunter – Peter McIntyre is only able to cover a couple of organisations, so we think we could fill up a second headhunter over 2019 with top opportunities. However, this is still a relatively new program and we currently believe that Peter’s time is better spent on product development than on hiring and management. Whether we try to recruit an additional headhunter in 2019 will depend in part on the pace of this work.

We feel fairly confident we can fill these positions with people who are a great fit over 2019 for a couple of reasons: (1) we already have strong candidates interested, some of whom have accepted offers, and it’s early in the year (2) we’ve headhunted for similar roles at other organisations and there are good candidates around (3) we think recent hiring (of Michelle and Howie) has gone better than expectations. We also have five managers in the team, so hiring five people means that each manager only needs to hire one person over the year, which seems manageable. You can also see our current team structure here.

If we focus more on hiring, we’ll make somewhat less progress on content and advising over 2019. For instance, we might only advise 100 people rather than 200. However, hiring will enable us to grow from 2020 onwards with the aim of hitting the five-year growth target mentioned earlier.

More detail on our 2019 priorities and strategy.

Fundraising targets

First target – our current round

Our first target is to cover our 2019 costs if we’re on our expansion trajectory, and end the period with 12 months’ reserves.

This means raising enough to cover the team of 12.6 full-time-equivalent staff we had as of December 2018, honour other existing commitments over this period,4 and hire 5.9 new full-time-equivalent staff (of which we’ve already made offers to 3.4).

To end the period with 12 months’ reserves, we need enough cash on hand in December 2019 to cover our 2020 costs on the expansion trajectory in which we intend to hire another 4.5 full-time-equivalent staff over 2020.

Taking account of cash on hand as of December 2018, and passive income we expect to receive over the period, this requires raising an additional $4.7m. Of this, we have already raised $4.3m, of which most has already been received. This means that to close our first target, we need to raise an additional $400,000.

A large fraction of the funding we have received so far comes from a $4.8m grant from Open Philanthropy split over two years. We have also received grants from BERI, the Effective Altruism Meta Fund, and some individual donors.

Second target – commitments to December 2019 round

Our secondary target is to raise commitments to cover our Dec 2020 round.

We’re keen to raise these commitments for next year because it’s valuable to be able to plan over a two year horizon. In particular, we want to be able to make multi-year commitments to our staff, so they will stick with the organisation and build up expertise, and this is more credible if we already have the committed funds. Many of our other expenses (e.g. office rent) also involve long-term commitments. Financial commitments also allows us to focus our attention on execution rather than fundraising.

If we make the first target, then we will already have enough cash on hand to cover our 2020 costs. However, we would need to raise additional funds to let us end 2020 with 12 months’ reserves. This requires raising enough to cover our expected 2021 budget having made 10.4 hires over 2019-2020. We expect this amount will be about $4.1m, of which we have already raised $2.7m of commitments. This leaves us with a gap of $1.3m.

You can see the calculations behind these figures in the full document.

We think providing funding to expand over the next two years, and especially next year, is highly cost-effective for someone fairly aligned with our approach.

We don’t expect to raise much more than this, but if we did, we could put it towards our Dec 2020 target and fund the remainder of the three year expansion plan covered above. Having even longer commitments is especially valuable for attracting great managers who want to work with the organisation as it scales up.5

How to donate

If you’re interested in covering this year’s funding gap of $400,000, you can donate directly through the Effective Altruism Funds platform. To do this, make an account, then assign your donation to 80,000 Hours. Making an account only takes a minute. If you’re already logged in, you can access our page here.

The platform accepts all major credit & debit cards, monthly direct debits and bank transfers. For donations over $10,000 we can also accept direct bank transfers and donations of assets, including cryptocurrencies.

If we receive more than $400,000 this year, we will put it towards our second target.

If you’re interested in providing a larger donation and have questions, or would like to make commitments to donate in future years, please contact me: direct.ben at 80000hours.org.

If you think our research and advice is useful, and want to support our vision to expand and help solve the biggest skill bottlenecks facing the most pressing problems, we really appreciate your help.

Want to see more detail on what we’ve covered in this review?

Notes and references

- Cullen estimated there’s under a 5% chance they’d be on this path without 80,000 Hours. We think that is likely too low, but even if the number is much higher this is a high-value plan change.↩

- Typically around 20% of applicants are rated ‘tier 1’ but we assume that because it’s much easier to sign up to the waitlist, the conversion rate will be lower. Of waitlist applicants who applied this year, 16% were rated tier-1, though the majority of those invited didn’t apply – likely due to their request no longer being current.↩

- It’s also possible that our content could negatively affect the brand of priority fields or top organisations or that it could poorly frame an important area. We work in areas that are relatively neglected and fragile, which makes it particularly easy to damage their brands in ways that can be hard to reverse. We’ve written about this risk, and how to mitigate it, here.↩

- For instance, maintain the office, expand tech services in line with our scale, and give salary raises in line with our policy.↩

- One risk of giving us funds to cover expenses beyond the next year is that we won’t be able to — or it won’t be prudent to — grow our spending as quickly as the expansion trajectory sketched out. For instance, we may not find enough tier 1 applicants or qualified staff.

If this turns out to be the case, then we will accumulate reserves. We propose a policy that if we would exceed 30 months’ reserves when we fundraise (based on cash on hand), we will not collect all of the funds committed in future years. For instance, if we have $6m of committed funds for Dec 2020, but at that point collecting these funds would mean we have $1.5m more reserves than is required to have 30 months, we will reduce the commitments we collect by 25%. (We implemented something similar in 2017.)↩