Part 2: Can one person make a difference? What the evidence says.

It’s easy to feel like one person can’t make a difference. The world has so many big problems, and they often seem impossible to solve.

So when we started 80,000 Hours — with the aim of helping people do good with their careers — one of the first questions we asked was, “How much difference can one person really make?”

We learned that while many common ways to do good (such as becoming a doctor) have less impact than you might first think, others have allowed certain people to achieve an extraordinary impact.

In other words, one person can make a difference — but you might have to do something a little unconventional.

In this article, we start by estimating how much good you could do by becoming a doctor. Then, we share some stories of the highest-impact people in history, and consider what they mean for your career.

Reading time: 12 minutes

Table of Contents

How much impact do doctors have?

Many people who want to help others become doctors. One of our early readers, Dr Greg Lewis, did exactly that. “I want to study medicine because of a desire I have to help others,” he wrote on his university application, “and so the chance of spending a career doing something worthwhile I can’t resist.”

So, we wondered: how much difference does becoming a doctor really make? We teamed up with Greg to find out.

Since a doctor’s primary purpose is to improve health, we tried to figure out how much extra “health” one doctor actually adds to humanity. We found that, over the course of their career, an average doctor in the UK will enable their patients to live about an extra combined 100 years of healthy life, either by extending their lifespans or by improving their overall health. There is, of course, a huge amount of uncertainty in this figure, but the real figure is unlikely to be more than 10 times higher.

Using a standard conversion rate (used by the World Bank, among other institutions1) of 30 extra years of healthy life to one “life saved,” 100 years of healthy life is equivalent to about three lives saved. This is clearly a significant impact; however, it’s less of an impact than many people expect doctors to have over their entire career.

There are three main reasons this impact is lower than you might expect:

- Researchers largely agree that medicine has only increased average life expectancy by a few years. Most gains in life expectancy over the last 100 years have instead occurred due to better nutrition, improved sanitation, increased wealth, and other factors.

Doctors are only one part of the medical system, which also relies on nurses and hospital staff, as well as overhead and equipment. The impact of medical interventions is shared between all of these elements.

Most importantly, there are already a lot of doctors in the developed world, so if you don’t become a doctor, someone else will be available to perform the most critical procedures. Additional doctors therefore only enable us to carry out procedures that deliver less significant and less certain results.

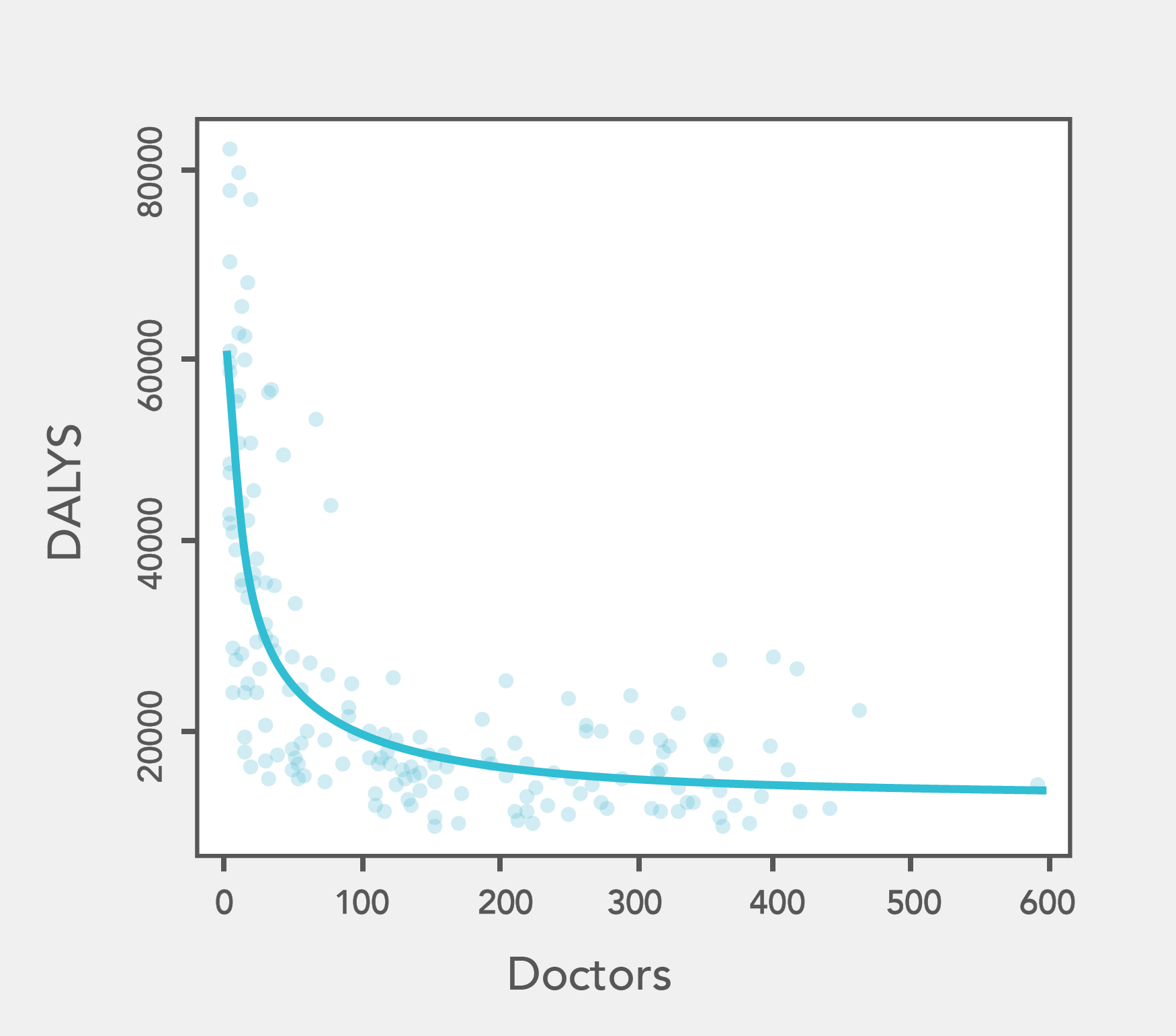

This last point is illustrated by the chart below, which compares the impact of doctors in different countries. The y-axis shows the amount of ill health in the population, measured in disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) per 100,000 people, where one DALY equals one year of life lost due to ill health. The x-axis shows the number of doctors per 100,000 people.

You can see that the curve goes nearly flat once you have more than 150 doctors per 100,000 people. After this point (which almost all developed countries meet), additional doctors only achieve a small impact on average.

So if you become a doctor in a rich country like the US or UK, you may well do more good than you would in many other jobs, and if you are an exceptional doctor, then you’ll have a bigger impact than these averages. But it probably won’t be a huge impact.

In fact, in the next article, we’ll show how almost any college graduate can do more to save lives than a typical doctor. And in the rest of the career guide, we’ll cover many other examples of common but ineffective attempts to do good.

These findings motivated Greg to switch from clinical medicine into biosecurity, for reasons we’ll explain over the rest of the guide.

Who were the highest-impact people in history?

Despite this uninspiring statistic about how many lives a doctor saves, some doctors have had much more impact than this. Let’s look at some examples of the highest-impact careers in history, and see what we might learn from them. First, let’s turn to medical research.

By 1968, it had been shown that a solution of glucose and salt, administered via feeding tube or intravenous drip, could prevent death due to cholera. But millions of people were still dying every year from the disease. While working in a refugee camp on the border of Bangladesh and Burma, Dr David Nalin sought to turn this insight into a therapy that could be used in poor rural areas. He showed in a study that simply drinking a solution made at the right concentration and consumed at the right rate could be almost as effective as delivery via feeding tube or IV.

This meant the treatment could be delivered with no equipment, and using extremely cheap and widely available ingredients.

Since then, this astonishingly simple treatment has been used all over the world, and the annual rate of child deaths from diarrhoea has plummeted from around 5 million to 1.5 million.2 Researchers estimate that the therapy has saved over 50 million lives to date, mostly children’s.3

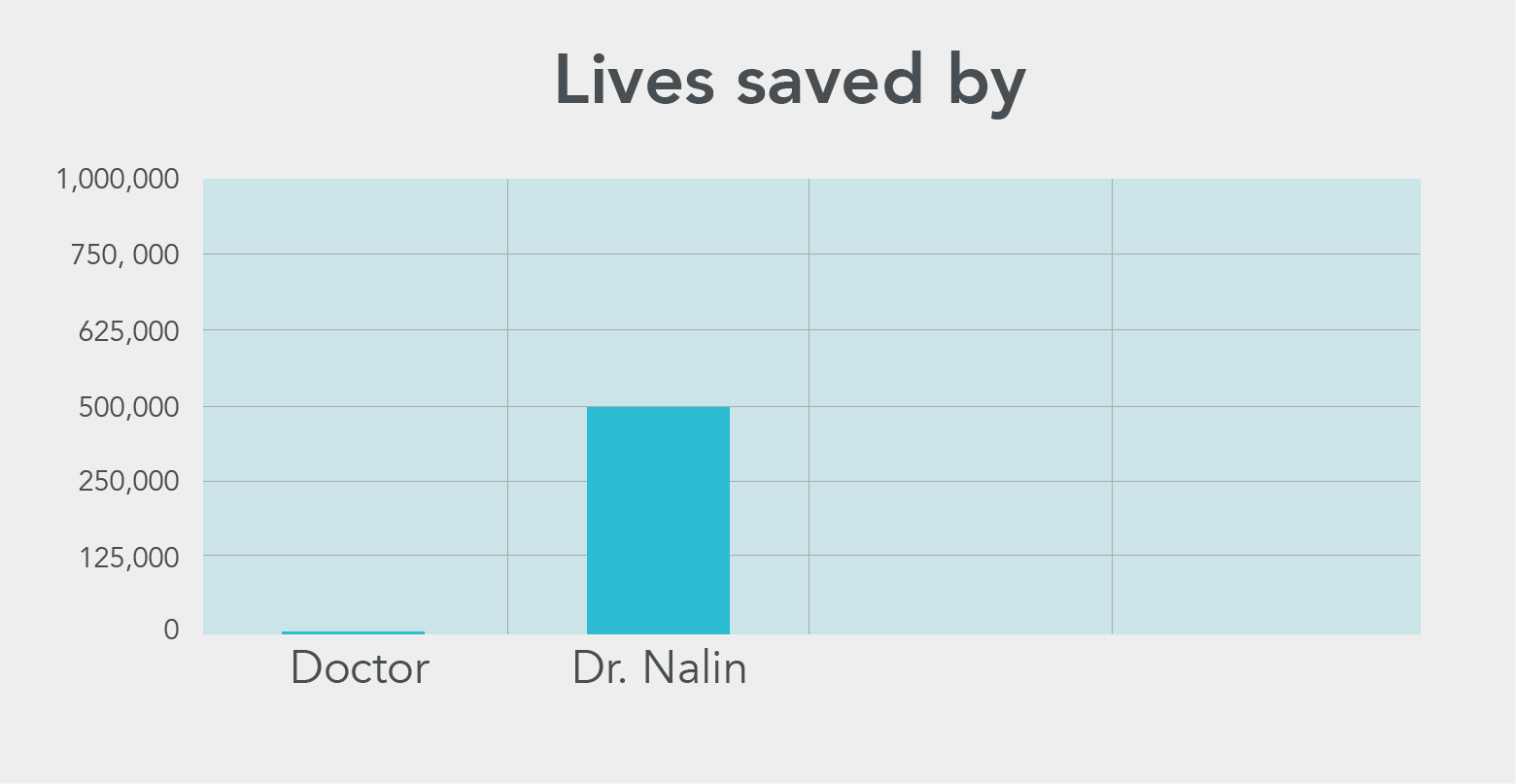

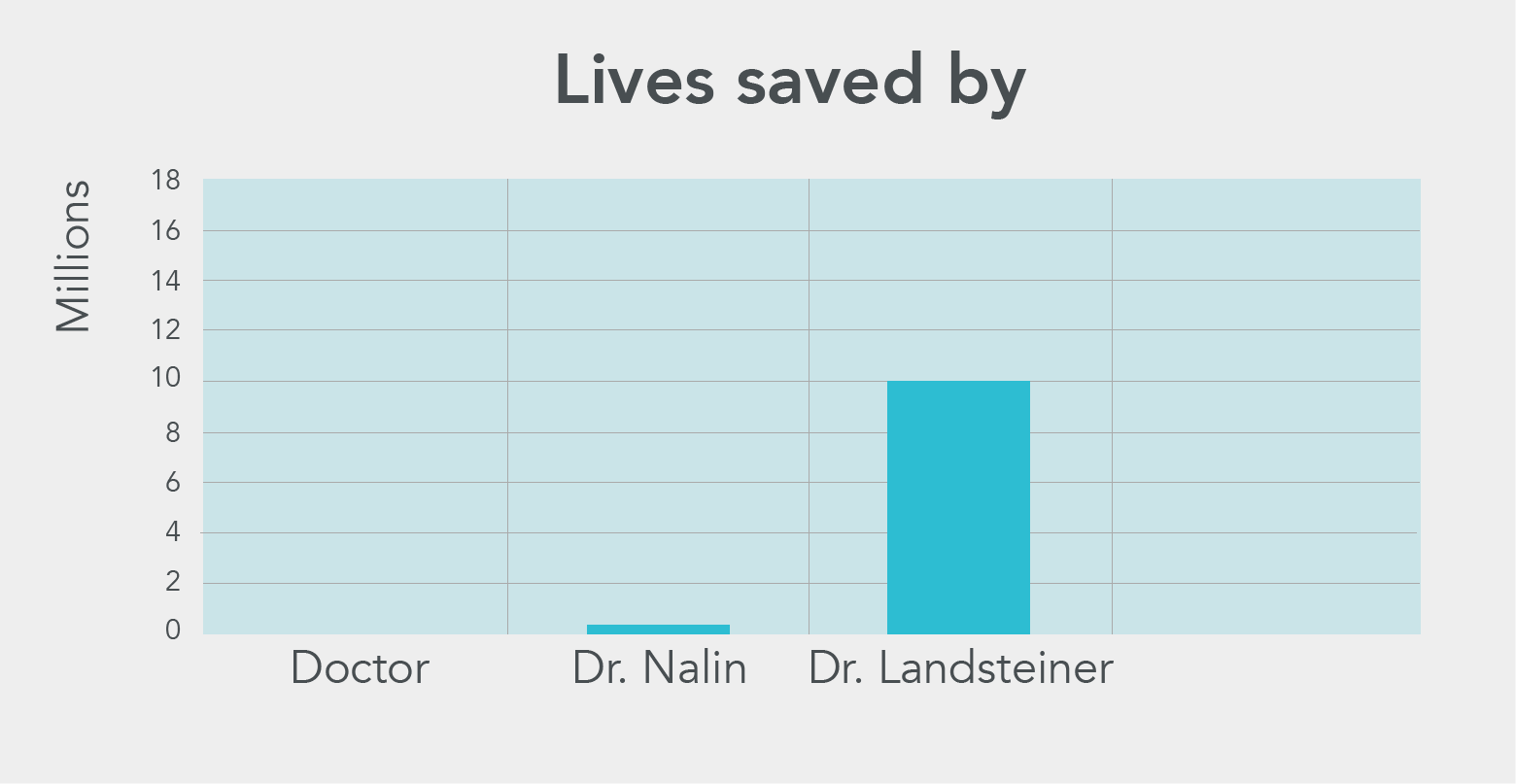

If Dr Nalin had not been around, someone else would, no doubt, have discovered this treatment eventually. However, even if we imagine that he sped up the roll-out of the treatment by only five months, his work alone would have saved about 500,000 lives. This is a very approximate estimate, but it makes his impact more than 100,000 times greater than that of an ordinary doctor:

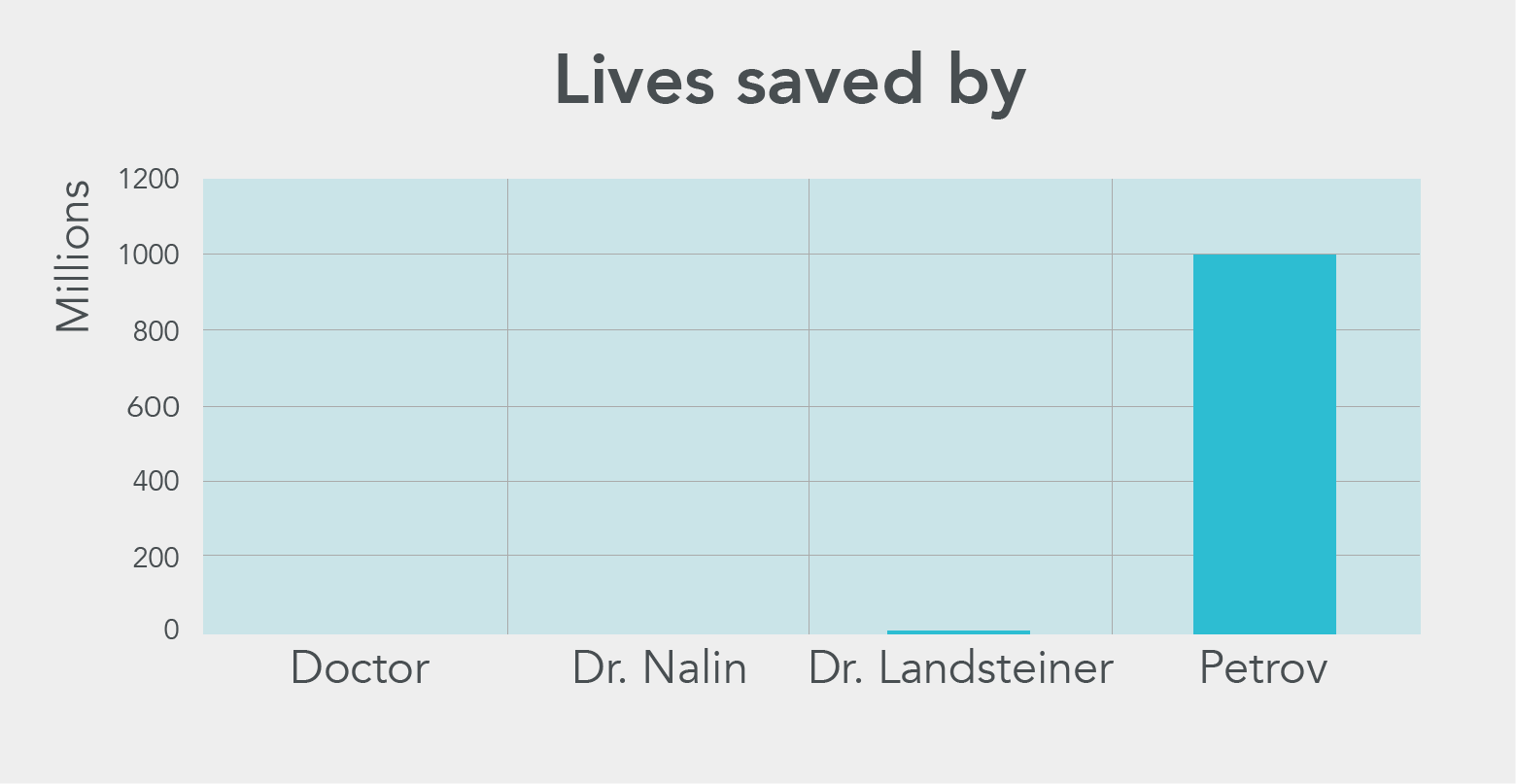

But even just within medical research, Dr Nalin is far from the most extreme example of a high-impact career. For example, one estimate puts Karl Landsteiner’s discovery of blood groups as saving tens of millions of lives by enabling transfusions.4

Beyond the medical field, later in the guide we’ll cover the stories of a hugely impactful mathematician, Alan Turing, and bureaucrat, Viktor Zhdanov.

Or, let’s think even more broadly. Roger Bacon and Galileo pioneered the scientific method — without which none of the discoveries we covered above would have been possible, along with other major technological breakthroughs like the Industrial Revolution. These individuals were able to do vastly more good than even outstanding medical practitioners.

The unknown Soviet Lieutenant Colonel who saved your life

Or consider the story of Stanislav Petrov, a Lieutenant Colonel in the Soviet Army during the Cold War. In 1983, Petrov was on duty in a Soviet missile base when early warning systems apparently detected an incoming missile strike from the United States. Protocol dictated that the Soviets order a return strike.

But Petrov didn’t push the button. He reasoned that the number of missiles was too small to warrant a counterattack, thereby disobeying protocol.

If he had ordered a strike, there’s at least a reasonable chance hundreds of millions would have died. The two countries may have even ended up engaged in an all-out nuclear war, leading to billions of deaths and, potentially, the end of civilisation. If we’re being conservative, we might quantify his impact by saying he saved a billion lives. But that’s almost certainly an underestimate, because a nuclear war would also have devastated scientific, artistic, economic, and all other forms of progress, leading to a huge loss of life and wellbeing over the long run.

Later in the guide we’ll discuss why we think these long-run effects could be vastly more important than “just” saving a billion lives from nuclear catastrophe.

Yet even with the lower estimate, Petrov’s impact likely dwarfs that of Nalin and Landsteiner.

What do these differences in impact mean for your career?

We’ve seen that some careers have had huge positive effects, and some have vastly more than others.

Some component of this is due to luck — the people mentioned above were in the right place at the right time, giving them the opportunity to have an impact that they might not have otherwise received. You can’t guarantee you’ll make an important medical discovery.

But it wasn’t all luck: Landsteiner and Nalin chose to use their medical knowledge to solve some of the most harmful health problems of their day, and it was foreseeable that someone high up in the Soviet military might have the opportunity to have a large impact by preventing conflict during the Cold War.

So, what does this mean for you?

People often wonder how they can “make a difference,” but if some careers can result in thousands of times more impact than others, this isn’t the right question. Two different career options can both “make a difference,” but one could be dramatically better than the other.

Instead, the key question is: What are some of the best ways to make a difference? In other words, what can you do to give yourself a chance of having one of the highest-impact careers? Because the highest-impact careers achieve so much, a small increase in your chances means a great deal.

The examples above also show that the highest-impact paths might not be the most obvious ones. Being an officer in the Soviet military doesn’t sound like the best career for a would-be altruist, but Petrov probably did more good than our most celebrated leaders, not to mention our most talented doctors. Having a big impact might require doing something a little unconventional.

So how much impact can you have if you try, while still doing something personally rewarding? It’s not easy to have a big impact, but there’s a lot you can do to increase your chances. That’s what we’ll cover in the next couple of articles.

But first, let’s clarify what we mean by “making a difference.” We’ve been talking about lives saved so far, but that’s not the only way to do good in the world.

What does it mean to “make a difference”?

Everyone talks about “making a difference” or “changing the world” or “doing good,” but few ever define what they mean.

So here’s a definition. Your social impact is given by:

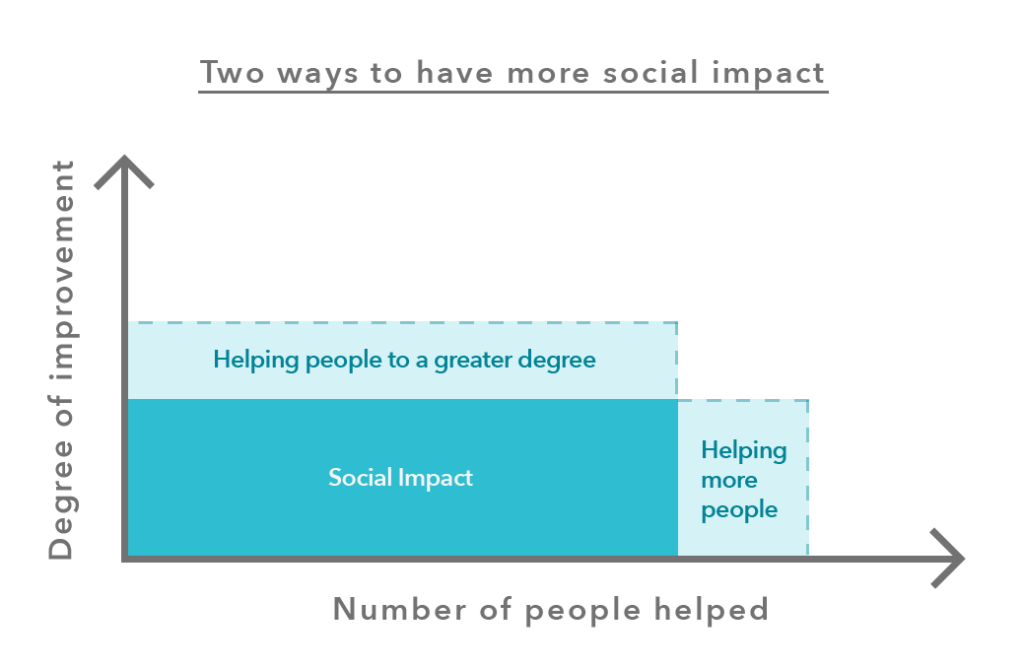

The number of people5 whose lives you improve, and how much you improve them, over the long term.6

This means you can increase your social impact in three ways:

- By helping more people.

- By helping the same number of people to a greater extent (pictured below).

- By doing something which has benefits that last for a longer time.

We think the last option is especially important, because many of our actions affect future generations. For example, if you improve the quality of government decision-making, you might not see many quantifiable short-term results, but you will have solved lots of other problems over the long term.

Why did we choose this definition?

We have a separate article about our definition, but here are some brief points:

Many people disagree about what it means to make the world a better place. But most agree that it’s good if people have happier, more fulfilled lives, in which they reach their potential. So, our definition is narrow enough that it captures this idea.

Moreover, as we’ll show, some careers do far more to improve lives than others, so it captures a really important difference between options. If some paths can do good equivalent to saving hundreds of lives, while others have little impact at all, that’s an important difference.

But the definition is also broad enough to cover many different ways to make the world a better place. It’s even broad enough to cover environmental protection, since if we let the environment degrade, the future of civilisation might be threatened. In that way, protecting the environment improves lives.

Importantly, having a broad scope also allows us to include nonhuman animals, as well as potential future sentient beings that might be entirely digital — which is why we have profiles on factory farming, wild animal welfare, and artificial sentience.

That said, the definition doesn’t include everything that might matter. You might think the environment deserves protection even if it doesn’t make people better off. Similarly, you might value things like justice and aesthetic beauty for their own sakes.

In practice, our readers value many different things. Our approach is to focus on how to improve lives, and then let people independently take account of what else they value. To make this easier, we try to highlight the main value judgements behind our work. It turns out there’s a lot we can say about how to do good in general, despite all these differences.

How can you measure social impact?

We are always uncertain about how much impact different actions will have — but that’s OK, because we can use probabilities to make comparisons. For instance, a 90% chance of helping 100 people is roughly equivalent to a 100% chance of helping 90 people. Though we’re uncertain, we can quantify our uncertainty and make progress.

Moreover, even in the face of uncertainty, we can use rules of thumb to compare different courses of action. For instance, later in this career guide we argue that, all else equal, it’s higher impact to work on neglected areas. So, even if we can’t precisely measure social impact, we can still be strategic by picking neglected areas. We’ll cover many more rules of thumb for increasing your impact in the upcoming articles.

Is social impact all that matters?

No.

We don’t know the ultimate truths of moral philosophy, but in the real world we think it’s really important not to only focus on impact.

In particular, it’s normally better — even from the perspective of social impact — to always act with good character, respect the rights and values of others, and to pay attention to your other personal values.

We don’t endorse doing something that seems very wrong from a common-sense perspective, even if it seems like it might let you have a greater impact.

Read more about our definition of social impact.

So how can you improve lives with your career?

In the next article, we’ll cover how any college graduate can make a big impact in any job. After that we’ll cover how to choose a job in which you can fulfil your potential for impact.

Read next: Part 3: No matter your job, here’s 3 evidence-based ways anyone can have a real impact

Or see an overview of the whole career guide.

Notes and references

- Source: World Bank, p. 402, retrieved 31-March-2016↩

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, Global Burden of Disease Study 2019, 2019.https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/↩

Since the adoption of this inexpensive and easily applied intervention, the worldwide mortality rate for children with acute infectious diarrhoea has plummeted from around 5 million to about 1.5 million deaths per year. Lives Saved: Over 57,500,000.

Source: Science Heroes. Archived link, retrieved 4-December-2022.

Very roughly, this means 50/40 = 1.25 million lives have been saved per year. So if Dr Nalin sped up the discovery by five months (just a guess), that means that (5/12)*1.25 = 0.52 million extra lives were saved by his actions. This is a highly approximate estimate and could easily be off by an order of magnitude. See more comments in the next footnote.↩

Superman of Science Makes Landmark Discovery – Over 1 Billion Lives Saved So Far

Every source quoted an amazing number of transfusions and potential lives saved in countries and regions worldwide. High impact years began around 1955 and calculations are loosely based on 1 life saved per 2.7 units of blood transfused. In the USA alone an estimated 4.5 million lives are saved each year. From these data I determined that 1.5% of the population was saved annually by blood transfusions and I applied this percentage on population data from 1950-2008 for North America, Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and parts of Asia and Africa. This rate may inflate the effectiveness of transfusions in the early decades but excludes the developing world entirely.

Source: Science Heroes. Archived link, retrieved 4-March-2016.

If we assume a constant number of lives saved per year, then that’s about 10 million lives per year. If he sped up the discovery by two years, then that’s 20 million lives saved.

This is a highly approximate estimate and could easily be off by an order of magnitude in either direction, and seem more likely to be too high than too low. We’re a bit sceptical of the Science Heroes figures. Moreover, our attempt at modelling the speed-up is very simple. Since most of the lives were saved in the modern era once a large number of people had medical care, it’s possible that speeding up the discovery wouldn’t have had much impact at all. On the other hand, the discovery of blood groups probably made other scientific advances possible, and we’re ignoring their impact. Nevertheless, the basic point stands: Landsteiner’s impact was likely vastly greater than a typical doctor.↩

- We often say “helping people” here for simplicity and brevity, but we don’t mean just humans — we mean anyone with experience that matters morally — e.g. nonhuman animals that can suffer or feel happiness, or even conscious machines if they ever exist.↩

- This definition is enough to help you figure out what to aim at in many situations — e.g. by roughly comparing the number of people affected by different issues. But sometimes you need a more precise definition.

The more rigorous working definition of social impact used by 80,000 Hours is:

“Social impact” or “making a difference” is (tentatively) about promoting total expected wellbeing — considered impartially, over the long term — without sacrificing anything that might be of comparable moral importance.

You can read about why we use this definition in our article on defining social impact.↩