Part 9: All the evidence-based advice we’ve found on how to be more successful in any job

The trouble with self-help advice is that it’s often based on barely any evidence. How many times have you been told to “think positively” in order to reach your goals? It’s probably the most popular piece of personal guidance, beloved by everyone from high school teachers to productivity YouTubers. An idea behind the slogan is that if you visualise your ideal future, you’re more likely to attract it.

The problem? Recent research found evidence that fantasising about your perfect life can make you less likely to make it happen. While it can be pleasant, it can reduce motivation because it makes you feel that you’ve already hit those targets.1

Insisting on positive thoughts can also lead us to suppress negative emotions, deny real problems, and even produce a backlash effect. Studies have found telling yourself positive affirmations that you don’t really believe, like “I’m a brilliant person,” can highlight the ways you fall short, making you feel worse.2 Positive thinking can be helpful, but as we’ll see, it really matters how you do it.

Much other advice is just one person’s opinion, or useless clichés. But at 80,000 Hours, we’ve found that there are a number of evidence-backed steps anyone can take to become more content, productive, and successful in their career, as well as their life in general. So we’ve gathered and reproduced them here. This list represents the best personal development advice we’ve come across over the last 15+ years.

If you’ve changed to a new career path, you can use these steps to achieve more in your new role. If you’re not ready to change careers yet, you can use them to invest in your career capital, no matter what you’re doing now.

Although the evidence isn’t always as strong as we’d like, we’ve tried to gather the best that’s available. Instead of going blindly with what “studies say,” we’ve included steps that are cheap to test, make theoretical sense, and offer a lot of upside, even if the empirical evidence for them is weaker.3 You can explore more in the further reading and footnotes for each section.

Reading time: 40 minutes

Table of Contents

- 1 0. Learn how to do self-development

- 2 1. Don’t forget to take care of yourself

- 3 2. If helpful, make mental health your top priority

- 4 3. Deal with your physical health (not forgetting your back!)

- 5 4. Set goals

- 6 5. Try out this list of ways to become more productive

- 7 6. Get better at using the latest AI tools

- 8 7. Improve your basic social skills

- 9 8. Surround yourself with great people

- 10 9. Apply scientific research into happiness

- 11 10. Use these tips to save more money

- 12 11. Use research into decision-making to think better

- 13 12. Learn how to learn

- 14 13. Be strategic about how you use your time at work

- 15 14. Become an expert

- 16 15. Become a better person

- 17 The compounding benefits of investing in yourself

- 18 Put into practice

- 19 Want to come back later?: Get the guide as a free book

0. Learn how to do self-development

We’ve put the advice roughly in order: the first items are the easiest, highest-upside, and most widely applicable steps, and then we move on to the more challenging ones.

Much of what follows is about building new habits — regular behaviours and routines that become almost automatic. So if you get better at building habits, everything else will be faster. And there’s research on how to do exactly that. Atomic Habits is a bestselling book that turns the basic behavioural science on forming habits into a very practical guide. If you’d prefer a more academic vibe, take a look at BJ Fogg’s Tiny Habits.

The key advice is to make the habit as easy and rewarding as possible. Use environmental cues (like putting your gym bag out the night before), make yourself accountable (such as by agreeing to meet your friend at the gym at 8:00 AM), and use rewards (like letting yourself watch Netflix on the treadmill).

Start small — smaller than you think. Rather than starting by aiming to do four one-hour gym sessions a week, aim to exercise for five minutes a day. Even a tiny habit you actually stick to can be built upon, shifting your identity until you are someone who exercises regularly. Over a couple of months, not much will change, but eventually you can end up in a totally different place.

It takes about 30–60 days to ingrain a new habit. That’s hard enough without starting five at once. So skim through the list below, pick the one area that you think might make the most difference to your life with the least effort, and then pick one habit or exercise from there to start.

Typically, you should focus on an area for 3–12 months, using each month to build one habit or do one exercise. Look for something you can easily fit around your existing work. As you gain momentum, you can take on bigger challenges.

1. Don’t forget to take care of yourself

To begin, an important reminder: ambitious, idealistic people often don’t take care of themselves. This can make them burn out and ultimately be less successful.

Even if you only care about helping others, it’s still important to look after yourself. Psychology professor Adam Grant wrote a book arguing that altruists who also looked out for their own interests were more productive in the long term, and so ultimately did more to help others — adding empirical backing to a perhaps obvious idea.4

To look after yourself, the most important thing is to focus on the basics: getting enough rest, exercising, eating well, and maintaining your closest friendships.

This is common sense, and research seems to back it up. These factors can have a big impact on your day-to-day happiness, not to mention your health and energy.5 In fact, as we’ve seen, they probably matter much more than other factors people tend to focus on, like money.

So, if there’s anything you can do to significantly improve one of these areas, it’s worth taking care of it first. A lot has been written about how to improve them. Sometimes there are small technical tricks (e.g. some people find they sleep far better if they wear an eyemask), but it often comes down to building better habits (e.g. scheduling a weekly call with your best friend).

Here are some quick tips and places to learn more:

- The best guide we’ve found on how to get better sleep is by Lynette Bye, who aims to summarise all the research.

- Look for other activities you find deeply relaxing and rejuvenating, and schedule them at least once a week. This could be walking in nature, taking a hot bath, shooting the shit with your friends, dance, meditation, or whatever else works for you.

- Within exercise, try to at least hit these guidelines by the UK’s National Health Service. The most important thing is to actually do it, so start with whatever activities you most enjoy. If you want to optimise further, here are some additional resources.

- Not that much is known about what makes for a good diet, but the main areas of consensus seem to be: find a system that helps you avoid eating too many calories (whether that’s low carb, low fat, intermittent fasting or something else); avoid processed foods and lots of sugar; eat plenty of protein to gain more muscle; and eat lots of plants.6 Beyond this, experiment and keep note of what makes you feel best.

- Perhaps the biggest thing you can do to maintain close friendships is to schedule regular time for them.

- If you want to keep going, here’s a list of life hacks by Alex Vermeer.

2. If helpful, make mental health your top priority

About 30% of people in their 20s have some kind of mental health issue.7 If you’re suffering from one — be it anxiety, bipolar disorder, ADHD, depression, or something else — then it’s often best to prioritise dealing with it or learning to cope better. It’s one of the best investments you can ever make — both for your own sake and your ability to help others.

We know many people who took the time to make mental health their top priority and who, having found treatments and techniques that worked, have gone on to perform at the highest level. Many of our staff have also made their mental health a major priority, and they tell their stories on the podcast.

If you’re unsure whether you have a mental health issue, it’s well worth investigating. We’ve also known people who have gone undiagnosed for decades, and then found their life was far better after diagnosis and treatment.

Don’t get hung up on whether you satisfy the criteria for a formal diagnosis. Many mental health conditions appear to lie on a spectrum (e.g. from good mood to ‘normal’ unhappiness to depression), and the point at which a formal diagnosis is made is ultimately arbitrary. What matters is not the label that’s applied, but whether you can find helpful ways to feel better.

Mental health is not our area of expertise, and we can’t offer medical advice. We’d recommend seeing a doctor as your first step, ideally a specialist psychiatrist. If you’re at university, there should be free services available. All that being said, we’ve collected some of the resources we’ve personally found most helpful for you to explore.

Besides medication, therapy is often helpful. Probably the most evidence-based form of therapy is cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), which has been found to help with many different conditions.8 Moreover, managing your emotions is just a vital life skill for everyone, and CBT is one of the main evidence-based ways of getting better at that.

One of the central ideas of CBT is that our emotions often follow from our thinking, but our thinking often tends to be unrealistically negative, so learning to spot and combat these unrealistically negative thoughts can significantly boost your mental health. This is one way that “think positively” is pointing in a good direction: having unrealistically negative beliefs isn’t helpful, but that’s not the same as denying real problems or having an inflated positive opinion of yourself.

A classic book about CBT is Feeling Good by David D. Burns. In fact, reading this book has even been tested in randomised controlled trials and found to reduce symptoms of depression, which is rather more convincing than Amazon reviews. You can also listen to two interviews with the author on the Clearer Thinking podcast, which has other great content on mental health.9 The host of this podcast, Spencer Greenberg, has developed an an online CBT app that we like.

On our podcast, we interviewed a CBT therapist, Tim LeBon, about what CBT involves and why it might be useful to our readers. We’ve also written up a list of simple CBT-inspired questions you can ask yourself whenever something bad happens in your life.

You could also explore other therapies broadly in the CBT tradition, which also tend to be practical and solution-based, such as dialectical behavioural therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy, behavioural activation, compassion-focused therapy, exposure therapy, and more. Some of our readers have also found focusing, meditation (see below), and internal family systems therapy useful for general emotional management.

With any form of therapy, a key step is finding a therapist who’s a good match. Some research has suggested that the degree of ‘therapeutic alliance’ can even be as important as the form of therapy.10 Finding a great therapist is often difficult, but here are some tips:

- Ask for referrals from friends whose judgement you trust. You can also search professional listings and online reviews, but these will be more hit-or-miss.

- Don’t feel like you need to stick with the first therapist you find. Most therapists will be happy to do an initial consultation or trial session. Speak to a couple and see who you get on with best.

- Keep in mind that therapy can be roughly divided into two very different forms: those in the tradition of psychoanalysis, which aims to identify patterns of counterproductive behaviour starting in childhood, and those in the tradition of CBT, which tend to be practical and solution focused, and have a clearer evidence base. Both can be useful, but our sympathies lie with the CBT tradition, so that’s what we’d suggest trying first.

- If you’re involved in effective altruism, you might like to check out our interview with Hannah Boettcher and Mental Health Navigator. Private practitioners include Ewelina Tur, Daystar Eld, and Tim LeBon.

- Here’s a longer guide on how to find a therapist.

Here are some additional mental health resources organised by condition:

- Some of our favourite resources are the reviews by condition and medication on Lorien Psychiatry.

- The UK’s National Health Service publishes useful, evidence-based advice on treatments for most conditions. That’s usually a good starting point.

- Depression and low mood — in addition to CBT, see this summary of treatments for depression by Scott Siskind. We’d also recommend It’s Not Always Depression by Hilary Hendel.

- Anxiety — see this summary of treatments for anxiety by Scott Alexander, and Mind Ease.

- ADHD — check out Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Adult ADHD and Taking Charge of Adult ADHD.

- Perfectionism — this seems very common among our readers, and is the focus of the first part of this podcast episode with CBT therapist Tim LeBon.

- Imposter syndrome — this is also extremely common, which is why one of our team members wrote her own guide to overcoming it.

See all of our resources on mental health.

Just as with your mental health, it also pays to focus on your physical health…

3. Deal with your physical health (not forgetting your back!)

very little evidence that you need to drink eight glasses of water a day to be healthy.

Lots of health advice is snake oil. But it’s probably also the area where the most evidence-based advice exists. Besides your doctor, you can find easy-to-use summaries of the scientific consensus on how to treat different health problems on websites like the NHS’s Health A to Z and the Mayo Clinic. More recently, a study found that AI was basically as good as a human doctor at medical diagnosis,11 though you should have an expert double-check any recommendations it makes.

We were surprised to learn that the biggest risk to our productivity is probably back pain. After car accidents, it’s the leading cause of ill-health among otherwise healthy people in high-income countries.12 Our cofounder, Will, was suddenly taken out for months by chronic lower-back pain. He spoke to over 10 health professionals about his issue before he got any useful advice. This isn’t uncommon, since the causes of back pain can vary widely, and it can be hard to treat.

Repetitive strain injury (RSI), pain caused by repetitive movements like using a mouse, is also a hazard of modern workplaces.

Nevertheless, you can reduce your chances of back pain and RSI in a few ways:

- Correctly set up your desk and maintain good posture.

- Regularly change position (methods like working for 25min and then taking a 5min break as in the pomodoro technique can be useful).

- Exercise regularly, including some strength training for the whole body (especially the posterior chain, such as Romanian deadlifts).

- If you do get any symptoms, here’s tips on about how to treat back pain and RSI.

These steps sound trivial, but statistically, it’s pretty likely you’ll face a bout of bad back pain at some point in your life, and you’ll thank yourself for making these simple investments.

4. Set goals

There’s plenty of debate about the best ways to set goals. Should you focus more on outcomes or the process? Should your goals be ambitious or achievable? These differences probably don’t matter too much. The key point is that setting goals works: people who set goals tend to achieve more — so just set some.

Longer-term goals

One place to start is to get clearer about what an ideal life would look like for you, so you can spot more effective ways of getting there. We talked about your career vision in the career planning article. Now broaden it: How would you like your life to look in five or 10 years’ time? If money were no object, or you knew you couldn’t fail, what would you do?

Don’t just think about exciting things you’d like to achieve — many external achievements don’t seem to affect happiness that much — also think about your ideal “mundane Wednesday.” What exactly would you do from waking to falling asleep, and how would you feel? The point of this is to help you clarify what you actually want and to spot the most efficient ways of getting there.13

In doing this, it’s useful to keep in mind the ingredients that are normally most important for fulfilment:

- Satisfying relationships

- Contributing to a goal beyond yourself

- Engagement and a sense of competence (where you can enter a state of ‘flow’)

- A lack of major negatives, such as financial stress, health problems, or interpersonal conflicts

You can get clearer about your values by asking yourself why you’re pursuing any goals you have over and over until you can’t think of any deeper reasons. This tool from Clearer Thinking can help. Another exercise that’s been studied is writing your own eulogy: imagine you’ve passed away — what would you like people to say about your life?

A comprehensive take on this step would look like a list of values you want to move towards, a five-year day in the life vision, and one or two other ambitious things you’d like to achieve.

Goals for the quarter

In addition to your longer-term goals, consider setting 1–2 professional and 1–2 personal goals for the next quarter or two.

I like to do an ‘annual life review’ in which I pick a broad focus for the year (e.g. testing out being a full-time writer). Then I set more specific quarterly goals, which I review at the start of each quarter. Here’s a helpful template for quarterly reviews.

For annual reviews, here’s my template. Many on the 80,000 Hours team have found Alex Vermeer’s “8,760 Hours” document (no relation) helpful, and we also developed a short one for reviewing your career specifically.

While your longer-term goals should be dedicated to setting your direction, your shorter-term goals are more about maximising your productivity. Here you might find it more helpful to set an ‘input goal’ to do something that’s under your control (e.g. write for 3 hours per day), rather than an ‘output goal’ that you could easily fail for reasons that are out of your control (e.g. finish writing a book by the end of the year). Both kinds of goal are helpful. We have more tips on how to achieve your goals in the next section.

Learn to prioritise

The 80/20 principle is the idea that 20% of tasks account for 80% of results. It could be that 20% of clients are responsible for 80% of overall sales, 20% of your friends are responsible for 80% of the parties you get invited to, or 20% of words cover 80% of the language you’re learning. In reality, the 80/20 principle is just a rough rule of thumb, but the basic idea can be very helpful. Applied to your goals, it means it’s really important to put them in order of priority and try to focus as much as possible on those at the top.14

But how do you actually figure out what will produce the best results? In “Five ways to prioritise better,” productivity coach Lynette Bye considers the five most common prioritisation techniques you can apply to goals in your own life. One example is bottleneck analysis. Ask yourself, “Which key problem would unlock the most progress in the rest of my life?” Maybe it’s a certain relationship you need to change, fixing your sleep so you have more energy, or dealing with procrastination.

To stay focused, make a list of your goals, pick the top three or so, and then put everything below that on a do not do list. Those are typically compelling but second-best activities that can easily distract us from our top priorities.

It’s normal to feel like you’re not doing enough. But if you prioritise and focus on your top priorities, then you’ll know you’re doing the best you can.

Now, once you’ve set some goals, how can you actually achieve them?

5. Try out this list of ways to become more productive

You can find lots of articles about which skills are most in-demand by employers — is it marketing, programming, or data science? But what people don’t talk about so often are the skills that are useful in all jobs — those that make you more effective at everything. We’ve already covered several examples: building habits, prioritising, and taking care of yourself. Here we’ll cover another: building the habits of personal productivity.

An example is ‘implementation intentions.’ Rather than saying “I will exercise every day,” define a specific ‘trigger’ — exactly when and where you will do it — such as: “When I get home from work, the first thing I’ll do is put on my trainers and go for a run.” This surprisingly simple technique has been found in a large meta-analysis to make people much more likely to achieve their goals — in many cases about twice as likely (effect size of 0.65).15

How to become more motivated

Psychology Professor Gabriele Oettingen wrote a whole book arguing that implementation intentions can be made even more effective by combining them with some negative thinking, specifically ‘negative contrasting.’ Here’s how it works:16

Think about your goal and why you’d like to achieve it.

Set an implementation intention for actions to achieve the goal.

Imagine you fail to achieve your goal. What went wrong?

Modify your plan to prevent that issue.

Repeat until you feel confident you’ll achieve the goal.

Doing this either helps you make a more robust plan, where you’re more mentally prepared for challenges, or helps you realise the goal isn’t realistic and needs to be modified. For one of the goals you set in the previous section, what’s most likely to prevent you from achieving it?

Another way to increase your motivation that many people we know swear by is the use of ‘commitment devices.’ Tell a friend you need to do one hour of focused work before noon each day. If you miss the target, you need to rip up $100 and send them a photo. You can use a tool like Beeminder and stickK to track these kinds of commitments.

You can find many more techniques for increasing your motivation in The Motivation Hacker, a short popular summary of the research by Nick Winter, and The Procrastination Equation by Professor Piers Steel. Grit by Angela Duckworth is about how to develop your passion and perseverance.

Productivity processes

Another way to boost your productivity is by improving your daily systems for completing tasks. Here’s a list of productivity techniques that have seemed most useful to the people we’ve worked with. Not all of them have as much direct empirical evidence as implementation intentions, but they’re quick to test for yourself, and they make sense — they mostly aim to help you prioritise and focus better. Try one each week, find the ones that help you the most, and then take several weeks to ingrain new habits. All of these are worth trying and can make a significant difference:

- Set up a system to track your tasks, especially small tasks. Getting Things Done is the most well-known book about task management, but it tends to be too involved for most people. An adaptation — “GTD in 15 minutes” — is much simpler and better for most of our readers. It’s usually worth getting some simple task management software, such as Asana or Todoist, to help with tracking.

Do a five-minute review at the end of each day. You can put all kinds of other useful habits into this review, such as gratitude journaling, tracking your happiness, and thinking about what you learned each day. As a bonus: try sending your to-do list for the next day to a friend or colleague. Just telling someone else is enough to give some motivation — even if there’s no formal accountability.

Start your day with your most important task, named “eating a frog” by a book of the same title. Get that one crucial thing you know you are avoiding done before you do anything else.

Do a weekly review. Every one or two weeks, take an hour to review your key goals, and plan out the rest of the week (and do the same quarterly). Here’s an example.

Batch your time. Group similar types of activities in regular time windows. For example, try to have all your meetings fall on one or two specific days of the week, then block out solid stretches of time for focused work. Rather than constantly checking your email, clear it once or twice a week. This approach reduces the costs of task-switching, and helps line up how you spend your time with what matters. Paul Graham discusses this in his essay, “Maker’s schedule, manager’s schedule.” A big-picture version of this is to set fixed work hours; for example, have a hard limit of stopping work by 6:00 PM. Many people have found this makes them more productive during their work hours while also reducing the chance of burning out and neglecting their social life.

Block social media. It’s designed to be addictive, so it can ruin your focus. Changing tasks a lot makes you less productive due to attention residue. For this reason, many people have found tools that block social media during work hours, or for a certain amount of time each day, to majorly boost their productivity. Some of the team’s favourite tools include Freedom and AppBlock for blocking specific sites and apps at particular times, and News Feed Eradicator for removing the news feed from social media sites. Here’s a more detailed guide.

Build a regular daily routine you enjoy. You can use your routine to build habits automatically — for example, always exercise first thing after lunch. Many people find having a good morning routine is especially important, because it gets you off to a good start.

Look for ways to avoid thinking about repetitive tasks to free up your attention, like eating the same thing for breakfast every day, or hiring a cleaner.

Be more focused by using the pomodoro technique. Whenever you need to work on a task, set a timer, and only focus on that task for 25 minutes. It’s hard to imagine a simpler technique, but many people find it helps them to overcome procrastination and be more focused, making a major difference in how much they can get done each day. Professor Barbara Oakley recommends it in her course, Learning how to learn. Another step would be to do this with someone else: tell each other what you’re each going to do in the 25-minute focus time, and then hold each other accountable at the end. Focusmate is a helpful platform for finding people to co-work with.

Track your time with tools like Toggl, HourStack, or a spreadsheet. This lets you check that your hours line up with your priorities, and helps you make better estimates of how long different tasks will take.

Further reading on productivity

A huge amount has been written about personal productivity. Hopefully, this list gives you an idea of what’s out there and some ways to get started. If you’d like more ideas, here are some systems and over-the-top reflections from highly productive people:

- Deep Work by Cal Newport. Also see our podcast episode.

- Seeking the productive life by Stephen Wolfram

- How I am productive by Peter Wildeford

- Productivity by Sam Altman

If you’re having trouble getting going with the rest of the list, the techniques in this section can help. Want to socialise more? Use a commitment device. Want to be more focused when you study? Batch your time. Want to take up gratitude journaling? Add it to your daily review. When you’ve spent a few months incorporating some of these habits into your routines, move on to the next step.

6. Get better at using the latest AI tools

As I write this, AI is already a bit like a team of expert advisors available 24/7 to help with any topic. I’ve heard reports of people who found it a struggle to get through a coding course before now speeding through in weeks because they can get instant help debugging, and they can ask AI to explain a concept in ten different ways until they find one that sticks. You can use AI as a tutor, editor, critic, or source of ideas and personalised advice on any topic — even things like what to do if you have cancer.

As AI continues to improve, it’s likely to become more and more like a true team of ‘digital workers,’ and effectively directing these workers will become one of the most valuable skills for any job.

“Learn to use AI” is already a bit of a cliché, but it’s still rarely done well. Indeed, some universities even ban their students from using it. First, make sure you pay to use the latest models, since these are usually significantly more capable than the free ones. Through 2025, critics continued to make fun of AI for not being able to count how many ‘r’s there are in the word ‘strawberry.’ But this wasn’t a problem for o1, which was released in September 2024 but only available if you paid $20 a month. They were mocking AI for a limitation it had already overcome.

Second, get in the habit of running your problems past your virtual team of advisors. Then check their answers. Over time, you’ll build a sense of what work different models can and can’t do. Using AI effectively means learning how to get it to challenge your thinking and fill in the gaps in your knowledge rather than just flatter you.

One tip is that AI typically generates far better results if you provide it with lots of context and 2–5 clear examples of the kind of output you want. But most people don’t do this; they just write a few sentences — far less context than you’d give a human — and hope it works out.

In GPT and Claude, you can create projects for different types of tasks, and you can preload context and custom instructions for each. For example, when I ask AI to edit some writing, I have a project loaded up with my best examples of that type of writing and instructions to avoid hyperbolic language or lists of common cliches. You can also provide context with long rambling voice notes, which AI itself can summarise into clear project instructions.

Over time, look for bigger chunks of more routine work you can automate wholesale. AI is best at tasks that involve manipulating data that exists on the internet, or answering math, coding, or science questions with known answers, but the scope of tasks it can do is expanding rapidly. It pays to keep an eye on what might become possible in the next one or two generations of models.

There’s much more to say about building AI-driven applications that automate large chunks of work while catching errors. We’d recommend listening to The Cognitive Revolution by Nathan Labenz to hear about the latest examples.

See more tips in our article “To understand AI, you should use it.”

7. Improve your basic social skills

It’s surprising how little good advice there is on how to improve social skills, given they’re important for almost everything in life. Social skills mediate our relationships, which are crucial for both our work and happiness.

That said, there are some basic things that anyone can learn that can make a big difference. Improving habits, learning how to make small talk, or simply changing how you think about social situations can make it much easier to make friends, get on with colleagues, and generally deal with other people.

The most popular guide to learning basic social skills is probably How to Win Friends and Influence People by Dale Carnegie. It’s full of advice like “A person’s name is to that person, the sweetest, most important sound in any language,” which you might want to take with a pinch of salt. And yet the book is classic for a reason. Bryan Caplan’s notes on the book are a nice summary and steelman. A more modern alternative some of our staff liked is Succeed Socially by Chris MacLeod, which is now available as a book.

If you’re looking to develop more advanced social skills, then you might find The Charisma Myth by Olivia Fox Cabane useful. It makes at least some attempt to use the limited research that exists. Other people have found things like improv and Toastmasters helpful.

Finally, much comes down to practice and getting comfortable talking to new people. So it’s useful to work on this area while also following the steps in the next section…

8. Surround yourself with great people

We talked about the importance of connections and community in the career guide. If you haven’t implemented that advice yet, now’s the time.

Eventually the goal is to have at least a couple of strong allies — both professionally and personally — who can advise you on difficult problems. In addition, aim to have a wider set of weak ties in the industries and scenes you’d most like to engage with, and to take part in one or two communities. Getting to that point takes time. Your network will grow naturally as your skills and accomplishments improve and you have more to offer.

For now, try implementing one or two regular habits that could introduce you to new people more often, such as running a useful social media feed or attending or hosting events. Develop some habits to follow up with people you’d like to stay in touch with, and look for ways to help them out. Test out being involved in a couple of communities.

In addition, there’s one other major change you can make to greatly improve your connections: changing where you live. Despite the rise of remote working, industries still cluster in certain places: Silicon Valley remains the place to be for software in the West; Boston is the best place for scientific research, including biotech; Taiwan is best for semiconductors; New York and London still dominate finance. In these places it’s much easier to build professional connections, to meet new people serendipitously, and to find out what they really think at the bar after work.

Globally, innovation is concentrated into under 20 mega-regions, which include the region between Paris, Amsterdam, and Munich; from Chicago to Pittsburgh; Greater Tokyo; Southern California; Seoul; the Texas Triangle; Beijing; Shanghai; and Shenzhen to Hong Kong.17 Economists believe this unusual productivity comes from the clustering of innovators into these regions, allowing for more rapid sharing of ideas, shared infrastructure, and perhaps the associated culture, suggesting that if you move, you’ll benefit too.18

Many of the people we’ve worked with saw their careers take off after they moved to a hub for the issues we most focus on, especially the San Francisco Bay Area, or Loxbridge (London, Oxford, Cambridge). Besides being in on the gossip, it’s more inspiring and energising being close to the action.

Moving can be especially good if you don’t feel a strong fit with the social life in your hometown. However, if you like your current location, it’s worth remembering that it takes a long time to build up a network of friends, and that you’ll probably have to leave behind relatives. Since close relationships are perhaps the most important ingredient of fulfillment, this is a big deal. Your location also drives your social life, your day-to-day physical environment, and even how much money you end up with in retirement. One survey of 20,000 people in the US found that satisfaction with their location was a major component of life satisfaction.19

So while moving can be a huge boost, we also know many who moved and then moved back. That includes me. After going through Y Combinator in 2015, the 80,000 Hours team moved to the Bay Area in 2016 in order to be part of the tech scene and because we thought it would be better for hiring. But in 2019, we moved back to London, in part due to dissatisfaction with our social lives. Other common reasons to move back are to be closer to your parents, especially when starting a family, or just to feel more at home.

If you’re interested in moving cities, first try out living there for a few months — and include a cooling-off period before moving. Another option would be to move for 1-3 years to make connections, and then move back. It’s also possible to get many of the benefits just by doing one or two longer visits to a hub per year. If you do make the move, keep in mind it could take several years to really settle in.

Best further reading on networking

- Chapter 4 of The Startup of You by the founder of LinkedIn, Reid Hoffman.

- Give and Take, by Professor Adam Grant, is about how the most successful people are those with a giving mindset, in part because it helps them to build more connections.

- Never Eat Alone by Keith Ferrazzi. The tone isn’t for everyone, but it shares the same approach as the above, and also has lots of tactical tips.

- How to become insanely well-connected is a classic article with great practical networking advice.

- How to make friends as an adult is a short essay in Barking Up the Wrong Tree.

- We also enjoyed Paul Graham’s essay about how different locations have different vibes.

9. Apply scientific research into happiness

Being happier is not only good in itself, it can also make you more productive, a better advocate for social change, and less likely to burn out.20 Researchers in the field of ‘positive psychology’ — the science of wellbeing that we introduced in our article on job satisfaction — have developed practical exercises to make you happier and tested them to see whether they really work. We think this is one of the better places to turn for self-help advice.

In part, this research re-emphasises the fundamentals we’ve already covered — sleep, exercise, family and friends, and mental health — but they’ve added some other techniques too. Below is a list of recommendations from Professor Martin Seligman, one of the founders of the field, most of which are taken from his book Flourish. In 2020, the largest meta-analysis of positive psychology interventions we’re aware of found positive effects for all the types of interventions listed.21 Test them out, and keep using them if they’re helpful.

- Start gratitude journaling. Write down three things you’re grateful for at the end of each day, and what caused them to happen. Other ways of cultivating gratitude are also good, like the gratitude visit.

Learn some basic cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). Even if you don’t have a mental health issue, CBT can be helpful for emotional management. A simple exercise is the ABC of CBT which you could do at the end of each day.

Use your signature strengths. Take the VIA Character Strengths survey, then make sure you use one of your top five strengths each day. Read more.

Craft your job. Often it’s possible to adapt your job so that it involves more of the satisfying ingredients identified earlier, like ‘flow’ states, or less of what you don’t enjoy. It could be as simple as trying to spend more time with a friend at work, or making the tangible effects of your work more obvious. Adam Grant found that having university fundraisers meet someone who had benefited from a scholarship made them dramatically more productive.22 And job crafting exercises more broadly seem to work.23 Here’s a practical introduction.

Do something kind each day, like donating to charity, giving someone a compliment, or helping someone at work. Random acts of kindness cause a significant boost to the mood of the giver.

Practise ‘active constructive responding.’ When someone tells you good news, make a point of responding enthusiastically and authentically, and ask to learn more.

Schedule something you enjoy each day and practice savouring it, whether that’s your morning coffee, some beautiful music, or a walk in nature.

Try meditating. There’s a significant amount of evidence from trials that meditation and other mindfulness practices help with wellbeing, stress, mental health, focus, empathy, and more. You can see a review of some of this literature in Altered Traits by Goleman and Davidson, as well as some large studies in the footnotes.24 You can also try to meditate for 20 minutes per day and see if you notice any benefits. The easiest way to try meditation is by using an app, such as Waking Up, The Way or Effortless Mindfulness. The book Mindfulness by Penman and Williams is also a great introduction, organised into an eight-week course similar to ‘mindfulness-based stress reduction,’ which has been shown to be effective for managing stress and improving quality of life in clinical trials.

If you’re up for something more adventurous, replace a holiday with a meditation retreat. Doing a large dose can give you a better indication of what benefits meditation might have for you (though also with more risk of negative effects — be sure to find a good teacher and stop practicing if it’s consistently making you feel worse). Personally, meditation is probably the thing that has most increased my wellbeing, but it also took around 1,000 hours of practice before I noticed persisting benefits, so I’d normally only recommend focusing on it after taking the low hanging fruit in the other parts of this article. If you’d like to try a retreat, I’d most recommend Jhourney, which was founded by an 80,000 Hours reader.

One other habit that can help with all of the above is to rate your happiness between 1 and 10 at the end of each day. Our memory of what makes us happy isn’t so reliable, but by rating your happiness you can build up a more objective picture of what works for you over time. Moodscope is a good tool.

To get more positive psychology exercises, check out the free courses on Clearer Thinking, and read The How of Happiness by Sonja Lyubomirsky.

10. Use these tips to save more money

We recommend people save until they have at least six months of ‘runway’ — the length of time you could comfortably live without income, whether by cutting spending or using savings. Ideally this should be 12, but it depends on how long it would take you to find another job. Besides the extra security, a long enough runway will give you the flexibility to consider big career changes, navigate turbulent times, and take risks.

In addition to your runway, the conventional advice is to work towards saving about 15% of your income for retirement.25 The possibility of AGI arriving in the next decade might actually increase the importance of saving money. If mass automation happens, your career might not last as long as you’d thought, investment returns could be very high for a period, and new technologies (and therefore new goods) might arrive sooner than expected.

So how can you go about saving money? To begin with, make it automatic. Set up a direct payment to flow directly from your main account to a savings account after you get paid so you never notice having the money in the first place.

Next, focus on big wins. Instead of constantly scrimping (don’t buy that latte!), identify one or two areas of your budget you could reduce that would have a big effect. In many cases cutting rent by moving somewhere smaller and cheaper, or sharing a house with someone else, is the best thing you can do to make large savings. Until you have six months of runway, cut your charitable donations back to 1%.

A different strategy is to move somewhere fun and cheap temporarily. This is easier than ever due to the rise of remote work. It’s still possible to rent a nice apartment with a pool for $500 per month in Chiang Mai.26

While doing the above, beware of swapping money for time. Suppose you could save $100 per month by moving somewhere more affordable — but you’d be adding an hour to your commute. Instead, maybe you could spend that time working, making you more likely to get promoted or earn extra wages. You’d only need to earn an extra $5 an hour to break even. It might also be more effective to focus on earning more than spending less, especially by negotiating your salary. This tool can help you quantify the value of your time in dollars.

For more advice on how to save money, many of our readers have found the financial independence retire early (FIRE) community and the blog Mr. Money Mustache helpful. For more reading on personal finance for people who want to donate to charity, see this introductory guide and this advanced guide.

11. Use research into decision-making to think better

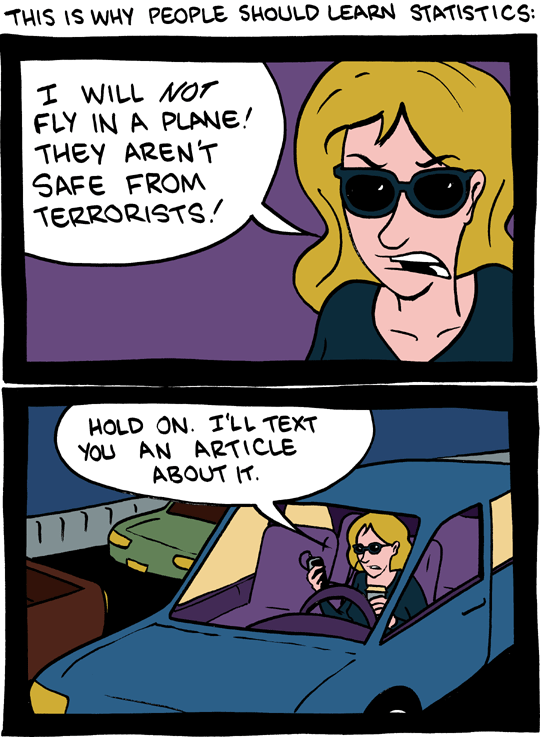

Why do so many smart people make so many dumb decisions? Research suggests intelligence and rationality are distinct. You can be great at solving narrow problems, but bad at making decisions in real-life situations. Fortunately, the same research has shown that of the two, rationality is easier to train.27

Having more accurate beliefs and making good decisions are two of the most important meta-skills, because they’re what you use to figure out everything else. They’re even more important if you want to have a positive impact on the world: it’s hard to know which ways of helping are actually best, and all strategies will involve some judgement calls, but at the same time, there are huge differences in the impact of different paths. That means the more reliable your judgement, the more likely you are to find the most impactful options. So how can you improve it?

Beyond our discussion of what cognitive psychology has learned about improving decision-making, here’s another line of fascinating research by Philip Tetlock28, a professor of psychology. For years, Tetlock tracked the predictions pundits made in the media about current events, such as who would win elections, or whether Russia would invade Ukraine. He found that most pundits couldn’t predict these kinds of events better than chance. However, he identified a minority who were much better than average. He dubbed those individuals ‘superforecasters.’

Tetlock identified the traits that make someone a good forecaster, then developed a training programme to teach others those skills. He tested the training programme to prove it made people measurably better at making forecasts. So what did he learn? Broadly, getting better judgement is a matter of having the right mindset, building the right habits of thinking, and practice.

On mindset, Tetlock concluded that the people with the best judgement tended to have a ‘fox’ thinking style: they considered many different points of view, were cautious and humble about what they knew, and saw their beliefs as hypotheses to test. In contrast, many pundits were ‘hedgehogs’: they had a single worldview and applied it to every question. To start developing this mindset, we’d recommend the book Scout Mindset by Julia Galef.29

Being aware of the many biases that compromise our thinking can be helpful, but research has also shown awareness alone is not sufficient30 — we need better habits of thinking. Tetlock also found that the best forecasters would typically break questions down into smaller, easier ones. They would often start with a ‘base rate’ forecast (based on what’s happened most often in the past), and then adjust from there by considering what was unique about the situation.31 Rather than restrict themselves to ‘rigorous’ evidence like scientific studies, they’d consider any kind of evidence, but they’d weigh it by its strength.

They’d also consider the question from many angles and find an average across the different perspectives. For example, if one expert believes a risk is 90% likely, while another believes it’s 1% likely, the best forecasters would go for somewhere in the middle, depending on how much they trusted each opinion. To consider many perspectives, it helps to be a generalist: to have a little knowledge about a wide range of fields. Former 80,000 Hours staff member Peter McIntyre created a list of key concepts, which you can receive via a weekly email. It’s particularly important to understand basic statistics and decision analysis, since the best forecasters often think quantitatively. A great book about how to take a rational approach to messy problems is How to Measure Anything by Douglas Hubbard.

Finally, and most importantly, is practice. Most people are overconfident about their predictions. If they say it is 80% likely that the answer to a question falls within a specific range, they’re only correct about half to two-thirds of the time.32 However, studies have found that just an hour of ‘calibration training’ can significantly reduce this problem.33 You can do this with an online tool, such as Coefficient Giving’s Calibration quiz.

To further improve, make predictions relevant to your own life, and track them using Fate Book. Or try participating in a forecasting competition or platform, like Metaculus, which will let you measure your accuracy over time. We also have a longer article about improving your judgement.

Forecasting and decision-making are just one aspect of the broader project of thinking well, but they’re especially useful because they’re measurable. Personally, when I need to think more clearly about a topic, I find the most useful technique is to write about it. GiveWell and Open Philanthropy founder, Holden Karnofsky, has written a guide to learning through writing.

12. Learn how to learn

Many people have spent thousands of hours driving, but that doesn’t make them expert drivers. Why not? One explanation comes from K. Anders Ericsson, whose research on expertise we introduced in our article on career capital. Ericsson argues that expertise depends not so much on how many hours a person has spent doing a task, but how many hours they’ve spent doing deliberate practice,34 which can be characterised according to the following four factors:

- Specific goals focused on improving your weaknesses and trying new techniques

- Intense focus on the task that feels both effortful and a little uncomfortable

- Rapid feedback on how well you’re performing

- A good coach or teacher

- Progressively increasing difficulty of tasks

On a typical drive to the supermarket, none of these ingredients are present, which is why you don’t get better at driving. Becoming an expert driver requires putting yourself into increasingly challenging situations that stretch your abilities. The same turns out to be true for work. In our article on personal fit, we saw that the correlation between years of experience and job performance is very weak. One explanation is that people rapidly improve in their first couple of years while they’re being stretched, but eventually they can basically do the job, and their skills stop progressing.35

Ericsson’s research is summarised in his fascinating (if polemical) book, Peak. While many researchers in the field think his claims about practice being the sole determinant of expertise are overstated, pretty much everyone agrees that deliberate practice is very useful for gaining skills. This suggests that rather than just carrying out your work in the normal way, you can learn a lot faster by seeking out the above five conditions.

It’s often hard to hit all of the five criteria in real-life situations, but you can still modify your normal work to get a bit closer. This approach has been called deliberate performance.36 Here are a couple of exercises from the literature:

- Experimentation: Rather than carrying out your work the same way every time, try out different techniques. For example, if you want to improve your public speaking, get advice on common techniques and try one each time you give a talk.

Debugging: When you encounter a problem (or even just a near-miss) try to come up with an explanation of what went wrong, or ask an expert. For instance, after giving a talk, ask your boss about why the audience seemed to lose interest on a particular slide.

Estimation: Estimate how long different tasks will take, and check your accuracy. For example, how long will it take you to write the script for a talk? How long will it take to deliver the introduction? This helps to improve your mental models of how the activity works.

Deliberate practice and performance are easiest in more predictable domains where standardised training techniques exist, such as in chess or sports. In less predictable fields, like disaster response or business strategy, every situation is different, which means there’s less correlation between practice and performance.37 However, even in these fields, experts can build better intuitive, tacit knowledge of how to do the task. What’s crucial in either case is spending time with experts in the field and seeing lots of real cases. If you’re not able to find an expert mentor, you can ask AI to act as a tutor and get some of the benefits.

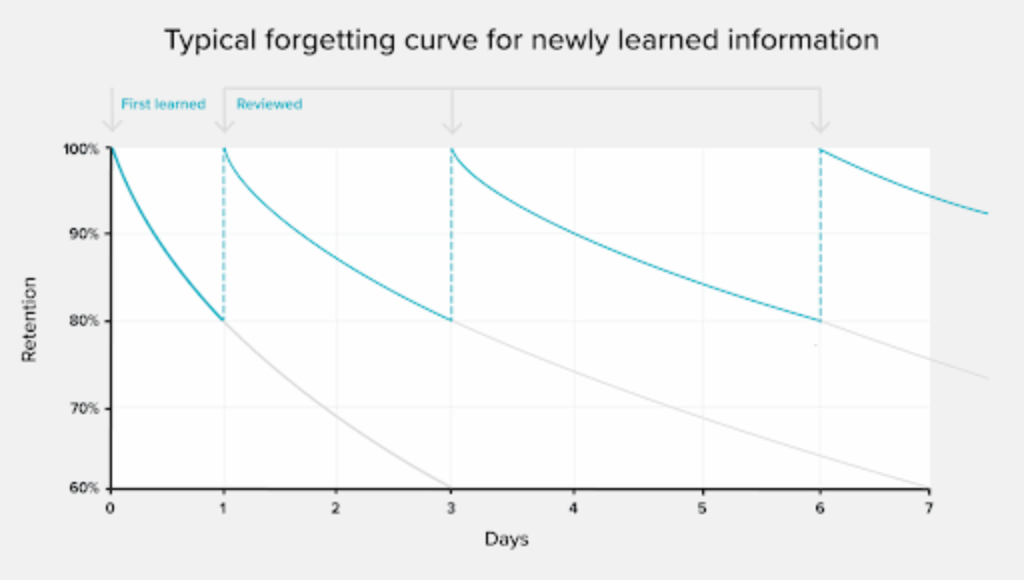

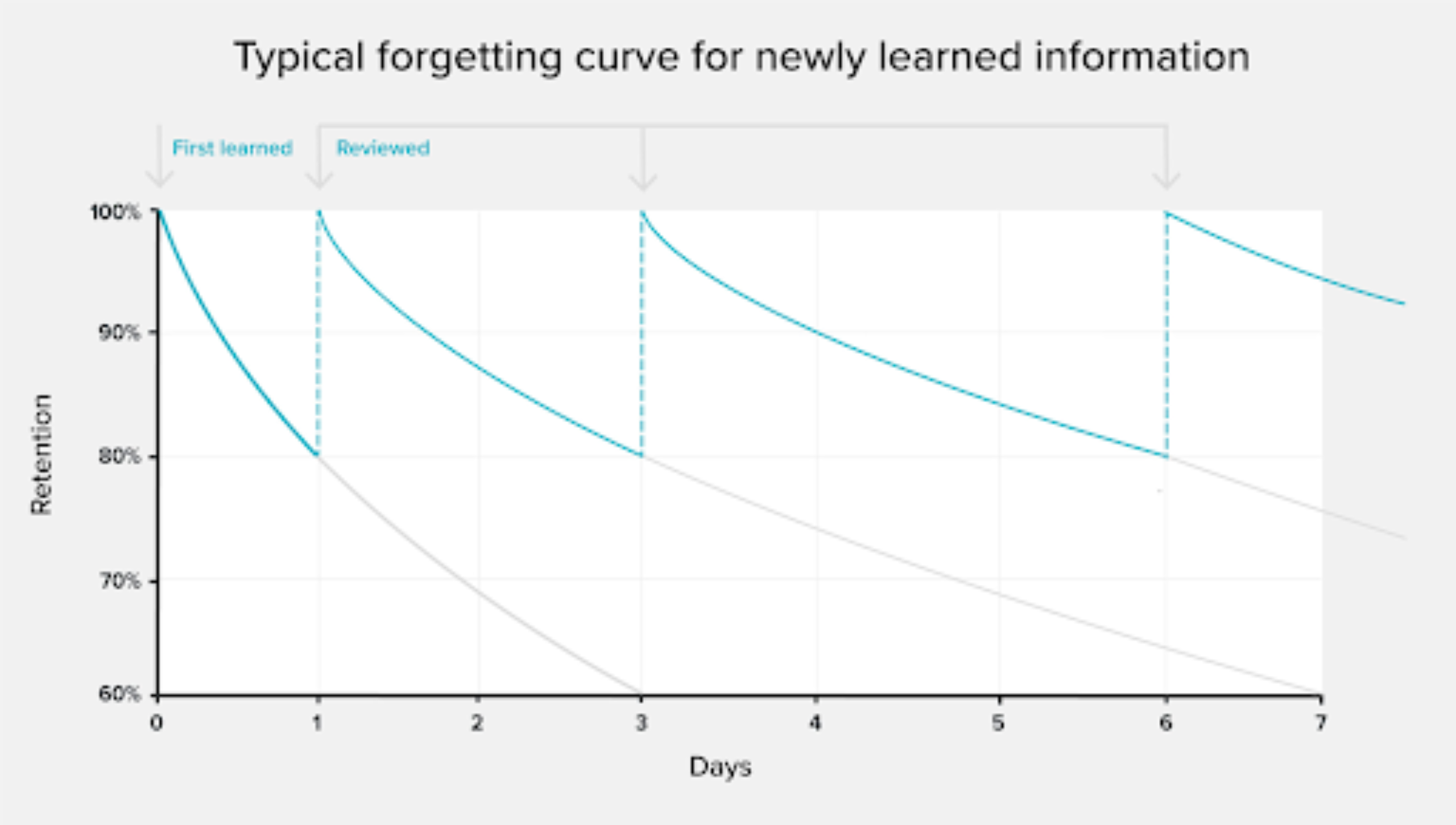

There are other ways to learn much faster than the normal defaults, such as spaced repetition. If you’re trying to memorise something, like a word in a foreign language, research shows that there’s an optimal frequency to review the word. If you use this frequency, you’ll be able to memorise much faster. There are tools that can help you with this, like Anki, which lets you make your own flashcards.

For more study techniques, our top recommendation is the Learning How to Learn course on Coursera by Professor Barbara Oakley, which is among the most viewed online courses of all time. You could also read the book it’s based on, A Mind for Numbers.

Learning rapidly is another area where the 80/20 principle applies. When I was working through a Chinese textbook at a university in Beijing, I found all kinds of random topics (one day we studied the special interior decoration of the train to Tibet). But the top 1000 Chinese words account for about three quarters of daily usage, so it’s better to learn the most common words first. I was a bit obsessive about Chinese food, so even more useful (for me at least) was studying the words that were most likely to appear on menus. More broadly, I wanted to be able to travel and chat in Chinese, so deliberate practice in my case meant actually speaking Chinese out loud rather than studying in a classroom.

13. Be strategic about how you use your time at work

Just as some of your goals will produce much bigger results than others, and some things you could learn will have far more application than others, it’s probably the case that in your job, a minority of tasks will do far more to determine your success than others.

A salesperson is judged by the revenue they bring in, an academic by the number of quality papers they publish, and a YouTuber by their view counts. This means you can often advance a lot faster and have more impact by identifying and focusing on the tasks that drive those key results. An entrepreneur who builds their product and gets feedback from real users will make more progress than one who does lots of conferences and media, even if the second works longer hours. Working harder helps, especially in ‘winner-takes-all’ situations, but you should only work harder after first taking all of the steps available to work smarter.

In order to figure out which activities are crucial to focus on, talk to people who have succeeded in your chosen path. Don’t just trust what they tell you — work out what they actually did to get ahead. Once you’ve identified all of these activities, use the advice from the sections on productivity and learning how to learn to get them done as well as possible.

The advice above applies to situations where your impact comes directly from carrying out your work, or when you’re trying to build your career capital in a path, but what about situations where your impact is more indirect?

Imagine you work in government. There will be hundreds of policy ideas you could work on, but for all of the reasons we’ve seen in the guide, some of these will probably be massively more impactful than others. What your boss wants you to work on, however, may not line up with the policies you think are most impactful. This suggests the following strategy: spend most of your time focused on doing whatever your boss (or other seniors) cares about most, but with 20% of your time, make a bid to work on what you think will be most impactful. Doing what your boss wants advances your career and gives you the workplace capital needed to make requests later, but if that 20% is well-targeted, you can still have an outsized impact, perhaps even achieving the majority of what you could have achieved with 100% of your time.

A similar dynamic often applies in media careers, like journalism. The demands of the market mean that most of the stories you write won’t be on the topics you think are most important. But succeeding conventionally can enable you to spend 20% of your time writing about genuinely novel and neglected stories.

Further reading: check out the Top Performer course by Cal Newport and Scott Young, as well as their other writing, including So Good They Can’t Ignore You, “Why most people get stuck in their careers,” and “Four principles for decoding career success in your field.”

14. Become an expert

Once you’ve worked on the basics, become more productive, learned how to learn, and figured out where to focus in your job, an endgame would be becoming an expert in a valuable skill and using that expertise to tackle a meaningful problem. While most of the steps above are things you might focus on for a few months or a year, this is a life-long task.

So how should you choose what expertise to focus on? First, if you’re going to put a decade plus of work into something, you’ll want to pick an area of expertise that’s valuable. Hopefully our advice on valuable skills gives you some ideas for this.

I don’t necessarily mean becoming a specialist in a single narrow topic. Our article talks about which combinations of skills are valuable, and you can also become an expert in being a generalist. Many roles, such as those involved in running organisations, require people who are well-rounded and understand each part of the organisation. As a researcher, knowing about several fields can help you spot new ideas. Communicators, grantmakers, and policy makers also often need medium-depth knowledge of a wide range of areas in order to spot the best ideas.

Second, you’ll want to choose an area where you have a reasonable shot at actually attaining expertise. We saw in the career capital article that this requires a mixture of:

- Personal fit

- Deliberate practice

- Good timing

It’s unlikely that you can fully predict this ahead of time, so you will need to try out different areas and see what works. Once you’re on a path, try to set up the best possible conditions for practice, as covered in section 12, including mentorship and rapid feedback. Then practice as much as you can.

One thing that sets true experts apart is their ability to make creative contributions. We’d love for there to be better recommendations on this topic, but here are two books where you can learn more:

- Originals by Professor Adam Grant

- Wired to Create by Scott Barry Kaufman and Carolyn Gregoire

15. Become a better person

Nothing listed here is worth much unless you use it for good ends. But it’s not always easy to act virtuously.

Becoming a better person means getting clearer about what you value and trying to live your life more in line with those values. In the section on setting goals, we introduced some ways to reflect on what your ideal life looks like, but don’t limit yourself to self-reflection. People have thought about these questions for millennia, and it’s worthwhile to learn about these ideas at some point. This means being familiar with basic moral philosophy. Being Good by Simon Blackburn is a good introduction. You may also want to explore some of the major spiritual traditions.

While our career guide focuses primarily on the question of what ends to strive for, most spiritual and moral traditions place great emphasis on another part of leading a good life: the development of character. By this I mean the habits of behaviour that support a flourishing life, such as kindness, courage, curiosity, humility, respect of important norms, and integrity. In the early 2000s, a group of psychologists set out to study the character strengths that were valued by different moral traditions and found that many converged on the same ones. They made a list of 24 key character strengths, which they grouped into wisdom, courage, humanity, justice, temperance, and transcendence.

Many of these strengths help us overcome the human tendency to do what’s easy in the short run at the expense of what’s best in the long run. Asking your boss for feedback could save you a lot of time, but requires enough courage and humility to overcome the short-term sting of finding out you’re not doing as well as you thought.

But rather than being courageous a single time, you could make courage part of your character, turning it into a habit and a part of your identity that becomes deep-rooted and automatic.

In the book The Road to Character, David Brooks explores how character was pivotal in the success of historical figures, such as George Marshall, whose exceptional trustworthiness enabled him to end up coordinating a large part of the Allied War effort in WW2.

These character virtues are also vital for working with others. If you get a reputation for dishonesty, it will harm your impact because people won’t trust you. And if you’re part of a community, the consequences could be far worse: you might undermine trust within that community and damage its reputation with outsiders.38

There’s a significant literature in game theory and evolutionary psychology showing that cooperative behaviours can benefit both the individual and the group. In the 1980s, the political scientist Robert Axelrod designed a competition where contestants would play repeated games of ‘prisoner’s dilemma’ against each other. This is a game where you can either choose to cooperate or defect. It’s designed so that from an individual perspective, the best option is to defect, but if both parties overcome that to cooperate, they can achieve an even better joint outcome.

Each entrant to the competition wrote an algorithm for how their player would respond to other players. Axelrod shows that the strategies that did best were those that tried to cooperate first, but had a backup plan: if someone defected against them, they’d give the defector one chance to change their ways before they’d defect back. In other words, be kind to strangers, be forgiving, but don’t tolerate those who try to exploit you.39 These strategies not only enabled each individual to maximise their score, but also made it easy for others to maximise their own. (I explore this more in our article on coordination.)

Cultivating character is especially important if you’re going to seek influential positions to maximise your impact. The more influence you get, the more tempted you’ll be to do something unethical in order to preserve your power. Resisting this temptation when it most matters requires you to build up your character when the temptations are less intense.

Many moral traditions claim that upholding positive character traits is inherently good, whether or not it leads to better consequences. But even utilitarian philosophers — who argue all that matters in the final accounting is how much you help others — have long argued that behaving virtuously tends to lead to better outcomes. You can find a modern version of this argument in “Virtues for real world utilitarians.”40

So how can you build character? This brings us back to where we started. At their simplest, character traits are habits that have become so ingrained as to become automatic. That means you can build them in the same way you’d build other habits. For instance, to develop an honest character, practice being more honest in small stakes situations each day and by surrounding yourself with unusually honest people.

It can help to be part of a community with an explicitly moral focus. I’ve been involved in effective altruism, but also in secular Buddhist communities. You can explore whether that’s of interest in Buddhism and Modern Psychology by Robert Wright and Waking Up by Sam Harris. The book Altered Traits also explores the evidence that certain meditation practices can increase compassion and your ability to act virtuously.

Emotional triggers may also prevent you from being your best self, so you may want to return to the section on mental health. But this time the aim isn’t only to address a specific mental health issue, but rather to reduce how often you get emotionally triggered, and how well you’re able to deal with it when you are. Therapies in the tradition of CBT have several tools for this, including exposure therapy to triggering situations and memories (which reduces how much they activate), examining unconstructive beliefs behind your triggers, developing better awareness of your emotions, building habits that help you self-regulate, and strengthening your communication skills. Two resources aimed at helping successful people develop these kinds of skills are The 15 Commitments of Conscious Leadership (which I’ve found helpful, though I don’t agree with all their advice), and the Art of Accomplishment (which has been recommended to me by several people).

One exercise is to pick one character strength or emotional management habit each quarter to focus on building. But occasionally, really challenge yourself: change jobs to help others, give more, or take a stand for an unpopular issue. Try setting yourself one big moral challenge each year.

The compounding benefits of investing in yourself

People keep improving their skills for decades. So even if you’re not in the ideal job right now, know there’s still a huge amount you can do to make yourself happier, more productive, and better placed to have a positive impact on the world. These won’t always be overnight fixes, but you’ll be surprised by how quickly small adjustments snowball to produce dramatic effects.

Knowledge and productivity are like compound interest. Given two people of approximately the same ability and one person who works 10% more than the other, the latter will more than twice outproduce the former. The more you know, the more you learn; the more you learn, the more you can do; the more you can do, the more the opportunity.

Richard Hamming, You and Your Research

If you apply the material on productivity and learning how to learn, you can learn everything else on the list. Apply the material on positive psychology and you’ll be happier, which helps you be more productive. If you surround yourself with supportive people, that helps with everything else too. In this way, over the years, you can grow far beyond where you are today and achieve much more than you might first think. So pick an area and get started.

Put into practice

- Of the 15 areas in this article, which one seems most useful for you to focus on right now?

- What are 1–3 small ways you could improve in that area? When and where will you do them?

- When will you next review what personal development topic to focus on?

Take a break by learning about how we turned this advice into our daily routine.

Read next: Part 14: How to make your career plan

Or see an overview of the whole career guide.

Notes and references

- This research is covered in the book Rethinking Positive Thinking by Gabriele Oettingen, published 10 November 2015. You can see a popular summary in The New York Times. Oettingen actually finds that also thinking about how you’re most likely to fail makes you more likely to achieve your goals, so in a sense negative thinking is more effective in this context. However, there are other senses in which positive thinking is helpful. CBT, as we cover in this article, is based on the idea that many mental health problems are caused by unhelpful beliefs, which can be changed by disputing them and by other techniques. So ‘positive thinking’ can work, but it depends on exactly what you mean and what the context is.↩

- In two experiments, participants with low self-esteem who repeated the statement “I’m a lovable person” or focused on ways it was true felt worse than those who didn’t repeat the statement, likely because the affirmations highlighted the gap between their self-view and the positive standard.

Wood, Joanne V., et al. “Positive self-statements: power for some, peril for others.” Psychological Science, vol. 20, no. 7, July 2009, pp. 860–866, www.uni-muenster.de/imperia/md/content/psyifp/aeechterhoff/wintersemester2011-12/seminarthemenfelderdersozialpsychologie/04_wood_etal_selfstatements_psychscience2009.pdf.↩

- A bit more precisely, we tried to rank steps based on an all-considered view of (i) the strength of the empirical evidence, (ii) whether it makes theoretical sense, (iii) how much potential upside there is from applying the advice, (iv) how widely applicable it is, and (v) the costs of applying and testing an idea.↩

But there’s this other group of givers that I call ‘otherish.’ They are concerned about benefiting others, but they also keep their own interests in the rearview mirror. They will look for ways to help others that are either low cost to themselves or even high benefit to themselves, i.e., ‘win-win,’ as opposed to win-lose. Here’s the irony: The selfless givers might be more altruistic, in principle, because they are constantly elevating other people’s interests ahead of their own. But my data, and research by lots of others, show that they’re actually less generous because they run out of energy, time, and resources — basically, because they don’t take enough care of themselves. The ‘otherish’ givers are able to sustain their giving by looking for ways that giving can hurt them less or benefit them more.

From an interview with Adam Grant, by Wharton, where he summarises his research. Archived link, retrieved 6 April 2017.

You can find more detail in his book Give and Take, published 25 March 2014.↩

- We think it’s common sense that health, diet, exercise, and relationships all matter a great deal to day-to-day happiness. We’ve also reviewed the literature on positive psychology here and think the evidence is in favour of this idea (especially the importance of close relationships), or at least doesn’t contradict it. There is also research specifically about the impact of sleep on mood.

Note that we haven’t seen good direct evidence that a healthy diet improves mood, but we find it hard to believe that it doesn’t improve health and energy, which will improve mood over the long term.↩

- The chapter on nutrition in Outlive by Dr Peter Attia has a good summary of the state of the evidence and how little is known about optimal nutrition.

Attia, Peter, and Bill Gifford. Outlive: The Science & Art of Longevity. Vermilion, 2023.On the point about protein in particular, typical government guidelines recommend 0.7–0.8 g per kg of bodyweight, which would be around 55 g per day for men and 45 g per day for women, an amount almost everyone in high-income countries hits. However, many studies have found that eating significantly larger amounts (e.g. up to more like 2 g per 1 kg of bodyweight) continues to have benefits in terms of muscle gain if you exercise. Having more muscle is (all else equal) generally healthier because it reduces frailty from aging, and strength is a strong predictor of longevity. People with more muscle also report more energy and confidence.↩

- Different surveys give different results, but 30% seems like a reasonable ballpark. For instance, the US National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) says that 30.6% of 18- to 25-year-olds and 25.3% of 26- to 49-year-olds have “any mental illness.”

Archived link, retrieved 28 February 2023.

The NIMH also finds that 17% of people aged 18–25 experienced a major depressive incident in the last 12 months, compared to only 5.4% for those above 50.

Archived link, retrieved 8 March 2023.↩

- CBT is widely considered by experts to be among the most evidence-based forms of therapy. Here is one meta-analysis showing positive effects across a wide variety of conditions: Fordham, Beth, et al. “The evidence for cognitive behavioural therapy in any condition, population or context: A meta-review of systematic reviews and panoramic meta-analysis.” Psychological Medicine, vol. 51, no. 1, Jan. 2021, pp. 21–29, https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291720005292.↩

- Burns, David D. “Episode 192: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and beyond (with David Burns).” Clearer Thinking with Spencer Greenberg. 11 January, 2024. podcast.clearerthinking.org/episode/192/david-burns-cognitive-behavioral-therapy-and-beyond

Burns, David D. “Episode 255: The heavy price you’ll pay to have a healthy relationship (with David Burns).” Clearer Thinking with Spencer Greenberg. 29 March, 2025. podcast.clearerthinking.org/episode/255/david-burns-the-heavy-price-you-ll-have-to-pay-to-have-a-healthy-relationship/↩

- The idea that therapeutic alliance — essentially the quality of relationship with the therapist — matters more than specific techniques comes from research on ‘common factors’ in psychotherapy. The most influential statement of this finding was a 1975 meta-analysis concluding that different evidence-based psychotherapies produced roughly equivalent outcomes — the “dodo bird verdict.” Luborsky, Lester, Barton Singer, and Lise Luborsky. “Comparative Studies of Psychotherapies: Is It True That ‘Everyone Has Won and All Must Have Prizes’?” Archives of General Psychiatry, vol. 32, no. 8, 1975, pp. 995-1008.

This has been supported by subsequent research, including Wampold, Bruce E., et al. “A Meta-Analysis of Outcome Studies Comparing Bona Fide Psychotherapies: Empirically, ‘All Must Have Prizes.'” Psychological Bulletin, vol. 122, no. 3, 1997, pp. 203-215.

More recent research suggests specific techniques do work better for certain conditions — for example, CBT appears advantageous for anxiety disorders — but therapeutic alliance remains a vital factor.

Tolin, David F. “Is Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy More Effective than Other Therapies? A Meta-Analytic Review.” Clinical Psychology Review, vol. 30, no. 6, 2010, pp. 710-720.↩ - A 2025 systematic review in Nature compared generative AI to physicians and found similar accuracy.

Analysis of 83 studies revealed an overall diagnostic accuracy of 52.1%. No significant performance difference was found between AI models and physicians overall (p = 0.10) or non-expert physicians (p = 0.93). However, AI models performed significantly worse than expert physicians (p = 0.007).

Takita, Hirotaka, et al. “Diagnostic performance comparison between generative AI and physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” medRxiv, 22 Jan. 2024, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2024.01.20.24301563v2. (2024): 2024-01.↩

- HIV disproportionately affects people in developing countries:

“Global Statistics.” HIV.gov. 5 September, 2025, archive.ph/AbQBr. (Archived link retrieved 6-Sep-2025.)

Coronary heart disease is most common among people with particular risk factors:

National Health Services. “Coronary Heart Disease: Causes.” Health A to Z, 17 January, 2024, archive.ph/FeUob. (Archived link retrieved 6-Sep-2025.)

A major study published in The Lancet found the top five causes of ill health (measured by percentage of disability-adjusted life years) among 25- to 49-year-olds were:- Road injuries (5.1%)

- HIV/AIDS (4.8%)

- Ischaemic heart disease (4.7%)

- Low back pain (3.9%)

- Headache disorders (3.7%)

See Figure 2, “Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019,” Link.

According to the US government:

The vast majority of people with HIV are in low- and middle-income countries. In 2021, there were 20.6 million people with HIV (53%) in eastern and southern Africa, 5 million (13%) in western and central Africa, 6 million (15%) in Asia and the Pacific, and 2.3 million (5%) in Western and Central Europe and North America.

And according to the NHS:

Coronary heart disease (CHD) is usually caused by a build-up of fatty deposits (atheroma) on the walls of the arteries around the heart (coronary arteries). The build-up of atheroma makes the arteries narrower, restricting the flow of blood to the heart muscle. This process is called atherosclerosis. Your risk of developing atherosclerosis is significantly increased if you smoke, have high blood pressure (hypertension), have high cholesterol, have high levels of lipoprotein (a), do not exercise regularly, or have diabetes.

While, for back pain, according to the NHS:

Back pain can have many causes. It’s not always obvious what causes it, and it often gets better on its own.

This suggests that if you aren’t hit by a vehicle, don’t live in a developing country, and don’t have any of the major factors associated with ischaemic heart disease, the biggest risk to your health during your working life is low back pain.↩

- You can get clearer about your values by asking yourself why you’re pursuing any goals you have over and over until you can’t think of any deeper reasons. When doing this, it’s useful to keep in mind the ingredients that are most important for fulfilment from part 1: satisfying relationships; a mission beyond yourself; a sense of ‘craft’; some fun and positive emotion; and a lack of major negatives (like financial stress, health problems, or interpersonal conflict). To put it bluntly: health, relationships and your mission, in that order.↩

- More specifically, you should probably order your goals in terms of value produced per hour. Read more justification for this in the book Algorithms to Live By.↩

Holding a strong goal intention (“I intend to reach Z!”) does not guarantee goal achievement, because people may fail to deal effectively with self‐regulatory problems during goal striving. This review analyzes whether realization of goal intentions is facilitated by forming an implementation intention that spells out the when, where, and how of goal striving in advance (“If situation Y is encountered, then I will initiate goal‐directed behavior X!”). Findings from 94 independent tests showed that implementation intentions had a positive effect of medium‐to‐large magnitude (d = .65) on goal attainment.