We think AI poses the world’s most pressing problems. Here’s why.

Table of Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Summary

- 3 Why we think advanced AI poses the world’s most pressing problems

- 3.1 1. AI could replace human labour in the most economically valuable fields

- 3.2 2. Replacing this much human labour could trigger the next radical transformation of society

- 3.3 3. This transformation could be extremely rapid and dramatic

- 3.4 4. A rapid, AI-driven transformation would raise a range of major challenges, including existential risks

- 3.5 5. Work on these problems is tractable but neglected

- 4 Objections and replies

- 5 What’s next?

- 6 Learn more

- 7 Acknowledgements

Introduction

Imagine you’re living 15,000 years ago. Your people are hunter-gatherers and you sleep under the stars. If someone told you humans would one day build cities with millions of people, fly through the air, or carry all human knowledge in their pockets, you couldn’t even begin to picture what they meant.

Yet here we are.

How did our lives change so far beyond recognition? The story is complex, but there’s a rough pattern. A few times in history, some radical breakthrough in technology — like the development of the plough and the steam engine — has led to a wave of productivity, innovation, and social change that ultimately reshaped the world.

Now we’re on the cusp of a huge new breakthrough: artificial intelligence that can meet or exceed human capabilities across a wide range of tasks.

This could bring another era of transformation. There could be an explosion of intelligence and innovation, and a whole new population of digital beings. And with this, civilisation could see changes at least as profound as those brought about by industrialisation or the rise of agriculture.

But unlike the Industrial and Agricultural Revolutions, a transformation driven by advanced AI might not take hundreds or thousands of years to unfold. This time around, the world could become unrecognisable over the span of decades — or less.

This period of transformation could bring astonishing prosperity, with AI enabling life-saving medical breakthroughs and innovations for tackling the climate crisis. But it could also throw us unprepared into an alien world of challenges. Just imagine those hunter-gatherers suddenly finding themselves in crowded settlements where diseases spread like wildfire, while also facing warfare between organised armies for the first time. Or imagine pre-industrial humans forced to contend with enormous factories pumping out pollutants — and mysterious new weapons called ‘nuclear missiles’ that can wipe out entire cities.

This article will explain why we think advanced AI could be this transformative, and why working to address the risks — and broadly make the future of AI go well — may be your best opportunity to have a positive impact in the world.

Summary

We expect there will be substantial progress in AI in the coming decade, potentially even to the point where machines outperform humans in many, (if not all), tasks. Replacing human workers with AIs in critical fields could drastically increase innovation and economic productivity, leading to a rapid and dramatic transformation of society.

This transformation could bring enormous benefits, helping us solve currently intractable global problems. But it could also pose severe risks, some of which could be existential — meaning they could cause human extinction, or an equally permanent and severe disempowerment of humanity. For example, humanity could lose control over its future to highly intelligent AIs, or a dangerous group could use AI systems to achieve (and maintain) unprecedented power over other humans.

There aren’t nearly enough people trying to address these challenges, and existing incentives don’t necessarily favour work on the most serious risks. We estimate that there are only a few thousand people focused on tackling the most important challenges from AI — far fewer than we see working on other world problems, such as climate change, and far fewer than we think is warranted, given the scale of the changes we may be about to see.

Because of all this, we think the challenges that advanced AI poses are the most pressing problems facing humanity today.

You can find full explanations of the specific risks raised by advanced AI — and what you can do about them — in our series on the world’s most pressing problems.

Why we think advanced AI poses the world’s most pressing problems

For over a decade, we’ve looked into the biggest problems in the world and approaches to solving them. We think the cluster of challenges raised by advanced AI are the most pressing problems facing humanity today — given their scale and the promising but neglected opportunities to address them.

Our concern about AI risks isn’t a reaction to the surge of interest in AI since the 2022 release of ChatGPT. We’ve argued that AI could pose catastrophic risks since 2016, and others raised related concerns long before then (1 2, 3, 4).

In short, we think it’s plausible advanced AI could radically transform the world. This could pose extreme challenges for humanity, and it presents a potentially unique opportunity for having a positive impact.

We go through the specific challenges we think are most pressing in our problem profiles. This article explains why we think advanced AI gives rise to such important issues in general.

There are a lot of arguments you could make here — like the argument that advanced AI will constitute a “second species” or that AI will make the 21st century “the most important century” for humanity.1

But here’s the version of the argument we feel most compelled by:

- AI could replace human labour in some of the most economically valuable fields.

- Replacing human labour in these fields could trigger the next radical transformation of society.

- This transformation could be extremely rapid and dramatic, especially if there are fast feedback loops in AI R&D.

- A rapid, AI-driven transformation would raise a range of major challenges, including existential risks.

- Work on these challenges is tractable but neglected.

We’ll argue for each of these claims below.

To be clear, not all existential-scale issues with advanced AI need to route through this argument. Even without automating lots of human labour, AI systems could still cause enormous harm. For example, malicious actors could use AI to design novel bioweapons or carry out sophisticated cyberattacks. That in itself could be enough reason to work on specific AI risks.

But the story we tell below — with the world rapidly being transformed through widespread automation — is the most wide-ranging case we know of for prioritising AI risks more generally. It explains why a variety of unprecedented challenges could emerge around the same time, and why we might not have much time to prepare.

1. AI could replace human labour in the most economically valuable fields

Many technologies — like cryptocurrency, NFTs, the ‘internet of things,’ fusion, and quantum computing — have been overhyped. People often have high expectations of how much a new innovation will change the world, and reality sometimes falls short.

But we think AI is going to be different.

That’s because, unlike other technologies, AI has the potential to compete with — and even go beyond — human intelligence. And that means it could replace and reproduce the main driver of progress in our history: flexible human labour.

Some technologies, like ATMs, mimic extremely limited forms of human labour. Others, like steam engines and computers, also amplify what humans can do. But the idea behind artificial intelligence is that it’ll be able to do almost any work humans can do — and do so mostly autonomously.

ATMs didn’t make all the bank tellers unemployed2 because there were other tasks the humans could easily shift into. But imagine an ATM that could not only hand out cash, but also manage the bank’s IT systems, contribute to company strategy, and give customers tailored financial advice. Imagine it could do this mostly without our help, and more cheaply than human workers would. If that were the case, it’s not clear why the bank would keep humans employed at all.3

Now suppose the same system that did all this for the bank could also do equivalent work for tech companies, scientific research labs, consultancy firms, think tanks, The New York Times, the US government, and so on.

That’s the prospect raised by AI.

We’re already seeing glimpses of AI’s increasingly general ability to do human work. AI systems today can do things that just a decade ago would’ve been astonishing.

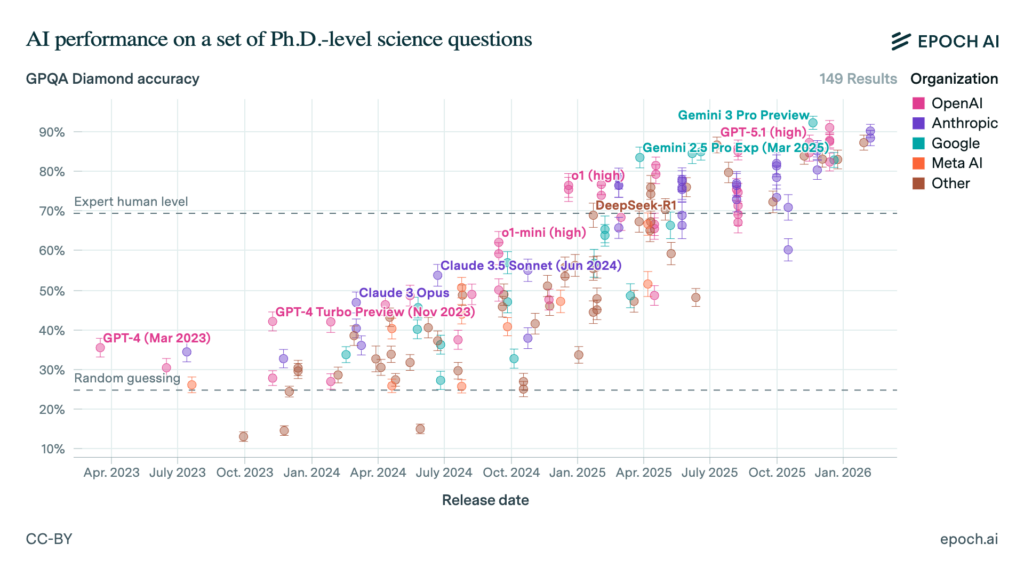

For example, consider the rapid progress language models have made on the GPQA benchmark, which asks challenging, PhD-level questions about chemistry, physics, and biology. In mid-2023, frontier AI performance was just slightly better than random guesswork on these questions. But since early 2025, many models have been outperforming human experts — and sometimes by a large margin.

They’ve also shown impressive improvement on software engineering tasks. For example, Anthropic’s agentic coding tool Claude Code enables users to build applications by describing what they want — even if they have no coding experience.

A senior engineer at Google reported that Claude Code took one hour to generate a prototype of a system her team had spent a year exploring approaches to building. And Anthropic built its ‘Cowork’ product (a more user-friendly version of Claude Code for non-developers) in under two weeks by getting Claude Code to write most of the code.4

Current AI systems can also:

- Predict complex biomolecular structures and interactions: Google DeepMind’s AlphaFold 3 — a successor to a Nobel Prize-winning AI system — can predict how proteins interact with DNA, RNA, and other structures at the molecular level.

- Solve hard maths problems competitively: Multiple AI models have reportedly achieved gold medal performance in the International Mathematical Olympiad. Separately, when 30 top mathematicians were challenged to devise problems they believed AI wouldn’t be able to solve, OpenAI’s o4 mini thwarted many of their best attempts — even solving one PhD-level question in about ten minutes.

- Improve robotics: Many leading robotics models are now AI-driven. For example, Boston Dynamics is enhancing its Atlas robots with Google DeepMind AI to help them better understand and manipulate their environments. These robots will be deployed for industrial work at Hyundai factories.

- Carry out extended tasks independently on your computer: Unlike earlier models that could only generate text, new ‘agentic’ AIs like Claude Code and OpenAI’s Codex can now use many tools on your computer, execute code, search the web, and chain together multiple steps — allowing them to complete extended, real-world tasks with far less human involvement.

- Help with AI development itself: There’s also evidence that AI systems can outperform humans in AI R&D tasks, at least when limited to a two-hour time window.

- And much more.5

There are still plenty of things AI systems can’t reliably do — especially work that takes days to complete — but the list of things these systems can’t do is diminishing, and the pace of AI progress has been impressive.

Even with the range of capabilities they have today, it seems clear that AI systems could have considerable effects on society. At the very least, automating the specific tasks that AI is already good at — for example, in software engineering, biochemistry, and robotics — will speed up some areas of scientific progress and contribute to economic growth.

But we expect that AIs will become much more widely capable than they are today, and have far more transformative effects. A common adage in the industry is “today’s AI is the worst AI you will ever use.”

In fact, many people in the field think that AI will get good enough to do essentially anything that humans can do — and more.

One milestone here would be developing artificial general intelligence (AGI). People use this term in many different ways, but we’ll use it to describe AI systems that can compete with humans on almost all cognitive tasks, or at least the most economically valuable ones — think advanced scientific research, designing new technologies and products, running businesses, consulting, and so on.6 This is the kind of system leading AI companies are actively trying to build, and they’re funnelling billions of dollars into being the first to get there.

Looking at recent trends in AI development, we think it’s surprisingly plausible (though far from guaranteed) that we’ll get this sort of AGI within the next decade.

But it probably won’t stop there. There’s no reason to think that humans represent the ceiling of mental ability — so eventually, AI could greatly exceed human performance on many (if not all) cognitive tasks. Plausibly, they could even do work that’s as far beyond human abilities as calculus is beyond chimpanzee abilities.7

It also might not take long before society makes giant advances in robotics. Although today’s robots are very rudimentary, they’re improving. And as our AIs get cognitively smarter, they’ll also get better at both controlling robotic limbs and designing them. This means AI systems might quickly become able to outperform humans on any physical task as well.

Over the next few sections, we’ll explain how the advanced AIs of the future could transform society and present serious risks.

Our argument focuses on the prospect that humanity develops AGI or something similar. This isn’t the only important milestone (see below). But we think that if AI can match human abilities at the cognitive tasks that most drive innovation and economic production, that’s likely enough to enable the rapid progress we describe in the following sections.8 And if AI becomes even more impressive than this — which we think is probable — the effects could be even more dramatic.

Could less advanced AI systems still pose existential risks?

In short: yes, we think so.

In this article, we’re focusing on AI systems that are very skilled at a wide range of tasks. That’s because we think systems like this pose the highest and most obvious chance of transforming society and throwing up many extremely serious risks.

But we don’t think this is the only milestone in AI capabilities progress worth worrying about. For example:

- Even narrowly capable AI tools could be used to cause serious harm. An AI that excels at biotechnology research could make it easier for people to develop dangerous pathogens — regardless of whether it can also trade stocks or carry out business strategies. An AI that is only useful for launching powerful cyberattacks could still shift the global balance of power. And so on.

- We might face rapid, destabilising changes to society in the lead up to developing AGI, not just after it arrives. As AI gradually automates more and more tasks, we could see increasing levels of disruption across the economy. As we’ll discuss later on, AI systems starting to automate AI R&D itself could be especially disruptive, introducing dramatic feedback loops in AI progress.

This could be enough reason to prioritise working on AI risks now, even if you don’t think we’ll get AGI any time soon.

2. Replacing this much human labour could trigger the next radical transformation of society

So what would it mean if AI systems could outperform humans on such a wide range of tasks?

The first thing people often think of here is widespread unemployment. This is a serious possibility, and would have severe consequences for society.9 But we think focusing on it is actually missing an even bigger story.

A world with machines that can replace this much human labour would look so dramatically different that it can be hard to imagine.

For some sense of comparison, think of how different the world is today to how it was for our ancestors 200 years ago, 2,000 years ago, or 20,000 years ago. The worlds before electricity, or the printing press, or agriculture literally looked quite different, and they had entirely different ways of life.

With each of these major breakthroughs in technology, the world has been transformed.

Take the first Agricultural Revolution. Before agriculture, humans were mostly hunter-gatherers and often lived in small bands.10 The development of farming technologies like ploughs allowed us to produce far more food per person, leading to the first cities. And, to an increasing extent, some people could specialise in tasks other than finding food — which allowed humans to invent metalwork, writing, and early governance systems.

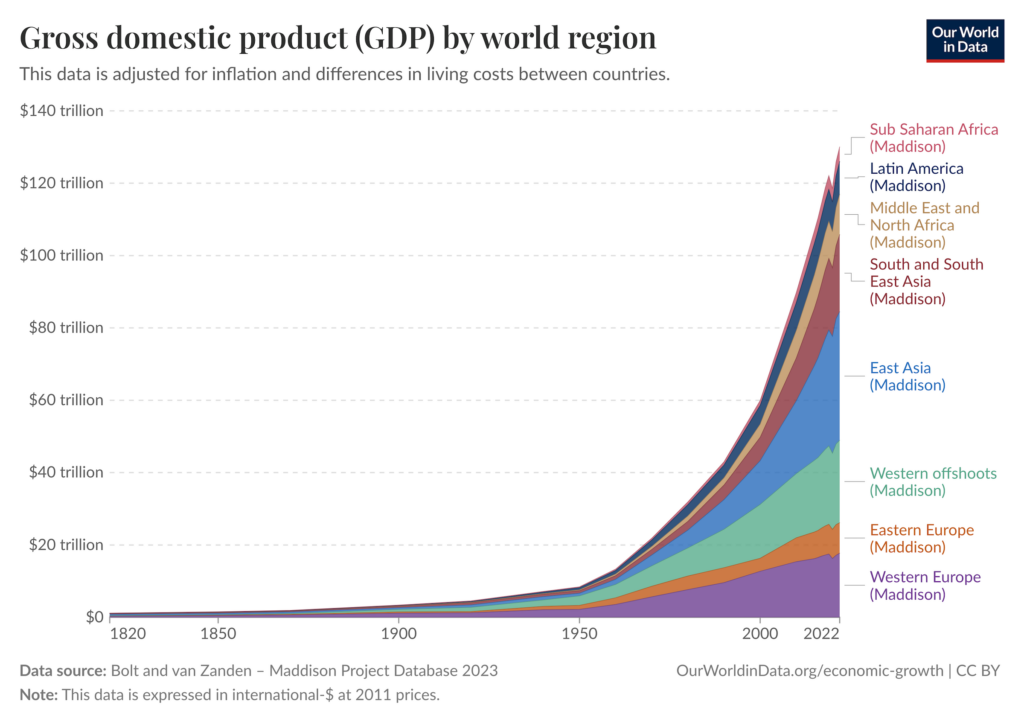

The Industrial Revolution followed a similar pattern. The arrival of technologies like the steam engine dramatically increased productivity — and sparked innovations in manufacturing and communication. Once again, this led to radical changes in how humans live: goods that were once luxury items became available to ordinary people, railways connected distant cities, and huge swathes of people shifted from rural to urban life.

What’s going on here?

Each period of transformation in history has its own complex story, and there are competing theories about what drove them. But one popular explanation says we keep seeing the same rough pattern: powerful new technology both enables us to sustain larger populations and lets people do more with the same bodies and minds. This means more human labour and greater productivity — which has compounding effects, as it leads to a wave of even further innovation.11

Since innovation often feeds economic growth, humanity has also become much wealthier in this process. In fact, since the late stages of the Industrial Revolution, we’ve seen roughly exponential growth in GDP.12

A common thread in all these stories is that it seems growth has always been reliant on human labour — society has only been able to progress as fast as humans can produce and implement new ideas (that is, new theories, inventions, ways of working, and so on).

But we’re now on the brink of a new breakthrough.

If future AIs can replace human workers in the most economically valuable fields, we’ll no longer be so reliant on human labour to sustain these cycles of compounding innovation and wealth. Instead, AI could become the primary driver of progress.

We think this could lead to another transformation of society.

Like other technological breakthroughs, it could enable society to produce far more ideas and far more economic output. But unlike previous technologies, AIs could actually take over the processes that most drive innovation and economic production (including the process of designing better AIs). And as we’ll discuss next, these ‘AI workers’ could also have huge advantages over their human counterparts.

This could mean the transformation brought about by AI is extremely rapid, and more dramatic than anything we’ve seen before.

3. This transformation could be extremely rapid and dramatic

So what could happen as AIs automate more and more of the economy?

At the very least, we expect to see the total amount of labour quickly increase — since, unlike humans, AI systems can be easily copied at scale, given enough hardware.

Let’s say we build an AI that could replace a human engineer. Estimates suggest huge uncertainty here, but running anywhere between thousands and hundreds of millions of copies of this AI at once may be feasible, depending on the circumstances.13

And this number could grow fast. With efficiency improvements to the algorithms behind these AI workers, we’ll be able to run a greater number of copies with the same amount of compute.14 We might also be able to allocate more compute to running copies, by buying more chips or designing more efficient ones. Soon, we could have an AI workforce the size of a significant fraction of the world’s working-age population.15

AI workers could also have other advantages over human workers:

- AIs can work much faster than humans, often compressing several days of information processing into minutes.

- AIs may be able to coordinate far more efficiently between themselves than humans do — perhaps at lower costs and greater scales.

- AIs can become specialised very quickly, with different versions fine-tuned to be exceptionally good at specific tasks.

Based on these advantages alone, we could soon be seeing unprecedented levels of innovation and economic production as more work is performed by AIs. This could transform society — for the same reasons automating physical labour did during the Industrial Revolution.

And we think things could be even faster and more dramatic than you might expect based on the above.

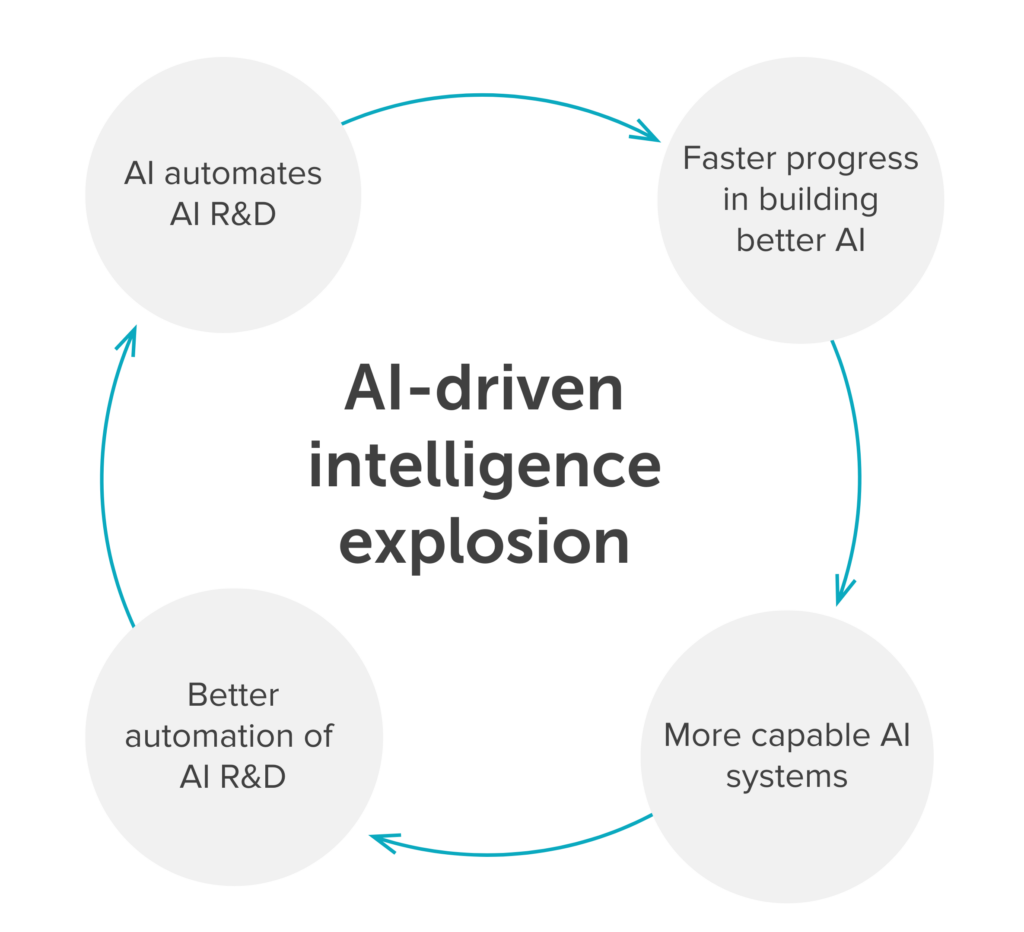

That’s because, at some point in this story, we expect AIs will be used to automate AI research and development itself. And this might trigger an “intelligence explosion”: a period of rapid technological progress driven by AI systems that can create better AI systems.

Here’s how it could unfold:

- AI systems become good enough to automate all or most work in AI R&D.

- These AI workers help us build better AI systems much faster.

- These better systems are then even more useful for automating AI R&D, which lets us build even better systems, and so on.

If this happens, it could create a positive feedback loop in which AI systems get better and better — possibly over a very short period of time.16

And this wouldn’t just mean building AI systems that are better and better at AI R&D. It would mean speeding up improvements to AI capabilities more broadly, giving us increasingly capable and general AI workers to deploy across the wider economy — which, in turn, could accelerate progress in most areas of society.

What would “accelerated progress” look like?

As we’ve said, previous periods of transformation in history were ultimately limited by the pace at which humans could produce and implement new ideas (that is, new theories and inventions and ways of working). But now imagine having a vast workforce of AIs that can produce far more brilliant ideas than us, much faster than we could before — and act on them more efficiently.

We think this could transform society over a shorter timeframe than we’ve ever seen.

What would this even look like? For one thing, scientific discoveries could be made at unprecedented speed. The market could suddenly be flooded with new technologies that would otherwise have taken decades to develop. Infrastructure and manufacturing could expand to scales we can barely imagine today. More speculatively, if AI workers are deployed more widely, we could see a surge of fresh ideas — not just in science and technology, but in art, politics, philosophy, entertainment — that fundamentally change how we even think about the world.

The world could get much richer, too, since many innovations can increase economic production. In fact, some researchers think an influx of new ideas from AI workers would lead to “explosive” economic growth — and in turn, some of this new wealth could be used to accelerate idea production even further.17

How quickly could society be transformed, exactly? There are some constraints on how “explosive” the trajectory of human progress can get, even with these feedback loops in play. For example:

- At some point, we’ll hit bottlenecks on AI development — e.g. the availability of compute, energy, or high quality data — that limit how much better AI workers can get over a short period of time.

In every field, making progress could get increasingly difficult as AI workers quickly exhaust the low-hanging fruit of discoveries and new ideas.18

But even after accounting for these effects, some researchers still argue that the effects of AI automation could compress a century worth of progress into a decade.

This level of progress couldn’t be sustained forever. But the world could already have been radically reshaped by the point things slow down — like how the Industrial Revolution eventually came to an end, but left behind a world that was totally unrecognisable.

4. A rapid, AI-driven transformation would raise a range of major challenges, including existential risks

The idea that AGI could supercharge innovation and economic output could be worth celebrating. The world could become extraordinarily rich, and we could rapidly develop new technologies that help us tackle the climate crisis or eradicate diseases.

Indeed, the promise of the technology is one reason why we expect some people to be excited about developing advanced AI systems. As Dario Amodei (CEO of Anthropic) puts it: a big motivator of AGI development is “a genuinely inspiring vision of the future”.

Generally speaking, fears of emerging technology are often unjustified. Many innovations that have been viewed with suspicion, like vaccines and railways, have ended up being hugely beneficial for humanity.

But in this case, things seem different. For the first time, we’re designing a whole new population of highly intelligent beings — agents that can do the most economically valuable things human minds can do, and might not rely on humans to do them.

This introduces complex dynamics we don’t seem prepared to deal with and don’t even fully understand. Humans navigating advanced AI could be like toddlers trying to navigate a world of adults, with changes to everything we know — in science, the economy, geopolitics, and even our ways of life — happening faster than we can get to grips with the difficult new concepts behind them.

Given the uncertainty around how AI development will unfold, it’s hard to predict exactly what challenges we’ll face. But the ones that seem most worrying to us are:

- We’ll encounter agents that could be much smarter than humans, and might have goals of their own. Those goals might lead them to undermine human interests or even disempower humanity if we can’t control them.

- Small groups could gain unprecedented power. If elite groups can control powerful AI, they’ll be far less reliant on humans to get things done. With a vast AI workforce, they could amass previously unseen levels of economic and political influence, or even seize power — and probably wouldn’t have strong incentives to represent the interests of the broader population.

- Dangerous technologies, like bioweapons, could become much more accessible. Access to highly capable AIs could make it much easier to design or get hold of dangerous weapons, significantly lowering the bar for people to cause devastating harm to humanity.

- We may create a large new population of beings whose welfare and interests matter, raising complicated questions about how to coexist with them.

- These factors may drive conflict and unrest, possibly culminating in a great power war or creating other unforeseen challenges.

How we navigate these dynamics could determine whether the future goes well or badly.

If we handle things wisely, we could create a flourishing future with unprecedented prosperity for all sentient beings, and could even spread to the stars. But if we lose control of advanced AI, or if bad actors use it to undermine the rest of the world’s interests, we could face a catastrophe — like humans permanently losing our ability to shape the future, or going extinct.

In other words, we think these issues have existential stakes, making them among the most pressing problems in the world.

And although we’re hopeful that these issues are tractable, we can’t just assume our institutions will navigate them well by default. After all, this is confusing, unprecedented territory. And we’ve seen society stumble into disaster when facing new challenges we haven’t sufficiently planned for — just think about the slow institutional responses to early COVID-19 warnings, or the numerous close calls we’ve seen with nuclear weapons.

Read more about specific AGI risks

We’ve written a series of articles explaining the AI-related issues we think pose the greatest chance of existential catastrophe, why we need people working on them, and what you can do to help.

The speed of this transition could matter a lot

There are two ways speed can matter critically to this transition:

- It matters how much time we have from now until we have extremely capable and general AI systems

- It matters how quickly the world is radically transformed by these systems once they arrive

If there’s only a few years until we get AGI or something similar, then we have limited time to avert the risks.

And if advanced AI changes the world very quickly, we might not have time to adapt to the changing circumstances and make wise decisions.

Even now, our institutions sometimes act too slowly — for example, it took around 50 years from the initial scientific warnings about global warming for the milestone Paris Climate Agreement to be signed. Unless we make big changes to how our institutions work, if AI becomes rapidly more capable and more productive, it seems it will be extremely difficult for society to keep up.

There is lively debate over how soon advanced AI systems might arrive and how quickly they might change the world. But there’s at least a decent chance that they will be here within the next decade and things will change very fast — indeed, the level of expert concern suggests we need to take this possibility seriously (1 2, 3). And given the stakes here, we think it’s important to prepare for this possibility even if there’s only a small likelihood — like a 10% chance — of it coming true.

This means we can’t just ignore the risks or delay acting on them. We need to find robust solutions before it’s too late.

5. Work on these problems is tractable but neglected

We’ve been helping people who want to work on this problem for over a decade. In this time, the field has grown substantially.

A 2025 analysis put the total number of people working on existential risks from AI at 1,100 — and we think even this might be an undercount, since it only includes organisations that explicitly brand themselves as working on ‘AI safety.’

We’d estimate that there are actually a few thousand people focusing their work on the most important risks raised by AGI. But to put that into perspective, Nature Conservancy alone has 3,000–4,000 employees, and it’s just one of many organisations working on environmental protection and climate change. Other global issues like public health also receive a lot of attention — for example, the World Health Organisation employs over 8,000 people.

This means AI risks are severely neglected in comparison to many other world problems — so each additional personal working to address them can make a bigger difference.19

We’re also optimistic that we can make progress on these problems. After all, humans are choosing to design and deploy these technologies, which means we have some influence over how things go.

Part of the challenge here is that the people who currently have the most influence over AI development aren’t necessarily incentivised to prioritise safety. AI companies want to make money and face pressures to develop technologies without fully accounting for the risks they impose on society. Political leaders care about public opinion and election cycles, which gives them less time and motivation to focus on serving broader or longer-term interests. So we need people who want to prioritise using their careers to help others to work on the major challenges that might otherwise be ignored.

There are lots of ways you can help tackle these challenges. Check out our hub of AI career resources for more.

Objections and replies

We’ve argued that automating human labour could transform the world at an unprecedented pace, but there are several ways our argument could be wrong.

- An intelligence explosion might not happen. We might deploy a generation of AI workers to automate some fields, but fail to get them to create even better or more general AI workers — perhaps because we hit the ceiling of what current AI approaches can achieve, or we fall into another “AI winter”. We’d still get a one-time increase in the size and efficiency of our workforce, making society much more productive. But we probably wouldn’t see the dramatic, compounding improvements we described earlier.

- The constraints to progress could be stronger than we’re expecting. Even if AIs do help us build increasingly capable AI workers, the feedback loop this creates might not be quite as ‘explosive’ as we’ve described. For example, bottlenecks in AI R&D — like the availability of compute, energy, and high-quality data — could mean developing the next generation of AI workers is just a slow process. And in every field we try to automate, the returns to effort could sharply diminish as AI workers quickly exhaust the low-hanging fruit, causing the effects of an intelligence explosion to fizzle out.

- Human-dependent tasks could turn out to be critical bottlenecks. Some economically valuable tasks — for example, those requiring complex interaction with the physical world, or managing projects over weeks or months — could just take an especially long time to automate. At least in the early stages of automation, the speed of AI-driven progress could be seriously constrained by the pace at which humans can do those remaining tasks.

- Our model of human progress could be missing key components. We’ve argued that increased labour and new ideas can drive rapid progress, pointing to historical examples like the Industrial Revolution. But other drivers we haven’t explicitly considered here, like institutional or cultural changes, could be crucial — and at the time we get AIs capable of replacing human workers, these drivers could just be weaker than would be necessary to support something like “a century of progress in a decade.”

In any of these scenarios, we still think AI could transform the world (and pose serious risks). But this transformation probably wouldn’t happen as rapidly as we’ve imagined. And as we argued, speed does matter: it affects how much time we have to adapt to the changing circumstances and make wise decisions.

If the above objections are correct, it might also be really hard to sustain a period of supercharged innovation and economic production. In that case, progress could fizzle out quickly — perhaps even before we see changes as dramatic as we did during the Industrial Revolution.

But given the scale of the risks here, we think it’s important to be prepared for a scenario where AI does transform the world rapidly and dramatically, even if there’s a relatively small chance (say, 10%) of this happening.

Still, the uncertainty here does make it harder to weigh up working on AI risks against other pressing problems, like factory farming.

This all sounds pretty wild. Could AI really cause outcomes as bad as human extinction?

The argument we made earlier — that the transformative effects of AI could create unprecedented challenges that threaten humanity’s survival — feels convincing to us. But it’s always worth doing a sanity check on bold and provocative arguments. One way to do that is to look at what people in the field and other leaders say about a topic. So: what do they say?

Several leading institutions are already treating frontier AI as posing catastrophic risks:

- Researchers and CEOs More than 1,000 AI scientists and industry leaders — including Geoffrey Hinton, Yoshua Bengio, Sam Altman, and Demis Hassabis — signed the Center for AI Safety’s one-sentence warning that “mitigating the risk of extinction from AI should be a global priority alongside pandemics and nuclear war.”

- National governments. At the UK government’s AI Safety Summit, 28 countries (U.S. and China included) issued the Bletchley Declaration, acknowledging “potential for serious, even catastrophic harm” from frontier models and pledging joint risk-mitigation work.

- US executive action President Biden’s 30 Oct 2023 executive order compelled US labs to share safety-test results with the government before releasing powerful systems — a measure unprecedented outside biosecurity or nuclear security. President Donald Trump’s administration has also decided to treat AI as a potential national security threat, despite appearing to be sceptical of the idea that AI could pose catastrophic risks.

Some leaders disagree:

Meta’s chief scientist Yann LeCun, for example, has called extinction worries “preposterous,” arguing that AI can be engineered to be safe.

Other influential scientists, such as Gary Marcus, Andrew Ng, and Melanie Mitchell have shared scepticism about the potentially existential risks and transformative effects of AI.

Surveys of AI researchers point to non-trivial extinction odds:

Katja Grace of AI Impacts surveyed 2,778 AI researchers on a range of key questions in the field. The median survey respondent assigned at least a 5% probability that advanced AI could result in human extinction (or a comparable disaster), and roughly one-third to one-half of participants put the risk at 10% or higher.

It’s possible researchers in their own field are exaggerating the danger — or underestimating it. Still, this level of concern should prompt us to take the risk very seriously.

Forecasters take note (but doubt the risks):

The Forecasting Research Institute conducted the Existential Risk Persuasion Tournament in 2022 to investigate disagreements on this topic.

Overall, they found that AI raised the biggest concern about existential risk from the participants of all the topics covered. But there was a big split in opinion on the risks between domain experts in AI and people with a strong track record in superforesting:

- Domain experts in AI estimated a 3% chance of AI-caused human extinction by 2100 on average, while superforecasters put it at just 0.38%.

- Both groups agreed on a high likelihood of “powerful AI” being developed by 2100 (around 90%).

- Even AI risk sceptics saw a 30% chance of catastrophic AI outcomes over a 1,000-year timeframe.

Note, though, that given the developments in AI since 2022, we’d expect both groups would now expect timelines to powerful AI to be significantly shorter. We think this would likely raise their estimates of the risks.

Overall view:

Many leaders and experts recognise the potential of AI to pose major risks, including at the level of human extinction. But unlike other problems that humanity faces, such as climate change, this isn’t a matter of scientific consensus — there’s ongoing disagreement, and many credible people think the risks are lower than we do.

Still, given the stakes, we think it would be reckless to dismiss the idea that AI could cause outcomes like human extinction. Even a relatively small chance of catastrophe is worth taking seriously.

Some people think arguments like those in this article are just a response to the current wave of AI hype and won’t stand the test of time.

It’s possible we’ve updated our beliefs too strongly on the basis of the latest AI developments, and our predictions could turn out to be wrong. But it’s worth noting that the basic ideas of this article are not especially novel or unique to our particular time period. Prominent thinkers have been warning us about the dangers and transformative potential of AI since the 1800s:

- 1863: English novelist Samuel Butler speculated in a letter that machines would eventually surpass humanity, with humans becoming the “inferior species.”

- 1920: Playwright Karel Čapek, who coined the word “robot,” wrote a play in which artificial workers rebel and eventually cause human extinction.

- 1940–1950: Issac Asimov wrote a series of stories about AI and robots, which highlighted the need to ensure their safety for humanity and suggested they’d develop the ability to steer humanity’s future.

- 1950: John von Neumann, a prolific and highly influential physicist and mathematician, reportedly said: “The ever-accelerating progress of technology and changes in the mode of human life […] gives the appearance of approaching some essential singularity in the history of the race.”

- 1951: Alan Turing, considered the father of theoretical computer science, wrote: “it seems probable that once the machine thinking method had started, it would not take long to outstrip our feeble powers… At some stage therefore we should have to expect the machines to take control…”

- 1965: Mathematician I.J. Good said: “Since the design of machines is one of these intellectual activities, an ultraintelligent machine could design even better machines; there would then unquestionably be an ‘intelligence explosion,’ and the intelligence of man would be left far behind.”

We don’t take any of these claims as strong evidence for the case that AI poses existential risks. After all, many historical figures — even extremely smart and influential scientists — have had erroneous beliefs about the future.

But they do show us that the argument that this is all “just a fad” doesn’t hold up to scrutiny.

In some senses, yes — but this doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be worried about it.

Like many other technologies, AI has had its own cycles of hype and bust. Some people think the current trajectory of high investment and fast progress could fizzle out, and even be followed by another “AI winter.”

But that’s not a good reason to ignore the risks. Although it’s likely some of the drivers of AI progress will eventually slow down, we think there’s a good chance we’ll already have AGI (or something similar) by the time this happens. And at that point, we could already be facing major challenges we’d wish we were more prepared for.

It’s also worth noting that AI doesn’t need to be fundamentally different to previous technologies to change the world and pose really serious risks. After all, other general-purpose technologies like the steam engine have done this before — the Industrial Revolution fuelled huge growth, but also precipitated climate change and laid the groundwork for the invention of nuclear weapons.

Even if AI were ‘just’ another general-purpose technology, it could be as impactful as this. And that alone would be a big deal.

But we do think there are ways in which AI might be genuinely different from anything humanity has previously seen, making it potentially more transformative and more risky than previous technologies.

For one thing, we argued in Sections 1, 2, and 3 above that AI systems could effectively take over the processes of innovation and economic production — meaning progress would no longer be reliant on human labour, and could happen much faster than ever before.

And even if you’re sceptical of that particular story, it still seems hard to deny that something unprecedented is happening here. For the first time, we’re designing a new form of intelligence that will potentially surpass ours. We could encounter a whole new population of highly capable agents with their own interests — and perhaps even the capacity for welfare and suffering. In some senses, they could be our competitors. And the dynamics this introduces could be unlike anything humanity has ever had to navigate before.

People have been saying since the 1950s that artificial intelligence smarter than humans is just around the corner.

But it hasn’t happened yet.

Some have argued that producing artificial general intelligence is fundamentally impossible. Others think it’s possible in theory, but unlikely to actually happen, especially not with current deep learning methods.

However, we think there are compelling reasons to believe AGI is achievable:

- The existence of human intelligence demonstrates that general intelligence is at least possible in principle. Human brains are made of ordinary matter following the same physical laws as computers.

- While past predictions were overly optimistic about how long it’d take, they weren’t necessarily wrong about the fundamental possibility of AGI. The field ran into blockers early on, but researchers found ways around them using creative new methods — and they now have access to vastly more computational power to run experiments and train new AIs than we could have imagined a few decades ago.

- In recent years, we’ve seen progress we don’t think would have been predicted by those who believed powerful, general AI would never be developed. For example, large language models have demonstrated emergent behaviours that weren’t explicitly programmed, like few-shot learning, analogical reasoning, and cross-domain transfer.

- Though some argue current AI methods will never grasp certain forms of intelligent reasoning, these critiques have often been proved wrong. For example, Yann LeCun claimed in 2022 that deep learning-based models like ChatGPT would never be able to tell you what would happen if you placed an object on a table and then pushed that table, because such a basic situation was never described explicitly in text — but GPT-4 can now walk you through scenarios like this with ease. In the words of AI researcher Leopold Aschenbrenner: “if there’s one lesson we’ve learned from the past decade of AI, it’s that you should never bet against deep learning.”

There’s real uncertainty here, and the sceptics might be right that there are some things advanced AI systems will just never achieve. But for AI to transform the world, the important question isn’t whether we’ll replicate every aspect of human cognition exactly. It’s whether we can create systems that can:

Match or exceed human performance across the tasks that matter most for scientific research, economic productivity, and other domains where intelligence is most valuable

Perform those tasks faster or more cheaply than human workers can

Work autonomously enough that progress in the fields they automate are no longer bottlenecked on the speed of human labour

All three of these things seem quite possible.

And even this much may not be necessary for AI to pose serious — or even existential-scale — risks. For example, our argument that people could catastrophically misuse AI mostly depends on AI systems becoming useful tools for designing weapons. An AI that’s great at assisting humans with biotechnology research could make it far easier for people to develop dangerous pathogens — regardless of how well it performs at other types of research, or how much human oversight it needs.20

So even if you think we’ll never build AIs that are fully general or completely autonomous, the risks could still be extremely serious.

There’s lively debate over when we’ll build ‘AGI’ (or other advanced AI systems capable of transforming the world in the ways we’ve described).

We think there’s a decent chance this will happen soon — perhaps within the next decade. And we’re not alone.

But it’s worth considering other possibilities. For example, researcher Ege Erdil has made an influential argument for AGI being multiple decades away. And some people think it’s even further out than that.

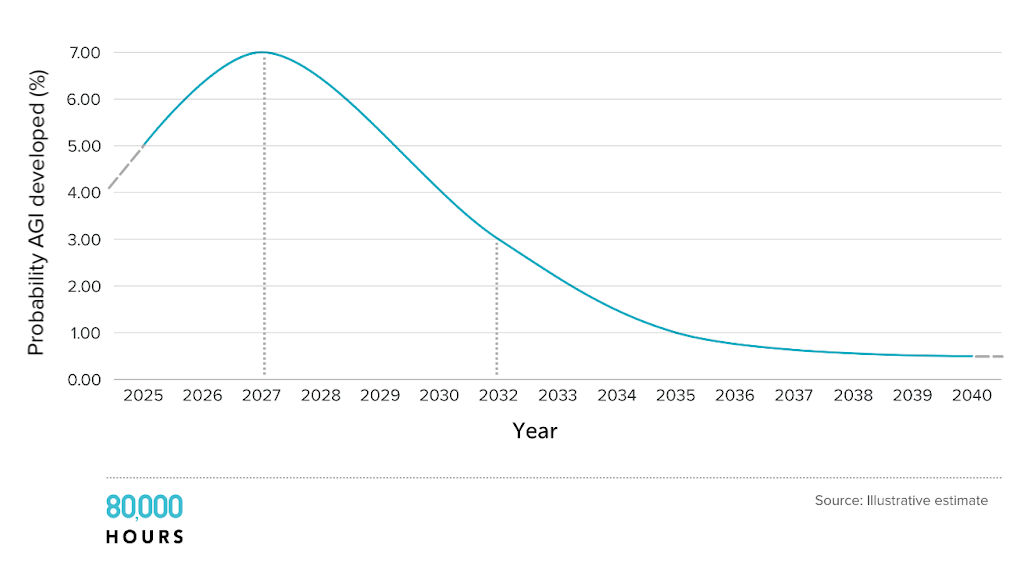

Plus, even people who think there’s a good chance that AGI (or something like it) will arrive soon tend to also think there’s a good chance that it will take a while. Their ‘probability distributions’ for when AGI will arrive are usually shaped something like this:

Even if AGI is many decades away, we think it will still transform the world when it arrives, and create unprecedented challenges. But on this longer timeframe, work to address these challenges would be less urgent, because we’d have more time to prepare.

Despite this, we still think it makes sense for many people to focus on AI risks now. That’s because:

- There’s huge uncertainty around how long it will take for AGI to be developed. We need to prepare for the chance that it happens very soon, so that we’re covered in the worst-case scenarios.

- Some issues with advanced AI might just take a long time to solve. Deep technical challenges could take many years of research to untangle, and some governance issues might require us to redesign how our institutions work — which won’t happen overnight. Putting more work in now will give us a better chance of navigating the risks competently when they start to emerge.

- Many people who could help a lot in a decade’s time should start now — especially if they are early in their career. It takes time to build up expertise and career capital, so “we still have years” isn’t a reason not to get started.

There are definitely dangers from current artificial intelligence.

For example:

- AI has frequently been linked to child safety concerns — with reports of AI chatbots generating sexualised images of children, engaging minors in sexual conversations, and in some cases, even encouraging emotionally dependent teenage users to commit suicide.

- Data used to train neural networks often contains hidden biases. This means that AI systems can learn these biases — and this can lead to racist and sexist behaviour.

- AI models are trained on copyrighted material without permission or compensation, raising serious questions about intellectual property rights and threatening the livelihoods of artists, writers, and creators.

- AI tools make it easier to run sophisticated scams at scale — like deepfake videos impersonating senior employees of companies to authorise fraudulent money transfers.

These dangers are real and serious — and lots of people should focus on addressing them. But we still think that the amount of work going towards longer-term AI risks needs to significantly increase.

The good news is that there isn’t always a big tradeoff between addressing shorter-term or longer-term AI risks. Lots of work that’s geared towards existential threats from AI systems is also relevant to solving problems with existing AI systems. For example, some AI safety research focuses on ensuring that ML models do what we want them to, and will still do this as their size and capabilities increase; other research tries to work out how and why existing models are taking the actions that they are. Both of these things would help us prevent future AI systems from taking power — but they’d probably also help us prevent current AI systems from discriminating against marginalised groups or exploiting vulnerable users.

We also think the current dangers are just the tip of the iceberg. As AI systems get more capable, the risks could get increasingly serious. As we’ve argued, future systems seem like they could pose threats not only to individual humans, but also to the very existence of humanity — say, by enabling a catastrophic pandemic that wipes out much of the population, or helping a small group establish a long-lasting authoritarian regime.

Ultimately, not all work on future risks will translate neatly into progress on today’s issues. But we have limited time in our careers, and choosing which problem to focus on could be a huge way of increasing your impact. And it seems important for many people (though not all!) to focus on addressing the worst-case possibilities. Read more on why we think it’s appropriate to prioritise between issues.

Technological optimists point out that past technologies have generally made life better, not worse. Why should AI be different?

While technology has indeed brought many benefits, it has also created new risks and challenges. Nuclear weapons gave us both nuclear power and the threat of nuclear war. Advanced biomedical science has cured many diseases, but it also raises the risk of bioweapons and disastrous leaks of dangerous pathogens. Industrial factory farming has made for cheaper meat, but it also is a moral catastrophe for the animals themselves and has many negative side effects for humans.

We agree that technology has usually benefited humanity overall, but the question is whether it will in this case.

There are enough precedents of dangerous technological developments to be cautious, and there are specific reasons in this case for concern, as we’ve discussed above. And given the potential scale and speed of AI development, the margin for error may be smaller than with previous technologies.

That something sounds like science fiction isn’t a reason in itself to dismiss it outright. There are lots of examples of things first mentioned in sci-fi that then went on to actually happen (this list of inventions in science fiction contains plenty of examples).

There are even a few such cases involving technology that are real existential threats today:

- In his 1914 novel The World Set Free, H. G. Wells predicted atomic energy fueling powerful explosives — 20 years before we realised there could in theory be nuclear fission chain reactions, and 30 years before nuclear weapons were actually produced. In the 1920s and 1930s, Nobel Prize-winning physicists Millikan, Rutherford, and Einstein all predicted that we would never be able to use nuclear power. Nuclear weapons were literal science fiction before they were reality.

- In the 1964 film Dr. Strangelove, the USSR builds a doomsday machine that would automatically trigger an extinction-level nuclear event in response to a nuclear strike, but keeps it secret. Dr Strangelove points out that keeping it secret rather reduces its deterrence effect. But we now know that in the 1980s the USSR built an extremely similar system… and kept it secret.

It’s reasonable when you hear something that sounds like science fiction to want to investigate it thoroughly before acting on it. But having investigated it, if the arguments are solid, then simply sounding like science fiction is not a reason to dismiss them.

We never know for sure what’s going to happen in the future. So, unfortunately for us, if we’re trying to have a positive impact on the world, that means we’re always having to deal with at least some degree of uncertainty.

We also think there’s an important distinction between guaranteeing that you’ve achieved some amount of good and doing the very best you can. To achieve the former, you can’t take any risks at all — and that could mean missing out on the best opportunities to do good.

When you’re dealing with uncertainty, it makes sense to roughly think about the expected value of your actions: the sum of all the good and bad potential consequences of your actions, weighted by their probability. Expected value isn’t the only framework to use — we also think it’s important to temper your estimates of expected value using common sense and other heuristics — but it’s a really useful indicator of how important a certain course of action is.

Given the stakes are so high, and the probabilities of the risks from AI aren’t that low, this makes the expected value of helping with this problem high.

We’re sympathetic to the concern that if you work on AI, you might end up doing not much at all when you might have done a tremendous amount of good working on something that’s more certain. But we think the world will be better off if we decide that some of us should work on solving these problems, so that together we have the best chance of successfully navigating the transition to a world with advanced AI rather than risking an existential crisis.

You might think it doesn’t make sense to focus on the risks from future AI systems when the world faces so many other challenges.

For example, you might want to do whatever you can to prevent the most death and suffering that’s happening now. This would probably lead you to prioritise addressing factory farming or even wild animal suffering, since these issues concern present harms and are also incredibly neglected relative to their scale.

Even if you do want to focus on making humanity’s future go well, you might feel the risks from future AI systems are just too uncertain. In that case, you’d probably choose to work on threats that feel more concrete at this stage, like catastrophic wars.

It’s certainly reasonable to prioritise working on something else over AI risks. It would be arrogant to claim we’ve figured out all the world’s problems well enough to know the most pressing ones are definitely all downstream of powerful AI.

But we still think focusing on the risks from advanced AI is often a bet worth making, because:

- As we’ve explained, there’s a material possibility future AI systems could cause humans to go extinct or permanently lose control of the future.

- And as time goes on, more and more of the theoretical reasons for concern — like the potential for deceptive behaviour in AI systems — are being borne out in practice.

- If AI does transform the world, this would probably shape all the other challenges society faces, and dictate how they can or should be addressed. For example, what happens with AI might determine the military capabilities of the world’s greatest powers, as well as the diplomatic tools they use to handle conflicts. So making sure powerful AI is handled responsibly could be a big component of addressing many other world problems.

We don’t think everyone reading this should drop what they’re doing to work on AI risks, and we’re still excited to see people make progress on other pressing problems. But if you can find a role focused on AI risks that really suits you, we think there’s a very good chance that’s the highest expected impact thing you could do.

What’s next?

Inspired to work on addressing the risks from advanced AI?

Our job board features opportunities in AI technical safety and governance:

Want one-on-one advice on pursuing this path?

If you think this path might be a great option for you, but you need help deciding or thinking about what to do next, our team might be able to help.

We can help you compare options, make connections, and possibly even help you find jobs or funding opportunities.

Learn more

- Preparing for the intelligence explosion by Will MacAskill and Fin Moorhouse

- How AI-driven feedback loops could make things very crazy, very fast by Benjamin Todd

- The Most Important Century, a series by Holden Karnofsky and other authors

- Could advanced AI drive explosive economic growth? by Tom Davidson

- AI 2027 by Daniel Kokotajlo, Scott Alexander, Thomas Larsen, Eli Lifland, and Romeo Dean (we’re sceptical that things will play out quite as quickly as in the scenario this describes — and in fact, the authors have published an updated model with more modest predictions of when AI will reach certain capabilities milestones)

- Our AI guide summary

- Will we have AGI by 2030? by Benjamin Todd

- When do experts expect AGI? by Benjamin Todd

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Cody Fenwick, who drafted an earlier version of this article (much of which was incorporated here).

Thanks also to Arden Koehler, Adam Bales, Andreas Mogensen, Benjamin Todd, Niel Bowerman, and Aaron Gertler for input.

Notes and references

- The AI Impacts website has a summary of prominent arguments that AI poses existential risks, as well as individual articles on each of these arguments.↩

- In fact, employment of tellers increased after the introduction of the ATM.

Economist James Bessen explained on the EconTalk podcast:

So, what happened when automatic tellers came in? Basically starting in the mid-1990s, ATM machines came in in big numbers. We have, now, something like 400,000-some installed in the United States. And everybody assumed — including some of the bank managers, at first–that this was going to eliminate the teller job. And it didn’t. In fact, since 2000, not only have teller jobs increased, but they’ve been growing a bit faster than the labor force as a whole. That may eventually change. But the impact of the ATM machine was not to destroy tellers, actually it was to increase it.

What happened? Well, the average bank branch in an urban area required about 21 tellers. That was cut because of the ATM machine to about 13 tellers. But that meant it was cheaper to operate a branch. Well, banks wanted, in part because of deregulation but just for deregulation but just for basic marketing reasons, wanted to increase the number of branch offices. And when it became cheaper to do so, demand for branch offices increased. And as a result, demand for bank tellers increased. And it increased enough to offset the labor-saving losses of jobs that would have otherwise occurred. So, again, it was one of these more dynamic things where the labor-saving technology actually created more jobs.

- There are some arguments suggesting we’ll still keep humans employed in this scenario. For example, Maxwell Tabarrok has argued that even if AIs become better than humans at every task, they’ll still have to specialise in the tasks they have the greatest comparative advantage at — and humans will remain employed in the areas where their own disadvantage is smallest.

We’re not sure how strong arguments like these are. As we’ll discuss later, once we have an AI that can replace a human worker, we might easily be able to run a huge number of copies of it. In that case, AI labour won’t be so scarce that we’ll have to restrict its uses to the tasks AIs are best at — we could probably afford to implement much more widespread automation.

And even if some work continues being performed by humans, the effects of automating large parts of the economy would still be significant, just as the Industrial Revolution transformed society while still leaving some work for humans.↩

- For more on what Claude Code can do, and what that might mean for the future of both AI and the software engineering world, check out this piece from SemiAnalysis arguing that Claude Code is an “inflection point” for AI agents.↩

- This is just a selection of examples we find especially compelling, but there’s plenty more that AI systems can do.

Sora and Veo can produce impressive videos based on text prompts.

Frontier models are becoming increasingly ‘multi-modal,’ combining the abilities to process text, images, and spoken languages.

There’s evidence that AI systems can outperform doctors in diagnosing patients and detecting cancer.

Models like GPT-4 have been found to significantly improve the productivity of lawyers.

Studies suggest that some AI systems can anticipate results in neuroscience better than human experts, and assist with drug discovery.

We’re seeing impressive demonstrations of AI-based cybersecurity.

AI self-driving cars are becoming more popular, with Waymo now conducting 450,000 rides per week in the US as of December 2025.

In tests run by the US Air Force, AI systems generate valid military strategies up to 90% faster than traditional methods would.↩

- While this characterisation of ‘AGI’ reflects how some leading AI companies talk about their ambitions, it’s slightly narrower than other popular definitions. For example, many people use ‘AGI’ to refer to fully general systems, which can do literally every cognitive task a human can do.

What matters for this article is not whether we get these fully general systems, but that advanced AI will exhibit the specific abilities we think are likely to be challenging for humanity. So we’ve tried to highlight a range of tasks we think it could be particularly consequential to automate.

As our co-founder Ben Todd says in a footnote to “The case for AGI by 2030“:

Usually it’s better to try to forecast specific abilities rather than ‘AGI’. Otherwise, people focus on different definitions of AGI depending on what they think could cause transformative impacts on society. For instance, people who think an acceleration of AI R&D is what matters may focus on a definition they believe is sufficient for that threshold; while someone who thinks what matters is a broad economic acceleration will be more concerned by the ability to do real jobs and robotics.

Bear in mind comparatively narrow systems (e.g. specialised in scientific or AI research) might still be able to cause transformative impacts, so ‘AGI’ might not even be necessary for dramatic social change.

On the other hand, if AIs remain limited to cognitive tasks, they won’t be able to automate the entire chain of production, limiting some of the most dramatic possible outcomes.

- This is already happening to some extent. AI systems have many inherent advantages over humans, like their ability to process huge amounts of information in minutes, which means they can do things humans simply can’t. For example, AlphaFold can predict the structures of proteins based on an input list of molecules — something human minds are fundamentally unable to do. As our AI systems get more and more sophisticated, they might unlock new abilities that humans can barely even imagine.↩

- Some people think progress this rapid won’t be possible unless we also automate the physical tasks involved in innovation and production — or else progress will get bottlenecked on the pace that humans can do manual work.

We think this is an open question. But our instinct is that AI systems that can’t do any physical tasks themselves, but have sufficiently advanced cognitive abilities, could still indirectly speed up many important physical tasks. For example, they could design much more efficient production processes, or push more humans to take up jobs requiring physical labour as AIs fill the ones that don’t.

In any case, as we said earlier, we think rapid cognitive improvements in AI could lead to rapid improvements in robotics. So even if there’s a serious bottleneck here, it might not hold progress back for long.↩

- Fortunately, there are already promising ideas for solving this problem — such as the introduction of universal basic income and democratising ownership of AI capital.↩

- Some anthropologists think there was a lot of variation in social structure during this period of history — that is, while some groups were small and egalitarian, others were larger and more hierarchical. (For more, see this article by Manvir Singh.)

Still, it seems clear that the Agricultural Revolution reshaped human ways of life.↩

- This ‘population-ideas’ account of the history of human progress has been popular since it was put forward by Michael Kremer in the 1990s, but is sometimes disputed.

We think it’s possible that this account is over-simplified or incomplete. For example, some economists have emphasised the role of other important factors — like institutional development and culture — in shaping human progress.

But even if the ‘population-ideas’ account doesn’t capture the whole story behind the Agricultural or Industrial Revolution, it still seems likely that new technologies played at least some important role in these periods of accelerated human progress — and could do so again in future.↩

- For most of human history, GDP per capita has been roughly flat. The approximately exponential trend shown in the graph here is a very recent phenomenon that we started seeing in the early 1800s. And even since then, growth hasn’t been perfectly exponential — it has varied considerably year on year, with periods of acceleration (like the post-WWII boom) and slowdowns (e.g. during major recessions). But when we zoom out to look at economic growth over centuries, we see that these fluctuations don’t disrupt the overall trend.↩

- This is an enormous range. We’ve seen lots of different estimates in different contexts, and there’s a lot of uncertainty:

- The authors of AI 2027 predict that when we get the first unreliable AI coding agent, we might just deploy a few thousand copies — but when we get ‘Agent-3,’ the first superhuman AI coding agent, we’ll deploy hundreds of thousands of copies of it.

In Machines of loving grace, Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei suggests we’ll be able to run “millions of instances” of a powerful AI system with the materials used to train it.

Epoch estimated in October 2025 that companies like OpenAI theoretically have enough hardware today to deploy around seven million “digital workers” to perform the tasks AIs are currently good at — but the authors acknowledge their uncertainty, giving a huge 90% confidence interval of 400,000 to 300 million.

Tom Davidson has argued that once we train a system that could fully replace a human AI engineer, we might run 100 million copies of it.

The variation here is partly because we’re imagining AI workers at different levels of proficiency in each context — and the incentives to run lots of copies of them will depend on how good they are. If they’re fairly unreliable, like the “stumbling agents” described in AI 2027, it won’t make sense to deploy hundreds of millions of them. But as they get more reliable and more generally capable, companies will have an appetite for running many more.

There’s also serious uncertainty over how many copies we’ll be able to deploy. That’s because we don’t know how much compute will be needed to run each future AI worker effectively. And the more run-time compute they each require, the fewer copies we can run with the resources available at the time.

But even if we can only run a comparatively modest number of AI workers at first, that could still lead to a big increase in the overall productivity of our economy. As we explain next, we might be able to rapidly scale up this AI workforce — and each of these AI workers could be significantly more productive than their human counterparts.

We recommend AI 2027 for a detailed walkthrough of how we might quickly end up with a vast and very capable AI workforce, even if we start off by just deploying a few thousand AI workers. (Although we are sceptical that AI will develop transformative capabilities as fast as the authors of AI 2027 suggest, we think their analysis is well worth reading.)↩

- We’re already seeing fast efficiency improvements to AI systems — as time passes, we can do far more with the same amount of compute.

In 2024, researchers at Epoch found that:

the level of compute needed to achieve a given level of performance has halved roughly every 8 months, with a 95% confidence interval of 5 to 14 months.

And if we see an ‘intelligence explosion’ (as we describe later), these efficiency improvements might happen even faster than before — which could enable the AI workforce to expand shockingly quickly.↩

- If we’re automating physical labour as well as cognitive labour, scaling the workforce up will also require making progress in robotics. But once we have the algorithms and hardware we need to automate many physical tasks, some researchers have argued that it won’t take long to produce a large fleet of robots to do them — see, for example, this article by Ben Todd, which argues that we could scale to a billion robots within five years.

This seems especially likely if we get what Forethought calls an “industrial explosion.”

The idea of rapidly scaling up robot workers is also a key part of the “race” scenario laid out in AI 2027.↩

- Some researchers distinguish between multiple types of feedback loop in which AI systems help us build better and better AIs. For example, Forethought’s article on “Three Types of Intelligence Explosion” highlights the following types:

- A software feedback loop, where AI develops better software. Software includes AI training algorithms, post-training enhancements, ways to leverage runtime compute (like o3), synthetic data, and any other non-compute improvements.

- A chip technology feedback loop, where AI designs better computer chips. Chip technology includes all the cognitive research and design work done by NVIDIA, TSMC, ASML, and other semiconductor companies.

- A chip production feedback loop, where AI and robots build more computer chips.

These types of intelligence explosion all follow the same rough structure we’ve described in the text. And we think all three could happen and contribute to the development of better AI systems — though they will probably do so to different extents and at different speeds.

See Forethought’s article for a much more detailed analysis here.↩

- It’s not clear whether this surge of new ideas would actually translate into such rapid economic growth (as measured in GDP). Some researchers point to Baumol’s cost disease as a reason to expect this wouldn’t happen.

We’re not economists, so we can’t say definitively what to expect in this instance. But it does seem possible that we could sustain a period of accelerated human progress even without explosive economic growth. For example, in a footnote to “Preparing for the intelligence explosion,” Forethought argues that we can experience major “physical growth” (i.e. in manufactured goods, buildings, and infrastructure) even if economic growth is much more modest. They provide an example of the US agricultural sector:

For instance, because the demand for agricultural products was fairly price inelastic, huge productivity gains in agriculture caused the sector to shrink from employing most the US labour force in 1900, to producing less than one percent of US GDP. Yet, we could see major physical growth independent of these effects.

For more analysis of how AI automation would affect economic growth, including the effects of Baumol’s cost disease, see “Artificial intelligence and economic growth” by Aghion et al.↩

- An influential paper, “Are ideas getting harder to find?,” has made the broader argument here in detail.

Long-run growth in many models is the product of two terms: the effective number of researchers and their research productivity. We present evidence from various industries, products, and firms showing that research effort is rising substantially while research productivity is declining sharply. A good example is Moore’s Law. The number of researchers required today to achieve the famous doubling of computer chip density is more than 18 times larger than the number required in the early 1970s. More generally, everywhere we look we find that ideas, and the exponential growth they imply, are getting harder to find.

- There are other extremely serious problems that are even more neglected than AI risks, in absolute terms — factory farming seems like an example. But neglectedness is just one factor in determining how pressing we think a problem is, overall. The potential scale of the risks from AI is a big part of why we’ve ranked them as more pressing, all things considered, than issues like factory farming.↩

- In fact, it seems we already have AI systems that could aid the development of bioweapons. In July 2025, OpenAI warned that its ‘ChatGPT Agent’ feature might “meaningfully help a novice to create severe biological harm.” These risks could heighten as frontier models become more advanced.↩