#42 – Amanda Askell on tackling the ethics of infinity, being clueless about the effects of our actions, and having moral empathy for intellectual adversaries

#42 – Amanda Askell on tackling the ethics of infinity, being clueless about the effects of our actions, and having moral empathy for intellectual adversaries

By Robert Wiblin and Keiran Harris · Published September 11th, 2018

Consider two familiar moments at a family reunion.

Our host, Uncle Bill, is taking pride in his barbequing skills. But his niece Becky says that she now refuses to eat meat. A groan goes round the table; the family mostly think of this as an annoying picky preference. But were it viewed as a moral position rather than personal preference – as they might if instead Becky were avoiding meat on religious grounds – it would usually receive a very different reaction.

An hour later Bill expresses a strong objection to abortion. Again, a groan goes round the table: the family mostly think that he has no business in trying to foist his regressive preferences on other people’s personal lives. But if considered not as a matter of personal taste, but rather as a moral position – that Bill genuinely believes he’s opposing mass-murder – his comment might start a serious conversation.

Amanda Askell, who recently completed a PhD in philosophy at NYU focused on the ethics of infinity, thinks that we often betray a complete lack of moral empathy. Across the political spectrum, we’re unable to get inside the mindset of people who expresses views that we disagree with, and see the issue from their point of view.

A common cause of conflict, as above, is confusion between personal preferences and moral positions. Assuming good faith on the part of the person you disagree with, and actually engaging with the beliefs they claim to hold, is perhaps the best remedy for our inability to make progress on controversial issues.

One seeming path to progress involves contraception. A lot of people who are anti-abortion are also anti-contraception. But they’ll usually think that abortion is much worse than contraception – so why can’t we compromise and agree to have much more contraception available?

According to Amanda, a charitable explanation is that people who are anti-abortion and anti-contraception engage in moral reasoning and advocacy based on what, in their minds, is the best of all possible worlds: one where people neither use contraception nor get abortions.

So instead of arguing about abortion and contraception, we could discuss the underlying principle that one should advocate for the best possible world, rather than the best probable world. Successfully break down such ethical beliefs, absent political toxicity, and it might be possible to actually figure out why we disagree and perhaps even converge on agreement.

Today’s episode blends such practical topics with cutting-edge philosophy. We cover:

- The problem of ‘moral cluelessness’ – our inability to predict the consequences of our actions – and how we might work around it

- Amanda’s biggest criticisms of social justice activists, and of critics of social justice activists

- Is there an ethical difference between prison and corporal punishment? Are both or neither justified?

- How to resolve ‘infinitarian paralysis’ – the inability to make decisions when infinities get involved.

- What’s effective altruism doing wrong?

- How should we think about jargon? Are a lot of people who don’t communicate clearly just trying to scam us?

- How can people be more successful while they remain within the cocoon of school and university?

- How did Amanda find her philosophy PhD, and how will she decide what to do now?

Get this episode by subscribing to our podcast on the world’s most pressing problems and how to solve them: type 80,000 Hours into your podcasting app. Or read the transcript below.

The 80,000 Hours podcast is produced by Keiran Harris.

Highlights

…I often think that we should have norms where if you don’t understand people relatively quickly, you’re not required to continue to engage. It’s the job of communicators to clearly tell you what they mean. And if they feel like it’s your job to-

Robert Wiblin: They impose such large demands on other people.

Amanda Askell: Yeah. … if you communicate in a way that’s ambiguous or that uses a lot of jargon, what you do is you force people to spend a lot of time thinking about what you might mean. If they’re smart and conscientious reader, they’re going to be charitable and they’re going to attribute the most generous interpretation to you.

And this is actually really bad because it can mean that … ambiguous communication can actually be really attractive to people who are excited about generating interpretations of texts. And so you can end up having these really perverse incentives to not be clear. …

… there are norms in philosophy. They’re not always followed, but it’s one thing that I always liked about the discipline is you’re told to always just basically state the thing that you mean to state as clearly as possible. And I think that’s like a norm that I live by. And I also think that people appreciate when reading.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah, this is getting close to a hobby horse of mine. I’m quite an extremist on this communication issue. When I notice people who I think are being vague or obscurantist – that they’re not communicating as clearly as they could – my baseline assumption is that they’re pulling a scam. They’re pulling the scam where they’re expecting other people to do the work for them and they’re trying to cover up weaknesses in what they’re saying by not being clear.

Maybe that’s too cynical. Maybe that’s too harsh and interpretation. We were saying we should be charitable to other people but honestly my experience very often just has been even after looking into it more, that has been my conclusion that especially people who can’t express things clearly but claim that they have some extremely clear idea of what you’re trying to say. I feel that they’re just pulling a con.

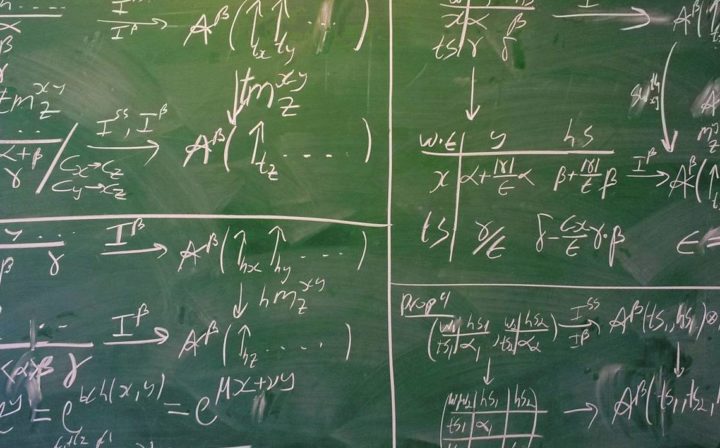

I think the reason why these questions are important is because they demonstrate inconsistencies with fundamental ethical principles. And those inconsistencies arise and generate problems even if you’re merely uncertain about whether the world is like this. And the fact that the world could in fact be like this means that I think we should find these conflicts between fundamental ethical axioms quite troubling. Because you’re going to have to give up one of those axioms then. And that’s going to have ramifications on your ethical theory, presumably also in finite cases. Like if you rejected the Pareto principle, that could have a huge effect on which ethical principles you think are true in the finite case.

But, I do have sympathy for the concern. I don’t think that this question is an urgent one, for example, and so I don’t think that people should necessarily be pouring all of their time into it. I think it could be important because I think that ethics is important and this generates really important problems for ethics. But I don’t necessarily think it’s urgent.

And so I think that one thing that people might be inclined to say is, “Oh this is just so abstract and just doesn’t matter.” I tend to think it does matter, but the thing maybe that you’re picking up on is it’s possibly not urgent that we solve this problem. And I think that’s probably correct.

If you think that there are really important unresolved problems, then things that give you the space at some point in the future to research the stuff can be more important.

These issues might not be urgent, but at some point it would be really nice to work through and resolve all of them and so you want to make sure that you leave space for that and you don’t commit to one theory being true in this case. And I think that the lessons of impossibility theorems and ethics that are important are mainly that ethics is hard and that you shouldn’t act as if one ethical theory or principle or set of principles is definitely true because there are a lot of inconsistencies between really plausible ones. And so I think that’s a more general principle that one should live by, and maybe these impossibility results just kind of strengthen that.

I’ve talked a little bit about moral value of information in the past and I think that the main thing that I kind of concluded from it was that it’s very easy to take this kind of evidence based mindset when it comes to doing the most good. We are like, let’s just take these interventions, for which I have the most evidence about what the nature of their impact is, and let’s just invest in those or you can take a kind of more expectations-based kind of approach where you say, “Well, actually, what we should do is we should run some experiments and we should try out various things and see if they work because we just don’t have a huge amount of information in this domain.”

And if you take that kind of attitude, you can end up, kind of, investing in things a bit more experimentally and I think that there’s potentially a better case to be made for that than people have appreciated and so that might be one consequence of this is just, “Hey, the ethical value of information is actually higher than we thought and maybe we should just be trying to find new ways of gaining a bunch of new information about how we can do good.

We often seem to betray a kind of complete lack of what I call moral empathy, where moral empathy is trying to get inside the mindset of someone who expresses views that we disagree with and see that from their point of view, what they’re talking about is a moral issue and not merely a preference. The first example is vegetarianism where you’ll sometimes see people basically get very annoyed, say, with their vegetarian family member because the person doesn’t want to eat meat at a family gathering or something like that. I think the example I give is, this makes sense if you just think of vegetarianism like a preference.

It’s just like, “Oh, they’re being awkward. They just have this random preference that they want me to try and accommodate.” It’s much less acceptable if you think of it as a moral view. You see this where people are a bit more respectful of religious views. So if someone eats halal, I think that it would be seen as unacceptable to … people wouldn’t have the same attitude of, oh, how annoying and how terrible of them.

…I find people in conversation much more happy and just much more willing to discuss with you if you show that you actually have cared enough to go away and research their worldview and you might be like, “Look, I looked into your worldview and I don’t agree with it, but I’ll demonstrate to you that I understand it.” It just makes for a much more friendly discussion basically because it shows that you’re not like, “I don’t even need to look at the things that you’ve been raised with or understood or researched. I just know better without even looking at them.

Articles, books, and other media discussed in the show

- Amanda’s blog

- Amanda’s PhD Thesis: Pareto Principles in Infinite Ethics

- Amanda’s BPhil Thesis: Objective Epistemic Consequentialism

- The Moral Value of Information, Amanda’s talk at EA Global 2017: Boston

- Cluelessness by Hilary Greaves

- Pareto Principle on Wikipedia

- Multi-armed bandit on Wikipedia

- Algorithms to Live By: The Computer Science of Human Decisions by Brian Christian and Tom Griffiths

- When Brute Force Fails: How to Have Less Crime and Less Punishment by Mark Kleiman

- Infinite Utility by James Cain (introducing The Sphere of Suffering)

- With Infinite Utility, More Needn’t Be Better by Hamkins and Montero

- Down Girl by Kate Manne

Latest 80,000 Hours articles:

- Our career review of working as a congressional staffer

- Randomised experiment: If you’re genuinely unsure whether to quit your job or break up, then you probably should

- Psychology experiments in top journals – are they true?

- Should you play to your comparative advantage?

Transcript

Robert Wiblin: Hi listeners, this is the 80,000 Hours Podcast, where each week we have an unusually in-depth conversation about one of the world’s most pressing problems and how you can use your career to solve it. I’m Rob Wiblin, Director of Research at 80,000 Hours.

Before we get to today’s episode I just wanted to mention a few articles we’ve released lately.

I’ll put links to these in the show notes and blog post associated with this episode. If you want to skip this section jump ahead a minute or two.

Last week we launched a career review of working as a congressional staffer which covers the impact you might expect to have, various other pros and cons, and what are indicators that it’s a good personal fit. If you could see yourself pursuing a career in US politics you should check it out.

A few weeks ago I wrote up a summary of a randomised controlled trial that found people who were on the fence about whether to quit their jobs or make other changes to their lives. It then advised some of them to make the change, and others to stay the course. It found that in general people who changed their lives were happier six months later. The write-up goes into more detail and you should certainly read it before taking action on this basis.

You may have heard about a paper published 2 weeks ago reporting on the results of an effort to replicate 21 psychology papers published in the best journals, to figure out which effects were real and which weren’t. I made a quiz that describes the results of these 21 papers and invites you to guess whether that particular effect replicated or not.

It’s quite fun and so far 6,000 people have used it. We’re collecting data on what kinds of people have the most accurate guesses, which we’ll write up soon.

Finally, just yesterday we published a new and quite advanced article on whether or not it’s important to focus on finding your comparative advantage relative to other people in your professional community.

Alright, here’s Amanda.

Robert Wiblin: Today I’m speaking with Amanda Askell. Amanda recently completed a PhD in philosophy at NYU, one the world’s top philosophy grad schools with a thesis focused on Infinite Ethics. Before that, she did a BPhil at Oxford University, with her thesis being focused on objective epistemic consequentialism, quite a mouthful. She’s been involved in the effective activism community since its inception and blogs at rationalreflection.net.

Thanks for coming on the podcast, Amanda.

Amanda Askell: Thank you for having me.

Robert Wiblin: So, we plan to talk a bunch about your philosophy research and I guess, your views on philosophy PhDs and academic careers in general. But first, you finished your PhD defense a couple of weeks ago, right?

Amanda Askell: Yeah, last week.

Robert Wiblin: Okay, yeah. How did you find the PhD experience? Is it six years you spent at NYU?

Amanda Askell: Six and a half years I think, altogether.

Robert Wiblin: I mean I’ve heard that PhDs in the US are pretty painful. Is that kind of your experience?

Amanda Askell: I think it depends on your disposition. In some ways I think I’m maybe not the perfect disposition for a PhD. You have to be able to focus on many things at once if you want to kind of get a lot out of the program, I think. I tend to be much more kind of singular in my thinking. And so, I find it a little bit hard to spread my research across multiple topics. Whereas in the US you start out kind of doing many topics and then eventually focusing in on the thesis.

Robert Wiblin: I thought the challenge that most people had was focusing in their PhD. Because they kind of want to graze intellectually, but then they have to spend potentially years just getting to the forefront of one particular topic.

Amanda Askell: I think it depends on the kind of person you are. So, some people have this kind of magical ability to do a PhD and at the same time produce many different kinds of research while they’re doing their thesis. And I think I always saw that and thought, “Oh, that’s what I want to do. I want to be the kind of person that just produces many things while I’m doing my PhD.” And then I found towards the end that it was like, actually, if I want to get this PhD finished and do the research, I have to really just focus on this one thing.

So some people have this ability to focus on multiple things. But I always don’t have a problem with just focusing in on single research topic. It’s just that I wish I could kind of multitask, in that way I seem unable to.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah, I think you seem like one of the most conscientious people I know. Is this a potential downside of that? I’m trying to find any justification for my lack of conscientiousness.

Amanda Askell: This feels surprising to me. Because I think I can be conscientious about work but this can also mean neglecting things in ways that other people don’t. So I can be very non-conscientious about emails for example-

Robert Wiblin: Yeah.

Amanda Askell: As a result of this. So I just trade off. I just take conscientiousness from one area and I like erase it and I apply this to some other area, like my research. So that’s how I work. I’m like I have a pool of conscientiousness. And I have lots of emails that I haven’t responded to.

Robert Wiblin: I think most of the philosophers I know seem … They really fit the philosopher’s stereotype of kind of a bit having their heads in the clouds. Perhaps like, quite bad at life admin. Filing their taxes and answering their emails and buying food and cleaning their room.

Amanda Askell: Yeah.

Robert Wiblin: I guess you seem a bit like that.

Amanda Askell: Yes, I’m very like that.

Robert Wiblin: Do you think there’s a systematic reason why philosophers have to be that way?

Amanda Askell: I think that you have to carve out a space for research. So the kind of intense research that is involved both in PhDs but also later in research jobs, just needs kind of single minded focus on one topic. And I just find if I’m having to think about other things, it just divides my attention. And so I compartmentalize really heavily.

So I’m the kind of person where I’m like, I completely get rid of my emails. I’ll just snooze all of them until a given task is done. And I think if you don’t have that space, it’s just like you can’t get to that point where you can just focus fully on this very difficult problem in front of you. So I think it’s that, that people are inclined to just get rid of the other stuff in order to focus on problems.

Robert Wiblin: So, having finished your PhD, are you glad that you started it in the first place?

Amanda Askell: Oh, that is a tough question. I think in retrospect, I’m unsure whether I would do a PhD again, were I faced with the same choice that I had say, like six or seven years ago. Mainly … Not because I haven’t enjoyed the program and not because I haven’t learned a lot. It’s just a huge time investment. And it’s a time investment in the case of philosophy that’s quite singularly focused on one outcome. Namely, people are mainly focused on getting academic jobs. It’s somewhat unusual for people to do other things.

And so, if you have any uncertainty about whether that’s what you want to do, it can be quite risky. And, given the way that the job market is at the moment, it can be quite risky even if you think that that’s definitely what you want to do. So, I’m not sure that I … Yeah. I’m basically not sure that I would do it over again and perhaps not on the topics that I chose to focus on.

Robert Wiblin: Okay, well we’ll come back to talking about philosophy as a career track and what you’re going to do next later on in the episode.

But for now I wanna move onto the issue of moral cluelessness. So what is that problem.

Amanda Askell: Cluelessness is this problem that arises when you’re trying to make an ethical decision and there are immediate ramifications to your actions that you can just understand quite well. So I can distribute twenty malaria nets in this region and I can estimate the impact that will have in terms of malaria for those people.

But there are lots of effects of your actions that are just very difficult to predict. An example is you save the life of a woman and you don’t realize that the child that she’s carrying is going to grow up to be a terrible dictator who murders many people. So this was just a very unforeseen consequence of the action of saving the woman. Similarly you could save someone whose child grows up to save billions of people but it was an unforeseen consequence of the act of saving the woman which the direct impact of it was just saving that woman and saving her unborn child.

And the worry about this is essentially you may think, well, maybe things just kind of cancel out. So I have action A, which is saving the woman, and action B, which is not. It’s just very obvious that I should help the woman. I’m inclined to agree with that. So you say, well, she could have given birth to this person who ends up being a terrible dictator but she also could have given birth to this person who saves millions of lives. And so these probabilities of these kind of outlier events cancel out.

The problem of cluelessness, of a novel problem of cluelessness that has been talked about by Hilary Greaves for example is that in some cases it doesn’t seem like we can use this kind of principle of indifference, so it could be that my actions have ongoing ramifications that are simply not foreseen but I don’t have any reason to think that they’re equal across both of my actions.

So you think about the consequences of having this huge impact in a country by donating a huge amount of money and affecting its economy and affecting its people. There may be consistent impacts of that action that are not such that I can just think, oh yeah and it’s equally likely that that wouldn’t have happened or that the opposite would have happened. Rather it’s just I don’t know.

And so the problem of cluelessness is something like I shouldn’t necessarily think that there is equal probabilities of these outlier effects of unintended effects but nor do I have any information to go on about the likelihood or otherwise of these good long term effects versus these negative long term effects. And so it’s this real worry our degree of uncertainty of the long term unintended of direct impact of our actions.

Robert Wiblin: So for this to be a real problem does it have to be the case that these long term or indirect effects are much larger than the direct effect? That they’re likely to swamp it?

Amanda Askell: I’m not sure if it’s necessary for the problem. I’m trying to think about whether you can generate a smaller version of the problem. I think it’s likely that this is what’s generating the key worry. Is just that consequences of my actions are actually quite likely to be large as well because when we think about the fact that this was the causal chain that you’re setting off when you undertake an action like intervening in another country, it’s not when you actually expect the ramifications to be kind of small. It’s one where you do expect a kind of important long term impact and you may not be sure about the sign of that impact if you think that these unforeseen outcomes that are quite negative and quite positive and that you do not have enough information to be able to see how likely they are. So I think the presupposition is more that almost all of the outcomes are fairly large and as soon as you get further beyond a few years from now you start to be really uncertain about what they look like.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. I wonder if it’s worth pointing out how easy it would be for saving a single life to change the entire course of history, that this is not only possible but perhaps even probable that it could completely change the identities of all people and future generations.

Amanda Askell: Well yeah, a super fun … I think it gets called the ancestor’s paradox. That’s essentially think about how many grandparents you have and how many great grandparents you have and imagine that tree branching outwards. And it gets bigger and bigger as you go back in the generations. And imagine the number of people who have existed in history. It gets narrower and narrower. Our population has been increasing so as you go into the past it actually decreases. And obviously the reason for this is that there’s a lot of overlap between relations, so maybe it’s the case that your great great great grandparent is also your great great great something else. And because of this, if you go far enough back in history you can say, if this person had any living descendant then they are in fact the ancestors of everyone on earth and this is a really interesting effect when you think about it going forward because you should expect the same thing.

So one person, if they have living descendants far into the future will in fact be the ancestor of everyone. So, changing who they give birth to or changing whether they have children and whether they have living descendants can actually change the entire population of the world in the future. So, identities of agents are actually super delicate basically. And so yes if you save the life of one person they’re going to have children and have children’s children etc. there’s a really good chance you just changed the identity of everyone who exists, the entire population of humans that exist in the future, which is very interesting but it’s an example of how the cause of ramifications of your actions can actually be fairly massive.

Robert Wiblin: And also extremely unpredictable [crosstalk 00:52:16].

Amanda Askell: And very unpredictable. Yeah.

Robert Wiblin: Are there different forms of cluelessness that we should worry about, different kind of classifications?

Amanda Askell: The main classification that I’m aware of is this kind of new puzzle of cluelessness versus the original puzzle where the new puzzle is pointing out that it’s very difficult to use the principle of indifference in some of these cases, specifically the example used is effective altruism where you expect to have large and fairly consistent effects so it’s not merely what’s the possibility that this woman gives birth to a dictator versus she gives birth to someone fantastic and maybe you think that you should use the principle of indifference because the person could have been a dictator or they could have been a real benefit to humanity but rather that they have consistent effects but we just don’t know about them.

So that was an unpredictable outcome versus one that is a consistent outcome of your action that you shouldn’t think it was equally likely that the opposite outcome would have happened. So in changing a population, improving the lives right now of a population and therefore changing everything about the future economy of that country, that will in fact kind of good or bad for that country but you shouldn’t just say, oh well, fifty-fifty, it could either be good or either be bad but rather if you investigate you would find reasons for thinking that it’s more likely to be good than bad but right now you just have complete uncertainty about which is the case.

Robert Wiblin: But for it to matter it has to be possible, or you either have to believe already that it’s either probably positive or negative or it has to be possible for you to find out, right?

Amanda Askell: Yeah. If you think of the principle of indifference isn’t true here, that’s a principle that lets you just kind of assign really precise values to kind of outcomes and just say, well I have this really very positive outcome and this really very negative outcome. Both of them are possible and I’m gonna assign them the same probability. If you think that this cluelessness problem is a real problem, one thing you might say is I just can’t assign probabilities to these outcomes given my current evidence and in that case you should perhaps try to use imprecise probabilities or probability intervals or something like that.

Robert Wiblin: Wouldn’t you always have some kind of credence, some kind of probability attached to each outcome? You wanna move away from this simple bayesianism?

Amanda Askell: I mean I like this and the question mainly here is, can we say this is actually rational, what we’re doing. And so, one possible response for this is actually you do have reasons and we’re not merely appealing to a principle of indifference but rather we are thinking of all of the possible long term ramifications of our actions given our current evidence and we’re using that to make decisions and we’re going to try to discover more about those long term ramifications are.

So I think if you do it within a kind of precise framework you would probably just end up denying that we’re reasoning using the principle of indifference and you try and say, no, we actually have evidence about these long term outcomes and we either are or should be taking into account and the major update that we get from the problem of cluelessness is that we should really be trying to figure out more what the long term ramifications of our actions are because the fact that we can even look at cases like this and be unsure about the effects that our actions will have in, like, seventy years is fairly bad. Because it could be that there’s just these things that we could gain evidence about that are at the moment unforeseen and that are gonna negatively impact future populations.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. So, what’s this principle of indifference?

Amanda Askell: That’s the principle that says take the really bad outcome, the outcome where the agent was a terrible despot, then this other outcome which seems also kind of implausible that they are going to save humanity from something terrible and save millions of people.

Robert Wiblin: You just cancel them out?

Amanda Askell: Yeah, I don’t really have one reason. I don’t have more reason to think that their child is going to be a terrible despot than I do to think that they’re going to save the world and so, sure, let’s just say that these effects just get canceled out. I’m just indifferent between them.

Robert Wiblin: So, I’ve heard people in the past say that this issue of being totally unable to predict the long term consequences of your actions shows that consequentialism is wrong or it’s very problematic. I’ve even heard people say because no one even thinks about this that just shows that no one is a consequentialist. Which is kind of amusing given how much the effective altruism community stresses about this. What do you think of those arguments?

Amanda Askell: I think it’s a problem for consequentialism. One thing that’s worth noting is this is a problem that arises … Maybe this is a philosopher’s point. There’s a problem that arises in a content of making decisions rather than in a context of ranking actions. So some people are going to think about consequentialism as a theory that’s more about how you should rank actions given their actual outcomes and in that case cluelessness doesn’t arise because it’s specifically a problem about uncertainty. But you might think that it’s a problem for people who want to try to internalize a kind of consequentialist procedure, they’re really trying to work out what the best action for them to undertake is if consequentialism is true and it turns out that that’s really hard if not impossible to do.

I’m inclined to think that it is a problem if we can’t use principles to actually give kind of well defined expected values to outcomes. I suppose I’m more optimistic in the case of cluelessness that we can, given our evidence, give more precise estimates of how good the outcomes are.

Robert Wiblin: It seems more like a practical problem that an in principle problem.

Amanda Askell: Yeah-

Robert Wiblin: Even if that’s a very challenging practical problem.

Amanda Askell: Yeah, I think that’s how I … And maybe other people perceive it different but that’s how I perceive the cluelessness problem.

Robert Wiblin: I suppose you could imagine us constructing a world in the future where things are much less chaotic and much more predictable and so the cluelessness problem somewhat goes away.

Amanda Askell: Yeah and we have a lot of evidence about long term ramifications. Maybe one worry for that is going to be that even if you have a huge amount of evidence you will need something close to omniscience because you could just have random factors that huge causal ramifications. So like we said about identity, changing which children someone has is affecting the population of the entire future of humanity. You might just think that random events could have huge impacts on the outcomes of your actions.

Robert Wiblin: Yes, but I suppose at the very extreme end you could just have one non human agent that never reproduces remaining and then it would be much easier to predict the consequences of their [crosstalk 00:58:48] actions.

Amanda Askell: Yeah, we can just imagine worlds where it’s like and also there’s one agent in a box who is completely separate from the rest of the universe and so there’s no chancy behavior. And then we can maybe extrapolate from that. Yeah the amount of data we would need would be huge but in principle we could solve this problem by knowing about everything that’s going to happen, can just show the different things that we could do.

Robert Wiblin: So having mapped out this issue, do you think it’s a challenge for philosophers or is now just a challenge for social scientists and economists and things like that?

Amanda Askell: I think there’s a key challenge of figuring out whether we can actually have rational, precise credences in these kinds of cases especially if we reject this kind of principle of indifference and if so how we can make decisions under this form of uncertainty. And so for the people who think that you should just imprecise credences in this case, the key challenge is going to be giving a good decision theory for imprecise theories which is already a big challenge that philosophers are focused on and that could be something that philosophers and economists could contribute to in finding ways to demonstrate there’s irrational precise credence to have in cases like this, that’s also something that I think both philosophers and others can definitely contribute to.

Robert Wiblin: What’s an imprecise credence?

Amanda Askell: And imprecise credence is where you don’t … With credences the idea is often that we have very precise probabilities that we assign to different states of the world and this seems like an idealization, it seems like I don’t actually have real valued … I have zero point seven one four nine two three one dot dot dot dot in some given state of the world. So in imprecise credence is the value of your credence is in fact an interval between zero one one. And so maybe I think that instead of saying that I have a credence of precisely point six that this thing is going to occur, maybe I actually have a credence that’s between point five and point seven or maybe my credence is in fact the interval point five point seven. And so it just is cases where we don’t have precise credences but rather we just have intervals.

Robert Wiblin: Okay so it sounded like you were saying that if we adopt imprecise credences then we have a challenge at the decision theory end. How do these credences then interface with our decision procedure. But why would these imprecise credences really help? I guess it helps with the problem of it seeming arbitrary to give kind of a point estimate of the likelihood of kind of every possible outcome that could-

Amanda Askell: Yeah, to say that they’re equal. So the first question is what is the rational attitude to have towards these potential long term ramifications that are very positive or very negative and that are kind of unforeseen at the moment. If you answer that question with you don’t have enough … Given the lack of evidence but the fact that there might be a consistent effect in one direction than in another you should have an interval valued credence over these outcomes. At the very extreme end of interval valued credences you can have an interval that is just the entire zero one interval.

Or you may think no there is a precise credence that you have about these outcomes given your current evidence. There’s just a way of partitioning the world such that you’re like, yep, I have that specific hypothesis, I maybe even have it consciously formulated in my brain about having these positive effects on the economic situation which leads to this person being elected, which leads to this person adopting this healthcare program in this country, etc. Give that really precise state of the world I should have a very precise credence that that state of the world will be the thing that is the outcome of my action.

So the idea is you first ask what’s rational in this case and then you have to ask how does this affect our decision making and if it’s precise I think that the answer is hopefully just going to be that it’s going to massively increase the value of gaining information about these kinds of effects. If it’s imprecise then we need a decision theory that can deal with imprecise credences.

Robert Wiblin: Okay. Is it possible for this cluelessness to kind of have a funny interaction with moral uncertainty or other moral theories you might put some credence on. So you can imagine if there are moral theories saying it’s very bad if your actions have any possibility of creating a negative outcome like violating someone’s rights … If you’re only thinking about the direct effects of your actions then it seems kind of easy to avoid murdering someone or causing someone to be murdered but if you think about this spiraling uncertainty and all the chaos that your actions create and how they change the entire course of history it seems like action that you take has some possibility of causing some horrific outcome in the future and so they might all be forbidden.

Amanda Askell: Yeah one result is that you could think that this ends up in dilemmas so a theory that says you should basically never risk violating someone’s rights far into the future and then I can say every action available to be has a risk above some threshold of doing this then if your theory just says if the probability is above some threshold and it is in this case then you just shouldn’t undertake the action, that theory would presumably end up with just dilemmas given cluelessness worries.

Robert Wiblin: Which I guess on pragmatic grounds is a reason to prefer more linear theories than ones with strict prohibitions where something is like infinitely bad or very bad or just totally impermissible.

Amanda Askell: Yes-

Robert Wiblin: Because it’s twice as likely it’s twice as bad.

Amanda Askell: And I think that most theories would have that as part of them. So take a theory like a kind of moderate deontological theory, it’s not clear to me that they would actually have the same kind of problem with cluelessness that say consequentialists have because they might just say that the thing that matters is the causal effects of your actions and not necessarily things later in the causal chain that although would not have happened had you not done the thing are not in fact things that you are responsible for.

Robert Wiblin: Because another agent has touched them and now they’re responsible-

Amanda Askell: Yeah there’s an agent that’s like, well it’s not the case that if foreseeably this action will lead to Jane being born and then Jane goes onto commit a robbery that I was somehow culpable for the action of Jane’s robbery because-

Robert Wiblin: Indeed like all of her ancestors are culpable.

Amanda Askell: Exactly and so theories that deny that as presumably a lot of theories are going to just might less of a problem closeness. It might have some problem but they might not think that things like future rights violations are the responsibility of current agents. They might say yes, it is actually quite … We do want to work out this problem because we also do care about the causal impact of our actions as a lot of non consequentialists do, we just don’t think that the key thing is going to be something like rights violations that occur in the future.

Robert Wiblin: Do you see more people working on this general research question?

Amanda Askell: I think that I would classify a lot of questions in this area as … This feels to me again like an important but not necessarily urgent question. So it depends on what people would be doing otherwise I suppose.

Robert Wiblin: I suppose another way of looking at this is just being people may be trying to research what are the floater effects or the long term effects of our actions and often they end up working on existential risk or long term future projects and they’ve in some cases found things that they can work on now that they think have satisfactorily confidently positive effects in the long run but that might just be a more practical way of approaching the question.

Amanda Askell: Yeah. So there is this question of … I am not going to give a great answer to that, how useful is very theoretical research in areas that can have very real world impacts? And I think maybe I could kind of step back my earlier answer because maybe if you find a very good response to this problem it can lead to further insights that are actually themselves very useful. So things like how to quantify how valuable information about the long term effects of our actions is, is kind of difficult without an answer to this slightly more abstract seeming problem.

And so one response someone might have is something like, oh well, just do the practical work, just try and work out flow-through effects and just do all of that kind of stuff. And I’m like, yes that is really important but actually maybe if you could just generate a fairly neat solution to the abstract problem it would just give this really good grounding to all of the other practical work that occurred in this area and that could in fact be kind of helpful. So yeah, I think that sometimes this theoretical research can really great very good foundations for later practical research.

Robert Wiblin: So, given that these long term effects of our actions might be very large and also very uncertain, does that imply that this should be one of the main things that we’re researching, ’cause just the value of further information about them is so huge?

Amanda Askell: Yeah so I’ve thought before that one thing that is kind of unfortunate is that value of information is often just kind of a side consideration when it comes to thinking about how we can do good in the world. If we think that the long term effects of our actions are very large.

If we think that the long term effects of our actions are very large, it could be that finding out more about the expected long term consequences of what we do is actually an extremely valuable part of investing in intervention. And so if you think that the value of information is very high in the ethical domain, this can favor a couple of things.

One is that it can favor kind of doing more research so just trying to investigate how the world is actually going to be and what the impact of a given policy has been in the past and all of this kind of stuff, but I think another thing that it means is that investing in interventions could itself be valuable mainly because we then get information about the impacts of those interventions and so we can kind of run experiments basically, and we can try out things and see if they work.

And I’ve talked a little bit about moral value of information in the past and I think that the main thing that I kind of concluded from it was that it’s very easy to take this kind of evidence based mindset when it comes to doing the most good. We are like, let’s just take these interventions, for which I have the most evidence about what the nature of their impact is, and let’s just invest in those or you can take a kind of more expectations-based kind of approach where you say, “Well, actually, what we should do is we should run some experiments and we should try out various things and see if they work because we just don’t have a huge amount of information in this domain.”

And if you take that kind of attitude, you can end up, kind of, investing in things a bit more experimentally and I think that there’s potentially a better case to be made for that than people have appreciated and so that might be one consequence of this is just, “Hey, the ethical value of information is actually higher than we thought and maybe we should just be trying to find new ways of gaining a bunch of new information about how we can do good.

Robert Wiblin: So this is a somewhat generalized document in favor of doing things that have very uncertain outcomes as long as you can learn from them in some generalizable way?

Amanda Askell: Yeah. I think an interesting, kind of, consequence of this that is perhaps somewhat counterintuitive is that if you have two interventions and one of them is very well evidenced. We know really precisely how much good it does and we have another intervention that has a kind of plausible mechanism … because it can be terrible in expectation. So there’s a plausible mechanism for doing a bunch of good, but it has a huge range that it could do virtually nothing or it could actually be really fantastic.

So an example of the first thing might be antimalarial nets, for example, so insecticide-treated bed nets or just, there’s a lot of randomized control trials about how effective they are, but you could have another intervention on malaria that’s much more experimental and we just don’t know how effective it’s going to be, that you could actually think that, in expectation, it’s actually less effective than the first one in terms of its direct impact and yet overall, you should invest in the second one because you’ll get information about where it lies on the scale of value and that will mean you can either reinvest in it or just never invest in it again.

And so, yeah, it’s like actually, maybe you should prefer interventions with less evidential support over those with more evidential support.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. So that makes sense as long as you’re getting a good measurement of what the impact is. So this is kind of an argument in favor of, we should do a lot of science and technology and should spend a lot of money on R&D because it will have a really beneficial long-term consequences. But I guess in the case of cluelessness anyway, it seems like we might just learn basically nothing. We do a whole lot of work and then we still don’t … like we’re just as clueless at the end of the process.

Amanda Askell: Yeah. You still just haven’t touched these long-term-

Robert Wiblin: Because the problems are so fundamental and the future is so chaotic.

Amanda Askell: Yeah. You’re just like … I actually just think that I can’t really predict what the very long-term outcomes will be so I think this is a good argument for why if you can get information, especially about very long-term impacts of your actions, and that information is especially valuable, but I don’t think this is a solution to the problem of cluelessness because I think even if you can get information of that form, you would probably still have this problem because you’d be just given chaos. These long-term unforeseen consequences of my actions can still occur.

Robert Wiblin: Okay. So we’re kind of stuck with cluelessness. I mean, how would you feel about the kind of practical solution that a lot of people have gone on board with this, of just trying to reduce the probability of civilization collapsing in the hope that that is a good sign post to a good future. Is that at all satisfactory in your mind?

Amanda Askell: I think there’s, kind of, a satisfactory answer to a lot of things just because I’m like, these problems are difficult, but if you generate this space where you can reflect on them and work on them, that’s almost always a good thing so I’m sympathetic to that kind of approach to most very fundamental ethical problems. It seems very plausible to me that you should try and secure the lives of people living now and people living in the near future because you can’t solve these problems if you don’t have people who can work on them. And so, yeah, I’m sympathetic to this being the approach that people take.

Robert Wiblin: Okay. That’s somewhat reassuring.

Amanda Askell: Yeah.

Robert Wiblin: So just coming back to the value of information issue, you gave a talk about that at EA Global last year, right?

Amanda Askell: Yeah.

Robert Wiblin: So, it sounds like one of the conclusions is that you should spend more resources that you otherwise would doing things that, in a sense, not very evidenced backed, where you’re unsure what the outcome is going to be so long as you can measure and learn from it?

Amanda Askell: Yeah.

Robert Wiblin: Are there any other, kind of, key conclusions that people should take away from this value of information consideration?

Amanda Askell: I think just thinking about the different ways in which you can gain information … so I think, often, when people think about information, they really do just think about the research component and I think it’s important to know that a really good way of getting information is just by doing the thing and then getting the data to yourself.

Sometimes, the data just doesn’t exist. I think this generalizes, I mean, we haven’t talked about careers so much, but I think this is actually really important in one’s career as well, is that if you have an opportunity to simply try things, this can be a really good way of getting information about how good it is and people can get kind of paralyzed by the evidence and think that the thing to do is analyze existing evidence.

I think that one of the other conclusions that I came to with this is, think about investment as something that’s mining value of information, not just direct value so I think that was a main one.

Robert Wiblin: And I guess this is also an argument for the community as a whole, kind of, sending one person into lots of sort of different areas so that they can learn about whether it’s promising and bring that information back to the group.

Amanda Askell: Yeah, I think it’s important. I’m not saying this always overwhelms things. Maybe they’re just really important things for people to be doing and really important career tracts that are fairly narrow because immediate needs or something, outweigh this consideration, but all else being equal, I think it’s quite good for people to be trying lots of different things and seeing what the impact of them is if there’s a plausible mechanism for it being fairly high impact. So obviously, there has to be a plausible mechanism. You might just think that there are certain paths that people can go down. They’re just not likely to be super high-impact.

Robert Wiblin: Clearly, we shouldn’t send someone into everything. It’s only the things that seem promising enough, where you can learn a lot by putting someone-

Amanda Askell: Yeah. That seems right to me.

Robert Wiblin: Is there anyone who has, kind of, a good process for going through and estimating the value of information from different actions or is this still, kind of, an unsolved practical problem?

Amanda Askell: There’s a lot of research in how you should evaluate the value of information. There’s a lot of results that should make us a little bit pessimistic about this. So the thing I’d recommend that people read on it, it’s just very interesting, is stuff on multi-armed bandits, the multi-armed bandit problem. And one interesting and, kind of, relevant puzzle for practical, real world stuff is puzzles where the probabilities of success for each thing that you’re trying change.

So it’s like, imagine you’re playing a couple of multi-armed bandits, but the probability that they will … the expected payout actually changes overtime. This is an extremely difficult problem and it’s extremely difficult to know where you should explore and where you should exploit when you have problems of this form and I think a lot of the real world problems have that form, where the amount of value you get from working in a given domain might change drastically depending on ways that things in the world are going.

And so I can’t offer a huge amount of practical advice here, but I do think it would be quite possible for someone to do very applied work in this area, actually trying to assess how we should assign information values like working on a given problem, say.

Robert Wiblin: I’m planning to interview the authors of a book called Algorithms to Live By. There’s a chapter about these multi-armed bandits.

Amanda Askell: Yeah. It’s also a really great book. I recommend it.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah, it is very good. Unfortunately, I think they finished that chapter talking about how this is a very difficult, somewhat unsolved problem in computer science of what you do when the payoffs are changing over time. Maybe we’ll see if in the meantime they’ve managed to come up with any other answers.

Amanda Askell: If we just solved a potentially unsolvable problem.

Robert Wiblin: Okay. Let’s push onto a new topic. One, kind of, theme that I’ve noticed to some of the things you’ve written online is, kind of, what seems to me like an attempt to, kind of, synthesize the views or arguments that are often associated with social justice activism, with, kind of, a more rational or analytical, philosophical style.

Amanda Askell: Yep.

Robert Wiblin: Is that something that you’re consciously trying to do?

Amanda Askell: I think it’s party just that I often agree with many of the arguments or conclusions of people who are advocating for greater social justice and I see a lot of common themes between that and people who are effective altruists. This idea of expanding your, kind of, moral circle beyond people who are just like you and in your, kind of, local area, but rather to lots of different people in society and looking back at the, kind of, history and the effects that those people have underwent and trying to basically improve the lives of as many people as possible. And I think that, in some ways, this can get, kind of, … there are really good arguments for many of the positions that I think social justice advocates are putting forward.

And so I always just want to, kind of, make those arguments because I think, sometimes, they can be caricatured or bad forms of them can end up being released on the internet and suddenly everyone thinks that that’s … I don’t want it to be the case that people start to think, “Oh, the only defense of these, kind of, social justice movements are these arguments that I disagree with.” I’m like, “No. There are actually really good arguments there and so we should search for those and look at the merits of the best arguments and not merely dismiss things because we don’t like the way that it’s put”.

Robert Wiblin: So it’s a bit surprising that there’s so many, kind of, conclusions that you, kind of, agree with that are often being justified on bad grounds, but … How is it that the conclusions are good if you think that the typical arguments being made are not good? Is this an example of moral convergence with different theories or when thought through properly, kind of, reach the same ideas?

Amanda Askell: I think that there are actually good arguments. So it’s hard to talk about it without specifics, but something that I am really interested in is some issues in things like criminal justice reform and I think that the arguments in favor of that, that are quite effective, are ones that look at the history of, say, the criminal justice system in the U.S.. Who it currently affects? The fact that it affects minorities really strongly even when there’s, kind of, parity of crimes being committed.

And so, those arguments are out there and I think that what people sometimes do, is they don’t … or maybe they disagree with a conclusion or they just see a bad form of the argument made somewhere and don’t think, well, actually, maybe there’s a really good case to be made for this or maybe there’s a really good case for us to be a bit humble about what we think in these areas because we’ve just come out of really, quite terrible periods in history and we should maybe think that our society isn’t set up in this really great way for everyone, seems pretty plausible to me.

And instead, they’re just, kind of, seeing an argument they don’t like made by someone on Twitter or something and they’re taking that to be representative of all of the work that’s gone into this, when, actually, I think that the work that’s gone into this from historians and philosophers and various other people is often way better than the thing that you’re reading on Twitter.

So it’s, kind of like, remember that there’s actually really good to … and I think there really is quite robust stuff here and that we shouldn’t just, kind of, dismiss things because we don’t like the way that one person puts it. So I feel very strongly about that, I guess.

Robert Wiblin: So, to make it more concrete and, I guess, possibly, more provocative to some group that I’m not sure which one yet, are there any, kind of, specific debates around social justice activism that you think deserve a steel man philosophical defense that haven’t been defended as well as you’d like?

Amanda Askell: So, I think, maybe I want to focus on a, kind of, reframing of some issues that I hope that people can agree on. So sometimes I think that it’s really unfortunate that policies that could potentially be good and that we’re really just trying out … for example, positive discrimination. Positive discrimination is quite controversial, I think. I see that more as a, kind of, social experiment, something that we should try out for a long time and see if it works and see if it makes people’s lives better and if it does, then that’s great and if it doesn’t, then we’ve performed an experiment and we found out that this wasn’t the way to actually improve people’s lives.

And so sometimes, I think that you can defend a lot of policies and you can find convergence on policies if you explain to people that this is an area where it’s important for us to just try various things and to get the information on whether they work. And sometimes I think people are doing the thing that we talked about earlier, where they’re looking for … that’s like, “I must have just established that this intervention works really well before I try it,” whereas, my attitude is like, “Hey, here’s a defense of these policies.

We should just try them for a fairly long time and see if the long-term ramifications of them are good because that’s what we’re trying to improve. Isn’t just the life of this one person right now, but rather to try and make society more equitable and function better for everyone. Yeah. I think that’s a steel man of specific policies that are controversial. Yeah, I have lots of very pro, kind of, social justice views that I think are very steel man-able, I guess.

Robert Wiblin: I guess, with experimentation, the usual approach is to experiment on a smaller scale and then increase the scale as the evidence base gets better. Why do you think we should experiment with a little action on a broader scale first or for such a long time?

Amanda Askell: Yeah, so I’m not sure about the broad scale versus … with a bunch on interventions, you probably want to experiment with them. There are ethical issues with experimentation, if you think that it’s likely that this policy will succeed because then you’re harming the people in the areas where you’re not performing the experiment. I’m more in favor of just trying to gather more information, but I kind of understand that people might have worries about that kind of thing.

I think that long-term, the structures that we have in society now, took a long time to build up and the idea that our goals should just be to, kind of, in the short-term, just change the lives of people and everything will be fine, seems implausible to me. Rather, I think that we want to, kind of, slowly make adjustments to society that will make everyone better off and that will involve doing things that are better in the long-term.

I am not certain that we should just be doing broad scale things rather than experimenting and seeing what works. That could be really good. Maybe you have one university that tries one thing to make their classes more inclusive and then you have another university that tries another thing and then you get more information about which of those things was better. That seems quite good to me, but I also do think it’s good to take this long-term attitude towards these things and be like, “We want to change society incrementally in the long run and not just in the immediate next two years or something like that.”

Robert Wiblin: So, it seems to me like there’s often kind of a tension between people who are really analytical, philosophical style of reasoning and social justice activists. Do you think this is indicative of really fundamental disagreements or is it more a matter of how they speak and how they like to communicate and perhaps things being lost in translation?

Amanda Askell: I mean, I tend to think that it’s more the latter, but I also have … I’ve been in this and I know other people who are similar where I have never been … I didn’t go to college in the U.S., for example, and a lot of people talk about the specific U.S. college experience that I just didn’t have. So all of my exposure to things like feminism and social justice, came really vie academics and people who were making extremely reasonable and sound arguments that I agreed with … obviously, there’s lots of reasonable disagreement on all of these issues, but I never encountered something that I thought was anything that was inconsistent with just analytical, kind of, careful arguing styles … or at least for the most part, I didn’t.

And so far as there’s tension being created in the, kind of, public discourse, I suspect that it’s not over … it’s not because one side has logic and reason on its side. I think there’s just a cluster of really reasonable disagreements here. And it could also just be that people are just dividing into political tribes and that’s, I think, a very damaging thing that can happen and that could also just be the source of it here.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah, how impactful do you think it would be for someone to try to do a rational synthesis of social justice ideas or try to carve out, kind of, conclusions that are appealing to one side, using reasoning that’s appealing to the other side or to help people understand one another. I guess, it seems like that would be quite a personally challenging thing to do because you’d be attacked by all kinds of people whenever you touch these issues.

Amanda Askell: I don’t know how unfair it is to academic work in this area because I have looked into this a little bit and you have readers on some of these issues. So there are historians or people who look at the history of U.S. policy, like historians of U.S. housing policy, for example, can give you a lot of information about why you see very entrenched divisions in housing in the U.S. now, and that work is good and accessible. I do think that there could be … maybe it would be good to have more work that is engaging directly with the public on some of this stuff and I think we’re seeing more of that.

I’ve definitely seen a couple books come out recently, which were targeted at a general audience and were just trying to slowly go through all the arguments in favor of, say, … there was a recent book on misogyny and I read through some of it (‘Down Girl’ by Kate Manne). And it was like, yeah, this is just reasoned arguments about the nature of misogyny that aimed at a general audience and I think does a decent job of communicating these ideas in a way that … not everyone is going to be sympathetic to it, but at least it’s not obscure. It’s very standard, kind of, analytical style, I guess.

Robert Wiblin: So, when I mentioned on Facebook that I was going to be interviewing you, someone asked the question, whether you think utilitarianism is compatible with social justice causes and to what degree do you think they’re actually intentioned?

Amanda Askell: Yeah, so I think that one thing that happens a lot with people who think that utilitarianism is correct, is that you can end up having to prioritize causes based on how much harm you think that they’re causing. And so this can mean that you have a kind of ranking of things in terms of badness, like the things that you want to work on. So it took me a long … When I was younger, I became vegan. I was very interested in animal ethics.

I think one of the first books I read in ethics was Peter Singer’s Animal Liberation and then when I heard about effective altruism, I was really convinced by these arguments that global poverty was very important. And that’s actually where I’ve put most of my money, for example, and then slowly, I was, kind of, reluctantly convinced that these issues, like reducing existential risks were actually really important.

And I think that’s a good process to go through. There’s a sense, in which, if you reach these unusual conclusions about what’s most important, non-reluctantly, I kind of trust them less. I came to that conclusion kicking and screaming and trying to find every argument against it, but it can make it look like you think that the other stuff is less important. So if you come to the conclusion, “Oh, I should be working on reducing existential risk, so I don’t work on global poverty and I don’t work on issues that affect animals,” that you somehow think that those things are not important.

And I think the same can be true of social justice causes and I think it’s important to emphasize that that’s not the case. I think criminal justice reform in the U.S. is an incredibly important topic and one that people should be tackling. I think issues of improving the lives of women is incredibly … both within the U.S. and around the world is incredibly important and one that people should be tackling and so I don’t think that there is a tension fundamentally because I think that often, people working on social justice issues have the, kind of, the core thing that effective altruism or utilitarians, kind of, agree with.

Namely, they’re trying to expand their moral circle and they’re trying to benefit the lives of people and the tension comes at the level of what they prioritize and I think this is both, in terms of the causes that they end up investing in and also things like whether think that systematic versus incremental change is important. So I see those as being two of the, kind of, tensions.

I think utilitarians are often more inclined to favor incremental change rather than sweeping changing if they think that it’s implausible that we can actually get sweeping change, whereas a lot of people are more … I think a lot of social justice movement work is focused on, not solely on systematic change, but more so on systematic change and so I think it’s sort of unfortunate because I would rather have this attitude of, there’s a cluster of things that are super important. I want people working on those things and just because I’m having to do this weird ranking and then working on things that I think are most important, it doesn’t in any way diminish the ethical work that other people are doing.

Robert Wiblin: I guess, imagining that there’s kind of two groups: social justice activists and people who are skeptical of social justice activism. What would be your biggest criticism of each group? How would you like to see them change and improve?

Amanda Askell: So, I suspect that I would like more of a, kind of, prioritization attitude in social justice activism and it’s not to say it’s not there, but prioritization is not a, kind of, common tool that’s wielded in most places, I guess, and so it would be nice to see … and also maybe a broadening of the scope of issues that people work on and that’s sort of happening. I think you’re seeing people care a little bit, like immigration issues, for example, more than in the past and I hope that we’ll also see this with caring about global poverty issues as a, kind of, social justice concern.

And so I think a mix of really trying to target the things that will have the most impact would be really good and also, yeah, broadening the issues that people consider, which is happening and I think it’s going to be good thing. I suspect, more based on the interaction with other people or testimony from other people than any personal interaction I’ve had, that the thing that people mainly find off-putting about social justice activists is the methods of engagement of some of them.

And maybe some people feel, kind of, attacked when they just don’t understand these issues or they want to get to know them and they feel like they make mistakes and then they get, kind of, eviscerated and they’re like, “Well, I just don’t know anything about this issue and I don’t feel like I’m being engaged with fairly,” and if that’s the case, it’s probably not a good way to have a dialogue with people. It’s good to be like, “Look, some people just won’t understand this stuff or have encountered it and it’s important to be kind and considerate while they’re learning about it and if we aren’t, that’s just bad for discourse.

And I think from the, kind of, more … people who are anti-social justice activism, I think it’s a mix of … what I would want to see more of is a combination of epistemic humility and probably historical research. So in some ways, for me, a large influence was simply looking at the history … how recent the history of a lot of this stuff is. We just had an incredibly unequal society and we’ve had laws enforcing really unacceptably, unequal ways up until … like school segregation was happening until way more recently than I thought.

And when I looked into school segregation in the U.S. and I was … there were schools that were fighting this really not that long ago. And so I think that having a, kind of, more historically informed attitude towards why we should, kind of, expect society to be, kind of, unequal to be good and taking that historical information and using it to be like, “I’m going to be a bit humble about this issue so I’m not going to assume by default that everything is equal. Instead, I’m going to assume that it is just very likely that people are, kind of, doing worse than they otherwise would if we had just had a kind of fair society.

So, yeah, historical research and a little bit of epistemic humility is probably the other good thing.

Robert Wiblin: So, how do you think the quality of discourse between those groups could be improved the most so that they can actually gain some kind of mutual understanding and, perhaps, even be able to work together on solving some problems that they both accept?

Amanda Askell: Yeah, so I think that one phenomenon that I’ve seen happening sometimes in these debates is that people will … they’ll have a controversial view that they want to, kind of, put forward or at least have in the eyes of their reader, kind of, supported, but they won’t want to take ownership over the controversial view and so they’ll assert something that seems to, kind of, strongly implicate the controversial view. So an example of this might be saying something like, “Oh, most of the wage gap between men and women can be explained by women’s choices.”

And so someone might post something about a study that just talks about the fact that women take more time off work to do childcare, explains the different in income. And this can seem to imply that there’s no problem basically. So there’s no bias against women in the workplace, nor is there any need for systematic change of the way that we do childcare or the nature of taking time off for maternity leave or anything.

And they might not want to assert, there is no problem and there is no bias against women in the workplace and there is no need for change, but that’s often, kind of, implicated if you don’t cancel it, if you don’t say, “I’m not saying that this explains everything or that there’s no need for change, but we should note that some of this is explained by this other phenomenon.” And so if you express your values and you show that you really care about women and that this is just a way of finding out the best way to improve the lives of women, I think a lot of people are actually really sympathetic to that kind of claim.

So if I were to say, “Oh, it turns out that this is the thing that’s causing women to earn less, so we should be focusing on that thing and how to improve it and what we can do here.” That’s just a very different thing than just asserting the fact with the full awareness that what people are going to pick up on is the standard, kind of, cluster views that people who assert those facts have. And so I think that this is quite damaging because you want to just engage with people at the level of their actual views and to be able to criticize those views.

And doing this, kind of, thing where you implicate a controversial view without asserting it and then if someone says, “I don’t believe in the controversial view,” you say, “I never said that. I just said this fact.” It just means that people can’t actually engage at the right level with one another. And so, I guess, when I see that kind of thing happening, it makes me sad because it just doesn’t lead to, kind of, good discourse.

And so I think that one thing that I … It’s maybe a kind of obscure thing that I want to see happen a bit more, is people kind of taking ownership over the things that are implicated by what they say and either canceling it by saying I don’t actually think that thing or just embracing it and saying the thing that I think is this more controversial thing and I think it’s supported by this piece of evidence that I just gave you. Because it just feels like a more honest discourse then.

I know what someone’s view is and I like to think I try to do that. I try to strongly express my values before I state something and if I’m aware that the thing that I could say could be interpreted in a way that is not consistent with my values, then I try and eliminate that interpretation or try to clarify it later. If I say something and people are like, oh, it sounds like you’re saying that this terrible thing. Then, I’ll be like, “Oh, I totally didn’t mean that. I see how you thought I was saying that.

It seems like an important part of good discourse to me. It seems like an important part of honest discourse and so I would want to see people not doing, kind of, yeah, this discourse via implication or something.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah, because this is consistent with like … one way of shortening that advice is, kind of, the more controversial, the more you’re talking about a hot button issue, the more you have to be extremely careful to be clear about exactly what you are saying and what you are not saying?

Amanda Askell: Yeah. I think that’s right. I-

Robert Wiblin: And I guess, also, show concern for the other side and they’re interest. So you can completely disagree about … you might share more values and more goals than might be immediately apparent.

Amanda Askell: Yeah, yeah. And strongly share your values. In some ways, the thing that I don’t like is when I think someone’s values are bad. So if I think that someone genuinely cares about all of the people that I care about and they just think that there’s a different way of helping them, our disagreement is in many way, much less strong, right? That’s a productive disagreement to have where they’re like, “Look, I really want these people to flourish, but this policy just isn’t helping them right now. So I want the poor to flourish, but this taxation policy is actually harming them and so I don’t agree with this taxation policy.”

That’s a much better discourse to have than having a discourse with someone where you’re like, “I’m not even sure you care about these people.” So I think both being very clear about your views, but also being really clear about your values can be very helpful here.

Robert Wiblin: That reminds me of this blog post you wrote a while back, which I really loved about vegetarianism and abortion and, I guess, trying to get good moral discourse between groups with actually different values, I guess, in this case. Do you want to explain the argument that you were making then?

Amanda Askell: Yes. The argument was basically that we often seem to betray a kind of complete lack of what I call moral empathy, where moral empathy is trying to get inside the mindset of someone who expresses views that we disagree with and see that from their point of view, what they’re talking about is a moral issue and not merely a preference. The first example is vegetarianism where you’ll sometimes see people basically get very annoyed, say, with their vegetarian family member because the person doesn’t want to eat meat at a family gathering or something like that. I think the example I give is, this makes sense if you just think of vegetarianism like a preference.

It’s just like, “Oh, they’re being awkward. They just have this random preference that they want me to try and accommodate.” It’s much less acceptable if you think of it as a moral view. You see this where people are a bit more respectful of religious views. So if someone eats halal, I think that it would be seen as unacceptable to … people wouldn’t have the same attitude of, oh, how annoying and how terrible of them, but I also think that this is … So, I wanted to use a couple of examples in this post of this phenomenon.