Effective altruism

How the 80/20 principle applies to doing good

It sounds obvious that it’s better to help two people than one if the cost is the same. However, when applied to the world today, this obvious-sounding idea leads to surprising conclusions.

In short, we believe we need a new approach to having an impact: effective altruism.

Modern levels of wealth and technology have given some members of the present generation potentially enormous abilities to help others, while our common-sense views of what it means to be a good person have not caught up with this change.

This means that some actions that are widely considered to ‘do good’ have dramatically greater positive consequences than others.

For instance, the UK’s National Health Service and many US government agencies are willing to spend over $30,000 to give someone an extra year of healthy life.1 This is a great use of resources by ordinary standards.

However, research by GiveWell has found that it’s possible to give an infant a year of healthy life by donating around $100 to one of the most cost-effective global health charities, such as the Against Malaria Foundation (AMF). This is about 0.33% as much. This suggests that at least in terms of improving health, one career working somewhere like AMF might achieve as much as 300 careers focused on typical ways of doing good in a rich country.

These kinds of health programmes offer such a good opportunity to do good that even the most prominent aid sceptics have offered few arguments against them.

This is not unique to health programmes. When we’ve looked at other ways of doing good, this pattern tends to be replicated: the most effective ways to help usually seem much better than what’s typical. For instance:

- Among ways individuals can combat climate change, there are huge differences in how much different actions reduce CO2.

- Within US social programmes, the most cost effective are far more effective than the median.

- Within politics, the best get out the vote methods work far better than typical ones.

Indeed, many social programmes have little impact at all, which by itself creates a significant difference between the best and typical.

In our own work, we’ve argued that the impact of different career paths depends on:

- How pressing the problems you work on are

- The scale of the contribution the path lets you make to tackling those problems

- Your degree of personal fit with the path

And in our foundations series, we argued that the best vs. typical options within each factor often seem to vary by a factor of 10 and sometimes a lot more (i.e. the paths with the most leverage open to you have more than 10 times the leverage of a more typical option, the most effective solutions make 10 times more progress on the problem per year of work, etc.). And since the overall impact of a career is given by the multiple of the three factors, the total variation in impact is even larger.

This wide spread of outcomes is also probably what we should expect to find.

A trait like height follows a ‘normal’ distribution: the tallest people are only about 50% taller than the average. A trait like income, however, follows a ‘fat tail’ distribution: the highest-earning people earn thousands of times more than average. This concept has been popularised as the ’80/20 principle’ — which says that 80% of outcomes are caused by 20% of events — or as the idea that outcomes are dominated by ‘black swan events.’

We expect that the distribution of the expected impact of different actions is more likely to be like income than height.

One reason for this is that if the outcomes of different actions are caused by the multiplication of several factors — as they often are — then the value of different actions will end up as a heavy-tailed distribution (technically, a log-normal distribution).

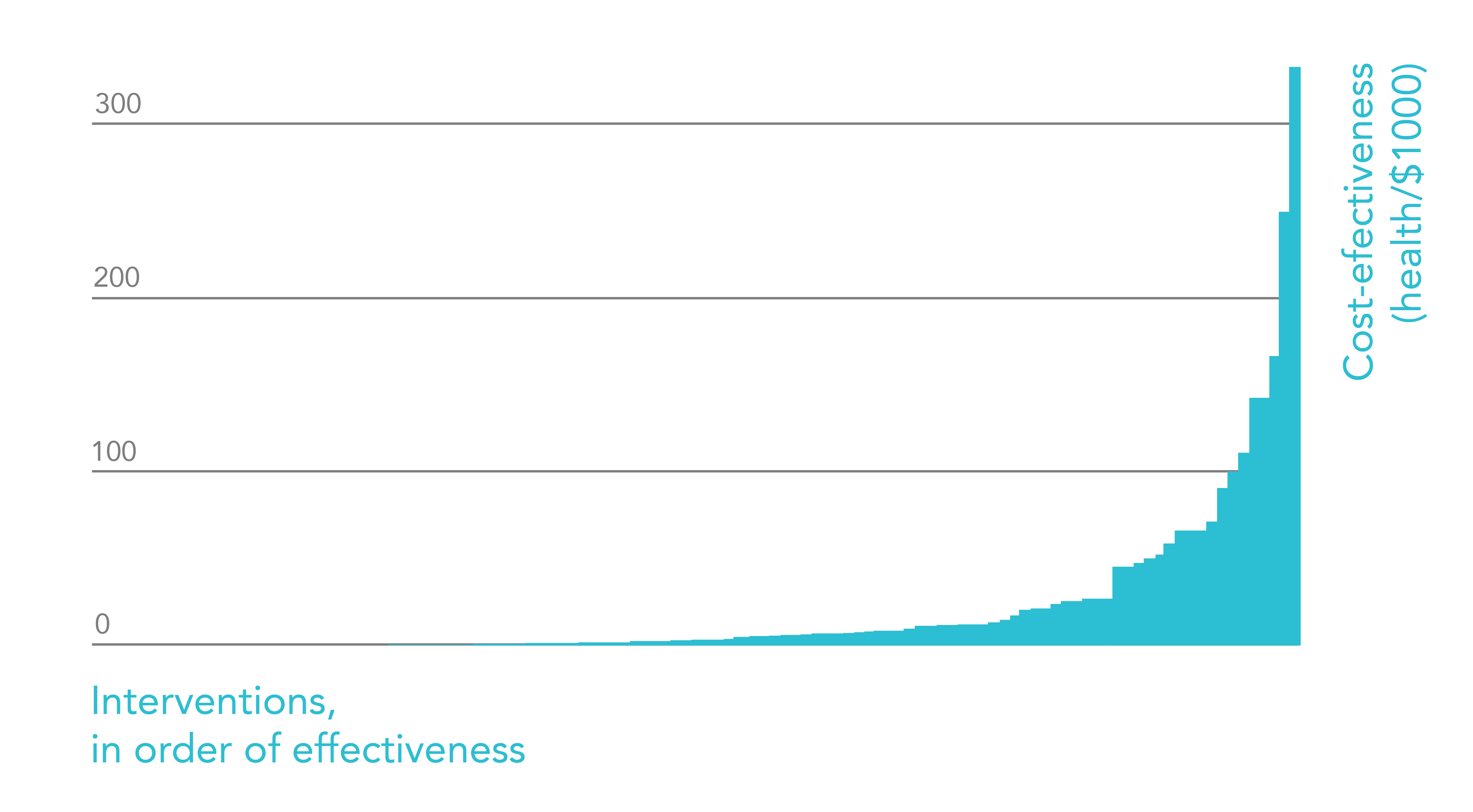

This is the pattern we see where we have good data. For instance, the cost effectiveness of ways to improve health in poor countries (measured with ‘cost per year of healthy life’) closely follows an 80/20 distribution.

Research by Open Philanthropy finds a similar pattern in other areas.

This means that if your aim is to impartially help others, and all else equal you’d prefer to help more people, your key concern shouldn’t just be to ‘make a difference’ — it should be to identify the very best ways to help among the options open to you.

This idea might sound obvious, but when we surveyed people on how much more effective they think the best charities are compared to the median, a typical response was that the best charities are only 66% more effective; whereas instead it seems like the difference is more like 10,000%. So, the difference between the best and typical ways of helping are much larger than ordinarily supposed.

This idea also has some radical implications.

One big implication is that it means that people who want to do good could achieve far more than they do today, simply by paying more attention to the effectiveness of their options.

For instance, if some ways of doing good achieve 100 times as much as others, then we could be making 100 times as much progress on global problems without using any more resources. Or to put it another way, it would be like increasing the number of people focused on doing good by 100 times.

As an individual, it really seems possible to save the lives of tens of others, or even to play a role in reducing the risk of the end of civilisation or shaping the most important century.

Perhaps an even bigger implication is that we need to rethink what it means to be a good person.

Our ethics are very focused on not doing wrong, rather than doing more good. This made sense in a pre-modern world where we didn’t have much power to do good. But today it’s missing the most important part of the picture.

This is clear in discussions of climate change, where most attention is given to how individuals can reduce their personal climate footprint. But if you try to reduce your personal climate footprint, the best-case scenario is avoiding around 5-20 tonnes of emissions per year (roughly the average emissions of the citizens of a rich country) — often at great expense.

Instead we should be asking, “What’s the best thing I can do to tackle climate change?” By making well-targeted donations, through carefully targeted advocacy efforts, or using your career to tackle climate change, we think you could do vastly more than avoid 20 tonnes of emissions per year, and probably with less personal sacrifice.

Rather than not doing wrong, modern ethics should be focused far more on how we can best do good.

So how can we best do good? Despite the vital importance of this question, it’s received very little direct study. We need a new field that applies our best methods for seeking truth to answer it.

And it turns out that while ‘helping two people is better than one’ and ‘let’s use reason and evidence to find the best ways to help’ sound like obvious principles, if you follow them where they lead, you end up in some pretty weird places. It’s perhaps similar to how using reason and evidence to search for truth led us to quantum mechanics.

This means we also need to rethink which actions actually do the most to help.

These are the insights behind the ‘effective altruism’ movement, which we helped to found in 2012. Effective altruism is the search for the best ways to help others. It can be divided into two projects:

- A research field aimed at finding the actions that achieve the most good.

- A community of people around the world who work together to put the ideas in practice and have a positive impact.

To think effective altruism is worthwhile in principle, all you need to believe is that it’s good to help others, and that you’d prefer to help more people rather than fewer.

If we combine this with the opening claim that some ways of helping are much more effective than others, but they’re not what people are focused on today, then it implies we need a new field of research to search for the best ways of helping, and that by applying the findings, we can do a lot more good.

We see 80,000 Hours as a project within the broader project of effective altruism. Our focus is on finding the career paths and strategies that enable you to best help others, but effective altruism in general is about all ways of doing good: through donations, career change, volunteering, consumption, campaigning, etc.

There’s now a global community of thousands of people trying to put these ideas into practice, and tens of billions of dollars committed to the approach. Here’s how to get involved.

Learn more about effective altruism

You have a choice of introductions:

- Our podcast series: Effective Altruism: an introduction

- An online article: An Introduction to Effective Altruism

- An academic article: Effective Altruism by Will MacAskill

You can also read Doing Good Better, which is by our co-founder and philosopher, Will MacAskill. Steven Levitt, the author of Freakonomics, said the book “should be required reading for anyone interested in making the world better”. The book is more focused on measurable global health interventions than we are today, but discusses the same principles. Will MacAskill also has a more recent TED talk.

Further reading

- What is the core idea of effective altruism? an interview with our founder, Benjamin Todd

- Doing Good Better by Will MacAskill

- The guiding principles of effective altruism by the Centre for Effective Altruism

- Effective altruism by GiveWell

- Common objections to effective altruism

- Misconceptions about effective altruism

Notes and references

- “Below a most plausible ICER of £20,000 per QALY gained, the decision to recommend the use of a technology is normally based on the cost-effectiveness estimate and the acceptability of a technology as an effective use of NHS resources.” From Guide to the methods of technology appraisal 2013, by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Archived link↩