Mpox and H5N1: assessing the situation

The idea this week: mpox and a bird flu virus are testing our pandemic readiness.

Would we be ready for another pandemic?

It became clear in 2020 that the world hadn’t done enough to prepare for the rapid, global spread of a particularly deadly virus. Four years on, our resilience faces new tests.

Two viruses have raised global concerns:

- Mpox — formerly known as monkeypox — has been declared a public health emergency of international concern by the World Health Organisation based on its spread from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) to nearby countries.

- H5N1 — a strain of bird flu — has been spreading among animals in the United States and elsewhere, with a small number of infections reported in humans.

Here’s what we know about each:

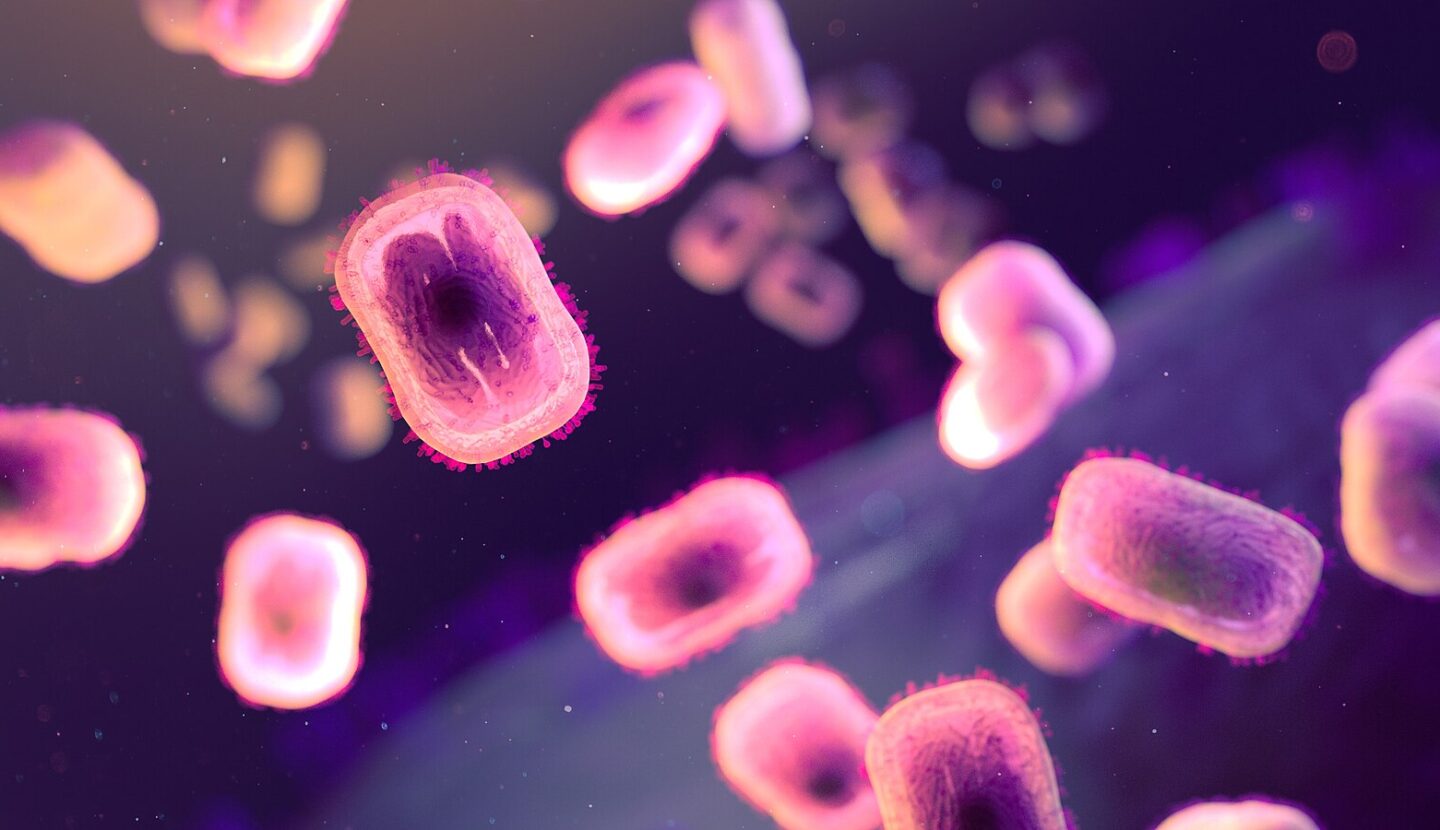

Mpox

Mpox drew international attention in 2022 when it started spreading globally, including in the US and the UK. During that outbreak, around 95,000 cases and about 180 deaths were reported. That wave largely subsided in much of the world, in part due to targeted vaccination campaigns, but the spread of another strain of the virus has sharply accelerated in Central Africa.

The strain driving the current outbreak may be significantly more deadly. Around 22,000 suspected mpox infections and more than 1,200 deaths have been reported in the DRC since January 2023..

These numbers may be artificially low because of insufficient tracking. The virus has spread to several African countries that haven’t previously seen any infections, and children appear to be particularly at risk.

The Africa CDC criticised the international community for largely “ignoring” the continent’s spike in cases after infections began to decline elsewhere.

“We urge our international partners to seize this moment to act differently and collaborate closely with Africa CDC to provide the necessary support to our Member States,” said Africa CDC Director General Dr. Jean Kaseya.

Thankfully, unlike with COVID, we don’t have to wait for a vaccine to be invented — it already exists. The challenge is producing enough of it in time and getting it where it’s needed most.

The US CDC says it is supporting countries in Central Africa with disease surveillance, testing capacity, infection prevention and control, and a vaccination strategy for the DRC.

For more on the mpox outbreak, read this report from Sentinel, a team working to forecast and prevent the largest-scale pandemics.

H5N1

Meanwhile, the H5N1 bird flu virus is currently a less dire threat, but it still raises serious concerns. It is spreading in the US among wild birds as well as farmed chickens and cows. Thirteen people in close contact with infected animals have reportedly caught the virus, according to the CDC, but it is not believed to be spreading between humans at the moment.

The US CDC says that the risk to humans generally remains low, and isn’t recommending the public take any specific measures right now. But a recent report concluded that the virus has “moderate” pandemic potential, similar to other strains of bird flu. (More details.)

In 2023, researcher Juan Cambeiro wrote a report with the Institute for Progress finding that though the risk of an H5N1 pandemic was low, it would likely be more severe than COVID-19 if it emerged.

While the CDC is monitoring the spread of the virus, some experts have warned that we’re not testing enough for new cases of H5N1. That could mean we’d lose precious time to mitigate a larger outbreak.

“I am very confident there are more people being infected than we know about,” said University of Texas Medical Branch researcher Gregory Gray in a recent article for KFF Health News. “Largely, that’s because our surveillance has been so poor.”

But there are some promising signs in the response:

- The US Department of Health and Human Services has awarded Moderna $176 million to develop an mRNA vaccine for an H5 flu variant, which officials think would protect against H5N1. (More details about existing vaccines.)

- Researchers at WastewaterSCAN have shared data tracking the geographic spread of the virus.

- The World Health Organisation has launched a project aimed at securing access to future H5N1 mRNA vaccines for low- and middle-income countries.

Overall, the risk that H5N1 will become a pandemic soon is probably low, though it’s hard to be confident:

- One prediction site, Metaculus, puts the chance of any reported human-to-human transmission of the virus by the end of the year at only 6%

- On Polymarket, the odds of the World Health Organisation declaring a bird flu pandemic this year have been around 11% recently, though with significant variation over time.

- Manifold — another prediction platform — rated the chance that the World Health Organisation declares an H5N1 pandemic by 2030 to be about 50% at the time of this writing.

What we can do

Given how bad pandemics are, we should be taking even a low risk very seriously. The Institute for Progress article estimated that, even with a 4% chance of a virus causing a pandemic as bad or worse than COVID-19, “the expected cost in terms of potential harms to the U.S. is at least $640 billion.” For comparison, the US spent $832 billion on Medicare in 2023, a program that covers 66 million Americans.

The current outbreaks of mpox and H5N1 will likely be tamed without having major global impacts. But new threats will emerge, and humanity will be much better off if we have a well-honed, consistently applied playbook for controlling these pathogens before they cause a crisis.

Some things we should be doing:

- Ensuring we have robust testing regimes when new outbreaks arise

- Routinely ramping up vaccine productions for emerging pathogens, perhaps with advance market commitments, even if the chance we’ll need them in any given case is low

- Taking more active steps to reduce the pandemic risk we face from zoonotic spillover, potential lab accidents, and intentional biological attacks

We have a lot more details about this problem in our article about preparing for the deadliest pandemics and our content on careers reducing biorisks. If you’re a good fit for this kind of work, it could be your best way to have a positive impact.

This blog post was first released to our newsletter subscribers.

Join over 500,000 newsletter subscribers who get content like this in their inboxes weekly — and we’ll also mail you a free book!

Learn more:

- The next Black Death (or worse)

- Rachel Glennerster on how “market shaping” could help solve climate change, pandemics, and other global problems

- Kevin Esvelt on cults that want to kill everyone, stealth vs wildfire pandemics, and how he felt inventing gene drives