What the literature says about the earnings of entrepreneurs

This piece is part of our series on high impact entrepreneurship. Sign up to our newsletter and we’ll email you with the rest of the series.

Summary

- Until recently, academics lumped ‘entrepreneurs’ together with all the ‘self-employed’. A new paper, however, split the self-employed into those who owned incorporated businesses and those who don’t. (Though note that the incorporated self-employed are still very different from startup founders.)

- Self-employed people who own incorporated businesses earn about 50% more than people with regular jobs.

- Most of this is due to them being more educated and working harder. However, even if you correct for these factors, it seems like shifting into owning an incorporated business boosts income by about 18%.

- The unincorporated self-employed (mostly running things like hairdressers, restaurants, corner shops etc.) earn less than salaried workers on average.

- Once you try to compare like-for-like workers, you find that when people switch into unincorporated self-employment, 50% earn less than they would as a salaried worker (but gain more freedom), and 30% earn more. The overall average is about the same.

Introduction

It’s widely believed that entrepreneurs earn more than salaried workers. However, until recently the research did not seem to back this up. In fact, the findings of several studies in 1989 presented a puzzle: entrepreneurs appeared to earn less than their salaried counterparts.

In his 2013 book The Founder’s Dilemmas,1 Noam Wasserman (an Associate Professor at Harvard Business School) set it out starkly:

One recent study supports the notion that….many founders of high-technology startups believe they stand a much greater chance of becoming wealthy by launching a startup than by ordinary employment. If many founders really do believe this, it appears they are largely wrong.

For the self-employed, initial earnings are lower and earning growth significantly slower than for those engaged in paid employment. …All told, entrepreneurs earned 35% less over a 10-year period than they could have in a “paid job”.

And of course, founding a company is far more risky than earning a salary. This suggests that entrepreneurs are in most cases giving up security and making no extra money in return.

The book concludes:

The authors of these studies therefore wondered why so many intelligent people would wish to play this game if there is indeed no “private-equity premium”.

Right after The Founder’s Dilemmma was published this puzzle was solved by a paper which subdivided the self-employed into different groups.

Incorporated vs unincorporated earnings

A 2013 study by Levine and Rubinstein2 considered two groups of self-employed people: those who have incorporated businesses and those whose businesses are unincorporated. Freelancers and small business owners often remain unincorporated. However companies with high growth potential will almost always incorporate: an incorporated business exists as a separate legal entity, limiting the legal liability of the owner. (Though note that many of the incorporated self-employed are still not true startups.)

This distinction helps to divide true entrepreneurs from the rest of the self-employed, and the comparison is revealing. The study found that self-employed people who incorporated earned much more – one estimate finding that on average they earned 36% more per hour than their salaried counterparts (when matched on age, gender and education). They also worked longer hours, resulting in an even larger annual salary difference.

In contrast, the average unincorporated self-employed person earns 16.5% less than their salaried counterparts. And perhaps this is not surprising. Those who choose not to incorporate are probably not aiming to earn huge sums of money: they are most likely motivated by the freedom of self-employment.

The traits of each group

The paper also shows that incorporated self-employed people have different traits from both unincorporated and salaried workers.

The average incorporated self-employed person is highly able – they did well on aptitude tests like the SAT, they have high self-esteem, and were successful in salaried employment, earning more than other workers with similar characteristics.

They are also more likely to be rule-breakers i.e. have a minor run with the law as a teenager. Interestingly another very recent paper found that rule-breaking as a youth was correlated with higher income across the board.

In fact, the people who most exemplify these traits – what the authors call “smart and illicit” – tend to get the biggest earnings boost from switching to self-employment.3

The unincorporated self-employed, however, on average scored lower on aptitude tests than the other groups and earned low pay as salaried employees.

Moreover, the incorporated self-employed are more likely to call themselves entrepreneurs, have a patent, and report doing more work involving intellectually demanding tasks.

The overall picture is one of three groups:

- Incorporated self-employed: able risk takers, who were successful in salaried employment but switched to self-employment to earn substantially more than otherwise.

- The salaried: 90% of people in work.

- Unincorporated self-employed: seek self-employment as an alternative to poorly paid salaried work, or prefer to trade off greater autonomy for a lower salary.

A more recent study also showed that the self-employed are very different from entrepreneurs.4

Solving the puzzle

This does a lot to resolve the puzzle set out earlier. The incorporated and unincorporated self-employed are actually two very different groups. The incorporated earn more than salaried workers, while the unincorporated earn less. Since there are several times as many unincorporated workers as incorporated, when you average together the two groups, you find that the self-employed earn less than salaried workers.

Money vs power

The group of incorporated self-employed can be subdivided again, further helping to solve the puzzle. In The Founder’s Dilemma, Wasserman distinguishes founders who make ‘control-oriented decisions’ (decisions that preserve their influence over the business e.g. not taking outside investment, not bringing on a cofounder) from those who make ‘wealth-oriented decisions’ (decisions aimed at growing the business at the expense of control).

Founders focused on wealth earned on average twice as much as those who focussed on control. The control-motivated founders make up a substantial portion of startups, which brings down the overall average earnings because they prefer to trade money for greater freedom.

Putting this result together with Levine and Rubinstein’s paper, it appears that the incorporated self-employed who are also wealth-oriented will earn double as much again.

Will you earn more if you become an entrepreneur?

We’ve seen that the incorporated self-employed earn more on average, especially if they’re wealth-oriented. But the question that’s probably on your mind is: if I found an incorporated business, will I earn more? It could just be that more successful people tend to found businesses to capitalise on their success, and being self-employed is incidental to their greater earnings. If that’s true, becoming self-employed won’t boost your earnings.

Whether this is the case is a difficult question to answer, but the study also sheds some light on the question. The authors looked at salaried workers who switched into incorporated self-employment, and compared their later earnings with workers who earned the same but didn’t switch. They also controlled for a wide variety of factors, including personality, intelligence and education.

This analysis revealed a smaller but still substantial increase in average hourly earnings of 18%. And because the self-employed also work longer hours, average annual earnings increase 29%. This suggests that becoming self-employed with an incorporated business boosts your earnings. Though bear in mind that because it’s difficult to control for all the relevant factors, you need to be cautious about the findings of these types of studies.

The distribution of earnings

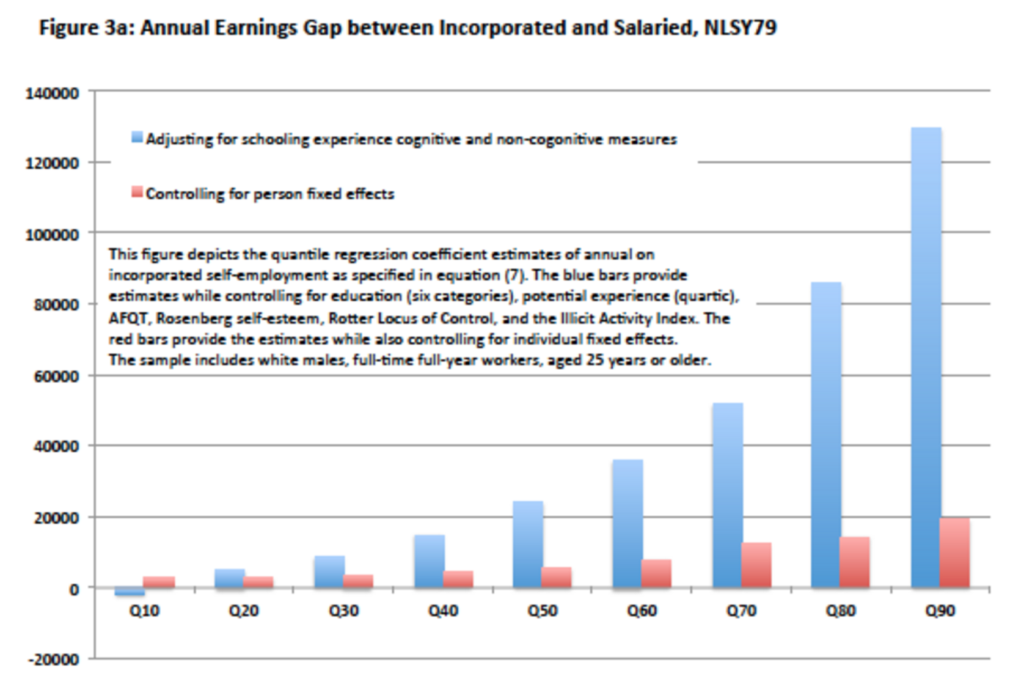

The differences are starker for the most successful self-employed. The 10% most successful incorporated workers earn about $130,000 more per year than similar salaried workers.

However, most of this boost turns out to be because these workers were already more successful to begin with. When we compare the same people over time and make all the controls mentioned above, the difference is only $20,000.

This analysis also reveals a surprising pattern – all of the incorporated workers earned more, even at the bottom 10%. I was expecting to see lower earnings at the bottom end of the distribution reflecting the greater risk of entrepreneurship. I’d like to see more studies with similar findings before putting much weight on this result.

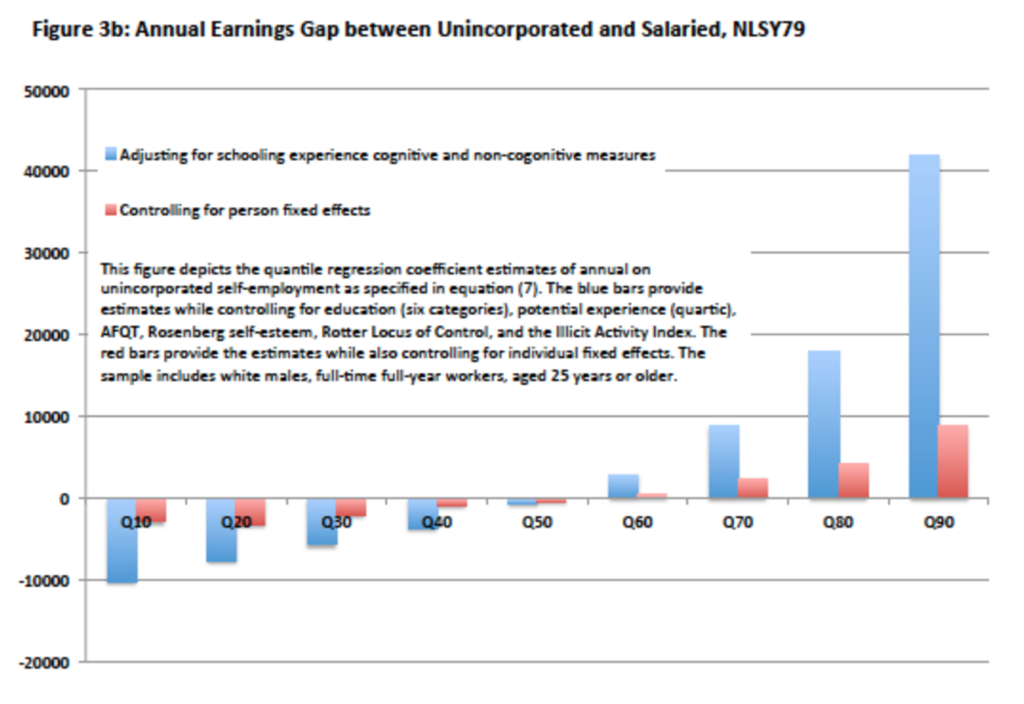

The situation for the unincorporated is different:

The bottom half earned less, while only the top 30% or so earned significantly more.

In another twist, it turns out the mean earnings of the unincorporated are several percent higher once we add these extra controls. So the main reason why the unincorporated earn less on average is because they’re less successful to begin with. Once you account for that, switching to self-employment slightly raises your expected earnings, while increasing the risk of earning less.

Should you do it?

This study is evidence that if your aim is to make more money, switching from salaried work to running an incorporated business is typically rewarded with a significant boost in earnings.

We also saw earlier that those who have the combination of “smart and illicit” traits tended to do better when they made the switch, so especially consider it if you’re in that group. There’s also money in ceding control of the company in a way that allows it to grow as quickly as possible.

The chance of earning less than you would have is also small, so the risk is low (though this result is suspicious and contrary to conventional wisdom).

Finally, the authors say in a footnote:

We find that when somebody returns to salaried work after incorporated self-employment, he returns to a wage rate that is very similar (in real terms) to the salary he had before becoming self-employed.

So the cost of trying seems to be limited to missing out on several years of salary growth.

So, if it doesn’t work out, you can probably go back.

This piece is part of our series on high impact entrepreneurship.

Sign up to our newsletter and we’ll email you with the rest of the series:

Notes and references

- Noam Wasserman (2012), “The Founder’s Dilemmas: Anticipating and Avoiding the Pitfalls That Can Sink a Startup” (Princeton University Press).↩

- Levine, Ross and Rubinstein, Yona (2015), “Smart and Illicit: Who Becomes an Entrepreneur and do they Earn More?” (Archived by archive.org: https://web.archive.org/web/20160222033032/http://faculty.haas.berkeley.edu/ross_levine/Papers/smart_and_illicit_24sep2015.pdf)↩

- Though note that these traits don’t seem to explain the difference in earnings, because the traits did not cause them to earn more while still salaried.↩

- Henrekson, Magnus, and Tino Sanandaji. “Small business activity does not measure entrepreneurship.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111.5 (2014): 1760-1765.

http://www.pnas.org/content/111/5/1760.full?sid=d6ffdb16-b18d-4190-88a9-52b7b94c1847

“The rate of billionaire entrepreneurs correlates negatively with self-employment, small business ownership, and startup rates. Countries with higher income, higher trust, lower taxes, more venture capital investment, and lower regulatory burdens have higher entrepreneurship rates but less self-employment.”↩