Updates to our problem rankings of factory farming, climate change, and more

At 80,000 Hours, we are interested in the question: “if you want to find the best way to have a positive impact with your career, what should you do on the margin?” The ‘on the margin’ qualifier is crucial. We are asking how you can have a bigger impact, given how the rest of society spends its resources.

To help our readers think this through, we publish a list of what we see as the world’s most pressing problems. We rank the top most issues by our assessment of where additional work and resources will have the greatest positive impact, considered impartially and in expectation.

Every problem on our list is there because we think it’s very important and a big opportunity for doing good. We’re excited for our readers to make progress on all of them, and think all of them would ideally get more resources and attention than they currently do from society at large.

The most pressing problems are those that have the greatest combination of being:

- Large in scale: solving the issue improves more lives to a larger extent over the long run.

- Neglected by others: the best interventions aren’t already being done.

- Tractable: we can make progress if we try.

We’ve recently updated our list. Here are the biggest changes:

- We now rank factory farming among the top problems in the world. (See why.)

- We’ve simplified the list into three categories: top most pressing problems, a new category for ‘emerging challenges,’ and other pressing problems (issues we think are underrated by society as a whole but aren’t quite as pressing as our top issues given work already happening). (See more.)

- We now rank climate change in the category of other pressing problems alongside global health, rather than among the most pressing problems in the world. (See why.)

New articles and updates:

- We’ve substantially updated our content on catastrophic misuse risks and AI governance in our AI problem profile.

- We have new articles on:

We are also working on or thinking about publishing new articles on:

- Global health

- Building capacity for top world problems

- Wild animal suffering

- Invertebrate welfare

- Global priorities research

- Other sub-problems relating to transformative AI

We expect to continue updating our list as we learn more and our views evolve. We’re not confident that our ranking of global problems is right or that we’re including everything we should. In fact, we’re confident that we don’t have it right — comparing complex global issues is such a difficult research question that it’d be shocking if we did!

But when we make decisions about how to focus our resources — our time, our money, our careers — we can’t avoid prioritisation. We think there are lots of benefits to being explicit about our choices. And we hope this list gives our audience a jumping off point for deciding which problems they should focus on. Read more in our FAQ on ranking global issues.

You can see our full ranking of pressing global problems here. Click through to the articles to see the arguments for and against each problem being particularly pressing and the best ways we know for you to help.

We explain the biggest changes to the rankings below.

Table of Contents

Factory farming

We have written a new, in-depth problem profile on factory farming. We now rank it among the top problems in the world to work on.

In our problem profile, Benjamin Hilton reports that there are around 1.6-4.5 trillion farmed animals killed every year. The vast majority of these are raised in factory farms. This causes a huge amount of suffering, and we expect these numbers to continue to grow in the coming decades.

As Benjamin explained in his article:

- Around 24 billion chickens are alive in farms at any time. We slaughter around 75 billion each year.

- Around one billion pigs are alive in farms at any one time. We slaughter around 1.5 billion each year.

- Around 1.5 billion cattle are alive in farms at any one time. We slaughter around 300 million per year.

- Around 2.2 billion sheep and goats are alive in farms at any one time. We slaughter around 1.05 billion each year.

- Around 100-180 billion fish are alive in farms at any one time. We kill around 100 billion farmed fish each year. (Many more fish are wild-caught.)

- We kill around 255-605 billion farmed decapod crustaceans for food each year. That includes:

- Crabs (5-16 billion slaughtered each year)

- Crayfish and lobsters (37-60 billion slaughtered each year)

- Shrimp (213-530 billion slaughtered each year)

Many of these animals suffer intensely for much of their lives on farms.

New research from Rethink Priorities suggests that while there’s a lot of uncertainty about the intensity of farmed animals’ experiences, it’s difficult to justify extremely low estimates of their capacities to suffer. Even significantly discounting the moral importance of animals compared to humans, which we think is reasonable, the scale of this suffering and death is still extreme. And we think most plausible moral views would put significant weight on mitigating such outcomes.

We also think it’s moderately tractable to make progress on this problem and that it’s highly neglected compared to many other other issues, with only about $410 million a year currently being spent on it.

It’s hard to know how to compare this kind of problem to other global problems. We try to approach these questions from a standpoint of moral uncertainty, impartiality, and concern for future generations.

In general, because we try to take into account how issues will affect all future individuals, we focus a lot on reducing existential risks. We think society as a whole underrates these risks and that they are hugely important.

But one might also reasonably think that there are very few effective interventions with lasting impacts that we can pursue now, which will predictably influence the long-term future. Additionally, if you have doubts about whether the future will be net positive, this boosts the priority of working on issues that improve the quality of the future or relieve suffering in the present.

Given how tricky the empirical and philosophical questions involved here are, we think these considerations place mitigating factory farming roughly on par with some smaller existential risks, like the risks posed by nuclear weapons. That said, we still consider it less pressing than existential risks where there are plausibly single or even double-digit chances of an existential catastrophe this century — like from AI.

For much more detail, read our new problem profile on factory farming.

Emerging challenges

We’ve added a new category for problems called ’emerging challenges.’ We think of this as a flexible category that allows us to comfortably include content about problems that we have a lot of remaining uncertainties about, but which could be extremely pressing and competitive with our top problems. It contains issues like the moral status of digital minds, space governance, and stable totalitarianism.

These issues don’t yet have well-developed fields built around them like biosecurity and AI safety do. The career paths within them may be less clearly defined, and overall, pursuing work on these problems should be thought of as high-variance.

Most of these issues are incredibly neglected. Some of them, like understanding the moral status of digital minds or invertebrate welfare, have only dozens of people working on them full time and only a few small funding sources. Meanwhile, hundreds, thousands, or even tens of thousands of people work on some of the issues we list on our page, with millions, billions, or even (in the case of climate change) over a trillion dollars in annual funding dedicated to solving them. And several issues we don’t list, like education in wealthy countries, have even more resources devoted to them.

We think this extreme neglectedness makes it particularly high impact to make progress on these emerging challenges — if you can.

This is balanced in part by the fact that it might be very hard to make progress on these issues (how does one increases society’s understanding of the moral status of digital minds?), or they may turn out to be much less pressing after further investigation. Since so little work has been done on them, our understanding of these issues is limited, and it will be harder to find collaborators or other support to work on them.

But even so, and partly because these fields aren’t well defined, we think people who are well-suited to working on them can have a really big impact by getting in on the ground floor. We recommend learning everything there is to learn about the topic (which often isn’t very much due to limited research), and then helping to shape the field and assess the pressingness of the issue with an insider’s perspective.

For example, we think of AI safety as having been in this category about a decade ago — and the people who pioneered the field have been disproportionately impactful in part because they were the only ones working on it.

Tackling these issues is not an easy path. There usually won’t be many organisations or jobs available, meaning you’ll probably have to chart your own course. This can be confusing and challenging, and there is often a much higher chance that it won’t work out, or that you might even do harm by shaping a burgeoning field in a negative way. This means it’s worth being extra careful, and it’s certainly not everyone’s best option to work on an emerging challenge.

But for those who have the right background and aptitudes to thrive in this kind of work, it can be extremely promising.

Climate change

Climate change is a very important issue, and we think, in general, more resources should be going toward addressing it. Humanity’s greenhouse gas emissions have triggered rising global temperatures, which are already impacting people’s lives. Projections suggest this will result in many millions of avoidable deaths and widespread disruption and harm in the coming decades.1 The harms of climate change are arguably particularly objectionable because they will generally most burden the populations who have contributed least to the problem.

We think, however, that given the work that is already happening to mitigate climate change, and considering the scale of other, more neglected issues, many people can do even more good tackling issues like nuclear weapons, catastrophic pandemics, factory farming, and risks from artificial intelligence.

The topline reasons for listing climate change near the top of our ‘other pressing problems’ section, rather than in our ‘most pressing problems’ section, are:

- Climate change is significantly less neglected than other problems we focus on, and we expect that to continue.

- Substantial progress has already been made in addressing climate change, which makes the most extreme global outcomes less likely than they might have been otherwise. We think it’s likely this progress will continue.

- The most recent projections indicate that while the world is likely to miss the goal of keeping global warming below 2°C, it’s less likely than previously thought to exceed 4°C.

- While lower levels of warming can still do a lot of damage, it’s much less likely to pose a risk of human extinction than some other threats, like AI, pandemics, and nuclear war.

Climate change is projected to have serious consequences for the many of the most vulnerable populations, such as people in India who already face the challenges of extreme heat. But climate change is not a unique threat in this regard. Preventable diseases and premature deaths also disproportionately burden people in low-income countries, and we believe much more should be done to address this problem. We think climate change is roughly comparable to the general challenge of improving global health and wellbeing.

We will continue to list climate change roles on our job board, just as we do for roles focused on improving global health.

Below we’ll give more detail on recent research and our thinking about how the neglectedness, scale, and tractability of climate change compares to other problems on our list.

Neglectedness

Climate change is significantly less neglected than it was in the recent past and much less neglected than most of the other issues on our list.

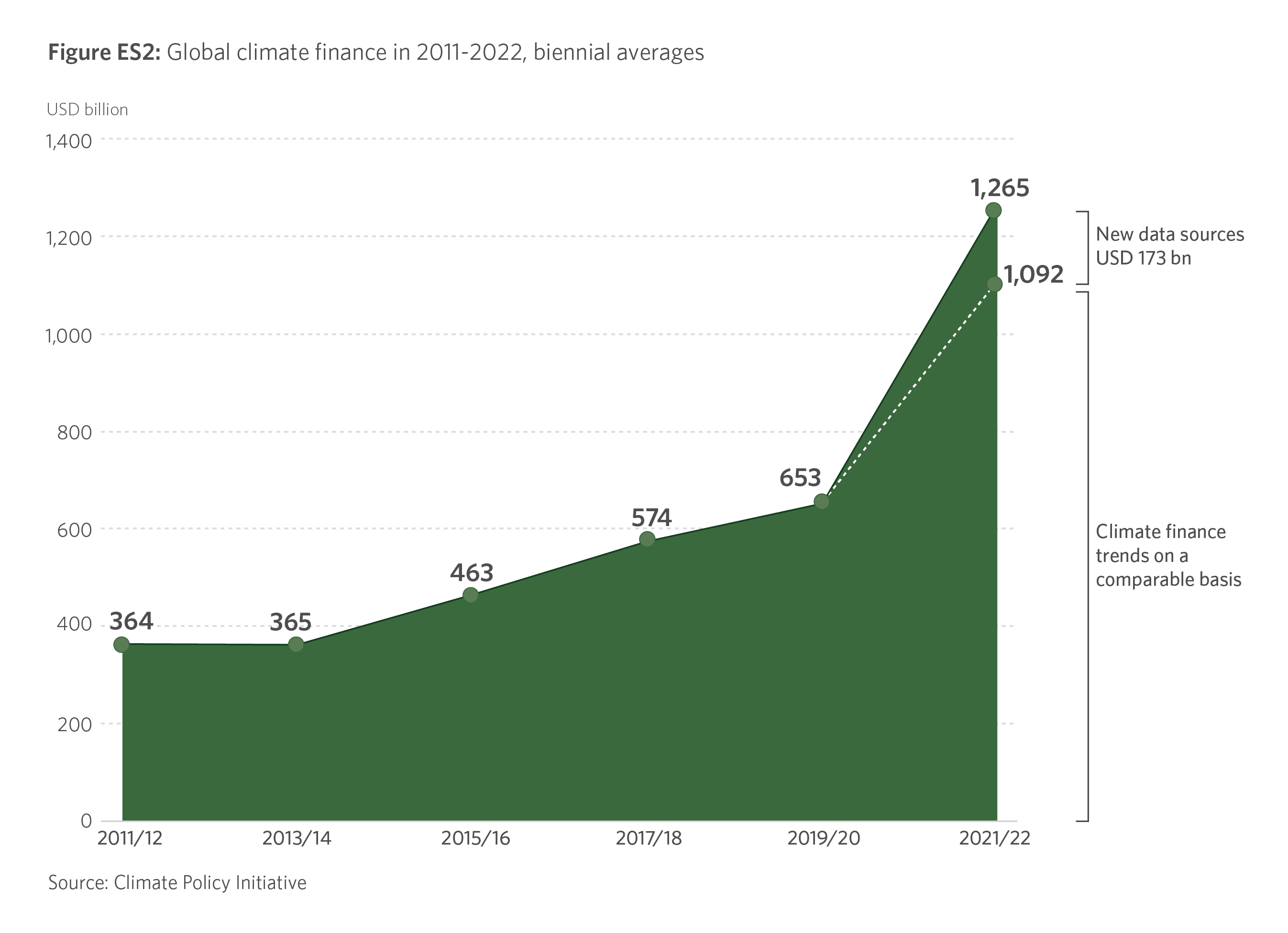

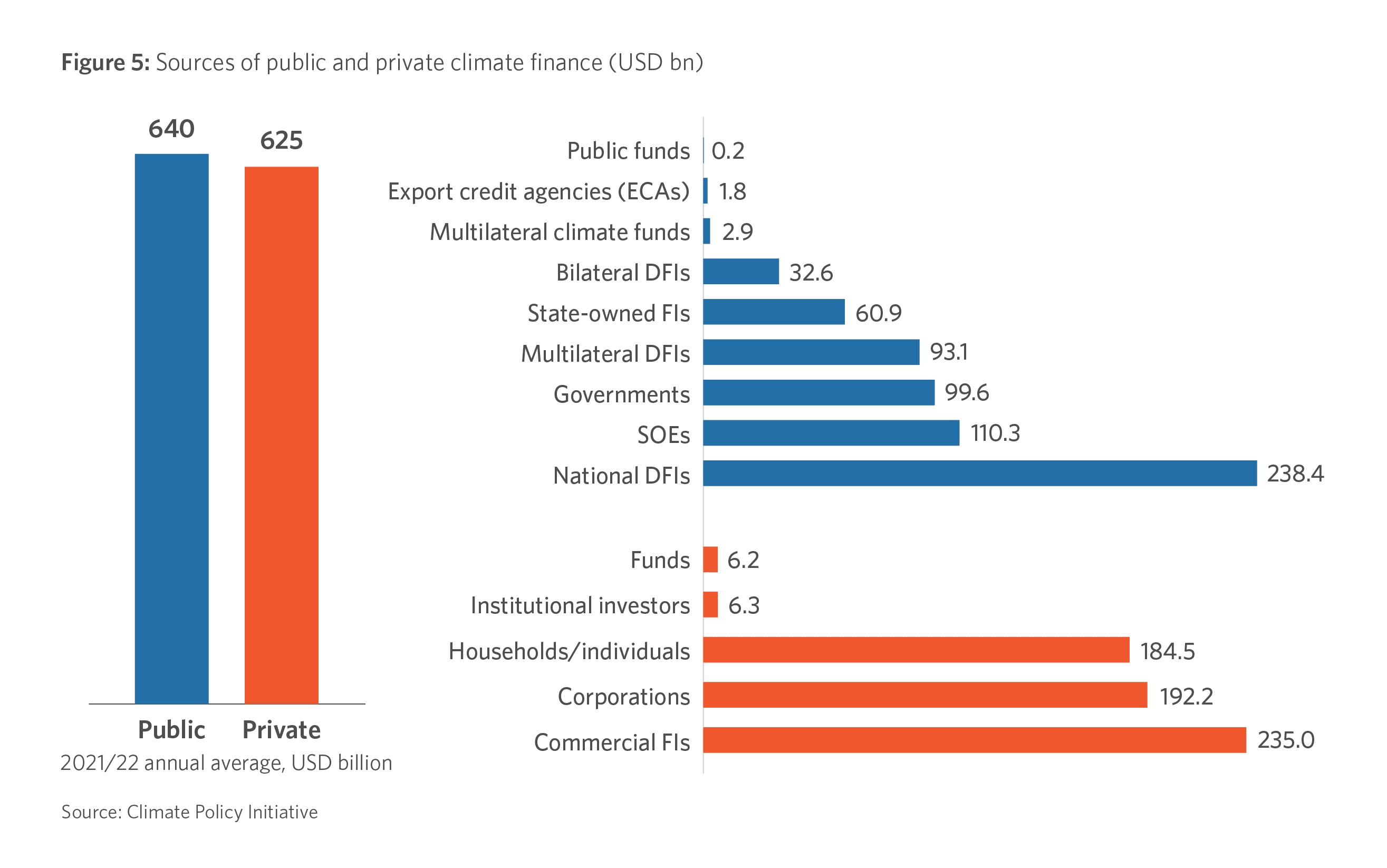

When we published an updated article on climate change in 2022, we cited an estimate from the Climate Policy Initiative that global climate finance was around $640 billion annually in 2019/20. The most recent version of that estimate has nearly doubled to $1.265 trillion.

This is about 10 times the amount of global funding for biosecurity, according to a recent estimate. It’s more than 3,000 times the amount of funding going to factory farming.2

Though we haven’t done nearly enough — and we should have done more much sooner — humanity has broadly recognised climate change as a major world problem and devoted significant resources to addressing it. For this reason, warming looks like it will be significantly less severe than it might have otherwise been.

Again, more climate change funding is still needed — the IPCC has called for 3-6x the current funding level — but the recent increase is a positive development.

And there’s widespread support for continuing action on climate change:

- In opinion polls, climate change is consistently ranked as one of the most important global problems. A 2021 poll found that a plurality of respondents in the EU believed climate change was the most important single problem facing the world, ranking above poverty, infectious disease, and terrorism.

- A 2022 poll of 21,000 people living in 22 countries found that 36% thought that climate change and environmental protection to be among the top three problems facing the world.

- Public support for climate policies is high worldwide. A 2024 survey published in Nature found that 89% of respondents wanted their governments to do more to tackle climate change.

The 2024 study found that people tend to underestimate how supportive others are of tackling climate change. Other studies have shown similar findings. As Hannah Ritchie notes:

A study published in Nature Communications found that 80% to 90% of Americans underestimated public support for climate policies. And not by a small amount: they thought that just 37% to 43% were supporters, despite the actual number being 66% to 80%. In other words, they thought people in favour of climate policies were in the minority. In reality, the opposite was true: more than two-thirds of the country wants to see more action.”

Most discussions on climate change are now about the merits of various solutions and the scale of the problem, not whether it exists or is a problem at all.

The IPCC reported with medium confidence that, “By 2020, laws primarily focussed on reducing GHG emissions existed in 56 countries covering 53% of global emissions.” And: “More than 100 countries have either adopted, announced or are discussing net zero GHG or net zero CO2 emissions commitments, covering more than two-thirds of global GHG emissions.”

The future is uncertain, and it’s possible that investment in fighting climate change could stall or even reverse course. This could be due to a backlash against climate action or other shifts in the global political landscape. For example, if Donald Trump were elected president in November, the US federal government would be less likely to invest in ambitious climate change mitigation, and some progress on this issue may stall.

But even a significant slowdown in funding could leave climate change much better funded than our top-ranked problems, which could also be affected by shifting political winds. And it’s notable that climate funding has consistently increased since 2013/2014 despite many tumultuous political events. We also expect significant private investment in climate solutions to continue.

All this matters because we think neglectedness is a key factor in determining how pressing a problem is — in the sense of how much good you can do by working on it. The more work goes into a problem, the more likely it is to hit diminishing returns because the low-hanging fruit has been taken. In other words, if you’re the 100,000th person working on an issue, you’re likely to have a smaller impact, all else being equal, than if you’re the 100th person. (See more on this above.)

We think there is still a lot of good work to be done on climate change, and we hope to see much more investment in the most impactful solutions. That’s why we list it as a pressing problem. But there are other issues that are also large or even larger in scale, that have insufficient resources going into solving them, and which are not as widely recognised.

Scale

Recent climate change developments

Despite what some sceptics have tried to say over the years, climate change is real, it’s already happening, and it has serious impacts on the planet. For example:

But the resources humanity has invested into counteracting climate change are starting to bear fruit. Due to progress in low-carbon technology and increasingly ambitious climate policy, overall warming is likely to be much lower than feared a decade ago.

From 2000 to 2010, global emissions increased by around 3% per year, and the world was tracking slightly above the highest emissions scenario considered by the IPCC, which implied warming of around 5°C by 2100. However, since then, global emissions have slowed considerably and appear to be reaching more of a plateau, making a 5°C warmer world look increasingly unlikely.

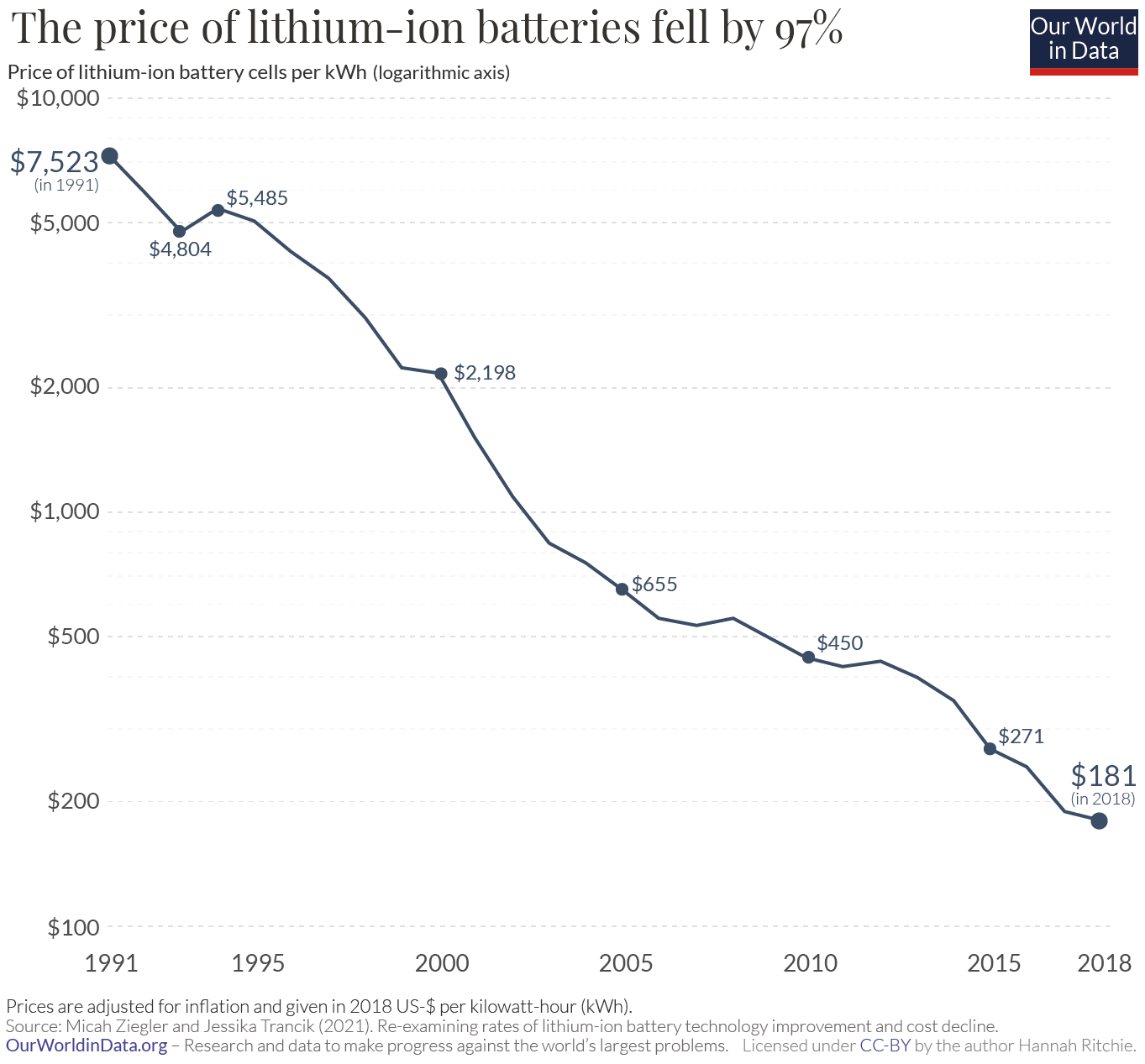

Progress has been driven by strengthening climate policy and the falling costs of low-carbon technologies. Over the last 30 years, the price of lithium-ion batteries has declined by 97%.

This means that batteries will play an increasing role in energy storage, as well as in transport. Some family electric cars now sell for $10,000, and electric cars cost less to maintain and run than petrol cars. In 2020, 4% of new cars sold were electric. That figure increased to 18% only three years later.

A similar trend is happening with solar panel prices, which have declined by more than 500x over the last 50 years.

As a result, the share of global electricity production from solar has increased dramatically in recent years. While still only at 5%, it’s rising fast.3

Even without stringent climate policy, we expect low-carbon technology will play an increasing role in the global energy system.

In addition, climate policies across the world have strengthened in recent years following the 2015 Paris Agreement, which aimed to limit warming to 2°C. As a result, future global temperatures projections have moderated substantially over the last decade. In 2014, current policies suggested a pathway to around 3.9°C of warming in 2100. However, more ambitious climate policy and improved low-carbon technology now place the world on a pathway to warming of around 2.7°C by the end of the century.

If climate policy continues to strengthen in the future, as we hope, warming could be reduced even further. Indeed, if governments stick to their pledges and targets, the most likely level of warming is around 2.1°C.

This is still far more warming than the world should want — 2.1°C would be majorly disruptive, and many of the harms will fall on the world’s most vulnerable people, who contributed least to the problem. But it’s far less warming and less harmful than it might have been had we not begun mitigating it.

This is just experts’ best guess of likely warming based on some key parameters, and there is uncertainty about how emissions will progress over the century and how sensitive the climate is to emissions. But there is broad consensus in the literature that current policies will likely result in warming between 2°C and 3.5°C by 2100 on current policy, with the likelihood of the higher temperatures decreasing over time as policy strengthens. Our children aren’t likely to face a world of 5°C of warming that we once feared.

The IPCC has found that while our uncertainty about the range of future warming had decreased — making higher temperatures less likely — lower temperatures now look somewhat riskier for a range of impacts than previously believed. This somewhat diminishes the positive update from reduced uncertainty about the level of warming, but it appears unlikely to substantially change the general ballpark of the direct harms of climate change, which we turn to next.

Projected deaths

Despite progress, climate change is still on track to cause a huge amount of suffering and millions of deaths over the next century. That’s why we continue to think it makes sense to encourage more people to work towards making further progress.

Several projections have attempted to quantify the potential loss of life due to climate change:

- The World Health Organization has projected 250,000 excess deaths annually between 2030 and 2050.

- A Nature Communications study by R. Daniel Bressler estimated 83 million cumulative excess deaths by 2100 with 4.1°C of warming.4

- In the most extreme scenario under this model, cumulative excess deaths reach nearly 300 million by 2100.

- If warming is limited to 2.4°C by the end of the century, the model projects 9 million excess deaths.

- The Climate Vulnerable Forum has projected 3.4 million deaths per year by 2100 from “unabated climate change”.5

- While not giving precise projections of annual deaths, a 2023 IPPC report found that, “Depending on the level of global warming, the assessed long-term impacts will be up to multiple times higher than currently observed (high confidence) for 127 identified key risks, e.g., in terms of the number of affected people and species.”6

These projections are extremely difficult, so we shouldn’t place too much confidence in any particular estimate. But the scale of these projected effects is consistently disturbing and roughly on a par with the broad range of major world health challenges (largely reflecting global inequalities) like tuberculosis, diarrheal diseases, malaria, outdoor air quality, and HIV/AIDS, which cause many millions of deaths each year.7

While climate change is expected to increase the number of global deaths than there would otherwise have been, the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation recently forecast in its Global Burden of Disease study that between 2022 and 2050, global life expectancy will increase by 4.6 years. This projection factors in the impact of rising temperatures and notes:

Our findings indicate that increases in life expectancy will be largest in countries where it is currently lower, and inequalities between countries will shrink.

Addressing climate change may synergise with other global health initiatives. For example, transitioning to green energy can mitigate climate change while also reducing air pollution, and eradicating diseases like malaria could make societies more resilient to climate-related challenges. Indeed, the Gates Foundation has said, “Malaria eradication may be one of the most cost-effective climate adaptations we can make.”

All things considered, while climate change is a large-scale problem, it seems less severe than threats that pose much more significant risks of human extinction, like we think nuclear war and engineered pandemics do.

See more details in a footnote.8 For a related perspective, see David Wallace-Wells’ New York Times op-ed, “Just How Many People Will Die From Climate Change?”

Economic models

While ‘projected deaths’ are a useful proxy for understanding the impact of climate change and comparing its scale to other problems, it’s highly imperfect and doesn’t capture the full effects of warming. It’s helpful to look at other methods of assessing climate change’s impact to see if they suggest its scale may be more comparable to potentially extinction-level events, like the worst catastrophic pandemics.

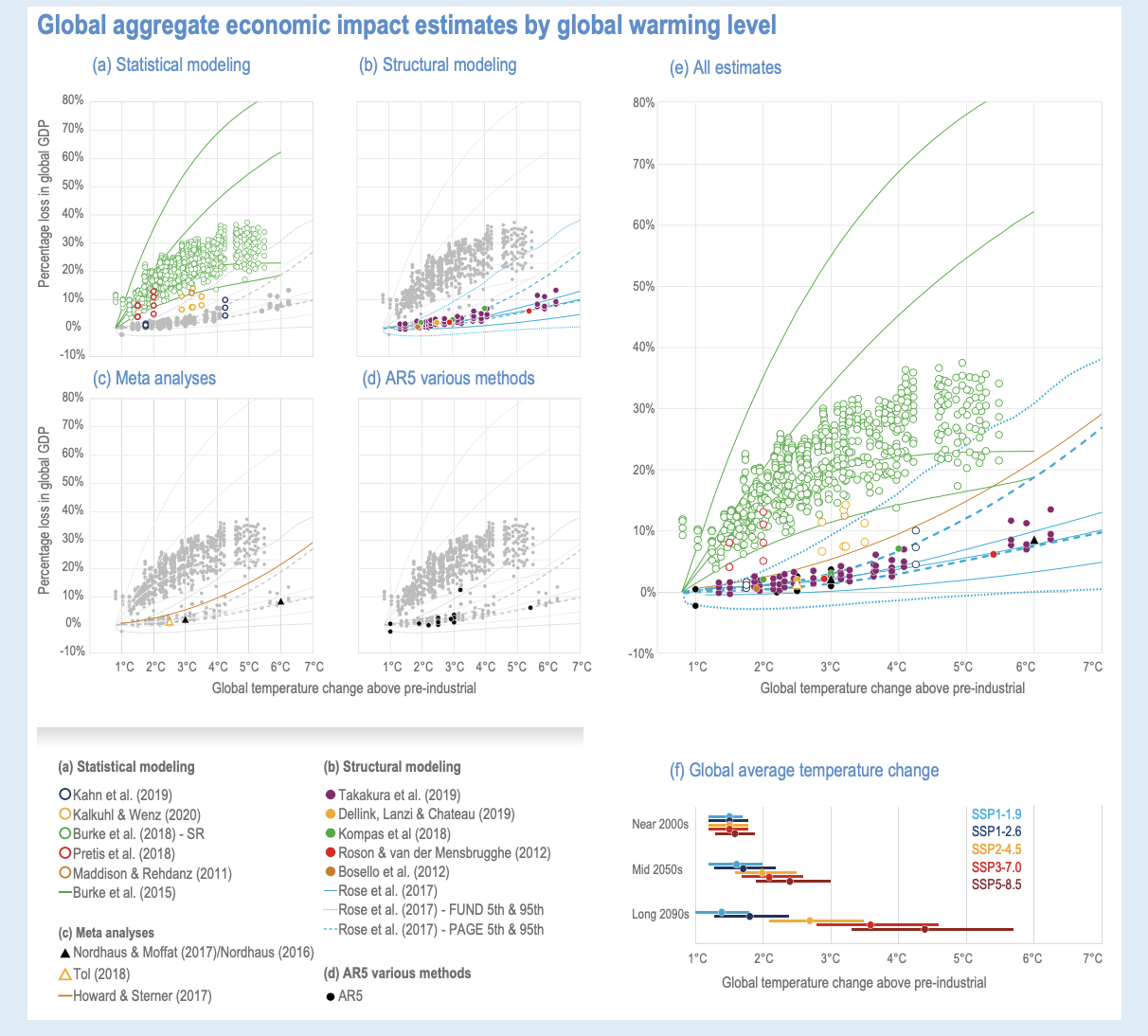

In some ways, climate-economy models provide a broader picture of the impact, because they incorporate negative effects on people’s lives beyond disease and death. Experts in this area project the social impact of warming based on two different kinds of methods:

- Bottom-up models estimate that 2°C to 3.5°C warming by 2100 could reduce global GDP by 1-10% compared to a world without climate change.

- Top-down models suggest more pessimistic outcomes, with potential GDP reductions of around 20%.

Making these projections is exceedingly difficult, so again, we shouldn’t be overly confident in any particular model. It’s also important to note that the costs in these models are relative to a counterfactual future world without climate change, not today’s economy. (See more detail in this footnote.9) Even with climate change, average living standards are expected to rise significantly in the future due to ongoing economic growth.10

For an alternative take arguing that the worst-case effects of climate change remain underrated, even by the IPCC, we recommend “Climate endgame: Exploring catastrophic climate change scenarios” by Kemp et al.

Contributions to existential risk

We’ve argued that even if climate change turns out to be significantly worse than existing projections suggest, it is very unlikely to directly cause human extinction:

- The IPCC and climate models account for various feedback loops and tipping points. The chance of runaway warming to uninhabitable global conditions is considered extremely low.

- Humanity has shown the ability to adapt to climate changes in the past. With decades or centuries of warming, further adaptation is possible, even in extreme scenarios.

We think the direct extinction risk from climate change is less than 1 in 1,000,000. This is comparable to Toby Ord’s estimate of the risk of an existential catastrophe from an asteroid collision in the next century.

We also discuss the possibility of climate change indirectly increasing other catastrophic risks in our problem profile on climate change. Climate change-induced disasters or crises could, for example, fuel international conflict, perhaps increasing the risk of a great power war.11

While we think these indirect risks are real, we don’t think they significantly strengthen the case for working on climate change over other pressing global issues, all things considered.

One reason is that instead of working on climate change, you might instead work on reducing the risk of a great power war directly — for example, by working to reduce the risk of an accidental nuclear launch or fostering cooperation between great powers. It’s possible that working to reduce climate change is in fact more effective on the current margin at reducing the risk of great power war than either of those methods or any others. But our view is that tackling threats as directly as possible is usually a good heuristic, especially when the indirect method already receives a fair amount of resources, as is the case with climate change, as discussed above.

There are also indirect benefits from working on many problems, not just climate change. For example, reducing the risk of great power conflict could plausibly increase the chance that we effectively tackle climate change, because avoiding conflict makes it easier for countries to coordinate with one another to bring down carbon emissions. Similarly, mitigating factory farming could reduce the risk of pandemics, because factory farms increase the risks that a potential pandemic pathogen crosses over from animals to humans.

Tractability

While the neglectedness and scale of climate change tend to count in favour of prioritising it less than our top problems, it is plausibly more tractable than at least some of the other problems. This is a reason to prioritise it more on the margin, since it means that working on it in your career can make a bigger positive difference to solving it.

There are two main reasons to think that climate change is more tractable than other global catastrophic risks. These arguments are discussed in this article by Giving What We Can:

First, there is a clear success metric for climate change: we know we are winning if we reduce carbon emissions. Compared to other problems like AI safety and nuclear security, it is much clearer whether we are making progress on climate change.

Second, because success is relatively easy to measure, it is easier to identify the most promising ways forward. There are now several climate success stories which suggest that progress on climate change is possible if efforts are carefully designed. For example:

- In the 1970s and 1980s, several countries decarbonised their electricity systems by rapid build-out of nuclear power.

- In the 2000s, the German government provided massive subsidies for solar power. This generous policy support made it the world’s largest solar market, and helped to reduce the cost of solar modules by 92% between 2000 and 2020.

- Since 2007, per-person emissions have fallen by a third in the UK, thanks to advances in energy efficiency and replacing coal with gas, then renewables.

- Similar success stories could be told for California and electric cars, and Denmark and wind power.

Because climate change has such a clear success metric and different solutions are now so well-tested, it is one of the more tractable major global risks.

Despite the fact that climate change seems a more tractable problem, we think this does not outweigh the differences in neglectedness and scale between climate change and problems on the top of our list.

There’s still much more to do

There has been substantial progress on climate change, and the risks are now lower than they once were. We might have learned that it was getting worse and the most extreme possibilities were looking more likely, but that hasn’t happened. That doesn’t mean that climate change is no longer a big problem. Under current policies, there is a non-negligible chance of 4°C warming, which would clearly be damaging to the world, and work still needs to be done to reduce emissions more. Even if climate change is less severe than that, many people will likely suffer as a result.

As we discussed at the start of this post and on our problem profiles page, we try to think about the difference we and our readers can make on the margin. We think about what they can do to help as much as they can, given how the rest of society spends resources. We are not saying that all resources directed to climate should instead go to AI and pandemics. In fact, we think that climate change should receive more resources than it does today, just as we think global health should. Our point is that, especially for many people starting their careers, you can probably do even more good by working on other problem areas.

We’re also not telling people currently working on climate change that they should change careers or suggesting their work isn’t valuable. It’s often very valuable, and personal career decisions must weigh many different factors. While the pressingness of the problem you work on is an important and underrated factor in our opinion, considerations like personal fit — and what you enjoy — are also relevant.

Some people argue that climate change should be prioritised in part because the harms it causes are particularly unjust. Many countries that will be most harmed have historically contributed least to greenhouse gas emissions. We don’t explicitly include these kinds of considerations in our rankings, instead focusing on total welfare impacts, but they may motivate many people in their work. Though note that considerations of justice may be relevant to other problems as well — e.g. factory farming or the threat of nuclear war.

Johannes Ackva, a grantmaker who works on climate change, told 80,000 Hours in an interview that early-career people might be advised not to work on the issue because much of the policy, technology, and emissions trajectories could be essentially “locked in” within the next 10-15 years or so. Since you’re most likely to be impactful after at least a decade in your field, a young person pursuing this path may find the most valuable years of their career don’t coincide with the best opportunities to mitigate the harms of climate change.

If you want to work on mitigating climate change, we list climate change roles on our job board and have guidance for what seem to be the best ways to help in our article on the problem. And if you want to donate to organisations that work on this topic, we’d recommend the Founders Pledge Climate Change Fund.

What if I disagree with 80,000 Hours about all of this?

We expect a lot of disagreement with these decisions. One reason you might disagree with our ranking of climate change is if you think it’s more likely to cause human extinction than we’ve argued is plausible, or if you think the risks from advanced AI, catastrophic pandemics, and nuclear weapons are significantly lower than we do.

Figuring out how to compare the impact of working on different problem areas is hard, and there will always be reasonable disagreement about how to do it. Members of our team disagree with one another on these topics all the time.

We also acknowledge that we may well be wrong about these new changes, but that’s also true for every other choice we make as an organisation.

We’re excited for people to engage with our ideas, propose counter-arguments, and develop their own views. We have an article that can help you compare problems for yourself if you’re interested in exploring this further. Many people in our audience and in the effective altruism community have differing views on what issues are most pressing – you can see some argument about these topics on the Effective Altruism Forum.

Much of our other content, such as our career guide, is also designed to be helpful regardless of your problem prioritisation. We think we can still be useful to people even if they totally disagree with us on what issues are most pressing.

Learn more

Factory farming

- Bob Fischer on comparing the welfare of humans, chickens, pigs, octopuses, bees, and more

- Meghan Barrett on challenging our assumptions about insects

- Seren Kell on the research gaps holding back alternative proteins from mass adoption

- Leah Garcés on turning adversaries into allies to change the chicken industry

- Lewis Bollard on the 7 most promising ways to end factory farming, and whether AI is going to be good or bad for animals

- Sharon Nuñez and Jose Valle on going undercover to expose animal cruelty, get rabbit cages banned, and reduce meat consumption

- Andrés Jiménez Zorrilla on the Shrimp Welfare Project

Problem choice

- Want to do good? Here’s how to choose an area to focus on from our career guide

- A framework for comparing global problems in terms of expected impact

- What are the most pressing world problems?

- Frequently asked questions about our pressing problems rankings

- On our research process and principles

- Our full ranking of pressing global problems

Climate change

- Our full problem profile on climate change

- Hannah Ritchie on why it makes sense to be optimistic about the environment

- Johannes Ackva on unfashionable climate interventions that work, and fashionable ones that don’t

- Our climate change debates are out of date and A bunch of handy charts about climate change by Noah Smith

- The world has become more resilient to disasters, but investment is needed to save more lives

- How many people die from extreme temperatures, and how this could change in the future

- Just How Many People Will Die From Climate Change? by David Wallace-Wells

- Climate Change & Longtermism: book-length report

- Why the recent ‘acceleration’ in global warming is what scientists expect

- Explore Our World in Data’s climate change information

Notes and references

- As the IPCC reports:

Human activities, principally through emissions of greenhouse gases, have unequivocally caused global warming, with global surface temperature reaching 1.1°C above 1850-1900 in 2011-2020. Global greenhouse gas emissions have continued to increase, with unequal historical and ongoing contributions arising from unsustainable energy use, land use and land-use change, lifestyles and patterns of consumption and production across regions, between and within countries, and among individuals (high confidence).

…

Widespread and rapid changes in the atmosphere, ocean, cryosphere and biosphere have occurred. Human-caused climate change is already affecting many weather and climate extremes in every region across the globe. This has led to widespread adverse impacts and related losses and damages to nature and people (high confidence). Vulnerable communities who have historically contributed the least to current climate change are disproportionately affected (high confidence).↩

- This estimate has been updated to fix an error in the initial calculation.↩

- Note that this is global electricity, not global energy. Electricity accounted for around 40% of global CO2<.sub> emissions from fossil fuel and industry in 2018.↩

- A New York Times report on this study noted:

Mr. Bressler acknowledged that there were areas of uncertainty in the paper, including those built into some public health research investigating excess deaths caused by heat. He also relied solely on heat-related deaths without adding other climate-related causes of death, including floods, crop failures and civil unrest. The result is that the actual number of deaths could be smaller, or greater. “Based on the current literature,” he said, “this is the best estimate.”↩

- Another paper projected one billion excess deaths by 2100. However, the quantitative methods appeared ad hoc and hard to justify, and such conclusions are not widely accepted.↩

- You might wonder whether we should care about mitigating climate change on behalf of animals. We do care about wild animal welfare, as we care about factory farming.

But our understanding of the field of wild animal welfare is that it’s exceptionally complex, and predicting all the consequences of interventions on behalf of wild animals is very hard. The most in-depth analysis we’ve seen on the question of how climate change affects wild animal welfare (though we’d be interested to see more) is from Brian Tomasik, who favours climate change mitigation but concluded:On balance, I’m extremely uncertain about the net impact of climate change on wild-animal suffering; my probabilities are basically 50% net good vs. 50% net bad when just considering animal suffering on Earth in the next few centuries (ignoring side effects on humanity’s very long-term future).

Though we’re unsure, we think if your primary motivation is animal welfare, there’s a clearer case for working on factory farming, or perhaps doing exploratory research into wild animal welfare, than there is for working on climate change.

Some people care about the environment more broadly, beyond its impact on animal or human wellbeing. If these kinds of considerations are highly important to you, they might justify prioritising climate change more than we do.↩

- See, for instance:

- Tuberculosis killed about 1.28 million people in 2022.

- Diarrheal diseases killed 1.17 million people globally in 2021, including 340,000 children under age five.

- Malaria killed more than 600,000 people in 2020.

- HIV/AIDS killed more than 700,000 people in 2021.

- An estimate 4.72 million died from outdoor air pollution in 2021.↩

- Other Impacts

Climate change is likely to have various other impacts on human life, including mass migration, increased frequency and severity of natural disasters, and changes in temperature-related deaths (with complex regional variations).

However, it’s worth noting that deaths from natural disasters have declined significantly over the last century, despite about 1.3°C of warming.This decline is likely due to the world becoming richer and better able to prepare for and mitigate the harms of natural disasters. While the trend seen here could reverse at some point, we expect as the world continues getting richer, we will be better able to protect ourselves from some of the effects of climate change. (Note that the datasets here are incomplete and patchy, but we expect the most significant omissions to be in the past rather than in more recent decades. This suggests that if we had better data, the decline in disaster-related deaths would look even more stark than it does here.)

There’s also a complicated issue about how climate change will affect deaths from extreme temperatures. Our World in Data has a detailed discussion of this topic, but the key point is that several million people die annually from suboptimal temperatures, with cold-related deaths currently outnumbering heat-related ones by about nine to one globally. The warming we’ve experienced so far has actually decreased deaths on net by reducing more cold-related deaths than it has increased heat-related deaths.

Climate change is likely to reduce extreme temperature deaths in many wealthy countries but increase them in poorer countries. The future impacts on temperature-related deaths are uncertain and depend on the degree of warming and societies’ ability to adapt, but the burden is expected to fall disproportionately on poorer countries.Deaths from conflict are often cited as a major contributor to the scale of climate change’s harm. This is indeed a serious risk and one that needs to be mitigated as we cope with a warming world. In recent history, though, deaths from disease typically far surpass deaths from conflict and war. We expect this to continue to be the case.

One way we might deviate from this trend would be if we experienced a catastrophic great power war, which we’ve written about in a separate article and which we rank among the most pressing problems.

- Bottom-up models use the scientific literature to estimate the costs of different climate impacts, including sea level rise, floods, agriculture, labour productivity, heat stress, and mortality. Top-down models use data on the economic effects of past variations in weather to estimate the future economic costs of warming.

The IPCC chart below shows the results of top-down models in pane (a), and of bottom-up models in pane (b).

Source: IPCC, Impacts, Sixth Assessment Report, Ch 16, Figure Cross-Working Group Box ECONOMIC.1

While there is broad agreement among bottom-up models on the expected costs of 2°C to 3.5°C, the findings of the top-down models are highly sensitive to the statistical methods used. One reanalysis of a prominent top-down model found enormous model uncertainty in top-down models, with a 95% confidence interval of an 84% loss in GDP to a 359% gain.

If the prominent top-down model, Burke et al. (2015), (shown in green in the chart above) had used the controls used in another prominent top-down model, Dell et al. (2012), then Burke et al. (2015) would have found a modest gain from climate change, rather than a dramatic loss.

This calls into question the reliability of top-down models.

Whichever climate-economy models you think are plausible, it is important to note that these estimated costs are relative to a counterfactual world without climate change, not relative to today. Over the course of the 20th Century, global GDP per person increased by 440%. The IPCC sets out five socioeconomic scenarios, which it calls Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs). In the lowest scenario, GDP per capita doubles, whereas in the highest scenario it increases by 1,400%.

Even using the most pessimistic estimates of the costs of 2°C to 3.5°C, income per person is likely to decline by 2–20%, but this will happen in the context of economic growth causing income per person to rise by several hundred percent. In short, even with climate change, average living standards are likely to be much higher in the future.

But despite average living standards rising, many of the poorest people will be hit the hardest. It’s unfortunately the case that this is true for many global problems — catastrophic pandemics and nuclear winter are especially dire for populations that are already vulnerable. (The outcomes of AI-related catastrophes are harder to anticipate, though if it results in human extinction, that obviously affects everyone.)

The finding that average living standards will rise is reflected in the scientific literature on specific impacts. For example, although climate change could, on net, negatively impact agriculture, van Dijk (2021) projected that calories per person will increase by 2050 compared to today.↩

- One response to these arguments would be that model uncertainty should make us more concerned about climate change. It’s possible our understanding of climate change is significantly flawed in some way, and this means we should be more worried. Of course, we should be uncertain in both directions — climate change may end up being far less serious than we think. But the costs of underrating the severity of climate change are possibly higher than overrating it because the scenarios in the extreme tail are catastrophic, maybe even existential.

While this is true, it also applies to the other risks we care about. It’s possible that AI risks and the risk of a catastrophic pandemic could be higher than we think. It’s not clear model uncertainty should be particularly high for climate change — indeed it might be lower. Modelling the climate is plausibly more concrete than modelling something like the risk of an AI-related catastrophe, and much more effort has been invested in this work. While this might make climate change a more appealing cause to work on for various reasons, it reduces the chances that it will be much worse than currently anticipated.↩

- Deaths from conflict are often cited as a major contributor to the scale of climate change’s harm. This is indeed a serious risk and one that needs to be mitigated as we cope with a warming world. In recent history, though, deaths from disease typically far surpass deaths from conflict and war. We expect this to continue to be the case.

One way we might deviate from this trend would be if we experienced a catastrophic great power war, which we’ve written about in a separate article and which we rank among the most pressing problems.