Why you should focus more on talent gaps, not funding gaps

Update April 2019: We think that our use of the term ‘talent gaps’ in this post (and elsewhere) has caused some confusion. We’ve written a post clarifying what we meant by the term and addressing some misconceptions that our use of it may have caused. Most importantly, we now think it’s much more useful to talk about specific skills and abilities that are important constraints on particular problems rather than talking about ‘talent constraints’ in general terms. This page may be misleading if it’s not read in conjunction with our clarifications.

Update Aug 2021: See this update on how the balance of funding and people has changed the last five years.

Many members of the effective altruism community see making a difference primarily in terms of moving money to fill funding gaps rather than moving talent to fill talent gaps. This seems to me to be one of the community’s more serious mistakes, which causes us to:

- Put too much weight on earning to give and fundraising.

- Put too little weight on gaining expertise and developing the skills needed for direct work.

- Overlook pressing causes that aren’t funding constrained.

In the rest of the post, I’ll:

- Outline what I mean by talent gaps.

- Suggest why the community might be biased towards focusing on funding gaps.

- Argue there are whole cause areas we’ve completely overlooked due to this focus.

- Argue that many of the causes the community does support are also more talent constrained than funding constrained.

- Argue that the importance of talent constraints compared to funding constraints is likely to increase over the next 2-5 years.

- Argue further that this imbalance is likely to persist in the long-term.

- Consider some of the arguments against focusing on talent gaps.

- Give ideas for what the community should do differently in order to focus more on talent gaps. In particular, I’ll outline who should earn to give and who shouldn’t, and list the greatest talent needs within the community.

Important caveat: I’m addressing this post towards people who already think they can do substantially more good than cash-transfers to the world’s poorest people (e.g. via GiveDirectly). This intervention has huge room for more funding, so if you think that’s the best thing that can be done, then funding is the main problem.

Table of Contents

- 1 What are “talent gaps”?

- 2 Why has the community mainly focused on funding gaps in the past?

- 3 The community overlooks causes and approaches that are talent constrained but not funding constrained

- 4 The causes the community currently thinks are most pressing are already more talent constrained than funding constrained

- 5 The balance seems likely to shift more towards talent constraints in the next 2-5 years

- 6 There are reasons to expect the balance to remain tilted in favour of talent constraint in the long-run

- 7 Considering the counter-arguments: why should the community not focus on talent gaps?

- 8 What should the community do differently?

- 8.1 Less earning to give

- 8.2 Less investment at the margin in fundraising projects

- 8.3 More people exploring direct work in new causes and approaches, and sharing what they learn with the rest of the community

- 8.4 More people getting the skills for direct work at effective altruist organisations

- 8.5 More people doing direct work in the top causes

- 8.6 Better mechanisms for coordinating people and solving talent gaps

- 9 Conclusion

What are “talent gaps”?

For some causes, additional money can buy substantial progress. In others, the key bottleneck is finding people with a specific skill set. This second set of causes are more “talent constrained” than “funding constrained”; we say they have a “talent gap”.

Many causes are both funding constrained and talent constrained. Some are mainly funding constrained; some are mainly talent constrained; and some are intractable – meaning it would be hard to make progress even with additional money and talent. These distinctions are widely accepted by people who prioritise between and within causes. (Examples will follow later in the post.)

Here’s a slightly more precise definition of talent constraint (though I’d welcome more work on it):

A cause is constrained by a type of talent, X, if adding a (paid) worker with talent X to the cause would create much more progress than adding funding equal to that person’s salary.

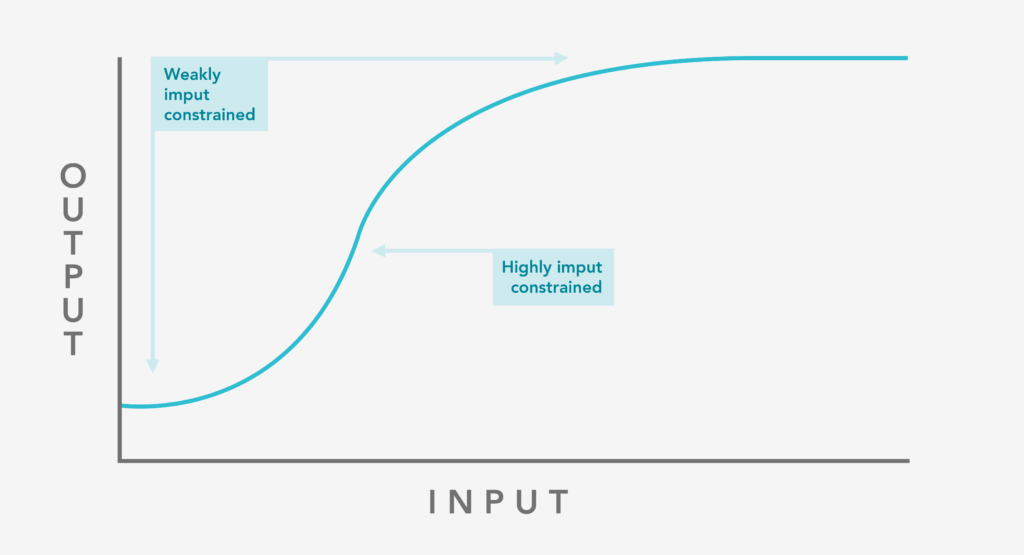

(For economists, you could think of it in terms of elasticities – a cause is talent constrained when the elasticity of output with talent X is much higher than the elasticity of output with funding required to pay for that talent at market rates).

Note there’s always some conversion rate between money and talent. It’s just that in talent constrained causes it’s relatively hard and slow to make progress with money – maybe you’d have to pay unusually high salaries, or wait a long time for new people to be trained up in the right skills.

You can gauge the relative degree of funding and talent constraint by asking leaders in the cause how they’d trade additional funding against potential hires.

(If you’re unsure that talent gaps can exist despite the option of raising salaries, see here for a more detailed model. Another way of seeing it is to note that labour and capital aren’t perfect substitutes (and labour comes in many types), so you can have differently shaped production functions with respect to each input).

Why has the community mainly focused on funding gaps in the past?

Effective altruism got off the ground with people trying to answer “how I can I spend money to do the most good?” That question is the focus of the most successful effective altruist organisation, GiveWell, and many other organisations in the movement are focused on giving money (Giving What We Can, Charity Science, Raising for Effective Giving). Earning to give (taking a higher earning career and donating the extra money to high-impact charities) is the most distinctive career path in the community.

Since many current members of the community became involved through these routes, they tend to think of effective altruism in terms of how they can donate more and donate more effectively.

Some even say “the most pressing problems in the world mainly require extra funding to solve”. But we don’t have much evidence for this – so far the community has primarily looked for funding gaps, and so funding gaps are what have been found. (To be clear, I’m not saying this applies to everyone. For example, people who got involved through the Centre for Applied Rationality usually don’t have this mindset.)

As I’ll argue in the next sections, this focus is causing us to overlook causes that aren’t funding constrained, and fail to realise that many of the causes we already support are more talent constrained than funding constrained. This in turn leads the community to put too much emphasis on fundraising and earning to give, which could mean the community will have significantly less impact than it could.

The community overlooks causes and approaches that are talent constrained but not funding constrained

Imagine that, rather than focusing on donations to charity, the founders of effective altruism had instead asked “what’s the highest impact job for a talented young person to do?” Does it seem likely that we would have come up with the same list of causes and approaches? It doesn’t seem obvious to me.

Here are some areas that seem (i) important (ii) not heavily funding constrained (iii) largely unexplored or under-appreciated by the community. I’m not saying these are high-impact opportunities, just that they seem promising and the community hasn’t done much research into them, so they could plausibly turn out to be much better than what we’re already working on.

- Foreign policy. It’s hard to buy better American-Chinese relations as a philanthropist, but it seems like an extremely important area to get right over the next century. A young person could build expertise in this area and contribute by working in the foreign service, raising the overall ability of people working in the area (even after taking replaceability into account).

- Climate policy and energy. Open Phil undertook an overview of this cause and concluded it’s not highly funding constrained, but in conversation Holden told me he thinks it’s still an important area for talented people to go into; indeed, the large pools of funding available might create greater opportunities for talent.

- Any cause that’s best served through for-profit work. For-profit activities don’t look heavily funding constrained compared to charities because they generate revenue. But some for-profits have a huge positive impact, for example by undertaking important innovation (e.g. Google) or creating consumer surplus, especially if the for-profit is aimed towards the global poor (e.g. Wave). An altruistic young person could gain the skills needed to succeed as an entrepreneur or manager, and create more for-profits that do good.

Scientific research. Scientific research is one of the main drivers of progress, but often doesn’t seem highly funding constrained, because talented young researchers can usually already get academic positions, and have much more impact than the effect of adding funding equal to their salaries. Of course, additional funding would lead to more research, because many researchers can’t secure academic positions due to lack of funding. But many of the best researchers can, and the best researchers are much more productive than the median researcher, so the cause is more talent constrained than funding constrained.

Any cause that’s best furthered by improving government operation. It doesn’t seem like giving money to the government is a top use of philanthropic money. But a talented person could go and help the government run better, increasing the impact of its existing budget, and potentially having a big impact. A quick look at the area shows that civil servants often oversee budgets of tens of millions of dollars a year, so a small increase in their ability and social motivation could have a lot of impact.

More broadly, talent constrained causes are usually those that particularly need: (i) an unusual skill set (ii) innovation and (iii) leadership (especially those where fundable organisations don’t already exist). These are all hard for outsiders to buy with money, but a talented person may be able to get themselves into a position where they can make this kind of contribution.

The causes the community currently thinks are most pressing are already more talent constrained than funding constrained

Even if we ignore the areas the community has overlooked, it still seems like most of the causes the effective altruism community supports are more talent constrained than funding constrained. For example (in all of the following, I’ve already taken account of replaceability):

- International development. If someone could set up another charity that meets GiveWell’s criteria, they would recommend it, giving the charity access to tens of millions of dollars in funding. They’ve also said that logistical bottlenecks on the ground are usually more pressing than funding. This is because there are many other large donors (such as governments and major foundations such as Gates and CIFF) who will provide funding for people who can competently scale up a proven intervention. To this end, GiveWell recently published a list of charities they’d like to see. To be clear, cash-transfers still have huge room for more funding, so international development is also funding constrained, it’s just that certain talent constraints seem similarly or even more pressing.

Building the effective altruism community and priorities research. Talented leaders in the community with a good plan can usually get funding. The majority of ‘meta’ organisations say they struggle more with hiring than fundraising (though there are some exceptions), and would often be willing to turn down major funding to secure an extra person who’s a good fit. (For more on the relative degree of funding vs. talent constraint, see Sӧren Mindermann’s series on the Effective Altruism Forum).

AI safety research. FHI and CSER recently raised large academic grants to fund safety research, and may not be able to fill all their positions with talented researchers. Elon Musk recently donated $10m through the Future of Life Institute, and Open Phil donated a further $1m, which was their assessment of how much was needed to fund the remaining high-quality proposals. I’m aware of other major funders, including billionaires, who would like to fund safety researchers, but don’t think there’s enough talent in the pool. The problem is that it takes many years to gain the relevant skill set and few people are interested in the research, so even raising salaries won’t help significantly. Other funders are concerned that the research isn’t actually tractable, so the main priority is having someone demonstrate that progress can be made. Previous efforts to demonstrate progress have yielded large increases in funding.

Promoting migration for humanitarian reasons. There are very few organisations one can fund in this field, so it’s hard for a donor to buy progress. However, if you could set up a credible organisation, it seems likely that you would find funding (e.g. Open Phil is actively looking for giving opportunities in this area).

Biomedical research. While making our biomedical research career review, we asked four professors of biomedical research how much annual funding they would trade for an “especially good researcher.” The lowest gave a figure of around £100,000, and two named figures in the millions. This suggests the cause is more talent constrained than funding constrained, though there are many complications to the argument.

The main exception to this – a cause supported by the community that seems more funding constrained than talent constrained – is ending factory farming. Jon Bockman of Animal Charity Evaluators, told me that vegan advocacy charities have lots of enthusiastic volunteers but not enough funds to hire them, meaning that funding is the greater bottleneck (unless you have the potential to be a leader and innovator in the movement). So, the more weight you put on this cause, the more funding constrained you’ll see the community. But the situation could reverse if you think developing meat substitutes is the best approach, because that could be pursued by for-profit companies or within academia.

Many leaders in the community also think the community has a greater need for talent than funding. For instance consider Holden from GiveWell in 2013 (from his conference call on altruistic career choice):

When I think whether there needs to be more money, more money is good and I think more money is definitely very helpful because money’s powerful and money can do a lot of things but at this particular moment, it doesn’t feel that’s the greatest need. It feels… and maybe that’s a temporary thing, but it feels GiveWell is a little bit money heavy and knowledge poor in a sense and may remain that way because I’m optimistic about our ability to move money and a lot of the bottleneck has to do more with finding people who know what they’re talking about, finding people who can figure out how to do things, finding people who know how to get certain things done because it can’t all be bought linearly.

Those are some thoughts. I don’t mean to be down on making money because I do think money is very important and very powerful but what I am trying to say is that when I think about what the effective altruist movement needs, I would love to see just more diversity and more people scattering into all kinds of areas and becoming really good at things that aren’t already kind of core competencies of the effective altruist community.

The balance seems likely to shift more towards talent constraints in the next 2-5 years

The earning to give pipeline

By my estimates the amount given by the earning to give community is going to rise about 10-fold in the next couple of years. This is because there are many people pursuing earning to give with very high earnings potential, but who have only just started their careers and so are not yet donating much.

Open Philanthropy

Open Phil may eventually donate as much as $8bn to whichever causes do the most good. Currently they’re only making grants of several tens of millions per year, but the plan seems to be to increase this to hundreds of millions per year in the next couple of years. They’ll need to spend well over $400m per year to deplete the $8bn pot. (A 5% return on capital on $8bn is $400m per year, then $8bn divided over 40 years is a further $200m per year). Holden confirmed in a recent blog post, “I believe that the relatively low amounts of giving we’ve recommended so far are deceptive, and I expect these amounts to rise sharply in the next year or two.”

Lots of other effort going into fundraising for effective altruist charities

Many organisations within the community are also fundraising for effective altruist charities: Giving What We Can (almost half a billion of pledged donations raised), The Life You Can Save, Raising for Effective Giving and Charity Science. These organisations are still in the early stages, and raising a rapidly growing amount of money.

No corresponding expansion in direct work

The current community is set to gain the two large extra sources of funding mentioned above without any shift in its membership. However, I’m not aware of a similarly powerful force that is going to rapidly drive up the potential for the existing community to do direct work. The best I can think of is that direct workers will keep getting more experienced, thus become better able to effectively use large amounts of funding. However, it seems doubtful we’ll see 10-fold growth here in the next few years.

For the balance not to shift towards greater talent constraints, the community will need to disproportionately absorb new direct workers compared to funders over the next couple of years. This might start to happen as outsiders see that a lot of money is available, but it takes time to involve new people in the community, make sure they have the relevant skills and come to trust them enough to fund them. It also takes time to build organisational capacity.

There are reasons to expect the balance to remain tilted in favour of talent constraint in the long-run

This section is more speculative and can be skipped, but I want to put the ideas out there so more work can be done on them.

1. The organisations in the community have a good track record of attracting money from outside the community

Many organisations in the community have attracted large donors from outside the community, such as Good Ventures (GiveWell), Peter Thiel (MIRI and Leverage), and Luke Ding (CEA).

The community, however, remains absolutely tiny compared to the total size of US philanthropy, government welfare, science funding, international aid spending, and so on – all of these run into hundreds of billions per year. This suggests there’s a huge pool of additional funds that could theoretically be drawn on by the existing community. (And from my experience, it seems easier to draw on these funds than for effective altruist organisations to hire lots of people who don’t have an effective altruist mindset).

It seems possible we could get even better at doing this, and end up with a community where a significant majority of the most talented people do direct work – either funded by a handful of large philanthropists, or working in government, academia, for-profits and existing nonprofits.

2. Effective altruism attracts people with the highest earning potential

So far, effective altruism seems to have disproportionately appealed to those with the highest earning potential, particularly people in finance and tech with quantitative skills.

If this continues, there are going to be plenty of new high potential donors coming into the community, and we’ll remain skewed towards being talent-constrained.

3. Funding gaps seem easier to resolve

Money is fungible, so once a funding gap is identified, it’s relatively easy to fill. Finding and building trusted teams of people, however, is difficult and takes a long time, and that means we need to get started immediately. (See some of GiveWell’s reflections on why building trusted teams is difficult).

A related but more speculative idea is that because funding is fungible, the top funders can more easily take the best opportunities, making the charitable market more efficient with respect to funding than to talent. This means you can have more impact by focusing on talent gaps rather than funding gaps.

I’ve also added a new, but especially uncertain argument, for why to expect talent gaps in the long-run to the footnotes.1

Considering the counter-arguments: why should the community not focus on talent gaps?

Talent gaps by definition only apply to a certain skill set, so only a fraction of people can take each talent gap. However, if you identify a funding gap, anyone can fill it because money is fungible. This means research into the highest-return uses of money is more broadly applicable. It also means it’s easier to build a community behind funding gaps, because everyone can support the same opportunities. Working on talent gaps is more complex because everyone should be doing something different. These reasons suggest that the community should first focus on funding gaps, then move to talent gaps later. I agree with this assessment, but I think now is the time to start focusing more on talent gaps.

Non-fungibility of talent also means it seems harder to develop strong, widely-recognisable evidence that you’re solving a talent gap. With funding for scalable interventions, you can often add a certain amount of funding, then evaluate the outcome, ideally through a randomised controlled trial. If you find a positive result, then you can be reasonably confident that if you add even more money, you’ll get even more positive results. With talent gaps, however, the opportunities are less standardised, so it’s harder to measure the “talent in, results out” relationship. This means that if you’re especially committed to strong evidence of impact, then that may be reason to focus on funding gaps rather than talent gaps. (Though I haven’t thought about this as much as I’d like so I could easily see myself changing my mind.)

A final benefit of funding gaps is that they’re easier to support with a fraction of your resources. If you’re 30% altruistic, you can donate 30% of your income to a high-impact cause. In most cases it’s harder to devote 30% of your working time to a cause – either you work in the cause or you don’t. This also means that it’s easier to get lots of people united behind funding gaps than talent gaps. I think this is true and the effective altruism community should continue to promote cost-effective giving, but at the margin more of the most enthusiastic people should start focusing on talent gaps.

I expect there are more downsides that I haven’t considered. I think there’s much more work to be done comparing funding gaps to talent gaps.

What should the community do differently?

In short, less earning to give and more direct work within causes (including advocacy, research and entrepreneurship).

Less earning to give

Focusing on funding gaps to the exclusion of talent gaps makes earning to give seem like a better option than it in fact is, which means there’s a danger too many people are pursuing it.

For instance, a recent post on the Effective Altruism Forum argued the long-run proportion of people pursuing earning to give should be 50-80%. The main pillar of the argument was that AMF only requires a couple of people to run, but can absorb millions of dollars of funding. Based on estimates of how much each person earning to give can donate, the post argued that there should be as many as four people earning to give per person pursuing direct work.

However, AMF has been selected by GiveWell precisely because it’s very funding constrained and not very talent constrained. GiveWell wants to identify the causes that are best for donors to support, and that means looking for causes where money is the main bottleneck. If you only consider these types of opportunities, then earning to give is going to be best for most people.

Instead of AMF, however, you could select an organisation that’s highly talent constrained but not funding constrained (like GiveWell itself or the Future of Humanity Institute), and draw the opposite conclusion: because these organisations don’t need much extra money, most people should do direct work and not earn to give.

As I’ve argued above, I think that today there are more talent constrained causes than funding constrained ones, and the balance is shifting more towards talent constraints. As a result, I suspect too many people are aiming to earn to give.

Who, on balance, should earn to give? I see this as a difficult question that’s still very uncertain. Here are some quick thoughts on when earning to give seems most promising (though I’d like to write a more in-depth post later). All of these reasons are important individually, and if several apply simultaneously, then the case for earning to give looks strong.

- You especially want to pursue a career that has little direct impact, but still want to do good. e.g. you love architecture and really want a job in the area, but don’t think you’ll have much direct impact in architecture.

You’re a really good fit for a very high earning option, like tech entrepreneurship or quant trading.

You’re extremely uncertain about which causes to support, and so you want to save money and decide where to donate it later.

You want to build career capital, and decide that working in business is the best way to do so.

You’re only prepared to devote a proportion of your resources to helping the world, and that proportion is less than would be required to get expertise in a talent gap.

You’re a major advocate for earning to give, e.g. there has been press coverage about you pursuing it.

You’re already part way down the path and it’s going well.

Less investment at the margin in fundraising projects

Many organisations in the community mainly focus on fundraising for effective charities, so also don’t contribute to solving talent gaps. They’re essentially like a higher leverage form of earning to give.

Several years ago we already had Giving What We Can and The Life You Can Save, which promote GiveWell recommended charities by encouraging people to pledge income. Then we added Animal Charity Evaluators, which researches and promotes animal charities. Then we added Raising for Effective Giving and Charity Science, which also fundraise for effective altruist and GiveWell charities, in part through encouraging people to pledge a percentage of their income. This is a lot of effort going into very similar projects, all focused on solving funding gaps.

To be clear, these are all great projects that do a lot of good. My claim is that that at the margin, I’d like to see more new projects focused on solving talent gaps, rather than fundraising.

There’s some signs this is happening, with Charity Science recently announcing they’re interested in trying to start a new GiveWell-recommended nonprofit.

More people exploring direct work in new causes and approaches, and sharing what they learn with the rest of the community

Picture the community in twenty years time. If we keep focusing on funding gaps, then we’ll end up with a community full of people with the skills that fetch the largest market value – software, finance, marketing and so on.

Alternatively, we could have a community where most people aim to become experts and leaders in a wide range of pressing causes, using this expertise to direct large pools of funding, share knowledge, and coordinate to solve big problems. My intuition is that this would be a much higher impact path.

For instance, Open Phil has said they’d like to fund a science policy reform think tank. If there were already community members with better knowledge of policy and research, and others with the right leadership abilities, this could get started next week. And this isn’t the only opportunity of this type I’m aware of. If we accumulate a narrow range of marketable skills, then a lot more opportunities like this are going to pass us by.

We’ve also seen that the community is neglecting or even ignoring huge areas that seem to have the potential for significant positive impact but aren’t heavily funding constrained. Based on the list of neglected causes above, Holden’s thoughts, and my own reflections, here are some areas about which it would be especially useful for the community to learn more:

- US politics, in particular think tanks, advocacy groups and lobbying.

- Foreign policy and geopolitics.

- China, especially in relation to foreign policy and how to get things done on the ground.

- Science and innovation funding.

- The US military, since it’s one of the main groups that will respond to catastrophic risks, and we know very little about it.

- For-profit startups focused on serving the global poor.

- Areas of academia with few effective altruists, such as the social sciences, history and biology (and many other areas seem under-represented, even the natural sciences and economics).

Based on this, some concrete paths to consider include:

- Doing a PhD. Economics is a solid option – although it’s not the most neglected, it’s still neglected relative to its importance, and has a lot of other advantages.

- Working at a think tank.

- Working in the civil service in policy-focused or foreign relations roles.

- Founding or working for tech startups focused on emerging markets.

More people getting the skills for direct work at effective altruist organisations

Tyler Alterman and Roxanne Heston recently asked 15 leaders of effective altruist organisations which talent needs are most pressing at their own organisations. Sӧren Mindermann is doing a more in-depth interview series on the same topic (see MIRI, 80k and EAF). Here’s my impression of some of themes that were mentioned more than once:

(For all of these, add “with an effective altruist mindset”, which is crucial for having the right cultural fit, motivation and knowledge.)

- People with in-depth knowledge of the policy world.

- AI Safety researchers.

- “Executive” style people who can manage a team, manage a project, and generally get stuff done.

- Operations people able to manage finance and admin.

- Researchers, especially generalists able to do global priorities and cost-effectiveness research.

- People with knowledge of media, branding, PR, market research and community building.

- People good at outreach, especially those able to come across as genuine and knowledgeable.

The survey also asked which skills they think the community will be constrained by in the near future. This also uncovered:

- People with experience of scaling an organisation very rapidly.

- Entrepreneur style people able to launch new projects.

- (And people to explore the neglected causes and approaches above).

More people doing direct work in the top causes

Based on talking to leaders in each cause, here’s my impression of the most pressing talent bottlenecks:

International development

- People with on-the-ground logistical skills in international development (i.e. the kind of person who could get 100,000 malaria nets distributed in Africa).

- Nonprofit entrepreneurs who could found one of these charities.

- Development economists and cost-effectiveness researchers.

US Policy

- Policy/advocacy experts in general, especially those who could work on Open Phil’s favoured policy causes, and science policy and infrastructure.

- People who work in think tanks, advocacy groups, and lobbying groups.

- People in party politics.

Global catastrophic risks

- Scientists with an understanding of bioengineering.

- Policy experts in relevant areas.

- People with knowledge of the US military.

- Academic climate scientists to work on geoengineering research.

- AI risk researchers.

- Managers and operations staff for AI safety research institutes.

Ending factory farming

- Animal-product alternatives researchers and entrepreneurs.

- Leaders and advocates in the animal welfare movement.

Better mechanisms for coordinating people and solving talent gaps

Talent gaps are complex to resolve, so the final area is better infrastructure to make the above happen. (This is one reason why I’m especially excited by 80,000 Hours – I think we could play a major role in doing this). Here are some simple ideas for progress:

- More people sharing their experiences in different causes and areas on the effective altruism forum, allowing the community to learn about new areas (see some questions to answer about your own career).

- More research into which causes are most talent constrained, and how these constraints can be resolved.

- Better mechanisms for connecting people in the community, such as the new EA newsletter, EA Global and career coaching.

- An effective altruism community that’s more enthusiastic about people pursuing unusual projects that aren’t either earning-to-give or working for an effective altruist organisation.

Conclusion

I’ve argued that by focusing mainly on funding gaps, the community is overlooking a wide range of causes and approaches to doing good. Moreover, even among the causes the community is focused on, most of these causes are more talent constrained than funding constrained, and this imbalance is likely to get worse over the next 2-5 years, and may persist indefinitely. In response, more people should move from earning to give into direct work, research and advocacy, and we should improve the community’s ability to tackle talent gaps.

In the early days of effective altruism, we mainly focused on funding gaps, and that made a lot of sense. If we want to maximise our impact, however, then today it’s time for stage two: effective altruism that’s highly focused on talent gaps. This is going to require a number of changes to our mindset and what we do, and I’m very excited to see how it turns out.

If you’d like to take action on the issues raised in this piece, let us know and we’ll see if we can help.

Notes and references

- Why might talent gaps to be more prevalent than funding gaps? One reason is that principal-agent problems are widespread: if you pay someone to work for you, but they don’t share your values and are doing work that’s hard to monitor, then it’s very hard to ensure they’ll act in your best interest. You can try to write contracts and add oversight to avoid the misalignment, but this just imposes further costs.

For instance, imagine trying to pay ordinary computer scientists, who don’t care about existential risks, to research the risks of artificial intelligence. It’s really hard to tell what constitutes good research progress day-to-day; the questions you’d like researched will be poorly defined and up-for-debate; and the researchers may find it hard to even guess which avenues you’ll find most important. In practice these barriers mean that only people who care deeply about the subject are worth hiring, even if they’re talented researchers.

Principal-agent problems are also part of why it’s so hard for governments to make sure non-altruistic companies act in the public interest, or ensure bureaucrats aren’t corrupt and do what’s best for society. (Perhaps this is why there are opportunities to do good by working in public service and for-profits but not by funding them, as mentioned earlier).

Widespread principal-agent problems mean that (as a donor), you can very roughly divide people into the following two types (more realistically a spectrum, but let’s keep it simple):

- People who share your values who you can trust: few principal-agent problems.

- Everyone else: many principal-agent problems.

If you want to make progress on an important social cause, you’ll want to fund people who share your values and who you can trust. After you run out of them, you’ll be left with people whose values and trustworthiness are in doubt. At this point, you’ll either have to (i) stop funding difficult to monitor tasks like research, increasing coordination, advocacy and management in novel areas, or (ii) pay much, much more to keep incentives aligned. Either way, it probably becomes harder to buy progress with money: in other words, you become talent-constrained.

This could create a world which is, in a sense, generally talent constrained. If there’s a relatively small pool of people who share your values that you can trust, and they’re already doing something pretty valuable, then at the margin, it will be far more exciting to find another trusted, skilled person who shares your values than to find the salary necessary to hire them.

There are exceptions. When simple interventions are available, like cash-transfers and malaria nets, you can monitor progress so principal-agent problems aren’t as severe and funding is the main bottleneck. At this point, you could conclude these interventions are the best we can do, and only focus on promoting them. If, however, you want to do even more good, then principal-agent problems will become crucial, and the world will be more talent constrained than funding constrained.↩