What the hell happened with AGI timelines in 2025?

On this page:

- Introduction

- 1 Articles, books, and other media discussed in the show

- 2 Transcript

- 2.1 Making sense of the timelines madness in 2025 [00:00:00]

- 2.2 The great timelines contraction [00:00:46]

- 2.3 Why timelines went back out again [00:02:10]

- 2.4 Other longstanding reasons AGI could take a good while [00:11:13]

- 2.5 So what's the upshot of all of these updates? [00:14:47]

- 2.6 5 reasons the radical pessimists are still wrong [00:16:54]

- 2.7 Even long timelines are short [00:23:54]

- 3 Learn more

- 4 Related episodes

In early 2025, after OpenAI put out the first-ever reasoning models — o1 and o3 — short timelines to transformative artificial general intelligence swept the AI world. But then, in the second half of 2025, sentiment swung all the way back in the other direction, with people’s forecasts for when AI might really shake up the world blowing out even further than they had been before reasoning models came along.

What the hell happened? Was it just swings in vibes and mood? Confusion? A series of fundamentally unexpected and unpredictable research results?

Host Rob Wiblin has been trying to make sense of it for himself, and here’s the best explanation he’s come up with so far.

This episode was recorded on January 29, 2026.

Video and audio editing: Dominic Armstrong, Milo McGuire, Luke Monsour, and Simon Monsour

Music: CORBIT

Camera operator: Dominic Armstrong

Coordination, transcripts, and web: Katy Moore

Articles, books, and other media discussed in the show

Toby Ord’s analyses:

- The extreme inefficiency of RL for frontier models

- Evidence that recent AI gains are mostly from inference-scaling

- How well does RL scale?

- Are the costs of AI agents also rising exponentially?

- The scaling series on the EA Forum

- See all Toby’s writing on his website

Epoch AI data:

- AI capabilities progress has sped up

- Epoch Capabilities Index

- How well did forecasters predict 2025 AI progress?

- METR Time Horizons

- Can AI companies become profitable?

Other predictions and analyses:

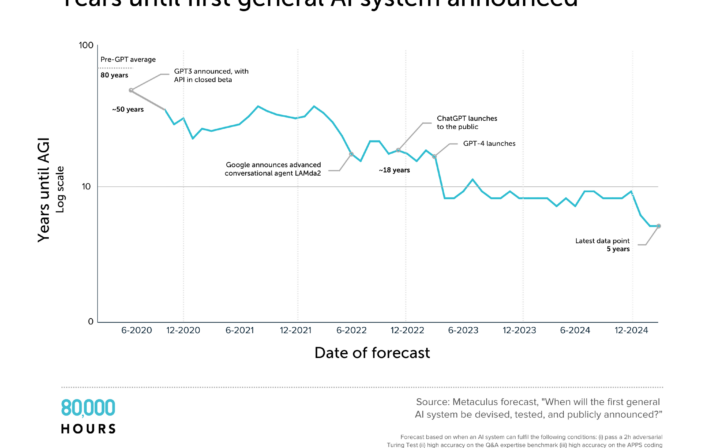

- Metaculus forecast: When will the first general AI system be devised, tested, and publicly announced?

- AI 2027 Model: Dec 2025 Update

- The case for AGI by 2030 by Benjamin Todd

- Timelines forecast used by AI 2027 authors now

- Leading AI expert delays timeline for its possible destruction of humanity — The Guardian coverage

- What’s up with Anthropic predicting AGI by early 2027? by Ryan Greenblatt

- Is 90% of code at Anthropic being written by AIs? by Ryan Greenblatt

- My AGI timeline updates from GPT-5 (and 2025 so far) by Ryan Greenblatt

- Thoughts on AI progress (Dec 2025) by Dwarkesh Patel

- AGI is still 30 years away — Ege Erdil & Tamay Besiroglu — appearance on the Dwarkesh Podcast

The “continual learning” challenge:

- Why I don’t think AGI is right around the corner by Dwarkesh Patel — also reviewed by Zvi Mowshowitz: Dwarkesh Patel on continual learning

- Richard Sutton – Father of RL thinks LLMs are a dead end — appearance on the Dwarkesh Podcast

- Discussion on The Cognitive Revolution podcast with Nathan Labenz

Transcript

Table of Contents

- 1 Making sense of the timelines madness in 2025 [00:00:00]

- 2 The great timelines contraction [00:00:46]

- 3 Why timelines went back out again [00:02:10]

- 4 Other longstanding reasons AGI could take a good while [00:11:13]

- 5 So what’s the upshot of all of these updates? [00:14:47]

- 6 5 reasons the radical pessimists are still wrong [00:16:54]

- 7 Even long timelines are short [00:23:54]

Making sense of the timelines madness in 2025 [00:00:00]

Rob Wiblin: Let’s talk timelines to artificial general intelligence.

In late 2024 and early 2025, after OpenAI put out the first ever set of reasoning models — that is, o1 and o3 — short timelines to transformative artificial general intelligence swept the AI world. But then, in the second half of 2025, a strange thing happened: sentiment swung all the way back in the other direction, with people’s forecasts for when AI might really shake things up blowing out further than they had been even before reasoning models came along in the first place.

What the hell happened? Was it just swings in vibes and mood? Confusion? Just a series of fundamentally unexpected research results?

I’ve been trying to make sense of it myself, and here is the best explanation I’ve come up with.

The great timelines contraction [00:00:46]

Rob Wiblin: The reasoning models like o1 and o3 seemed to have a big impact inside the AI companies as well as in the public outside of them. Sam Altman declared in January last year, “We are now confident we know how to build AGI.” Demis over at DeepMind, who’s normally more circumspect, said he thought AGI was probably three to five years away. And as often the case, Dario from Anthropic had the most colourful turn of phrase: he announced a “country of geniuses in a data centre,” we’re quite likely to get that in the next two to three years.

We also saw huge levels of popular coverage of the AGI scenario known as AI 2027, in which AI research and development is fully automated in 2027 and that then leads in the story to a powerful recursive self improvement loop and a so-called “intelligence explosion.” I think the massive coverage and engagement with that story definitely shifted the vibes as well. Even 80,000 Hours, where I work, made a video about the AI 2027 story that got a stupid number of views. I’m not going to say exactly how many, because I’m sure it will have gone up a whole bunch by the time we post this.

To an extent, all of this hype ran a touch ahead of what people actually believed. When they put out the AI 2027 scenario, the writers, who are absolutely as bullish about AI as you can reasonably get, they still thought that we wouldn’t get a superhuman coder in reality until a year and a half after what actually happens in their story.

But people really did get a lot more excited, and then changed their minds back again. So let’s take a tour of some of the technical factors that drove that.

Why timelines went back out again [00:02:10]

Rob Wiblin: I think it’s no mystery why lots of people, absolutely including me, got super excited about reasoning models when they arrived. When they landed, it just felt like they could suddenly do so many things that the previous generation of AI failed horribly at.

But what made the shine wear off as time went on? Well, the hope among people inside the industry and among AI enthusiasts had been that reinforcement learning on domains that are easily checkable, things like mathematics and coding, that that would generalise to other, messier domains where it’s a lot harder to check if someone has actually done the right thing or gotten the right answer.

People were kind of primed to expect that this might work, because fine-tuning models to follow instructions and be helpful to users really had generalised shockingly well across almost all the different things that users tend to ask AI models for.

But as 2025 wore on, it became apparent that the same thing wasn’t really happening here with reasoning generalisation. The reasoning models that had been optimised to reason were a lot better at math and logic and coding, but they weren’t suddenly able to extrapolate from that to go and book you a flight, say, or go away and organise an event that actually works.

A senior staff member at an AI company recently told me that, for them, this overall experience actually updated them towards longer timelines to artificial general intelligence. Because until then, that possible generalisation from easily checkable to non-checkable domains had been one plausible path to really rapid — perhaps unexpectedly rapid — capabilities gains. And now he saw that that was basically ruled out.

A lot of people think that this autonomy issue is changing right now with the arrival of Anthropic’s Claude Opus 4.5 and Claude Code, and, as of January 2026, Claude Cowork. But even if that does pan out as much as people are hoping and some people are expecting, it’ll be because Anthropic trained its models on these autonomy tasks specifically, not because of magical generalisation from reasoning tasks that we had originally hoped would get us those kinds of capabilities sort of for free.

There are two big ways that reasoning models got so much better at solving a particular kind of problem.

One was actually being better at reasoning — basically being smarter and more logical and able to maintain a thread for a decent amount of time — and the other was that they were given much longer to think through each question they were asked, where previous models had mostly not been given thinking time at all; they’d more or less just had to blurt out the first thing that popped into their head when they were asked a question.

Early on with reasoning models, it was kind of hard to tell how much work was being done by the first thing, actually being smarter, versus the second thing, so-called “inference scaling.” And that question mattered enormously, because it’s really expensive to have LLMs think for a lot longer every single time you want them to answer something.

The thing is, we could get this big proportional increase in thinking time in 2024 and 2025 because we’d basically been starting from zero. But while it was affordable to go from giving models zero minutes of thinking time up to one minute of thinking time, there actually aren’t enough computer chips in the world to go on and give models 10 minutes or 100 minutes to think in order to give slightly better answers, at least not for normal situations. And that fact would make the gains from increasing thinking time more of a one-off, not a trend that could carry on from 2024 to 2025, and into 2026 and 2027.

And indeed, it does appear that more than two-thirds of the improved performance of reasoning models came from giving them more time to think. And unfortunately, that’s not a trick we can pull off again, not until we go away and actually manufacture more and faster computer chips — which does happen, but doesn’t happen at anywhere near the rate that we were able to scale up thinking time before. This realisation meant that analysts came to expect slower improvements in AI capabilities going forward.

Past guest of the show Toby Ord has done the best public analysis of this that I’m aware of. It’s a little difficult to do, because a lot of the numbers are confidential inside the companies, but he figured things out from what he could find, and we’ll link to some of those articles in the show notes.

You might also recall this very influential graph showing that AIs can successfully complete all longer and longer software engineering tasks that came out of the organisation METR. Now, this is absolutely true, but a big part of that is being driven by the models being given access to way more thinking time to try and complete these tasks than they’d ever been given before — so the exponential increases in the length of tasks that can be completed that we saw have come with commensurately exponential increases in cost, so much so that in some cases these AI agents maybe cost about the same amount to run for an hour as it would actually cost you to hire a human software engineer: hundreds of dollars, in fact. And at that price, it wouldn’t be anywhere near economically rational to go ahead and scale up their thinking time another tenfold, up to thousands or tens of thousands of dollars — not in the immediate future anyway. So that is a reason to think that progress in 2026 and 2027 won’t necessarily come at the same pace that we saw in 2025.

So it stopped looking like we could scale up thinking time like we had been doing before, but maybe we could instead scale up reasoning training, which is more like a fixed cost rather than a cost that you have to pay every single time you have a question.

Unfortunately, that turned out not to be working as well as people had hoped in early 2025 either. It’s hard to pin down exactly, because the details of AI model training are super commercially sensitive, so they don’t literally publish the numbers that you might want to have. But Toby Ord estimates that the compute efficiency of this kind of reinforcement learning might be literally one-millionth as high as it was back in the “predict the next word” era or the pre-training era. That is a huge penalty, as you can imagine.

The trouble with the method is that reinforcement learning works by having the AI generate lots and lots of attempts to solve a really difficult coding or maths or philosophy problem. And whenever it does manage to get the right answer, we say, “Great, yes. Do more of whatever you were doing that time around.” This clearly does work — the models did get much better in these domains — but it requires a lot of computation to squeeze out a relatively modest amount of education or learning.

The reason is that, unlike with training models on accumulated human knowledge scraped from books or internet posts or GitHub or whatever, here it’s the AIs themselves that have to make the content they’re attempting to learn from — which includes making vast numbers of garbage, failed attempts to solve problems that ultimately go nowhere. And then at the end of each of these attempts, all the AI gets is “you got the right answer” or “you got the wrong answer.” But often they’ve been reasoning for hundreds of pages: what part of the reasoning that it went through was the part where it went off in the wrong direction? Or what part was the section where it made the breakthrough that led it to get the right answer? It gets no guidance on that kind of thing. Someone memorably described all this as an AI trying to suck intelligence through a tiny straw.

The bottom line is that we got a big boost in capabilities by taking this kind of reinforcement learning in confirmable domains from nothing to where it is now — but we just don’t have the computer chips around in the world to scale up reinforcement learning another thousandfold in order to get another similarly large leap in performance.

Let’s recap. Yes, we did get a big performance boost by scaling thinking time, and we got a lot of value out of scaling reinforcement learning in maths and coding and so on. But as these other facts that I’ve been talking about became apparent through 2025, people stopped believing that progress would remain as fast in 2026 as it had been up until then, and that led to a wave of pessimism.

I’ve been trying to explain why I think people’s opinions shifted, but if I’m honest with you, I don’t think that I really am that confident that the line of reasoning is right. And that’s because the AI companies always scale up one thing to improve performance until it hits diminishing returns, but then they find something else to scale up.

They famously massively scaled up the compute that went into training models to predict the next word, and that worked great. But then it started to hit diminishing returns as they had scaled it up 10x, 100x, a thousandfold.

Then the bigger focus became scaling up reinforcement learning from human feedback to make the models act more like helpful assistants that actually did things for you. And that worked great: it made a big difference until it also started to hit diminishing returns.

So then they naturally moved on to throwing compute at inference scaling and reinforcement learning for reasoning, as I was just describing. Each individual thing, as they scale it up 10x, 100x, 1,000x, 10,000x, the returns always peter out. But so long as there’s always something else to move on to, then the big-picture trend will remain one of steady improvement like we’ve seen before.

I’m sure their research teams are feverishly working to figure out other ways to efficiently convert computer chips into smarter and more useful and more capable AI models. That’s the entire job of their research. Will they succeed again for the fourth or fifth time? Or have they kind of run out of tricks for now, and we might have a couple of years to wait? That is the fundamental unknown that everyone, both inside and outside the companies, is more or less forced to repeatedly speculate about — until they either do or they don’t.

Other longstanding reasons AGI could take a good while [00:11:13]

Rob Wiblin: So those were some technical updates, new technical results. But there are a lot of worries that people have always had that also became more salient in the second half of 2025. Here are a couple that stand out to me.

First, there was an ever-growing gap over that time between what AI models seemed like they could do in demos and how much they were actually upending most workplaces and the world around us and our personal lives. This peculiar situation was summed up by the podcaster Dwarkesh Patel as, “Models keep getting more impressive at the rate the short timelines people predict, but more useful at the rate the long timelines people predict.”

I think this growing gap basically made analysts, made people begin to just trust their own judgement about how much something that seemed really impressive on the screen when they were talking to it, how much that could actually make a difference and increase productivity in real-world situations.

One reason for that failure to transfer to real applications could be the second point: AIs just clearly do not learn in the same way that humans do. Whatever our weaknesses, humans really do quickly get a lot better at stuff with just a couple of samples basically. We also just build up and accumulate new knowledge and new skills over time. And because AIs just don’t all do that, that means that unlike with a new human hire, they don’t get way more capable in the first few months working in a job as they figure out what works and what doesn’t. They just plateau really quickly.

Some people think that cracking this so-called “continual learning” is the key to unlocking way more usefulness from AI. But notably, we didn’t see much visible progress on that in 2025. So for some people, that was also a bearish indicator.

Finally, let’s talk about automation of AI research and development in particular. That looms especially large in this conversation, because if you can fully automate that, then maybe you would set off a recursive self-improvement loop: where AIs design better AIs, they go on to design better AIs, and pretty quickly humans kind of fade into the background and are progressively barely involved in AI development.

In my opinion, and I think most people’s opinions, it would be a really big deal if you could pull off fully automated AI research and development. But as people swung towards pessimism, a few arguments resurfaced and got a lot more discussion as to why AIs getting better at software engineering in these task timelines studies may not lead to fully automated AI research and development particularly soon at all.

First, AI companies are mostly not made of software engineers. There’s a lot of other stuff that’s going on. In particular in the case that we’re thinking of: other aspects of thinking about and experimenting on artificial intelligence that just are not software engineering. So even if software engineering, the thing that we’re testing in these benchmarks, became effectively free and unlimited and instant to do, arguably the whole process of AI research and development would pretty quickly get bottlenecked somewhere else and might only have been sped up quite modestly.

Secondly, as we improve AI, it gets harder and harder to find further improvements, because like with all similar things, we’ve plucked the low-hanging fruit. And that means that potentially we actually need a lot of AI assistance and tooling just to keep up the same rate of progress we had in the past. So if you observe that an AI company now, almost all of its code is being written by AI — 90%, 95% — well, maybe all that’s doing is allowing them to stay at the same research speed that they had before, not get faster as you might kind of naively expect when you first hear that.

This last point can be pretty material — it can pack a punch. The people behind the AI 2027 scenario, they missed this factor in their first round of modelling a year ago and factoring it into a recent update pushed out their timelines by one to two years — which, for those folks, given how quickly they’re expecting things to progress, that actually is quite a large adjustment.

So what’s the upshot of all of these updates? [00:14:47]

Rob Wiblin: So what was the upshot of all of these updates I’ve talked about so far?

At the start of 2025, forecasters on the prediction market Metaculus, forecast the arrival of strong AGI in July 2031. So I guess they were medium-timelines folks. That forecast has since moved out to November 2033. That’s a 2.5-year extension that occurred over the course of one year, which I think is a fair reflection of the mood in the AI industry. It’s not cataclysmic, it’s not an enormous delay, but people definitely started to think things are going to take a couple of years longer than they had at the start of 2025.

One thing worth knowing and squirrelling away in your memory, if you haven’t heard it already, is that the 2028–2032 window might be quite a make-or-break period for developing AGI or recursively self-improving AI.

The reason for that is that, up until that point, the AI industry will have been able to expand the inputs going into it a lot just by sucking in computer chips and electricity and technical stuff that were previously going towards or working on non-artificial-intelligence-related things. But if current rates of growth of those inputs continue, by 2032 AI will already be a huge fraction of all of the computer chips and electricity and tech staffing — there just won’t be that much slack left for them to absorb from the rest of the world.

And by that date, financing could even get kind of tricky by then, because the next scaleup might be a single AI model that costs $1 trillion to train, or $10 trillion to train. If AI hasn’t by that point really blown people away and convinced investors that it’s going to replace human labour on a massive scale, that is a lot of money to be throwing at something not knowing whether or not it’s going to pan out.

That’s not to say that even if it didn’t happen by 2032, that we wouldn’t go on and develop AGI eventually. I think almost certainly we would. We would probably just be in for a bit of a slower grind. And it would be a grind that’s driven above all by getting access to more compute, by building more fabs that manufacture computer chips, and by manufacturing more chips and making each of those chips more efficient. And that is a rapid progress in the scheme of ordinary things, but not as fast as we’ve been able to expand inputs of all of these different kinds so far.

5 reasons the radical pessimists are still wrong [00:16:54]

Rob Wiblin: I’ve been trying to make sense of why it is that technology people brought forward their AGI timelines a whole lot in early 2025, and then in the second half of the year pushed them out a whole lot again.

But out in broader society, you can find a whole separate narrative about AI that feels like it barely interacts with anything that I’ve been discussing. It’s a narrative that I think particularly circulates among media and academic types. And the story that it tells is that GPT-5 was a massive failure that showed AI progress has more or less stopped, and in any case, AI doesn’t make people more productive, and it’s basically useless. On top of that, it costs more to deliver than people are willing to pay for it or are paying for it now, and perhaps the AI companies might be on the verge of bankruptcy any day now, so bad is their business model.

It’s a perspective that I think is clearly completely misguided, and I’m going to give you five reasons why I think that.

Firstly, the Epoch Capabilities Index — Epoch is this great think tank; they collect lots of data about AI capabilities, inputs, all of that, and you should definitely check them out if you’re interested in this topic — tries to look at as many different AI models as possible on as many different capabilities benchmarks as possible, going back as far as we can measure, rather than cherry-picking individual results.

And it finds that, if anything, AI progress has sped up in recent years. They report that the performance of the best AI model available at any point in time increased twice as fast after April 2024 as it was increasing before.

I think we could maybe look at the longer-term graph and say perhaps it’s just a linear increase. There weren’t so many data points back in 2022 and 2023, so it’s a little bit hard to say. And if there really was a doubling in rates of progress, probably much of that was down to the inference scaling that we talked about earlier, something that we probably can’t keep up at the same pace. But I think this really does basically rule out the idea that AI progress has slowed down, let alone stopped completely. The Index puts GPT-5 and other recent models right in the middle of that recent faster trend.

So my interpretation is that behind all of the noisy swings in sentiment — people suddenly becoming optimistic and then horribly pessimistic — AI has neither gone to the moon nor has it hit a wall. Instead, it’s just gradually but relentlessly been getting a bit more useful every month for years now.

My second argument just stems from my experience using these models. Sometimes I hear people say that AI, it’s just not useful, people don’t want it — and I just want to ask them what the hell they are smoking. I effectively use AI for hours a day now, as a copilot and a thought partner. It allows me to get up to speed on things quicker, to learn things faster, to put my finger on exactly the thing that I don’t understand and get the answer to it. It also helps me get drudge work done much more quickly than before so I can get onto more interesting stuff.

It’s also, as so many people have found, a great place to get advice on health issues, financial planning questions, social situations, whatever thing you’re mulling over in your head. It recently helped me to diagnose, just as one example of tonnes that I’m sure people could give, this longstanding issue I had with my nose being congested all the time. I figured out what the issue probably is, and figured out what I should do in order to mostly get rid of it.

Now, to be sure, it’s usually not as good or reliable as the best human expert on these things — but most of us, most of the time, can’t turn around and get the best doctor or financial advisor or therapist or whoever to talk to us for as long as we like, for free, more or less. I think this is a huge change from the end of 2024. Back then I was kind of struggling to figure out a practical way to make use of these models, as impressive as they seemed on paper.

So sometimes I think maybe people’s impressions are just way out of date. And if they decided they don’t like AI and they stopped trying it out after that point, and they’re not willing to pay for the actual cutting-edge models now, that might keep them abreast of what AI is actually capable of. I think that’s the most generous explanation that I could give for this kind of attitude anyway.

Third, and this one is really important: earlier I emphasised the growing compute and financial cost of the very frontier reasoning and agent capabilities that exist anywhere. And I pointed out that the most cutting-edge AI agents might cost more to operate than even a human software engineer. But near-frontier capabilities are often much, much cheaper. Gemini 3 Flash, for instance, performs on most tasks within a percentage point or two of Gemini 3 Pro, and it costs just a quarter as much to run. It answers questions much faster as well, so a lot of people just prefer it for that reason.

And the more out on the tail you go, the more extreme these cost reductions can become. Last year, people who regularly listen to the show know that I discussed with Toby Ord how in late 2024 OpenAI passed a really very difficult reasoning benchmark, ARC-AGI-1, by spending fully $4,500 on compute per question in the test. The model would go away and write notes the length of the Encyclopaedia Britannica trying to answer these questions — questions that you or I in fact could answer very easily.

Well, a year later, OpenAI managed to achieve the same performance for $11, a 400-fold decline. So basically, there is a very steep cost performance curve at the frontier, but most of us don’t need the absolute frontier — and even if we do, costs at that frontier are falling incredibly quickly.

Fourth, there was a fascinating study that came out very recently looking at predictions a bunch of relatively bullish short-timelines AI folks made about how AI would go back at the start of 2025. On the questions of how well AI would do on different intelligence measures, they were basically right, on average at least. Sometimes they overestimated, sometimes they underestimated, but on average they were basically on the money.

The one place they got things significantly wrong was on the question of how much revenue OpenAI, Anthropic and xAI would earn selling their products to customers. These forecasters, who are bullish on AI capabilities to be sure, predicted that it would go up 2.5 fold to an annualised revenue rate of $16 billion. But in actual reality, it went up almost fivefold to $30 billion. And that’s in an industry that’s already quite significant. It’s hard to look at this kind of growth and escape the idea that this is a product a lot of people really want and that they use quite frequently and that they’re willing to pay cold, hard cash for.

My fifth point — and this is the last one; we’re getting to the end, eventually — you might be under the impression that AI companies are selling access to their AI models at below what it costs to supply them in order to pull in customers, get them hooked; a bit like Uber did back in the day. But that’s not the case: the companies are clearly making money on each additional paying user who signs up.

Now, there’s also the essential issue of fixed costs: they need to make enough profit from those customers to pay the fixed costs of their sales and marketing team, the research and development teams (the staff can be very expensive), and of course the cost of the compute to train the models in the first place, which is one of their biggest costs. But they’re making a profit on each new customer, and they’re growing revenue fivefold a year. That sounds like they’re on a reasonable track to become profitable to me. And that’s even setting aside the possibility that they might fully replace human labour or build a superintelligent machine god at some point, which I think would surely change the game.

Even long timelines are short [00:23:54]

Rob Wiblin: So that is all a lot to digest. I’ve been trying to give an overview of the things that we learned last year, but where does that leave us overall?

Well, personally I would be pretty shocked if we got fully automated AI research and development next year. 2028: I guess it’s imaginable, but it’s going to require some surprising breakthroughs or an acceleration beyond what we’re seeing right now. 2029, 2030: it begins to feel plausible. At least we can’t rule it out if current trends continue and we don’t hit any significant new roadblocks. But there’s also a very real chance that we’re in for a significantly longer and slower takeoff.

But let’s put this into a broader context. Previous guest of the show Helen Toner wrote an article last year titled “‘Long’ timelines to advanced AI have gotten crazy short](https://helentoner.substack.com/p/long-timelines-to-advanced-ai-have).” She pointed out that the longtime AGI sceptics like Gary Marcus and Yann LeCun — who previously thought an AI that could replicate a human worker was decades away, if it was going to come at all — now think it’s probably about 10 years away. And that’s pretty typical as well of moderates within the leading AI companies, as well as medium-timelines AI safety folks, like for instance Toby Ord, who I’ve been talking about.

But the idea that in 10 years we’ll have this revolutionary technology, a machine that can do all of the intellectual work that humans can do, which continues getting smarter, faster, and cheaper every year at the rate that computers do, that is still shocking and incredibly consequential if it’s the case. Two years is clearly nowhere near enough time to prepare the world for the social, political, economic, military, and epistemic upheavals that that would bring. But 10 years? Ten years isn’t comfortable either.

And on that cheerful note, I’ll speak with you next time.

Related episodes

About the show

The 80,000 Hours Podcast features unusually in-depth conversations about the world's most pressing problems and how you can use your career to solve them. We invite guests pursuing a wide range of career paths — from academics and activists to entrepreneurs and policymakers — to analyse the case for and against working on different issues and which approaches are best for solving them.

Get in touch with feedback or guest suggestions by emailing [email protected].

What should I listen to first?

We've carefully selected 10 episodes we think it could make sense to listen to first, on a separate podcast feed:

Check out 'Effective Altruism: An Introduction'

Subscribe here, or anywhere you get podcasts:

If you're new, see the podcast homepage for ideas on where to start, or browse our full episode archive.