Part 1: We reviewed over 60 studies about what makes for a dream job. Here’s what we found.

We all want to find a dream job that’s enjoyable and meaningful, but what does that actually mean?

Some people imagine that the answer involves discovering their passion through a flash of insight, while others think that the key elements of their dream job are that it be easy and highly paid.

We’ve reviewed three decades of research into the causes of a satisfying life and career, drawing on over 60 studies, and we didn’t find much evidence for these views.

Instead, we found six key ingredients of a dream job. They don’t include income, and they aren’t as simple as “following your passion.”

In fact, following your passion can lead you astray. Steve Jobs was passionate about Zen Buddhism before entering technology. Maya Angelou worked as a calypso dancer before she became a celebrated poet and civil rights activist.

Rather, you can develop passion by doing work that you find enjoyable and meaningful. The key is to get good at something that helps other people.

Watch this video or read the full article (20 minutes). If you just want the raw research, see the evidence review.

The bottom line

To find a dream job, look for:

- Work you’re good at.

- Work that helps others.

- Supportive conditions: engaging work that lets you enter a state of flow, supportive colleagues, lack of major negatives like unfair pay, and work that fits your personal life.

Table of Contents

Where we go wrong

The usual way people try to work out their dream job is to imagine different jobs and think about how satisfying they seem. Or they think about times they’ve felt fulfilled in the past and self-reflect about what matters most to them.

If this were a normal career guide, we’d start by getting you to write out a list of what you most want from a job, like “working outdoors” and “working with ambitious people.” The bestselling career advice book of all time, What Color is Your Parachute, recommends exactly this. The hope is that, deep down, people know what they really want.

However, research shows that although self-reflection is useful, it only goes so far.

You can probably think of times in your own life when you were excited about a holiday or party — but when it actually happened, it was just OK. In the last few decades, research has shown that this is common: we’re not always great at predicting what will make us most happy, and we don’t realise how bad we are. You can find an overview of some of this research in the footnotes.1

It turns out we’re even bad at remembering how satisfying different experiences were. One well-established mistake is that we often judge experiences mainly by their endings:2 if you missed your flight on the last day of an enjoyable holiday, you’ll probably remember the holiday as bad.

The fact that we often judge the pleasure of an experience by its ending can cause us to make some curious choices.

Prof Dan Gilbert, Stumbling on Happiness

This means we can’t just trust our intuitions; we need a more systematic way of working out which job is best for us.

The same research that proves how bad we are at self-reflection can help us make more informed choices. We now have three decades of research into positive psychology — the science of happiness — as well as decades of research into motivation and job satisfaction. We’ll summarise the main lessons of this research and explain what it means for finding a fulfilling job.

Two overrated goals for a fulfilling career

People often imagine that a dream job is well paid and easy.

In 2015, one of the leading job rankings in the US, provided by CareerCast, rated jobs on the following criteria:3

- Is it highly paid?

- Is it going to be highly paid in the future?

- Is it stressful?

- Is the working environment unpleasant?

Based on this, the best job was: actuary.4 That is, someone who uses statistics to measure and manage risks, often in the insurance industry.

It’s true that actuaries are more satisfied with their jobs than average, but they’re not among the most satisfied.5 Only 36% say their work is meaningful,6 so being an actuary isn’t a particularly fulfilling career.

So the CareerCast list isn’t capturing everything. In fact, the evidence suggests that money and avoiding stress aren’t that important.

Money makes you happier, but only a little

It’s a cliche that “you can’t buy happiness,” but at the same time, better pay is people’s top priority when looking for new jobs.7 Moreover, when people are asked what would most improve the quality of their lives, the most common answer is more money.8

What’s going on here? Which side is right?

A lot of the research on this question is remarkably low quality. But several major studies in economics offer more clarity. We reviewed the best studies available, and the truth turns out to lie in the middle: money does make you happy, but only a little.

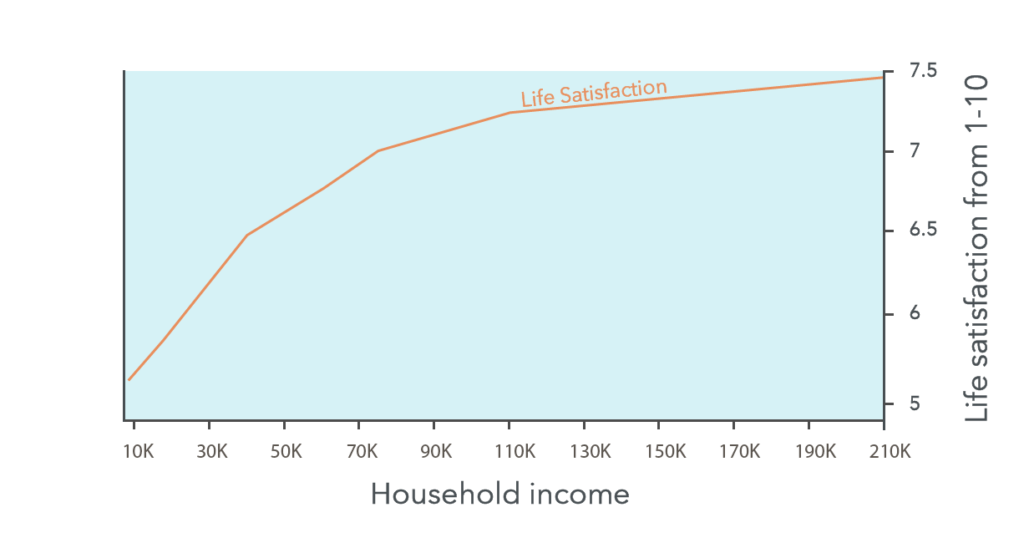

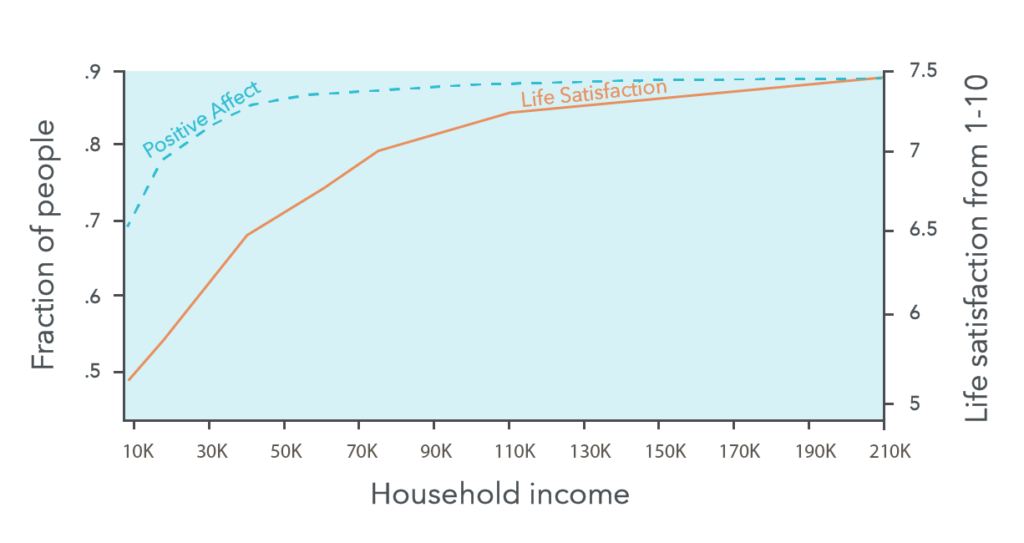

For instance, here are the findings from a huge survey in the United States in 2010:

People were asked to rate how satisfied they were with their lives on a scale from 1 to 10. The result is shown on the right, while the bottom shows their household income.

You can see that going from a (pre-tax) income of $40,000 to $80,000 was only associated with an increase in life satisfaction from about 6.5 to 7 out of 10. That’s a lot of extra income for a small increase.

This is hardly surprising — we all know people who’ve gone into high-earning jobs and ended up miserable.

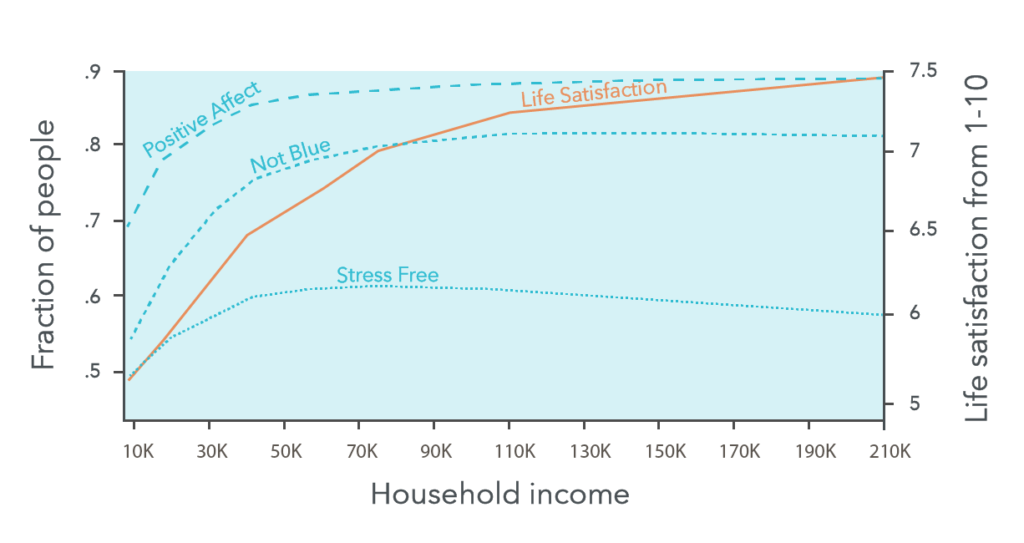

But this result may be too optimistic. If we look at day-to-day happiness, income seems even less important. “Positive affect” is whether people reported feeling happy yesterday. The left axis of the chart below shows the fraction of people who reported “yes.” This line goes flat around $50,000, showing that beyond this point, income had no relationship with day-to-day happiness in this survey.

The picture is similar if we look at the fraction who reported being “not blue” or “stress free” yesterday.

These lines are completely flat by $90,000. Beyond this point, income had no relationship with how happy, sad, or stressed people felt.

We think there’s a good chance this result is an error, and day-to-day happiness does continue to increase with income, at least a little bit.

More recent data supports the idea that day-to-day happiness increases with income, even beyond $90,000 a year — though it found that day-to-day happiness increases more slowly than life satisfaction.9

In 2023, Kahneman looked again at his old data, and noticed that a high proportion of people reported (nearly) maximum happiness scores. This could have caused a flattening of the curve despite actual increases in happiness.10

Everything we’ve covered above is only about the correlation between income and happiness. But the relationship might be caused by a third factor. For example, being healthy could both make you happier and allow you to earn more. If this is true, then the effect of earning extra money will be even weaker than the correlations above suggest.

Finally, $90,000 of household income is equivalent to an individual income of only $48,000 if you don’t have kids.11

To customise these levels for yourself, make the following adjustments (all pre-tax):

- The $48,000 figure was for 2009. Due to inflation, it’s more like $68,000 in 2023.

- Add $25,000 per dependent who does not work that you fully support.

- Add 50% if you live in an expensive city (e.g. New York or San Francisco), or subtract 30% if you live somewhere cheap (e.g. rural Tennessee). You can find cost-of-living calculations online, like this one.

- Add more if you’re especially motivated by money (or subtract some if you have frugal tastes).

- Add 15% in order to be able to save for retirement (or however much you personally need to save in order to maintain the standard of living you want).

As of 2023, the average college graduate in the United States can expect to make about $77,000 per year over their working life, while the average Ivy League graduate earns over $120,000.12 The upshot is that if you’re a college graduate in the US (or a similar country), then you’ll likely end up well into the range where more income has little effect on your happiness.

(Read much more about this evidence.)

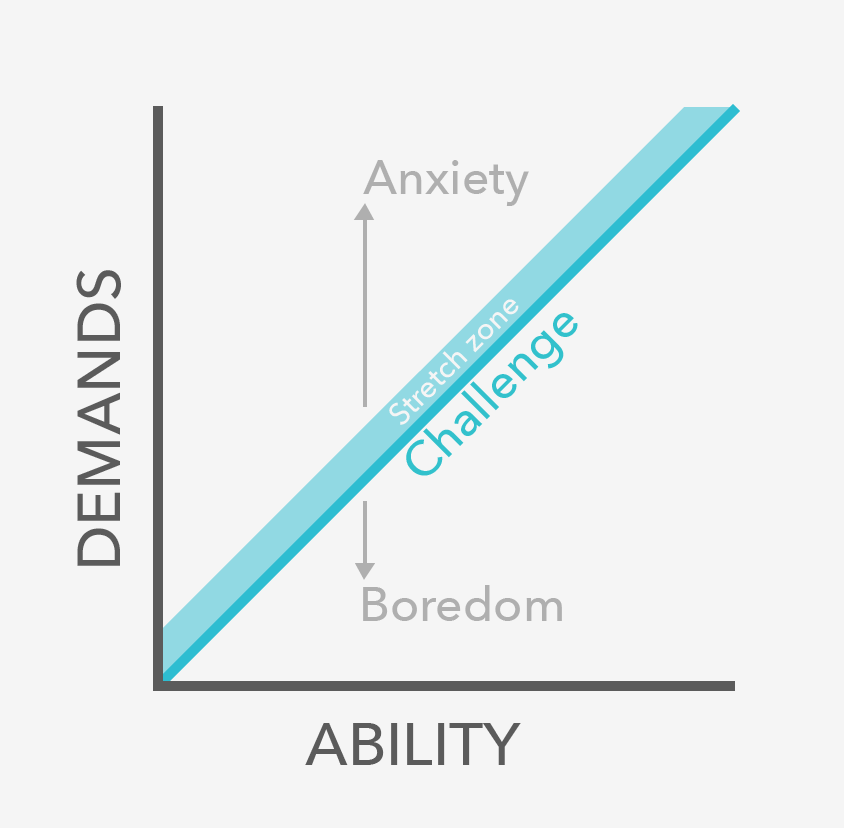

Don’t aim for low stress

Many people tell us they want to find a job that’s not too stressful. And it’s true that in the past, doctors and psychologists believed that stress was always bad. However, we did a survey of the modern literature on stress, and today, the picture is a bit more complicated.

One puzzle is that studies of high-ranking government and military leaders found they had lower levels of stress hormones and less anxiety, despite sleeping fewer hours, managing more people, and having higher occupational demands. One widely supported explanation is that having a greater sense of control (by setting their own schedules and determining how to tackle the challenges they face) protects them against the demands of the position.

There are other ways that a demanding job can be good or bad depending on context:

| Variable | Good (or neutral) | Bad | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of stress | Intensity of demands | Challenging but achievable | Mismatched with ability (either too high or too low) |

| Duration | Short-term | On-going | |

| Context | Control | High control and autonomy | Low control and autonomy |

| Power | High power | Low power | |

| Social Support | Good social support | Social isolation | |

| How to cope | Mindset | Reframe demands as opportunities, stress as useful | View demands as threats, stress as harmful to health |

| Altruism | Performing altruistic acts | Focusing on yourself | |

This means the picture looks more like the following graph. Having a very undemanding job is bad — that’s boring. Having demands that exceed your abilities is bad too: they cause harmful stress. The sweet spot is where the demands placed on you match your abilities — that’s a fulfilling challenge.

Instead of seeking to avoid stress, seek out a supportive context and meaningful work, and then challenge yourself.

(See our evidence survey on stress for more information.)

What should you aim for in a dream job?

We’ve applied the research on positive psychology about what makes for a fulfilling life and combined it with research on job satisfaction to come up with six key ingredients of a dream job. (If you want to dig into the evidence in more depth, see our evidence review.)

These are the six ingredients.

1. Work that’s engaging

What really matters is not your salary, status, type of company, and so on, but rather what you do day by day and hour by hour.

Engaging work is work that draws you in, holds your attention, and gives you a sense of flow. It’s the reason an hour spent editing a spreadsheet can feel like pure drudgery, while an hour spent playing a computer game can feel like no time at all: computer games are designed to be as engaging as possible.

What makes the difference? Why are computer games engaging while office admin isn’t? Researchers have identified four factors:

- The freedom to decide how to perform your work.

- Clear tasks, with a clearly defined start and end.

- Variety in the types of tasks.

- Feedback, so you know how well you’re doing.

Each of these factors has been shown to correlate with job satisfaction in a major meta-analysis (r=0.4), and they are widely thought by experts to be the most empirically verified predictors of job satisfaction.

That said, playing computer games is not the key to a fulfilling life (and not just because you won’t get paid). That’s because you also need…

2. Work that helps others

The following jobs have the four ingredients of engaging work that we discussed. But when asked, over three quarters of people doing them say they don’t find them meaningful:13

- Revenue analyst

- Fashion designer

- TV newscast director

These jobs, however, are seen as meaningful by almost everyone who does them:

- Fire service officer

- Nurse / midwife

- Neurosurgeon

The key difference is that the second set of jobs seem to help other people. That’s why they’re meaningful, and that’s why helping others is our second factor.

There’s a growing body of evidence that helping others is a key ingredient for life satisfaction. People who volunteer are less depressed and healthier. A meta-analysis of 23 randomised studies showed that performing acts of kindness makes the giver happier.14 And a global survey found that people who donate to charity are as satisfied with their lives as those who earn twice as much.15

Helping others isn’t the only route to a meaningful career, but it’s widely accepted by researchers that it’s one of the most powerful.

(We explore jobs that really help people in the next part of the guide, including jobs that help indirectly as well as directly.)

3. Work you’re good at

Being good at your work gives you a sense of achievement, a key ingredient of life satisfaction discovered by positive psychology.

It also gives you the power to negotiate for the other components of a fulfilling job — such as the ability to work on meaningful projects, undertake engaging tasks, and earn fair pay. If people value your contribution, you can ask for these conditions in return.

For both reasons, skill ultimately trumps interest. Even if you love art, if you pursue it as a career but aren’t good at it, you’ll end up doing boring graphic design for companies you don’t care about.

That’s not to say you should only do work you’re already good at — but you do want the potential to get good at it.

(We have a whole article later in the guide about working out what you’re good at, and another on how to invest in your skills.)

4. Work with supportive colleagues

Obviously, if you hate your colleagues and work for a boss from hell, you’re not going to be satisfied.

Since good relationships are such an important part of having a fulfilling life, it’s important to be able to become friends with at least a couple of people at work. And this probably means working with at least a few people who are similar to you.

However, you don’t need to become friends with everyone, or even like all of your colleagues. Research shows that perhaps the most important factor is whether you can get help from your colleagues when you run into problems. A major meta-analysis found “social support” was among the top predictors of job satisfaction (r=0.56).

People who are disagreeable and different from you can be the people who’ll give you the most useful feedback, provided they care about your interests. This is because they’ll tell it like it is, and have a different perspective. Professor Adam Grant calls these people “disagreeable givers.”

When we think of dream jobs, we usually focus on the role. But who you work with is almost as important. A bad boss can ruin a dream position, while even boring work can be fun if done with a friend. So when selecting a job, will you be able to make friends with some people in the workplace? And more importantly, does the culture of the workplace make it easy to get help, get feedback, and work together?

5. Work that doesn’t have major negatives

To be satisfied, everything above is important. But you also need the absence of things that make work unpleasant. All of the following tend to be linked to job dissatisfaction.

- A long commute, especially if it’s over an hour by bus.

- Very long hours.

- Pay you feel is unfair.

- Job insecurity.

Although these sound obvious, people often overlook them. The negative consequences of a long commute can be enough to outweigh many other positive factors.

6. Work that fits with the rest of your life

You don’t have to get all the ingredients of a fulfilling life from your job. It’s possible to find a job that pays the bills and excel in a side project; or to find a sense of meaning through philanthropy or volunteering; or to build great relationships outside of work.

We’ve advised plenty of people who have done this. There are famous examples too — Einstein had his most productive year in 1905, while working as a clerk at a patent office.

So this last factor is a reminder to consider how your career fits with the rest of your life.16

Before we move on, here’s a quick recap of the six ingredients. This is what to look for in a dream job:

- Engaging work that lets you enter a state of flow (freedom, variety, clear tasks, feedback).

- Work that helps others.

- Work you’re good at.

- Supportive colleagues.

- No major negatives, like long hours or unfair pay.

- A job that fits your personal life.

(Read more about our evidence for these six ingredients.)

How can we sum this all up?

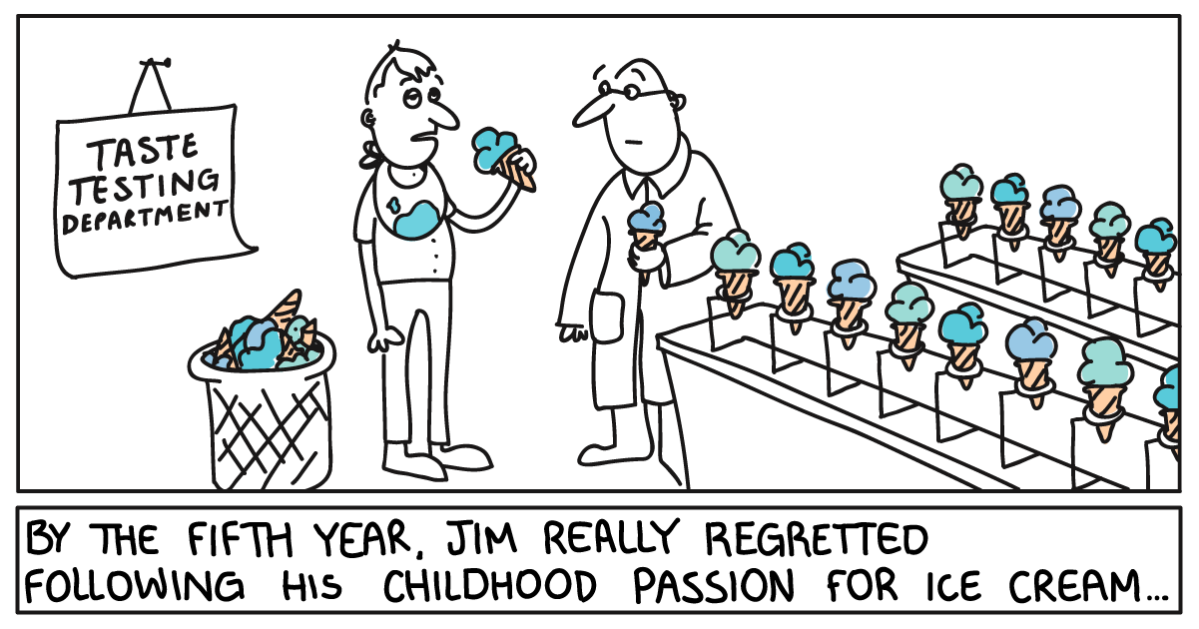

Should you just follow your passion?

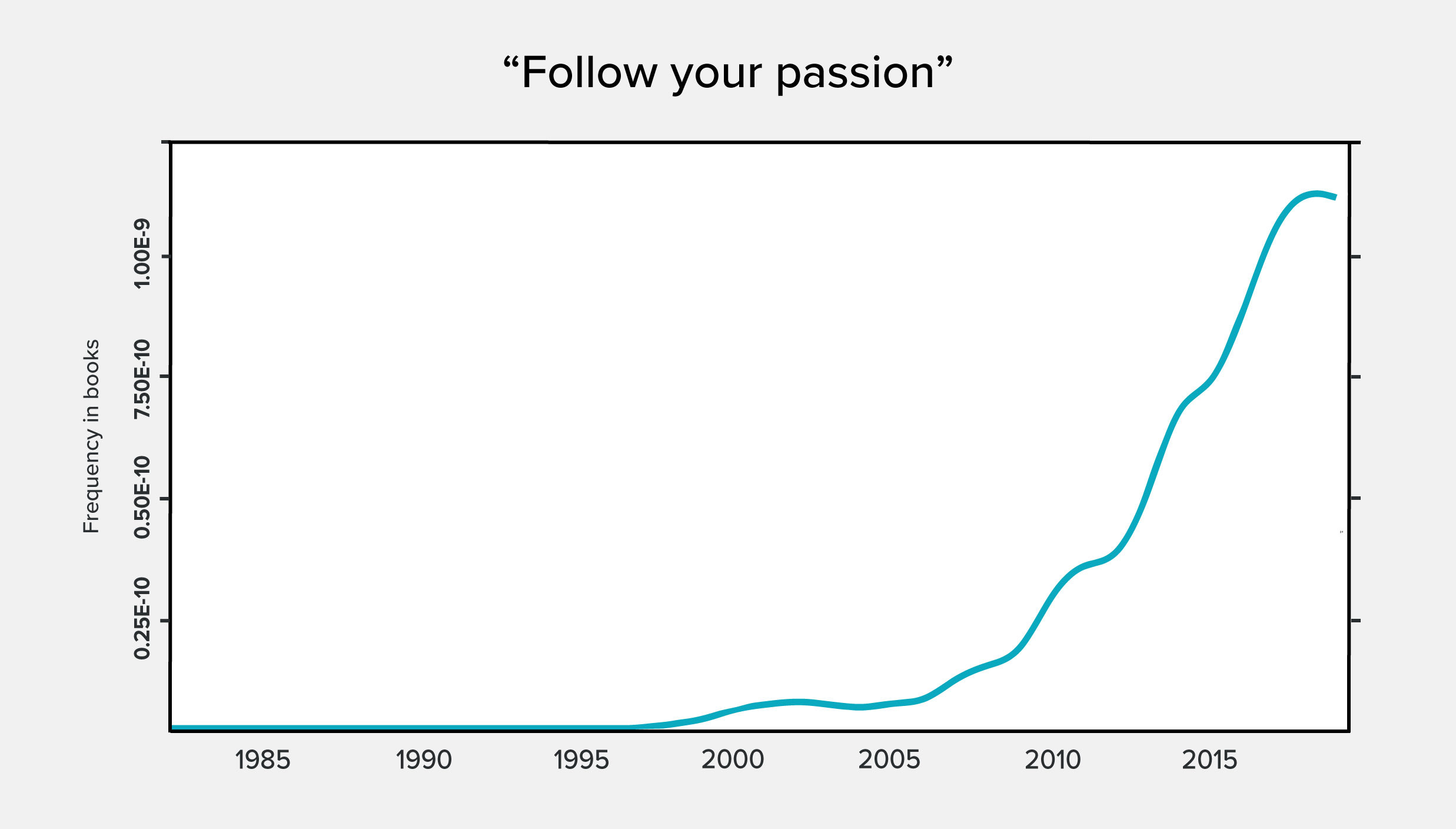

“Follow your passion” has become a defining piece of career advice.

The idea is that the key to finding a great career is to identify your greatest interest — “your passion” — and pursue a career involving that interest. It’s an attractive message: just commit to your passion, and you’ll have a great career. And when we look at successful people, they are often passionate about what they do.

Now, we’re fans of being passionate about your work. The research above shows that intrinsically motivating work makes people a lot happier than a big paycheque.

However, there are three ways “follow your passion” can be misleading advice.

One problem is that it suggests that passion is all you need. But even if you’re deeply interested in the work, if you lack the six ingredients from above, you’ll still be unsatisfied. If a basketball fan gets a job involving basketball, but works with people they hate, receives unfair pay, or finds the work meaningless, they are still going to dislike their job.

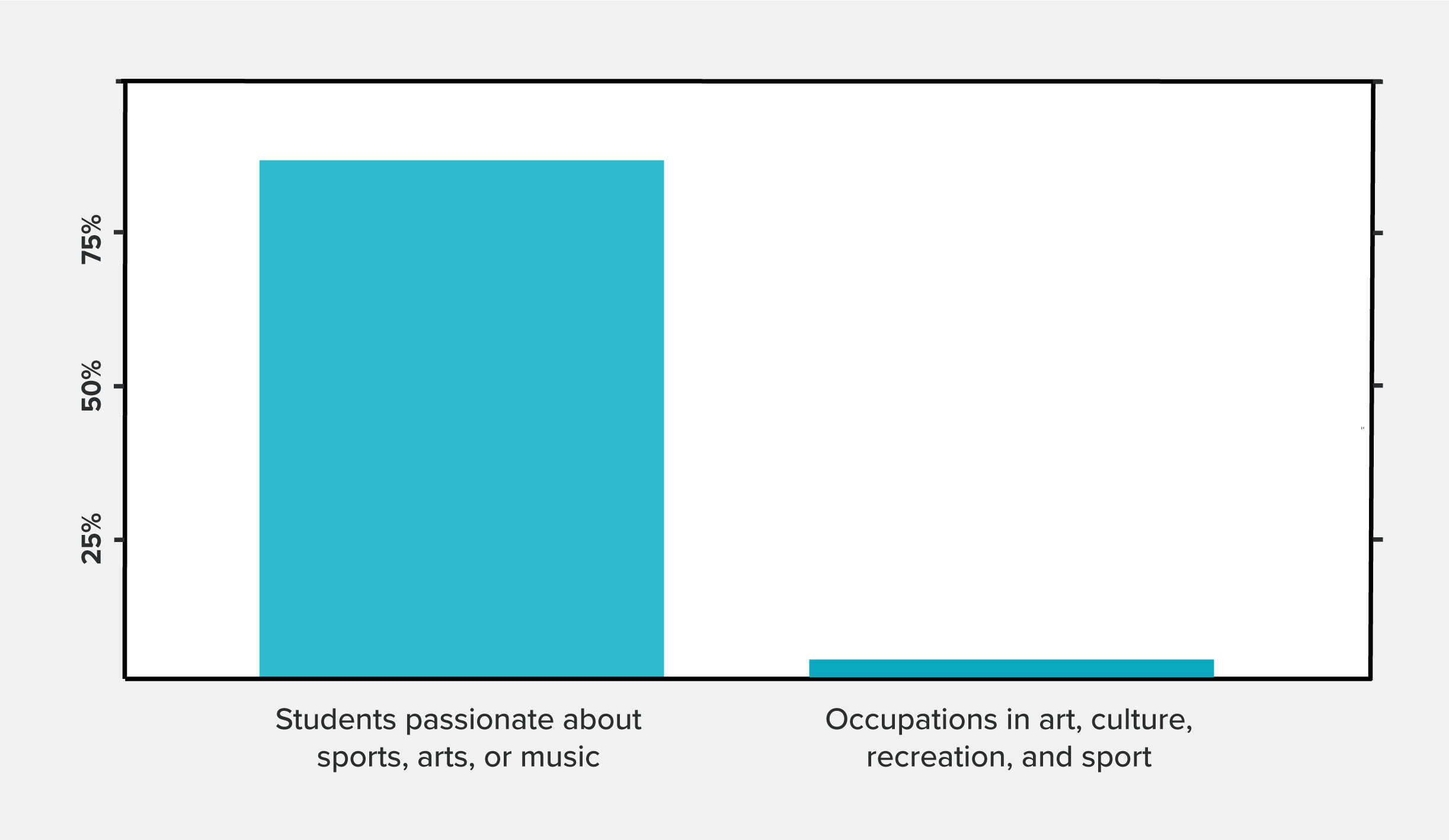

In fact, “following your passion” can make it harder to satisfy the six ingredients, because the areas you’re passionate about are likely to be the most competitive, which makes it harder to find a good job.

A second problem is that many people don’t feel like they have a career-relevant passion. Telling them to “follow their passion” makes them feel inadequate. If you don’t have a “passion,” don’t worry — you can still find work you’ll become passionate about.

And the third problem is that it can make people needlessly limit their options. If you’re interested in literature, it’s easy to think you must become a writer to have a satisfying career, and ignore other options. It’s also easy to have the idea that your “one true passion” will be immediately obvious, and eliminate options that aren’t immediately satisfying.

But in fact, you can become passionate about new areas. If your work helps others, you practice to get good at it, you work on engaging tasks, and you work with people you like, then you’ll become passionate about it. The six ingredients are all about the context of the work, not the content. Twenty years ago, we would never have imagined being passionate about giving career advice, but here we are, writing this article.

Many successful people are passionate, but often their passion developed alongside their success, and took a long time to discover, rather than coming first. Steve Jobs started out passionate about Zen Buddhism. He got into technology as a way to make some quick cash. But as he became successful, his passion grew, until he became the most famous advocate of “doing what you love.”

In reality, rather than having a single passion, our interests change often, and more than we expect. Think back to what you were most interested in five years ago, and you’ll probably find that it’s pretty different from what you’re interested in today. And as we saw above, we’re bad at knowing what really makes us happy.

This all means you have more options for a fulfilling career than you think.

A quick aside before we go on. If you’re finding this guide useful, we’d really appreciate it if you could share the article on Twitter, and help us reach more people.

Do what contributes

Rather than “follow your passion,” our slogan for a fulfilling career is: get good at something that helps others. Or simply: do what contributes.

We highlight “get good” because if you find something you’re good at that others value, you’ll have plenty of career opportunities, which gives you the best chance of finding a dream job with all the other ingredients — engaging work, supportive colleagues, lack of major negatives, and fit with the rest of your life.

You can have all the other five ingredients, however, and still find your work meaningless. So you need to find a way to help others too.

If you prioritise making a valuable contribution to the world first, you’ll develop passion for what you do — you’ll become more content, ambitious, and motivated.

This is what we’ve found in our career advising. For instance, Jess was interested in philosophy as an undergraduate, and considered pursuing a PhD. The problem was that although she finds philosophy interesting, it would have been hard to make a positive impact within it. Ultimately, she thought this would have made it unfulfilling. Instead, she switched into psychology and public policy, and became one of the most motivated people we know.

“80,000 Hours has nothing short of revolutionised the way I think about my career.”

To date, thousands of people have made major changes to their career path by following our career advice. Many switched into a field that didn’t initially interest them, but that they believed was important for the world. After developing their skills, finding good people to work with, and finding the right role, they’ve become deeply satisfied.

Here are two more reasons to focus on getting good at something that helps others.

You could be more successful

If you make it your mission to help others, then people will want to help you succeed.

This sounds obvious, and there’s now empirical evidence to back it up. In the excellent book Give and Take, Professor Adam Grant argues that people with a “giving mindset” end up among the most successful. This is both because they get more help, and because they’re more motivated by a sense of purpose.

One caveat is that givers also end up unsuccessful if they focus too much on others, and burn out. So you also need the other ingredients of job satisfaction we mentioned earlier, and to set limits on how much you give.

It’s the right thing to do

The idea that helping others is the key to being fulfilled is hardly a new one. It’s a theme from most major moral and spiritual traditions:

Set your heart on doing good. Do it over and over again and you will be filled with joy.

– BuddhaA man’s true wealth is the good he does in this world.

– MuhammadLove your neighbour as you love yourself.

– Jesus ChristEvery man must decide whether he will walk in the light of creative altruism or in the darkness of destructive selfishness.

– Martin Luther King, Jr.

What’s more, as we’ll explain in the next article, as a college graduate in a developed country today, you have an enormous opportunity to help others through your career. Ultimately, this is the real reason to focus on helping others — the fact that it’ll make you more personally fulfilled is just a bonus.

Conclusion

To have a dream job, don’t worry too much about money and stress, and don’t endlessly self-reflect to find your one true passion.

Rather, get good at something that helps others. It’s best for you, and it’s best for the world. This is the reason we set up 80,000 Hours — our mission is to help you find a career that contributes.

But which jobs help people? Can one person really make much difference? That’s what we’ll answer in the next article.

Apply this to your own career

These six ingredients, especially helping others and getting good at your job, can act as guiding lights — they’re what to aim for to find in a dream job long term.

Here are some exercises to help you start applying them.

- Practice using the six ingredients to make some comparisons. Pick two options you’re interested in, then score them from 1 to 5 on each factor.

- The six ingredients we list are only a starting point. There may be other factors that are especially important to you, so we also recommend doing the following exercises. They’re not perfect — as we saw earlier, our memories of what we’ve found fulfilling can be unreliable — but completely ignoring your past experience isn’t wise either.17 These questions should give you hints about what you find most fulfilling:

- When have you been most fulfilled in the past? What did these times have in common?

- Imagine you just found out you’re going to die in 10 years. What would you spend your time doing?

- Can you make any of our six factors more specific? For example, what kinds of people do you most like to work with?

- Now, combine our list with your own thoughts to determine the four to eight factors that are most important to you in a dream job.

- When you’re comparing your options in the future, you can use this list of factors to work out which is best. Don’t expect to find an option that’s best on every dimension; rather, focus on finding the option that’s best on balance.

Ask the author a question about this article on Twitter.

Read next: Part 2: Can one person make a difference? What the evidence says.

Or see an overview of the whole career guide.

Notes and references

- There has been an extensive programme of research into how good humans are at predicting the effects of future events on their emotional wellbeing. It began with Kahneman and Snell in the early 1990s, and was led in the 2000s by Harvard psychologist Daniel Gilbert. Much of the research is summarised in Gilbert’s book Stumbling on Happiness. A 2009 review is in Gilbert and Wilson (2009). One takeaway is that we are bad at predicting how we will feel in the future, and we don’t realise this. We’ve previously written about our failures to predict how we will feel here.

We’re unsure how robust all of these findings are be in light of the replication crisis, and haven’t found any more recent work replicating these findings.

In particular, we’re concerned about Gilbert’s prominent rejection of the existence of the replication crisis, published in Science in 2016. A convincing response to Gilbert was also published in Science in 2016, and we enjoyed this blog summarising the issue by Columbia statistician Andrew Gelman.

So we expect Gilbert has overstated the findings. Nevertheless, we think the broader point that we can’t simply trust our intuition about these matters is correct.↩

- While many studies have found support for the “peak–end rule” — the idea that we judge experiences based on how we feel at the most intense point (i.e. the peak, and at the end) — some have cast doubt on it.

For instance, Kemp et al. (2008) found that the peak–end rule was “not an outstandingly good predictor,” and that the most memorable or unusual moments (not necessarily the most intense moments) were more relevant predictors of recalled happiness. This suggests the “peak” is less relevant than the end.

The peak–end rule predicts approximately the correct level of happiness, but the correlations of the peak–end average with the overall recalled happiness are generally lower than those obtained by considering the participants’ happiness in the most memorable or most unusual 24-h period… Remembered overall happiness seems to be better predicted by end happiness than by peak or trough happiness, and the comparative failure of the peak–end rule appears to stem more from the peak than from the end.

That said, a 2022 meta-analysis looking at 58 independent studies, with a cumulative sample size of around 12,500 people, found “strong support” for the peak–end rule.

The peak-end effect on retrospective summary evaluations was: (1) large (r = 0.581, 95% Confidence Interval = 0.487–0.661), (2) robust across boundary conditions, (3) comparable to the effect of the overall average (mean) score and stronger than the effects of the trend and variability across all episodes in the experience, (4) stronger than the effects of the first (beginning) and lowest intensity (trough) episodes, and (5) stronger than the effect of the duration of the experience (which was essentially nil, thereby supporting the idea of duration neglect).↩

- CareerCast’s 2015 methodology is described here (retrieved 2-March-2016).

We’re using CareerCast’s 2015 rankings because we want to compare these rankings with measurements of job satisfaction and meaningfulness. The most recent large survey on job satisfaction and meaningfulness that we could find was conducted by Payscale (archived link, retrieved 17-August-2022), with data collected from 2.7 million people between 6-November-2013 and 6-November-2015.

CareerCast’s 2021 methodology largely unchanged and is described here (retrieved 27-September-2022).↩

- Actuary was the top-ranked career in 2015. (retrieved 2-Mar-2016).

Actuary dropped to ninth place in the 2021 rankings. (retrieved 5-Dec-2022).↩

- The most recent national survey by the UK’s Cabinet Office on life satisfaction by occupation was conducted in 2014 (and published by the University of Kent). The survey found “actuaries, economists and statisticians” ranked 64th out of 274 job titles, putting them in the top 23%.

In the more recent 2021 CareerCast survey, actuary was no longer top, but it was still ranked in the top 10 (retrieved 27-September-2022).

BBC summary, Archived link, retrieved 15-April-2017.↩

- Payscale’s surveys cover millions of workers. The most recent survey which asked about job satisfaction and job meaningfulness was conducted from 2013 to 2015. The survey found that only 36% of actuaries found their work meaningful. Job satisfaction was also high at 80%, but a significant number of jobs were rated over 80%.

http://www.payscale.com/data-packages/most-and-least-meaningful-jobs/full-list.↩

- A Gallup survey in October 2021 asked 13,085 US employees what was most important to them when deciding whether to accept a new job offered by a new employer. 64% of people said that “a significant increase in income or benefits” was “very important,” compared to 61% for “greater work-life balance and better personal well-being,” 58% for “the ability to do what they do best” and 53% for “greater stability and job security.”

The survey was a self-administered web survey. There are a number of possible sources of bias. For example, if this survey was paid (it’s unclear from the Gallup methodology), this may have introduced bias. That said, Gallup did weight samples to correct for nonresponse by adjusting the sample to match the national demographics of gender, age, race, Hispanic ethnicity, education, and region.

Archived link, retrieved 16-Feb-2023.↩

When individuals are asked what would most improve the quality of their lives, the most common response is a higher income

Judge, Timothy A., et al. “The relationship between pay and job satisfaction: A meta-analysis of the literature.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 77.2 (2010): 157-167.

https://web.archive.org/web/20160316230634/http://www.panglossinc.com/documents/Therelationshipbetweenpayandjobsatisfaction.pdf↩

- A 2021 study found that wellbeing does rise with income, even above $75,000 a year. However, it found that this, like life satisfaction, was approximately logarithmic — as an individual’s income increases, their wellbeing increases at a slower and slower rate. As a result, above $75,000 a year, the wellbeing increases are very small. The study also found that, as income increased, wellbeing rose more slowly than life satisfaction (which was also approximately logarithmic). Read a critical review of the study. A later analysis of the data revealed that the happier people were, the less their returns diminished. The happiest people continued to become happier with incomes of over $100,000, but the least happy people see almost no benefit of this income on their happiness.↩

- Killingsworth, Matthew A., Daniel Kahneman, and Barbara Mellers. “Income and emotional well-being: A conflict resolved.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 120.10 (2023): e2208661120.

“The critical observation is that Fig. 1A shows the distribution of happiness to be markedly lopsided. In the range of high incomes, in particular, the average reported positive affect is 89% of a perfect score (equivalent to 2.67 on a 0 to 3 scale) and the average of two not-blue items is 81% of the maximum. For example, on average, each dichotomous positive affect item distinguishes between a happier 89% of people and a less happy 11% of people, while the composite report combines three such items. We know, of course, that happy people are not all equally happy. In MK’s experience sampling data, for example, the distribution of happiness was approximately normal. The high density of maximum scores in the KD items indicates that the items do not adequately discriminate among degrees of happiness—there is a ceiling effect.

An example illustrates the relevance of a ceiling effect to the naming of a variable. Imagine a test of cognitive functioning which consists of items that most elderly patients pass easily, with a few exceptions due to inattention or momentary confusion. Such a test would rightly be considered a measure of dementia: the number of items failed is an indication of the severity of dementia, but the scale does not discriminate among levels of normal cognitive functioning because most normal people get the same perfect score. A similar argument implies that KD’s affect items are best interpreted as measures of unhappiness.”↩

- The average household in the US has 2.5 people, but of course this is just an average across a wide range of family structures. Larger households enjoy “economies of scale” by sharing houses, cars, and so on. This makes it tricky to say what the equivalent of a household income is for a single individual.

Standard conversion rates are the following:

- A single individual has an equivalence score of 1.

- A single extra adult adds another equivalence score of 0.5.

- Adding a young child to this adds an equivalence score of 0.3, while a teenager costs another 0.5.

As a result, a couple can achieve the same lifestyle as an individual with 50% more income; a couple with a young child can achieve the same lifestyle as an individual with 80% more income; a couple with a teenager require an income twice as high.

These are approximations, but reasonable ones used by international organisations. They are described here by the UK Institute for Fiscal Studies. (The IFS table gives conversion rates from a childless couple to a household. Dividing by 0.67 — the conversion rate to a single individual — will give you the numbers we listed above.)

For the sake of simplicity we will assume that on average across their adult lives people are in a household with an adult couple and a child. This is just an average — some people will be single, while some will be supporting multiple children, at least for some of their lives.

Using this approximation means that a single individual requires about 1/1.9 = 53% as much as a typical household, averaged over their adult lives, to achieve the same standard of living.

In this case, 53% of $90,000 for a household represents $47,700 for an individual.↩

- College grad earnings

Source:

Carnevale, Anthony P., Ban Cheah, and Emma Wenzinger. “The college payoff: More education doesn’t mean more earnings” (2021).A bachelor’s degree holder earns, at the median, $2.8 million during a lifetime, which translates into average annual earnings of about $70,000.

This figure was for 2021, but wages have grown since then. In January 2021, average wages per hour in the US were $29.92 and were $33.03 in January 2023. That’s growth of 10%, which suggests that the average college graduate now earns $77,000. This is likely an overestimate, because college graduate earnings have been growing slower than average earnings since 2021. Source: FRED Economic Data, “Average Hourly Earnings of All Employees: Total Private (CES0500000003)”, retrieved 5-Feb-2017. This growth matches roughly what we’d expect from inflation, which was about 10% over the period, and wages tend to lag inflation in high-inflation periods like 2021–23.

Mean earnings for US Ivy League graduates

It’s hard to find comparable data for just Ivy League graduates. Payscale found a median mid-career salary of over $135,000, where mid-career is defined as over 10 years.

Archived link, retrieved 23 Feb 2023.

Our guess is that the Payscale data is too high, because people with higher incomes will be more likely to fill out the survey. On the other hand, income only peaks after 20–30 years, so the figure for 10+ years probably underreports the overall average. Moreover, the median will be less than the mean.

Overall, we’re pretty confident that the mean lifetime average for Ivy League graduates is over $120,000.

If you want to estimate your future income, then you should also account for future wage growth (which has been about 2% historically). We ignore this here, and only estimate current income.↩

- Based on payscale.com surveys of over 2.7 million Americans.

Retrieved 2 November 2023http://www.payscale.com/data-packages/most-and-least-meaningful-jobs/least-meaningful-jobs

http://www.payscale.com/data-packages/most-and-least-meaningful-jobs/most-meaningful-jobs

http://www.payscale.com/data-packages/most-and-least-meaningful-jobs/methodology↩

- A 2018 meta-analysis found that there is a causal link between performing acts of kindness and wellbeing. They included 27 experimental studies included in the review, with a total sample size of 4,045 people.

These 27 studies, some of which included multiple control conditions and dependent measures, yielded 52 effect sizes. Multi-level modeling revealed that the overall effect of kindness on the well-being of the actor is small-to-medium (δ = 0.28). The effect was not moderated by sex, age, type of participant, intervention, control condition or outcome measure. There was no indication of publication bias.↩

- This is the study we quoted: Aknin, Lara, Christopher P. Barrington-Leigh, Elizabeth W. Dunn, John F. Helliwell, Robert Biswas-Diener, Imelda Kemeza, Paul Nyende, Claire Ashton-James, Michael I. Norton (2010). “Prosocial Spending and Well-Being: Cross-Cultural Evidence for a Psychological Universal.” Harvard Business School Working Paper 11-038. Link.

Though there is some evidence that part of the reason for the correlation is that happier people give more. See: Boenigk, S. & Mayr, M.L. J Happiness Stud (2016) 17: 1825. doi:10.1007/s10902-015-9672-2. Link.

For a more comprehensive review of the question, see Giving without sacrifice, by Andreas Mogensen, Giving What We Can Research, Archived Link, retrieved 6 April 2017.↩ - For example, if you’re considering having children, you’ll want to consider paths that provide a good balance for you and your family — we had a whole podcast episode about how to think about this in an evidence-driven way with economist Emily Oster.↩

- You can get more accurate information on what you enjoy over time by rating your happiness at the end of each day. That way you don’t need to rely on unreliable memory.↩